Spatiotemporal Assessment of Urban Heat Vulnerability and Linkage Between Pollution and Heat Islands: A Case Study of Toulouse, France

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Model Framework

2.2. Calculation of Indices and Parameters

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Environmental Mortalities

3.1.1. Data Analysis

3.1.2. Interpolated Mapping Visualization

3.2. Spatial Indicators

3.2.1. Spectral Indices/Vegetation and Land Cover Indices

- a.

- Normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI)

- b.

- Normalized difference water index (NDWI)

- c.

- Normalized difference Built-up index (NDBI)

- d.

- Land use/land cover (LULC)

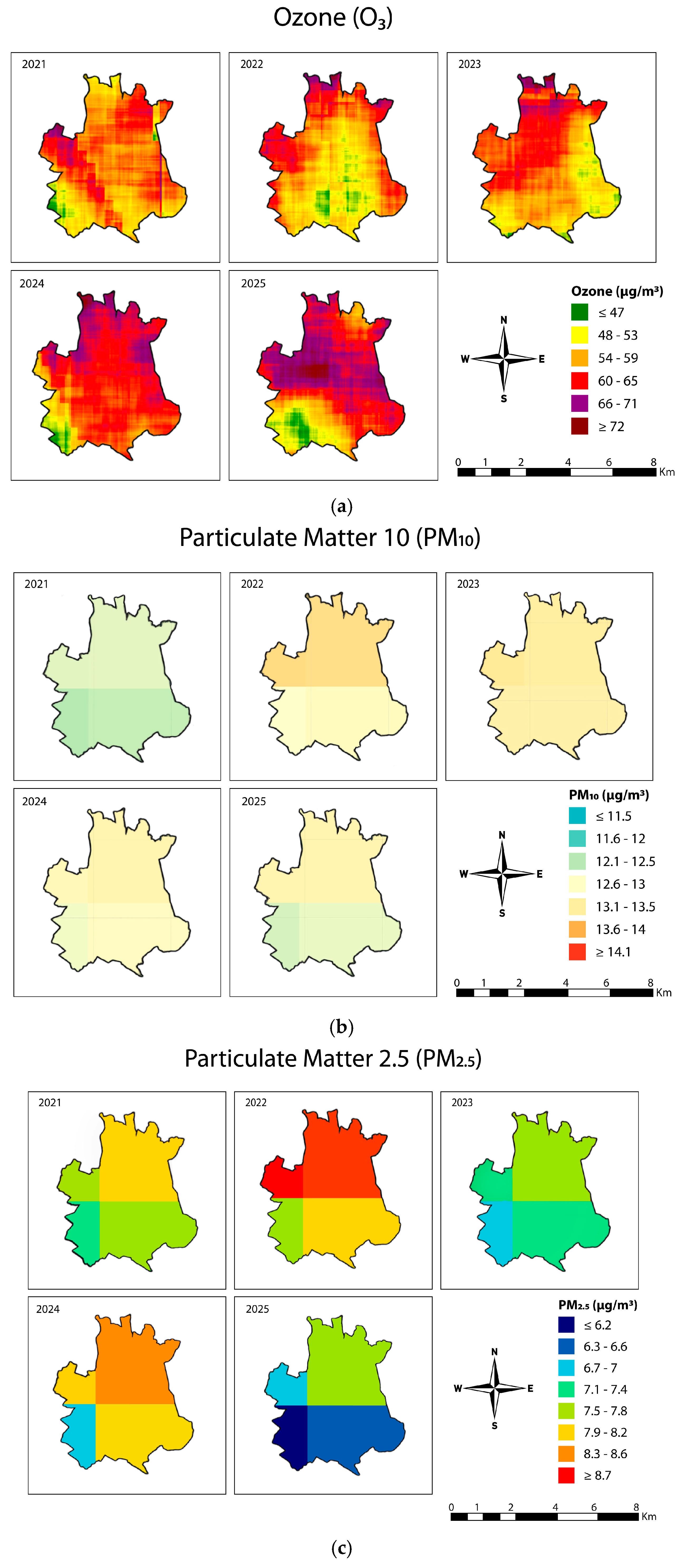

3.2.2. Air Quality

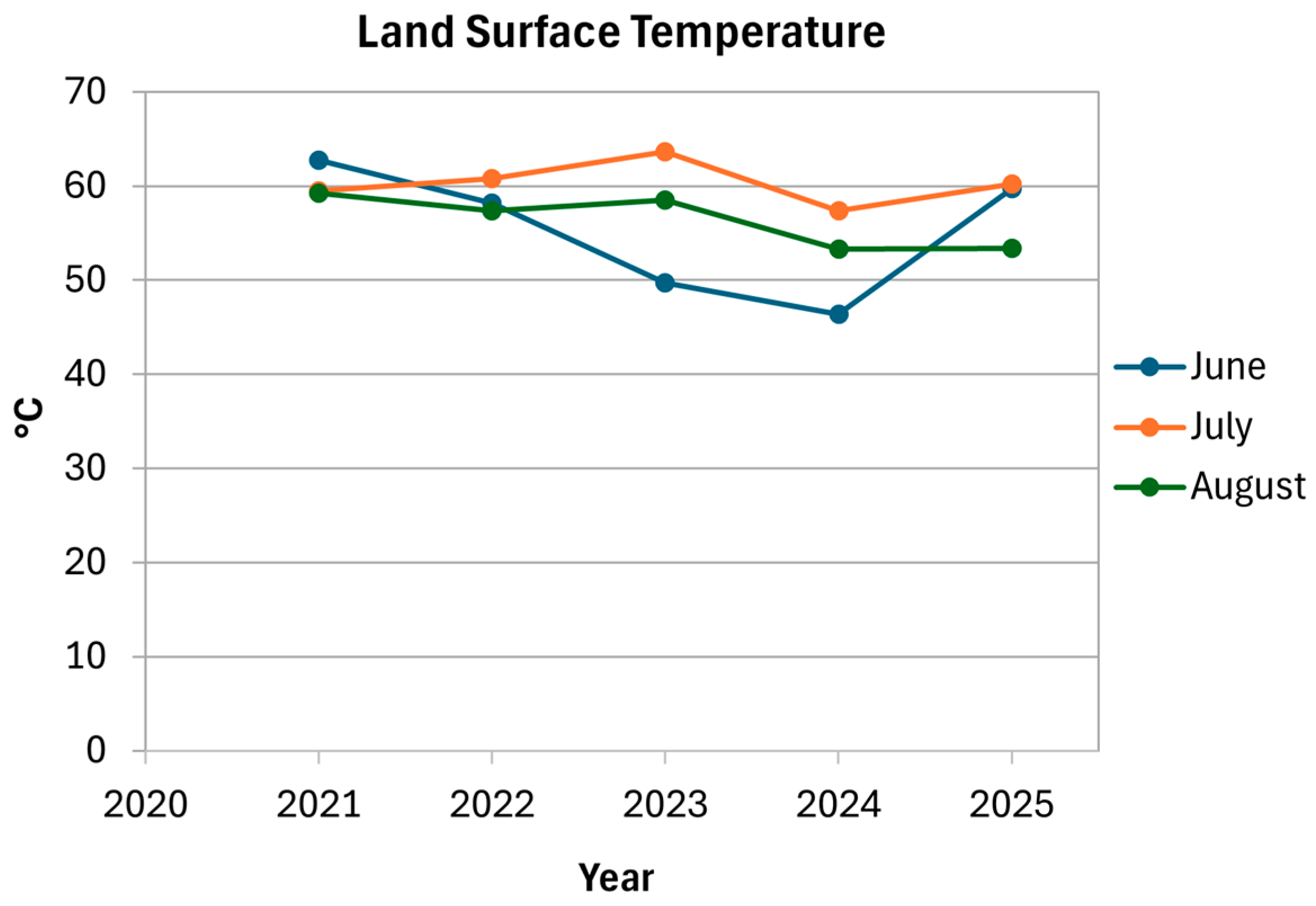

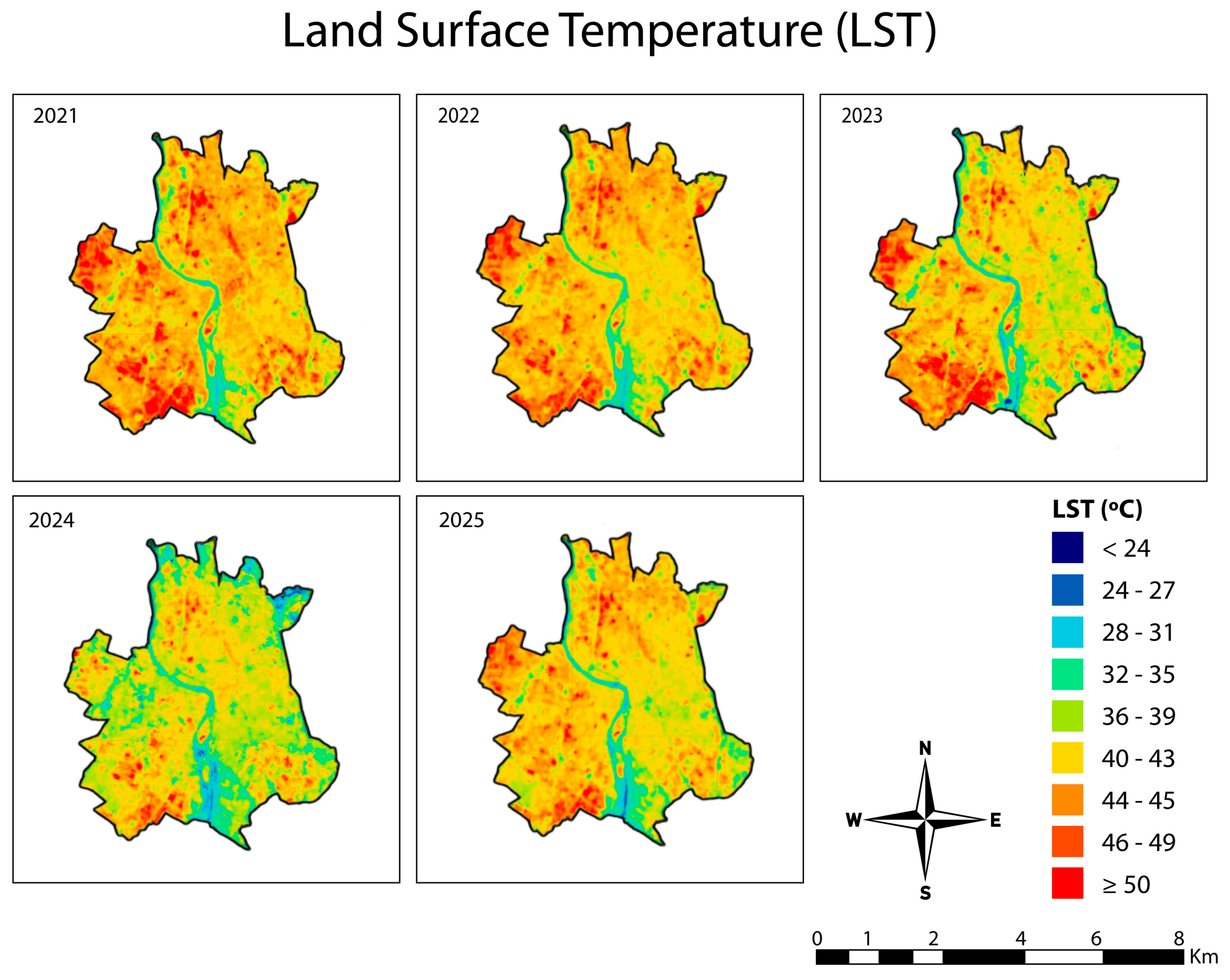

3.2.3. Land Surface Temperature

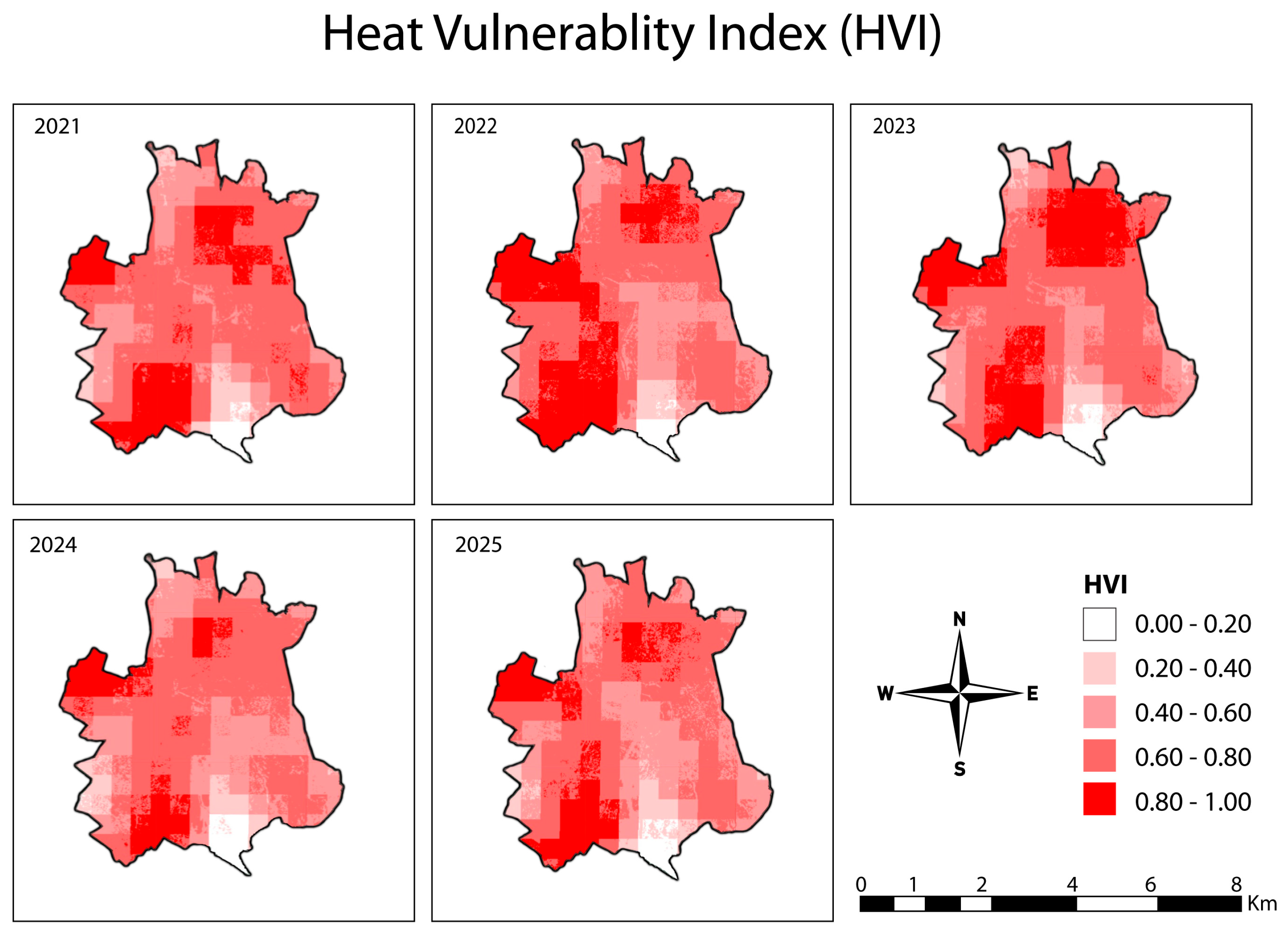

3.2.4. Heat Vulnerability Index (HVI)

3.3. Spatio-Temporal Variability Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UHI | Urban heat island |

| UPI | Urban pollution island |

| HVI | Heat vulnerability index |

| O3 | Ozone |

| LST | Land surface temperature |

| PM2.5 | Particulate matter diameter size 2.5 µm |

| PM10 | Particulate matter diameter size 10 µm |

| Surface emissivity | |

| Radiative constant | |

| Wavelength | |

| LULC | Land use/land cover |

| NDVI | Normalized difference vegetation index |

| NDBI | Normalized difference built-up index |

| NDWI | Normalized difference water index |

| AOI | Area of interest |

| NIR | Near-infrared |

| SWIR | Shortwave infrared |

References

- Matsumoto, T.; Bohorquez, M.L. Building systemic climate resilience in cities. In OECD Regional Development Papers; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lemonsu, A.; Viguie, V.; Daniel, M.; Masson, V. Vulnerability to heat waves: Impact of urban expansion scenarios on urban heat island and heat stress in Paris (France). Urban Clim. 2015, 14, 586–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evidence from French Cities. Available online: https://www.insee.fr/en/statistiques/8261528 (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Song, X.; Shi, H.; Jin, L.; Pang, S.; Zeng, S. The Impact of the Urban Heat Island Effect on Ground-Level Ozone Pollution in the Sichuan Basin, China. Atmosphere 2024, 16, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piracha, A.; Chaudhary, M.T. Urban air pollution, urban heat island and human health: A review of the literature. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Lim, J.; Skidmore, M. The impacts of heat and air pollution on mortality in the United States. Weather Clim. Soc. 2024, 16, 275–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javan, K.; Darestani, M. Assessing environmental sustainability of a vital crop in a critical region: Investigating climate change impacts on agriculture using the SWAT model and HWA method. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandentorren, S.; Suzan, F.; Medina, S.; Pascal, M.; Maulpoix, A.; Cohen, J.C.; Ledrans, M. Mortality in 13 French cities during the August 2003 heat wave. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 1518–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extreme Weather Watch. Available online: https://www.extremeweatherwatch.com/cities/toulouse/average-temperature-by-year (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Climate Adapt. Available online: https://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu/en/mission/external-content/pdfs/mission-stories-toulouse_v8_final.pdf/ (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Nayak, S.G.; Shrestha, S.; Kinney, P.L.; Ross, Z.; Sheridan, S.C.; Pantea, C.I.; Hsu, W.H.; Muscatiello, N.; Hwang, S.A. Development of a heat vulnerability index for New York State. Public Health 2018, 161, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodilis, C.; Yenneti, K.; Hawken, S. Heat Vulnerability Index for Sydney. City Futures Research Centre, UNSW Sydney. Dataset. 2018. Available online: https://cityfutures.ada.unsw.edu.au/cityviz/heat-vulnerability-index-sydney/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- City of Philadelphia. Available online: https://www.phila.gov/2019-07-16-heat-vulnerability-index-highlights-city-hot-spots/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Wolf, T.; McGregor, G. The development of a heat wave vulnerability index for London, United Kingdom. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2013, 1, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabrin, S.; Karimi, M.; Nazari, R. Developing vulnerability index to quantify urban heat islands effects coupled with air pollution: A case study of Camden, NJ. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, A.M.; Rachid, A. Heat vulnerability index mapping: A case study of a medium-sized city (Amiens). Climate 2022, 10, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Li, Z.; Gao, Y.; Liu, X.; Xu, L.; Vardoulakis, S.; Yue, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q. A systematic review of the development and validation of the heat vulnerability index: Major factors, methods, and spatial units. Curr. Clim. Chang. Rep. 2021, 7, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Meier, F.; Lee, X.; Chakraborty, T.; Liu, J.; Schaap, M.; Sodoudi, S. Interaction between urban heat island and urban pollution island during summer in Berlin. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 636, 818–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Google Earth Engine. Available online: https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/LANDSAT_LC08_C02_T1_L2 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Google Earth Engine. Available online: https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/ECMWF_CAMS_NRT?hl=fr (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Google Earth Engine. Available online: https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/COPERNICUS_S5P_OFFL_L3_O3?hl=fr (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Google Earth Engine. Available online: https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/MODIS_061_MCD12Q1?hl=fr (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Muncipality of Toulouse. Available online: https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/2011101?geo=FRANCE-1 (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Pascal, M.; Wagner, V.; Lagarrigue, R.; Casamatta, D.; Pouey, J.; Vincent, N.; Boulanger, G. A yearly measure of heat-related deaths in France, 2014–2023. Discov. Public Health 2024, 21, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/airq (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training. Available online: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/news/france-new-study-highlights-adult-basic-skill-gaps-and-training-needs (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Public Health France. Available online: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/ (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Karwat, A.; Franzke, C.L. Future projection of heat mortality risk for major European cities. Weather Clim. Soc. 2021, 13, 913–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weather Toulouse, Meteo France. Available online: https://meteofrance.com/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Air Quality Toulouse, ATMO France. Available online: https://www.atmo-occitanie.org/ (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- US. National Science Foundation. Available online: https://www.nsf.gov/news/risk-death-surges-when-extreme-heat-air-pollution (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Zhao, L.; Lee, X.; Smith, R.B.; Oleson, K. Strong contributions of local background climate to urban heat islands. Nature 2014, 511, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santamouris, M. Cooling the cities—A review of reflective and green roof mitigation technologies to fight heat island and improve comfort in urban environments. Sol. Energy 2014, 103, 682–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, B.; Vargo, J.; Habeeb, D. Managing climate change in cities: Will climate action plans work? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 107, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Groups | Risk Factors | Data Source/Software/Model |

|---|---|---|

| Heat Exposure: degree to which location experiences high surface temperature. | Land surface temperature—30 m | Landsat 8 [19] |

| Heat sensitivity: the extent to which people are likely to be negatively affected by heat exposure, depending upon environmental and demographic factors | Air quality (PM10, PM2.5, and O3)—1 km2 | ECMWF/CAMS/NRT and Sentinel-5P [20,21] |

| LULC (NDVI, NDWI, NDBI)—900 m | MODIS and Landsat 8 [19,22] | |

| Population density (4325/km2) | INSEE [23] | |

| Elderly population age 65+ (14.5%) | - | |

| Socially isolated (6%) | - | |

| Mortalities (heat and pollution) | Literature and AirQ+ [24,25] | |

| Adaptive capacity: the ability of communities to adapt with heat risks influenced by social and economic conditions. | Illiteracy rate (4%) | Europa [26] |

| Poverty rate (22%) | INSEE [23] |

| Parameter | Formula | Nomenclature |

|---|---|---|

| NDVI | Band 3: GREEN Band 4: RED Band 5: NIR (near-infrared) Band 6: SWIR (shortwave infrared) represents random forest logic to assign classes based on indices’ bands : Vegetation fraction TB: brightness temperature from thermal band m approximate wavelength for Landsat 8 (band 10) : Radiative constant surface emissivity | |

| NDWI | ||

| NDBI | ||

| LULC | ||

| LST | ||

| HVI |

| Year | LULC—Coverage (%) | Air Quality µg/m3—Mean | LST (°C)—Mean | HVI—Coverage (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetation | Built-Up | Water Bodies | O3 | PM10 | PM2.5 | |||

| 2021 | 34 | 61 | 5 | 63.5 | 12 | 8.03 | 43 | VH = 28 H = 50.6 M = 16.2 L = 5.2 |

| 2022 | 18.7 | 75 | 6.3 | 71 | 14 | 12.1 | 42.1 | VH = 33.2 H = 40.5 M = 22.6 L = 3.7 |

| 2023 | 31 | 57 | 12 | 72 | 12.9 | 7.7 | 39.75 | VH = 35.9 H = 40.9 M = 15.8 L = 7.4 |

| 2024 | 29.2 | 59 | 11.8 | 69.7 | 12.8 | 8.3 | 36.9 | VH = 18.9 H = 48.5 M = 22.4 L = 10.2 |

| 2025 | 23.4 | 63 | 13.6 | 71.2 | 11.85 | 7.1 | 39.35 | VH = 20.4 H = 34.3 M = 33.8 L = 11.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qureshi, A.M.; Sioud, K.; Zaaoumi, A.; Debono, O.; Bhatia, H.; Ben Taher, M.A. Spatiotemporal Assessment of Urban Heat Vulnerability and Linkage Between Pollution and Heat Islands: A Case Study of Toulouse, France. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 541. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120541

Qureshi AM, Sioud K, Zaaoumi A, Debono O, Bhatia H, Ben Taher MA. Spatiotemporal Assessment of Urban Heat Vulnerability and Linkage Between Pollution and Heat Islands: A Case Study of Toulouse, France. Urban Science. 2025; 9(12):541. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120541

Chicago/Turabian StyleQureshi, Aiman Mazhar, Khairi Sioud, Anass Zaaoumi, Olivier Debono, Harshit Bhatia, and Mohamed Amine Ben Taher. 2025. "Spatiotemporal Assessment of Urban Heat Vulnerability and Linkage Between Pollution and Heat Islands: A Case Study of Toulouse, France" Urban Science 9, no. 12: 541. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120541

APA StyleQureshi, A. M., Sioud, K., Zaaoumi, A., Debono, O., Bhatia, H., & Ben Taher, M. A. (2025). Spatiotemporal Assessment of Urban Heat Vulnerability and Linkage Between Pollution and Heat Islands: A Case Study of Toulouse, France. Urban Science, 9(12), 541. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120541