From Heritage Valuation to Evidence-Based Computational Heritage Town Planning: Methodological Development and Application of the Cultural Heritage Town Development Index

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To review and synthesize existing heritage valuation and assessment approaches to identify conceptual and methodological evolution,

- To develop a multidimensional framework that integrates conservation, social, infrastructural, economic, environmental, and revenue-related aspects of heritage towns contributing towards heritage-sensitive urban planning,

- To test the application of the framework and check its diagnostic capacity in identifying sectoral strengths, challenges, and role in governance and development planning.

- It conceptualizes heritage towns as living socio-economic systems and develops a comprehensive six-dimensional assessment model that moves beyond conventional heritage valuation approaches.

- It provides a systematically constructed and empirically validated composite index that enables evidence-based planning, resource allocation, and sectoral prioritization.

- Through the application to two contrasting Indian heritage towns, the study demonstrates the diagnostic capacity of CHTDI to reveal sectoral strengths, developmental trade-offs, and policy-level directions.

2. Theoretical Background: Evolution of Heritage Assessment Approaches

2.1. Early Stage—Tangible and Intangible Heritage Valuation

2.2. Intermediate Stage—Economic and Tourism-Led Models

2.3. Integrated Stage—Multidimensional Heritage Value Assessment

| S. No. | Assessment Approach | Objective | Dimensions Assessed | Remarks | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Travel Cost Method (TCM) Although proposed in 1947, it came into heritage-specific application in early 2000s. | Estimate recreational/heritage site value via visitor travel expenditure | Tangible heritage; tourism demand | Ignores social, environmental, governance aspects; assumes access value only | [5] |

| 2 | Market Pricing Approach Applied in real estate valuation of heritage-listed properties from 1970s onwards | Capture monetary value of heritage assets through comparable market prices | Economic/real estate | Limited to market-active properties; excludes non-use and cultural values | [19] |

| 3 | Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) Widely used in infrastructure since 1950s; heritage projects by 1980s–1990s | Compare monetary benefits vs. costs of preservation projects | Economic; financial | Non-market values difficult to capture; heritage often undervalued | [5] |

| 4 | Contingent Valuation Method Proposed in 1963 and widely used in heritage since 1980s–1990s | Estimate willingness-to-pay for preservation; non-use values | Intangible; economic valuation | Survey-based, risk of bias; context-specific | [5,20] |

| 5 | Hedonic Pricing Early use in property markets (1960s); applied to heritage property premiums since 1990s | Estimate property price differentials due to heritage status or proximity | Economic (property value) | Narrowly economic; does not reflect cultural/social significance | [5] |

| 6 | Input–Output model Proposed in 1936, applied to cultural/heritage impact since 1980s–1990s | Estimate direct, indirect, and induced economic impacts of heritage/tourism on regional economies | Economic flows; employment; sectoral linkages | Static; short-term; ignores social/environmental heritage values | [21] |

| 7 | Economic Impact model Widely used in heritage/tourism studies since 1990s–2000s | Quantify multiplier effects of heritage-related spending on local/regional economy | Economics (jobs, output, income) | Often tourism-centric; neglects governance, social equity, environmental impacts | [6] |

| 8 | World Economic Forecasting Model Origin in 1960s, applied in macro-forecasting; used as context in heritage–economy studies in early 2000s | Forecast national/regional macroeconomic impacts | Economy-wide | Very general; heritage link indirect | [22] |

| 9 | Choice-based logit model Applied as McFadden’s random utility theory in 1970s, having application in heritage studies since 2000s–2010s | Elicit preferences for heritage conservation strategies | Social preferences; economic | Complex design; requires strong statistical modelling | [23] |

| 10 | UNESCO Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) Approach Adopted by UNESCO in 2011 | Integrate heritage into wider urban development planning | Social; environmental; governance; cultural | Normative; lacks quantitative operationalization | [2] |

| 11 | SoPHIA (Social Platform for Holistic Heritage Impact Assessment) model Developed 2020 (EU Horizon 2020 project) | Holistic heritage impact assessment across multiple domains | Social; governance; economy; environment; culture | Framework-level; needs testing at local scales | [10] |

| 12 | CLIC (Circular models Leveraging Investments in Cultural heritage) Model (Circular/Adaptive Reuse) EU Horizon 2020 project | Evaluate adaptive reuse and circular economy in heritage sites | Environmental; economic; cultural | Case-specific; limited transferability | [24] |

| 13 | Culture-Based Development (CBD) model—2021 | Link cultural capital with entrepreneurship and local economic growth | Economic; cultural; social | Still conceptual; limited empirical validation | [11] |

| 14 | LED (Local Economic Development) Model—2021, where the pilot project was conducted in Cape Town | Assess role of heritage/tourism in local employment and growth | Economic; local development | Narrow scope; heritage treated as tourism sub-sector | [25] |

| 15 | Spatial Computable General Equilibrium (S-CGE) Models—2022 | Economy-wide modelling of heritage/tourism interventions | Economic (macro-regional) | Data-intensive; not heritage-specific | [26] |

| 16 | Global livability index Launched by Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) in 2007 | Rank cities by “liveability” using stability, healthcare, culture, environment, education, infrastructure | Social; infrastructure; environment | Broad city-scale; lacks heritage/town-specific measures | [27] |

| 17 | Rapid Assessment Toolkit Asian Development Bank, 2015 | Quick diagnostics for heritage/tourism projects | Economic; policy | Simplified; lacks depth for comprehensive heritage valuation | [28] |

| 18 | Ease of Living Index, India Introduced by Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, Govt. of India, 2018, where the components were updated further in 2019 | Benchmark quality of life in Indian cities across 13 categories | Quality of life; governance; sustainability; economy | City-level; excludes heritage and cultural assets | [29] |

| 19 | Municipal Performance Index Launched by MoHUA (Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, India), 2019 | Evaluate performance of municipalities in service delivery, governance, finance, planning | Governance; service delivery; finance | Not heritage-specific; urban management tool | [30] |

| 20 | Urban sustainability index 2013 | Assess urban sustainability (environment, social, economic dimensions) | Environment; economy; social sustainability | Generic urban index; not heritage-specific | [31] |

2.4. Gaps in Existing Models

3. Development of the Cultural Heritage Town Development Index (CHTDI)

3.1. Conceptual Foundation

3.2. Methodology

3.2.1. Identification of Relevant Parameters That Contribute to the Cultural Heritage Economy

3.2.2. Expert Opinion Survey and Analysis

3.2.3. Criteria Development Using Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

3.3. Structure of the Index

4. Application of CHTDI

5. Discussion

- Community integration in governance: Establishing local heritage management committees (mandated under HUL and encouraged under the 74th CAA decentralization framework) to increase awareness and participation.

- Revenue diversification: Developing cultural enterprises (craft hubs, and Tagore-inspired creative industries) supported by schemes like MSME support and Startup India.

- Infrastructure enhancement: Integrating Shantiniketan into national and state-level development schemes for water, sanitation, and green mobility projects to strengthen physical byproducts.

- Tourism management: Introduction of a Heritage and tourism Development Plan aligned with West Bengal Tourism Policy, with capacity management and visitor taxes earmarked for conservation.

- Formal recognition and listing of heritage structure, especially in the temple precincts and allied cultural landscape.

- Transport and crowd management: Incorporation into national schemes as extended phase for intelligent mobility systems, pedestrianization, and green corridors to address congestion during peak pilgrimage periods.

- Cultural entrepreneurship: Further encouraging cultural cooperatives around local festivals, handicrafts, and devotional music, supported by state-level cooperative development boards and aim for global recognition and involvement.

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Panasyuk, M.; Pudovik, E.; Malganova, I.; Butov, G. Historical heritage factor in evaluating development prospects of the regional multicultural community. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 188, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonia, G.; Girard, L.F. Multicriteria tools for the implementation of historic urban landscape. Qual. Innov. Prosper. 2017, 21, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripp, M. A Metamodel for Heritage-Based Urban Development: Enabling Sustainable Growth Through Urban Cultural Heritage; Springer Nature: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Hakimi, H.A.; Azmi, N.F.; Li, K.; Duan, B. A Framework for Heritage-Led Regeneration in Chinese Traditional Villages: Systematic Literature Review and Experts’ Interview. Heritage 2025, 8, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merciu, C.F.; Petrisor, A.I.T.; Merciu, G.L. Economic Valuation of Cultural Heritage Using the Travel Cost Method: The Historical Centre of the Municipality of Bucharest as a Case Study. Heritage 2021, 4, 2356–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, W.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, Z.; Gong, Z. Management effectiveness evaluation of world cultural landscape heritage: A case from China. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; García-Badell, G.; Rodriguez, J.B. Digital Heritage from a Socio-Technical Systems Perspective: Integrated Case Analysis and Framework Development. Heritage 2025, 8, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martine, B.; Toro, P.D.; Girard, L.F.; Gravagnuolo, A.; Iodice, S. Indicators for ex-post evaluation of cultural heritage adaptive reuse impacts in the perspective of the circular economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, C.; Aminreza, I. Protection Boundary Development in Historical–Cultural Built Environments Using Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) and Geographic Information System (GIS). Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rida, A.; Weigl, A.; Wieser, A.; Baioni, M.; Demartini, P.; Marchirori, M. The SoPHIA model and its implementation. Econ. Della Cult. 2021, 32, 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Y. A Behavioral Cultural-Based Development Analysis of Entrepreneurship in China. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, M.P. Heritage, Local Communities and Economic Development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 735–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, R.M.F.; Costa, C.; Ferreira, A.M. Multidimensional benefits of creative tourism: A network approach. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasile, V.; Razvan, M.; Alexandra, I. Heritage Entrepreneurship and Ecotourism—A new vision on ecosystem protection and in-situ specific activities for cultural heritage consumption. Rev. Romana Econ. 2016, 42, 140–154. [Google Scholar]

- Nebojša, Č. International media and tourism industry as the facilitators of socialist legacy heritagization in the CEE region. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandra, P.; Reddy, S.B. Benchmarking Bangalore City for Sustainability—An Indicator-Based Approach; Indian Institute of Science: Bangalore, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Elika, T.; Pancholi, S.; Rashid, M.M.; Khoo, C.K. Cultural heritage sites as a facilitator for place making in the context of smart city: The case of Geelong. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ost, C.G. A Guide for Heritage Economics in Historic Cities: Values, Indicators, Maps, and Policies; Think City Institute: Penang, Malaysia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kurowski, L.; Rodawski, B.; Sztanzo, A.; Ladysz, J. Selected Methods of Estimation of the Cultural Heritage Economic Value with Special Reference to Historical Town Districs Adaptation. In Urban Heritage: Research, Interpretation, Education; Vilnius Gediminas Technical University Publishing House: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2007; pp. 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, A.S.; Ritchie, B.W.; Papandrea, F.; Bennett, J. Economic valuation of cultural heritage sites: A choice modeling approach. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surugiu, C. The Economic Impact of Tourism. An Input-Output Analysis. Rev. Romana De Econ. 2009, 29, 142–161. [Google Scholar]

- Beaussier, T.; Caurla, S.; Bellon-Maurel, V.; Loiseau, E. Coupling economic models and environmental assessment methods to 4 support regional policies: A critical review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 216, 408–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D.; Zednik, A.; Araña, J.E. Public preferences for heritage conservation strategies: A choice modelling approach. J. Cult. Econ. 2021, 45, 333–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravagnuolo, A.; Bosone, M.; Girad, L.F. Deliverable D2. 5–Methodologies for impact assessment of cultural heritage adaptive reuse. Retrieved May 2023, 30, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Garidzirai, R.; Nguza-Mduba, B. Does tourism contribute to local economic development (LED) in the City of Cape Town Municipality? A time series analysis. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2020, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. Wider Economic Impact Assessment with a S-CGE Model; High Speed Two (HS2) Limited: Birmingham, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- RaviSree, P.; Brar, T.S. A Critical Review of Livability and Identifying the Models for its Measurement. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 6, 6832–6841. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, B.H. Tool Kit for Rapid Economic Assessment, Planning, and Development of Cities in Asia; Asian Development Bank: Mandaluyong City, Philippines, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- MoHUA. Ease of Living—2018; Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs: New Delhi, India, 2018.

- MoHUA. Ease of Living—2019; Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs: New Delhi, India, 2019.

- Li, S.; Kyllo, J.M.; Guo, X. An integrated model based on a hierarchical indices system for monitoring and evaluating urban sustainability. Sustainability 2013, 5, 524–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lequeux-Dincă, A.I.; Gheorghilaş, A.; Tudor, E.A. Empowering urban tourism resilience through online heritage visibility: Bucharest case study. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surugiu, M.-R.; Surugiu, C. Heritage tourism entrepreneurship and social media: Opportunities and challenges. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 188, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuhrt, D.P.; Weiss-Ibanez, D.F. Cognitive processing of information with visitor value in cultural heritage environments. Econ. Financ. 2014, 15, 303–311. [Google Scholar]

- da Costa, R.A.; Almeida, L.F.; Chim-Miki, A.F.; Brandao, F. Identifying social value in tourism: The role of sociocultural indicators. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2025, 62, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, A.; Khan, Z.A.; Gani, A.; Asjad, M. Identification, ranking and prioritization of Key Performance Indicators for evaluating greenness of manufactured products. Green Technol. Sustain. 2025, 3, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.R.; Alam, M.J.; Tabassum, N.; Khan, N.A. A Systematic Review of the Delphi–AHP Method in Analyzing Challenges to Public-Sector Project Procurement and the Supply Chain: A Developing Country’s Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Chatterjee, P.; Das, P.P. Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Methods in Manufacturing Environments: Models and Applications; Apple Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Volume 1, p. 450. [Google Scholar]

- SSDA. Land Use & Development Control Plan-2025 for Sriniketan–Santiniketan Planning Area; Sriniketan–Santiniketan Development Authority: Bolpur, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

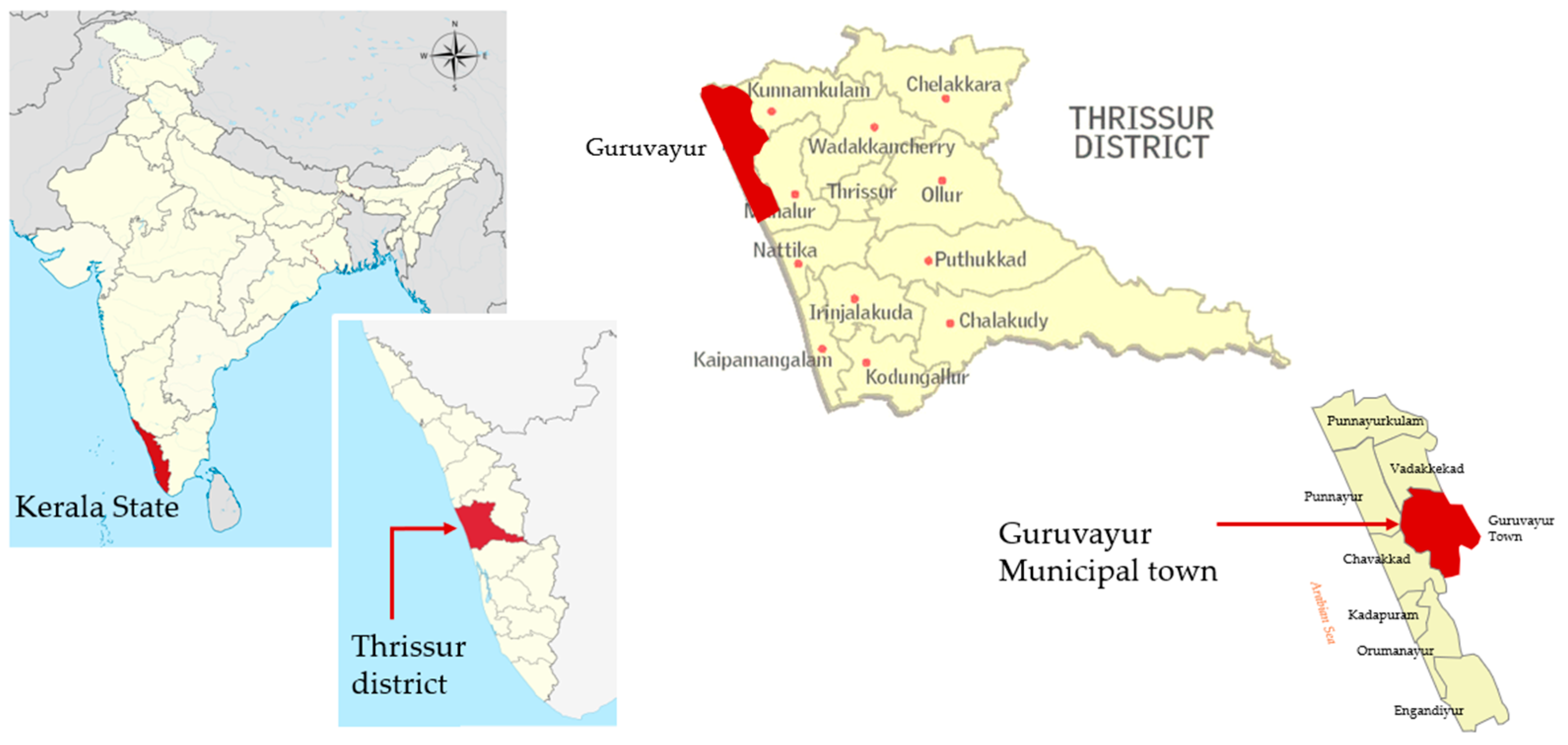

- Guruvayur, M.C. Master Plan for Guruvayur Town—2039; Local Self Government Department Kerala: Thiruvananthapuram, India, 2022.

- Vinod, V.; Sarkar, S.; Roy, S. An Overview of Key Indicators and Evaluation Tools for Assessing Economic Value of Heritage Towns: A Literature Review. J. Inst. Eng. (India) Ser. A 2024, 105, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MoUD. Heritage City Development and Augmentation Yojana; Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2014.

- MoT. Pilgrimage Rejuvenation and Spiritual Augmentation Drive; Ministry of Tourism, Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2014.

- MoUD. Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation; Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2015.

- Vinod, V.; Sarkar, S.; Roy, S. Proposed Methodological Framework for Assessing the Economic Value of Heritage Town and Local Economic Phenomena. In Exploring Culture and Heritage Through Experience Tourism; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; Volume 1, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter Code I | Parameter | Delphi Survey (Rating) | Final Code | Mean | Median | Mode | Std. Dev | Variance | Normalized Assigned Weights | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Stage | 2nd Stage | |||||||||

| P1 | Number of Heritage Resources | Accepted | Accepted | HR1 | 4.267 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 0.889 | 0.791 | 4.00 |

| P2 | Significance of Heritage Resources | Accepted | Accepted | HR2 | 4.467 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 0.786 | 0.618 | 5.00 |

| P3 | Geographical Location | Accepted | Accepted | HR3 | 4.356 | 4.000 | 5.000 | 0.773 | 0.598 | 2.00 |

| P4 | Condition/Quality of HR. | Accepted | Accepted | HR4 | 4.244 | 4.000 | 4.000 | 0.743 | 0.553 | 3.00 |

| P5 | Conservation Initiatives | Combined with P6 | 6.00 | |||||||

| P6 | Heritage Management and Maintenance | Accepted | Accepted | HR5 | 4.444 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 0.725 | 0.525 | |

| P7 | Demography | Accepted | Accepted | SP1 | 3.733 | 4.000 | 4.000 | 1.009 | 1.018 | 3.00 |

| P8 | Awareness and Satisfaction | Combined with P9 | _ | 6.50 | ||||||

| P9 | Community Participation | Accepted | Accepted | SP2 | 4.667 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 0.707 | 0.500 | |

| P10 | Travel and Tourism | Accepted | Accepted | SP3 | 4.889 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 0.383 | 0.146 | 3.50 |

| P11 | Connectivity and Transportation | Accepted | Accepted | PP1 | 4.778 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 0.517 | 0.268 | 4.50 |

| P12 | Telecommunication and ICT | Rejected | _ | |||||||

| P13 | Utilities | Accepted | Accepted | PP2 | 4.489 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 0.695 | 0.483 | 5.50 |

| P14 | Tourism Infrastructure | Accepted | Accepted | PP3 | 4.800 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 0.588 | 0.345 | 4.00 |

| P15 | Commercial Activities | Rejected | ||||||||

| P16 | Recreational Activities | Accepted | Accepted | PP4 | 4.600 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 0.751 | 0.564 | 3.00 |

| P17 | Employment | Accepted | Accepted | EB1 | 4.711 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 0.506 | 0.256 | 3.50 |

| P18 | Cultural Entrepreneurship | Accepted | Accepted | EB2 | 3.956 | 4.000 | 4.000 | 0.903 | 0.816 | 6.50 |

| P19 | Social Impact | Accepted | Accepted | SP4 | 4.756 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 0.712 | 0.507 | 6.50 |

| P20 | Environmental Impact | Accepted | Accepted | EV1 | 4.844 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 0.520 | 0.271 | 3.00 |

| P21 | Economic Impact | Accepted | Accepted | EB3 | 4.733 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 0.720 | 0.518 | 8.50 |

| P22 | Cultural Vibrancy | Rejected | _ | |||||||

| P23 | Creativity and Innovativeness | Rejected | _ | |||||||

| P24 | Indirect and Induced Impact in Town | Rejected | _ | |||||||

| P25 | Employment Generation due to heritage | Rejected | _ | |||||||

| P26 | Heritage Significance and Attractiveness | Rejected | _ | |||||||

| P27 | Direct Revenue Generation | Accepted | Accepted | EE1 | 4.711 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 0.727 | 0.528 | 8.00 |

| P28 | Local Economy | Rejected | _ | |||||||

| P29 | Labor Market | Rejected | _ | |||||||

| P30 | Ease of Doing Business | Accepted | Accepted | EB4 | 4.689 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 0.596 | 0.356 | 6.00 |

| P31 | Investments/Funding Assistance | Accepted | Accepted | EE2 | 4.756 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 0.645 | 0.416 | 8.00 |

| P32 | Funding Support | Combined with P31 | _ | |||||||

| P33 | GDP/GVA | Rejected | _ | |||||||

| Eigen Value 1, Varimax | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter Code I | Parameter | Component | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| P1 | No. of Heritage Resources | 0.193 | 0.763 | −0.109 | 0.204 | 0.076 | 0.248 |

| P2 | Significance of Heritage Resources | 0.233 | 0.451 | 0.1315 | 0.438 | 0.378 | 0.027 |

| P3 | Geographical Location | 0.059 | 0.522 | 0.448 | −0.370 | 0.204 | 0.117 |

| P4 | Condition/Quality of Heritage Resources | 0.170 | 0.862 | −0.137 | 0.048 | −0.112 | 0.195 |

| P5 | Conservation and Management Initiatives | −0.090 | 0.827 | 0.229 | −0.044 | 0.187 | 0.245 |

| P7 | Demography | 0.141 | 0.099 | 0.093 | 0.880 | −0.020 | 0.137 |

| P8 | Public Awareness and Community Participation | 0.421 | 0.155 | 0.104 | 0.488 | 0.415 | −0.433 |

| P10 | Travel and Tourism | 0.078 | 0.034 | 0.052 | 0.822 | 0.056 | 0.009 |

| P11 | Connectivity and Transportation | 0.698 | 0.014 | 0.174 | 0.452 | 0.221 | 0.083 |

| P13 | Utilities | 0.795 | 0.013 | 0.149 | 0.182 | 0.152 | 0.026 |

| P14 | Tourism Infrastructure | 0.731 | 0.075 | 0.068 | 0.144 | 0.267 | −0.060 |

| P16 | Recreational and Cultural Activities | 0.607 | 0.193 | 0.094 | 0.130 | 0.285 | −0.466 |

| P17 | Employment | −0.212 | 0.054 | −0.051 | 0.054 | 0.713 | 0.299 |

| P18 | Cultural Entrepreneurship | 0.067 | −0.013 | 0.237 | −0.150 | 0.717 | 0.013 |

| P19 | Social Impact | 0.148 | 0.130 | 0.034 | 0.825 | 0.077 | 0.115 |

| P20 | Environmental Impact | −0.012 | 0.001 | −0.256 | 0.106 | 0.026 | 0.783 |

| P21 | Economic Impact | 0.309 | 0.062 | 0.384 | −0.048 | 0.587 | −0.018 |

| P27 | Direct Earnings | 0.294 | −0.072 | 0.579 | 0.103 | 0.184 | −0.055 |

| P30 | Ease of Doing Business | 0.495 | 0.361 | 0.000 | 0.190 | 0.498 | −0.266 |

| P31 | Investments/Funding Assistance | 0.013 | 0.075 | 0.779 | 0.202 | 0.037 | −0.251 |

| Criteria | Code | Parameters (Parameter Code I) | P.Cr. Wt. | Indicators | Calculation/Benchmarking Methodology/Interpretation | Shantiniketan | Guruvayur |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HERITAGE RESOURCES | HR1 | No. of Heritage Resources (P1) | 1.80 | Number of World Heritage Sites (CWH), intangible (ICH) practices recognized by UNESCO/INTACH/ASI/LSGA | Zero: 0.00, 1–5: 0.50, 6 and above: 1 | 1.00 | 0.50 |

| HR2 | Significance of Heritage Resources (P2) | 4.60 | Graded heritage resources by INTACH/ASI/LSGA [Grade I-5/Grade II-3/Grade III-1] | Grade value × number Zero: 0.00, 1–5: 0.1, 6–20: 0.2, 21–40: 0.4, 41–60: 0.6, 61–80: 0.8, 81+: 1.0 | 0.60 | 0.20 | |

| HR3 | Geographical Location (P3) | 2.10 | Favorable months for tourism, frequency of disaster in past 10 yrs (min 0, max 6 national disasters) | Average of [1 − (x − 0)/(5 × 6) − 0] + [x/12] | 0.25 | 0.54 | |

| HR4 | Condition/Quality of Heritage Resources (P4) | 1.50 | Condition of built heritage based on assessment considering the conserved, abandoned, and dilapidated structures | <0.30: Poor, 0.31–0.50: Fair, >0.50: Good, >0.75: Excellent | 0.75 | 0.82 | |

| HR5 | Conservation and Management Initiatives (P5) | 3.50 | Conservation initiatives, presence of management units, guidelines and regulations etc. | 0.0–0.25: Weak, 0.26–0.50: Moderate, 0.51–0.75: Good, 0.76–1: Excellent | 0.90 | 0.75 | |

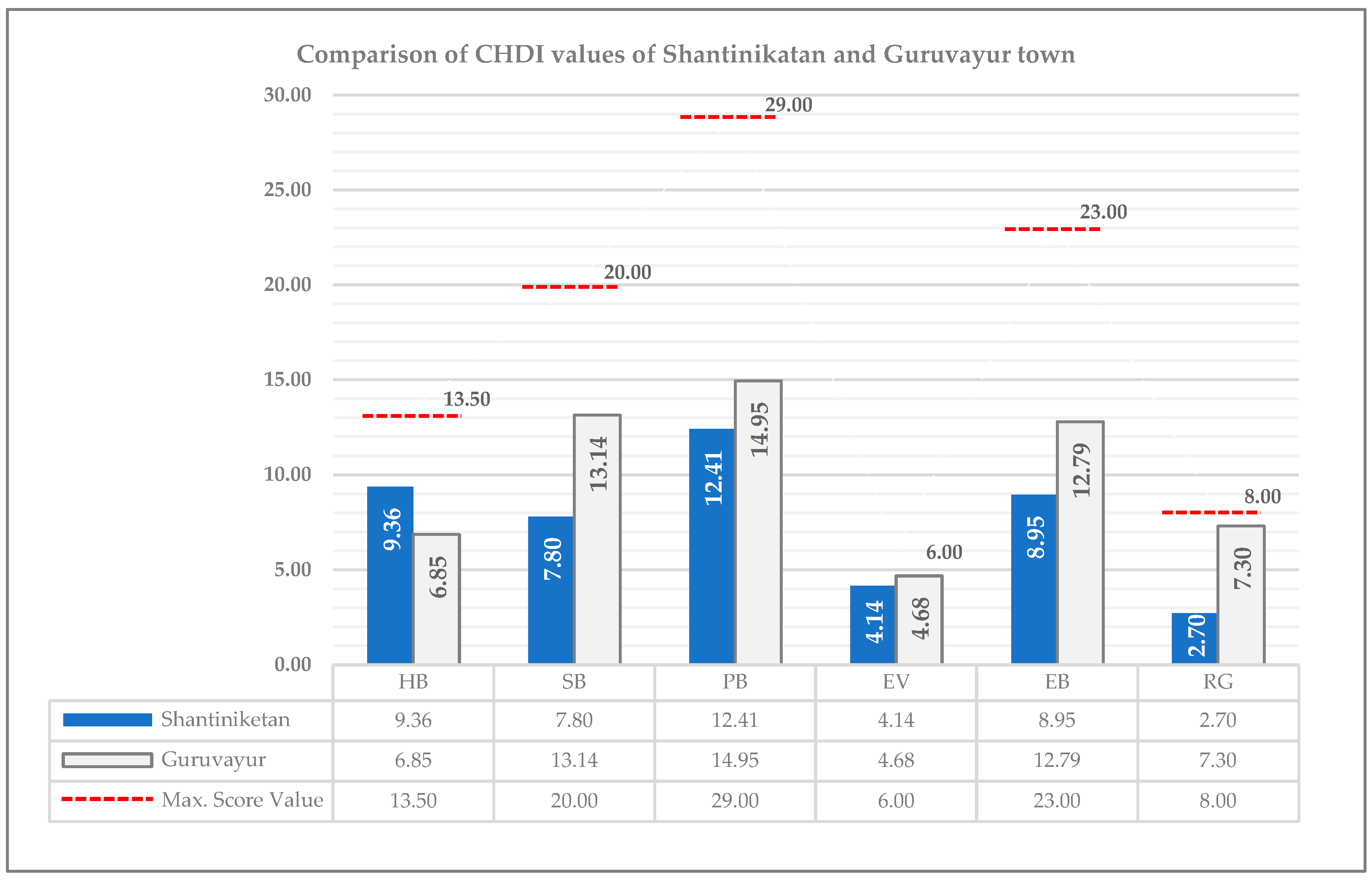

| HRCITY | (Equation (2)) | 13.50 | 9.360 | 6.854 | |||

| SOCIAL BYPRODUCTS | SB1 | Demography (P7) | 1.70 | Population size, growth rate (min 0, max 100) and density (min 1000, max-5000), literacy (min 0, max 100) | Average value of normalized values using respective minimum and maximum values | 0.54 | 0.55 |

| SB2 | Public Awareness and Community Participation (P8) | 6.30 | Willingness to participate, presence of heritage communities, collaborative opportunities, etc. | <0.20: Very Poor, 0.21–0.40: Poor, 0.41–0.60: Moderate, 0.61–0.8: Good, >0.80: Excellent | 0.54 | 0.89 | |

| SB3 | Travel and Tourism (P10) | 8.30 | Travel characteristics, tourist footfall, etc. | Normalization using min–max method and weighted average | 0.25 | 0.68 | |

| SB4 | Social Impact (P19) | 3.70 | Contribution to aesthetics, harmony and safety; concept of heritage tax credits, H-TDR, etc. | <0.20: Very Poor, 0.21–0.40: Poor, 0.41–0.60: Moderate, 0.61–0.8: Good, >0.80: Excellent | 0.38 | 0.26 | |

| SBCITY | (Equation (3)) | 20.00 | 7.801 | 13.148 | |||

| PB1 | Connectivity and Transportation (P11) | 13.50 | Mobility hubs for connectivity, frequency and accessibility, digital connectivity, healthcare | Normalization using min–max method and weighted average <0.20: Very Poor, 0.21–0.40: Poor, 0.41–0.60: Moderate, 0.61–0.8: Good, >0.80: Excellent | 0.27 | 0.35 | |

| PHYSICAL BYPRODUCTS | PB2 | Utilities (P13) | 5.00 | Water supply, electricity, sewage, sanitation | 0.78 | 0.80 | |

| PB3 | Tourism Infrastructure (P14) | 7.50 | Tour operators, availability and accessibility of accommodation etc. | 0.46 | 0.65 | ||

| PB4 | Recreational and Cultural Activities (P16) | 3.00 | Open spaces, frequency of recreational activities, vibrancy of the town etc. | 0.47 | 0.45 | ||

| PBCITY | (Equation (4)) | 29.00 | 12.405 | 14.950 | |||

| ECONOMIC BACKDROP | EB1 | Employment (P17) | 9.30 | Participation rate, cultural sectors ratio etc. | Normalization using min–max method and weighted average <0.20: Very Poor, 0.21–0.40: Poor, 0.41–0.60: Moderate, 0.61–0.8: Good, >0.80: Excellent | 0.22 | 0.24 |

| EB2 | Cultural Entrepreneurship (P18) | 4.00 | Willingness to contribute, skill development, ratio of cultural entrepreneurship sector etc. | 0.48 | 0.64 | ||

| EB3 | Ease of Doing Business (P30) | 6.60 | Support from business networks, programs for skill development, national and global level opportunities | 0.69 | 0.95 | ||

| EB4 | Economic Impact (P21) | 3.60 | Benefit to local businesses, real estate value | 0.12 | 0.48 | ||

| EBCITY | (Equation (5)) | 23.50 | 8.952 | 12.790 | |||

| ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT | EV | Environmental Impact (P20) | 6.00 | Quality of air, water, land etc., contribution to biodiversity enhancement/reverse the loss | Normalization using min–max method and weighted average <0.20: Very Poor, 0.21–0.40: Poor, 0.41–0.60: Moderate, 0.61–0.8: Good, >0.80: Excellent | 0.69 | 0.78 |

| EVCITY | (Equation (6)) | 6.00 | 4.140 | 4.680 | |||

| REVENUE GENERATION | RG1 | Direct Earnings (P27) | 2.80 | From tourist sites, cultural and souvenir shops, restaurants, etc. | 0.1–2 Cr: Poor (0.25), 2–5 Cr: Moderate (0.5), 6–10Cr: Good (0.75), 11cr+: Excellent (1) * for population of max. 50,000 | 0.50 | 0.75 |

| RG2 | Investments/Funding Assistance (P31) | 5.20 | Financial assistance for city-level development, tourism hubs, entrepreneurial development, etc. | 0.1–5Cr: Poor (0.25) 5–10 Cr: Moderate (0.50), 11–20 Cr: Good (0.75), 20cr+: Excellent (1) * for well-known heritage towns < Tier II towns. | 0.25 | 1 | |

| RGCITY | (Equation (7)) | 8.00 | 2.700 | 7.300 | |||

| Cultural Heritage Town Development Index (CHTDI)—(Equation (1)) | 45.358 | 59.722 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vinod, V.; Sarkar, S.; Roy, S. From Heritage Valuation to Evidence-Based Computational Heritage Town Planning: Methodological Development and Application of the Cultural Heritage Town Development Index. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120514

Vinod V, Sarkar S, Roy S. From Heritage Valuation to Evidence-Based Computational Heritage Town Planning: Methodological Development and Application of the Cultural Heritage Town Development Index. Urban Science. 2025; 9(12):514. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120514

Chicago/Turabian StyleVinod, Varsha, Satyaki Sarkar, and Supriyo Roy. 2025. "From Heritage Valuation to Evidence-Based Computational Heritage Town Planning: Methodological Development and Application of the Cultural Heritage Town Development Index" Urban Science 9, no. 12: 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120514

APA StyleVinod, V., Sarkar, S., & Roy, S. (2025). From Heritage Valuation to Evidence-Based Computational Heritage Town Planning: Methodological Development and Application of the Cultural Heritage Town Development Index. Urban Science, 9(12), 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120514