1. Introduction

Climate change and its associated effects constitute an important threat for the environment, the economy and human society. In this context, the global increase in temperature and extreme weather events pose important challenges for the safety, well-being and health of the population [

1], especially for those living in high-density urban areas. According to CDP Worldwide [

2], around 93% of the world’s cities face significant climate risks, and, in particular, those related to intense storms and floods, episodes of extreme heat or cold, and prolonged periods of drought.

Cities need to pinpoint the specific factors that make them vulnerable to climate change and weather phenomena and identify the impacts on the population and the most effective measures they can take to reduce risk and increase resilience [

3,

4]. The cities that are progressing towards climate resilience have a policy of active adaptation and institutional structures that encourage and support action to transform, from the inside, the systems for coping with climate change. Their response to climate change involves a range of different measures in which according to some researchers [

5,

6,

7], short-term solutions tend to be more prevalent than long-term strategies. Climate shelters offer a collective solution in the short-to-medium term applied at a local scale, which enables local people to deal with the risks arising from extreme weather events [

8,

9,

10].

Climate shelters are spaces fitted out for public use in natural or built environments, which offer environmental conditions of comfort and security so that local people can protect themselves from adverse weather conditions, such as, for example, excessive cold or heat, or floods. The climate shelter concept first appeared in the United States in the 1990s. In the Mediterranean region, Barcelona was the first city to set up a network of climate shelters and is now a reference in Europe and the world over, along with cities such as Paris, London, New York, Amsterdam and The Hague.

As happens with research into other aspects of climate adaptation [

11,

12,

13], the studies monitoring the climate shelter networks established in different cities around the world focus on the processes and the quantitative advances in the implementation of these measures (number of shelters created, resources devoted to it) and the policies implemented to achieve this goal. The institutions that promote and manage these adaptation projects use these monitoring studies as general indicators of progress, and place little emphasis on analysing the results of the different measures implemented (effective use of the shelters). The mere fact that these spaces exist in the city and are growing in number does not mean that people can make proper use of them during critical weather events. As documented in previous research, there are several different variables affecting their use. For example, in research in a poor neighbourhood in Barcelona, Amorim et al. [

14] found that when extreme weather events occur, the structural vulnerabilities arising from the precarious nature of housing and from energy poverty are exacerbated by the small

number of these adaptation infrastructures (climate shelters) in the neighbourhood. Pede [

15] analysed the role played by the

location of climate shelters in Turin in the promotion of social justice in climate adaptation, presenting proposals for a better distribution of infrastructures of this kind. On similar lines, other research studies also confirmed that the number and location of the climate shelters did not always coincide with the spatial distribution of the different demographic and socioeconomic segments of society, so creating climate adaptation problems for the most vulnerable groups [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

In research on two important urban areas in the United States (Los Angeles County in California and Maricopa County in Arizona), Fraser et al. [

23] emphasized how the

temporal and spatial accessibility (physical) of these infrastructures can affect their use at critical moments in time, revealing in their case studies that climate shelters are not always optimized for maximizing access. On the same subject, Nayak et al. [

20] evaluated the access of vulnerable populations in the state of New York to “cooling centers”, considering various means of transport; the results of their research highlighted that rural areas were in a worse situation than urban ones, emphasizing the importance of planning to improve access and eliminate barriers.

The

types of spaces used as shelters also influence the way they are used. Different studies suggest that although green, cool, accessible and well-equipped spaces can be efficient shelters during very hot days, local residents tend to prefer other alternative spaces [

24,

25,

26,

27]. On these lines, Vasconcelos et al. [

28] analysed the role played by public green spaces as nature-based climate shelters for senior citizens living in the city of Barcelona. Their results indicate that most of the senior citizens interviewed visit green spaces as a way of protecting themselves from the heat, preferring urban parks with large shaded areas, lush vegetation, good access and suitable facilities (fountains, benches and toilets). However, the study also revealed that these people tend to visit these spaces in the mornings or evenings, so avoiding the hottest times of the day and staying there for a short time. This shows that this segment of the population prefers other methods for coping with high temperatures.

The lack of information about the adaptation strategies implemented at the local level also affects the use of these climate shelters.

Information and cognitive barriers can prevent potential users of shelters from using them, putting the advances in adaptation and the effectiveness of the solutions implemented in jeopardy. If we are aware of the available options in the area we live in, it makes it easier for us to take the tactical decisions required to deal with threats from extreme weather events [

29,

30,

31]. Adaptation measures are less effective if they are not accompanied by a public information process which publicizes the existence and location of the shelters and raises levels of awareness about the risks associated with extreme weather, the ultimate aim being to encourage the use of these facilities developed to reduce the exposure of city residents to climate-related dangers [

32,

33,

34].

Huitema et al., Javeline et al. and Pahl-Wosts [

35,

36,

37], among others, have revealed that failings in adaptation to climate change are closely related to problems of governance. According to Patterson [

38], in the institutions for the governance of cities, adaptation to climate change may be carried out in different ways: through the creation and reform of legislative frameworks, the design of policies, the introduction of instruments for implementing these policies, the creation or repurposing of organizations involved in the adaptation processes and, finally, through the promotion of coordination and collaboration agreements (at different levels and between different public and private bodies), so as to ensure successful adaptation. On the basis of his review of the literature on each of these forms of adaptation, this author identified in the implementation instruments a set of four indicators, one of which was communication, which enabled him to empirically measure adaptation to climate change in 96 cities across the world. These indicators had differing levels of importance in the adaptation processes of the cities studied:

planning had a very prominent role,

mainstreaming and

communication had moderately prominent roles, while

incentives were of very limited importance [

38]. This moderate level of importance given to communication in climate governance at a local scale could be at the root of the failure of adaptation in many of the world’s cities [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. The gaps in the information provided in communication about adaptation processes and the relatively minor role given to communication in climate governance could be a barrier to effective public participation in these processes [

42,

43,

44]. The minor or moderate levels of prominence given to communication in the adaptation processes implemented by official institutions for city governance could undermine the important efforts being made by these institutions in other forms of adaptation linked to planning, the modification of legal or regulatory frameworks or the development of new policies, to cite just a few examples.

The effective deployment at a local scale of an adaptation strategy aimed at reducing the vulnerability of the population and strengthening their resilience to extreme weather events requires a goal-oriented information and communication plan. In the particular issue we are dealing with here, the priority objective of the information and communication plan should be to publicize the climate shelter network at project level, and to explain its purpose, the location of the nodes in the network and their availability so that potential users can make use of them in crisis situations. As a basic premise, if the potential users of the network have no knowledge of the project, its purpose, the location of the nodes (shelters) and their availability, it will be difficult for them to sign up to or participate in the adaptation strategy and make proper use of the climate shelters. The information provided to potential users of climate shelters could influence their response, given that detailed knowledge of any government action is a necessary precondition to ensure public participation in it. Communication is important and must be taken into account within governance so as to maximize the effectiveness of improvements made to legal and regulatory frameworks, policies and planning, and also to take maximum advantage of the emergence of a new scenario for collaboration and assignment of the responsibilities arising from the current context of climate emergency.

Research studies specifically analysing how cities communicate their climate-related actions have found that the information about adaptation provided by the institutions basically offers: (a) broad-based approaches about how to deal with climate change; (b) general information on policies, adaptation plans and resilience at a local scale; and (c) information about organizational and bureaucratic efforts to change the model for the city in the face of climate change [

45,

46]. These broad-based, generalized climate communication contents end up becoming more and more prominent in local brand communication, in the city’s place branding efforts, so creating a scenario in which climate communication is more likely to respond to the city’s marketing interests than to the specific needs of climate action [

47,

48]. This is why some research studies have proposed the need to highlight in climate communications the specific solutions or actions being taken at a local level so as to be able to guide city residents in the taking of decisions that make adaptation possible. It is crucial for communication to encourage public participation, commitment and hope [

49,

50].

With regard to the effectiveness and use of climate shelters, there has been no specific research into the information and cognitive variables, factors that need to be considered in processes for improving climate action. Communication is a key factor for facilitating the implementation of adaptation measures because it improves people’s understanding of the risks of climate change and of the available options for adaptative responses [

41,

51]. In this context, the objective of this research is to examine the level of public knowledge of the development of the climate shelter network in the city of Barcelona, and the degree to which the population has signed up (use and rating of the network) to this adaptation strategy. Barcelona’s climate shelter network is a reference worldwide which means that it is important to evaluate the results of its implementation, analysing whether the enthusiasm of the local administration for increasing the number of shelters in the city is in harmony with the capacity (knowledge) of local residents to make best use of these options. The findings of this research could be used to improve communication, a key aspect in the city’s climate governance. The results could be a useful guide for all cities, Barcelona included, that are implementing or improving adaptation strategies based on climate shelters, in this way contributing to the improvement of the mechanisms for the control and monitoring of the measures implemented.

2. Study Area and Methodology

2.1. The Climate Shelter Network in Barcelona

Barcelona, a city with an area of 102 km2 and a population of 1,702,547 (2024) has a climate shelter network that has been increasing in size ever since its creation in 2020. During its first year, it consisted of just 70 such facilities and 20% of the city’s population had a climate shelter within 5 minutes’ walking distance. In 2023, this network had grown to 232 facilities, and the percentage of the population it covered had increased to 59%. In 2024, the number of shelters increased even further to over 300 (354) all over the city, such that 68% of the population had a shelter within 5 minutes’ walk.

The climate shelter network in the city of Barcelona is made up of many different types of shelter (2024): 52 libraries, 23 sports complexes, 11 museums, 7 churches, 108 local social facilities and others (civic centres, cultural centres, senior centres, neighbourhood centres, youth clubs), 3 environmental education centres, 1 Barcelona Social Emergency and Urgency Centre, 46 parks and gardens, 17 municipal markets, 2 shopping centres, 4 cultural organizations, 1 university, 18 interior “islands” or inner block courtyards, 9 school playgrounds, 8 nursery school playgrounds and 44 municipal swimming pools (these are not free). These climate shelters are distributed around the different districts of the city as can be seen in

Table 1.

Barcelona’s climate shelter network allows the population to take shelter from extreme temperatures, both hot and cold. In research on Europe over the period 1991–2020, García-León et al. [

52] calculated an annual average of 363,809 cold-related and 43,729 heat-related deaths. As regards the latter, Gallo et al. [

53] highlighted that in 2023, over 47,000 people died in Europe as a consequence of high temperatures, estimating that the mortality rate related with extreme heat would have been up to 80% higher if no adaptation strategy had been implemented. The number of deaths attributable to heat in the city of Barcelona in the same year was 300, and according to a recent study [

54], Barcelona will be the city with most deaths due to excess heat in Europe by the end of this century. It is therefore evident that adaptation measures and actions can play a key role in the current context in which the climate crisis is intensifying.

Climate governance in the city of Barcelona, articulated around the Climate Plan 2018–2030 (Plan Clima 2018–2030) is a multidimensional strategy designed to coordinate policies, legal frameworks, implementation instruments (for planning, communication actions, etc.) and resources to ensure the successful adaptation to and mitigation of climate change, involving civil society, public institutions, companies, visitors, etc. The city’s climate shelter network arose from Barcelona City Council’s Climate Plan 2018–2030 and was designed as a fundamental adaptation strategy in the current climate context in Barcelona, and also in a future context in which heat and extreme temperatures will intensify, becoming the dominant features of the city’s climate. For a scenario in which the emissions reduction targets set out in the Paris Agreement are achieved, the Barcelona Climate Emergency Action Plan (El Plan de acción para la emergencia climática de Barcelona) of 2021 contemplated an increase of 1.7 °C in the annual temperature in the city by the end of the century, an average of 50 hot days a year (maximum temperature of over 30 °C), an average of 2.5 extremely hot days a year (maximum temperature of over 35 °C), an average of 83 tropical nights a year (minimum temperature of over 20 °C), an average of 2.5 extremely hot nights a year (minimum temperature of over 25 °C) and two heatwaves every year. However, in a passive scenario in which the Paris Agreements were not achieved, they predicted an increase of 3 °C in the average annual temperature by the end of the century, with the averages increasing to 80 hot days a year, 8.5 extremely hot days a year, 112 tropical nights a year, 6 extremely hot nights a year and between four and five heatwaves a year. The increase in temperatures, the aging of the city’s population and its intensive urban development, which increases the impact of extreme heat, highlight the urgent need to act.

The rollout of the shelter network has been accompanied by a corresponding investment in communication, highlighting how important it is within the context of climate governance. The payments made to the different media that have carried out publicity campaigns about the climate shelters in the city of Barcelona account on average for around 70.2% of the total investment in communication in this project. Of this 70.2%, almost 45% was spent on radio advertisements, around 22% in online news outlets and around 33% on branded content. The aim of the radio advertisements is to provide general information about the climate shelter network. This medium allows excellent geographical segmentation and thanks to the variety of radio stations and programmes, different groups of people can be targeted with high precision, so enabling a high-pressure publicity and information campaign with a high frequency of contacts in very short periods of time (summer or crisis periods). With regard to online media (online news outlets), these can raise awareness and inform the public about the existing adaptation strategies in the city, reaching a wide audience and allowing readers to interact through, for example, links to the city council’s websites, which contain more detailed information about these projects. The branded content includes a set of techniques used by brands (in this case Barcelona City Council) to connect with their target audience through creative content that adds value. In this case, the value was generated through informative contents created by the Council itself. In a strict sense, it could be argued that the main objective of the branded content is not so much to inform the population about the existence of a climate shelter network, but more to position the brand (Barcelona City Council) as a local administration that is working to ensure adaptation to climate change.

The investment in production, distribution and photography comes to an average of 21.4% of the total investment in communication. This includes the printing of posters and leaflets, free gifts distributed via street marketing in key periods of activation of the information campaigns, the installation of billboards, the distribution of materials and photography.

Lastly, the money spent on creative publicity and adapted advertisements about climate shelters in the city of Barcelona came to an average of around 8.4% of total investment in communication. These payments were made to advertising agencies approved for making “master creativity” and adapting the content to each support or medium.

2.2. Design of the Survey and Selection of the Sample Group

The survey technique was used to assess the level of public knowledge about the development of the climate shelter network in the city of Barcelona, and the degree to which the population has signed up to this adaptation strategy (use and rating of the network). For this purpose, a questionnaire with closed questions was drawn up.

The questionnaire was administered to a sample group of city residents. The theoretical size of the sample group depended on the population variance values (maximum uncertainty, p = 50% and q = 50%), the confidence level (S ± 2σ of the average value of the normal distribution curve, which encompasses 95.5% of the possible answers) and the sampling error (E ± 5.7%). In this way, the sample size was calculated using the formula for an infinite population. The result was 296. In view of this result, we decided to conduct face-to-face surveys with a sample group of 300 people (response rate 100%).

The questionnaires were administered by stratified random sampling. In this statistical method, the population is divided into subgroups, in this case corresponding to the different city districts. Three climate shelters in each of the ten districts in the city of Barcelona were selected at random, so establishing a total of 30 climate shelters as sampling points. The sample group covered all the different types of shelter currently available. In each one, the people surveyed were chosen at random. The fact that the interviews were carried out at the climate shelters themselves did not bias the selection process in that these facilities all had other principal functions that pre-existed their use as climate shelters (for example as libraries, parks, places of worship, etc.). The survey campaign was carried out between May and September 2024 In line with the General Regulations on Data Protection (RGPD) (EU Regulation 2016/679), verbal informed consent was obtained from the participants. The survey guarantees the anonymity of the participants and therefore does not contain any directly identifiable personal data.

The questionnaire was organized into three different blocks of questions. The questions in the first block sought to assess the knowledge of city residents about the functioning of the climate shelter network in the city of Barcelona and its roll-out at general project level and in more specific detail. It also contained questions about the ways they had obtained this information. The second block investigated the interviewees’ use and preferences regarding the different facilities in the network. Finally, the third block included questions to assess various different aspects, such as how inclined or likely they were to use the shelters (participation in the solution), the roll-out of the network and the communication campaigns. The answers to the questionnaires were analysed using descriptive statistics. In this way, this approach provides an initial general view that helps identify elements of interest, which could later serve as a basis for future more specific analyses. For example, multivariant analyses could be conducted on the basis of the essential socioeconomic information gathered (district of residence, sex, age group, level of studies and employment situation). These would enable us to analyse possible underlying intersectional differences regarding knowledge and use of climate shelters in the city of Barcelona.

Of the 300 people surveyed, 33% were men and 67% were women. 32% of those surveyed were aged between 45 and 64, 30% were over 65 and 28% were aged between 25 and 44. 54% of those surveyed had a university degree, followed by people with secondary studies (31%). More than half the people surveyed were currently working (54%), while 29% were retired.

3. Results

3.1. Knowledge of the City’s Climate Shelter Network

Of the 300 people surveyed, 64% said that they knew there was a climate shelter network in the city of Barcelona, while 36% indicated that they were unaware of its existence. Most of the surveyed (68%) stated that they did not know that most of the facilities designated as climate shelters in Barcelona also functioned during the winter season.

The people that claimed to know about the climate shelter network in Barcelona said that they obtained this information from different sources and on occasions from more than one (this question had a multiple-choice answer): 39% had found out about the climate shelters through the television, press or radio; 27% said that they discovered them from the signage on the facilities designated as climate shelters; 25% mentioned that they had done so through information leaflets or advertisements in the public space; 15% said that they had received the information from family members, friends or other people, while 11% mentioned social networks. Finally, 2% said that they had discovered the shelters through the website and 9% through other unspecified means.

In order to uncover more specific results, the respondents were asked whether they were aware that the facility in which the survey was taking place was a climate shelter. The results show that most of them were unaware of this: 59% stated that they did not know that the facility provided this function, while 41% said that they did know.

When the respondents were asked if this was the first time they had visited this facility, the vast majority (88%) said that they had visited it previously, while 12% said that it was their first visit. Of the former, 64.4% visited the facility regularly, 30.3% did so occasionally and 5.3% visited it rarely. Another interesting statistic was that a considerable percentage of the frequent users of these facilities (56%) were unaware of their status as climate shelters.

3.2. Use and Preferences for Use of the City’s Climate Shelter Network

A total of 68% of respondents stated that they had used a facility in the city to shelter from extreme temperatures. By contrast, 32% indicated that they had never used a facility for this purpose.

Of the people who indicated that they had used a facility in this city for this purpose, 53% stated that the place they had used was an officially designated climate shelter. However, 38% were not sure if the space actually belonged to the network and 9% stated that the place they had used was not an official climate shelter.

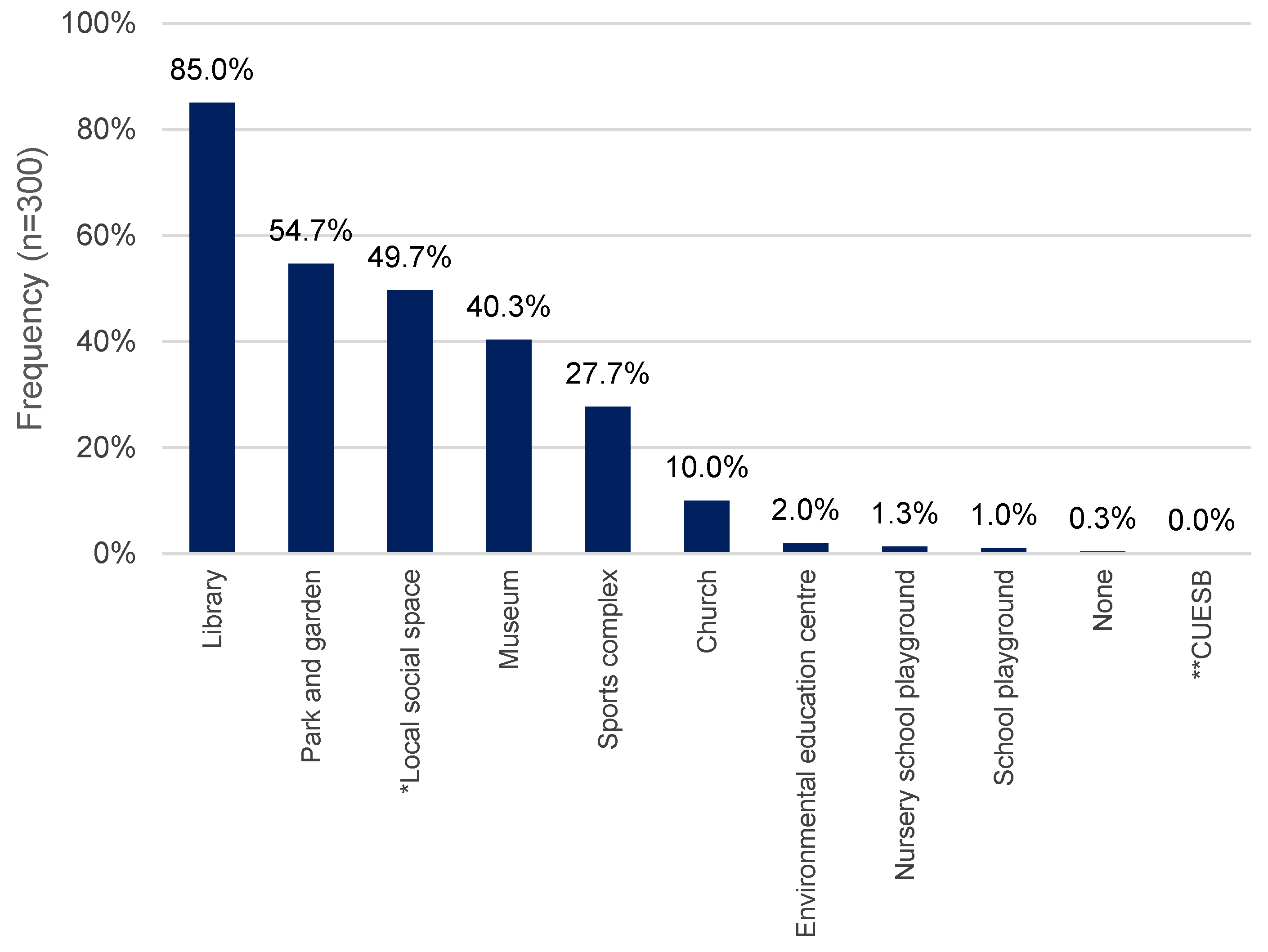

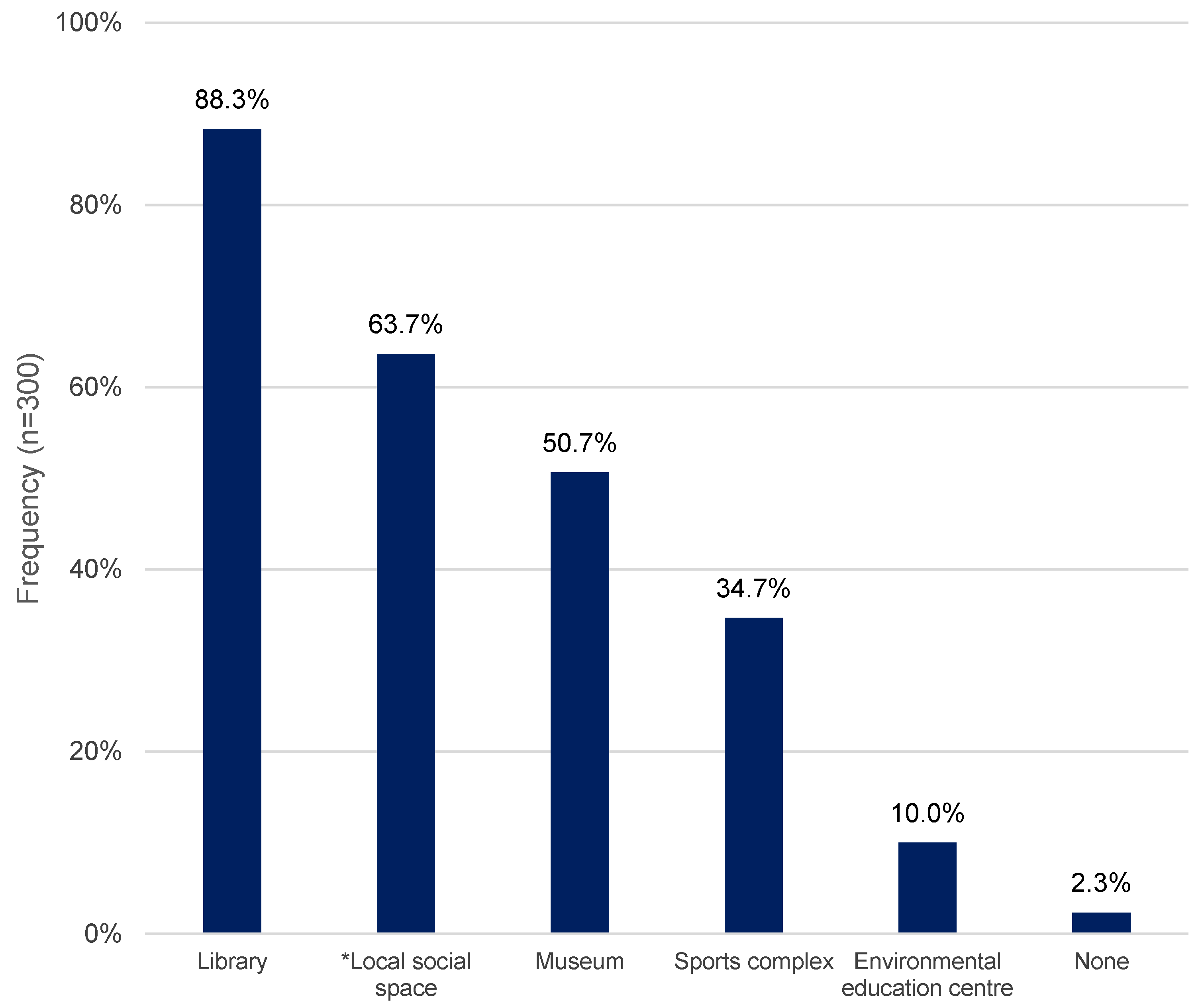

The vast majority of the respondents, 88%, said that they would consider using a climate shelter during a heatwave or a very cold spell. By contrast, just 3% said that they would not, while 9% said that they were not sure whether they would use the shelters in such circumstances. As regards the types of climate shelter that they would prefer to use during hot days, libraries, parks and gardens were the most frequently selected options (

Figure 1). As regards their preference on cold days, the most common were libraries and local social spaces, such as civic centres, senior centres, neighbourhood centres, etc., (

Figure 2).

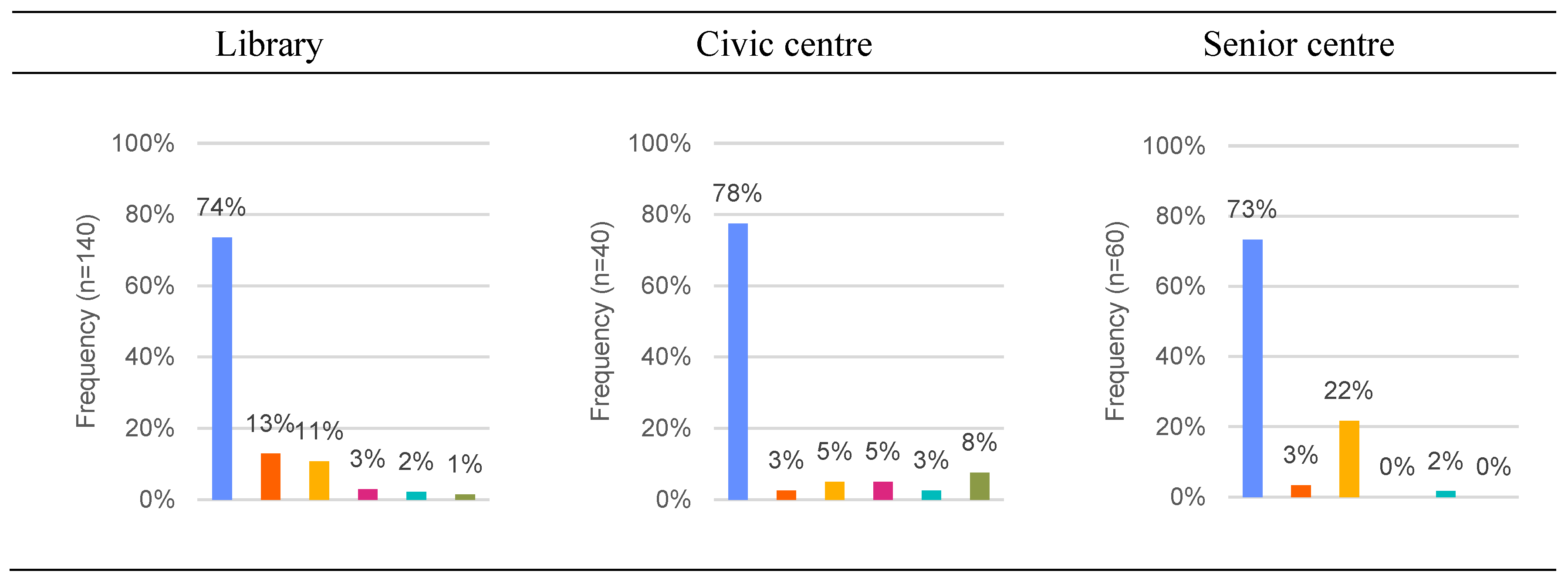

When consulted about whether they had ever used the climate shelter in which the survey was taking place in order to shelter from the heat or cold, 20% said that they had used it at some stage to protect themselves both from the heat or the cold; 33% said that they had only used it to shelter from the heat, while 2% said that they had only used it to shelter from the cold. The remaining 45% indicated that they had never used the space for either of these purposes. The results highlight great variety if analysed by type of facility (

Figure 3).

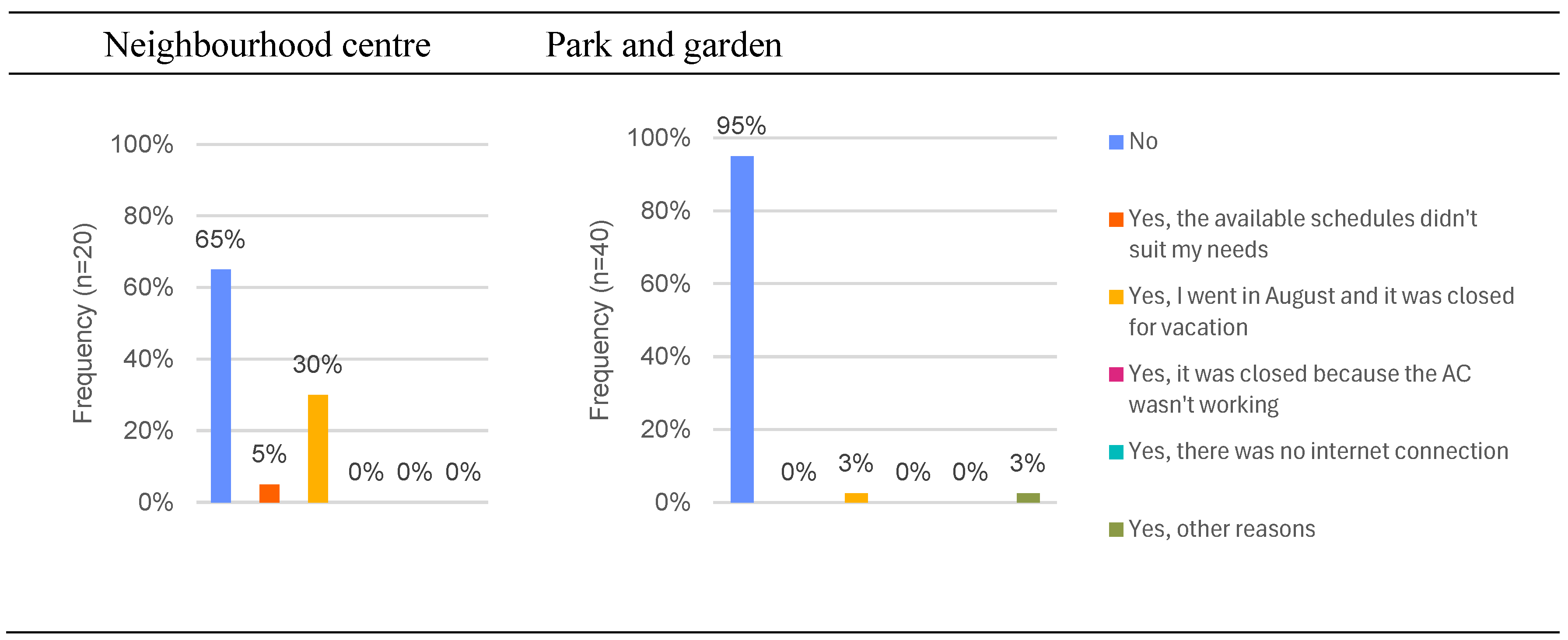

Most respondents stated that they have never encountered obstacles of any kind and very few have come up against impediments to using the facility (

Figure 4).

3.3. Opinions About the City’s Climate Shelter Network

In terms of respondents’ opinions regarding the dimensions of the city’s climate shelter network, the results highlight a significant lack of knowledge about the number of nodes in the network and their distribution at district level. Most of those surveyed (66%) said that they did not know whether there was a sufficient number of shelters in the city. Only 11% believed that the current number was sufficient, while 23% believed that there was an insufficient amount of climate shelters in the city of Barcelona. With regard to their distribution at district level, 60% of the respondents indicated that they did not know whether their particular district was sufficiently equipped, once again reflecting their lack of knowledge or detailed information on this subject, and 17% stated that there was a sufficient number of shelters in their district, while 23% said that this was not the case.

When asked about their opinions regarding the importance or usefulness of the shelters in Barcelona as part of the strategy of adaptation to climate change, the respondents showed a very high level of agreement: 98% said that the shelters network was an important part of the efforts being made to adapt the city; 1% said that the opposite was true and the remaining 1% did not know what to say. Similarly, when asked about the importance of the network in crisis situations such as heatwaves or cold spells, 97% answered “yes”, 1% “no” and 2% did not know what to answer. As regards usefulness, most answers were very positive: on a scale of 1 to 5 (where 1 was “of very limited use” and 5 “very useful”), 50% gave the maximum score, 33% gave a score of 4, 14% of 3; and the rest of less than 3.

The respondents expressed negative opinions about the information and communication campaigns conducted in relation to the climate shelters network and its rollout in the city. 51% offered negative opinions and 6% very negative. Just 34% had positive opinions about the measures. 9% answered “Don’t know/Don’t answer”. The results also reflected widespread criticism of the communication strategies used (57% rated them negatively or very negatively). Just 34% offered positive opinions. 9% did not answer.

The respondents were asked to rate the facility where they were as a climate shelter on a scale of 1 to 5, in which 1 was the minimum value (very bad) and 5 the maximum (excellent). The results revealed that most of the opinions were positive. 43% graded the space as excellent, 42% as very good and 12% as good. Just 2% offered negative opinions.

Most of those respondents (91%) regarded the space where they were being surveyed as a viable option for sheltering from a heatwave, while just 9% said that they would not use it for that purpose. Regarding whether they would consider the facility as an option for combatting cold weather, 71% said that they would bear it in mind, while 29% said that they would not consider it as a means of protecting themselves against low temperatures.

Lastly, when asked whether they would recommend the facility to other people as a space to shelter from extreme climate conditions, 92% answered affirmatively, while just 8% said that they would not do so. This high level of recommendation indicates high levels of confidence amongst the majority of the respondents in the usefulness and effectiveness of the facility as a climate shelter.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This study analyses the level of public knowledge regarding the development of the climate shelter network in the city of Barcelona, and the degree of public acceptance (use and rating of the network) of this climate change adaptation strategy. More research into these issues is required due to the lack of key information in the communication contents and the relatively minor role that communication plays in climate governance. This could act as an obstacle to the effective participation of members of the public in adaptation processes [

42,

43,

44]. In cases in which communication is given a moderate or lesser role in the adaptation processes implemented by the institutions of urban governance, this can undermine or neutralize the important efforts being made by these institutions via other forms of adaptation [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42].

The results of the study highlight that the mere existence of such facilities in the city does not guarantee that they can be used effectively by its residents as a strategy for adaptation to extreme temperatures. The level of knowledge, arising in part from the information provided to potential users and the communication strategies employed to this end, can be an important barrier to or effective promoter of its use. This finding enables us to add this factor to the list of variables that must be taken into consideration in the effective rollout of climate change adaptation strategies and as an indicator in monitoring reports. Insufficient knowledge of these measures by potential users may weaken their effectiveness, as may the insufficient number of shelters [

14,

55,

56], their unsuitable location and distribution [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22], accessibility to facilities in terms of opening times and spatial distribution [

20,

23], or inappropriate selection of types of spaces [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

55].

The paper highlights that although general information about the existence of a network has reached the residents of Barcelona, the detailed information about the rollout of the network at city and district level has been clearly insufficient. The people of Barcelona are very much aware of the risks associated with climate change and are well-disposed to participate in the adaptative solutions. However, not everyone can make use of these solutions as they do not know enough about them. The people of Barcelona have serious difficulties in identifying the nodes in the network so as to enable them to use them at times of need. The level of information provided to the public has prioritized general information ahead of detail, so raising people’s awareness of the risks associated with climate change [

49,

50], while weakening the chances of them making use of these adaptative solutions. Within the framework of the climate governance of the city, climate-related communication aimed at achieving specific objectives must be strengthened, so as to encourage the use of climate shelters during extreme weather events.

The information disseminated in publicity campaigns has been more focused on positioning the City Council as an institution that works in favour of climate action and less on encouraging the use of climate shelters by local people. This question highlights how the general contents of climate-related communication have become increasingly important in Barcelona’s place branding, leading us to conclude that climate communication is spurred more by the Council’s desire to boost the local brand than by their interest in promoting adaptation. These findings confirm those of previous authors [

47,

48] and are also manifested in the allocation of funding to different forms of communication, as set out in the budget of Barcelona City Council. The emphasis on branded content and wide-reach advertising campaigns on the radio and in online press can successfully raise public awareness about the need to adapt and inform people about the project in general terms, but is not appropriate for communicating detailed information about the network.

The study has revealed that the citizens of Barcelona are well aware of the risks associated with climate change, in particular in relation to extremely hot temperatures. This means it is more likely that the public will take self-protection measures and other adaptation options offered by the institutions. Our research shows that people are well-disposed to using these facilities, something that would justify the measures taken by the Council to increase the number of shelters in the network. However, the effects of this increase will not be reflected in their use if the citizens, as has been demonstrated in our research, do not know where they are. The policy of increasing the number of facilities must be accompanied among other things by solid information campaigns and suitable communication strategies. Communication is a key factor in the city’s climate governance and must therefore be managed appropriately, so as to ensure the success of the climate change adaptation solutions rolled out in Barcelona. Only in this way can all the efforts be reflected in a greater use of these shelters and in a reduction in the numbers of deaths in the city that can be attributed to heat.

The findings of this research enable us to propose certain improvements that would increase the knowledge and encourage the use of climate shelters in times of crisis. To this end, we recommend that the campaigns of a general nature be maintained (through radio, online media and branded content in the press) in order to continue raising awareness amongst the population regarding the risks associated with excessive heat and publicizing the adaptation strategy being implemented by the City Council. These campaigns must be complemented with other communication strategies that offer the residents detailed information that enables them to take tactical decisions. So far, such strategies have received less attention from the Council, which is why we recommend that they be stepped up. To this end, we advise the sending out of detailed information about the nodes in the network, via an institutional mailing campaign based on leaflets and flyers (with maps and lists of the climate shelters with addresses and opening and closing times). This would allow all homes to receive direct information in physical form that could be very useful in moments of crisis. We also recommend more investment in information panels and billboards (map and list of all the shelters), which could be distributed in strategic points in the different districts of the city. We propose that these information panels and billboards be located in busy places in the districts with easy access (markets, bus shelters, entrances to Metro stations, etc.) and not only in the facilities that have been assigned as climate shelters.

The results presented here can be used by decision-makers in questions involving climate shelters in Barcelona and could contribute to a better design of an information and communication campaign that improves the city’s climate governance. This research provides a general initial view that enables us to identify elements of interest that may be of use in more specific future analyses. The findings encourage us to continue investigating how cognitive and communication variables affect the rollout of effective measures for combating climate change at a local scale, while taking into consideration their variation in relation to different sociodemographic and economic variables in the city. In this line of research, as is the case with the implementation of other adaptation measures [

57], it is essential to involve the local population so as to be able to develop a communication strategy that guarantees universal access to specific, detailed information that increases public acceptance and use of adaptative solutions.