Abstract

Understanding how environmental design and institutional trust shape perceived security in nightlife settings is essential for enhancing customer experiences and business sustainability. This study examines how surveillance, access control, territoriality, maintenance, and trust in police influence customers’ perceptions of security in nightlife establishments in Colombia, and how these perceptions affect satisfaction and revisit intentions. A survey was conducted involving 400 customers in nightlife venues in Guadalajara de Buga, using Likert scales to evaluate the constructs. Data were analyzed using partial least squares structural equation modeling; Results indicate that maintenance (β = 0.304), surveillance (β = 0.264), trust in police (β = 0.203), and territoriality (β = 0.184) significantly influence perceived security, while access control does not. Perceived security strongly impacts satisfaction (β = 0.662) and revisit intention (β = 0.641). The model explains 47% of the variance in perceived security, 43% in satisfaction, and 41% in revisit intention. These findings highlight the value of integrating environmental design and institutional trust within service marketing and crime prevention, showing that investments in design and maintenance can yield commercial benefits. The study offers guidance for owners seeking to improve customer satisfaction and loyalty through targeted strategies.

1. Introduction

In the current context, the perception of safety has become a determining factor for the success of commercial establishments, particularly in the nighttime tourism sector [1]. This perception does not arise in a vacuum but is intrinsically linked to broader architectural and urban planning concepts that dictate how individuals interact with their environment after dark [2]. The design of cities—such as street lighting, plaza layouts, facade visibility, and mixed land use—fundamentally shapes people’s behavior and their feelings of vulnerability or confidence [3].

This relevance is particularly heightened in regions where violence and insecurity are daily concerns, as is the case in various parts of Latin America [4]. The perception of safety not only influences the initial decision to visit an establishment but also affects the entire consumer experience, from behavior during the visit to future intentions to return and recommend the venue [5]. In the nightlife sector, which includes bars, restaurants, and nightclubs, this perception is especially critical due to factors such as operating hours, alcohol consumption, and the concentration of people in specific spaces [6].

Academic literature has extensively documented how the perception of insecurity can act as a significant barrier to the economic development of commercial and tourist areas [7]. In regions where violence or crime is perceived as a constant threat, commercial establishments face additional challenges in attracting and retaining customers [8]. This situation becomes particularly critical in the nighttime entertainment sector, where the perception of vulnerability can be intensified by the inherent conditions of the activity [9]. Owners and managers of these establishments are compelled to implement various strategies to mitigate these negative perceptions and create environments that customers consider safe and trustworthy [10].

To bridge the gap between environmental design and human behavior, Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) has emerged as a promising approach to address these concerns. Rooted in architecture and urban planning, this theoretical framework posits that the appropriate design and management of the physical environment can reduce both the actual incidence of crime and the fear of victimization [11]. The principles of CPTED—such as natural surveillance, access control, territoriality, and maintenance—have been widely studied and validated in various urban and commercial contexts [12]. However, research linking these elements to specific marketing variables, such as customer satisfaction and revisit intention, has been limited. To support this assertion, a literature review was conducted, with key findings summarized in Table 1. This table highlights that while individual components of CPTED have been studied, their integration with commercial outcomes in the nighttime entertainment sector represents a notable research gap.

Table 1.

Literature Review Summary: CPTED Constructs and Related Studies.

As observed in Table 1, existing research has primarily focused on crime prevention or the perception of security as an end in itself, leaving a gap in understanding how environmental design decisions directly translate into business outcomes for establishments such as bars, nightclubs, and restaurants. The main objective of this study is to bridge this gap by analyzing how CPTED elements, along with trust in local authorities, influence the perception of safety among customers of nightlife establishments—and how this perception, in turn, affects their satisfaction and revisit intentions.

To achieve this objective, the study is grounded in two main theoretical frameworks: CPTED and the Two-Component Basic Model (MBDC), the latter proposed by Cunningham [41], which helps understand how uncertainty and potential negative consequences interact in shaping risk perception. This objective addresses a significant gap in the current literature and offers both academic and practical contributions. From an academic perspective, this study contributes to the existing literature in several ways. First, it proposes a model that integrates two traditionally separate fields of research: crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED) and services marketing. The selection of these two frameworks responds to the need to address the problem from its causes (environmental design) and consequences (business outcomes). CPTED was chosen as the leading approach explaining how physical environmental characteristics can mitigate both crime and individuals’ perceptions of insecurity [42]. Meanwhile, services marketing is essential for measuring the impact of these perceptions on critical business variables such as customer satisfaction and loyalty [43].

The primary merit of integrating these two perspectives is that it creates a more holistic and practically applicable model. While CPTED alone focuses on prevention without necessarily quantifying its commercial return, and services marketing often treats safety as an exogenous factor, their combination demonstrates how environmental design decisions directly translate into business outcomes. Thus, the research provides a value argument that justifies investment in safety not as an operational cost but as a strategic tool to enhance customer experience and competitiveness.

Second, based on this integration, the study proposes and empirically validates a model linking specific CPTED elements to key business outcomes. Third, the model is enriched by incorporating the dimension of institutional trust. The relevance of this factor lies in the fact that the perception of safety is not constructed solely from the immediate physical environment but also from the social and governmental context [44]. Particularly in Latin American contexts, trust that authorities will act effectively and promptly is a fundamental pillar of an individual’s sense of protection [45]. Including this variable allows the study to go beyond CPTED principles, recognizing that even the safest environmental design may see its perceived effectiveness diminished if citizens lack trust in the institutions meant to safeguard it [46]. From a practical standpoint, the findings of this research can provide valuable guidance for owners and managers of nightlife establishments on how to effectively implement design and management elements that enhance their customers’ perception of safety. Additionally, the results may be useful for local authorities and urban planners in developing policies and strategies that promote safer and economically viable commercial environments.

In accordance with the above, this article is structured as follows: First, a theoretical framework integrating CPTED principles with literature on consumer behavior and services marketing is presented, along with the development of research hypotheses. Next, the methodology is described, including details on the sample, measurement scales, and analysis procedures. Following this, the results of the empirical analysis are presented, along with a discussion of their theoretical and practical implications.

2. Theoretical Framework

The perception of security in commercial establishments is a key factor influencing consumer attitudes and behaviors [47]. Particularly in the context of tourism, and more specifically in the nightlife sector, which includes bars and restaurants, the perception of criminal safety can enhance satisfaction with establishments, strengthen recommendation intentions, and even increase the likelihood of revisiting [48,49]. To explore both the antecedents and consequences of the perception of security in the hospitality sector, this theoretical framework integrates various perspectives.

First, it relies on the Two-Component Basic Model (MBDC), proposed by Cunningham [41], which provides a foundation for understanding how elements of the physical, social, and institutional environment affect customers’ perception of security. This model, validated over more than five decades, posits that perceived risk arises from the interaction between two fundamental components: uncertainty and potential negative consequences [50,51].

However, the MBDC does not specify which environmental antecedents alter this perception. To fill this gap, the proposed model integrates the principles of Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED). CPTED is a robust theoretical approach that identifies specific attributes of the built environment—such as surveillance, access control, territoriality, and maintenance—that can reduce both crime and the fear of crime [11,52]. The justification for its inclusion lies in the fact that each CPTED principle directly acts on the components of the MBDC: for example, good surveillance reduces uncertainty [53], while adequate maintenance minimizes signals of social disorder that could foreshadow negative consequences [54]. Thus, CPTED provides tangible and measurable predictors of perceived risk.

Finally, it is important to note that the physical environment does not operate in isolation but within an institutional context. Therefore, trust in local authorities is incorporated as a crucial factor [55]. Trust in the police can affect the relationship between the environment and the perception of security, acting as a safety net that reduces the perception of negative consequences even in an environment with design deficiencies [16]. The integration of these three pillars allows for the construction of a logical causal model that flows from the attributes of environmental design and the institutional context to the formation of the perception of security, ultimately measuring its impact on key business variables such as satisfaction and revisit intention.

Considering the above, the following specific hypotheses derived from this integrated framework are developed:

Surveillance, a factor derived from the CPTED model, emerges as the first fundamental element of this study, operating through two essential dimensions: visibility and illumination [56]. Visibility facilitates the natural observation of the space by residents and passersby, while illumination allows for clear observation of the environment both day and night [12]. In light of the Two-Component Basic Model (MBDC), effective surveillance could reduce uncertainty by allowing constant monitoring of the environment and minimizing the perception of potential negative consequences by facilitating a rapid response to incidents [57]. Additionally, empirical studies have shown that adequate surveillance can reduce perceived risk among consumers in commercial environments [58]. Therefore, the first hypothesis is proposed: H1: Surveillance has a positive effect on the perception of security.

Access Control, another factor considered from the CPTED model, comprises two dimensions: physical barriers and security elements. Physical barriers are structural elements designed to control access to specific spaces, such as walls, fences, and containment devices, establishing boundaries between public and private spaces [12,59]. Security elements include physical measures, technological systems, and security protocols designed to enhance the protection of a commercial establishment [12]. A clear example of this is the use of monitoring cameras, which, according to Abdullah et al. [60], significantly contribute to reinforcing the perception of control and active surveillance. Within the MBDC, access control reduces uncertainty by establishing clear boundaries and providing constant monitoring, minimizing potential consequences by making unauthorized access difficult and enabling rapid responses to incidents [61,62]. Recent studies in this regard have shown that these elements reduce the perception of vulnerability in commercial environments [63,64]. Although empirical evidence in the bar and restaurant sector is limited, it is reasonable to think that the elements composing access control could behave similarly in this commercial cluster. Therefore, it is proposed that: H2: Access control has a positive effect on the perception of security.

Territoriality, manifested through signage and landscaping, represents the expression of ownership and control over space [65] and constitutes another fundamental element of CPTED. In this context, signage refers to markers of territoriality, such as customized decorations, garden furniture, and signage that explicitly communicate that the area is private property. These elements serve as symbolic barriers that reinforce the idea that the space is under surveillance and protected. On the other hand, landscaping includes the maintenance of gardens, the balanced arrangement between green and built areas, the care of the aesthetic conditions of the environment, and the presence of additional landscaping elements located immediately outside the controlled territory, which reinforce the perception that the space is carefully managed and monitored [12]. From the perspective of the MBDC, territoriality can significantly influence the perception of security by reducing uncertainty through clear signals of ownership and control. Territoriality elements, such as Signage and landscaping, send unambiguous visual signals indicating that the space is actively managed and monitored, and therefore, it is less likely to be exposed to undesirable situations [66]. This leads to the proposal: H3: Territoriality has a positive effect on the perception of security.

The last element derived from CPTED is maintenance, understood as the set of actions and practices aimed at preserving the optimal conditions of a commercial space and its surroundings [12]. It involves the conservation of both internal spaces (cleanliness, repairs, condition of facilities) and external spaces (facades, gardens, common areas), reflecting continuous care for the space and its facilities. It is based on the Broken Windows Theory, which posits that visible deterioration of an environment can act as a catalyst for antisocial and criminal behaviors, as it conveys a sense of lack of control and social disorder [67]. When a space shows Signage of abandonment or deterioration, it creates a perception that no one cares about it, which can attract unwanted behaviors and reduce the perception of security [68]. Regarding the Two-Component Model, maintenance reduces uncertainty by demonstrating active supervision and minimizes perceived consequences by keeping spaces well-maintained and detailed [12]. Additionally, empirical research has shown that well-maintained spaces are perceived as safer than those with Signage of deterioration [69], highlighting the critical importance of maintenance in building environments perceived as safe. Therefore, it is proposed that: H4: Maintenance has a positive effect on the perception of security.

To complement the research model aimed at identifying the key factors of the perception of security in commercial establishments, a fundamental institutional element is incorporated: trust in local authorities. This factor is crucial in shaping perceptions of security, as public safety institutions play a key role in mitigating perceived risks [70]. According to Kajalo et al. [56], trust in local authorities significantly reduces uncertainty by providing a clear framework for institutional response to incidents, which, in turn, minimizes perceived negative consequences by ensuring the presence of formal protection mechanisms. In the context of the MBDC, trust in authorities acts on both elements of perceived risk: it decreases uncertainty by offering a sense of predictability and control over events and reduces potential consequences by ensuring that there are structures and protocols to handle adverse situations [71]. Although trust in authorities is not a factor directly related to the management of commercial establishments, it is evident that greater trust in institutions can generate positive effects on the perception of security within these environments. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed: H5: Trust in the Police has a positive effect on the perception of security.

The perception of security significantly influences key variables such as consumer satisfaction and revisit intention through shared psychological and social mechanisms. According to Cunningham’s Two-Component Basic Model (MBDC) (1967) [41], the perception of security reduces uncertainty and potential negative consequences, which alleviates stress and improves the experience [72]. This fosters consumer satisfaction, as individuals feel more comfortable and secure in the environment [73]. Consequently, the hypothesis is proposed: H6: The perception of security has a positive effect on consumer satisfaction.

Regarding revisit intention, the perception of security fosters a sense of control over the environment, reducing anxiety and the perception of long-term risk. This sense of control makes consumers want to return to the establishment, associating it with a stress-free and highly satisfying experience (Šerić et al., 2022) [74]. Therefore, it is proposed: H7: The perception of security has a positive effect on revisit intention.

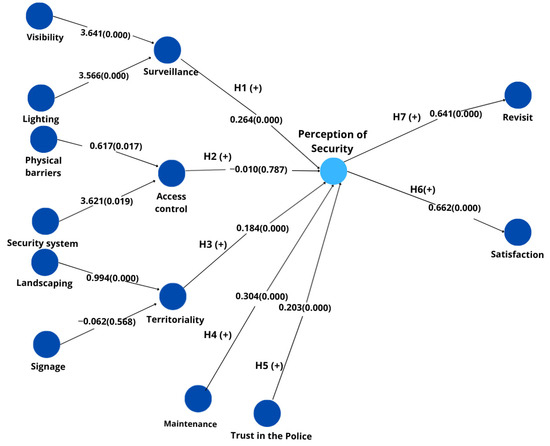

Below, in Figure 1, the formulated research model is shown.

Figure 1.

Research model.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample

For this research, a non-probability convenience sampling method was employed due to the exploratory nature of the study and the challenges in constructing a comprehensive sampling framework for the target population. Data collection was conducted in Guadalajara de Buga, a tourist city in southwestern Colombia. The study collaborated with 50 establishments, distributed as follows: 71% restaurants (n = 35), 20% bars (n = 10), and 9% nightclubs (n = 5). The selection of these businesses was not based on specific criteria such as capacity or type but rather on the willingness of the owners to allow the study to be conducted. It is worth noting that a considerable number of establishments declined to participate, citing potential discomfort for their customers, which posed a logistical challenge.

A final sample of 400 customers was obtained. The inclusion criteria for participants were twofold: being over 18 years of age and being present at the establishment at the time of the survey. No additional screening questions were used.

Regarding the procedure and ethical considerations, voluntary and anonymous participation was ensured. Before starting the questionnaire, surveyors read an informed consent statement directly from a tablet, explaining the study’s objectives and ensuring the confidentiality of responses. Participation was entirely voluntary. To safeguard privacy, no personally identifiable information, such as names or email addresses, was collected. Fieldwork was conducted from October 2024 to February 2025. During this period, surveyors approached customers in the participating establishments and asked them to complete the 20-question instrument on a tablet.

The descriptive statistics of the sample are presented in Table 2. Specifically, 59% of respondents were in the 18 to 34 age range, almost evenly distributed between 18 and 24 years (29%) and 25 to 34 years (30%). Regarding gender, there was a slight male predominance, with 59% men compared to 41% women.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of the Sample.

In terms of educational level, most participants had technical or technological training (40.8%) and secondary education (35.5%), accounting for over 75% of the sample. 20.7% had professional studies, while only 3% reported having only primary education. Finally, the sample was predominantly Colombian (94.8%), with a minority participation of foreigners (5.3%), which is consistent with the local context of the study.

3.2. Measurement Scales

The measurement instrument was developed through a process of adapting previously validated scales from the literature, which consisted of two main phases: item selection and pilot testing. In the first phase, item selection, the main criterion was the conceptual relevance of each question for the specific context of nightlife establishments in Colombia. The original scales cited [12,75], were reviewed, and items were included, seeking to avoid unnecessary repetitions and consolidating a final questionnaire of 20 items to minimize respondent fatigue and ensure the quality of the responses. For a comprehensive list of all measurement items, please refer to Appendix A (Table A1 and Table A2)

The second phase consisted of a pilot test to validate the understanding and clarity of the adapted instrument. It was carried out with a sample of 25 customers from nightlife establishments and served as a qualitative validation of the content, where feedback from participants on the wording and meaning of each question was actively sought. Based on the collected comments, minor adjustments were made to the wording of some questions to improve their intelligibility and ensure that the terms used were culturally appropriate and unambiguous before proceeding with large-scale data collection.

Most of the items were formulated as statements rated using a five-point Likert scale (from “totally disagree” to “totally agree”). However, to objectively capture the presence of specific characteristics, the items related to Access Control (CA1, CA2, CA3) and Territoriality (T1) were formulated as dichotomous (Yes/No) or count questions, as appropriate. The adapted scales included the following constructs: Trust in the police, which measures the perception of the effectiveness and reliability of the police in the area, adapted from Jang and Hwang [75]. Surveillance, evaluated from the dimensions of visibility and lighting in the establishment’s surroundings, adapted from Marzbali et al. [12]. Access control, which includes the presence of physical barriers and visible security systems, based on Marzbali et al. [12]. Territoriality, measured through Signage and landscaping in the establishment’s surroundings, adapted from Marzbali et al. [12]. Maintenance, evaluated based on the condition of the facade and other areas of the establishment, taken from Marzbali et al. [12]. Perception of security, which measures visitors’ sense of security both inside the establishment and in the surrounding area, adapted from Patwardhan et al. [76]. Satisfaction with the establishment, which addresses the overall evaluation of the customer experience, based on Hellier et al. [77]. Revisit intention, which measures customers’ intention to return to the establishment, also adapted from Hellier et al. [77]. For more information, refer to Table 3.

Table 3.

Psychometric Properties of the Constructs and Indicators Used in the Study.

3.3. Analysis

The testing of the research hypotheses was conducted in two stages. In the first stage, the measurement model was evaluated using confirmatory factor analysis (AFC) to ensure that the scales used met the criteria for reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Indicators such as Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability index (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), and the HTMT index were used for reflective indicators, while for formative indicators, the variance inflation factor (VIF) and the significance of the weights were evaluated using bootstrapping.

A reflective indicator is one in which the observed variables are manifestations of the latent construct; that is, any change in the construct will be reflected in the indicators. For example, the construct “perception of security” is manifested through various indicators that reflect the overall sense of protection and tranquility. If the perception of security improves, we would expect all its indicators to improve simultaneously, such as the tranquility when moving through the area, confidence in the environment, and the sense of protection. In contrast, a formative indicator is one in which the observed variables form the construct, so a modification in one of these indicators can change the nature of the construct. Similarly, “Lighting” is formed from independent elements. For example, the construct “Visibility” is formed by indicators such as “access visible from the public road,” “doors and windows visible from the street,” and “visible surrounding spaces,” which are distinct aspects that together create the concept of visibility, without these elements necessarily being interchangeable or highly correlated with each other.

In the second stage, a partial least squares structural equation model (PLS) was applied to test the proposed relationships. A hierarchical structure with second-order constructs (Surveillance and Access Control) was developed using the repeated indicators approach, which allowed capturing more complex relationships between the elements of crime prevention through environmental design. The analysis determined the p-values and coefficients of the paths, evaluating both the measurement models (reflective and formative) and the structural model, following the systematic procedure recommended by Hair et al. [78]. This approach made it possible to examine how the different components of the physical environment contribute to the perception of security and how this, in turn, impacts key marketing variables such as satisfaction with the establishment and revisit intention.

Additionally, to explore in detail the lack of significance in the relationship between Access Control and Perception of Security (H2), a subgroup analysis was chosen, dividing the total sample into two categories (“Restaurants” and “Bars and Nightclubs”) and running the PLS model independently for each subgroup. This approach allowed comparing the path coefficients, p-values, and t-statistics separately to determine if the effect of Access Control varied according to the type of establishment.

Below, in Table 3, the psychometric properties of the variables evaluated in the study are presented.

The results of the analysis of the psychometric properties of the measurement model reveal satisfactory performance for both reflective and formative constructs. For the reflective constructs, all showed adequate reliability values, with Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) indices above the recommended threshold of 0.70 [78]. The alpha values ranged between 0.803 (Landscaping and Revisit) and 0.945 (Satisfaction), while composite reliability showed values between 0.879 (Landscaping) and 0.960 (Satisfaction), demonstrating robust internal consistency for all reflective scales. Regarding convergent validity, the average variance extracted (AVE) for all reflective constructs exceeded the critical value of 0.50, ranging from 0.589 (Perception of Security) to 0.858 (Satisfaction), indicating that each construct explains more than 50% of the variance of its indicators [78]. Additionally, the factor loadings of most reflective items were above 0.70, with some exceptions that nevertheless exceeded the minimum acceptable threshold of 0.40 [79].

For the formative constructs, the collinearity analysis showed VIF values below 5 in all cases (with a maximum of 4.0 for Signage), indicating the absence of severe multicollinearity issues [80]. Most of the weights of the formative indicators were statistically significant (p < 0.001), confirming their unique contribution to the corresponding construct. In cases where the weights did not reach statistical significance (V2 and V5), they were retained in the model because their absolute loadings were above 0.50 (0.817 and 0.786, respectively), following the recommendations of Hair et al. [78] for the evaluation of formative indicators.

However, it is important to note that an anomaly was identified in item T5 of the Landscaping construct, which presented a substantially low factor loading (0.311), well below the minimum acceptable threshold of 0.40. This result suggests that the item does not adequately reflect the same construct as the other Landscaping indicators, which are more oriented towards the quality and maintenance of green areas rather than their quantity or proportion. Therefore, following the purification criteria recommended in the methodological literature, the decision was made to remove this item from the model to improve the validity of the Landscaping scale [79]. The second-order constructs (Surveillance, Access Control, and Territoriality) also showed adequate psychometric properties, configured as formative and evaluated using the repeated indicators approach. This hierarchical structure effectively captured the conceptual complexity of the CPTED (Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design) model and its relationship with the dependent variables of interest.

3.4. Discriminant Validity

To establish the discriminant validity of the measurement items, the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio test was applied. Below, Table 4 presents the HTMT test for the reflective constructs, from which it can be inferred that all values are below the critical threshold of 0.85, as recommended by Henseler et al. [81], with values ranging from 0.192 (Trust in the Police –Maintenance) to 0.81 (Satisfaction–Revisit). Although the latter value is relatively high, it is conceptually expected, as both constructs capture related aspects of the customer experience. The HTMT matrix includes only the six reflectively measured constructs (Trust in the Police, Maintenance, Landscaping, Perception of Security, Revisit, and Satisfaction), as this test is not applicable for assessing formative constructs or higher-order constructs with repeated indicators. Moderate relationships are also observed between Perception of Security and Satisfaction (0.70), as well as between Perception of Security and Revisit (0.74), which is consistent with the theoretical framework postulating connections between these aspects of the consumer.

Table 4.

Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) Ratio for Reflective Constructs.

4. Results

4.1. Structural Model

Once the measurement model was validated, the structural model was evaluated using PLS-SEM to examine the causal relationships between the proposed constructs. This evaluation followed the systematic procedure recommended by Hair et al. [78], which includes analyzing path coefficients (β), their statistical significance (p-values), the coefficient of determination (R2), and the effect size (f2).To establish the statistical significance of the relationships, the bootstrapping technique was applied with 5000 subsamples, allowing confidence intervals and t-values to be obtained for each structural relationship. The effect size (f2) was evaluated according to Cohen’s criteria, considering values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 as indicators of small, medium, and large effects, respectively. Below, Table 5 presents the results of the structural analysis.

Table 5.

Structural analysis model.

The results show that the model explains 47% of the variance in Perception of Security (R2 = 0.47), 43% in Satisfaction (R2 = 0.43), and 41% in Revisit (R2 = 0.41). These R2 values suggest a moderate-to-high explanatory power of the model. Regarding the determinants of Perception of Security, Surveillance shows a positive and significant relationship (β = 0.264, p < 0.001) with a low-to-moderate effect size (f2 = 0.09). Maintenance has the greatest direct effect on Perception of Security (β = 0.304, p < 0.001) with a moderate effect size (f2 = 0.10), followed by Trust in the Police (β = 0.203, p < 0.001) with a low-to-moderate effect (f2 = 0.07), and Territoriality (β = 0.184, p < 0.001) with a small effect (f2 = 0.04). On the other hand, Access Control does not show a significant relationship with Perception of Security (β = −0.010, not significant), presenting an effect size that is practically null (f2 = 0.01).

Regarding the consequences of Perception of Security, this variable exerts a positive and highly significant influence on both Satisfaction (β = 0.662, p < 0.001) and Revisit (β = 0.641, p < 0.001), with large effect sizes in both cases (f2 = 0.69 and f2 = 0.78, respectively). These results highlight the crucial role that the perception of security plays as a mediator between the elements of the physical environment and the attitudinal and behavioral responses of customers.

These findings support five of the six hypotheses proposed in the study. Specifically, it is confirmed that Surveillance, Territoriality, Maintenance, and Trust in the Police are significant determinants of Perception of Security, while the hypothesis related to Access Control is rejected. Additionally, the positive effect of Perception of Security on Satisfaction and the intention to Revisit is validated. The moderately high R2 values (between 41% and 47%) suggest that the model adequately captures the factors influencing the dependent variables studied, although there may be other variables not included that could complement the explanation of these phenomena.

4.2. Subgroup Analysis for Hypothesis H2

To further investigate the non-significance of hypothesis H2—that is, the relationship between Access Control and Perception of Security—a subgroup analysis was conducted by dividing the sample between customers of “Restaurants” and “Bars and Nightclubs.” The results presented in Table 6 indicate that the relationship was not statistically significant in either context. For the Restaurant group, the effect was practically null and non-significant (β = −0.010, p = 0.807). Similarly, for the Bars and Nightclubs group, the relationship was also not statistically significant (β = −0.010, p = 0.794). These findings suggest that the lack of an effect in the overall model is not due to differences between the groups but rather reflects a consistent absence of this relationship in the studied sample.

Table 6.

Results of the Subgroup Analysis.

4.3. Structural Model Evaluation

In accordance with the recommendations of Hair et al. [78], a bootstrapping procedure with 500 iterations was employed to estimate the statistical significance of the indicator weights and the model’s relationship coefficients. The R2 was calculated for the endogenous constructs as a diagnostic tool to evaluate the explanatory power of the model. The overall goodness-of-fit measure (GoF) was calculated by combining two key components: first, the geometric mean of the communality (AVE) of the reflective constructs, which measures the amount of variance that the indicators share with their latent construct; and second, the average R2 for the endogenous dependent constructs, which reflects the proportion of variance explained by the predictors in the model. Subsequently, the GoF was estimated using the square root of the product of these values.

According to established criteria, GoF values are categorized as low (0.10), medium (0.25), and high (0.36). In this study, the obtained GoF of 0.570 suggests an outstanding fit, far exceeding the threshold for a high level, which reflects a great explanatory capacity of the model (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Model Evaluation.

To evaluate the predictive relevance of the model, the Stone-Geisser Q2 index was used through a blindfolding procedure [82]. The Q2 calculation results for the three endogenous constructs (Perception of Security, Satisfaction, and Revisit) greatly exceeded the threshold of zero (0.267, 0.369, and 0.290, respectively), which evidences substantial predictive relevance. In summary, the model explains 47% of the variance in Perception of Security, 43% in Satisfaction, and 41% in Revisit Intention, values that can be considered moderate to high for research in social sciences.

According to Chin [83], R2 values of 0.19, 0.33, and 0.67 can be interpreted as weak, moderate, and substantial, respectively, in the context of PLS-SEM. Similarly, Hair, Hult, Ringle, and Sarstedt [78] argue that in behavioral studies, R2 values around 0.25 can already be considered acceptable. The high GoF value (0.570) and robust Q2 indicators confirm that the model has considerable explanatory and predictive capacity for the relationships between elements of the physical environment, perception of security, and their consequences on consumer behavior.

5. Discussion

The results obtained confirm the relevance of both CPTED principles and institutional aspects in shaping the perception of security in nighttime establishments, and how this perception significantly influences key marketing variables such as satisfaction and revisit intention. The proposed integrated model, which combines physical-environmental elements with trust in the Police, demonstrates robust explanatory power.

The finding that maintenance is the most potent predictor of the perception of security (β = 0.304) reinforces the Broken Windows Theory [67] and aligns with studies such as that of Salem et al. [69], who found that well-maintained spaces generate greater trust and perception of control. This result underscores the critical importance that consumers place on visual signals of care and attention in assessing perceived risk.

Surveillance, for its part, emerges as the second most important predictor (β = 0.264), confirming its fundamental role in reducing uncertainty and perceived negative consequences, as suggested by the Two-Component Basic Model [41]. These results are consistent with the findings of Kajalo and Lindblom [56], who identified surveillance as a crucial element in the formation of security perceptions in commercial environments. Territoriality, although with a more modest effect (β = 0.184), also contributes significantly to the perception of security, supporting Reynald’s [65] findings on the importance of territorial markers in communicating ownership and control of space.

An interesting finding of this study is the consistent lack of a relationship between Access Control and Perception of Security, which persisted even when analyzing the subgroups of “Restaurants” and “Bars and Nightclubs” separately. Contrary to the expectation that visible security measures would be more valued in environments of higher perceived risk such as bars and nightclubs, our data do not support this idea [63,64]. This discrepancy could be explained by the particularities of the Latin American context and the nighttime entertainment sector, where excessive physical barriers might be interpreted as indicators of danger in the area, generating a paradoxical effect. Another possible explanation is that, in nighttime leisure establishments, accessibility and openness are valued aspects that could conflict with restrictive access control measures, neutralizing their positive effect on the perception of security.

The confirmation of the positive effect of Trust in the Police on the perception of security (β = 0.203) complements the traditional CPTED model and incorporates the institutional component, highlighting that perceived security does not depend exclusively on physical design, but also on the broader social and institutional context, as suggested by Park et al. [70] and Kajalo et al. [56]. This finding is particularly relevant in the Latin American context, where institutional trust is often variable and problematic.

Finally, the strong effects of the perception of security on satisfaction (β = 0.662) and revisit intention (β = 0.641) highlight the crucial role of this variable as a mediator between elements of the physical environment and consumer responses. These results confirm what was proposed by Lucia-Palacios et al. [72] and Elmashhara and Soares [84] about how the reduction of perceived risk improves the customer experience and fosters positive attitudes towards the establishment. The fact that the model explains substantial proportions of the variance in the three dependent variables (47% in perception of security, 43% in satisfaction, and 41% in revisit intention) underscores the robustness of the proposed integrated approach and its potential to better understand the interaction between environmental design, perceived security, and consumer behavior in nighttime entertainment contexts.

6. Conclusions

This research has evidenced the complex interrelation between the elements of environmental design, the perception of security, and commercial outcome variables in nightlife establishments. The findings reveal that maintenance, surveillance, territoriality, and trust in the Police significantly contribute to the formation of security perceptions, while these perceptions decisively influence customer satisfaction and their intention to revisit.

From a practical perspective, these results provide valuable guidelines for owners and managers of nightlife establishments. Firstly, they suggest that investing in the proper maintenance of facilities and facades constitutes a priority strategy to improve the perception of security among customers. This aspect, relatively less costly than sophisticated technological implementations, can generate significant returns in terms of satisfaction and loyalty. Similarly, attention to surveillance elements, particularly adequate lighting and visibility from and to the exterior, emerges as a high-impact intervention that should be prioritized in the management of these spaces.

For local authorities and urban planners, these findings underscore the importance of integrating CPTED principles into urban development and construction regulations, particularly in areas with a concentration of nightlife establishments. Likewise, the significant effect of Trust in the Police on the perception of security indicates that the development of outreach programs between security forces and commercial establishments could have indirect positive effects on the economic dynamism of these areas.

However, this study presents limitations that must be considered. The use of non-probabilistic sampling in a specific city in Colombia limits the generalization of the results to other cultural and urban contexts. Although the study included various types of nightlife establishments, differences between categories (bars, restaurants, nightclubs) were not analyzed separately. Future research could address these limitations through comparative studies between different cultural and socioeconomic contexts to determine the universality of the identified relationships. Another promising line would be the exploration of possible moderating effects of variables such as the socioeconomic level of the clientele, age, gender, or previous experiences with insecurity situations.

Finally, the unexpected finding about the lack of a significant relationship between access control and the perception of security deserves particular attention in future research, exploring possible non-linear effects or those conditioned by the cultural context. This type of counterintuitive findings evidences the complexity of the perception of security as a psychosocial phenomenon and reinforces the need for interdisciplinary approaches that integrate perspectives from environmental design, criminology, marketing, and consumer psychology to better understand this multifaceted phenomenon.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.O.-A.; Data curation, C.O.-A.; Formal analysis, A.Z.-C.; Funding acquisition, C.A.-P.; Investigation, A.Z.-C.; Methodology, C.O.-A.; Project administration, C.A.-P.; Resources, A.Z.-C.; Software, C.O.-A.; Supervision, C.A.-P.; Validation, A.Z.-C.; Visualization, A.Z.-C.; Writing—original draft, C.O.-A.; Writing—review and editing, C.A.-P. and A.Z.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was conducted within the framework of the project “Digital e-commerce ecosystem for biosecure economic revival-ECOMMERCE-19”, funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology. The funding number is 2022-0797.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Accounting and Administration (Ética de la Investigación FCA–CEICA) under approval code 14 on 2 June 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants involved in this study voluntarily agreed to complete the survey after being informed of its purpose. The research was classified as minimal risk in accordance with current ethical regulations in Colombia, specifically Resolution 8430 of 1993 from the Ministry of Health, Chapter I, Article 11. No personal data from the surveyed individuals was collected or disclosed. Therefore, the study posed no risk to participants’ identity or integrity. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in ZENODO at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15566226, reference number 15566226.

Acknowledgments

In the creation of this article, Anthropic’s Claude 3.7 Sonnet generative artificial intelligence was used to support the translation of the manuscript content from Spanish to English.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questionnaire Likert Scale Questions.

Table A1.

Questionnaire Likert Scale Questions.

| Question | 1 (Totally in Disagreement) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (Totally in Agreement) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SURVEILLANCE | Visibility | |||||

| Access to the establishment is visible from the public road | ||||||

| The doors and windows of the establishment’s facade are completely visible from the street | ||||||

| The vegetation, such as trees or gardens, is kept at a height that does not obstruct the visibility of the establishment from the street | ||||||

| Illumination | ||||||

| The lighting at the entrance of the establishment is: | ||||||

| The surrounding lighting of the establishment is: | ||||||

| The public lighting in the block of the establishment is: | ||||||

| TERRITORIALITY | Maintenance | |||||

| The condition of the exterior walls of the establishment is adequate. | ||||||

| The condition of the doors and entrance of the establishment is appropriate. | ||||||

| The condition of the windows and/or display windows of the establishment is adequate. | ||||||

| The roof of the establishment is in good condition. | ||||||

| The exterior grilles, walls, or fences of the establishment are in good condition. | ||||||

| The establishment does not show acts of vandalism such as graffiti, broken glass, or debris | ||||||

| The general appearance of the facade of the establishment is adequate | ||||||

| Trust in the Police | ||||||

| I believe that the police have done a good job patrolling the area | ||||||

| I believe that the police would arrive quickly if an incident occurred in an establishment in this area | ||||||

| I trust that the police would take effective measures if a crime were reported in an establishment in this area | ||||||

| I think the police are effective in preventing crime | ||||||

| I think the police are effective in maintaining order in the public space. | ||||||

| Perception of Security | ||||||

| I feel safe when I am inside this establishment | ||||||

| I feel safe when entering and leaving the establishment | ||||||

| I feel safe walking around during the day in the area where this establishment is located | ||||||

| I feel safe walking around at night in the area where this establishment is located | ||||||

| This establishment seems safer to me than other nightlife venues in the area | ||||||

| The type of people who visit this establishment is a safe crowd | ||||||

| Satisfaction | ||||||

| My decision to visit this establishment was well made | ||||||

| I am glad to have visited this establishment | ||||||

| I am happy with the time spent in this establishment | ||||||

| I would positively recommend this nighttime establishment to others | ||||||

| Revisit | ||||||

| I will surely visit this establishment in the future | ||||||

| Even if this establishment were a bit more expensive, I would still prefer to come here | ||||||

| I have the intention to maintain a long-term relationship as a client of this establishment |

Table A2.

Questionnaire Dichotomic/Open-Ended Questions.

Table A2.

Questionnaire Dichotomic/Open-Ended Questions.

| ACCESS CONTROL | Physical Barriers | Yes | No |

| Does the establishment have some type of physical protection such as a wall, grill, or fence? | |||

| In addition to the mentioned protection before, is there any other visible security element of the place? | |||

| Security Systems | |||

| How many security elements such as surveillance cameras, alarms, or others are observed in the establishment? | Whole number | ||

| TERRITORIALITY | Signage | ||

| Does the establishment have any sign that indicates it is private property or restricted access? | |||

| Landscaping | |||

| The general aspect of the green areas and the exterior decoration is excellent | |||

| There are decorative elements or well-maintained plants at the entrance of the place | |||

| The green areas and exterior decoration of the establishment are kept in good condition | |||

| The proportion of green areas compared to the built surface of the establishment is elevated | |||

References

- Simittchiev, R. Nightclub Security Strategy in Finland. Master’s Thesis, Laurea University of Applied Sciences, Vantaa, Finland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.S.; Park, S.; Jung, S. Effect of crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED) measures on active living and fear of crime. Sustainability 2016, 8, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.Y.; Lee, K.H. Effects of changes in neighbourhood environment due to the CPTED project on residents’ social activities and sense of community. Int. J. Urban. Sci. 2017, 21, 326–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, M.; Gatica, F.; Cartes, I.; Pascoe, T.; Carrasco, V. Perception of criminal insecurity in vulnerable districts Latin America. Urban Reg. Plan. 2019, 4, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornemann, N. Safety in the Nighttime Economy. What Factors Influence the Subjective Perception of Safety in the Nighttime Economy Based on Sample Locations in Berlin? Geographisches Institut, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 2023; Heft 207, ISSN 0947-0360; Available online: https://www.geographie.hu-berlin.de/de/institut/publikationsreihen/arbeitsberichte/download/arbeitsberichte_207_migrants_and_their_economic_activities_berlin_2023.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Peng, Y.L.; Li, Y.; Cheng, W.Y.; Wang, K. Evaluation and Optimization of Sense of Security during the Day and Night in Campus Public Spaces Based on Physical Environment and Psychological Perception. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghari Zamani, A.; Roostaei, S.; Zali, N.; Shafiee-Masuleh, S.S. Investigating the Pivotal Role of Space-Time Flow of Sunset and Night Activities in the Perception of Security: A Case Study of Rasht City Center. Motaleate Shahri 2021, 10, 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Philpot, R.; Liebst, L.S.; Møller, K.K.; Lindegaard, M.R.; Levine, M. Capturing violence in the night-time economy: A review of established and emerging methodologies. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2019, 46, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuong, N.T. Developing night-time economy: International experience and policy implications for Da Nang City, Vietnam. J. Lang. Linguist. Stud. 2022, 18, 1157–1180. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, V.S.; Qin, Y.; Ying, T.; Shen, S.; Lyu, G. Night-time economy vitality index: Framework and evidence. Tour. Econ. 2022, 28, 665–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songole, H.S. A systematic review of the CPTED–quality of life relationship. Safer Communities 2024, 23, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzbali, M.H.; Abdullah, A.; Ignatius, J.; Tilaki, M.J.M. Examining the effects of crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED) on Residential Burglary. Int. J. Law Crime Justice 2016, 46, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Kang, S. Assessing Surveillance and Access Control Factors Impacting Burglary in Multi-Family Housing From a CPTED Perspective. J. Archit. Inst. Korea 2025, 41, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, H.; Matsumoto, Y.; Yamagishi, H.; Yamamoto, T.; Kashihara, S.; Minobe, K. Development of the models showing the extent of natural surveillance by using light projecting method. AIJ J. Technol. Des. 2008, 14, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yamamoto, T.; Matsumoto, Y.; Kashihara, S.; Ogushi, A. Research on burglary risk of houses affected by usage of surrounding lots and the streets. AIJ J. Technol. Des. 2007, 13, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Curtis-Ham, S.J.; Cantal, C.B. Locks, Lights, and Lines of Sight: An RCT Evaluating the Impact of a CPTED Intervention on Repeat Burglary Victimisation. J. Exp. Criminol. 2023, 19, 397–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J. The (In)Effectiveness of Campus Smart Locks for Reducing Crime. J. Appl. Secur. Res. 2023, 18, 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, C. Alley-gates and domestic burglary: Findings from a longitudinal study in urban South Wales. Police J. 2018, 91, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senna, I.; Iglesias, F.; Matsunaga, L.H.; da Silva, C.M. Territoriality and fear of crime: Conceptual issues and methodological challenges in crime prevention. Estud. Psicol. 2021, 26, 424–433. Available online: https://submission-pepsic.scielo.br/index.php/epsic/article/view/21829/1031 (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Ha, T.; Oh, G.; Park, H. Comparative Analysis of Defensible Space in CPTED Housing and Non-CPTED Housing. Int. J. Law Crime Justice 2015, 43, 496–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Lee, K. A Study on the Physical Factors Causing Fear of Crime in Public Spaces in Multi-Family Housing-Focusing on the Semi-private Space of the Apartment Complex. J. Archit. Inst. Korea 2024, 40, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, R.N.; O’Boyle, M.W. Graffiti and perceived neighborhood safety: A neuroimaging study. Prop. Manag. 2019, 37, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozens, P.M.; Tarca, M. Exploring Housing Maintenance and Vacancy in Western Australia: Perceptions of Crime and Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED). Prop. Manag. 2016, 34, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valasik, M.A.; Brault, E.E.M.; Martinez, S.M. Forecasting homicide in the red stick: Risk terrain modeling and the spatial influence of urban blight on lethal violence in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Soc. Sci. Res. 2019, 80, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.B.; Hedayati Marzbali, M.; Maghsoodi Tilaki, M.J. Predicting the Influence of CPTED on Perceived Neighbourhood Cohesion: Considering Differences across Age. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakip, S.R.M.; Rahim, P.R.M.A.; Nayan, N.M. Establishing Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design Model. Int. J. Sustain. Constr. Eng. Technol. 2023, 14, 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senna, I.; Iglesias, F.; Matsunaga, L.H. Measuring the effects of Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) on fear of crime in public spaces. Crime Prev. Community Saf. 2025, 27, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Hino, K.; Asami, Y.; Usui, H.; Nakajima, M. Fear of Street Crime among Japanese Mothers with Elementary School Children: A Questionnaire Survey Using Street Montage Photographs. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 23, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, J. Discussion on defense safety design of typical semi-gated residential community in Changchun in view of weakening fear of crime. J. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. 2020, 52, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauregui, C.; Trinidad, A.; Vozmediano, L. Women’s Safety Perception Before and After the Reconstruction of an Urban Area: A Mixed-Method Research. Violence Against Women 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-Y.; Han, G.; Rhee, J.-H.; Lee, K. Gender disparities in perceived visibility and crime anxiety in piloti parking spaces of multifamily housing: A virtual reali-ty study. Front. Archit. Res. 2025, 14, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Kumari, R. Towards gender-inclusive cities: Prioritizing safety parameters for sustainable urban development through multi-criteria decision analysis. Int. J. Sustain. Build. Technol. Urban Dev. 2023, 14, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, L.A.; Bhatia, S.; Lee, D.B.; Wyatt, R.; Bushman, G.; Wyatt, T.A.; Pizarro, J.M.; Wixom, C.R.; Zimmerman, M.A.; Reischl, T.M. Community-engaged crime prevention through environmental design and reductions in violent and firearm crime. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2025, 76, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupp, L.A.; Zimmerman, M.A.; Sly, K.W.; Reischl, T.M.; Thulin, E.J.; Wyatt, T.A.; Stock, J.P. Community-Engaged Neighborhood Revitalization and Empowerment: Busy Streets Theory in Action. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2020, 65, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz Montemayor, G. Recovering Subsidized Housing Developments in Northern México: The Critical Role of Public Space in Community Building in the Context of a Crime and Violence Crisis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Park, J. Illuminating Safety: The Impact of Street Lighting on Reducing Fear of Crime in a Virtual Environment. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 12464–12478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-h.; Hwang, T.; Kim, G. The Role and Criteria of Advanced Street Lighting to Enhance Urban Safety in South Korea. Buildings 2024, 14, 2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R. Pedestrian post-twilight illuminance levels for security, visual comfort, and related parameters. Cities Health 2024, 8, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Mahdzar, S.S.S.; Khaidzir, K.A.M. Examining the urban morphology and defensive mechanisms of Dutch Malacca via topology, space syntax, and sDNA under the framework of CPTED theory. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safizadeh, M.; Hedayati Marzbali, M.; Abdullah, A.B.; Maghsoodi, M.J. Integrating space syntax and CPTED in assessing outdoor physical activity. Geogr. Res. 2024, 62, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, S.M. The Major Dimensions of Perceived Risk. In Risk Taking and Information Handling in Consumer Behavior; Cox, D.F., Ed.; Harvard University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1967; pp. 82–108. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, W.; Na, J.; Lee, S. Assessment of Residents for CPTED-Based Crime Prevention Services in South Korea. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2025, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan Abdullah, O.A.; Mohd Mahdee, J.; Mohd Fauzi, N. The Influence of Service Marketing Mix on Customer Loyalty Towards Travel Agents Post Covid-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Manag. Financ. Account. 2025, 6, 243–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, G.; Weinstein, J.M.; Christia, F.; Arias, E.; Badran, E.; Blair, R.A.; Wilke, A.M. Community Policing Does Not Build Citizen Trust in Police or Reduce Crime in the Global South. Science 2021, 374, eabd3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.E.; Capellan, J.; Barthuly, B. Trust in the police and the militarization of law enforcement in Latin America. In Comparing Police Organizations; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2024; pp. 56–85. [Google Scholar]

- Dzordzormenyoh, M.K. Residential Types, Neighborhood Security and Public Trust in Ghana Police Service: A Comprehensive Analysis. Policing Int. J. 2025, 48, 284–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saáry, R.; Csiszárik-Kocsir, Á.; Varga, J. Examination of the Consumers’ Expectations Regarding Company’s Contribution to Ontological Security. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolins, R. Nightclubs, Restaurants, and Bars. In Hospitality Security; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 297–355. [Google Scholar]

- Ramello, R. The Impact of Night-Time Economy Districts on Violence and Perception of Safety at Night. Ph.D. Thesis, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, F.; Liu, Y.; Chang, Y.; Duan, J.; Li, J. An Overview of Tourism Risk Perception. Nat. Hazards 2016, 82, 643–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Hou, Y. The effect of perceived risk on information search for innovative products and services. J. Consum. Mark. 2017, 34, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Marzbali, M.H. How Urban Park Features Impact Perceived Safety by Considering the Role of Time Spent in the Park, Gender, and Parental Status. Cities 2024, 153, 105272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, M.J.; Jacomo, A.L.; Armenise, E.; Brown, M.R.; Bunce, J.T.; Cameron, G.J.; Fang, Z.; Farkas, K.; Gilpin, D.F.; Graham, D.W.; et al. Understanding and managing uncertainty and variability for wastewater monitoring beyond the pandemic: Lessons learned from the United Kingdom national COVID-19 surveillance programmes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sas, M.; Snaphaan, T.; Pauwels, L.J.; Ponnet, K.; Hardyns, W. Using systematic social observations to measure crime prevention through environmental design and disorder: In-situ observations, photographs, and google street view imagery. Field Methods 2023, 35, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monchuk, L.; Clancey, G. What Police Say About Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED) Training in Two Jurisdictions (England/Wales and New South Wales, Australia). Polic. A J. Policy Pract. 2021, 15, 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajalo, S.; Lindblom, A. The role of formal and informal surveillance in creating a safe and entertaining retail environment. Facilities 2016, 34, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensdotter, A.O.N.; Guaralda, M. Dangerous safety or safely dangerous: Perception of safety and self-awareness in public space. J. Public Space 2018, 3, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajalo, S.; Lindblom, A. Effectiveness of formal and informal surveillance in reducing crime at grocery stores. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2011, 18, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, A.; Barbieri, N.; Rodriquez, J. Do Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design Strategies Deter Taggers? Voices from the Street. Qual. Criminol. 2021, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.; Mohd Salleh, M.N.; Sakip, S.R.M. Fear of Crime in Residential Areas. Asian J. Environ. Behav. Stud. 2013, 4, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- He, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Chan, S.; Cheng, Y.; Guizani, N. Vulnerability Analysis and Security Compliance Testing for Networked Surveillance Cameras. IEEE Netw. 2020, 34, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, D.; Amemiya, M.; Shimada, T. What do security cameras provide for society? The influence of cameras in public spaces in Japan on perceived neighborhood cohesion and trust. J. Exp. Criminol. 2020, 18, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, R.; Joyce, C.; Monchuk, L. Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED) and Retail Crime: Exploring Offender Perspectives on Risk and Protective Factors in the Design and Layout of Retail Environments. In Retail Crime: International Evidence and Prevention; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 123–154. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, N.; Jung, H. Surveillance robot as a supplementary tool for crime prevention through environmental design: Using Q methodology for analyzing perceptions of police officers in Busan. Korean Assoc. Public Saf. Crim. Justice 2023, 32, 31–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynald, D. Translating CPTED into Crime Preventive Action: A Critical Examination of CPTED as a Tool for Active. Eur. J. Crim. Policy Res. 2011, 17, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajalo, S.; Lindblom, A. Surveillance investments in store environment and sense of security. Facilities 2010, 28, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.Q.; Kelling, G.L. Broken windows. In Critical Issues in Policing: Contemporary Readings; Dunham, R.G., Alpert, G.P., Eds.; Waveland Press Inc.: Prospect Heights, IL, USA, 1989; p. 530. [Google Scholar]

- Lanfear, C.; Matsueda, R.; Beach, L. Broken Windows, Informal Social Control, and Crime: Assessing Causality in Empirical Studies. Annu. Rev. Criminol. 2020, 3, 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, I.E.; Elkhwesky, Z.; Baber, H.; Radwan, M. Hotel resuscitation by reward-based crowdfunding: A critical review and moderated mediation model. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 43, 100986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lu, H.; Donnelly, J.; Hong, Y. Untangling the Complex Pathways to Confidence in the Police in South Korea: A Stepwise Multilevel Structural Equation Modeling Analysis. Asian J. Criminol. 2021, 16, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddell, R.; Trott, K. Perceptions of trust in the police: A cross-national comparison. Int. J. Comp. Appl. Crim. Justice 2022, 47, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia-Palacios, L.; Pérez-López, R.; Polo-Redondo, Y. Does stress matter in mall experience and customer satisfaction? J. Serv. Mark. 2020, 34, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, T.T.N.; Thang, P.C.; Quy, T.Q. Examining the Influence of Security Perception on Customer Satisfaction: A Quantitative Survey in Vietnam. EAI Endorsed Trans. Internet Things 2024, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šerić, N.; Stojanović, A.J.; Bagarić, L. The influence of the security perception of a tourist destination on its competitiveness and attractiveness. Proc. Fac. Econ. East Sarajevo 2022, 24, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Hwang, E. Confidence in the police among Korean people: An expressive model versus an instrumental model. Int. J. Law Crime Justice 2014, 42, 306–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwardhan, V.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Payini, V.; Woosnam, K.M.; Mallya, J.; Gopalakrishnan, P. Visitors’ place attachment and destination loyalty: Examining the roles of emotional solidarity and perceived safety. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellier, P.K.; Geursen, G.M.; Carr, R.A.; Rickard, J.A. Customer Repurchase Intention: A General Structural Equation Model. Eur. J. Mark. 2003, 37, 1762–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Phabmixay, C.S. Gestión Empresarial del Sistema de Reclamaciones y Quejas Bajo los Enfoques Mecanicista y Orgánico: Antecedentes y Resultados. 2015. Available online: http://uvadoc.uva.es/handle/10324/16798 (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Thiele, K.O. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Peterson, R.A.; Brown, S.P. Structural Equation Modeling in Marketing: Some Practical Reminders. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2008, 16, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The Partial Least Squares Approach to Structural Equation Modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Elmashhara, M.; Soares, A. Leveraging Consumer Chronic Time Pressure and Time Management to Improve Retail Venue Outcomes. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2024, 17, 484–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).