Method and Practice for Integrated Water Landscapes Management: River Contracts for Resilient Territories and Communities Facing Climate Change

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Water Landscapes: A Shared Framework to Face Climate Change

1.2. River Contracts: An Innovative, Voluntary Practice for Water Landscapes’ Regeneration

1.3. River, Lake, Coastal and Lanscape Contracts: A Resilient and Multi-Level Governance Method

- Horizontal and vertical subsidiarity;

- Participatory local development;

- Sustainability.

- Phase 1: Document of Intent (Manifesto). The vision and general objectives, with reference to the Directive 2000/60/EC (Art. 4), point out the specific critical issues and the working methodology, shared among the actors taking part in the process.

- Phase 2: Integrated Knowledge Analysis. The environmental, social, economic and cultural values of the territory.

- Phase 3: Strategic Plan. The scenario, referred to as a medium-long-term time horizon, that integrates the objectives of local and territorial planning.

- Phase 4: Action Program (AP). To define the time horizon (from three to five years) of the activities and update the contract with the approval of a new AP.

- Phase 5: Participatory Processes. To enable the sharing of intentions, commitments and responsibilities among the stakeholders.

- Phase 6: Formal Agreement. To define the decisions shared in the participatory process and the specific commitments of the contractors.

- Phase 7: Periodic Monitoring System. To check the status of implementation of the various phases and actions, the quality of participation and the resulting deliberative processes.

- Phase 8: Public Information. Accessibility to data and information on the River Contract.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. River Contracts in the Lazio Region: An Ongoing Research Study

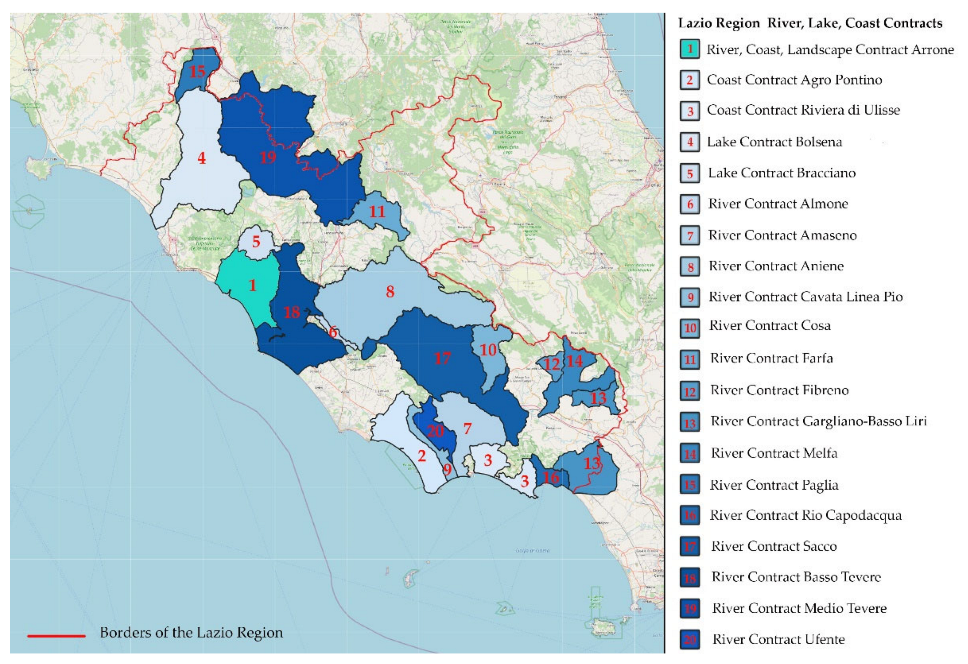

2.2. The Lazio Region River Contracts a Recent Field of Experimentation

2.3. The Contextualisation of the Case Study

2.4. The River, Coastal, Landscape Contract Arrone

3. Results

- Phase 1: Document of Intent. The general objectives of the contract, divided into the five assets (landscape and nature, water, quality agriculture, technology and active citizens and enhancement—Cfr. Par. 2.4 and Table 3) with the consequent definition of activities and initiatives, which combine long-term strategies and short-term actions, supported by top-down institutional policies and bottom-up initiatives (Table 4), result in increasing awareness of territorial values and heritage. The local community was called upon to develop a shared vision by bringing out conflicts, interests and territorial vocations through the definition of the thematic tables, which has contributed to the initiation of a participatory process, which is necessary for the reappropriation of responsibility in the management of water resources. The exhaustive identification of problems and actions expressed in Phase 1: Document of Intent is fundamental for achieving concrete and lasting results in terms of territorial, social and environmental resilience.

- Phase 2: Integrated Knowledge Analysis. This phase, organized around water and landscape and their management as resources, has helped the community recognize the identity of places as a driver for innovation and sustainable change. The thematic tables have seen an increasing level of population involvement on specific issues in their territory, enhancing the rural vocation and the coastal landscape. The four tables on Agro-food, the Coast, Water and Tourism have succeeded in promoting a dialogue between citizens and stakeholders, giving back knowledge of risk and a sense of community. The specific initiatives have demonstrated a wide participation of the communities in the process, in particular the involvement of local educational institutes [48]. The need for empowerment of the youngest through participation in the discovery of the territory has seen the local schools involved in the project “Amarcord” focus, in particular, on the figure of Salvo D’Aquisto, building a network of 28 schools in Italy dedicated to the Italian hero of World War II (Table 4). Knowledge means a profound understanding of local landscapes and cultural values that correspond to new forms of territorial, social and ecological resilience.

- Phase 3: Strategic Document. The multi-level governance approach and the use of “systemic forces”, promoters and stakeholders (e.g., research units, schools, associations) represent evidence of improving coherent and quality objectives and interventions as well as strengthening sustainable activities at the basis of local economies. The Strategic Matrix developed within the Strategic Document ensures the coherence between the contract and the implementation and coordination of safeguarding and promotion plans and programs already in force in the area (Regional Landscape Territorial Plan-PTPR; Provincial General Territorial Plan-PTPG; General Regulatory Plan-PRG; Management Plan of the Natural Reserve Litorale Romano, Directive 92/43/EEC, Framework Directive 2000/60/EC, Directive 2007/60/EC, Framework Directive 2008/56/EC).

- Phase 4: Action Program (AP) The Action Program has set up all the specific interventions aimed at implementing multi-scalar and multi-sectors projects related to integrate water management with a quality approach to river safety, valorization of agricultural productivity, social and economic development, sustainable mobility systems, blue and green infrastructure, nature-based solutions, ecological place-based interventions (Table 5).

- Phase 5: Participatory processes. The sharing of intentions, commitments and responsibilities among authorities, citizens and stakeholders (Table 5) referred to the specific actions of Phase 4 has enabled the definition of the initiatives aimed at improving social involvement and increasing awareness of local identity.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Discussion

4.2. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ICWE. The Dublin Statement on Water and Sustainable Development. International Conference on Water and the Environment, Dublin. 1992. Available online: https://www.gdrc.org/uem/water/dublin-statement.html (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- UN. Conference on Environment and Development. Rio Declaration on Environment and Development 14 June 1992. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/conferences/environment/rio1992 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Charter of European Cities and Towns: Towards Sustainability (the Aalborg Charter). European Sustainable Cities & Towns Campaign. 1994. Available online: https://sustainablecities.eu/the-aalborg-charter/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- EU. Water Framework Directive (WFD) 2000/60/EC. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/water/water-framework/index_en.html (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- EP. Directive 2007/60/EC. Assessment and Management on Flood Risk. 2007. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32007L0060 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- EEA. The European Environment—State and Outlook 2010. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/soer/2010/synthesis/synthesis (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- EEA. Climate Change, Impacts and Vulnerability in Europe 2012. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/climate-impacts-and-vulnerability-2012 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- EEA. Climate Change, Impacts and Vulnerability in Europe 2016. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu//publications/climate-change-impacts-and-vulnerability-2016 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- EC. Habitats Directive 92/42/EEC. Conservation of Natural and Semi-natural Habitats and of Wild Fauna and Flora. 1992. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/legislation/habitatsdirective/index_en.htm (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- EU. The Urban Agenda for the EU. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/policy/themes/urbandevelopment/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Mostafavi, M.; Doherty, G. Ecological Urbanism; Lars Muller: Baden, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- UN. New Urban Agenda 2017. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/policy/themes/urban-development/new-urban-agenda (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- EU. A European Green Deal. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- EC. Biodiversity Strategy for 2030. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/biodiversity-strategy-2030_en (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Bastiani, M. Dalla valorizzazione degli ambiti fluviali ai contratti di fiume. In Contratti di Fiume. Pianificazione Strategica e Partecipata dei bacini Idrografici. Approcci, Esperienze, casi Studio; Bastiani, M., Ed.; Flaccovio Editore: Palermo, Italy, 2011; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tavolo Nazionale dei Contratti di Fiume. Carta Nazionale dei Contratti di Fiume. Available online: http://www.a21italy.it/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/CARTA_CONTRATTI_DI_FIUME_2010.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- WWC. From Vision to Action. 2000. Available online: https://www.worldwatercouncil.org/sites/default/files/World_Water_Forum_02/The_Hague_Declaration.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Jønch-Clausen, T.; Fugl, J. Firming up the Conceptual Basis of Integrated Water Resources Management. Water Res. Develop. 2001, 17, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleurbaey, M.; Kartha, S.; Bolwig, S.; Chee, Y.L.; Chen, Y.; Corbera, E.; Lecocq, F.; Lutz, W.; Muylaert, M.S.; Norgaard, R.B.; et al. Sustainable Development and Equity. In Climate Change. Mitigation of Climate Change; Edenhofer, O., Pichs-Madruga, R., Sokona, Y., Farahani, E., Kadner, S., Seyboth, K., Adler, A., Baum, I., Brunner, S., Eickemeier, P., et al., Eds.; Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/ipcc_wg3_ar5_chapter4.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Brun, A. France’s Water Policy: The Interest and Limits of River Contracts. In Globalized Water. A Question of Governance; Schneier-Madanes, G., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 139–147. [Google Scholar]

- UNCD. The Future We Want. 2012. Available online: https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/66/288&Lang=E (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Scaduto, M.L. Theoretics and Methodology. In River Contracts and Integrated Water Management in Europe; UNIPA Springer Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- MITE. Strategia Nazionale di Adattamento ai Cambiamenti Climatici. 2013. Available online: https://www.mite.gov.it/sites/default/files/archivio/allegati/clima/documento_SNAC.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. IPCC Sixth Assessment Report. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Italian National Board on River Contracts. A bottom-Up Innovative Approach to Enhance the Participatory Governance of River Basin. Available online: https://www.italywaterforum.it/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/River-Contracts-in-Italy.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- UN-Water. Integrated Water Resources Management. Available online: https://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/iwrm.shtml (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Tavolo Nazionale dei Contratti di Fiume. Definizioni e Requisiti Qualitativi di base dei Contratti di Fiume. Available online: http://www.a21fiumi.eu/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=lWIa1b8MdEs%3d&tabid=36&mid=374 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Davoudi, S.; Shaw, K.; Haider, L.J.; Quinlan, A.E.; Peterson, G.D.; Wilkinson, K.; Fünfgeld, H.; McEvoy, D.; Porter, L. Resilience: A Bridging Concept or a Dead End? “Reframing” Resilience: Challenges for Planning Theory and Practice. Interacting Traps: Resilience Assessment of a Pasture Management System in Northern Afghanistan. Urban Resilience: What Does it Mean in Planning Practice? Resilience as a Useful Concept for Climate Change Adaptation? The Politics of Resilience for Planning: A Cautionary Note. Plan. Theory Pract. 2012, 13, 299–333. [Google Scholar]

- Voghera, A. Regional planning for linking parks and landscape: Innovative issues. In Nature Policies and Landscape Policies towards an Alliance; Gambino, R., Peano, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Voghera, A. Un patrimonio “minore”. Capitale fisso sociale e ricostruzione di contesti territoriali. In Archivio Di Studi Urbani E Regionali; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2017; pp. 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Voghera, A.; Giudice, B. Evaluating and planning green infrastructure: A strategic perspective for sustainability and resilience. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regione Lazio. Atlante Degli Obiettivi per la Diffusione dei Contratti di Fiume, di Lago, di Costa e di Foce. Available online: https://progetti.regione.lazio.it/contrattidifiume/atlante-dei-cdf/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Rossi, F. Servizi ecosistemici e nuovo welfare. Prospettive di rigenerazione per il litorale romano, Ananke 2020, 91, 137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, F.; Cantaro, A. Coast-amination. Regeneration paths between water and land along the Lazio southern coast. In WORLD HERITAGE and CONTAMINATION; Le Vie dei Mercanti; Gambardella, C., Ed.; Gangemi Editore: Rome, Italy, 2020; Volume 6, pp. 596–605. [Google Scholar]

- Sereni, E. Storia del Paesaggio agrario italiano; Laterza: Bari, Italy, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Lattanzi, G. Il risanamento idraulico. In Fiumicino tra cielo e mare; Publidea 95: Ostia Antica, Rome, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Iacomoni, A.; Rossi, F. Sistemi insediativi policentrici e territorio rurale. Le strategie per il recupero delle relazioni fra ambiente urbano e rete dei servizi ecosistemici. In Le nuove Comunità Urbane e il Valore Strategico della Conoscenza; Talia, M., Ed.; Planum Publisher: Roma-Milano, Italy, 2020; pp. 168–174. [Google Scholar]

- Regione Lazio. Adozione del Piano di gestione e del regolamentoattuativo della Riserva Naturale Statale Litorale Romano. Available online: https://www.parchilazio.it/litoraleromano-schede-13072-adozione_del_piano_di_gestione_e_del_regolamento_attuativo_della_riserva_naturale_statale_litorale_r (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Contratto di Fiume, Costa e Paesaggio Arrone. Documento di Intenti. Available online: https://contrattodifiumearrone.it/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Manifesto.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Contratto di Fiume, Costa e Paesaggio Arrone. Analisi Conoscitiva Integrata. Available online: https://contrattodifiumearrone.it/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Analisi-Conoscitiva.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Contratto di Fiume, Costa e Paesaggio Arrone. Piano Strategico. Available online: https://contrattodifiumearrone.it/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Documento-strategico-integrale-3_7_21.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Contratto di Fiume, Costa e Paesaggio Arrone. Matrice Strategica. Available online: https://contrattodifiumearrone.it/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/MATRICE-STRATEGICA-Contratto-di-Fiume-rev-mag-2021.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Contratto di Fiume, Costa e Paesaggio Arrone. Programma di Azione. Available online: https://contrattodifiumearrone.it/documentazione-progettuale/ (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Brunetta, G.; Ceravolo, R.; Barbieri, C.A.; Borghini, A.; de Carlo, F.; Mela, A.; Beltramo, S.; Longhi, A.; De Lucia, G.; Ferraris, S.; et al. Territorial Resilience: Toward a Proactive Meaning for Spatial Planning. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M.; Thoms, M.C.; Flotemersch, J.; Reid, M. Monitoring the resilience of rivers as social–ecological systems: A paradigm shift for river assessment in the twenty-first century. In River Science: Research and Management for the 21st Century; Gilvear, D.J., Greenwood, M.T., Thoms, M.C., Wood, P.J., Eds.; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kwok, A.H.; Doyle, E.H.E.; Becker, J.; Johnston, D.; Paton, D. What is ‘social resilience’? Perspectives of disaster researchers, emergency management practitioners, and policymakers in New Zealand. Internat. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 19, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voghera, A. The River agreement in Italy. Resilient Planning for the co-evolution of communities and landscapes. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA. Environmental Resilience: Exploring Scientific Concepts for Strengthening Community Resilience to Disasters. Available online: https://impactbioenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/EPA-DISASTER-RESPONS-AND-RESILIENCE-RPT.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Erriquez, E. International and national best practices. In BikeFlu. Atlas of River Contracts in Abruzzo; Angrilli, M., Ed.; Gengemi Editore: Rome, Italy, 2020; pp. 164–171. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, M. New Paradigms; List: Trento, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| River, Lake, Coastal Contract | Document of Intent (Phase 1) | Formal Agreement (Phase 6) |

|---|---|---|

| RCLC Arrone | signed in 2020 | ongoing |

| CC Agro Pontino | signed in 2019 | signed in 2022 |

| CMC Riviera di Ulisse | signed in 2019 | signed in 2022 |

| LC Bolsena | signed in 2017 | ongoing |

| LC Bracciano | signed in 2019 | signed in 2022 |

| LC Paola * | signed in 2018 | ongoing |

| RC Almone | signed in 2016 | ongoing |

| RC Amaseno | signed in 2018 | ongoing |

| RC Aniene | signed in 2018 | signed in 2022 |

| CC Cavata Linea Pio | signed in 2015 | ongoing |

| RC Cosa | signed in 2017 | ongoing |

| RC Farfa | signed in 2019 | ongoing |

| RC Fibreno | ongoing | ongoing |

| RC Garigliano Basso Liri | signed in 2016 | ongoing |

| RC Melfa | signed in 2017 | ongoing |

| RC Paglia | signed in 2014 | signed in 2022 |

| RC Rio Capodacqua | signed in 2019 | ongoing |

| RC Sacco | signed in 2015 | ongoing |

| RC Tevere (C. Giubileo to Mouth) | signed in 2017 | signed in 2022 |

| RC Medio Tevere (Farfa) | signed in 2014 | signed in 2022 |

| RC Ufente | signed in 2018 | signed in 2022 |

| Territory | Province of Rome Municipalities of Fiumicino, Cerveteri, Anguillara Sabazia, Bracciano, Ladispoli, Manziana and Rome |

| Surface Area | 15.491 hectares |

| Main Water Body | Arrone |

| Natural Protected Areas Included | Riserva Statale Litorale Romano |

| ZPS Tolfetano Cerite Manziate District | |

| ZPS Torre Flavia | |

| SIC Monte Tosto | |

| SIC Sughereta del Sasso | |

| SIC Maccgia Grande di Ponte Galeria | |

| SIC Bosco di Palo Laziale | |

| SIC Caldara di Manziana | |

| SIC Macchia di Manziana | |

| SIC Monte Paparano | |

| SIC Macchia Grande di Focene e Macchia dello Stagneto | |

| Promoters | Forum Plinianum Onlus |

| Aries Sistemi S.R.L., | |

| Roman Etruscan Biodistrict | |

| Anna Maria Catalano Foundation | |

| Partners | Municipality of Cerveteri |

| Consorzio di Bonifica Litorale Nord | |

| Leonardo Da Vinci Institute of Higher Education | |

| Roman Etruscan Biodistrict Association | |

| Naval League–Fiumicino Section | |

| Aries Sistemi S.R.L. | |

| Nergal S.R.L. | |

| Agrivol S.R.L. | |

| Assonautica Acqua Interne Lazio e Tevere | |

| Anna Maria Catalano Foundation | |

| Foedus Foundation | |

| Aps Saifo “Sistema archeoambientale Integrato Fiumicino Ostia” | |

| Funds | LAZIO REGION |

| Office for Small Municipalities and River Contracts |

| Assets | General Objectives |

|---|---|

| Landscape and Nature | Protection and enhancement of landscape values |

| Sustainable Tourism | |

| Preservation and protection of natural and cultural capital | |

| Knowledge of the state and dynamics of the environment | |

| Water | Knowledge |

| Coastal area | |

| Protection of freshwater quality | |

| Protection of water quantity | |

| Hydraulic risk | |

| Hydraulic risk mitigation | |

| Protection and preservation of aquatic environments | |

| Emerging issues | |

| Quality Agriculture | Sustainable agriculture with low environmental impact |

| Multifunctional agriculture | |

| Quality | |

| New relationship between water and | |

| environmental and food education | |

| Technology | Optimization of purification processes |

| Production process waste management | |

| Early warnings | |

| Emerging issues | |

| Production chains | |

| Active Citizenship and Valorisation | Participatory planning and citizens involvement |

| Fruition | |

| Turistic valorization |

| Asset | Projects and Iniziatives |

|---|---|

| Landscape and Nature | “Amarcord” Project |

| Ideas competition “The fresh waters of the Arrone Valley” | |

| “The Tree House” Project | |

| “Discovering the Villages of Castel di Sasso and Ceri” Project “Project “Children’s River Contracts” | |

| Proposed projects: “A walk through the centuries’ project” and “Wefts of Memory” Project | |

| Water | Analysis of the state of the water in areas of high naturalness within the State Natural Reserve Litorale Romano (University of Tuscia) |

| Monitoring of the chemical-physical quantities of aquatic environments included in the WWF Oases (Aries Sisemi srl) | |

| Municipality of Cerveteri: two new purification plants | |

| Municipality of Fiumicino: one purification plant | |

| Quality Agriculture | Rome Agricultural System Project |

| Technology | X |

| Active Citizenship and Valorisation | SAIL project: “Integrated Archaeoenvironmental System of the Litorale Romano”. |

| Participation in the Living Lab Tourism of the Lazio Region | |

| Experimental pilot project “Cycling Mirabilia Lazio” |

| Action Line | Action | Subjects Involved |

|---|---|---|

| 1_Tourism | Integrated and sustainable tourist offer based on the SAIL program “Sistema Archeoambientale Integrato del Litorale laziale Project “Cycling Mirabilia Lazio” | Anna Maria Catalano Foundation SAIFO Committee |

| Visit Ostia Antica APS | ||

| Local Authorities | ||

| Coop. LeAli. | ||

| 2_Active Citizenship and Valorisation | Project “A walk through the centuries” Children’s River Contracts” Project | Anna Maria Catalano Foundation Local Authorities |

| UNI Tuscia/DAFNE | ||

| UNI SAPIENZA/CORIS | ||

| FOEDUS FOUNDATION | ||

| IIS Leonardo da Vinci Maccarese | ||

| IC Marchiafava | ||

| IC Porto Romano Fiumicino | ||

| IC Salvo D’Acquisto Cerveteri; Circolo Velico Fiumicino | ||

| Assonautica Acque Interne | ||

| 3_Agriculture | Project “Let’s transform the information measured in the field into value for the agricultural activity” Vocational training of agricultural operators Environmental and food education in schools | Aries Sistemi srl |

| University of Tuscia—(DAFNE) | ||

| AREA Science Park Trieste | ||

| International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology Trieste | ||

| Agenzia Regionale per lo Sviluppo e l’Innovazione dell’Agricoltura del Lazio (ARSIAL SpA) | ||

| Biodistretto Etrusco Romano | ||

| PrimoPrincipio Scarl, Alghero (SS) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rossi, F. Method and Practice for Integrated Water Landscapes Management: River Contracts for Resilient Territories and Communities Facing Climate Change. Urban Sci. 2022, 6, 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci6040083

Rossi F. Method and Practice for Integrated Water Landscapes Management: River Contracts for Resilient Territories and Communities Facing Climate Change. Urban Science. 2022; 6(4):83. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci6040083

Chicago/Turabian StyleRossi, Francesca. 2022. "Method and Practice for Integrated Water Landscapes Management: River Contracts for Resilient Territories and Communities Facing Climate Change" Urban Science 6, no. 4: 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci6040083

APA StyleRossi, F. (2022). Method and Practice for Integrated Water Landscapes Management: River Contracts for Resilient Territories and Communities Facing Climate Change. Urban Science, 6(4), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci6040083