The Art and Science of Urban Gun Violence Reduction: Evidence from the Advance Peace Program in Sacramento, California

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. What Is Advanced Peace?

3. Data Sources and Methods

3.1. Gun Crime Analyses

- is the predicted gun violence outcome per month.

- is the trend of gun homicides and assaults before the AP intervention (January 2014–December 2017). Time is a continuous variable which indicates the months passed since 01/2014.

- is the immediate change in gun homicides and assaults trend after the AP intervention started in July 2018. AP is a binary dummy variable indicating observation collected before (=0) or after (=1) the policy intervention.

- is the sustained change in gun homicides and assaults trend after the AP intervention started in July 2018. TimeSinceAP is a continuous variable indicating time passed since the intervention has occurred (before intervention has occurred TimeSinceAP is equal to 0).

3.2. Results of Advance Peace Sacramento on Gun Violence

3.3. Impacts of the Advance Peace Program on Participants

He called me to say that he saw another fellow out of bounds [in a rival’s neighborhood]. His brother had just been shot and they suspected it was someone from that rival ‘hood. His homies were like, ‘let’s go’. My fellow’s crew rolled up on him, but they’d just had a life-skills class together. Instead of shootin’ him, my fellow told them he was cool, sayin’ ‘that’s my sucka partner’ and he got outta there smooth.

At first he was like, ‘no way, I ain’t traveling with that fool’. So we told him ‘Ok, you can’t go’. But he ain’t never traveled like that, stayin’ in a hotel, eating a steak dinner at a restaurant, you feel me? So he eventually reluctantly agreed. The first few hours in that van, man they didn’t even look at each other. Then they found out they was listening to the same music and liked the same sports teams. After we checked into the hotel, these former rivals who wanted to kill each other a few weeks earlier, were in the pool acting-out like six-year olds. They could be the little kid they were never allowed to be. The guard and tuff exterior came down. By the end of the trip, they were smilin’ and talkin’ no problem.

- 10,858 engagements on the streets of Sacramento (these were not unique people, but the number of times an outreach worker engaged with a person);

- 16,146 h of community engagement;

- 857 service referrals for participants in the program (these could be for housing, food, drug or anger management counseling, etc.), and;

- 1657 h spent on accompanying participants to social services.

Now I got a plan for writing and releasing music and getting a driver’s license. As soon as I’m up in the morning, my whole day is set up. It’s basically put me on a program where I don’t have time to be in the streets. They want to see us living and being people, not being a statistic.

NCA#1: I finally got fellow into my car. His dad got out of prison (who I’ll be also working with) and the three of us went to lunch. We talked about some new goals and things he wanted to work on. He opened-up to his dad about the pain of missing his childhood and how everyone expected him to be just like his dad and wind up in prison. After we left, I took him to the DMV and paid for his ID. It is his first time having one. After a long day, I let him cut my hair with the new set of clippers we bought him. I’m just makin sure he doesn’t act out like everybody expect him to and be like his dad and wind up in prison.

NCA#2: Picked up fellow when we got word he was going through some things and was walking the streets by his self. To keep him from self-destructing and knowing he’s an active gang member, I knew he was vulnerable and could possibly be killed walking around in rival territory. We picked him up and took him to eat and vent. We got him to talk about his album and got his anxiety down. He said he was fighting with his people where he stay. We got his belongings and made some calls to find him another safer place to stay. It’s temporary for now, so we need to find him housing.

NCA #3: Fellow’s mother texted me notifying me that she had confiscated a gun from him. I drove to his house where we all met and discussed the situation for over 2 h. Fellow assured me that he had no intention of inserting himself into the gang activity going on in the city. I counseled him on the consequences of getting caught with a firearm and how the false sense of power can impair one’s ability to make rational decisions. I described my story and how I never left home without it, but I wound up inside for over twenty years. He seemed to be receptive and able to grasp the counseling I had given him. I will speak with him every day this week.

3.4. Street Violence Interruptions

- Mediated 202 community conflicts (these are general street-level conflicts, domestic disputes, etc., that could have escalated into gun violence);

- Responded to 66 shootings (this is when an NCA arrives at the scene of a shooting to de-escalate any potential immediate retaliation), and;

- Interrupted 58 imminent gun violence conflicts (these are conflicts where guns are present and an NCA gets in the middle of a dispute and prevents a possible homicide or shooting with an injury).

- Scenario A (direct quote from NCA):

The team had heard about a shooting in the circle area. As we responded we found that a young black man had been killed. After looking into the situation, I found out that the young man was a valley hi piru that associated with zilla. In today’s gang bang culture there was a huge threat for retaliation from multiple sides. The team was very aggressive on speaking to all sides and a situation that seemed like a guaranteed retaliation never happened.

- Scenario B (direct quote from NCA):

There was conflict between two Norteño sets and a factor (a well-known shotcaller) was shot. The victim survived and let the streets know that he was coming back for blood. The accused side denied that they were involved but felt like since they were being accused, they would take the offense. I spoke with both sides intensely and although both sides still had dislike for the other, they agreed not to retaliate with gun play.

- Scenario C (direct quote from NCA):

A well-known local rapper was captured in the video of an all-out brawl. The video had the city braced for what they believed was an inevitable gang war, especially since the local rapper just happened to be the younger brother of one Sacramento’s most notorious rappers. While the rest of the city rushed out to purchase flashlights, batteries, bottled water and canned goods, Advance Peace NCAs immediately met with influential street actors and real O.G.’s. close to the situation. One of our fellows believed we could calm the situation if we could get the main characters involved to agree to one-on-one fades (fist fight). Several meetings took place arranged and facilitated by AP NCAs with the main players involved. A fellow also took a leading role to get everyone involved to agree to one-on-one fades. No further incidents took place.

4. Limitations

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Bauchner, H.; Rivara, F.P.; Bonow, R.O.; Bressler, N.M.; Disis, M.L.; Heckers, S.; Josephson, S.A.; Kibbe, M.R.; Piccirillo, J.F.; Redberg, R.F.; et al. Death by gun violence—A public health crisis. JAMA 2017, 318, 1763–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NAS). Community Violence as a Population Health Issue: Proceedings of a Workshop; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Crime in the United States: Murder Victims by Weapon, Age & Community Type. Tables 2 & 9. 2019. Available online: https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2019/crime-in-the-u.s.-2019/topic-pages/tables/expanded-homicide-data-table-9.xls (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Fatal Injury Reports, National, Regional and State, 1981–2019, United States. 2019. Available online: https://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/mortrate.html (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC). A Public Health Crisis Decades in the Making: A Review of 2019 CDC Gun Mortality Data; CDC: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: https://archive.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg1/ (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Bailey, R.K.; Barker, C.H.; Grover, A. Structural Barriers Associated with the Intersection of Traumatic Stress and Gun Violence: A Case Example of New Orleans. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Formica, M.K. An Eye on Disparities, Health Equity, and Racism—The Case of Firearm Injuries in Urban Youth in the United States and Globally. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 68, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghton, A.; Jackson-Weaver, O.; Toraih, E.; Burley, N.; Byrne, T.; McGrew, P.; Duchesne, J.; Tatum, D.; Taghavi, S. Firearm homicide mortality is influenced by structural racism in US metropolitan areas. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021, 91, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.R.; Lawrence, J.A.; Davis, B.A. Racism and Health: Evidence and Needed Research. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2019, 40, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Urzúa, A.; Caqueo-Urízar, A.; Henríquez, D.; Williams, D.R. Discrimination and Health: The Mediating Effect of Acculturative Stress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, Z. Defund Fear: Safety Without Policing, Prisons, and Punishment; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pinderhughes, H.; Davis, R.; Williams, M. Adverse Community Experiences and Resilience: A Framework for Addressing and Preventing Community Trauma; Prevention Institute: Oakland, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey, P. Uneasy Peace: The Great Crime Decline, the Renewal of City Life, and the Next War on Violence; WW Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-0-393-35654-0. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. Expanded Homicide Offense Counts in the United States. 2021. Available online: https://crime-data-explorer.app.cloud.gov/pages/explorer/crime/shr (accessed on 8 November 2021).

- Weisburd, D.; Farrington, D.P.; Gill, C. What Works in Crime Prevention and Rehabilitation. Criminol. Public Policy 2017, 16, 415–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aufrichtig, A.; Beckett, L.; Diehm, J.; Lartey, J. Want to Fix Fun Violence in America? Go Local. UK Guardian. 9 January 2017. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2017/jan/09/special-report-fixing-gun-violence-in-america (accessed on 29 July 2021).

- Papachristos, A.V.; Wildeman, C. Network Exposure and Homicide Victimization in an African American Community. AJPH 2014, 104, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lurie, S.; Acevedo, A.; Ott, K. The Less Than 1%: Groups and the Extreme Concentration of Urban Violence; John Jay College, National Network for Safe Communities: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: https://cdn.theatlantic.com/assets/media/files/nnsc_gmi_concentration_asc_v1.91.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2021).

- Weisburd, D.; Majmundar, M. (Eds.) Proactive Policing: Effects on Crime and Communities; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Abt, T. Bleeding Out: The Devastating Consequences of Urban Violence and Bold New Plan for Peace in the Streets; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Braga, A.; Weisburd, D.; Turchan, B. Focused Deterrence Strategies and Crime Control: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of the Empirical Evidence. Criminol. Public Policy 2018, 17, 205–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corburn, J.; Boggan, D.; Muttaqi, K. Urban safety, community healing & gun violence reduction: The advance peace model. Urban Transform. 2021, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culyba, A.J.; Ginsburg, K.R.; Fein, J.A.; Branas, C.C.; Richmond, T.S.; Wiebe, D.J. Protective effects of adolescent-adult connection on male youth in urban environments. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 58, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ginwright, S. The Future of Healing: Shifting from Trauma Informed Care to Healing Centered Engagement. Medium. 2018. Available online: https://ginwright.medium.com/the-future-of-healing-shifting-from-trauma-informed-care-to-healing-centered-engagement-634f557ce69c (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- Sakala, L.; La Vigne, N. Community-Driven Models for Safety and Justice. Du Bois Rev. Soc. Sci. Res. Race 2019, 16, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butts, J.A.; Roman, C.G.; Bostwick, L.; Porter, J.R. Cure violence: A public health model to reduce gun violence. Ann. Rev. Public Health 2015, 36, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lowery, W.; Rich, S. In Sacramento, trying to stop a killing before it happens. The Washington Post. 9 November 2018. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/investigations/in-sacramento-trying-to-stop-a-killing-before-it-happens/2018/11/08/482be50e-dadd-11e8-b732-3c72cbf131f2_story.html (accessed on 13 October 2021).

- Slutkin, G.; Ransford, C.; Zvetina, D. How the Health Sector Can Reduce Violence by Treating it as a Contagion. Am. Med. Assoc. J. Ethics 2018, 20, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Matthay, E.C.; Farkas, K.; Rudolph, K.E.; Zimmerman, S.; Barragan, M.; Goin, D.E.; Ahern, J. Firearm and Nonfirearm Violence After Operation Peacemaker Fellowship in Richmond, California, 1996–2016. AJPH 2019, 109, 1605–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- City of Sacramento, California. Gang Prevention & Intervention Task Force. 2019, Unpublished Data.

- Muttaqi, K. (City of Sacramento, CA, USA). Personal Communications, 2020.

- Wolfe, J.; Kimerling, R.; Brown, P.; Chrestman, K.; Levin, K. The Life Stressor Checklist-Revised (LSC-R) [Measurement Instrument]. 1997. Available online: http://www.ptsd.va.gov (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Liu, G.; Wiebe, D.J. A Time-Series Analysis of Firearm Purchasing After Mass Shooting Events in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e191736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bernal, J.L.; Cummins, S.; Gasparrini, A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: A tutorial. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skogan, W.G.; Hartnett, S.M.; Bump, N.; Dubois, J. Evaluation of CeaseFire-Chicago; Institute for Policy Research, Northwestern University: Evanston, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Picard-Fritsche, S.; Cerniglia, L. Testing a Public Approach to Gun Violence: An Evaluation of Crown Heights Save Our Streets, a Replication of the Cure Violence Model; Center for Court Innovation: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Available online: https://www.courtinnovation.org/sites/default/files/documents/SOS_Evaluation.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2021).

- Braga, A.A.; Zimmerman, G.; Barao, L.; Farrell, C.; Brunson, R.K.; Papachristos, A.V. Street Gangs, Gun Violence, and Focused Deterrence: Comparing Place-based and Group-based Evaluation Methods to Estimate Direct and Spillover Deterrent Effects. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 2019, 56, 524–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachristos, A.; Kirk, D. Changing the Street Dynamic: Evaluating Chicago’s Group Violence Reduction Strategy. Criminol. Public Policy 2015, 14, 525–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Gun Homicides | Gun Assaults | Gun Homicides + Assaults | City of Sacramento, CA Population | Gun Homicides + Assaults Rate (100,000) | Annual Change in Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 19 | 183 | 202 | 485,193 | 41.63 | NA |

| 2015 | 31 | 252 | 283 | 490,715 | 57.67 | 38.52% |

| 2016 | 24 | 280 | 304 | 495,200 | 61.39 | 6.45% |

| 2017 | 23 | 247 | 270 | 501,890 | 53.80 | −12.37% |

| 2018 | 29 | 247 | 276 | 508,517 | 54.28 | 0.89% |

| 2019 | 19 | 192 | 211 | 513,620 | 41.08 | −24.31% |

| Area | Mean, 18-Month Periods January 2014–June 2018 | 18-Month AP Fellowship (July 2018–December 2019) | Absolute Change | Percent Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

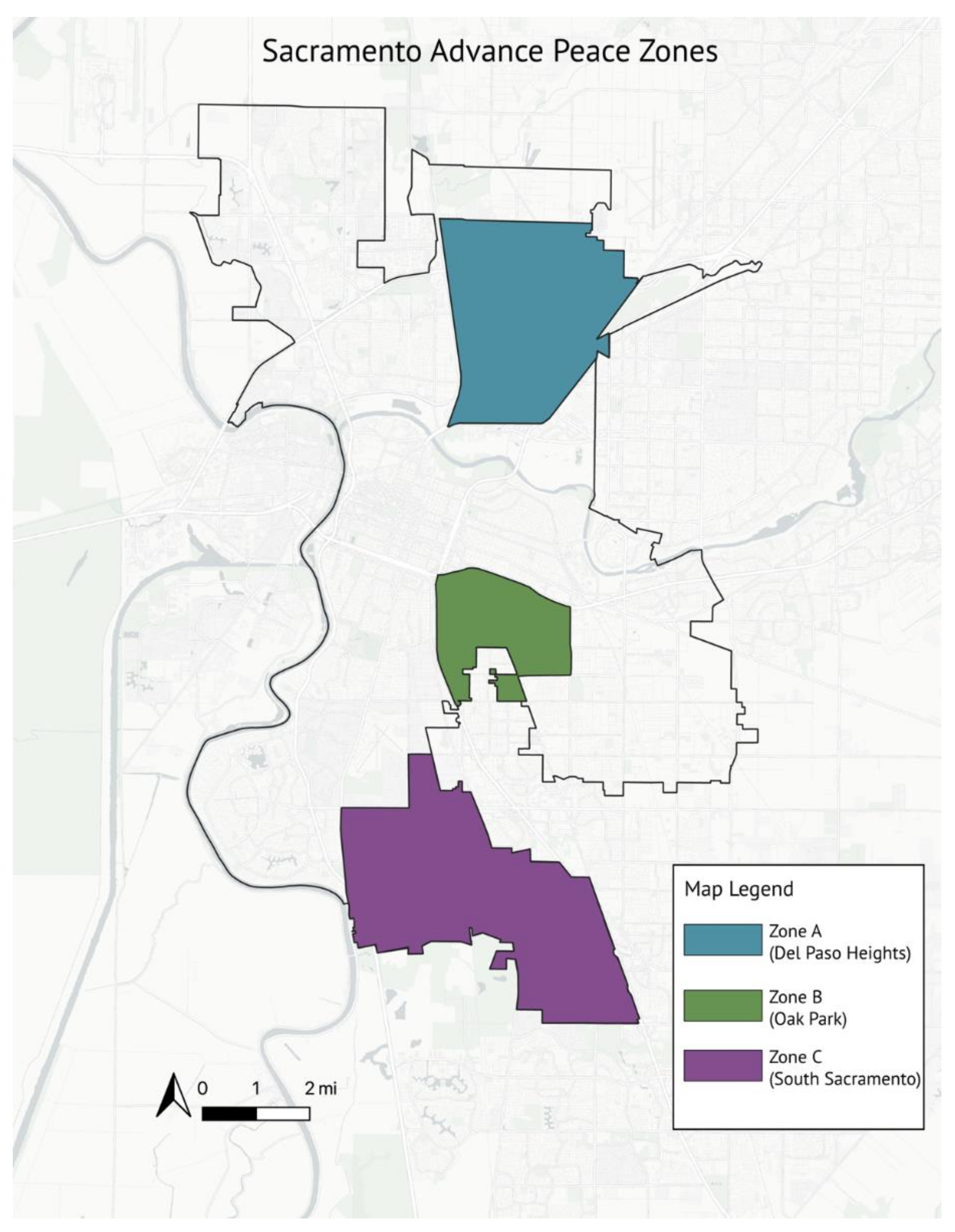

| All Advance Peace Zones (combined) | 248.3 | 203 | −45.3 | −18.2% |

| Del Paso Heights | 104.0 | 74 | −30.0 | −28.8% |

| Oak Park | 47.3 | 38 | −9.3 | −19.7% |

| South Sacramento | 97.0 | 91 | −6.0 | −6.2% |

| Non-Advance Peace Zones | 146.3 | 159 | 12.7 | 8.7% |

| City wide | 394.7 | 362 | −32.7 | −8.3% |

| Area | Gun Homicides: B | Gun Homicides: SE | Gun Assaults: B | Gun Assaults: SE | Gun Homicides + Assaults: B | Gun Homicides + Assaults: SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City-Wide | −0.036 CI(−0.19,0.12) | 0.07931 | −0.778 * CI(−1.32,−0.23) | 0.2741 | −0.814 * CI(−1.4,−0.23) | 0.2915 |

| AP Zones only | −0.048 CI(−0.16,0.06) | 0.05634 | −0.32 CI(−0.73,0.09) | 0.2062 | −0.367 CI(−0.82,0.09) | 0.2282 |

| Fellow Characteristic | % Yes | n |

|---|---|---|

| African American | 96% | 48 |

| Male | 98% | 49 |

| Unemployed | 82% | 41 |

| Finished High School | 52% | 26 |

| Ever suspended from school | 88% | 44 |

| Was/is in foster care system | 38% | 19 |

| Is a parent | 70% | 35 |

| Was/is/ever homeless | 74% | 37 |

| Was/is/ever food Stamp recipient | 74% | 37 |

| Prior gun arrest | 66% | 33 |

| Prior incarceration | 96% | 48 |

| Parent is/was incarcerated | 80% | 40 |

| Previous gunshot injury | 84% | 42 |

| Fellow Characteristic | % Yes | n |

|---|---|---|

| Alive | 98% | 49 |

| New gun injuries | 6% | 3 |

| New gun arrest/charge | 10% | 5 |

| Received assistance for food and/or housing | 90% | 45 |

| Received Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) | 100% | 50 |

| Received Life Coaching | 100% | 50 |

| Received mental health counseling | 80% | 40 |

| Received anger management counseling | 64% | 32 |

| Attended group life skills classes/ healing circles | 98% | 49 |

| Received job readiness /paid internship/employment | 38% | 19 |

| Attended out-of-town excursions or transformative travel | 84% | 42 |

| Reported improved mental health/outlook on life | 84% | 42 |

| Reported having a caring adult to talk to, such as an NCA, when faced with a difficult situation | 98% | 49 |

| Reported peaceful resolution of a conflict that previously might have resulted in gun use | 90% | 45 |

| Rated AP outreach worker one of most important adults in life | 98% | 49 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Corburn, J.; Nidam, Y.; Fukutome-Lopez, A. The Art and Science of Urban Gun Violence Reduction: Evidence from the Advance Peace Program in Sacramento, California. Urban Sci. 2022, 6, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci6010006

Corburn J, Nidam Y, Fukutome-Lopez A. The Art and Science of Urban Gun Violence Reduction: Evidence from the Advance Peace Program in Sacramento, California. Urban Science. 2022; 6(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci6010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorburn, Jason, Yael Nidam, and Amanda Fukutome-Lopez. 2022. "The Art and Science of Urban Gun Violence Reduction: Evidence from the Advance Peace Program in Sacramento, California" Urban Science 6, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci6010006