1. Introduction

This paper asks the question, to what extent does Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) management present a situation that maintains cultural memory and achieve psychosocial well-being?

HULs have received more attention after the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) recommendations in 2011 which aimed at protecting historic urban settings from deterioration and fragmentation resulting from uncontrolled urban developments [

1]. The recommendations defined HUL as “[t]he urban area understood as the result of a historic layering of cultural and natural values and attributes, extending beyond the notion of ‘historic cent[er]’ or ‘ensemble’ to include the broader urban context and its geographical setting” [

2]. This definition included the intangible values previously largely ignored in HUL in old conservation policies and approaches that privileged values of the physical environment.

An important intangible value in our landscapes is ‘memory’. Raadik-Cottrell (2010) argued that landscapes are “the medium through which multiple histories are simultaneously remembered and forgotten” [

3] so urban landscapes could be seen as a medium for our memories and sense of place to exist [

4]. Some of these memories are individual (personal) but other ones are social (collective) often named as ‘cultural memory’.

Cultural memory (collective memory), has been studied through a wide range of interdisciplinary sciences including history, psychology, geography, sociology and built environment. But, when it comes to the relationship of cultural memory to issues of spatial configuration and city heritage the number of the disciplines involved dramatically decrease. Maurice Halbwachs, the French sociologist, was the first to introduce the term “collective memory” in his books ‘The Social Frame Works of Memory’ (1992 and 1925) and ‘On Collective Memory’ (1980 and 1950). His conception of collective memory was founded on the contrast between collective and individual memory, as he calls the individual memory “personal” and “autobiographical” while the collective is “social “and “historical” memory [

5]. He explained that “autobiographical memory” is the memory of things that a person has experienced and remembers while, “historical memory” extends beyond this to include information about the world context of personal experience.

Following this concept, the historian Pierre Nora engaged in more spatial collective memory studies especially in geography and built environment domains. He discussed how certain sites can engender emotions and embody national memories [

6].

Both Halbwachs and Nora inspired other scholars to write on place and memory. The architectural theorist Aldo Rossi was one such person. He introduced the concept of “collective memory” in architecture and urban design studies through the concept of “urban memory” outlined in his book ‘The Architecture of the City’ [

7]. He argued that heritage site preservation encouraged the retention of memories and led to the protection of national identities [

8]. Boyer’s (1994) book ‘The City of Collective Memory’ explored how city images relate to collective memory and every day urban experiences and how this memory is developed. Focusing on the importance of memory in preserving our past by recalling our previous experiences and discussing the difference between history and memory she held “that when memory does not have a link to the lived experience, it is reduced to history or a fragmented re-construction of the past” [

9].

These theorists showed that there were important linkages between cultural memory and place and experience that engender collective images and perceptions that help to form the character of city places. Kevin Lynch pointed to the links between planning and psychosocial well-being. In ‘A Theory of Good City Form’ (1981) he stated that the “crucial function of planning is to nourish psychosocial ties to places by pursuing the values of community, continuity, health, well-functioning, security, warmth, and balance”. Values which coalesced in his idea of the “Image of Time” and its importance for psychic health [

10].

Psychosocial well-being is a growing area of research and its multi-disciplinary nature means that it straddles a number of sciences and research fields such as: environmental psychology, geography and sociology. The concept highlights the close connection between psychological aspects of our experience (e.g., our thoughts, emotions, memories and behavior) and our wider social experience (e.g., our relationships, traditions and culture) [

11]. In architectural studies psychosocial well-being shows strong cross relations with the concept of “sense of place”, theoretically sketched as the integration of psychological, social and environmental operations in relation to physical places [

12].

Sense of place has been theorized by a number of people (e.g., Relph 1976; Tuan 1980; Steele 1981; Eyles 1985; Jackson 1994 and Hay 1998). Datel and Dingemans (1984) defined it as the complex bundle of meanings, symbols and qualities that a person or a group associate with a particular region [

13]. David Hummon (1992) took this concept of sense of place further by adding “sense of place is inevitably dual in nature, involving both an interpretive perspective on the environment and an emotional reaction to the environment” [

14]. Stewart (1998) considers sense of place as an umbrella concept that captures all the relationships people form with places such as emotional bonds; the strong felt meanings, memories, values and symbols; the valued qualities of the place; and the awareness of the historical and cultural significance of the place [

15].

Sense of place is composed of three elements: physical setting, activity and meaning [

16]. We cannot think of a physical setting without events as narration of an event involves conveying the meaning or value that the setting carries for its users [

17]. These narrative projections provide a link between memory and setting. In this context they prompt a clear sense of the past and help develop a sense of place and belonging through the reinforcement of place attachment and identity [

18]. Place attachment is the bond that people create with their places and is composed of three components; the affective, cognitive and behavioral component [

19]. It was marked as the emotional bond formed by people with places which are significant to them and in which they feel comfortable and safe, and towards it they try to maintain a certain contiguity [

20]. This means that protecting the physical environment of a place, in its role as a memory container, plays an important part in carrying cultural memories into urban landscapes creating an emotional sense of place that affects the experience of a place and ultimately the well-being of its users [

21].

The ongoing global urban transformation has an impact on city identities and users’ experiences especially in historic cities. The current adopted urban conservation practices concentrate mainly on tangible benefits, such as improving infrastructure and renovating the urban fabric to suit growing populations [

22]. However, in many cases current governmental practices tend to underestimate studies concerning psychosocial values and sense of place, which have shown to be important for maintaining the image and identity, notably, of historical cities [

18].

Alexandria is the second capital of Egypt and is an ancient historical city experiencing major urban changes due to ongoing governmental urban management plans to cope the growing population needs and urban extensions. Orabi Square is one of the most important HUL within the Alexandria city urban fabric. A public square that has witnessed many historical events. Currently the square is neglected, and merely used as a place to pass through rather than used as a public square. Its function is to direct traffic flow rather than for public gathering causing physical and cultural decay through loss of emphasis on local primary memory, function and social interaction.

This paper focuses on how cultural memory can be maintained and used as a tool to enhance the HUL management plan for Orabi Square in order to create a better place experience by recalling the square’s lost sense of place and identity, enhancing the psychosocial well-being of its users.

3. Results

The research participants in the Orabi Square on site interviewees and Facebook contributors represented different components and factors of cultural memory in their interviews and comments. They showed the relationship between cultural memory with the concepts of psychosocial well-being, sense of place, place identity, place attachment and a landscape approach. The concepts and components that were extracted through the qualitative content analysis for the interview manuscripts with relation to the proposed conceptual model of the research have reached the following findings:

3.1. Memories and Its Value (Cultural or Individual)

The value of memories and an appreciation of their effect and significance in space experience revealed that mobile users were concerned about the site’s collective memories and the place identity and character when they experienced the site.

On the other hand, the static users were more connected to personal memories and with contexts such as their shops or houses rather than to the site as a whole (

Figure 6).

3.2. Site Distinctiveness and Well-Being (Self-Identifiers)

All of the study participants agreed on the site’s tangible and intangible distinctiveness. Adjacent monuments and buildings such as the memorial of the ‘Unknown Naval Soldier’, the former French Consulate, the Alexandria Primary Court House and the El Hakaneya Court House were significant for the Orabi Square users. Interviewees indicated that the presence of these buildings engender feelings of uniqueness and belonging and maintain cultural memories, supporting their psychosocial well-being.

“The memorial of the Unknown Soldier is so unique for me, I have used to see it every day since I was a kid. Also, because the governorate perform some army shows when Egypt have official visitors and this gives me the feeling of pride and glory”—58 year old male interviewee (sample of analyzed comments).

Intangible emotions such as the nostalgic feelings towards old images of the square on Facebook show that people still have attachments despite major changes to the landscape and that people feel a continuing regard for the place that supports protecting its identity.

“I feel nostalgic when I come to this place it is where I spent the best of my early youth. It is the real Alexandria in my eyes. A kind of an emotional tie I think despite of the nowadays reality. Maybe I’m nostalgic to the old image that is preserved in my memory but, I still love to have a walk in the place.”—Facebook comment by Driman elbawab 57 years old (sample of analyzed comments).

3.3. Social Reminders (Activities and Events)

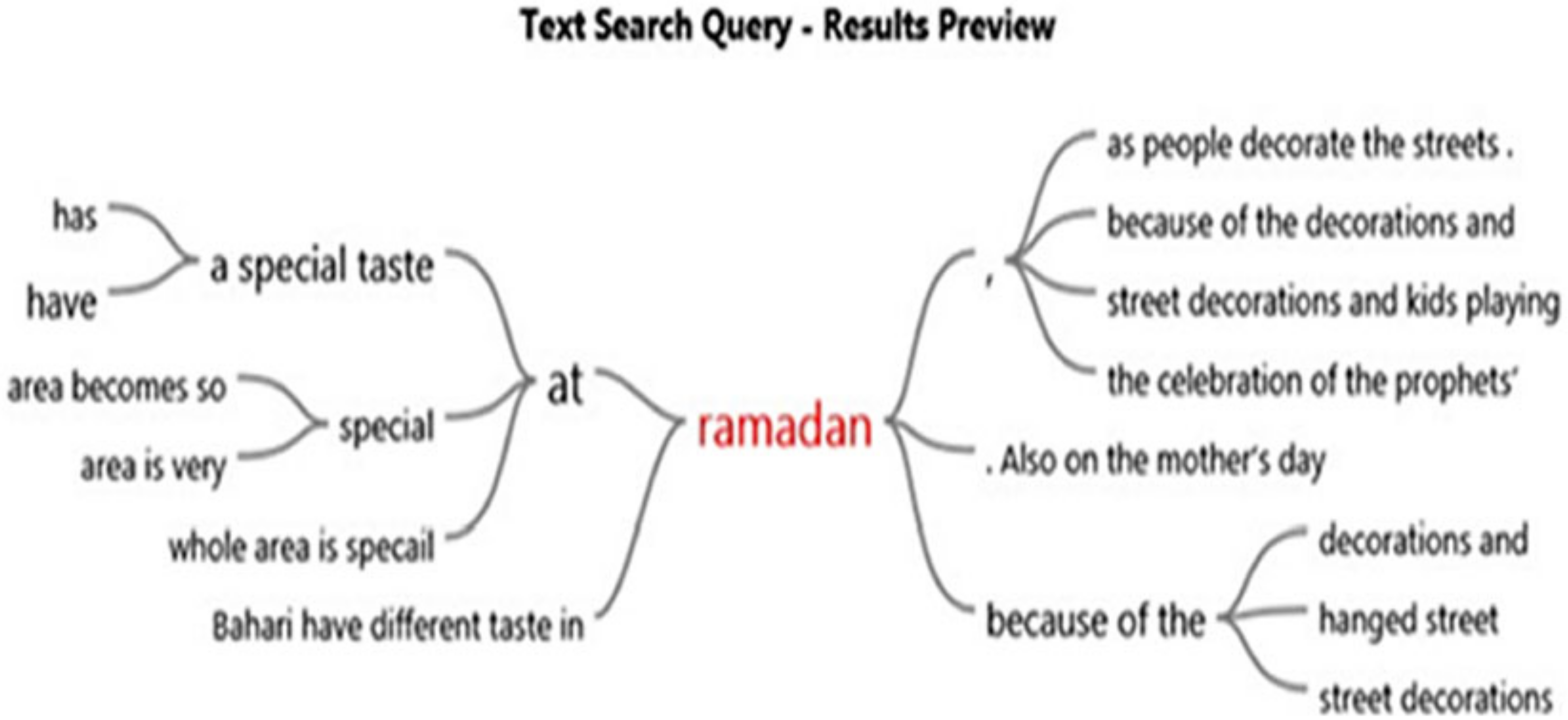

Most of the interview participants (10 out of 12) agreed that the Orabi Square context acts as a social reminder for cultural memories through the activities or the events that are connected to it. Most activities tended to be commercial as many participants have memories as children coming with their parents to buy things from shops at the site. The place was also important for celebrating Ramadan and the birth of the prophet Mohamed. This appears in the Nvivo extracted word query

Figure 7. They described that it’s all about the spiritual effect that this place possesses at that time of the year and how the area becomes a vibrant and festive place possessing good sensations. It makes the area more attractive for all the Alexandrians that celebrate these festive occasions and enjoy this site experience.

“The whole area becomes so special at Ramadan because of the hanged street lights and decorations give a spiritual feeling. You know it’s the feeling of kindness and family gatherings, also the celebration of the prophets’ Mohamed (peace be upon him) birth date is special time as people come to buy sweets and gifts for their families so the area becomes more livable.“—25 years old male interviewee (sample of analyzed comments).

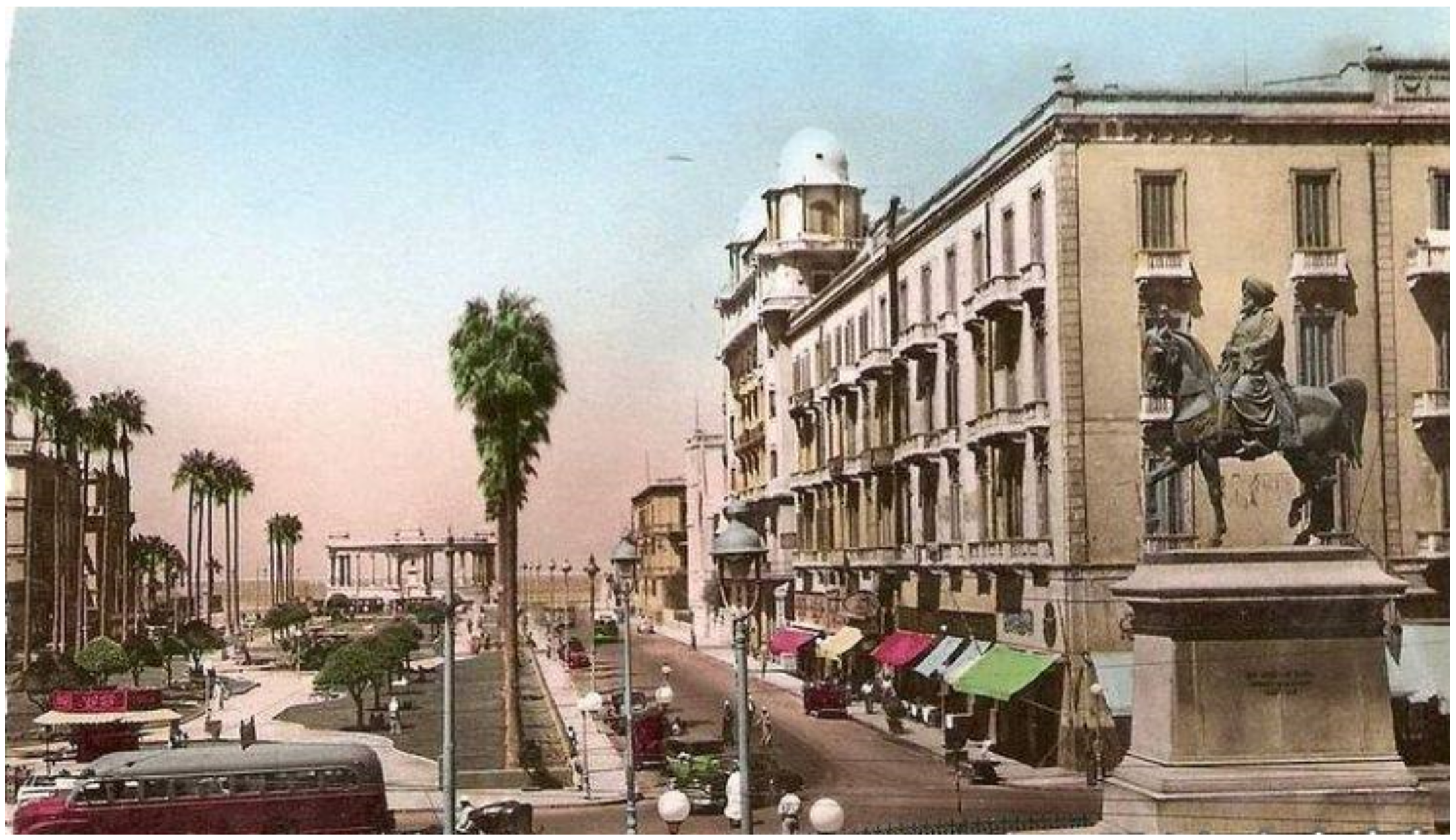

3.4. History Stored in the Site (the Value of History)

All participants considered the Orabi Square to be a historical place that is connected to the most important events of the old and contemporary history of Alexandria. All the Facebook comments reflected a nostalgia for the old times when it was called “Les Jardins Français”. The on-site interviewees (nine out of 12) were more nostalgic and remembers President Nasser’s (the President from 1954 to 1970) autocratic socialist rule when the gardens were removed, and the square was transformed to a tram station and transportation hub.

“I don’t like the acting square design, I used to like the presence of the station it was creating a sense of a hub attraction point. While the gardens now causing a lot of problems because they are not maintained or served.”—52 years old male interviewee (sample of analyzed comments).

Younger generations (five among the interview study subjects) were concerned with the more contemporary historical events that accompanied the Square such as; the protests in the 2011 Egyptian revolution and camping at the Square Gardens.

The interviewees indicated that they understand that the site is historic, despite that sometimes they do not know much information about the details of this history. This is a culture of collectivity as they their opinion of appreciating the site as historically important is produced from having cognitive place attachment that originates from their collective beliefs, thoughts, memories and narratives.

3.5. Land Use Transformation and Identity

Changes in the design of the Square has led to huge changes in its identity and perception by people who use the area.

“I have been using this place my whole life, and I feel so confident with interacting with the people in here, I have been raised here as I mentioned before. But now days you feel that the people changed than before, I call them intruders who came to work here I’m not confident with them at all.”—58 years old male interviewee (sample of analyzed comments).

Most of the static users (four out of six static interviewees) expressed that they feel happier about the Square when it was a traffic station, while the mobile users were missing much of the iconic French Gardens. But both groups were not happy with the ongoing plan and situation.

One of the most important comments that came from this site to describe this feeling of loss of an old beauty was through the Facebook group commenting on an old photo of the French Gardens period in

Figure 8:

“The journey of the square from the European beauty to the informal ugliness”—Ahmed Ragheb (sample of analyzed comments).

The comment reflects how people judge the ongoing situation, ill-conceived present planning and how they preferred the old gardens, and conveying feelings of sadness and loss.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to explore how far the HUL current management policies and actions did maintain cultural memory to achieve psychosocial well-being in the context of Orabi Public Square in Alexandria, Egypt. First the study indicated that people remember and appreciate the importance of the Square through individual and cultural memories, activities and events, the place distinctiveness, transformed identity and the history stored in its physical setting.

The dimensions of the cultural memories and its relation to sense of place and psychosocial well-being were expressed in different ways by the participants of the study as a sample of various kinds of experiences between static and mobile users’ perceptions. The findings indicated that intangible values such as memories, sense of place, place attachment and identity are very important for marking the place experience and are responsible for psychosocial well-being. This approach supports prior studies when differentiating between collective and individual memory and revealed the importance of the HUL to be our rich historical record and a repository for our memories [

5,

35].

Cultural memory appeared to be more important for mobile users than static users. It was important for them that the site keep its spirit and to warrant the same experience every time visit. This matches Kate Darian Smith’s (1994) understanding of the concept of cultural memory as “… collective memory is a record of resemblances, similarities, that is kept alive by continuous reworking and transmission” [

36]. This is the remembered collective dimension which keeps the site attractive and enjoyable. So, the disturbance of this image (cultural or collective memory) results in feelings of loss of the sense of place. But this finding is opposite to that supported by previous studies. Maria Lewicka 2008 argued that people inhabiting a neighborhood (static users) will show more interest in the past of a place and will be more attached to it [

19]. However, in this study static participants were more concerned with their individual memories and not to the urban landscape as a whole. Even their appreciation of the site and its importance came from personal experiences or family history as if they are separating themselves and living in a capsule.

Participant’s comments appreciate site distinctiveness as one of the important values when designing for well-being. Protecting tangible identifiers such as monumental buildings and intangible identifiers such as nostalgic images both stimulates cultural and collective meanings. Creating a sense of identity and place attachment and supporting the concept of “hearth”—which is the idea of safety and intimacy associated with every day places that create social bonds such as a family kitchen at home, and in our case community places [

37]. It creates a feeling of safety and satisfaction that everything is continuous (continuity) and still as we know it. So, when site identifiers are lost the sense of place encloses feelings of placelessness causing emotions of grief and loss.

Another attribute composing cultural memory that showed as important for people to enjoy their urban landscapes is that these landscapes work as a context for their events and the practice of ritual and traditions. Study participants revealed enjoyable feelings towards visiting the site during Ramadan month. These feelings were connected to practicing their traditions and enjoying the festive spirt. This matches the definition of cultural memory by Ardakani & Oloonabadi (2011) [

38] to be a “series of events collectively remembered by a group of people who share it and involve themselves in shaping it”. That square (and the whole urban area) at that time of the year maintains a special experience creating a sense of place that people enjoy and want to protect and pass to their future generations.

The Square’s differing names, associated “monumental buildings”, and various master plans are significant in reflecting its rich history accompanied by the important events it hosted. “History” is shown to be an important element for individuals and social groups to reproduce cultural memories and relate to a place [

5]. The community and cultural value of a place tends to increase in relation to the amount and the impact of historical events that took place over its history [

4]. This was a significant comment by participants even when connecting its changes in physical shape with different periods of time. Also, the nature of collectivity was so present in appreciating the fact that the Square is a historical site. While some of the participants did not specifically know the sites’ history they still recognised it as a historical site to be proud of.

It was noticeable how the changes in the site plan through different historical periods was associated with a change in the occupant’s demography and lifestyle and reflected in attitudes to the urban place. These changes generated a different sense of place and accordingly place identity. This is why some scholars consider cultural memory a type of “nationalist memory” a memory that describes the geography of belonging, an identity captured in a specific landscape and is inseparable from it [

39]. Cultural memory then creates a feeling of responsibility towards that site as people feel that it needs to be protected and preserved as its part of their identity and to serve the idea of “nationalism”. So, when they fail to protect the place identity they experience feelings of sadness through losing their attachment to the places they used to know. This illustrates why history, memories and local identity are important considerations in understanding how people enjoy their urban places [

40]. The participant’s comments reflect their resentment and feelings of loss about the ongoing neglect as they consider past planning lacked meaning. In this context planners, urban designers and city administrators should consider the importance of cultural memories in HUL management practices for a better place experience and psychosocial well-being and implement these in planning policy.

5. Conclusions

This paper began with questioning the way cultural memory can be maintained and used as a tool to enhance the HUL management plan for Orabi Square. The intention was to create a better place experience by reclaiming the Square’s lost sense of place and identity and enhancing the psychosocial well-being of its users.

As one of the latest urban heritage management tools, UNESCO’s HUL approach understands urban areas to be a historic layering of tangible and intangible heritage [

41]. The real challenge for implementing this approach is to honor this intangible dimension through recognition of cultural memories which may improve the quality of the urban space and to enhance psychosocial well-being.

This paper revealed how recalling cultural memories were neglected through the management plans of the HUL of Orabi Square (1960 and 1980 plans). Which directly affected people’s sense of place and site experience and created the feelings of loss and sadness. So, from being a beautiful political, social and economic hub of Alexandria, the Square’s image in peoples’ mind has been reduced to a congested traffic roundabout. Cultural memories as shared memories of the site users can contribute to providing a better place experience by reinforcing social networks, community participation and collaboration, reinforcing identity and civic pride and improving psychic health creating a psychosocial well-being.

It is important for the government planning agencies to recognise the site as a cultural urban space for gatherings and events and ensure that the redevelopment and management plan reflects its historical value by memorializing the events that took place there. The plan should incorporate preservation and protection of the surrounding monumental buildings and place sensitive design on any newly proposed built form.

This could happen through social engagement, as the government would need to consider the factor of cultural memories when dealing with HUL projects and give more time for proper data collection. This is where social groups could play a role by conducting interviews with site residents and visitors to discover memories that they want to protect and transmit to future generations and to protect the site’s identity and experience.

Also, more efforts need to be given to ‘public awareness’ as societies need to learn the importance of participation in protecting their city identity. However, this should be in parallel with working on gaining their trust that their say will be recognised and incorporated.

This proposed framework is only a starting point of a series of future studies aiming towards a better place experience and acquiring psychosocial well-being in Historic Urban Landscapes (HUL) through maintaining cultural memories when managing urban heritage. This appears a necessity for HUL projects to improve the quality of urban social life.