Abstract

Since the publication of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, governance for sustainable development has grown and several national, regional and local sustainable development strategies have been adopted. A sustainable development strategy can serve as a political control instrument and management tool. For the development and implementation of such a strategy at the local level, municipalities might use citizen participation approaches. There exist manifold ways of consulting civil society, representing different levels of decision-making power. The analysis of this article is divided into two parts. First, we report on a case study of the pilot project “Global Sustainable Municipalities” located in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany and assess the current status of the use of citizen participation formats for adopting a local sustainable development strategy. Second, we developed a model of citizen participation approaches during different phases of adopting a sustainable development strategy. The purpose of this model is to assess the potential decision-making power of citizens during the phases and to help municipalities to get an orientation on participation possibilities. The results show that most municipalities count on participation mainly in the implementation phase of the strategy, less during developing it. Our model, however, demonstrates participation possibilities for each of the phases.

1. Introduction

With the Agenda 2030 and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the United Nations are making an attempt towards ending poverty, protecting the planet and ensuring prosperity for all [1]. The 17 goals, adopted in 2015, aim at promoting sustainable development regarding all its manifestations, i.e., environmental, economic and social dimensions. Sustainable development can be defined as a “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [2] (p. 37). Rather than focusing on development in developing countries, the Agenda 2030 demands action of all countries. For this purpose, a sustainable development strategy (or sustainability strategy) can serve as a political control instrument and management tool. A sustainable development strategy includes methods and tools for strategically implementing and monitoring sustainable development on the national, regional or local level. Governance for sustainable development has grown immensely in the past years, and several national sustainable development strategies have been adopted [3].

Likewise, many cities and municipalities around the world aim at strategically becoming more sustainable with regard to the economic, environmental and social dimension, and to implement the SDGs on the local level. With goal 11—“Sustainable cities and communities”—the role of cities and their responsibility in a global world is also stressed within the SDGs. Hence, with more than half of the world’s population living in cities [4], this “Urban Sustainable Development Goal (USDG)” [5] gives attention to the global trend towards urbanization. Besides, the content of SDG 11 and its targets is linked to all other SDGs, which implies the importance of local governments for contributing to a sustainable development. During the third UN Conference on Housing (Habitat III) in 2016, the New Urban Agenda was adopted which provides a guideline for future urban development. In particular, it refers to SDG 11 and thus further highlights the role of cities for sustainable development [6]. Local municipalities and cities are places where the implementation of sustainable development strategies is put into practice. The design of such a strategy should not be seen as a fixed product, but rather a continuous process, which includes the stages analysis, decisions, planning, implementations and reviews [7]. Smart sustainable cities can thereby contribute to the SDGs by an integrated information ecosystem [8]. Furthermore, smart cities foster an improvement of participation and equity [9].

The process of adopting a sustainable development strategy should include the participation of different stakeholders [7]. In general, democratic governance is not limited to top-down concepts, but also entails bottom-up approaches, including citizens into decisions and policy-making. Concepts of open government foster transparency, participation, and collaboration [10]. By allowing deliberative processes and including citizens into the debate, progress towards a sustainable development can be made. Similarly, the SDGs, which were themselves developed with the support of citizens’ involvement [11,12], “will not be achieved without significant public awareness and engagement” [13] (p. 302). The formulation of the SDGs also includes the importance of participation, for example, SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institution) entails target 16.7 “Ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making at all levels” [14]. For citizens, participation can result in advantages such as achieving education and democratic skills, and to some extend gaining control over the policy process, whereas governments may benefit by learning from the citizens, building trust and making better informed policy decisions [15]. Local governments can further improve sustainable development initiatives by collaborating with citizens [16]. Citizen participation is of particular importance for sustainable development, as the concept is normatively charged and represents a changing society with increasing social and environmental interactions [17].

The goal of this study is to contribute to the debate of citizen participation and local sustainable development governance, by performing a case study. We analyzed sustainable development strategies at the local level in order to assess the current use of citizen participation formats for adopting these. We concentrated on the German pilot project “Global Sustainable Municipalities North Rhine-Westphalia” (https://www.lag21.de/projekte/details/global-nachhaltige-kommune/) initiated by the working group “LAG 21 NRW” which advises municipalities in the development of sustainability management systems. They use a participative planning approach that has been applied in more than 50 German municipalities as well as more than 20 countries all over the world (https://www.lag21.de/themen/integrierte-nachhaltigkeitsstrategien/), which demonstrates the international relevance of the pilot project.

This article is organized as follows: The next section provides an overview on citizen participation formats as described in the literature and presents our research questions. After that, the case study is depicted, as well as the methodological approach. Subsequently, the results are presented, followed by our model of citizen participation for adopting a local sustainable development strategy, as well as a discussion and conclusion of the findings.

2. Citizen Participation Formats

Citizen participation can take several forms. There exists a variety of different participation formats, including different target groups and objectives, as well as facilitating different levels of power on the parts of the participating citizens. The “Ladder of Citizen Participation” [18] differentiates between eight types of participation and non-participation: manipulation, therapy, informing, consultation, placation, partnership, delegated power and citizen control. In that order, an increasing power of citizens can be detected. Furthermore, various participation formats are suitable for problems and topics on different abstraction levels. With regard to the design and implementation of sustainable development strategies, not every participation format may be a meaningful contribution to each of the phases. Based on the format of choice, the citizens’ decision-making power differentiates. Hence, “one of the main challenges is to measure the degree of influence that citizens have had on a decision-making process” [19] (p. 207).

The Handbook of Citizen Participation [20] gives an overview on several global participation formats and summarizes their goals and typical fields of application and served as a starting point for our literature review. In particular, each method of participation is assigned to objectives and desired effects of the process. These objectives are adapted from the “Ladder of Citizen Participation” [18] and presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Objectives of Citizen Participation Formats [20].

The right column of Table 1 entails examples of citizen participation formats for each objective. The main goal of a National Issues Forum is information sharing at the local level and an exchange of opinions, but less consulting decision-makers. Hence, the decision-making power of citizens remains low. Citizen participation within a National Issues Forum aims at enabling citizens to use and adopt democratic skills during structured discussion panels [20]. Citizens discuss specific, predefined political topics, whereby a moderator instructs them. Prior to the discussions, citizens are encouraged to read information on the specified topics, in addition, questionnaires can be distributed before and after the event [21].

Deliberative Polling is an approach which entails the use of two polls in different stages: one ad hoc poll on a certain topic distributed to a random sample of citizens, followed by an event which aims at informing the participants, as well as a second poll after the event. During the event, participants have the opportunity to discuss the topic with experts, politicians or other relevant stakeholders [20]. The main goal of this method is information-sharing, but also to measure changes of the participants’ opinions after the information event [22]. A large amount of citizens, who should be randomly chosen and form a representative cross-section of the population, can take part in these events. However, the decision-making power of participating citizens remains low, as the priority lies on information-sharing. Furthermore, the outcome of such events depends also on the selection of the invited experts, who discuss with the participants [23].

Similarly, the idea of a Consensus Conference is to bring science and practice together. A dialogue between experts and laypersons, in particular regarding technology assessment, but increasingly further social and economic topics is desired through this method [20]. Mostly, the format is open to the public and accompanied by the media. Before the event takes place, information material is shared with the participants. Similar to Deliberative Polls, the influence of citizens in this process is of an indirect nature, as the discussions may help politicians to obtain new perspectives on concerns and opportunities regarding certain technologies. “Consensus conferences do not promise any miracles, and it is very important to make this clear to the citizens before engaging on the work” [24] (p. 336).

The format of an Appreciative Inquiry originates from change management in organizations and can be used in order to focus on those elements that work well, and not to solely highlight shortcomings and problems [20,25]. The format aims at creating a vision for change based on existing strengths and to define reasons for success. The idea is to create motivating effects by concentrating on the positive conditions. In 2009, the city of Cleveland organized an Appreciative Inquiry entitled “Sustainable Cleveland 2019”, aiming at transforming Cleveland to a sustainable city. The project was deemed successful and “using a strength based approach enabled building momentum on an established, successful base with a positive vision” [25] (p. 57).

The goal of an Open Space Conference is to find a solution for a guiding theme or problem (e.g., sustainable development). There are no predefined topics or rules for this approach and different abstraction levels are possible for the issues dealt with during an Open Space Conference. As a result the outcome of this format is not predefined and dependent on the participating citizens and their preferences [20,26,27]. The format shows some similarities to a barcamp, which is an open event for knowledge sharing. The concrete timeline and content of a barcamp is developed at the beginning of the event together with all participants. Everyone is encouraged to contribute with a presentation or discussion on a certain topic [28].

The intention of a World Café is to create an informal atmosphere for conversations similar to visiting a café. This approach is intended to help groups of different sizes to “engage in constructive dialogue, to build personal relationships, and to foster collaborative learning” [29] (p. 84) by using seven design principles, including the encouragement of everyone to contribute to the discussion. Thereby, this format can support the initiation of public debates and strengthen social cohesion. Often, approaches like a World Café are used as a starting point for collecting and sharing knowledge in combination with other citizen participation methods [20].

Scenario Conferences or Workshops, Future Search Conferences and Future Workshops are approaches that are suitable for illustrating the future development of a city. The scenario technique is used to develop different scenarios of the future by designing and simulating several comprehensible pictures of the future [20]. The approach aims at forecasting long-term developments with regard to different framework conditions and to derive recommended actions based on these. Scenario Workshops are also suitable for finding a new way to organize and manage certain problems [24]. In Denmark, a Scenario Workshop was already used in 1991 for an urban ecology project, in which different scenarios described the potential life of a particular family in the future. The result was a national plan for urban ecology [24].

In a Future Search Conference, the participants develop measures and action plans for future projects. Within a predefined schedule, the main focus is not set on problems, but future development. This approach is often used for creating a new orientation of a municipality [20]. Participants discuss the past, the present, the future, as well as their common values and specify action plans [30]. Already in the context of the Local Agenda 21, Future Search Conferences were used each in a German and a British municipality to adopt the Local Agenda 21 process. Although a consensus vision was achieved in both municipalities, the quality of the results was deemed low, as most ideas were not translated into action. A major problem was thereby seen in a missing link to formal decision-making processes of the Council [31].

Future Workshops are especially used in the German-speaking countries and are composed by the three phases criticism (experiences of participants via brainstorming, identification of deficits), imagination (developing creative solutions without claim to reality) and realization (the best approaches are planned in more detail, search for collaborators and realization measures) [20,32]. The concept is based on the openness of the results and creativity. Similar to the Future Search Workshop and Scenario Conference, it is often used for developing a vision for the future of an organization or municipality. Scenario Conferences or Workshops, Future Search Conferences and Future Workshops have the potential to contribute to concrete solutions and hence are coined not only by an influential component, but also a consulting element.

In a Charrette (or Design Charrette), an interdisciplinary design team (including citizens and other interest groups) as well as experts come together for developing urban planning concepts. Mostly, these are concrete tasks of spatial development [20]. The idea of a Charrette has its origins in the town planning movement New Urbanism and is mostly organized in three phases: an information-sharing activity, the actual Charrette event and an implementation phase [33]. Practical implementations of this approach still have room for improvements [33], as a result municipalities should critically review the appropriateness of such processes.

The approach Planning for Real has the goal to improve the quality of life in certain spaces, e.g., public parks or districts. All interested citizens are invited to take part in the redesign process of their living space by contributing to the planning and implementation phases [20]. The name Planning for Real (http://www.planningforreal.org.uk/) is a registered trademark of an organization with the same name and its use needs their approval. Techniques offered by the organization include 3D models and other planning and evaluation models which can be applied to specific design tasks. Many municipalities use the concept of Planning for Real to react to existing citizen initiatives who aim at changing certain aspects in their neighbourhood or region [20]. In order to identify the local needs and to support the redesign process this approach can be helpful.

The methods Participatory Budgeting and Century Town Meeting address concrete topics and problems, which leads to a relatively high degree of decision-making power of the citizens. In a 21st Century Town Meeting, which is constructed for a large number of citizens, participants form groups, whereby each group performs face-to-face discussions with an independent moderator. This person collects the most important ideas and comments, while all results are subsequently collected centrally and sent to all groups for commenting and voting via keypad polling [20,34]. Developed by America Speaks, this approach is mainly used in the United States. Such 21st Century Town Meetings have been used for a wide range of topics at the national, regional and local scale, including Social Security reform and regional planning [34]. In practice, the realization is complex: “The 21st Century Town Meeting is more than a single event. It is an integrated process of citizen, stakeholder, and decision maker engagement over the course of many months” [34] (p. 51). This results in high costs and a tremendous (technical) effort to realize this method.

As the name suggests, a Participatory Budgeting aims at developing a municipal budgeting (or parts of it) while consulting also citizens. This process should be open for all interested persons and proceeds in three ideal-typical phases: information (presenting planned budget), consultation (citizens discuss aspects of the budget) and account (representatives of local politics explain which elements from the citizens were included, which not) [20]. Participatory Budgeting can take place offline, online or in the form of hybrid models [35]. Mostly, citizens only have a consultative role, but do not make actual decisions [20]. A similar approach is the idea of a Neighbourhood Fund. A determined budget is available, for which citizens can recommend projects for funding.

Applications of citizen participation formats with a focus on sustainability topics have been investigated in several countries. For example, Ref. [36] used three case studies to explore citizen involvement in environmental assessment in Canada. In these cases, citizens were able to determine agendas for monitoring and managing issues of environmental concern, to develop policies and regulatory recommendations and to implement management plans. The authors conclude that “increased citizen participation in follow-up activities such as monitoring could help to improve the quality and local relevance of environmental assessment, while at the same time advancing the process toward sustainability goals” [36] (p. 624). Besides, common obstacles like establishing credibility and receiving funding should not be neglected.

In Sweden, Ref. [37] investigated two case studies regarding local sustainability indicators. One of these cases, located in Stockholm, involved citizens in the process of formulating indicators for the local Agenda 21. The other case, located in Sundsvall, did not involve citizens in the process, but started an information campaign in this regard. This lack of citizen participation was deemed problematic. The authors argue that there is a gap between policy makers and citizens which is hard to bridge. Still, citizens should be involved more in local strategies on sustainable development, especially due to commitments to further democratisation in the municipalities [37].

Abel and Stephan [38] analyzed 16 local programs in the United States with an environmental focus and citizen participation elements of the organization Renew America. They used qualitative interviews to investigate, inter alia, the role of citizens in these programs. Most participants in these processes were citizens who have already been active before. In addition, only a few cases of citizen participation led to an actual influence on decision-making. The authors conclude that several obstacles of citizen participation in environmental decision-making have to be overcome in order to be successful [38].

One main challenge of municipalities is to develop a framework for meaningful local participation in the context of sustainability [17]. Therefore, we develop a model for demonstrating further possibilities to include citizen participation formats for adopting local sustainable development strategies. More specifically, we aim at answering the following research questions:

- RQ 1a.

- What citizen participation formats are currently being used for adopting local sustainable development strategies?

- RQ 1b.

- During which phases of adopting a local sustainable development strategy are citizen participation formats currently being applied?

- RQ 2a.

- What citizen participation formats are possible for adopting local sustainable development strategies?

- RQ 2b.

- During which phases of adopting a local sustainable development strategy are citizen participation formats possible?

- RQ 2c.

- To what extend are citizens able to contribute to decision-making when participating in the adoption process of sustainable development strategies?

The first part of our analysis concentrates on the application of citizen participation formats and important lessons learned from the pilot project (RQ 1). As participation is a crucial part of the SDGs, RQ 1 assesses the current status of German municipalities and their application of citizen participation formats for sustainable development strategies. With the second part of our analysis (RQ 2), we intend to go beyond the current status and to present a model that systematically demonstrates potential formats, phases, and the specific decision-making power of participating citizens.

3. Global Sustainable Municipalities North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany

In Germany, the federal government adopted its first national sustainable development strategy in 2002. Since then, the strategy is regularly revised, due to constantly changing conditions and requirements. In 2017, the federal government adopted “the most extensive enhancement of the Strategy” and also embedded the SDGs in the framework [39] (p. 2). Furthermore, the importance of citizen participation for sustainable development is emphasised in the strategy.

The administrative division of Germany is coined by federalism. The central government and the 16 states have different tasks and authorities. Most states consist of counties (districts and district-free cities). Districts are further subdivided into municipalities, whereby cities are municipalities with city rights. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany (https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_gg/) empowers local governments with the autonomous regulation of local affairs and requires them to fulfill their own administrative tasks [40]. Because of its limited size, municipalities are not always able to solve all the tasks of the local community by themselves and can be supported by the corresponding district. In contrast, some tasks are subject to the local self-government of a municipality and the state should not interfere in these, which is covered by the principle of subsidiarity. As local governments are a matter of the corresponding state, each with its own local government legislation [41], it is important to consider the specific state and its regulations.

The federal state North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) adopted its first sustainable development strategy in 2016 and was the first German state that defined and explicitly formulated its contribution to the Agenda 2030 and the SDGs. Beyond that, the design of the sustainable development strategy was coined by broad participation opportunities of science, economy and civil society, as well as the state’s municipalities [42]. By referring to SDG 11, the state government of North Rhine-Westphalia also emphasizes the importance to implement a sustainability management at the local level [43]. Similarly, the Association of German Cities [44] recommended cities to commit themselves to the SDGs. Several German cities acknowledge the importance of public awareness and engagement in relation to the SDGs. They use citizen participation formats for disseminating information on sustainable development and the SDGs and thus raise awareness on these topics [45]. Generally, efforts of giving citizens more say in local politics started in the 1990s in all German states, whereas the degree of change in the local government institution was among the greatest in North Rhine-Westphalia [41].

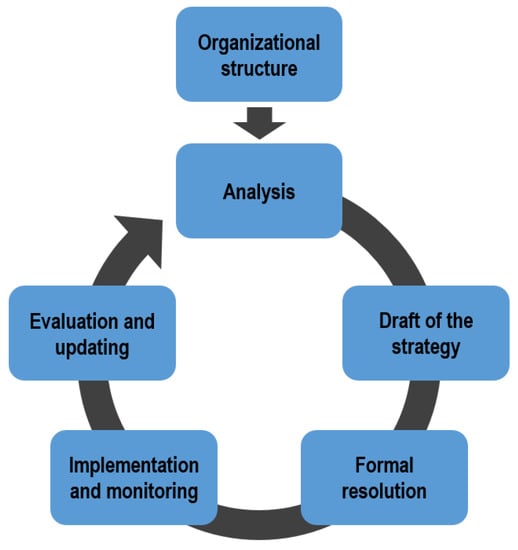

The pilot project “Global Sustainable Municipalities NRW” aims at supporting selected municipalities in North Rhine-Westphalia to systematically develop their sustainable development strategy. The working group “LAG 21 NRW” advises municipalities in developing sustainability management systems by using a participative approach. By bringing together the participating municipalities, an exchange of ideas and experiences is initiated. We concentrated on this project, as it provides a prototypical, systematic approach to design and implement a local sustainable development strategy. In the project, the journey of building a sustainable development strategy is regarded as an ideal-typical continuous improvement process (CIP), which is depicted in Figure 1 [46].

Figure 1.

Ideal-typical process of adopting a sustainable development strategy (adapted from [46]).

An organizational structure with predefined roles and responsibilities forms the starting point of the process. Based on an initial assessment of the municipality’s current state—by both quantitative indicators and qualitative evaluations—a participating community in the project creates a first draft of the strategy, which entails a mission statement, thematic guidelines, strategic and operative goals, measures, as well as planned resources. This is followed by the formulation of the strategy and its formal resolution by the municipality’s council. After the implementation of the strategy via concrete projects, a further evaluation of the strategy and its efforts takes place. This process is consistent with the strategy’s purpose of serving as a structure for decision-making and also offering specific goals, indicators and actions [7].

4. Materials and Methods

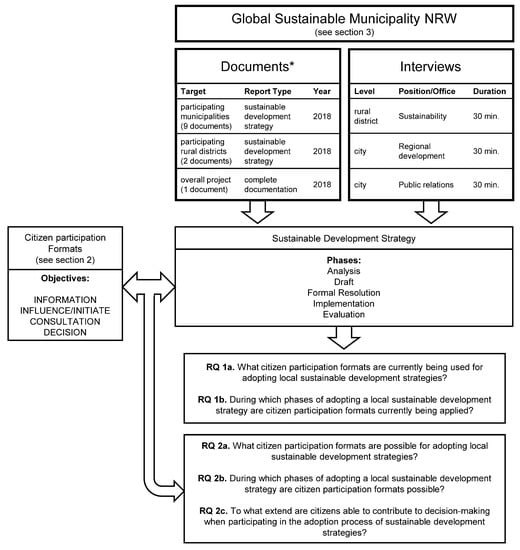

The analysis in this paper is divided into two parts. The first part reports on a case study of the German pilot project “Global Sustainable Municipalities NRW” described in the previous section with the goal to assess the current status of the use of citizen participation formats for adopting local sustainable development strategies (RQ 1). For the qualitative analysis of this project we rely on (1) published reports of the participating municipalities as well as (2) qualitative interviews with responsible persons of the project. Figure 2 summarizes the types of sources used for the analysis. Each participating city or district in the pilot project had to document their path towards the sustainable development strategy. A rough structure for this report was given by the project lead (LAG 21). It entailed a description of the corresponding municipality, information on involved stakeholders, details about each phase of the adoption process of the strategy (Figure 1) and the sustainable development strategy itself with the defined goals, measures and indicators. Nine of the analyzed strategies were from municipalities, and two from districts. In addition, a complete documentation of the overall project is available. The documents were read by the authors and each reference on citizen participation, discussed topics and other aspects like knowledge sharing or communication modes were marked. In a second step, we reached out to the responsible contact persons for these sustainable development strategies, in order to learn more from their experiences and challenges with citizen participation formats during the design process of the sustainable development strategy. We conducted interviews via telephone with three responsible persons from two municipalities and one district, for which we used a semi-structured questionnaire (see Appendix A). The interviews took place in October, 2019, each of which lasted about 30 min.

Figure 2.

Materials used for the analysis.

The second part of the analysis goes beyond assessing the current status and intends to develop a model of citizen participation formats in local sustainable development strategies, aiming at demonstrating general possibilities to include citizen participation formats in the process of adopting a local sustainable development strategy (RQ 2). In order to develop the model, we used qualitative content analysis [47,48] using the software ATLAS.ti (https://atlasti.com/de/). We used existing literature on citizen participation formats (Section 2) to develop the codes by analysing goals, objectives, requirements, possible topics and stakeholder involvement. Subsequently, we used these codes on the documents described in the first part of the analysis (sustainable development strategies) and coded the different phases based on the ideal-typical CIP (Figure 1) towards a sustainable development strategy with the help of the codes developed from the participation formats.

5. Results

5.1. The Role of Citizen Participation for German Local Sustainable Development Strategies

The municipalities and districts that participated in the project “Global Sustainable Municipalities NRW” are coordinated in similar organizational structures, but with variations considering the concrete realization of this structure. The organizational structure forms the basis for the analysis phase and all subsequent stages (Figure 1). The project required a threefold division into an organization team (1–2 persons from public administration being primary responsible), a core team (5–8 persons from different municipal offices) and a coordinating group (15–20 persons from economy, science, politics, public administration and civil society) [46]. The organization team of six municipalities and districts consisted of administrative staff of a department of environment and sustainability or similar. Other departments that were represented in the organization teams were planning, building and housing, urban development, finance, public relations, as well as social work. Table 2 summarizes the organizational structure, knowledge sharing, citizen participation approaches as well as challenges and prerequisites resulting of the project “Global Sustainable Municipalities NRW”.

Table 2.

Citizen participation in the pilot project “Global Sustainable Municipalities North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW)”.

In contrast to the organization team, the coordinating groups consisted of a larger selection of representatives. For ten municipalities and districts, reference was made to civil society as an integral part of the coordinating group. However, in most cases, these participants of civil society took part in the process of developing the sustainable development strategy in their function as representatives of associations and organizations. One interview revealed that the corresponding municipality acknowledged the knowledge of experts and committed citizens as essential for the concrete topics of a sustainable development strategy and thus did not include citizens in a broader and more open form of participation for drafting the strategy. The same municipality also only informed the citizens on the sustainable development strategy after formally deciding on it.

In contrast, other municipalities informed civil society already in the early stages of adopting the sustainable development strategy, e.g., via the official website of the city or social media channels. For example, another interviewee reported about an early involvement of the broad public during a citizen workshop. Information was shared on the purpose of the strategy and based on these citizens were able to co-decide on the prioritized action fields for the draft. The participants were split into four groups and discussed pre-identified strengths and weaknesses of the municipality. The overall results were collected and shared with all participants. With the help of a questionnaire, the participants were then asked to rate twelve thematic fields due to their relevance for the sustainable development strategy. The five topics with the highest rating formed the basis for the strategy. In addition, the municipality invited children and adolescents to an event in order to discuss concrete measures embedded in the draft of the strategy. Two further municipalities also invited interested citizens to sustainability conferences in the early stage of drafting the sustainable development strategy. For one of these, the main goal was to share information on the current status of the strategy and to define preliminary measures for the draft. Several organisations and associations were present in order to provide necessary background information regarding sustainability topics. The other municipality organized two conferences, one for including the civil society’s ideas into the mission statement; the other for presenting the preliminary draft and to develop concrete measures and projects.

Nine municipalities included citizen participation as a goal itself into their sustainable development strategy and plan to use deliberative formats for implementing the strategy. The involvement ranges from concrete plans to develop the municipal budget by including participatory methods to the more general goal of producing guidelines for citizen participation in the municipality. The interviews further revealed that the implementation phase was in particular deemed relevant for citizen participation.

A special role is taken by the two participating districts in the project. One interviewee emphasized that the districts are not as close to the citizens as cities, hence citizen participation implies different challenges for these. However, the district can act as an example for the municipalities who can adopt the strategy on their own and adjust it to local circumstances. The interviewee from the district indicated that some municipalities are already adapting their strategy or even take the district as an example by taking part in the second round of the project “Global Sustainable Municipalities NRW”. The other district included several citizen participation formats for evaluating their current sustainable development strategy and creating an updated version. For this purpose, the district used online surveys, expert discussions as well as Future Workshops and an expert conference on mobility. In addition, the district planned to develop an online presence, aiming at enabling a facilitated information and communication process with regard to monitoring sustainable development.

Besides the chances of including citizen participation formats, some challenges have to be considered. The interviews found a lack of personnel and a limited budget as the main challenges with regard to systematically involve citizens into the decision-making process of the sustainable development strategy.

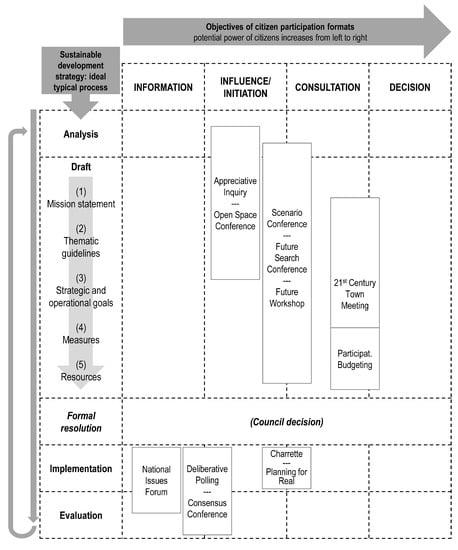

5.2. A Model of Citizen Participation Formats for Building Local Sustainability Strategies

Figure 3 summarizes our model of citizen participation formats for adopting a local sustainable development strategy. The participation formats are categorized due to their potential of creating added value in the ideal-typical steps of developing and implementing a local sustainable development strategy (see Figure 1). Furthermore, the figure entails the four objectives of the participation formats (see Table 1) and thus displays the citizens’ potential decision-making power during the process. In the following, the potential use of the presented citizen participation formats are described with regard to different phases in the process of building a sustainable development strategy.

Figure 3.

Model of citizen participation formats in different phases of adopting a local sustainable development strategy.

5.2.1. Analysis and Draft

The analysis phase is intended to assess the current status of a municipality in the matter of sustainable development. For the quantitative analysis a municipality can rely on indicators and statistics. In contrast, the qualitative analysis includes the gathering of existing local activities and projects, strategies and concepts, as well as political resolutions. The results of the quantitative and qualitative assessment of the current state can be used for performing a SWOT analysis in order to systematically define strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats of the municipalities efforts towards sustainable development.

Based on the analysis phase, the sustainable development strategy can be drafted. The strategy entails formulations on different abstraction levels. A mission statement depicts the municipality’s will to contribute to a sustainable development and defines the fundamental principles in doing so. Thematic guidelines describe the basic tendency of the strategy’s content and thematic priorities. Strategic goals define the municipality’s orientation regarding the thematic priorities over the long term, whereas operational goals are derived from these strategic goals and are formulated for the short to medium term. Measures designate responsible actors and ways how to achieve the goals. Resources refer to the measures and explicitly define financial and personnel means.

For the analysis and drafting phase, several citizen participation formats can be suitable. An Appreciative Inquiry can be used for creating a positive vision regarding a municipality’s sustainable development. This approach is in particular useful during the first stages of analyzing existing conditions and creating a mission statement for the sustainable development strategy. The concentration on existing strengths and the implied motivational character entails an influential element on the participating citizens and can initiate a debate on sustainable development. However, the decision-making power remains low in most cases. Similarly, Open Space Conferences can be useful in the early stages towards a sustainable development strategy, similar as an Appreciative Inquiry. In particular, the development of a mission statement could be enhanced with the participation of citizens and their ideas and preferences. The format is less useful for developing concrete goals and measures, as it cannot be predicted how the outcome will be shaped. Therefore, the decision-making power of this approach remains relatively low as well.

Scenario Conferences or Workshops, Future Search Conferences and Future Workshops are approaches that are suitable for illustrating the future development of a city and can hence especially serve for drafting a sustainable development strategy. A Scenario Workshop or Conference can be used for finding a new way to organize and manage problems in a new way and can hence be applied for organizing local sustainability activities in a novel way. Similarly, the approach of a Future Search Conference is often used for creating a new orientation of a municipality, which could be the strategy to become a sustainable community. Future Workshops are often used for developing a vision for the future of an organization or municipality, and hence can be an appropriate method for drafting a sustainable development strategy. Depending on the abstraction level of the given tasks, the above approaches can be applied to different levels of drafting a sustainable development strategy: from developing a mission statement, to formulating strategic and operational goals and for defining concrete measures and resources. However, for applying these methods to the more concrete elements of the draft (operational goals, measures and resources) different participant groups may have to be recruited than for the more abstract concepts: particular experts and interest groups are involved in these concrete measures and resources and assessing the suitability of these has to be ensured.

The methods 21st Century Town Meeting and Participatory Budgeting address more concrete topics and problems, which leads to a relatively high degree of decision-making power of participating citizens. Theoretically, a 21st Century Town Meeting can support the whole process of drafting a sustainable development strategy and may ensure the participation of a large amount of citizens. In practice, this approach implies high efforts and costs, and endures for a relatively long time span. Hence, many municipalities may not be able to provide the necessary prerequisites for realizing this method. Consulting citizens for planning the resources of a sustainable development strategy can be realized by variations of Participatory Budgeting.

5.2.2. Implementation and Evaluation

The formal resolution of a sustainable development strategy by a council decision serves its political legitimization. After the formal resolution, a municipality has to ensure the implementation of the corresponding goals and targets within different fields of municipal development. The implementation phase is followed by a broad evaluation of the strategy’s effects. It is intended to analyse causes for success or failure of the implemented program and serves the update of the strategy. Often, the first step is to inform the broad public about the adoption of the strategy. A National Issues Forum can be used to distribute information on the adopted strategy. The objective of this approach is informing citizens, hence it does not lead to actual decision-making, but aims at enabling citizens to use and adopt democratic skills by discussing predefined topics. If citizen participation and the strengthening of democratic skills itself is among the goals of the sustainability strategy, a National Issues Forum could also be used as a concrete implementation of this goal. Partly, the format can also be used to gather feedback on the implementation of the sustainable development strategy which can serve as a starting point for the evaluation phase.

The process of a Deliberative Polling might also be used for assessing citizens’ view on concrete topics and issues of a sustainable developing strategy, and to inform about the strategy in depth. The approach entails an information event which can be used for distributing information on the adopted sustainable development strategy and for giving the opportunity to discuss the embedded topics and issues with experts and politicians. As a large amount of randomly chosen citizens can take part in these events, a broad range of feedback can be gathered on the strategy. However, the decision-making power of participating citizens remains low, as the priority lies in information-sharing. A Consensus Conference aims at bringing science and practice together, mainly regarding issues of technology assessment, but also social or economic topics. The role of technology and digitization is a major issue for sustainable development, hence, a Consensus Conference can be used to discuss the application of such technology as an implementation issue of the sustainable development strategy. The influence of citizens on decision-making is of an indirect nature, as the discussions can help politicians to obtain new perspectives on concerns and opportunities regarding certain technologies.

When a sustainable development strategy entails concrete planning concepts, a Design Charrette can enhance the implementation process of the strategy. An interdisciplinary design team consisting of experts and citizens comes together for developing urban planning concepts, which can arise out of the sustainable development strategy. The decision-making power of individual participants is relatively high as the ideas developed during the design process may directly flow into the actual implementation. Similarly, the approach Planning for Real can lead to actual implementations and thus contribute to the decision-making power of the involved citizens in the form of consultation. All interested citizens can take part in the redesigning process of their living space, which can be among the goals of the sustainable development strategy.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

In this paper, we analyzed the use of citizen participation approaches for adopting local sustainable development strategies. The analysis is split into two parts. First, we concentrated on the pilot project “Global Sustainable Municipalities NRW” as a case study. We could detect several approaches to include citizen participation formats into the different phases of adopting a local sustainable development strategy. Most approaches aim at sharing information on the sustainable development strategy with the broad public. To some extend participating citizens are invited to share their ideas and visions in order to include these ideas into the mission statement or measures of the draft. Most municipalities include citizen participation as a goal itself into their sustainable development strategy. In this regard, the establishment of strategic guidelines for participation opportunities is predominant. This is in line with SDG 16 and its target 16.7 to ensure inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making at all levels [14]. The involvement of citizen participation as a goal of the sustainable development strategy shows that municipalities are aware of the significance of including civil society into decision-making. On the other hand, the goal to establish strategic guidelines for citizen participation also shows that there is a demand for systematic overviews on different participation formats.

In the second part of the analysis we developed a general model for citizen participation for adopting a sustainable development strategy which entails possible participation formats for each of the phases. We aimed at analyzing the concrete phases during which the participation methods can be applied. With the presented model, we demonstrated possibilities to include citizen participation methods in the whole process of drafting and implementing local sustainable development strategies. We also intended to assess the decision-making power of citizens participating in the potential formats. It becomes apparent that different participation models can serve different purposes and are coined by diverse objectives. This results in varying potential of decision-making power on the part of the participating citizens. While open and abstract formats without predefined outcomes, like Open Space Conferences, Appreciative Inquiries, Scenario Conferences, Future Conferences and Future Workshops can be useful in the early stages towards a sustainable development strategy and support in creating a vision for a city or municipality, events like 21st Century Meetings or Participatory Budgeting can address more concrete issues like measures or resources of a strategy. Concurrently, these methods represent the highest potential decision-making power of citizens. For implementing the strategy, formats like a National Issues Forum, as well as a Design Charrette or Planning for Real can be appropriate, whereas the two latter represent more specific design problems, that can lead to a higher degree of decision-making power of the participating citizens. Deliberative Polling and Consensus Conferences can be appropriate during both implementing and evaluating an existing strategy. Depending on the defined topics, goals and measures in a sustainable development strategy, further participation approaches are suitable for the implementing process. Especially when citizen participation itself is a goal in the strategy, different additional approaches are conceivable.

Although the described model and the listed participation formats may not be exhaustive, it gives a first overview on differences among the approaches and the corresponding appropriateness for the several phases, as well as the respective decision-making power. The goal of this study was not to work out challenges, terms and conditions for citizen participation in general, though these issues might be mentioned marginally, as they naturally occur when discussing participation approaches. For example, in most formats the question arises whether a true representation of the public voice is possible. For deeper discussions of advantages and disadvantages of citizen participation formats, we refer to the relevant literature, for example [10,12,15,16,17,19,20]. We also did not discuss costs and other prerequisites like the length of the different participation methods, nor did we include a deeper discussion of the selection process of the participants in the considerations. In practice, a municipality that wants to design its sustainable development strategy by including citizen participation formats, has to review existing methods according to local circumstances. The model can serve as a starting point for doing so. Furthermore, the model does not intend to propose the use of citizen participation in each phase of drafting and implementing a local sustainable development strategy, but rather suggests possibilities that provide a first orientation. It is also possible to combine several participation methods with each other and to adapt the approaches to one’s own needs. Often, approaches like a World Café are used as a starting point for collecting and sharing knowledge in combination with other citizen participation methods [20]. On the part of the analyzed municipalities, existing challenges are a limited budget or a lack of personnel for the organization of citizen participation approaches. This limitation has to be considered, when planning a sustainable development strategy by including participatory formats.

The proposed model relies on an ideal-typical CIP as proposed in the pilot project “Global Sustainable Municipalities NRW”, but can be transferred to other communities and cities around the world, as the reviewed citizen participation methods are used globally. The model can help municipalities to get an orientation on possible formats and the corresponding level of decision-making. The concrete implementation is yet dependent on national, regional and local prerequisites. The model could also be used at the regional level, but our results showed that different challenges have to be considered, as the citizens are present at the local level. A municipality does not necessarily have to adopt the ideal typical process of developing a sustainable development strategy (Figure 1) one-to-one. Nonetheless, it helps to strategically plan the adoption of the strategy. In the future, it would be interesting to explicitly evaluate the use of the proposed approaches of citizen participation for drafting and implementing local sustainable development strategies. Furthermore, a comparison of the presented results with other regional or national strategies would add additional value. In particular, assessing the participating citizens’ views with regard to the perceived benefits and drawbacks is of importance to fully understand the success of the applied formats as well as the recognized level of decision-making power. Similarly, analyzing the concrete outcome of participation formats with regard to local sustainable development strategies is an important issue. For example, the following questions arise: What kind of documentation is available from the participation events? Do the results of the events translate into concrete actions? The proposed model in this article can be a starting point for systematically analysing these questions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.; methodology, C.M.; formal analysis, C.M.; investigation, C.M. and A.M.; data curation, C.M. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.; writing—review and editing, C.M. and A.M.; visualization, C.M.; project administration, C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our interview partners for providing valuable insights into their experience with the respective sustainable development strategies and citizen participation. We acknowledge the support for publishing open access by the Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| CIP | Continual Improvement Process |

| NRW | North Rhine-Westphalia |

Appendix A. Interview Questions

Appendix A.1. Definition and Thematic Foci

- What do you understand by a local sustainable development strategy?

- What do you understand by a participative development of a local sustainable development strategy?

- Who should be involved in participation processes?

Appendix A.2. Implementation in the Corresponding Municipality (Flow of Knowledge and Added Value)

- How does your municipality plan and implement the sustainable development strategy?

- (a)

- How many persons are responsible for developing the strategy?

- (b)

- Are the responsible persons from public administration belonging to a specific department?

- What actors are included in the process of developing the sustainable development strategy apart from public administration?

- Is your municipality using citizen participation formats within the framework of the sustainable development strategy?

- (a)

- In which phases of implementing the sustainable development strategy do you use participative elements?

- (b)

- Who is invited to participate? Which criteria are used to select the participants?

- (c)

- What concrete channels and methods are used for citizen participation formats?

- (d)

- To what extend does the outcome of participation formats feed into the sustainable development strategy?

- Where do you see potential for improvement in your current approach on citizen participation and the development of the sustainable development strategy?

Appendix A.3. Cooperation with other Municipalities

- Can other municipalities benefit from your approach?

- (a)

- How do you cooperate with other municipalities?

- (b)

- How do you share experience and outcomes?

Appendix A.4. Further Suggestions

- Do you have further topics or suggestions not covered by the above questions?

References

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 5 September 2019).

- WCED. Report on the World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 1–247.

- Quental, N.; Lourenço, J.M.; Da Silva, F.N. Sustainable development policy: Goals, targets and political cycles. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Klopp, J.M.; Petretta, D.L. The urban sustainable development goal: Indicators, complexity and the politics of measuring cities. Cities 2017, 63, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The New Urban Agenda; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Meadowcroft, J. National sustainable development strategies: Features, challenges and reflexivity. Eur. Environ. 2007, 17, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, J.; Mellouli, S. Winning the SDG battle in cities: How an integrated information ecosystem can contribute to the achievement of the 2030 sustainable development goals. Inf. Syst. J. 2017, 27, 427–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibri, S.E.; Krogstie, J. Smart sustainable cities of the future: An extensive interdisciplinary literature review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 31, 183–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, P. Building open government. Gov. Inf. Q. 2010, 27, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, O.; Stoett, P. Citizen Participation in UN Sustainable Development Goals. Glob. Gov. 2016, 22, 555–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J.; Wheeler, J. What community development and citizen participation should contribute to the new global framework for sustainable development. Community Dev. J. 2015, 50, 552–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriskandarajah, D. A People’s Agenda: Citizen Participation and the SDGs. In From Summits to Solutions: Innovations in Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals; Desai, R., Kato, H., Kharas, H., McArthur, J., Eds.; Innovations in Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals, Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 302–317. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Goal 16: Promote Just, Peaceful and Inclusive Societies. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/peace-justice/ (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Irving, R.A.; Stransbury, J. Citizen Participation in Decision Making: Is It Worth the Effort? Public Adm. Rev. 2004, 64, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, C.V.; Wang, X.H. Sustainable Development Governance: Citizen Participation and Support Networks in Local Sustainability Initiatives. Public Works Manag. Policy 2012, 17, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadowcroft, J. Participation and Sustainable Development: Modes of Citizen, Community and Organisational Involvement. In Governance for Sustainable Development: The Challenge of Adapting Form to Function; Lafferty, W., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenhan, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 162–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder Of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouki, A.; Mellouli, S.; Daniel, S. Towards a context-based citizen participation approach: A literature review of citizen participation issues and a conceptual framework. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, New Delhi, India, 7–9 March 2017; pp. 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanz, P.; Fritsche, M. Handbuch Bürgerbeteiligung; Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung: Bonn, Germany, 2012; Volume 1200, p. 144. [Google Scholar]

- Gastil, J.; Dillard, J.P. Increasing Political Sophistication Through Public Deliberation. Political Commun. 1999, 16, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodin, R.E.; Dryzek, J.S. Deliberative Impacts: The Macro-Political Uptake of Mini-Publics. Politics Soc. 2006, 34, 219–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, H.E.; Fishkin, J.S.; Luskin, R.C. Informed Public Opinion about Foreign Policy: The Uses of Deliberative Polling. Brook. Rev. 2003, 21, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, I.E.; Jaeger, B. Scenario workshops and consensus conferences: Towards more democratic decision-making. Sci. Public Policy 1999, 26, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Emerick, N. Sustainable Cleveland 2019: Designing a Green Economic Future Using the Appreciative Inquiry Summit Process. Public Works Manag. Policy 2012, 17, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.M.; McCormick, M.T.; Pearce, D.S. Combining Future Search and Open Space to Address Special Situations. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2005, 41, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrington, N. Open Space Conferences: A new way of working. Manag. Educ. 2006, 20, 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennerlein, S.; Gutounig, R.; Kraker, P.; Kaiser, R.; Rauter, R.; Ausserhofer, J. Knowledge strategies in organisations: A case for the barcamp format. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Knowledge Management, ECKM; University of Udine: Udine, Italy, 2015; pp. 222–230. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, S.; Brown, J. The world café in Singapore: Creating a learning culture through dialogue. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2005, 41, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisbord, M.R.; Janoff, S. Future search: Finding Common Ground in Organizations and Communities. Syst. Pract. 1996, 9, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oels, A. The Power of Visioning: The Contribution of Future Search Conferences to Decision-Making in Local Agenda 21 Processes. In Public Participation and Better Environmental Decisions: The Promise and Limits of Participatory Processes for the Quality of Environmentally Related Decision-making; Coenen, F.H.J.M., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müllert, N.R. Zukunftswerkstätten. In Zukunftsforschung und Zukunftsgestaltung: Beiträge aus Wissenschaft und Praxis; Popp, R., Schüll, E., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, S.; Thompson-Fawcett, M. Public Participation and New Urbanism: A Conflicting Agenda? Plan. Theory Pract. 2007, 8, 449–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukensmeyer, C.J.; Brigham, S. Taking Democracy to Scale: Large Scale Interventions—For Citizens. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2005, 41, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkude, C.G.; Pérez-Espés, C.; Wimmer, M.A. Participatory budgeting: A framework to analyze the value-add of citizen participation. In Proceedings of the Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2014; pp. 2054–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsberger, C.A.; Gibson, R.B.; Wismer, S.K. Citizen involvement in sustainability-centred environmental assessment follow-up. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2005, 25, 609–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckerberg, K.; Mineur, E. The use of local sustainability indicators: Case studies in two Swedish municipalities. Local Environ. 2003, 8, 591–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, T.D.; Stephan, M. The Limits of Civic Environmentalism. Am. Behav. Sci. 2000, 44, 614–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German Federal Government. German Sustainable Development Strategy (Summary). Available online: https://www.bundesregierung.de/Content/EN/StatischeSeiten/Schwerpunkte/Nachhaltigkeit/Anlagen/2017-04-12-kurzpapier-n-en.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=7 (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Gabriel, O.W.; Ahlstih, K.; Brettschneider, F.; Kunz, F. Transformations in Policy Preferences of Local Officials. In The New Political Culture; Clark, T.N., Hoffmann-Martinot, V., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA; Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 219–234. [Google Scholar]

- Vetter, A. Citizens versus parties: Explaining institutional change in German local government, 1989-2008. Local Gov. Stud. 2009, 35, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunkhorst, S.; Obenland, W. SDGs für die Bundesländer. Global Policy Forum 2017, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Die Landesregierung Nordrhein-Westfalen. Nachhaltigkeitsstrategie für Nordrhein-Westfalen. Available online: https://www.nachhaltigkeit.nrw.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Nachhaltigkeitsstrategie_PDFs/NRW_Nachhaltigkeitsstrategie_Broschuere_DE_Online_Version_22032017.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Deutscher Städtetag. 2030-Agenda für Nachhaltige Entwicklung: Nachhaltigkeit auf kommunaler Ebene gestalten. Available online: http://www.staedtetag.de/fachinformationen/staedtetag/075357/index.html (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Meschede, C. Information dissemination related to the Sustainable Development Goals on German local governmental websites. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 71, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LAG 21 NRW; SKEW. Global Nachhaltige Kommune NRW. Gesamtdokumentation; LAG 21 NRW and SKEW: Bonn, Germany, 2018; p. 111. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken, 12th ed.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany; Basel, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis. An Introduction to Its Methodology, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).