The Traditional Enjoyment of Noted Natural Places in Urban South Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methods

2.1. The Extraction of Sites to Be Analyzed (Noted Natural Places)

2.2. Analysis Methods

2.2.1. Analysis of Scenery Characteristics

2.2.2. Analysis of Supplementary Activities to Grasp Usage Characteristics

2.2.3. Distribution of Noted Natural Places and Analysis of Positioning Characteristics

3. Results

3.1. Activities in the Viewing of Noted Natural Places

3.1.1. Viewing Activities

3.1.2. Supplementary Activities

3.2. Types of Enjoyment in Noted Natural Places

4. Discussion: Relationship Between the Positioning, Scenic Structure, and Enjoyment of Noted Natural Places

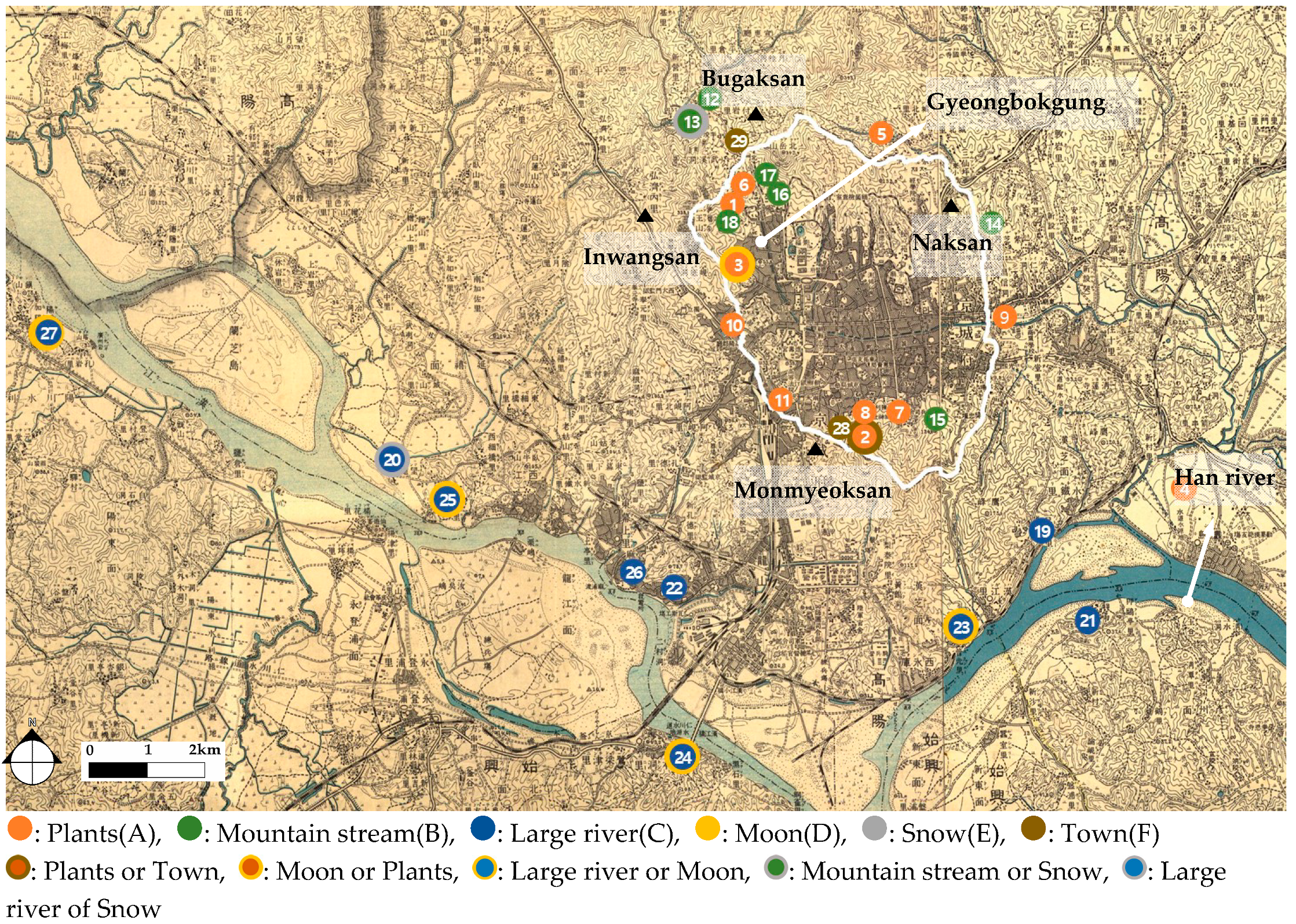

4.1. Distribution and Positioning of Noted Natural Places

4.2. Relationship Between the Positioning, Scenic Structure, and Enjoyment of Noted Natural Places

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- In this study, places considered as famous places in Hanyang were visited by numerous people to enjoy nature, go on excursions, experience leisure time, and play; places with exceptional scenery; and places that inspired poetry. These are referred to here as “noted natural places.”.

- Kuwano, S. Parks and communities in European civilization—A proposal for the growth of “citizens’ publicity” in Japan. Bull. Koriyama Women’s Univ. 2018, 54, 249–259. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, K.W. The Leisure and Outdoor Recreation Culture of Korea; Seoul National University Press: Seoul, Korea, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chae, J.H. Change of Pluralistic Value in Mt. Gwanak as Suburban Mountain: Interdisciplinary Doctoral Program in Landscape Architecture Major; Graduate School, Seoul National University: Seoul, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dastgerdi, A.S.; De Luca, G. Specifying the significance of historic sites in heritage planning. Conserv. Sci. Cult. Herit. 2018, 18, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshinaga, A. Urban Environment and Public Sphere—Implications for Environmental History Research. J. Public Aff. 2005, 2, 285–298. [Google Scholar]

- Grifoni, R.C.; D’Onofrio, R.; Sargolini, M. Quality of Life in Urban Landscapes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ono, S. City People’s Recreation in the Edo Period. Jpn. Inst. Landsc. Archit. 1990, 57, 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Taninaka, H. Fundamental Problems on the Planning of Suburban Recreational Woods. Jpn. Inst. Landsc. Archit. 1990, 53, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hanyu, F. A Study on the Formation and the Maturity of the Sights in Edo city—Through the analysis of the attraction and the special composition of the Sights. J. City Plan. Inst. Jpn. 2004, 39, 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuke, M. Style of Japan Observed in The Public Park a Transition from Edo Period; Hosei University: Tokyo, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.J. The Transitional Characteristics of Landscape & Attractions in Seoul, through Analysis of the Landscape Associated Texts; University of Seoul: Seoul, Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.W.; Lee, Y.H.; Kim, J.J. The Types and Characteristics of Natural Scenery in Landscape Painting during Joseon Dynasty. J. Korean For. Soc. 2014, 103, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H. Study on the Landscape Characteristics of Waterfront in Real Landscape Painting. Master’s Thesis, Dong-a University, Busan, Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.I.; Sung, J.S. A Study on Landscape Characteristics of Flower-viewing Sites through Historical Literatures in the Late Joseon Dynasty. J. Korean Inst. Tradit. Landsc. Archit. 2016, 34, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.H.; Son, Y.H.; Hwang, K.W. A Study on the Cultural Landscape around Lotus Ponds of Fortress Wall of Seoul through Old Writings in the Joseon Dynasty. J. Korean Inst. Tradit. Landsc. Archit. 2016, 34, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Kim, H.B.; Lee, S.H. The Comparative Study on the Landscape Attractions of Seoul in Joseon Dynasty: Focusing on the Eight Scenery Poems. True-View Landsc. Paint. Folk. Lit. Korea Res. Inst. Hum. Settl. 2014, 82, 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, K.H. Transition: Two Modes of Landscape Painting in Early Eighteenth-Century Korea. J. Art Hist. Vis. Cult. 2006, 5, 192–232. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, K.H. Late Joseon Pictures of Notable Sights of Hanyang and Eight Views of Hanyang Reassessed; Soongsil University: Seoul, Korea, 2012; Volume 10, pp. 147–194. [Google Scholar]

- Na, H.Y. A Study on the Hanyang Myung Seung Paintings; Ewha Womans University: Seoul, Korea, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.S. Seoul’s Scenic and Historic Places; The Seoul Special Municipal Historical Compilation Committee: Seoul, Korea, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Seoul City. The 600-Year History of Seoul Vol. 1, 2, and 3; The Seoul Special Municipal Historical Compilation Committee: Seoul, Korea, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, C.Y. Reviewing the noted places of the west village and a true-view landscape painting of late Joseong period. Inst. Seoul Stud. 2013, 50, 69–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korean Classics Comprehensive DB. Available online: http://db.itkc.or.kr/ (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Kim, S.H. A Study on the Placeness of Pavilion of the Han River in Seoul during Chosun Dynasty; Sangmyung University: Seoul, Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, S.Y. A Typology of Experiencing the Scenic Site during the Joseon Dynasty Era: A Case Study of Yeongseo Area; Graduate School of Korea National University of Education: Chungcheongbuk-do, Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, J.U. Interpreting Cultural Scenery in Hanson and the Surrounding Area as Expressed in the Realistic Landscape Paintings of Jeong Seon; Korea University: Seoul, Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kansong Art and Culture Foundation. Available online: http://kansong.org/ (accessed on 3 July 2019).

- Samseong Museum of Publishing. Available online: http://ssmop.org/ (accessed on 3 July 2019).

- Higuchi, T. The Visual and the Spatial Structure of Landscapes; Gihodo: Tokyo, Japan, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Seoul City. Seoul’s Mountains; The Seoul Special Municipal Historical Compilation Committee: Seoul, Korea, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, Y.S. The Spatial Structure of ‘Hanseongbu’ in Late Joseon Dynasty; Seoul National University: Seoul, Korea, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, M.S. Pattern Classification and Characteristics Concerning Landscape on Mountainas and Hills by Using a Landscape Picture—The Case of Seoul City. J. Korean Inst. Tradit. Landsc. Archit. 2001, 29, 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y.J.; Bae, M.K. Prospect Behavior in the Analysis of Kyumjae Chung Sun’s One Hundred Scenes from the Real Landscape Painting. J. Korean Inst. Landsc. Archit. 2002, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Encyclopedia of Korean Culture. Available online: http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/ (accessed on 3 July 2019).

- National Museum of Korea. Available online: http://www.museum.go.kr/ (accessed on 3 July 2019).

| Work Name | Period | Category | Document Characteristics | Number of Noted Places | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Album of Gyeonggyo myeongseung (京校名勝帖 上, 下) | 1740 | Paintings | Paintings depicting noted places around the Han River | 33 |

| 2 | Eight Sights of Yangcheon (陽川八景帖) | 1742 | Paintings | Paintings depicting noted places around Yangcheon | 8 |

| 3 | Eight Sights of Jangdong (壯洞八景帖1,2) | 1755 | Paintings | Paintings depicting noted places of Inwangsan and Bugakusan | 11 |

| 4 | Gukdo-palkyong (国都八詠) | c. 1800 | Poems | Poems with themes of typical noted places of Hanyang | 8 |

| 5 | Hangyeong-jiryak (漢京識略) | c. 1800 | Book of customs | Records of noted places in Hanyang | 19 |

| 6 | Kyungdo-japji (京都雜志) | c. 1800 | Book of customs | Records of people’s lifestyles and seasonal customs in Hanyang | 8 |

| 7 | Yeolyang–Seshigi (洌陽歳時記) | 1819 | Book of customs | Records of seasonal customs and annual events in Hanyang | 3 |

| 8 | Hanyang-ga (漢陽歌) | 1844 | Gasa Literature | Records of attractions, festivals, and daily life in Hanyang | 23 |

| 9 | Donggook–seshigi (東国歳時記) | 1849 | Book of customs | Records of seasonal customs and yearly events | 18 |

| 10 | Donggukmunheonbigo (東国輿地備考) | c. 1870 | Book of geography | Records of geographical facts and noted places, such as pavilions | 20 |

| a. Primary Natural Feature: Moon | b. Primary Natural Feature: Sand | c. Primary Natural Features: Peach, Willow |

|---|---|---|

|  |  |

| Soakru (小岳樓) Jeongseon (c. 1741), 「小岳候月」 | Soakru (小岳樓) Jeongseon (c. 1741), 「錦城平沙」 | Pilundae (弼雲臺) Im Deuk-myeong (c. 1786),「登高賞花」 |

| Category | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Position of Primary Natural Features | High | Name of the place, including, words such as “tower” or “pole”, indicating a high place. Descriptions of viewing the scenery including items such as “lookdown” or “a high place”. |

| Level | No description such as “look up”, “overlook“, or height | |

| Low | Descriptions of viewing the scenery, including items such as “look up”. | |

| Mixed | Descriptions of viewing the same scenery simultaneously, including items such as “lookdown” and “look up”. | |

| Distance from Viewpoint | Far | Descriptions related to open spatial features Descriptions of viewing the scenery, including items such as “far.”, “wide.”, “opened” |

| Middle | No description such as “far” or “near” | |

| Near | Descriptions of viewing the scenery, including items such as “near”, “narrow”, or ”closed” Detailed description about the object | |

| Mixed | Descriptions of “far” and “near” occurring together |

| Place Number | Place Name | Viewing Activity | Supplementary Activities | Position | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viewing Object | Viewing Method | Season | Category | Locations | ||||||

| Primary Natural Feature | Secondary Natural Feature | View Point | Distance | |||||||

| 1 | Sesimdae (洗心臺) | Plants (peach, willow) | Mountain, town | High | Middle, far | Spring | A1 | 3 | Exercise, food, cultural | High ground or plateau |

| 2 | Jamdoobong (蠶頭峰) | Plants (peach, willow) | Mountain, town | High | Middle, far | Spring | Cultural | High ground or plateau | ||

| 3 | Pilundae (弼雲臺) | Plants (peach, willow) | Mountain, town | High | Middle, far | Spring | Food, cultural | High ground or plateau | ||

| 4 | Salgoji Bridge (箭串 橋) | Plants (apricot, willow) | Mountain, stream | Level, high | Near, middle | Spring | A2-a | 2 | Food, cultural | River |

| 5 | Bukdun (北屯) | Plants (peach) | Mountain, stream | Level, high | Near, middle | Spring | Cultural | Valley | ||

| 6 | Cheongpunggye (淸風溪) | Plants (autumn foliage) | Mountain, stream | Level | Near | Autumn | A2-b | 3 | Food, cultural | Profound valley |

| 7 | Hujodang (後彫堂) | Plants (autumn foliage) | Mountain, stream | Level | Near | Autumn | Food, cultural | Profound valley | ||

| 8 | 雙檜亭 | Plants (autumn foliage) | Mountain, stream | Level | Near | Autumn | Food, cultural | Profound valley | ||

| 9 | Dongdaemun (興仁門) | Plants (lotus, willow) | Pond | Level | Near | Summer | A3 | 3 | Crafting, food, cultural | Plain |

| 10 | Cheonyunjeong (天然亭) | Plants (lotus, willow) | Pond | Level | Near | Summer | Food, cultural | Plain | ||

| 11 | Namji (南池) | Plants (lotus, willow) | Pond | Level | Near | Summer | Food, cultural | Plain | ||

| 12 | Tangchundae (蕩春臺) | Mountain stream | Stones | High | Middle | Summer | B1-a | 2 | Exercise, food, cultural | Valley |

| 13 | Saegumjeong (洗劍亭) | Mountain stream | Stones | High | Middle | Summer | Exercise, food, cultural | Valley | ||

| 14 | Hyeopganjeong (夾澗亭) | Mountain stream | Stones | Level, high | Near, middle | Summer | B1-b | 2 | Exercise, food, cultural | Valley |

| 15 | Cheonugak (泉雨閣) | Mountain stream | Stones | Level, high | Near, middle | Summer | Exercise, food, cultural | Valley | ||

| 16 | Dongrakjeong (獨樂亭) | Mountain stream | Stones | Level | Near | - | B1-c | 3 | Cultural, solitary play | Profound valley |

| 17 | Cheongsongdang (聽松堂) | Mountain stream | Stones | Level | Near | - | Cultural, solitary play | Profound valley | ||

| 18 | Chunghuigak (晴暉閣) | Mountain stream | Stones | Level | Near | - | Cultural, solitary play | Profound valley | ||

| 19 | Ipseokpo (立石浦) | Large river | rock | Level | Near, middle | - | C1 | 1 | Exercise, food | River |

| 20 | Yanghwajin (楊花津) | Large river | Mountain, rock, boat | Level | Far | - | C2-a | 1 | Unknown | Large river |

| 21 | Apgujeong (狎鷗亭) | Large river | Mountain, rock, boat | High | Middle, far | - | C2-b | 7 | Exercise, food, cultural | High ground or plateau |

| 22 | Eupcheongru (挹淸樓) | Large river | Mountain, rock, boat | High | Middle, far | - | Exercise, food, cultural | High ground or plateau | ||

| 23 | Jecheonjeong (濟川亭) | Large river | Mountain, rock, boat | High | Middle, far | - | Exercise, food, cultural | High ground or plateau | ||

| 24 | Wolpajeong (月波亭) | Large river | Mountain, rock, boat | High | Middle, far | - | Exercise, food, cultural | High ground or plateau | ||

| 25 | Mangwonjeong (望遠亭) | Large river | Mountain, rock, boat | High | Middle, far | - | Exercise, food, cultural | High ground or plateau | ||

| 26 | Damdamjeong (淡淡亭) | Large river | Mountain, rock, boat | High | Middle, far | - | Cultural | High ground or plateau | ||

| 27 | Soakru (小岳樓) | Large river | Mountain, rock, boat | High | Middle, far | - | Food, cultural, solitary play | High ground or plateau | ||

| 28 | Pilundae (弼雲臺) | Moon | Mountain | Low | Far | - | D1 | 1 | Food, cultural | High ground or plateau |

| 29 | Jecheonjeong (濟川亭) | Moon | Large river, mountain | Mixed | Mixed | - | D2 | 4 | Exercise, food, cultural | High ground or plateau |

| 30 | Wolpajeong (月波亭) | Moon | Large river, mountain | Mixed | Mixed | - | Exercise, food, cultural | High ground or plateau | ||

| 31 | Mangwonjeong (望遠亭) | Moon | Large river, mountain | Mixed | Mixed | - | Exercise, food, cultural | High ground or plateau | ||

| 32 | Soakru (小岳樓) | Moon | Large river, mountain | Mixed | Mixed | - | Food, cultural, solitary play | High ground or plateau | ||

| 33 | Yanghwajin (楊花津) | Snow | Mountain | Level | Middle, Far | - | E1 | 1 | Unknown | Large river |

| 34 | Saegumjeong (洗劍亭) | Snow (ice) | Stones | High | Middle | Winter | E2 | 1 | Exercise, food, cultural | Valley |

| 35 | Jamdoobong (蠶頭峰) | Town | Mountain | High | Far | - | F1 | 3 | Cultural | High ground or plateau |

| 36 | Chilsongjeong (七松亭) | Town | Mountain | High | Far | - | Unknown | High ground or plateau | ||

| 37 | Changuimun (彰義門) | Town | Mountain | High | Far | - | Unknown | High ground or plateau | ||

| Topography | Applicable Place | Type | Example | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plain |  | A3 |  1) 1) | |

| High ground or plateau | Mountain |  | A1 D1 F1 |  2) 2) |

| ||||

| Large river area |  | C2-b |  3) 3) | |

| Valley | Profound |  | A2-b |  4) 4) |

| B1-c | |||

| Other |  | A2-a B1-a E2 |  4) 4) | |

| B1-b | |||

| River |  | A2-a C1 | - | |

| Large River |  | C1 E1 | - | |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, E.; Shimomura, A.; Yamamoto, K.; Nakamura, K.W. The Traditional Enjoyment of Noted Natural Places in Urban South Korea. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3030092

Park E, Shimomura A, Yamamoto K, Nakamura KW. The Traditional Enjoyment of Noted Natural Places in Urban South Korea. Urban Science. 2019; 3(3):92. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3030092

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Eunbyul, Akio Shimomura, Kiyotatsu Yamamoto, and Kazuhiko W. Nakamura. 2019. "The Traditional Enjoyment of Noted Natural Places in Urban South Korea" Urban Science 3, no. 3: 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3030092

APA StylePark, E., Shimomura, A., Yamamoto, K., & Nakamura, K. W. (2019). The Traditional Enjoyment of Noted Natural Places in Urban South Korea. Urban Science, 3(3), 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3030092