City Data Plan: The Conceptualisation of a Policy Instrument for Data Governance in Smart Cities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- How to facilitate a sustainable redistribution of the benefits associated with the availability of an unprecedented among local stakeholders?

- How to frame the production and use of city data into a comprehensive vision of social and economic development for the city?

- Section 2 provides a short overview of the key topics and issues concerning the governance of data in smart city literature.

- Section 3 explains the methodological approach adopted for defining the City Data Plan through the theoretical analysis of the concepts describing corporate data governance plans and urban plans.

- Section 4 reports on the analytic process to conceptualise the City Data Plan.

- Section 6 describes three examples of urban applications of the City Data Plan in the specific context of the city of Milton Keynes (UK).

- Section 7 discusses potentialities, limitations and open challenges of this type of policy instruments respect to the constraints of the problem of the data governance in the city.

- Section 8 concludes the paper by highlighting the contribution of the work to the domain of urban planning research and practice.

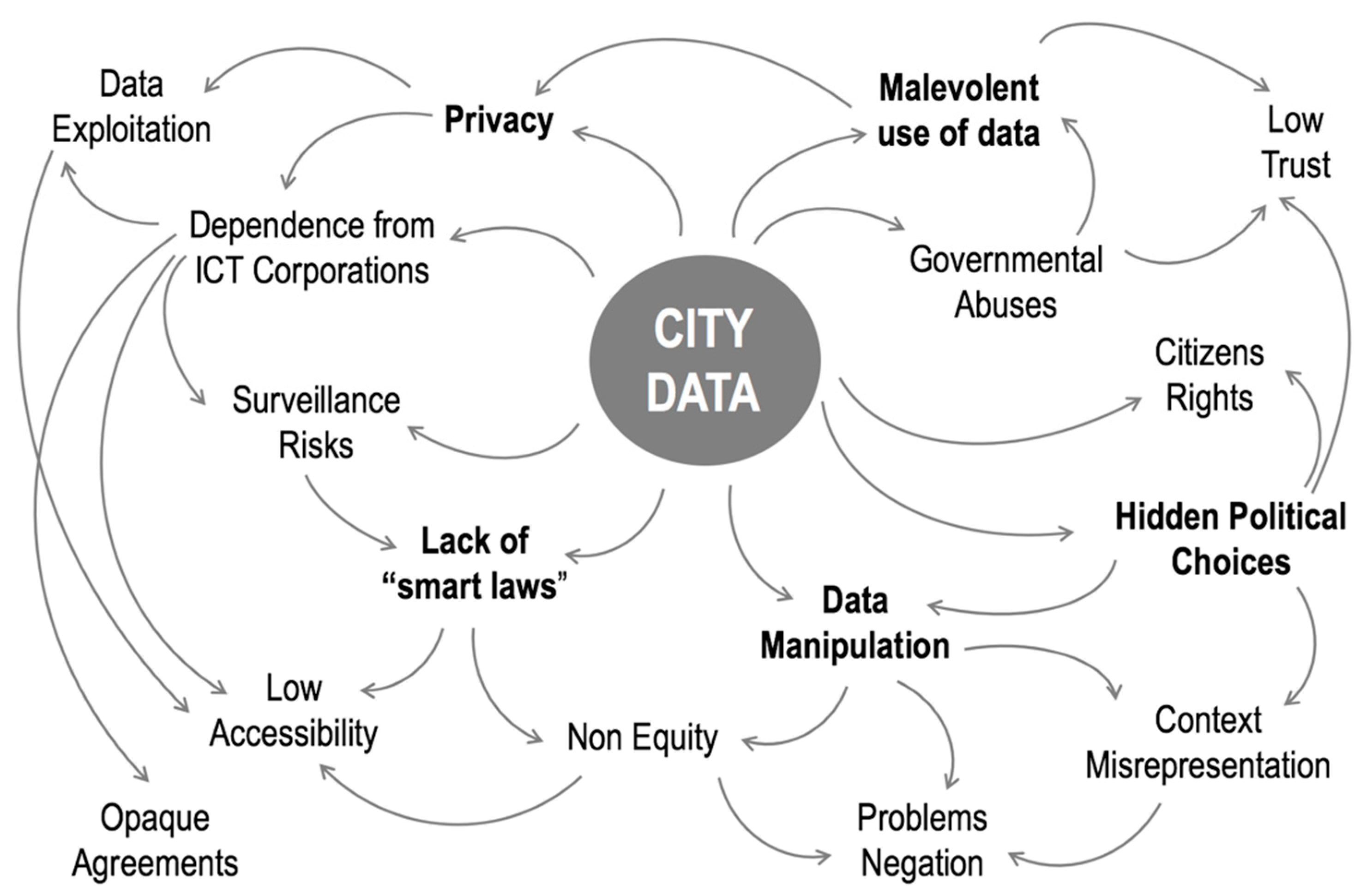

2. Related Works

- The manipulation of data

- The indiscriminate use of data to control social phenomena or groups

- The subjects from which data are collected (usually citizens and city services customers)

- The intended users of data (other organisations, public, private or non-profit)

- Knowledge professionals and media that communicate through data

- (a)

- Getting smart city technologies more familiar to the public through dissemination and public information activities

- (b)

- Enforcing the anonymisation of data and contrasting data crossing procedures for re-identification

- (c)

- Enhancing the transparency in the use of data for city operations by governmental authorities

- (d)

- Moving from data as objects to data as a “plus” of digital services through the “data featurization”.

- The type of normative and technological instruments to support the interdependent activities of the proposed institutional structures.

- The potential measures to deal with variable levels of commitment of politics and local actors to the continuous implementation of a common strategy for the production and use of city data.

- (1)

- Oriented to balance the power of data producers and primary users (technology providers and public authorities) respect to other actors involved in the city data ecosystem as data collectors, secondary users, data subjects (i.e., citizens, local communities, businesses, non-profit organisations)

- (2)

- Based on negotiation and consensus among city stakeholders on the contents of city data policies

- (3)

- Managed through transparent and explicit rules for the production and use of data that distinguish between legitimate and illegitimate uses of data and reveal the rationale of data-centred operations

- (4)

- Built to connect the production and use of city data to local needs for effectively exploiting data to address real problems

- (5)

- Reactive and responsive to the evolution of the city data ecosystem through flexible mechanisms that can be refactored over time to achieve new goals, include new actors, integrate new resources.

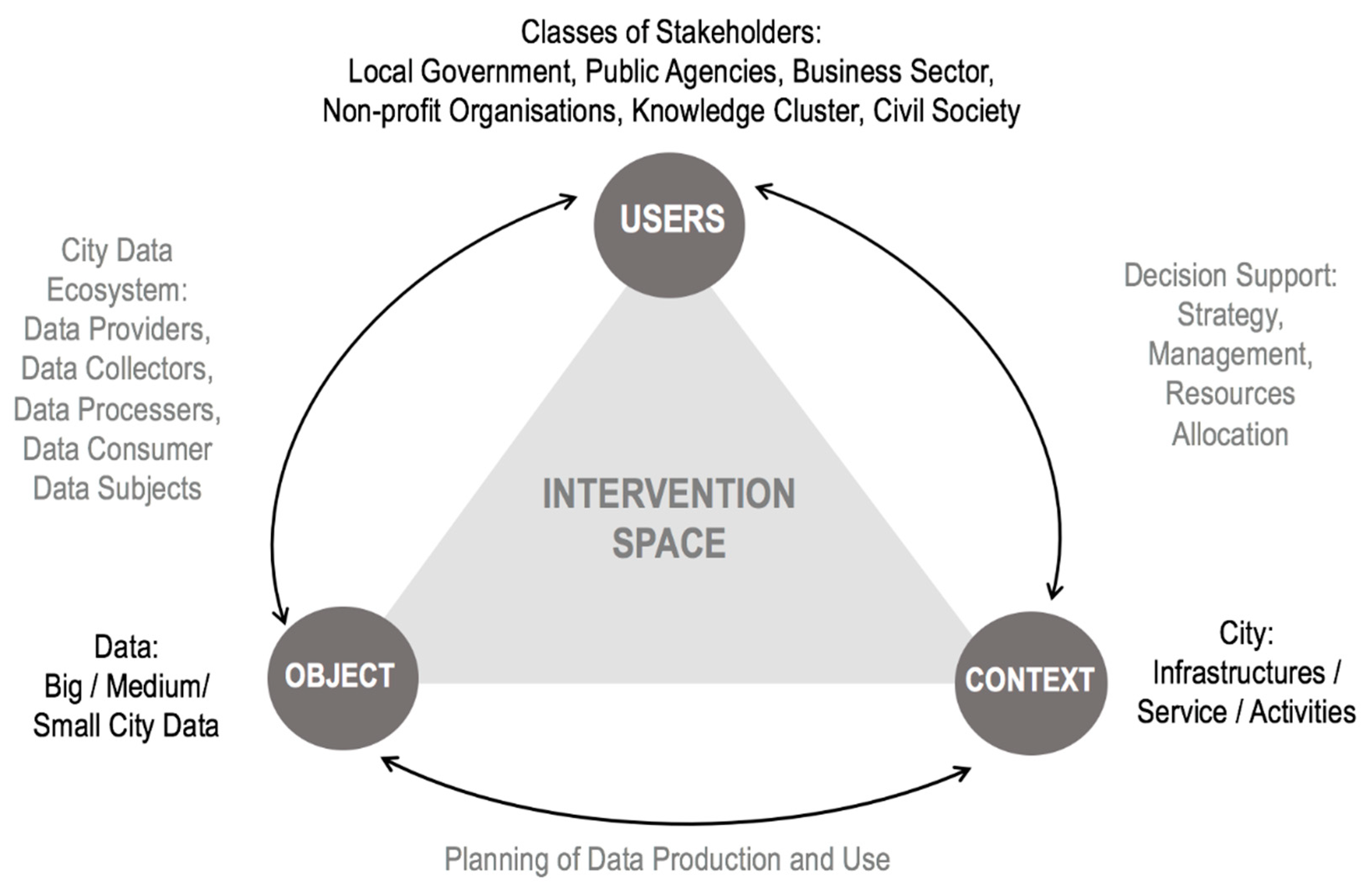

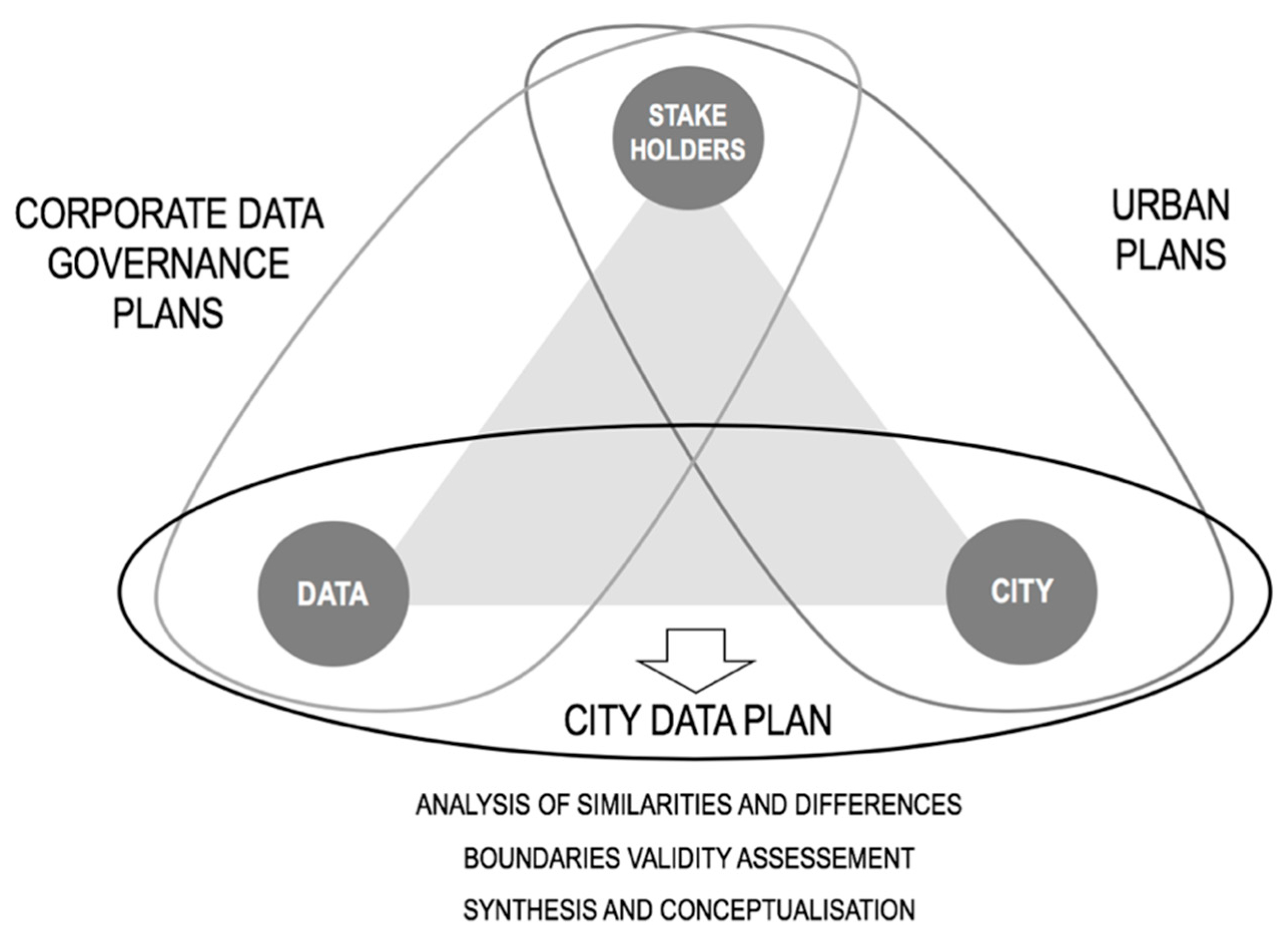

3. Approach to the Conceptualisation of the City Data Plan

- The different classes of stakeholders operating in the city as Users of the solution. They include:

- (a)

- Local governments (political and administrative authorities at the city level)

- (b)

- Public agencies (administrative and operational unit for the provision of public services at local, regional and national level)

- (c)

- Business sector (industry, commerce, private services)

- (d)

- Non-profit organisations (charities, foundations)

- (e)

- Civil society groups (citizens and informal groups)

- (f)

- Knowledge cluster (universities, research centres, R&D departments of public and private organisations, knowledge professionals).

- The city as system of infrastructures, services and activities as Context of the solution

- The production and use of small, medium and big data in the city as Object of the solution

- The connection between Users (city stakeholders) and Object (city data) had been explored in terms of relationships between city components and classes of local stakeholders related to their role in the city data ecosystem as:

- (a)

- Data collectors, gathering data in the context

- (b)

- Data processors, analysing and structuring data

- (c)

- Data providers, managing the distribution of data

- (d)

- Data consumers, using data

- (e)

- Data subjects, actively or passively providing data on their activities

- The connection between Users (city stakeholders) and Context (city activities) had been examined by taking into account different types of applications and uses of data in supporting strategic decisions, management choices or resource allocation operations.

- The connection between Object (city data) and Context (city activities) had been investigated in terms of structures and mechanisms to align the production and use of data to information needs related to infrastructures, services and local activities.

- Re-elaboration of the previous knowledge of problems and solutions having characteristics similar to the problem of the city data governance (in this case, corporate data governance plans and urban plans)

- Abstraction of their essential characteristics, such as components and logics

- Generalisation of schema and patterns of the analysed solutions for their transferability to a new problem, the governance of city data in multi-stakeholder context

4. Developing the Concept of the City Data Plan

4.1. From Corporate Data Governance Plans to the City Data Plan

- Installation and maintenance of the technological infrastructure related to sensors

- Exclusive rights of the technology provider and its sub-contractors to operate on data

- The supply of data-related services to the direct client signing the agreements

- The right to extend access to data to authorised entities

- (a)

- Increasing revenues and values of data seen as company assets

- (b)

- Containing the costs associated with the growing complexity of data management processes

- (c)

- Addressing communications issues with external stakeholders

- (d)

- Reducing risks and problems related to security, privacy, compliance with established regulations

- (1)

- Dedicated organisational bodies composed of representatives of both the company and the relevant stakeholders expected to establish collective goals, a shared decision-making framework and responsibility assignments

- (2)

- Well-defined standards and processes involving data

- (3)

- A set of technologies to support these processes, not necessarily self-included in the systems for data production and management.

- A multi-stakeholder advisory board operating at the urban level

- A cross-sectorial teams of domain experts and data experts, affiliated with and representing the different data providers in the city data ecosystems, instead of a team of data experts internal to the public administration

- A coordination team to support the communication and cooperative operations among the different technical/not technical teams of data providers and data users, instead of a centralised technical team within the public administration

- A team specialised in direct emergency response (for severe crisis) and coordination of emergency response across the technical teams associated with the plan for low-level risks, instead of one team for a centralised emergency response team.

- The definition of their organisational goals

- The position of the decision-making power (defined as “locus of control”)

- The roles and responsibilities covered by each person implementing the plan [45].

- (a)

- Responsible for the execution of activities

- (b)

- Accountable for the activity and therefore making and authorising decisions

- (c)

- Consulted to provide inputs and support before that a decision is taken

- (d)

- Informed of decisions and their outputs [50]

- (1)

- Within the single organisation participating in the city data ecosystem in the capacity of data producer or data user

- (2)

- Among the subsets of organisations implementing interdependent data-driven or data-dependent activities

- (3)

- Across different subsets of organisations covering the same domains or running similar operations to establish minimum standards and common operational principles

4.2. From Urban Plans to the City Data Plan

- Compensatory mechanisms should incentivise the production and sharing of data having a public interest and community applications, but not constituting the core business of the organisations able to produce them. The acknowledgement of the public interest and distributed benefits linked to the production of specific data can be related to a redistribution of costs. In this sense, the data featurization proposed by Finch and Tene [38] could become a standard sustainable practice at an organisational level. This practice should be extended not only to major data producers, but also to organisations actively producing data-related services in local communities or companies having the opportunity to collect data of public interest even if that operation is not in their core business.

- Monetary and non-monetary disincentives should be applied to penalise the overproduction and distribution of data generating unsustainable overloads for local infrastructures and organisational resources. Other disincentives can be applied to the production of data having evident discriminatory or malevolent applications previously identified.

- Data rights transfers mechanisms should support the exchange and reciprocal access to data between subsets of organisations that operate in the same area or benefiting from synergic efforts (e.g., by avoiding the replication of data collection or data analysis processes). These rights can be granted temporarily, in line with the needs of the involved organisations, but in compliance with the rules established in the CDP. The principles regulating data rights transfer mechanisms are established by the multi-stakeholder advisory board and operatively managed by the cross-sectorial domain and data experts’ teams.

5. The City Data Plan

- (a)

- Preparation and management of the CDP

- (b)

- Contents of the CDP

- The mapping of local organisations indicates their roles and levels of engagement in the city data ecosystem.

- The mapping of available data indicates the existing data sources covering each area of the city at various scales (e.g., metropolitan area, district, neighbourhood, building block) and on different domains (e.g., mobility, energy, community, urban development, business). These data sources include big, medium, and small data available under the conditions established by each organisation (e.g., free access, fees payment, data exchange) within the rules of the CDP. Updates on the available data sources can be independently shared on the map-based system by each organisation.

- The mapping of information needs and targets by area and domain consist of the list of data (small, medium, big) to be produced in the short, medium and long term, as part of the general CDP or sectorial sub-plans. The survey of the information needs of local organisations can be initiated in the preparatory phase of the City Data Plan (as part of the “primary infrastructuring activities”) and then dynamically updated over time. The targets actively supported by the institutions contributing to the CDP are established by the advisory board in relation to the development goals of the city, and then detailed by the operational units. The description of information needs and targets is complemented by the list of incentives, disincentives, and data transfer mechanisms oriented to facilitate and support their fulfilment.

- The mapping of on-going data generation processes and applications of city data currently in use includes the list of actors participating in the process (by domain, area and scale) and the “rules of engagement” for third parties interested in entering in the process, reusing the produced resources, extending the data sources to other domains, areas, or scale of intervention.

- The mapping of archived data sources by owner, area and domain works as the index of inactive data resources, not in use, but potentially required for future uses. They can include, for instance, reports, projects, surveys, datasets not updated anymore.

- The list of principles and operational recommendations to separate IT governance from data governance in the agreements between data providers and data users, as well as between owners of IT resources and data services providers

- The criteria to benefit of the public or private incentives for the production of data meeting local information needs and city targets

- The criteria activating the enforcement of disincentive mechanisms and the list of limitations associated with the misuse of city data concerning the access to the CDP resources

- The conditions regulating data rights transfer of data of public interests, and the recommendations for equitable data exchange among different stakeholders in the city data ecosystem covering the roles of data subjects, data collectors, data processors, data users on one side, and the role of data providers on the other side

- The standardised communication protocols at an inter-organisational level among local organisations cooperating in the data generation and use in the same area or domain of activity

- The schema of competences and responsibilities of the institutions implementing the CDP, specifying the functioning of centralised decision-making processes at the city level, and the coordination mechanisms for decentralised operations at the level of single organisations

- The guidelines for conflicts resolution in data-related operations

- The code of conduct for the local organisations involved in the CDP institutions

6. Examples of Urban Applications of a City Data Plan

6.1. Scenario 1. Supporting Alternative Mobility Choices

- Context. The combination of intense regional and internal mobility flows determine that traffic congestion is one of the most urgent problems that Milton Keynes is facing. Road congestion due to daily commuting has a strong negative impact on the environment and the perceived well-being of citizens.

- Smart City vision (Smart Mobility). Milton Keynes as city supporting slow and alternative mobility choices to actively reduce traffic levels and improve environmental sustainability at the urban level.

- Existing IT infrastructure and data sources: Traffic sensors monitoring about 300 roundabouts in the city and over 2000 parking sensors in the city centre.

- Physical constraints. Milton Keynes has two distinct road networks. The high-way system is reserved for cars and penetrates in residential compound through low-speed local streets. The bicycle and pedestrian network constituted by the so-called “red ways” is extended throughout the entire city, but scarcely used by residents and internal commuters. The population density is very low, and the urban area is over 90 sq. km.

6.2. Scenario 2. Monitoring the Impact of Social Services Provision on Local Communities

- Context. Austerity measures and budgets cuts impose an attentive management of human resources in social and health service provision. On the other side, there is no decrease in the requests of assistance from areas characterised by high rates of socio-demographic vulnerability (due to poverty, unemployment, health issues).

- Smart City vision (Smart communities). Milton Keynes as a city where social and health services are planned and managed by monitoring and assessing the impact of area-based services.

- Existing data sources:

- -

- Local Council. Data on the provision of social services over the years.

- -

- National Health Service (NHS) facilities. Data on health services.

- -

- Office for National statistics. Census data 2011, segmented by area.

- -

- Public and private health professional associations (GP, pharmacists, nurses, homecare assistance). Data on the provided services.

- -

- Local charities. Data on assisted people and beneficiaries of their activities.

- Organisational constraints. While communication protocols are established and partially formalised between local governments and regional and national public agencies as concerning data exchange, there are no standard measures in place to cooperate with non-profit and private organisations.

7. Discussion

- As regards Users: is the CDP an instrument able to address the needs and requirements of local stakeholders participating in the city data ecosystem in different roles? Does the CDP take into account their different organisational constraints (e.g., mission, core activities, human resources)? Can the CDP be integrated into existing processes?

- As regards city data as Object of the plan: is the CDP a policy instrument able to prevent or limit the manipulation of data by technology providers and their clients? Are the measures included in the CDP potentially effective in contrasting malevolent or discriminatory uses of data at the local level?

- As regards the Context of use of data by local stakeholders: is the CDP not in contrast with other laws and regulations? Can the CDP provide support to different types of decisions and actions in the city driven by data?

7.1. Users

7.2. Object

7.3. Context

7.4. Open Challenges

8. Conclusions

- Is a policy instrument that can have a regulatory, statutory or consultative value, in compliance with the conventions of a specific normative context

- Has the form of an inter-organisational set of protocols defining goals, responsibilities, and operations on city data

- Provides a common decision framework for public and privates organisations to support city data production and use, based on local information needs/resources

- Establishes communication procedures to coordinate the city stakeholders involved in the city data ecosystem in different roles

- Includes a set of mechanisms regulating the plan implementation through incentives, disincentives, and rights transfer agreements

- Can be instantiated in a synthetic visual model mapping information needs, available or required data resources, on-going data collection initiatives, and data-in-use applications

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abella, A.; Ortiz-De-Urbina-Criado, M.; De-Pablos-Heredero, C. A model for the analysis of data-driven innovation and value generation in smart cities’ ecosystems. Cities 2017, 64, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barns, S. Smart cities and urban data platforms: Designing interfaces for smart governance. City Culture Soc. 2018, 12, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchin, R. The Data Revolution: Big Data, Open Data, Data Infrastructures and Their Consequences; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Ballesté, A.; Pérez-Martínez, P.A.; Solanas, A. The pursuit of citizens’ privacy: A privacy-aware smart city is possible. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2013, 51, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, J.; Pasquale, F.A. The spectrum of control: A social theory of the smart city. First Monday 2015, 20. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2653860 (accessed on 30 May 2019). [CrossRef]

- Van Zoonen, L. Privacy concerns in smart cities. Gov. Inf. Q. 2016, 33, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- GDPR. Available online: https://eugdpr.org/ (accessed on 20 July 2019).

- Data as Commons. Available online: https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/digital/en/digital-transformation/city-data-commons (accessed on 30 May 2019).

- TADA Manifesto. Available online: https://tada.city/en/home-en/ (accessed on 20 July 2019).

- Thorns, D.C. The Transformation of Cities: Urban Theory and Urban Life; Macmillan International Higher Education: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mazza, L. Technical Knowledge, Practical Reason and the Planner’s Responsibility. Town Plan. Rev. 1995, 66, 389–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, C. Planning craft: How planners compose plans. Plan. Theory 2009, 8, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthopoulos, L.G.; Vakali, A. Urban Planning and Smart Cities: Interrelations and Reciprocities. In The Future Internet; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 178–189. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Townsend, A. Cities of data: Examining the new urban science. Public Culture 2015, 27, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Anez, V.; Fernández-Güell, J.M.; Giffinger, R. Smart City implementation and discourses: An integrated conceptual model. The case of Vienna. Cities 2018, 78, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Buys, L.; Ioppolo, G.; Sabatini-Marques, J.; da Costa, E.M.; Yun, J.J. Understanding ‘smart cities’: Intertwining development drivers with desired outcomes in a multidimensional framework. Cities 2018, 81, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, Z.; Newman, P. Redefining the smart city: Culture, metabolism and governance. Smart Cities 2018, 1, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunder, M.; Madanipour, A.; Watson, V. (Eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Planning Theory; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Urban Complexity And Spatial Strategies: Towards A Relational Planning For Our Times; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cowley, R.; Joss, S.; Dayot, Y. The smart city and its publics: Insights from across six UK cities. Urban Res. Pract. 2018, 11, 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T. Planning for knowledge-based urban development: Global perspectives. J. Knowl. Manag. 2009, 13, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.; Richter, C. Big data and urban governance. In Geographies of Urban Governance; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 175–191. [Google Scholar]

- Barns, S. Mine your data: Open data, digital strategies and entrepreneurial governance by code. Urban Geogr. 2016, 37, 554–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchin, R. Getting Smarter about Smart Cities: Improving Data Privacy And Data Security; Data Protection Unit, Department of the Taoiseach: Dublin, Ireland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Tian, Y.; Liu, X.; Gu, D.; Hua, G. Urban big data and the development of city intelligence. Engineering 2016, 2, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barns, S.; Cosgrave, E.; Acuto, M.; Mcneill, D. Digital infrastructures and urban governance. Urban Policy Res. 2017, 35, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchin, R. Data-Driven, Networked Urbanism. 2015. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2641802 (accessed on 30 May 2019). [CrossRef]

- Kitchin, R. The real-time city? Big data and smart urbanism. GeoJournal 2014, 79, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, T.; Zook, M.; Wiig, A. The ‘actually existing smart city’. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2015, 8, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, D. Global firms and smart technologies: IBM and the reduction of cities. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2015, 40, 562–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kietzmann, J.H.; Hermkens, K.; McCarthy, I.P.; Silvestre, B.S. Social media? Get serious! Understanding the functional building blocks of social media. Bus. Horiz. 2011, 54, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, C.S.; Long, M. News sharing in social media: The effect of gratifications and prior experience. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, K.N.; Rainie, H.; Lu, W.; Dwyer, M.; Shin, I.; Purcell, K. Social Media and the ‘Spiral of Silence’; PewResearchCenter: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, R.; Sleight, P.; Webber, R. Geodemographics, GIS and Neighbourhood Targeting; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NY, USA, 2005; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Bowker, G.C. Big data, big questions| the theory/data thing. Int. J. Commun. 2014, 8, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Leszczynski, A. Speculative futures: Cities, data, and governance beyond smart urbanism. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2016, 48, 1691–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, D. Surveillance, Snowden, and big data: Capacities, consequences, critique. Big Data Soc. 2014, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, K.; Tene, O. Welcome to the metropticon: Protecting privacy in a hyperconnected town. Fordham Urb. Law J. 2013, 41, 1581. [Google Scholar]

- Decker, A. Smart Law for Smart Cities. Fordham Urb. Law J. 2016, 41, 1491. [Google Scholar]

- Rabari, C.; Storper, M. The digital skin of cities: Urban theory and research in the age of the sensored and metered city, ubiquitous computing and big data. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2014, 8, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, L.; Williamson, I.P. Spatial data infrastructures and good governance: Frameworks for land administration reform to support sustainable development. In Proceedings of the 4th Global Spatial Data Infrastructure Conference, Cape Town, South Africa, 13–15 March 2000; pp. 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, N. From a design science to a design discipline: Understanding designerly ways of knowing and thinking.”. In Design Research Now; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2007; pp. 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kolko, J. Abductive thinking and sensemaking: The drivers of design synthesis. Des. Issues 2010, 26, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G. The DGI Data Governance Framework; The Data Governance Institute: Orlando, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wende, K. A model for data governance-Organising accountabilities for data quality management. In Proceedings of the 18th Australasian Conference on Information Systems, Toowoomba, Australia, 5–7 December 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, B. A morphology of the organisation of data governance. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS), Helsinki, Finland, 9–11 June 2011; Volume 20, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, E.; Dismute, W.S.; Lwanga Yonke, C. The State of Information and Data Governance–Understanding How Organizations Govern Their Information and Data Assets; International Association for Information and Data Quality (IAIDQ); University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Information Quality Program (UALR-IQ): Baltimore, MD, USA; Little Rock, AR, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cheong, L.K.; Chang, V. The need for data governance: A case study. In Proceedings of the 18th Australasian Conference on Information Systems, Toowoomba, Australia, 5–7 December 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Khatri, V.; Brown, C.V. Designing data governance. Commun. ACM 2010, 53, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K.; Otto, B.; Österle, H. One size does not fit all—A contingency approach to data governance. J. Data Inf. Qual. (JDIQ) 2009, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, J. The Google City That Has Angered Toronto. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-47815344 (accessed on 25 July 2019).

- Wende, K.; Otto, B. A Contingency Approach to Data Governance. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Information Quality, Cambridge, MA, USA, 9–11 November 2007; pp. 163–176. Available online: https://www.alexandria.unisg.ch/213308/ (accessed on 30 May 2019).

- Frischmann, B.M.; Madison, M.J.; Strandburg, K.J. (Eds.) Governing Knowledge Commons; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Open Data Institute. The Data Spectrum Helps you Understand the Language of Data. Available online: https://theodi.org/about-the-odi/the-data-spectrum/ (accessed on 30 May 2019).

- Janin Rivolin, U. Planning systems as institutional technologies: A proposed conceptualization and the implications for comparison. Plan. Pract. Res. 2012, 27, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punter, J.; Carmona, M. The Design Dimension of Planning: Theory, Content, and Best Practice for Design Policies; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/planning-practice-guidance (accessed on 30 May 2019).

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies; Macmillan International Higher Education: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sandercock, L. Negotiating fear and desire. In Urban Forum; Springer: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; Volume 11, pp. 201–210. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, L.D. Urban Development: The Logic of Making Plans; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; Volume 166. [Google Scholar]

- Micelli, E. La Gestione Dei Piani Urbanistici: Perequazione, Accordi, Incentivi; Marsilio Editori Spa: Venezia, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chourabi, H.; Nam, T.; Walker, S.; Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Mellouli, S.; Nahon, K.; Pardo, T.A.; Scholl, H.J. Understanding smart cities: An integrative framework. In Proceedings of the 2012 45th Hawaii International Conference On System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2012; pp. 2289–2297. [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh, T. An investigation of IBM’s Smarter Cites Challenge: What do participating cities want? Cities 2017, 63, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupi, L.; Alessio, A.; De Liddo, A.; Motta, E. Actionable Open Data: Connecting City Data to Local Actions. Available online: https://arxiv.org/submit/2715230/view (accessed on 30 June 2019). [CrossRef]

- Caprotti, F.; Cowley, R.; Flynn, A.; Joss, S.; Yu, L. Smart-Eco Cities in the UK: Trends and City Profiles 2016; University of Exeter: Exeter, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Corporate Data Governance Plan | City Data Plan | |

|---|---|---|

| Goal | Design of the relationship between people, technologies and processes related to data | |

| Focus | IT assets ≠ stakeholders’ interests | Ownership of smart technologies ≠ ownership or rights on data |

| Needs | (a) increasing revenues (b) containing costs (c) reducing risks (d) improve communication | (a) increasing value of data (b) containing data mismanagement extra-costs (c) overcoming organisational barriers (d) enabling coordinated data-centred actions |

| Organisational bodies | Internal teams and coordination units with external stakeholders | (1) multi-stakeholder advisor board (2) cross-sectorial multi-team of domain experts and data experts (3) coordination team (4) emergency response team |

| Organisational goals | Formal goals: Business oriented Functional goals: Operational | Formal goals: political 3 level of Functional goals:

|

| Decision-making power | Position of power: centralised or decentralised Relationships in decision making: hierarchical or cooperative | Decentralised and cooperative at the urban level Flexibility on organisational arrangements (centralised or decentralised, hierarchical or cooperative) |

| Responsibility assignment | Roles of individuals:

| Roles appointed to organisations Internally distributed to individuals |

| Themes of decision | Uses of data Quality of data Metadata Access requirements of data Data lifecycle | Plurality of uses of data Relevance of data Appropriateness of data Legibility of data Licensing Transformability and reuse |

| Focus of decision protocols | Data quality Privacy protection Security Normative compliance Interoperability Integrability | In addition: Rules of engagement at urban and inter-organisational level Conflict-resolution procedures |

| Technologies | Technologies monitoring the data management processes Technologies supporting spatial and temporal coordination of the involved stakeholders | |

| Urban Plans | City Data Plan | |

|---|---|---|

| Goal | Regulating the access and exploitation of urban resources taking into account public and private interests in the transformation of the built environment | Regulating the access and exploitation of city data as a new layer of urban resources linked to the generation of value in the city |

| Scope | Outlining a vision for the development of the city by setting a set of desired targets to reach in a defined temporal frame | Realigning smart city visions and the output/outcome of data produced by smart city technologies |

| Nature | Municipal law or local policy | Policy instrument |

| Key resource | Land (organisations as means for the valorisation of local resources) | Organisations (data as means for enhancing the full potential of local services and social capital) |

| Risk assessment | Extra-load of existing infrastructures and built areas | Extra-workload of organisation involved in the city data ecosystem |

| Classification schema | Land use classification

| Classification of engagement /effort by type of data produced:

|

| Decisions framework | Multi-level temporally distributed | |

| Competence | Public administration:

|

|

| Implementation mechanisms |

|

|

| Preliminary operations to implement the Plan |

|

|

| Components | Descriptive documents and visual models (analogical or digital) | Integrated representation of policies and visual model of the real-time status of city data availability, planned operations, uncovered areas (supported by digital technologies) |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lupi, L. City Data Plan: The Conceptualisation of a Policy Instrument for Data Governance in Smart Cities. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3030091

Lupi L. City Data Plan: The Conceptualisation of a Policy Instrument for Data Governance in Smart Cities. Urban Science. 2019; 3(3):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3030091

Chicago/Turabian StyleLupi, Lucia. 2019. "City Data Plan: The Conceptualisation of a Policy Instrument for Data Governance in Smart Cities" Urban Science 3, no. 3: 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3030091

APA StyleLupi, L. (2019). City Data Plan: The Conceptualisation of a Policy Instrument for Data Governance in Smart Cities. Urban Science, 3(3), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3030091