Abstract

The most recent English attempts at decentralisation take the shape of the city region devolution policy agenda. Decentralisation claims to empower localities and address regional growth imbalances, while creating a variety of new temporary and selective fiscal and geographic arrangements in policy-making that have the potential to create the opposite effect. This paper focuses on the relationship between decentralisation and territorial inequalities through the analysis of strategic discourse of six ‘devolved authorities’. A quantitative, qualitative, and comparative approach to this question complements the traditional insights obtained from in-depth case study analysis using actors’ interviews. It focuses on city regions’ official discourse of self-conceptualisation and marketization, and thereby highlights the wider policy and regional theory context of their production to frame the structural factors impacting the rewriting of city regional space. By doing so, we find a number of issues with the current decentralisation approach in competing priorities between localities, an over-reliance on agglomeration economies and urban competition, potential mismatches in scales of policy decision-making and delivery, and challenges regarding inequalities in a post-Brexit England.

1. Introduction

The relationships between centralised politics and area-based policy, regional identities, and discourses of inequalities and growth have shaped England and its regional development trajectory for decades. Often referred to as the ‘north–south divide’ in wealth and opportunities or ‘the regional problem’ [,,], disproportionately affecting the ‘left-behind places’ often mentioned in post-Brexit discourse [], patterns of economic growth, decline, and inequalities have taken a distinctly spatial form commonly related to centralized governance and patterns of industrial structure and deindustrialization [], eliciting calls for a ‘spatial rebalancing’ [] and ‘placed-based policy’ [,].

In an attempt to empower localities and foster localised growth, the current U.K. Government is employing the term ‘devolution’ to refer to a process by which resources, control, and funding are gradually decentralized to local units of government []. Mostly developed in reference to the institutional and fiscal decentralisation of power to the nations, that is, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, since the 1970s, the term ‘devolution’ is now applied to lower levels of local government, namely select city regions, although critiques more closely describe it as contractual light-touch decentralisation []. This suggests that what is posited as devolution is a rhetoric related to broader, often historic, issues around political power, identities, and ideas about place and economic development [,,,,], and the processes that form the relationship between Central and Local Government in England.

The increased interest and claims for decentralisation to city regions as demonstrated by the U.K. Government can thus be summarised by two ideas derived from Coombes []. On the one hand, there is a focus on institutions and scale, the ‘basic subsidiarity logic’, which considers a lower political scale as most appropriate to manage socio-economic systems. On the other hand, there is the economic argument, as “the turn towards city-regions stemmed from recent academic emphases on city agglomeration driving economic growth” (p. 2430). Documents such as the Heseltine Review, which formed the basis of local growth and devolution funding agendas, make it very clear that the Government’s focus is on creating economic growth through city regional enterprise-led decentralisation [], rather than public service or social policy concerns (which are, in this context, considered a cost rather than an investment) and on a localism agenda suggested to be a better scale of policy-making []. In this paper, we quantitatively and qualitatively analyse a set of strategic economic plans as representative of city-region political and regional identity, as well as the nature of the relationship between Central and Local Government. We consider the two above-mentioned ideas of decentralisation towards city-regions, and wider discourses on growth and territorial inequality to better understand the underlying assumptions underpinning sub-national and city regional economic and social policy development.

We explore these questions with respect to the ‘devolution deals’ agreed between 2014 and 2016, following England’s regional reorganisation into 38 local enterprise partnerships (LEPs), and alongside growth and city deal funding. The official discourses underlying these deals (including their proposed implementation) are represented by the strategic economic plans (SEPs) that LEPs were asked to design in order to receive funding, as well as the practices of ‘deal-making’ and ‘bidding’ themselves. We use the SEPs as representative documents of sub-national decentralisation policy in England to conduct a content analysis of the discourse of six combined authorities, of the formalised process of production of ‘deals’ and of the precarious relationship between strategic claims and actual institutional reform and funding. We ask the following:

- Whether they reveal divergent outcomes and conflicting policies pan-regionally;

- What types of assumptions about social inequality and economic growth underlies both the process of their creation and their content;

- What types of founding narratives, institutions, and resources exist in the strategic documents in relation to the reality of spatial organisation.

Our hypothesis is that, despite the possibility provided by English city regional decentralisation to tailor policy instruments to local needs, the underlying reliance on agglomeration economies and other endogenous growth theories for development by the LEPs as well as the exclusion of other geographies by Central Government might result in increased inequality between cities, as well as between them and non-metropolitan areas [,], notwithstanding their unequal status regarding budget cuts and austerity []. The aim of the paper is thus to provide a comparative overview of six city regions’ self-perception of strengths and policy levers to illustrate the direction of economic and social policy in England, and through this, to scrutinize underlying assumptions about economic growth, regional inequalities, and local government.

1.1. History of Sub-National Development and Area-Based Initiatives in England

The most recent Conservative Government’s attempts to decentralise policy responsibilities and finances through ‘devolution deals’ for select English city regions were created through varying levels of deal-making and bilateral agreements. They claim to have a particular focus on empowerment through localized decision-making and city-regions as a vehicle for economic growth []. The most visible results of this policy are the creation of new institutional layers (LEPs, Combined Authorities, Metro Mayors) and new fiscal geographies (Devolution Deals, City Deals, Local Growth Funding), sometimes adding rather than replacing previous initiatives [,], or overlapping in their funding and responsibilities. Considering the non-constitutional and contractual nature of the ‘devolution deals’ [], we review them here against a history of temporary, politically motivated, and area-based initiatives.

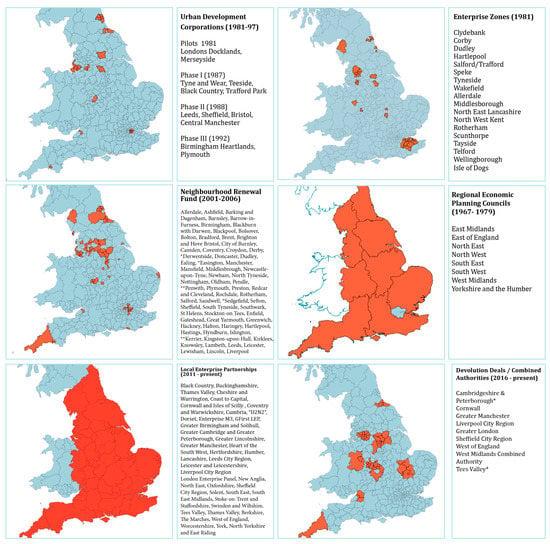

As illustrated in Figure 1, historically, the scale, spatial coverage, and economic and social policy position of English decentralisation to sub-national levels of geography have varied greatly, stemming from different understandings of growth and inequalities. Urban and regional policy has gone through different waves of reorganisation of political geography and scales of intervention. It started with the Urban Aid and the expanded Urban Programme in the 1960s, a small-scale policy with an inner city focus on poverty and deprivation. Then came a more distributed deregulation and enterprise focused area-based policies under the Conservative Governments of the 1980s and 1990s. Under New Labour, the ‘urban renaissance’ attempted at unifying social and economic policy interventions spatially alongside regional governance structures through regional development agencies, as well as their area-based policies focused on city place marketing and urban competition, which set the scene for the city region agenda []. Recently, the focus has been on a more localised, enterprise-led select ‘city region devolution’ agenda [], with an effort to foster post-crisis economic growth [], particularly in ‘left-behind’ places, set against attempts to reduce regional governance spending []. Figure 1, in this respect, illustrates the discontinuity in policy interventions, as well as the variation in spatial scales and the lack of exhaustive coverage achieved by growth-driven ‘devolution deals’, by mapping the historic variations for select area-based initiatives ranging from urban areas to enterprise partnerships to regional councils, oscillating between a social and economic policy focus. M. Coombes [] notes on this lack of coverage that, “a set of regions only partially covering the country may be useful for policies tackling issues that are limited to some areas (for example, metropolitan-scale transport planning), but no area can be simply ‘left off the map’ when defining boundaries for general territorial governance or delivery of universal policies.” (p. 2428). On the basis of this understanding, the choice of some areas over others is setting the ground rules for an acceptance of geographic inequalities.

Figure 1.

Select maps of post-war area-based initiatives in England.

What all these historic area-based initiatives have in common is that they represent temporary fiscal aid without long-term institutional or constitutional re-design. While ultimately very flexible and adaptable, there is a risk of intermittent loss of human capital and institutional knowledge with each political erasure of previous initiatives [], a short-term evaluation window in policy areas that have longer-term impacts, and a potential loss of trust in the system and its ability to produce change.

1.2. Growth, City-Regions, and Inequalities

The role of sub-national levels of government in the management of local socio-economic systems has been considered in contrasting ways in the main approaches of regional science and economic geography []. According to R. Capello [], earlier conceptions of space were stylized, limiting its function to that of an abstract container of socio-economic activity. Borts and Stein’s [] models for predicting convergence or divergence based on varying regional endowments in capital and labour illustrate this trend, as regions are represented as independent and a-spatial containers of factors of production. In this school of understanding place and economic growth, “the national growth rate is exogenously determined, and that the problem for regional development theory is explaining how the national growth rate is distributed among regions. According to this logic of competitive development, the growth of one region can only be to the detriment of the growth of another region, in a zero-sum game” [§16,27]. When regions do not necessarily converge towards similar levels of development or fast enough (unlike some early predictions by neo-classical growth frameworks), or when the factors of production are not as mobile as hypothesized to equalise costs and revenues between the different regions, policies under this theoretical approach are thus considered fairer when applied at the higher, central level of government to counter-balance the inequalities related to the spatial distribution of resources.

A later conception of space relevant to our considerations of spatial scale, economic growth, and territorial inequality is termed ‘diversified-relational’. This means that regions and cities are viewed as diverse territories, in which the relations and interactions between agents across space create the conditions for endogenous development and growth, and can thus be considered as particular, yet in relation to each other. The aggregations of local growth dynamics make up the higher level aggregate national growth in that framework (rather than a disaggregation from the top down). Endogenous growth theories, as well as the idea of agglomeration economies under the new economic geography, opened the way to this conception in economics to some extent, although they still considered space as an abstract container rather than as a relational territory. Endogenous growth oriented policy combined with a knowledge intensive economy is prone, in this context, to produce spatial differences in performance and divergent trajectories []. Considering prominent growth theories and the role of place, Central Governments are presented with two main strategies: either enter an increasing process of fostering ‘winning regions’ and redistributing some of the gains to less developed regions at the national level; or try to incentivise ‘lagging’ regions and cities to manage their own endogenous growth process (under the premise that they might better understand the network of relations, growth drivers, and policy levers locally), by decentralising policy levers and fiscal resources to them. This last option resembles the current shift to city region decentralisation, but it ignores the diversified-relational interdependency between the city regions themselves in the process of production, knowledge circulation, migration, and trade, when, in fact, urban geography has shown the importance of interactions between cities in their socio-economic convergence trajectories [].

The current focus on urban agglomerations as a method for increasing aggregate growth, along with research promoting city-regions as the “adequate” scale for governing economic growth in a globalised world [,,], has found favour not only in World Bank discourse, but is also visible in the English policy context. It is related to a wider focus on cities and their agency in policymaking, presenting cities as superseding nations in international competition and corporation []. Specifically, in relation to the English regions, however, agglomerations-driven policy can be understood as predominantly modelled on the neoliberal London ‘success’ model [,]. In this manner, the discussion around city-regional growth and how to focus financial and governance means towards it has eclipsed other spaces outside the city region boundaries and the question of territorial inequality and social policy []. It has also eclipsed the role of policy levers to address these social and territorial gaps. Research suggests that this exclusive approach can mean that “city-regions reinforce, and have the potential to increase, rather than resolve, uneven development and socio-spatial inequalities.” [] p. 247. On the contrary, European Union (EU) policy in particular has traditionally pursued a ‘cohesion’ policy of redistribution between regions through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and the European Social Fund (ESF), but has increasingly changed to a policy of fostering growth in all regions, including lagging regions [], under the Single European Act (1986) and the Lisbon Treaty (1992). This is relevant to the future of areas outside the selected devolved city regions, particularly since the referendum vote to leave the European Union, as research has illustrated that ESF funding fills a gap in U.K. regional funding, policy, and governance structures, and its loss will pose a great challenge to more disadvantaged areas [,,].

1.3. Decentralisation: Theory Versus Practice

Differing understandings of ‘devolution’ exist in the current English and U.K. policy discourse, interchangeably used for constitutional devolution to Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, as well as the English regions. The United Kingdom is often referred to as one of the most centralised states in the developed world, particularly in its relationship with Local Government [,], and while decentralisation can be understood from a constitutional and democratic empowerment point of view (i.e., regional and metropolitan movements such as Catalunya or the Basque Country; or pan-national city organisations such as EuroCities, or C40 []), it can often relate to broader questions of history, political process and power, national and regional identities, fiscal and taxation revenue issues, and uneven economic development [,,,,].

According to Mitchell [], devolution includes the following three components: “the transfer to a subordinate elected body, on a geographical basis, of functions at present exercised by ministers and Parliament”. In the U.K. context in particular, the term ‘devolution’ has historically been used for Westminster’s relationship to its regions—Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales—and centered on constitutional devolution and the establishment of separate regional parliaments [,,]. In comparison, the current U.K. Government discourse around English ‘devolution’ to city regions defines it as the process by which the State hands over some of the competencies (relating to transport, skills, planning, business support, and housing, mostly) and resources (the retention of the surplus generated by the business rate growth, for example) to lower scales of government in an attempt to better fit the policies to the needs and workings of local areas []. This step is more akin to a stage in a process of decentralisation rather than devolution per se. Although Calzada [] notes that, in many cases, political and democratic powers are the core elements of devolution processes and can provide great gains for local governance, very little actual civil and democratic involvement has featured in the ‘devolution deals’ []. In contrast, the geo-economic argument seems to dominate current political discourse around urban devolution globally and nationally, focused on the future of cities as growing demographically, enticing further growth and innovation [] (within policy discourse, see World Economic Forum, World Bank, 100 Resilient Cities, Centre for Cities, Core Cities, Future Cities Catapult). In summary, the political argument consists of matching scales of democratic representation with the scales of decisions over local and regional communities [], whereas the economic rationale behind devolution derives from the use of local knowledge and capabilities to realise localities’ growth potential. It is important to note that, despite the use of the term ‘devolution’ with regards to city regions, the realities of partial policy and fiscal allowances given by Central Government and administered by a small number of core major city region areas with varying institutional set-ups are not ‘devolution’ in the institutional and constitutional sense as described by Bogdanor above [], but more akin contractual agreements [].

1.4. What is at Stake?

The potential downsides of the current English decentralisation paired with the city-region agenda and its implementation are manifold. The first one is that although the diversity of layers seems like an opportunity to match policies with their appropriate scale of governance and funding, it also bears the risk of creating more confusion and losing sight of fragmented sets of separate policies [] across varying geographies. It matters in England with regards to the differing institutional priorities and remits between policy layers. These include corporate-led, non-elected LEPs and new resource-sparse institutions such as combined authorities. The creation of LEPs follows the Heseltine Review [], where the Government set out their objectives to put LEPs (as geographies perceived to be more representative of functional economic areas, although most of them are not credible self-contained functional areas according to Pike et al., []) at the centre of the local strategy, enabling them to obtain control over setting funding and responsibilities linked to their local growth priorities for the long-term and across the wider LEP areas. This level of input raises questions about the differential weighting of corporate LEP concerns and Local Government social policy concerns, and the impact of these competing emphases on decision-making in the various areas and their overlaps. It also deepens the challenges of policy evaluation and intra- and pan-regional coordination. The second risk associated with decentralisation is that it can increase inequality among cities and regions [,,,,], as well as the general imbalance between ‘devolved’ authorities and territories without such arrangements [,,,]. A divergence of the quality of service and accountability has, for example, been observed after the decentralisation of health services to U.K. nations, giving rise to the expression ‘divergence machine’ to qualify the devolution process []. A third risk associated with decentralisation in general, but more specifically with decentralisation in the context of austerity is that ‘city-deals’ made between the state and local business elites might circumvent democratic representation of citizens and depoliticise governance of devolved city-regions [,], and take place in authorities with varying access to resources, funding, and skills []. In this paper, we suggest that the lack of coordination of city-regional policies in the name of local competitiveness [,] might also provoke conflicting outcomes, especially if and when zero-sum game policies (such as “attracting talent”, “attracting capital”) are implemented simultaneously in different locales. This zero-sum game is different from the resource allocation of early regional theories because it results from the idea of the circulation of labour and capital rather than their creation. The philosophy of competition and agglomeration economies behind the English decentralisation policies exists in the U.K. context of Whitehall, Westminster, and London/South East dominance, where the economic dominance and contribution of the centre to national output has justified the reluctance for sub-regional devolution, further exacerbated by constitutional particularities such as the lack of a written constitution and spatially disparate, short-term policy interventions that further cement dependency from Central Government []. While there have been some attempts at some pan-regional coordination through mostly political constructs such as the Northern Powerhouse, or the Midlands Engine, these have proven to be subject to central political favour and again have little institutional, or constitutional, strength.

2. Methodology

For our analysis, we focus on the following six combined authorities: West Midlands, West Yorkshire/Leeds City Region, Tees Valley, Liverpool City Region, Greater Manchester, and Sheffield City Region, with the intention of a particular focus on city regions in the Midlands and the North, to explore the ‘northern’, historically considered ‘lagging’ regions of the so-called ‘north–south divide’. We thus exclude devolution deals in Cornwall, West of England, Cambridgeshire & Peterborough, and London, and withdrawn bids for the North East, Lincolnshire, and North of Tyne. We use a set of comparable combined authorities’/city regions’ original strategic economic plans available at the time of analysis (in 2017) to compare the way they identify their assets and challenges, as well as the set of policies proposed. The diversity of discourse-making in the six case studies is reflected in some sense by the levels of policy, financial, and political decentralization, which were under discussion in 2016 (Table 1). If some cities were considering a complete package of responsibilities, funds, and a metro mayor (Manchester and Sheffield, with four areas of full responsibilities or West Midlands with two), others were lagging behind in terms of funding (Leeds and Tees Valley) and decentralised responsibilities (Leeds, Liverpool, Teas Valley). The fact that the Tees Valley and West Yorkshire/Leeds deals have since collapsed as a result of institutional and political area-based disagreements is thus not surprising.

Table 1.

Level of policy, financial, and political decentralisation in six English city regions.

While they have since been complemented or superseded by other sets of growth-centered and/or city regional policies (for instance, the Industrial Strategy Green Paper and White Paper 2017, Local Industrial Strategies 2018/19, an updated GMCA (Greater Manchester Combined Authority) Growth Plan, a second Tees Valley SEP in 2016), ‘devolution’ deals remain the major decentralisation instrument and we limit our investigation at the original iteration of this phenomenon and the circumstances of its founding.

We perform the analysis in two ways. First, a quantitative analysis of the six documents utilises text mining tools to draw out a summary of the themes, lexicon, and word-associations in the strategic documents of selected authorities, using the tm package of the R programming software (to remove common fill words, punctuation, and so on). This part of the analysis provides a data-driven, numerical view on the language chosen to write the SEP documents, ranking lexemes by scaled frequency of occurrence and measuring word co-occurrences. Second, a qualitative analysis explores the content of the policy documents and compares their understanding of main regional development drivers such as sectoral specialisation, skills, and transport policy, in order to highlight the similarities and differences between strategies taken by cities, and how they relate to expectations from regional theory. While the process of decentralisation is complex on an institutional and a fiscal level, analysing the SEPs as pieces of political communication can reveal the institutional practices and ideologies underpinning the syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic aspects of the text and the mode of their production []. As texts can also be read as embedded into “practices [that] systematically form the objects of which they speak” [], p. 49, we frame SEPs in the context of their production and surrounding practices in three layers, namely, the core text, the discursive practices, and the socio-cultural practices in which the production of the texts is embedded [,]. The SEP texts are considered here as self-conceptualisation that forms part of the foundation myth of ‘devolution’ as enabling economically competitive place-making of locations, their economic identity and perceived strengths and challenges, and available policy levers. In addition, the documents are also exercises of place marketing, idealised policy and funding wish lists, which can, in some cases, not accurately reflect the actions that will actually be applied to these territories [], particularly in the comparative absence of real institutional or constitutional devolution, such as seen in differing scales with Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. The analysis takes inspiration from Robson, Peck, and Holden’s [] analysis of the regional development agencies’ regional strategies for area-based regeneration.

In overview, the six documents present the following similarities and differences in their content and modes of production and ability and resources to conduct their own analysis and evaluation:

- The West Midlands Combined Authority (CA)’s strategic economic plan, ‘Making our Mark’ [], p. 58, created by the Black Country Economic Intelligence Unit of the Black Country Consortium (LEP), is structured by mapping out policies in a defined set of key smart specialisation sectors similar to other city regions and combined authorities, and then focusing on policy areas of HS2, skills and employment, housing, and the wider West Midlands geography. It is supplemented with more detailed appendices including the dynamic economic impact model, created by David Simmons consultancy, with input from City REDI at University Birmingham Business School, and Oxford Economics model for macro-level analysis and vision setting, making the West Midlands supporting documentation the most comprehensive, yet externally sourced.

- The original Tees Valley’s SEP [] from 2014 is the most comprehensive document, with 130 pages, SWOT analyses, a number of detailed maps identifying programmes, capital assets, and sector clusters by location. It includes in-depth analyses of existing capital assets, supply chains and intra-sectoral and intra-firm linkages, detailed funding allocation plans, projected returns on investment in the form of jobs, and Growth Value Added (GVA) for its different core objectives. The analysis for the SEP was created with the help of EkosGen, an economic and social research consultancy with offices in Manchester, Sheffield, and Glasgow (also employed by Sheffield City Region).

- West Yorkshire/Leeds City Region’s SEP [], p. 97, is more aspirational and place-marketing focused in its tone, but has a similar structure to Sheffield City Region’s SEP, emphasizing productivity and the roles that business growth (particularly in Research & Development (R&D), exports, and higher skilled jobs), skills development, clean energy, and infrastructure play in this. It is underpinned by a separate economic impact assessment, with the city region drawing upon a regional economic model provided by Experian Business Consultancy, and the Regional Economic Intelligence Unit. For its ‘approach to intelligence and analysis’, the SEP references the What Works Centre for Local Economic Growth, the Institute for Transport Studies at the University of Leeds, and Working Groups coordinated by BIS. Compared with other SEPs, however, the city region distinctly outlines the idea of ‘good growth’ that runs through its strategy and links to an existing city-wide initiative titled ‘Strong Economy, Compassionate City’.

- The Liverpool City Region’s SEP [], p. 64, ‘Building our Future’, is organised into a section setting out the ‘strategic direction’, and followed by three separate mission-based topical strands, namely those of ‘productivity’, ‘people’, and ‘place’. The LEP who compiled the SEP operates ‘North West Research & Strategy’, a full-service research agency to provide intelligence and analysis for the CA. The strategic approach is framed in the context of a business-led strategy for growth. For example, the SEP outlines a number of businesses and R&D hubs and assets across the region to support growth, in conjunction with the local growth hub, intended to provide coherent and comprehensive brokerage service, similar to the discontinued regional business link services through the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). The ‘Productivity’ chapter focuses on sectoral ‘assets’, ‘opportunities’, and ‘trends’, analysing these in depth for identified core sectors, which correspond to the Northern Powerhouse capabilities, in addition to the visitor economy and maritime logistics.

- Sheffield City Region’s [], p. 56, strategic economic plan is clearly structured as a bid document, titled ‘A focused 10 Year Plan for Private Sector Growth’. It uses the Regional Economic Intelligence Unit, Ekosgen consultancy, and SNC-Lavalin for their research reports. The document outlines current strengths and weaknesses in economic development, with a particular focus on business development, high-skilled job creation, export potential, and infrastructure to increase competitiveness and productivity in the region. The SEP associates economic development with spatial development as it maps out ‘seven long-term spatial areas of growth and change where a significant proportion of growth is expected to occur’.

- Greater Manchester CA’s Growth Plan ‘Stronger Together’ [], p. 77, is set out as an aspirational bid document. Greater Manchester CA’s (GMCA’s) research and analysis is carried out by New Economy Manchester (GMCA’s research consultancy section). The city is positioned as a place for opportunity to ‘exploit its assets and meet the changing demands of the global economy’. As the document did not reveal much about sectoral strategies and was created at an earlier date than other SEPs, we also consulted the New Economy Manchester’s Deep Dive [] on sectors. The document sets out an analysis of various key sectors (including most of the Northern Powerhouse prime capabilities), adding that the city’s economic strength is in its diversity.

3. Comparative Review of Six Strategic Economic Plans

3.1. Lexical Frequency Analysis

A baseline glance at the policy documents reveals differences in the length and volume of terms. Liverpool City Region and West Midlands have the shortest documents. By contrast, the Tees Valley SEP has three times more terms, while Leeds’ has twice as much (Table 2).

Table 2.

Scaled frequency of the 10 most over-represented terms in each document. Only the 10 most frequent words are reported for each document, although two documents can have the same terms in their top 10. We use scaled frequency to compare the frequency of terms relative to the average and dispersion of frequencies of each document. * Terms have been reduced to their root form.

When we look at the most recurrent terms in the core texts, we find that economic terms dominate the SEP and equivalent documents. “Growth” and “business” are among the 10 most cited terms in all 6 documents, indicating the leading policy objective. The only other common term is “will”, as an indication of the obviously prospective nature of intentions displayed in the documents. More than the infrastructure and transport driver for growth and productivity (which has no dedicated terms in the top 10 of any SEP), the sectoral mix seems to be considered a crucial factor of growth. For example, we find mentions of “sector” in two-thirds of SEPs. Leeds and the West Midlands are the only two strategies to mention “skills” very often (more than 10 standard deviations more than other average terms). Surprisingly, innovation appears only once in these highly used terms (in the West Midlands document). Finally, SEPs are very different with respect to the inclusion of the role of place, or an explicit spatial strategy, that is, using terms corresponding to geographical scales of references such as “nation”, “region”, or “area”. The North East document has 4 of these spatial terms in its top 10, whereas the Tees Valley SEP has none, and Manchester and the West Midlands only one. Significantly, none of the top used terms relate to a higher scale of coordination, redistribution, or inequality.

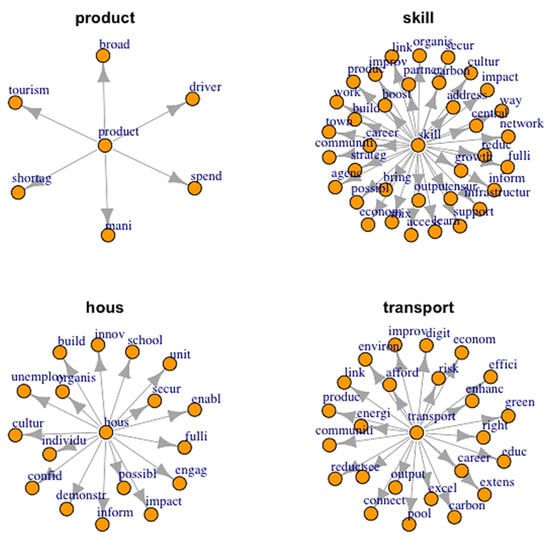

By looking at associations of words with correlations of targeted words over 0.9, we find that some words are very central to the policy documents’ lexicon. This is the case with the lexemes “skills”, “invest”, “infrastructure”, “innovation”, and “growth”, but also the sectors of “advanced manufacture” and of “low carbon”. Some words that are highly cited in general are not necessarily associated with other words in a systematic manner. This is the case for “business”, “product”, “employ”, and “job”, for example. Four terms stand out in terms of their associations with other terms throughout the documents (Figure 2):

Figure 2.

Highly correlated words in strategic economic plan (SEP) documents.

- “product*”, which covers the notions of product and productivity, is associated both with main growth drivers and a shortage.

- “hous*” is used alongside school, unemployment, and culture within the social policy spectrum of challenges.

- “transport” is associated with career and excel*, affordable, affici*, connect*, and carbon, indicating the perceived role of transport as a connector spatially, but also across policy levers.

- “skill*” is extremely central to the network of lexemes, mentioned in association with improve, boost, address, organis, strateg*, impact, and ensure—indicating that skills are identified as a key challenge for economic growth in SEP documents.

The quantitative review of SEPs thus reveals a common trait: their business and growth-oriented character. It showed a difference in focus on the factors of place, and innovation in different city-regions, and the central position of skills, sectors, and transport in the strategies.

3.2. Discourse and Discursive Practice Analysis

Within the context of the institutional and socio-cultural practices of the texts’ production, the SEPs can be considered pieces of political communication. The practice of requiring a submission of business strategic ‘bid documents’ to compete for Central Government funding provides the institutional framing of their production. The fact that Central Government refers to this policy agenda as ‘deals’ reveals the context of corporate, competitive, and specialised agreements and distribution, potentially limiting the scope and production of documents and respective policy levers.

The documents are set out as business plans, varying in their level of detail. Most contain projections for employment and GVA growth, some go into detail on sectoral strengths and spatial organisation (Tees Valley, Liverpool), while others (Manchester, Leeds) read as aspirational ‘sales pitches’. Some contain textual and quantitative details on projected policy and growth targets, measurement and evaluation tactics, as well as governance and delivery mechanisms.

Reinforcing the quantitative findings, the qualitative analysis of discursive and production practices surrounding the SEPs shows that the documents are predominantly located within business strategy, growth, and economic discourse, rather than public policy or governance discourse. This results from the process of bidding for growth-led funding to which their production is related, the dominance of growth and enterprise-led policy of Central Government, as well as the role of LEPs in leading ‘bids’ rather than local authorities. Because the former (non-democratic bodies of representation) tends to focus on the interests of business, whereas the latter have a wider portfolio of responsibilities, in this framing, social policy concerns play a secondary role, and if they are mentioned, are related to their benefit for economic growth processes and productivity.

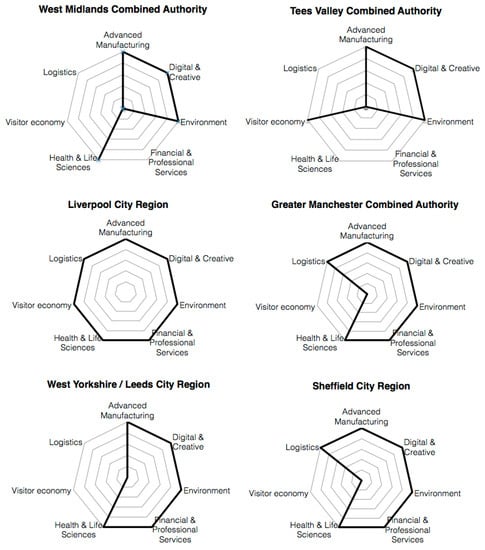

As is evident from Figure 3, the content covered by the SEPs is relatively uniform, covering a similar set of ‘key sectors’, and standard strategies to foster growth, such as transport, skills, innovation, capital projects, investment, and business support. The variation between strategies is mostly visible in the way these key components are presented and narrated, as well as supported by quantitative information, maps, and evaluation frameworks. Some differentiation can also be found in how sector or mission-led the strategies are, and the strength of their understanding of spatial factors and place in relation to development activity. The complete presentation of each strategy is available in the Supplementary Material.

Figure 3.

Sectoral policy focus areas for six selected city regions/combined authorities.

Comparing this framework to Robson, Peck, and Holden’s [] content analysis of the RDA strategic plans, the previous administration’s large-scale overhaul of regional policy in the United Kingdom, it is evident that some sectors with frequent mentions in 2000 have disappeared altogether or as a distinct category (IT and Communications, Automotive, Food, Electronics, Agriculture, Textiles), while others have appeared (Advanced Manufacturing, Digital & Creative) or gained in prominence (Medical and Life Sciences, Low Carbon). This development reflects industrial structural change to a certain extent, as well as an emphasis on high-return sectors with growth potential of the KIBS category, or an upgrading of traditional sectors to KIBS status (manufacturing to advanced manufacturing). It also suggests a failure to address the foundational economy (food supply, energy distribution, telecommunications, housing, personal, and social services), which is at the core of many smaller, non-urbanised areas across England [], as well as the role of the public sector, which accounts for a large number of jobs (27% nationally) in areas where private sector growth has been slow []. Compared with the 2000 review, most documents also miss a dedicated social policy focus (‘community regeneration’, ‘sustainable development’, or ‘social inclusion’). The documents that mention it indirectly are Leeds City Region/West Yorkshire (‘good growth’) and GMCA (‘vulnerable communities’), although social policy tends to be heavily linked to economic policy drivers, such as skills for jobs and productivity, transport to connect people to jobs for productivity, or place as an investment and talent attraction opportunity.

3.3. Capital Investment, Labour Mobility, and Urban Competition

It is evident from the content of the SEPs that, for the purpose of addressing lagging productivity, most LEPs rely on mechanisms of external investment, labour mobility (‘attracting talent’), firms, and trade, either permanently or through increased connectivity with other city regions. For example, the second pillar of Liverpool City Region’s strategy (“People”) aims to increase skills by “developing existing talent and attracting new talent” [], p. 5. The strategy set a target of 50,000 incoming residents by 2040. In Leeds, “attracting talent” is also a priority [], p. 9, for example, as students to fuel innovation and the start-up scene, in order to become “the graduate capital for tech skills” (p. 67). The West Midlands strategy seeks to attract high-income earners and skilled workers using an “accelerating housing market [with] a sustainable mix of homes for sale and rent” [], p. 6. In the Tees Valley, the target population is business leaders. A key element to their strategy is to “change the external perceptions of Tees Valley through the arts, cultural and leisure offer” [], p. 5, through the development of “town centres’ vibrancy” (p. 32). In Manchester, the way to go for attracting talent and entrepreneurs seems to be “safe, sustainable and healthy places” [], p. 23, as well as a “global brand”. The quality of place in general (housing, services, local culture, environment) seems key to attract skilled labour.

A lot of the focus in recent years, in English local economic strategies in particular, as well as the industrial strategy, has been to tackle the drivers of individual productivity. Policy makers see skills supply as the single most efficient solution in that matter [,], although some scholars [] estimate its share to lie below 20% of the productivity gap between the United Kingdom and more productive countries such as France or Germany. Public investments in skills have to consider skills and sector matching based on demographics []. Given the time scale of education, short-term strategies include the attraction of a skilled workforce from the outside and an overreliance on labour mobility and connectivity, although the relationship between transport connectivity and economic growth is complex [,]. However, because neither England nor the United Kingdom is not a bottomless reservoir of skilled workers (and it might restrict its immigration policy as a consequence of Brexit), the devolved authorities will end up competing for the mobile skilled workers in a zero-sum-game, but with unequal resources. It is likely that the most successful cities at present (Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds), with their more international employment profiles, will be better equipped to attract young professionals and engineers than less prosperous cities (Sheffield, Tees Valley), because they offer better alternative economic prospects and lifestyle opportunities. The North East, which failed to obtain a devolution deal, sums up the issue in their 2016 strategy plan: “There is some evidence from reports comparing performance of second-tier cities that Newcastle and the North East LEP area provides career escalators which can attract and retain labour, in particular for incoming migrants. However the North East economy is not as powerful as London and the South East, and other comparator cities.” [], p. 21. By contrast, rather than public investment in supply-side or labour mobility initiatives alone, a policy focus on skills demand, employer-side intervention, and multi-stakeholder capital projects (i.e., HS2 academies in the West Midlands, linking of HE, industry and local labour, and skills in Sheffield City Region) is also promoted as a strategy to address skills mismatches, lack of quality jobs, and growing in-work poverty observed in England [,].

Similarly, the attraction of successful firms and investment from the outside looks like an easy win in policy documents. For the Tees Valley combined authority, which brands itself as a “region with growth potential to be unlocked”, attracting new firms and investment is the number one priority. It is priority number three for the Sheffield City Region: “it will be vital to attract more existing businesses from outside the area to locate here, as the existing business base will not generate the scale of growth required.” [], p. 21. The means to achieve business attraction in the strategy documents are rather diverse. For the Leeds City Region, the answer is in “a better connected airport [...] to promote business growth in our key sectors and other industries, and to attract more investment.” [], p. 84. In the Tees Valley, “there is a need to further diversify the economic use of existing town centres to attract and retain the vital knowledge intensive business sector.” [], p. 4. The Liverpool City Region builds on previous experience with two enterprise zones (EZ). However, as urban economics have shown, “evidence warns us that EZs often involve spending money (or equivalently forgoing taxes) to shuffle employment around within cities” [] (pp. 189–190), rather than to create new value. Once again, the North East seems to be the most lucid about inter-city competition, even though this pessimism might have hampered their deal’s chances of success: “Whilst the volumes have been high, overall, the North East LEP area has a relatively low proportion of employment in foreign-owned companies, accounting for just 7.8% of employment in 2011, compared to 22.1% in Leeds City Region, 13.2% in Liverpool City Region and 12.6% in Greater Birmingham and Solihull.” [], p. 18.

4. Discussion

4.1. Area-Based Funding, Institutions, and Governance

Both the context of their production and the content of the core documents indicate a focus on a competitive, place-marketing, corporate-led policy agenda based on funding, over one that is anchored in broader social policy concerns, institutional reform, and long-term change. While this is not new in the relationship between U.K. Central Government and Local Government in attempting to ‘rebalance’ regional disparities, the extent, breadth, and geographic variation of fiscal and policy decentralisation to small areas without considering long-term institutional reorganisation and legacy run the risks of delivery failures and uneven development. This is particularly pertinent considering the impending post-Brexit loss of European Union cohesion funds for lagging regions regardless of their administrative geography.

Although evaluative evidence [] indicates that the regional tier is useful to address market failures, the 2010 coalition Government considered the regional tier as insufficient as a geography pertaining to functional economic areas and labour markets, and preferred the more local, enterprise zone driven level of intervention, intended to give rise to better policy coordination for growth, steering away from the perception of a ‘bureaucratic regional QUANGO’. As Pringle et al. [] remark, however, the ideal structure for intervention is one that is multi-layered, with a local coordination of labour markets; a regional level decision on sectoral policy; and a pan-regional or national action regarding strategic transport infrastructure, supply chain coordination, and innovation policy. In any case, England skips a scale of geography of coordination and accountability, the regional tier, which is represented at varying strengths in other European countries. This does not only have significance for economic policy coordination, but also raises the question of whether a divided geography of disparate small areas is a sustainable and adequately weighted governance structure to interface with Central Government on the shaping of policies and fiscal transfers [], or rather foster a ‘divide and rule’-based dependency. Although a number of non-elected pan-regional organisations were set up, most notably the Northern Powerhouse and the Midlands Engine, their development and role have varied with political change, and been strongly anchored in regional identity marketing, with the most tangible expression of the Northern Powerhouse being Transport for the North.

Quite obvious challenges and risks in this respect are the possibility of fiscal and policy decentralisation without adequate institutional arrangements, without adequate benchmarking, or without evaluation arrangements. It could also induce a competitive approach that invites localities to bid in a ‘wish list’ format without necessary institutional knowledge and arrangements for delivery and measurement and produce great variation in devolved finances and policy levers between localities, setting them up with and/or reinforcing inequalities [].

4.2. Sectoral Specialisation

In terms of policy-making to foster certain sectors over others, there can be an opportunity for a local economy to specialise in a limited set of fast-growing industries rather than diversify, even though, in the long run, specialised economies show faster declines []. The strategy documents we analysed reflect the fact that Local Governments seem to be aiming for short-term growth in priority, as most of them target “key sectors” of potential fast growth. Beyond the zero-sum-game, the non-coordination of local policies carries the risk of synchronising and locking-in local economies, which would reinforce the consequences of a potential sectoral downturn through spatial over-specialisation []. An interesting strategy is, therefore, Liverpool City Region’s, which selects from wider pan-regional Northern Powerhouse capabilities and matches them to the local assets. This seems to be a more convincing strategy, considering the evidence of path-dependency in the process of sectoral diversification []. The effect of the sectoral mix on regional growth and productivity is a classic in the field of regional science. It refers to industrial diversification versus specialisation in relation to trade: highly specialised areas are to perform best when the industry they are specialised in participates in the production of the ongoing industrial cycle. Industrial diversification is thus seen as a better strategy [], especially in the long term, because it creates useful horizontal linkages between sectors and evens out the effects of industrial cycles and downturns. Empirically though, Duranton and Puga [] and Pumain et al. [] remark that specialised and diversified cities co-exist and retrieve advantages from economic interactions. In that respect, the cities most diversified today (Manchester, typically) would have a better prospect when increasing specialisation in advanced manufacturing or the carbon economy than more specialised cities like Sheffield or Liverpool []. Regardless of the initial industrial mix, the specialisation of a local economy has to evolve to keep up with the evolution of the national and global contexts, as risk of a lock-in in subsequent trajectories, as examplified by Los Angeles compared with San Francisco since the 1970s []. On the other hand, the strategy of ‘smart specialization’ utilized in EU cohesion policy [] focuses on identifying region-specific strengths and weaknesses for diversification, while at the same time increasing ‘relatedness’ and linkages within regions and between regions in order to enable long-lasting ‘scale effects’, which is relevant considering the pan-regional nature of many supply chain relationships.

4.3. Theory Versus Empirics of Decentralisation to City-Regions in England

As is visible from the critical analysis of decentralisation discourses and strategies of city regions in England, there is an incongruence between how city regions are supposed to grow, converge, and reach their steady state according to neo-liberal and new economic geography growth theory paradigms underlying policy-making, and what we observe empirically: a zero-sum game that would benefit mostly already privileged regions (large cities rather than smaller ones; ‘devolved’ city regions rather than peripheral areas with no deal; city regions with more fiscal and policy powers, existing resources, and skills). Endogenous growth theories influencing policies of investment in certain types of human capital and sectoral innovation might also fail to help address spatial inequalities because city region economies are not necessarily allowed to evolve from their current endogenous factors, but are modified and acted upon by policy to focus on similar sets of labour, skills, and KIBS (Knowledge Intensive Business Services)-focused economic sectors, putting into question the role and transformation of foundational and industrial economies, for instance. Our results raise concerns that, where agglomeration economies and city regions are favoured along with a ‘foreign aid’ dependency relationship with changing Central Governments, without stable long-term institutions at regional or local level, pan-regional cooperation, or a closer focus on endogenous innovation through ‘smart specialisation’ approaches across the country, the current selective and competitive approach could be detrimental for territorial inequalities. As Martin, Gardiner, and Tyler [] show, differential productivity and employment growth in cities across the United Kingdom show some indication towards regional north–south imbalance, but also illustrate that second and third tier cities have been successful in sustaining an average growth trajectory if they belong to the ‘new town’ category, although less so if they are part of the category characterised by post-industrial legacy and poor housing and transport stock.

A second set of problems regarding the assessment of actual policies delivery and impact at city region level is that the tools and frameworks for evaluation are incomplete and changing. First of all, the data required for measurement and evaluation at city region level are missing or inadequate [], particularly in the areas of economic output, firm-level data, and social mobility. Second, city regions have uneven resources, knowledge, and skills in data analysis and modelling. Third, there is a lack of data sharing and transparency across departmental silos and city regions. Fourth, the way the issues above can foster a reliance on (a) Central Government analysis; (b) external corporate providers who charge for bought in analysis and models that are not transparent; (c) disparate efforts for analysis that do not connect interdependent policy areas such as transport, economics, demographics, or pan-regional complexities; (d) potential to utilise analysis as ‘evidence’ to support certain policy decisions owing to a lack of consistency, benchmarking, or transparency; and (e) issues with evaluating, measuring, and evidencing impact of policies once combined authorities are expected to be self-sufficient from 2020, with a particular risk for a skewing of policy agendas towards more easily measurable (transport, certain economic indicators) factors.

While there are a number of initiatives underway to try and address these issues, such as the Offices for Data Analytics (ODA) [] and Open Data Institute (ODI) nodes, this has been a slow and city regionally disparate process with only one established ODA (Avon and Somerset), and challenges identified in the areas of human resources, technological infrastructure, data, funding, and legal. Furthermore, many existing resources are focused on transport analytics (i.e., Transport Data Initiative, Connected Places Catapult, Transport for West Midlands, Transport for Greater Manchester, Transport for the North).

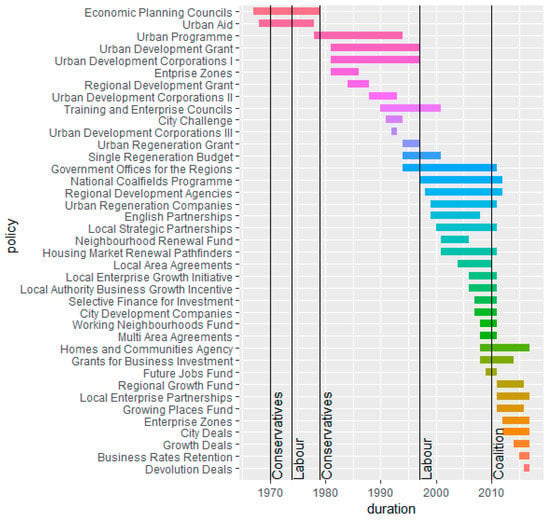

Finally, ‘devolved’ authorities should aim to collect data not only on aggregate output and global productivity, but also on the distribution of income (spatially and by groups), skills, and accessibility if they are to inform inclusive targets rather than productive performance goals only. In general, with growth and convergence processes being dynamical processes, the data necessary to assess them need to be longitudinal by nature. Therefore, we need the institutional frameworks for policy and data collection to have some time consistency and not alter with every change in Central Government in order to build both longitudinal evidence and policy continuity. This temporal consistency has not been met in recent decades in policy-making across England (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

A time line of decentralisation and urban/regional policies in England, along with changes in U.K. Government, 1968–2016 (Source: author research of policy documents).

5. Conclusions

“It is often said, but bears repetition, that by international standards, the UK has some of the largest geographical inequalities in the developed world. Significant inequalities between different areas are evident in almost all aspects of the economy, including productivity, incomes, employment status and wealth. Brexit Britain is a nation made up of cities and towns with contrasting economic trajectories.” [], p. 1.

As the Strategic Economic Plans and the hopes placed in the ‘devolution’ policy agenda suggest, there can be significant advantages to building economic strategies and industrial strategies and managing devolved budgets at the scale of city-regions. Theoretically, integrating the provision of employment, housing, and care at the scale of labour markets might help accounting for local differences between local authorities that are part of the same economy, so that whichever way the activity is spread within the region, the benefits and costs are shared at the level of the combined authority. Similarly, this integration should allow for local decision-makers to better identify and promote local issues in the policy agenda, in contrast with exclusively top-down, centralised approaches.

However, it would be very short-sighted to assume that city-regions in England could be self-sufficient and disconnected from trends operating at larger scales, intra-regional or pan-regional, but also international []. For example, the key sectors promoted by many combined authorities relate to the new specialisation trends aiming to position Britain within the international trade system, and their success depends on national policies and political shifts (such as Brexit). In that respect, Brexit has already brought “into sharp focus so-called ‘left-behind’, whether in reference to people or to places” [], p. 113. Another key feature of the success of the current decentralisation process depends on the continuity of the political geographies created and the lack of continuity in multi-scale institutions. If the combined authorities are bound to the same fate as the RDAs (regional development agencies) before them, that is, a life span of only 11 years (from 1999 to 2010), there is a real risk of wasted resources and missed opportunities for accumulated knowledge and experience.

Ultimately, the focus on city-regions leaves out most of the country out of any deal and political leverage in relationship to higher levels of government and fosters the over-reliance on ‘bidding’ forever different funds. This separate ‘foreign aid’ for social policy approach in ‘lagging regions’ is already visible in the separate ‘Stronger Towns Fund’, and the recent call for additional funding for struggling coastal towns, as well as the U.K.-wide ‘Shared Prosperity Fund’ said to fill the gap of European structural funds, but still lacking detail on extent, distribution, and delivery.

Our analysis shows that the reality of deal-making and negotiations has resulted in the definition of somehow arbitrary geographies for decentralisation competing against each other, although a common set of policies and cooperation could unify the areas included in this particular policy agenda, and avoid an inconsistent, piecemeal approach to addressing inequalities and economic growth by divorcing economic and social policy agendas. By analysing their economic strategy documents quantitatively and qualitatively, we found homogeneity of objectives (higher productivity, higher skills, more and better jobs, similar sectoral focus, connectivity), but a wide diversity of means and resources, both for planning and delivery, and lack of social policy concerns.

We highlighted themes and situations where cooperation rather than competition between local areas would be beneficial (industrial specialisation, skills, transport) and, through the history of alternating area-based policies, highlighted the danger of the reliance on bidding processes for a limited amount of areas instead of the gradual establishment of multi-scale regional and local institutions to deliver, evaluate, and negotiate with Central Government and internationally. In the absence of such coordinated cooperation in policy, and its underpinning analysis (multi-scale, disaggregated, accounting for interdependencies of policy levers, accounting for relationship between social, and economic policy), there is a risk that some strategies will fail and increase the spatial imbalance between regional economies, and fail to deliver higher growth nationally as a consequence.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2413-8851/3/3/90/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S. and C.C.; text mining, C.C.; discourse analysis, C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S. and C.C.; writing—review and editing, C.S. and C.C.

Funding

This research was funded by EPSRC, grant number EP/M023583/1 (‘UK Regions Digital Research Facility’/Urban Dynamics Lab).

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Batty and Alan Wilson for insightful conversations on the matter within the Urban Dynamics Lab project. We also thank anonymous reviewers for their careful evaluation and precise comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Martin, R. The political economy of Britain’s north-south divide. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1988, 13, 389–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.L. The contemporary debate over the North-South divide: Images and realities of regional inequality in late-twentieth-century Britain. Camb. Stud. Hist. Geogr. 2004, 37, 15–43. [Google Scholar]

- McCann, P. The UK Regional-National Economic Problem: Geography, Globalisation and Governance; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sykes, O. Post-geography worlds, new dominions, left behind regions, and ‘other’ places: Unpacking some spatial imaginaries of the UK’s ‘Brexit’ debate. Space Polity 2018, 22, 137–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, B.; Martin, R.L.; Tyler, P. Spatially unbalanced growth in the British Economy. J. Econ. Geogr. 2013, 13, 889–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Pike, A.; Tyler, P.; Gardiner, B. Spatially rebalancing the UK economy: Towards a new policy model? Reg. Stud. 2016, 50, 342–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barca, F.; McCann, P.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. The case for regional development intervention: Place-based versus place-neutral approaches. J. Reg. Sci. 2012, 52, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildreth, P.; Bailey, D. Place-based economic development strategy in England: Filling the missing space. Local Econ. 2014, 29, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaney, J.; Pike, A.; Torrisi, G.; Tselios, V.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. Decentralisation Outcomes: A Review of Evidence and Analysis of International Data; DCLG: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sandford, M. Signing up to devolution: The prevalence of contract over governance in English devolution policy. Reg. Fed. Stud. 2017, 27, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanor, V. Devolution in the United Kingdom; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hazell, R. The English Question. Publius J. Fed. 2006, 36, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aughey, A. The Politics of Englishness; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, J. Devolution in the UK; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pike, A.; Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Tomaney, J.; Torrisi, G.; Tselios, V. In search of the ‘economic dividend’of devolution: Spatial disparities, spatial economic policy, and decentralisation in the UK. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2012, 30, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombes, M. From city-region concept to boundaries for governance: The English case. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 2426–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heseltine, M. No Stone Unturned: In Pursuit of Growth; Department of Business, Innovation and Skills: London, UK, 2013.

- Beel, D.; Jones, M.; Rees Jones, I. Elite city-deals for economic growth? Problematising the complexities of devolution, city-region building, and the (re) positioning of civil society. Space Polity 2018, 22, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackinnon, D. Regional inequality, regional policy and progressive regionalism. Soundings 2016, 65, 141–159. [Google Scholar]

- Pugalis, L.; Townsend, A.R. Rebalancing England: Sub-national development (once again) at the crossroads. Urban Res. Pract. 2012, 5, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, K.; Tewdwr-Jones, M. ‘Disorganised devolution’: Reshaping metropolitan governance in England in a period of austerity. Raumforsch. Raumordn. Spat. Res. Plan. 2017, 75, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HM Government. Cities and Local Government Devolution Bill; HM Government: London, UK, 2016. Available online: https://services.parliament.uk/bills/2015-16/citiesandlocalgovernmentdevolution.html (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- NAO. English Devolution Deals. 2016. Available online: https://www.nao.org.uk/report/english-devolution-deals/ (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- NAO. Funding and Structures for Local Economic Growth. 2013. Available online: https://www.nao.org.uk/report/funding-structures-local-economic-growth-2 (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- Brenner, N. New State Spaces: Urban Governance and Rescaling of Statehood; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tallon, A. Urban Regeneration in the UK; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Capello, R. Regional growth and local development theories: Conceptual evolution over fifty years of regional science. Geogr. Econ. Soc. 2009, 11, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borts, G.H.; Stein, J. Regional Growth and Maturity in the United States. A Study of Regional Structural Change. Swiss J. Econ. Stat. 1962, 98, 290–321. [Google Scholar]

- Chanda, A.; Panda, B. Productivity growth in goods and services across the heterogeneous states of America. Econ. Inq. 2016, 54, 1021–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pumain, D.; Saint-Julien, T.; Sanders, L. Urban dynamics of some French cities. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1986, 25, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. The rise of the “city-region” concept and its development policy implications. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2008, 16, 1025–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.J.; Storper, M. Regions, globalization, development. Reg. Stud. 2003, 37, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; MacLeod, G. Regional spaces, spaces of regionalism: Territory, insurgent politics and the English question. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2004, 29, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, A.E.; Moisio, S. City regionalism as geopolitical processes: A new framework for analysis. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2018, 42, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, A.; Tomaney, J.; Coombes, M.; McCarthy, A. Governing uneven development: The politics of local and regional development in England. In Regional Development Agencies: The Next Generation? Networking, Knowledge and Regional Policies; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 102–121. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J. Ordinary Cities: Between Modernity and Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Etherington, D.; Jones, M. City-regions: New geographies of uneven development and inequality. Reg. Stud. 2009, 43, 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pringle, S.; White, G.; Pates, R.; Cook, J.; Seth, V.; Beaven, R.; Tomaney, J.; Marques, P.; Green, A. Rebalancing the Economy Sectorally and Spatially: An Evidence Review; UK Commission for Employment and Skills: London, UK, 2011; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Di Cataldo, M.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. What drives employment growth and social inclusion in the regions of the European Union? Reg. Stud. 2017, 51, 1840–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachtler, J.; Begg, I. Cohesion policy after Brexit: The economic, social and institutional challenges. J. Soc. Policy 2017, 46, 745–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billing, C.; McCann, P.; Ortega-Argilés, R. Interregional inequalities and UK sub-national governance responses to Brexit. Reg. Stud. 2019, 53, 741–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J. An era of continuing change: Reflections on local government in England 1974–2014. Local Gov. Stud. 2014, 40, 835–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambleton, R. The super-centralisation of the English state–Why we need to move beyond the devolution deception. Local Econ. 2017, 32, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, I. Metropolitanising small European stateless city regionalised nations. Space Polity 2018, 22, 342–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D. Devolution, state restructuring and policy divergence in the UK. Geogr. J. 2015, 181, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, I. Metropolitan and city-regional politics in the urban age: Why does “(smart) devolution” matter? Palgrave Commun. 2017, 3, 17094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E. Triumph of the City; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Oates, W.E. An essay on fiscal federalism. J. Econ. Lit. 1999, 37, 1120–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, P.; Pike, A. ‘Deal or no deal?’ Governing urban infrastructure funding and financing in the UK City Deals. Urban Stud. 2019, 56, 1448–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshire, P.C.; Nathan, M.; Overman, H.G. Urban Economics and Urban Policy: Challenging Conventional Policy Wisdom; Edward Elgar Publishing: Trotschwan, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, S.L. The territorial bases of health policymaking in the UK after devolution. Reg. Fed. Stud. 2005, 15, 501–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J. Political Discourse. In The Handbook of Discourse Analysis; Schiffrin, D., Tannen, D., Hamilton, H.E., Eds.; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. The discourse on language. In Truth: Engagements across Philosophical Traditions; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, N. Discourse and Social Change; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, N. Media Discourse; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hildreth, P.; Bailey, D. The economics behind the move to ‘localism’ in England. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2013, 6, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, B.; Peck, J.; Holden, A. Regional Agencies and Area-Based Regeneration; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- West Midlands Combined Authority. Making Our Mark. 2016. Available online: https://www.wmca.org.uk/media/1382/full-sep-document.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2017).

- Tees Valley Unlimited. Strategic Economic Plan. 2014. Available online: https://www.northyorks.gov.uk/sites/default/files/fileroot/About%20the%20council/Partnerships/Tees_Valley_strategic_economic_plan_%28Apr_2014%29.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2017).

- Leeds City Region LEP; West Yorkshire Combined Authority. Strategic Economic Plan. 2016. Available online: http://investleedscityregion.com/system/files/uploaded_files/SEP-2016-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2017).

- Liverpool City Region & Liverpool LEP. Building Our Future. 2016. Available online: https://www.liverpoollep.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/SGS-Final-main-lowres.compressed.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2017).

- Sheffield City Region. Strategic Economic Plan. 2015. Available online: https://sheffieldcityregion.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Strategic-Economic-Plan-2015-2025.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2017).

- Greater Manchester Combined Authority. Stronger Together. 2013. Available online: https://www.greatermanchester-ca.gov.uk/downloads/file/8/stronger_together_-_greater_manchester_strategy (accessed on 15 January 2018).

- Greater Manchester Combined Authority; New Economy Manchester. Deep Dives Final Report. 2016. Available online: http://www.neweconomymanchester.com/publications/deep-dive-research (accessed on 15 January 2018).

- Bowman, A.; Froud, J.; Johal, S.; Law, J. The End of the Experiment? From Competition to the Foundational Economy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education and Skills. Further Education: Raising Skills, Improving Life Chances; The Stationery Office: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Keep, E.; Mayhew, K.; Payne, J. From skills revolution to productivity miracle—Not as easy as it sounds? Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2006, 22, 539–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mahoney, M.; de Boer, W. Britain’s Relative Productivity Performance: Updates to 1999; National Institute for Economic and Social Research: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chatman, D.G.; Noland, R.B. Do public transport improvements increase agglomeration economies? A review of literature and an agenda for research. Transp. Rev. 2011, 31, 725–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, T. Impacts of Transport Infrastructure on Productivity and Economic Growth: Recent Advances and Research Challenges. Transp. Rev. 2013, 33, 686–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North East Strategic Economic Plan. 2016. Available online: https://www.nelep.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/NELEP-Economic-Analysis.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2018).

- Sissons, P.; Jones, K. Local industrial strategy and skills policy in England: Assessing the linkages and limitations—A case study of the Sheffield City Deal. Local Econ. 2016, 31, 857–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Job Creation and Local Economic Development; OECD: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- BERR. Regional Development Agency Impact Evaluation. 2009. Available online: http://www.berr.gov.uk/whatwedo/regional/regional-dev-agencies/Regional%20Development%20Agency%20Impact%20Evaluation/page50725.html (accessed on 15 July 2018).

- Martin, R.; Sunley, P. Deconstructing clusters: Chaotic concept or policy panacea? J. Econ. Geogr. 2003, 3, 5–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neffke, F.; Henning, M.; Boschma, R. How do regions diversify over time? Industry relatedness and the development of new growth paths in regions. Econ. Geogr. 2011, 87, 237–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L.; Kallal, H.D.; Scheinkman, J.A.; Shleifer, A. Growth in cities. J. Political Econ. 1992, 100, 1126–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duranton, G.; Puga, D. Diversity and specialisation in cities: Why, where and when does it matter? Urban Stud. 2000, 37, 533–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pumain, D.; Paulus, F.; Vacchiani-Marcuzzo, C.; Lobo, J. An evolutionary theory for interpreting urban scaling laws. Cybergeo Eur. J. Geogr. 2006, 343, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.L.; Tyler, P.; Gardiner, B. The Evolving Economic Performance of UK Cities. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/f70c/4e512b81de16aec62b36de1afa783d340f6a.pdf?_ga=2.166531710.1512446734.1565329622-1516131932.1563270104 (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- Storper, M.; Kemeny, T.; Makarem, N.; Osman, T. The Rise and Fall of Urban Economies: Lessons from San Francisco and Los Angeles; Stanford University Press: Palo Otto, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Thissen, M.; Van Oort, F.; Diodato, D.; Ruijs, A. Regional Competitiveness and Smart Specialization in Europe: Place-Based Development in International Economic Networks; Edward Elgar Publishing: Trotschwan, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bean, C. Independent Review of UK Economic Statistics. 2016. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/507081/2904936_Bean_Review_Web_Accessible.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- Nesta. State of Offices of Data Analytics in the UK. 2018. Available online: https://media.nesta.org.uk/documents/State_of_Offices_of_Data_Analytics_ODA_in_the_UK_WEB_v5.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- Carter, A.; Swinney, P. Brexit and the Future of the UK’s Unbalanced Economic Geography. Political Q. 2019, 90, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, G.; Jones, M. Explaining ‘Brexit capital’: Uneven development and the austerity state. Space Polity 2018, 22, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).