The Provision and Accessibility to Parks in Ho Chi Minh City: Disparities along the Urban Core—Periphery Axis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Contextualizing Parks in HCMC

2.1. Legislation and Place-Based Definition of Parks

2.2. How Has the Creation of Parks Evolved over Different Periods of Urbanization?

3. Conceptual Framework

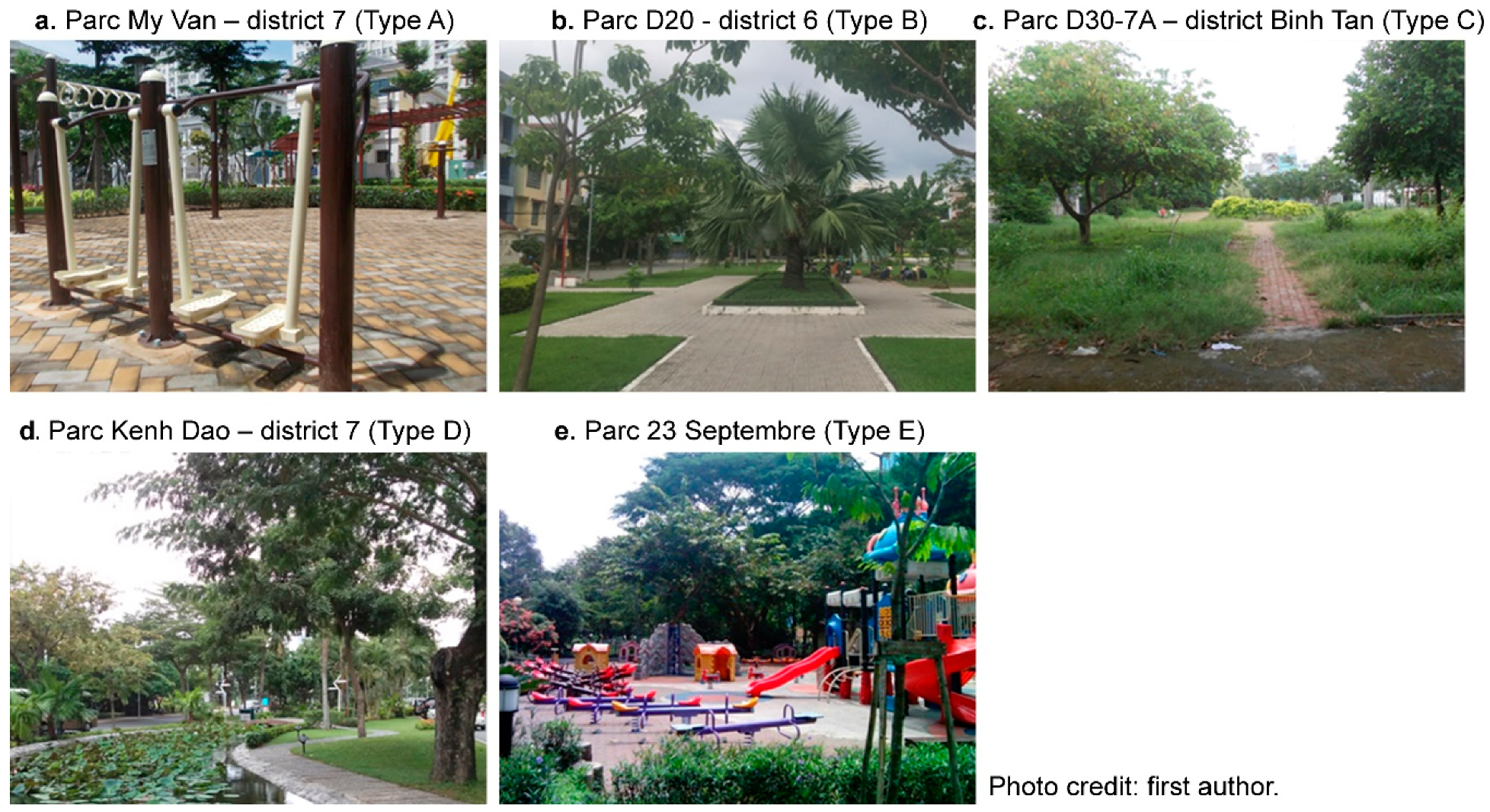

3.1. The Intrinsic Characteristics and Typology of Parks

3.2. Accessibility to Parks

4. Methodology

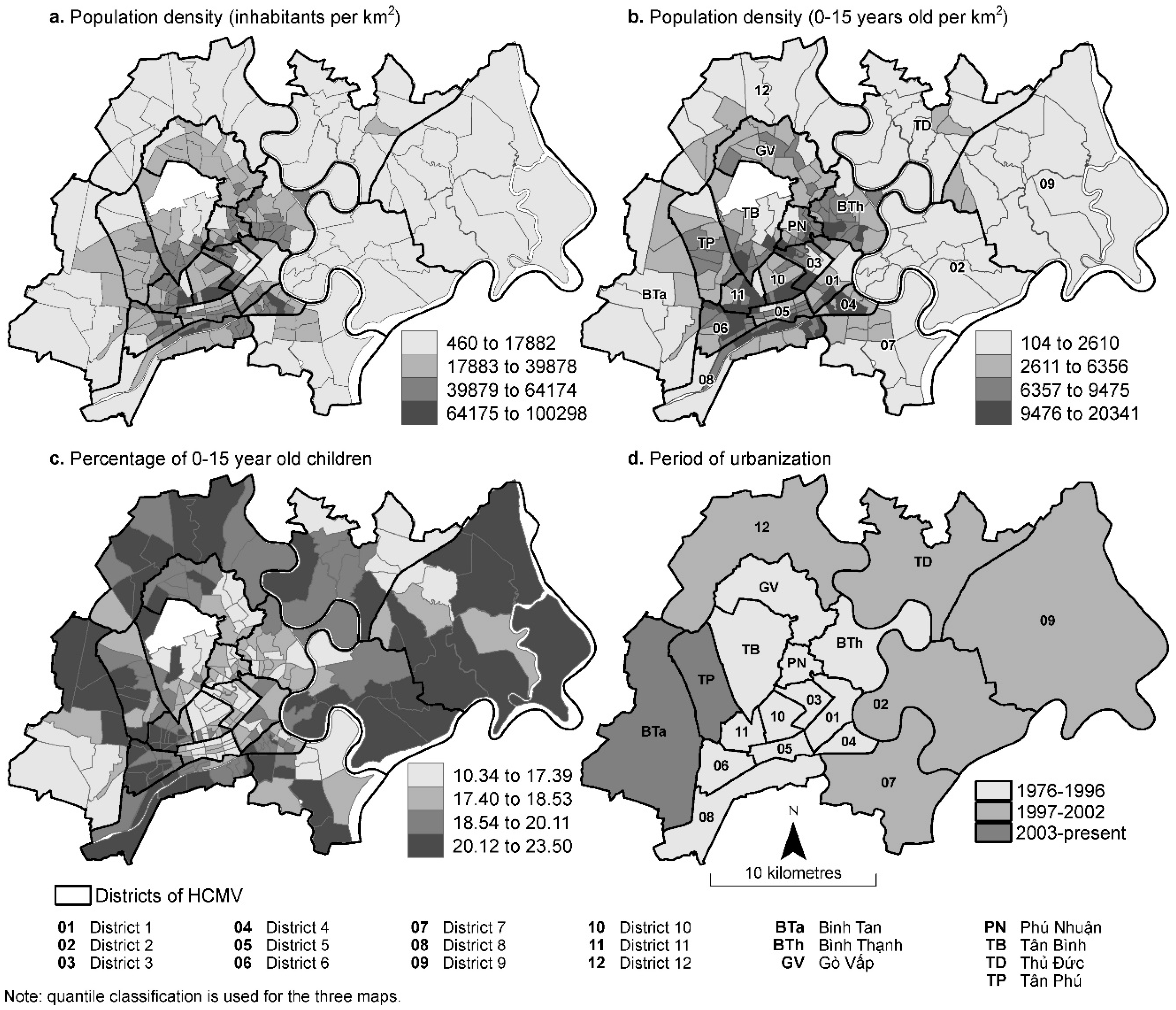

4.1. Study Area and Sociodemographic Data

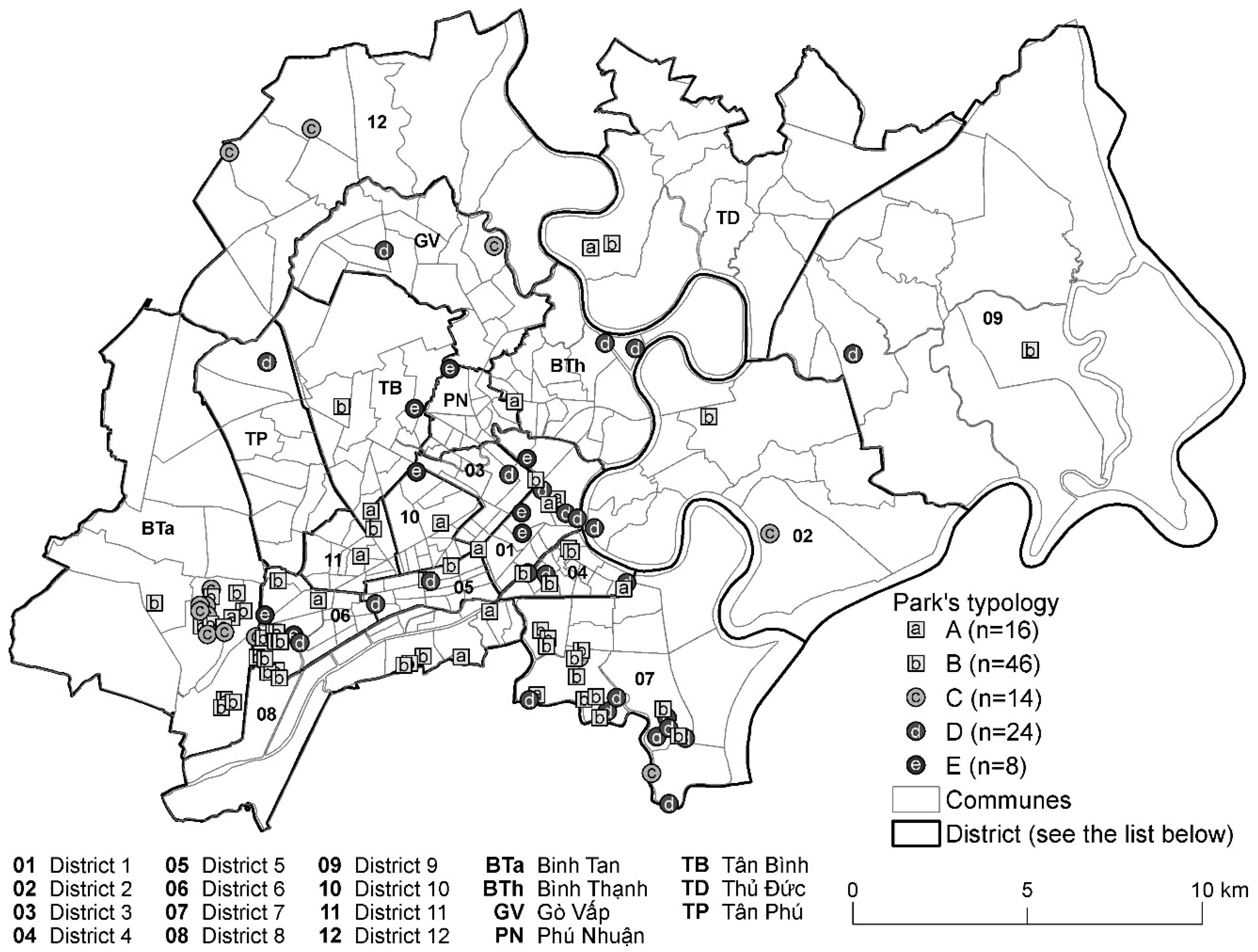

4.2. Data on Parks and Street Network

4.3. Methods of Analysis

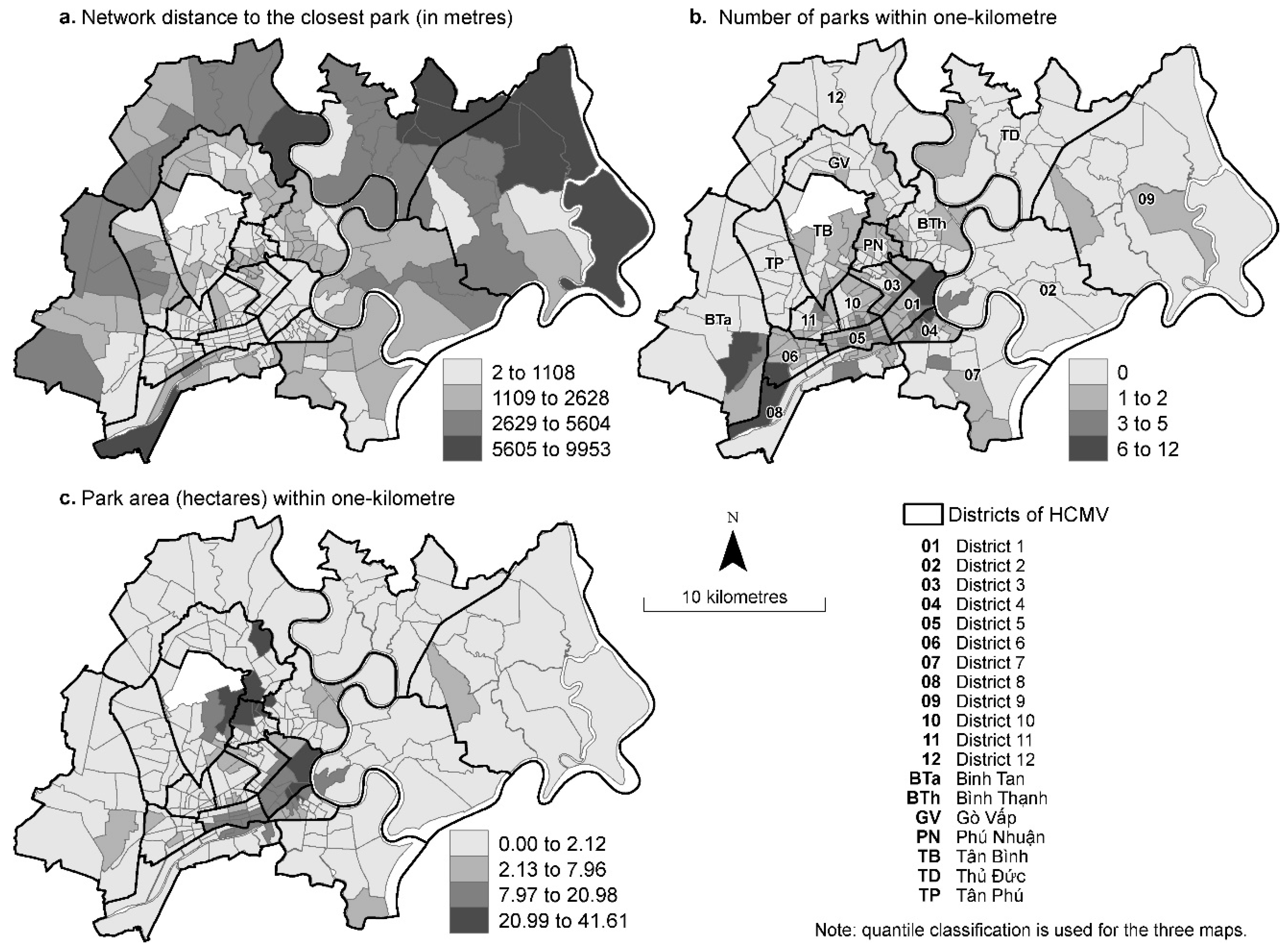

- The distance from the centroid of the residential areas to the closest park (for parks overall and for each type in the typology).

- The number of accessible parks within a 500- to 1000-m radius around the residential areas

- The number of accessible park hectares within a 500- to 1000-m radius.

5. Results

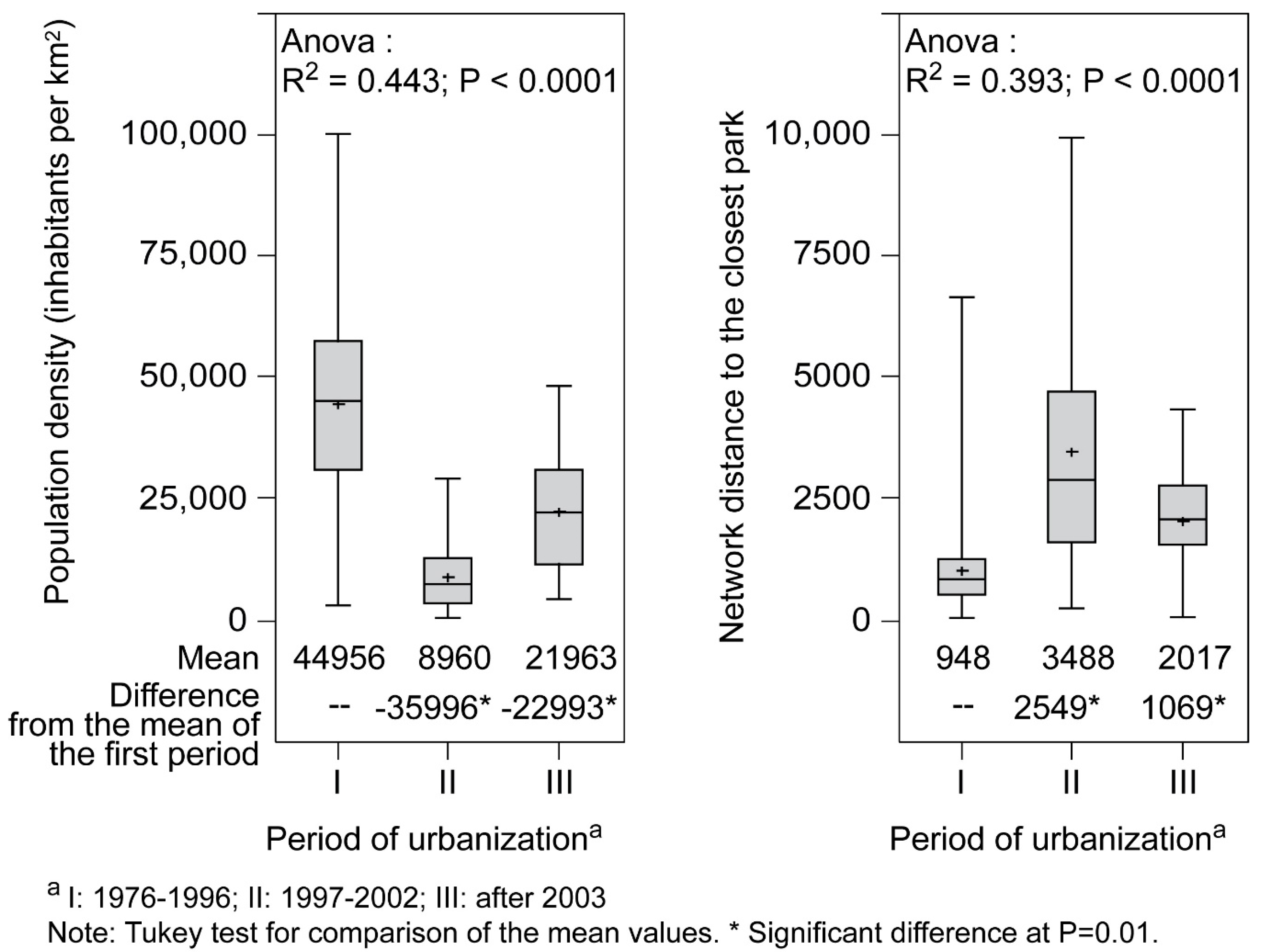

5.1. Typology of Parks and Variations across Space and Time

5.2. Spatial Accessibility of Parks and Variations across Space and Time

5.3. Spatial Accessibility, Population, and Children

6. Discussions and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malek, N.A.; Mariapan, M.; Shariff, M.K.M.; Aziz, A. Assessing the Needs for Quality Neighbourhood Parks. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2011, 5, 743–753. [Google Scholar]

- Smoyer-Tomic, K.E.; Hewko, J.N.; Hodgson, M.J. Spatial accessibility and equity of playgrounds in Edmonton, Canada. Can. Geogr. 2004, 48, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesura, A. The role of urban parks for the sustainable city. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 68, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedimo-Rung, A.L.; Mowen, A.J.; Cohen, D.A. The significance of parks to physical activity and public health—A conceptual model. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haq, S.M.A. Urban Green Spaces and an Integrative Approach to Sustainable Environment. J. Environ. Protect. 2011, 2, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, J.; Wolch, J. Nature, race, and parks: Past research and future directions for geographic research. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2009, 33, 743–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczynski, A.T.; Potwarka, L.R.; Saelens, B.E. Association of Park Size, Distance, and Features with Physical Activity in Neighborhood Parks. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 1451–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apparicio, P.; Cloutier, M.-S.; Séguin, A.-M.; Ades, J. Accessibilité spatiale aux parcs urbains pour les enfants et injustice environnementale: Exploration du cas montréalais. Rev. Int. Géomat. 2010, 20, 363–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolcock, G.; Steele, W. Child-Friendly Community Indicators—A Literature Review; Griffith University, Nathan Campus: Nathan, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond, L.B.W. Street Scenes: Practices of Public and Private Space in Urban Vietnam. Urban Stud. 2000, 37, 2377–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M. Out of Control: Emergent Cultural Landscapes and Political Change in Urban Vietnam. Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 1611–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.L. Urban Green Areas—Their functions under a changing lifestyle of local people, the example of Hanoi. Ph.D. Thesis, Ernst-Moritz-Arndt-Universität Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.B.; Samsura, D.A.A.; van der Krabben, E.; Le, A.D. City profile Saigon-Ho Chi Minh City. Cities 2016, 50, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Vietnam Urbanization Review: Technical Assistance Report; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh, D. The misuse of urban planning in Ho Chi Minh City. Habitat Int. 2015, 48, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.H.; Labbé, D. Spatial logic and the distribution of open and green public spaces in Hanoi: Planning in a dense and rapidly changing city. Urban Policy Res. 2017, 36, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.B.; Krabben, E.V.D.; Samsura, D.A.A. A curious case of property privatization: Two examples of the tragedy of the anticommons in Ho Chi Minh City-Vietnam. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2017, 21, 72–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ADB. Đánh giá đô thị hóa ở Việt Nam (Évaluation de L’urbanisation au Vietnam); World Bank: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bassand, M.; Du, T.T.N.; Taradellas, J.; Cunha, A.; Bolay, J.-C. Métropolisation, Crise Écologique et Développement Durable: L’eau et L’habitat Précaire à Ho Chi Minh-Ville, Vietnam; PPUR Presses Polytechniques: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Harms, E. Luxury and Rubble: Civility and Dispossession in the New Saigon; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- SPV. Thực trạng và định hướng phát triển hệ thống công viên, cây xanh tại Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh (État actuel et orientation de dévelppement du système de parc et plantation à Ho Chi Minh Ville). In Ho Chi Minh Ville: La Société des Parcs et des Végétations Urbaines de Ho Chi Minh Ville; SPV: Ho Chi Minh Ville, Vietnam, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Aldous, D.E. Greening South East Asian Capital Cities. In Proceedings of the 22nd IFPRA World Congress, Hong Kong, China, 15–18 November 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.H. La nature en ville, regards et attentes locaux des habitants d’Hochiminh ville (Vietnam). Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Pau et des Pays de l’Adour, Pau, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- PADDI. L’état actuel de la gestion des espaces verts urbains à Ho Chi Minh Ville. In Atelier la Gestion de Conservation et le Développement des Espaces verts Urbain, 18–22 avril 2011; PADDI: Ho Chi Minh Ville, Vietnam, 2011; p. 126. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Vietnam. TCXDVN 362: 2005 Quy Hoạch Cây Xanh Sử Dụng Công Cộng Trong Các đô Thị—TCTK (Normes en Aménagement D’espaces Verts Public Dans les Zones Urbaines); Ministre de Construction: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2005.

- Han, T.N. Nghệ Thuật Vườn-Công Viên (Art du Jardin et Parc); Edition de Contruction: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kurfürst, S. Redefining Public Space in Hanoi: Places, Practices and Meaning; University of Passau: Passau, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yuen, B. Creating the Garden City: The Singapore Experience. Urban Stud. 1996, 33, 955–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.D. Địa lý Gia-Định-Sài Gòn-Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh (Géographie de Gia Dinh-Saigon-Ho Chi Minh Ville); Editions de Tong Hop: Ho Chi Minh Ville, Vietnam, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- OSH. Available online: http://www.pso.hochiminhcity.gov.vn (accessed on 30 January 2015).

- VNA/CVN. Le Courrier du Vietnam. Available online: http://lecourrier.vn/ho-chi-minh-ville-prevoit-une-croissance-du-pib-de-98-en-2015/208551.html (accessed on 27 November 2015).

- Nguyen, C.D.L. Outils D’urbanisme et Investissements Immobiliers Privés: Fabrication de L’espace Central de Hô Chi Minh-Ville. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Paris-Est, Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Le, T.V. Urbanisation, environment, development and urban policies in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. In Proceedings of the XXV IUSSP International Population Conference Tours, Paris, France, 18–23 July 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, D.; Marsh, T.; Williamson, S.; Derose, K.P.; Martinez, H.; Setodji, C.; McKenzie, T. Parks and physical activity: Why are some parks used more than others? Prev. Med. 2010, 50, S9–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- City of Edmonton. Urban Parks Management Plan; The City of Edmonton: Edmonton, Canada, 2006; Available online: https://www.edmonton.ca/documents/PDF/UPMP_2006-2016_Final.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2019).

- City of Calgary. Open Space Plan; The City of Calgary: Calgary, Canada, 2003; Available online: https://www.calgary.ca/CSPS/Parks/Documents/Planning-and-Operations/open-space-plan.pdf?noredirect=1 (accessed on 28 February 2019).

- DTLR. Improving Urban Parks, Play Areas and Open Spaces; Department for Transport: London, UK, 2002.

- Wendel, H.E.W.; Zarger, R.K.; Mihelcic, J.R. Accessibility and usability: Green space preferences, perceptions, and barriers in a rapidly urbanizing city in Latin America. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 107, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doick, K.J.; Sellers, G.; Castan-Broto, V.; Silverthorne, T. Understanding success in the context of brownfield greening projects: The requirement for outcome evaluation in urban greenspace success assessment. Urban For. Urban Green. 2009, 8, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, J. Controlling the Commons: How Public Is Public Space? Urban Aff. Rev. 2012, 48, 811–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, J.; Harrison, C.M.; Limb, M. People, Parks and the Urban Green: A Study of Popular Meanings and Values for Open Spaces in the City. Urban Stud. 1988, 25, 455–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, D. Start with the Park: Creating Sustainable Urban Green Spaces in Areas of Housing Growth and Renewal; CABE Space: Welwyn Garden City, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Eng, T.-Y.; Niininen, O. An integrative approach to diagnosing service quality of public park. J. Serv. Mark. 2005, 19, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, J.R. Democracy and Public Space; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, D.L. Accessibility to greenspaces: GIS based indicators for sustainable planning in a dense urban context. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 42, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penchansky, R.; Thomas, J.W. The Concept of Access: Definition and Relationship to Consumer Satisfaction. Med. Care 1981, 19, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, K.; Jeong, S. Assessing the spatial distribution of urban parks using GIS. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 82, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abercrombie, L.C.; Sallis, J.F.; Conway, T.L.; Frank, L.D.; Saelens, B.E.; Chapman, J.E. Income and racial disparities in access to public parks and private recreation facilities. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 34, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maroko, A.R.; Maantay, J.A.; Sohler, N.L.; Grady, K.L.; Arno, P.S. The complexities of measuring access to parks and physical activity sites in New York City: A quantitative and qualitative approach. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2009, 8, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talen, E. The social equity of urban service distribution: An exploration of park access in Pueblo, Colorado, and Macon, Georgia. Urban Geogr. 1997, 18, 521–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talen, E.; Anselin, L. Assessing spatial equity: An evaluation of measures of accessibility to public playgrounds. Environ. Plan. A 1998, 30, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, S. Measuring the accessibility and equity of public parks: A case study using GIS. Manag. Leis. 2001, 6, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dony, C.C.; Delmelle, E.M.; Delmelle, E.C. Re-conceptualizing accessibility to parks in multi-modal cities: A variable-width floating catchment area (VFCA) method. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 143, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F. Greener urbanization? Changing accessibility to parks in China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 157, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Wei, X.; Mao, Y. Spatio-temporal disparity between demand and supply of park green space service in urban area of Wuhan from 2000 to 2014. Habitat Int. 2018, 71, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OSG. Vietnam Population and Housing Census 2009. Migration and Urbanization in Vietnam: Patterns, Trends and Differentials; Ministère de Plannification et Investissement—Office Statistique Génerale du Vietnam: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2011.

- Apparicio, P.; Gelb, J.; Dubé, A.S.; Kingham, S.; Gauvin, L.; Robitaille, É. The approaches to measuring the potential spatial access to urban health services revisited: Distance types and aggregation-error issues. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2017, 16, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewko, J.; Smoyer-Tomic, K.E.; Hodgson, M.J. Measuring neighbourhood spatial accessibility to urban amenities: Does aggregation error matter? Environ. Plan. A 2002, 34, 1185–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calińskia, T.; Harabasza, J. A dendrite method for cluster analysis. Commun. Stat. 2007, 3, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sarle, W.S. Cubic Clustering Criterion; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Vietnam. Quy Chuẩn Xây dựng Việt Nam—Tập 1 (Vietnam Building Code. Regional and Urban Planning and Rural Residental Planning); Construction Mdl: Hanoi, Vietnam, 1997; Volume 439/BXD-CSXD.

- Government of Vietnam. Quy Chuẩn Xây dựng Việt Nam (Vietnam Building Code. Regional and Urban Planning and Rural Residental Planning); Construction Mdl: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2008; Volume 1.

- Huynh, D. Phu My Hung New Urban Development in Ho Chi Minh City: Only a partial success of a broader landscape. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2015, 4, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.A. Urban Space Production in Transition: The Cases of the New Urban Areas of Hanoi. Urban Policy Res. 2015, 33, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labbé, D.; Musil, C. Les « nouvelles zones urbaines » de Hanoi (Vietnam: Dynamiques spatiales et enjeux territoriaux. M@ppemonde 2017, 122, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Boone, C.G.; Buckley, G.L.; Grove, J.M.; Sister, C. Parks and People: An Environmental Justice Inquiry in Baltimore, Maryland. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2009, 99, 767–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sister, C.; Wolch, J.; Wilson, J. Got green? addressing environmental justice in park provision. GeoJournal 2010, 75, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J.; Wilson, J.P.; Fehrenbach, J. Parks and park funding in Los Angeles: An equity-mapping analysis. Urban Geogr. 2005, 26, 4–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurfürst, S. Urban Gardening and Rural-Urban Supply Chains: Reassessing Images of the Urban and the Rural in Northern Vietnam. In Food Anxiety in Globalising Vietnam; Ehlert, J., Faltmann, N.K., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2019; pp. 205–232. [Google Scholar]

| Types of Parks | Period of Creation (Approximate) | |

|---|---|---|

| I. Parks and public gardens Public green spaces sometimes well designed with sports facilities, playgrounds for children, benches or maisonettes, etc. | Public garden, linear park | Several periods |

| Large and medium parks that were created since colonial period (i.e., Tao Đàn) | Before 1975 | |

| Cultural parks | 1976–1996 | |

| Neighborhood parks | 1997–2002 and since 2003 | |

| Botanical and Zoological Garden | Before 1975 | |

| II. Public squares Public squares and promenades with vegetation and equipment such as a park. These types of parks are also sometimes used as places of exhibitions or celebration. | Promenade | Since 2003 |

| Large place and square in the city center | Before 1975 | |

| Small square and neighborhood squares | Several periods | |

| III. Theme parks: paid parks | Amusement park | 1976–1996 |

| Tourism complex | 1997–2002 |

| Type | A | B | C | D | E | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Parks Per Type | 16 | 46 | 14 | 24 | 8 | 108 |

| Park Characteristics (Percentage of Parks with Equipment or Facility a) | ||||||

| Equipment | ||||||

| Exercise equipment for adults | 75.0 | 17.4 | 0.0 | 41.7 | 87.5 | 34.3 |

| Path | 75.0 | 78.3 | 35.7 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 78.7 |

| Sliding play structure for children | 31.3 | 2.2 | 7.1 | 4.2 | 75.0 | 13.0 |

| Riding play structure for children | 37.5 | 2.2 | 7.1 | 4.2 | 75.0 | 13.9 |

| Services | ||||||

| Public restrooms with maintenance staff | 50.0 | 6.5 | 0.0 | 45.8 | 100.0 | 27.8 |

| Parking lots for motorcycles with surveillance | 31.3 | 2.2 | 7.1 | 41.7 | 100.0 | 23.1 |

| Restaurant and café | 75.0 | 13.0 | 14.3 | 29.2 | 100.0 | 32.4 |

| Street vendors | 50.0 | 13.0 | 7.1 | 54.2 | 62.5 | 30.6 |

| Natural factor | ||||||

| Decorative plants | 100.0 | 95.7 | 50.0 | 95.8 | 100.0 | 90.7 |

| Pond | 25.0 | 26.1 | 14.3 | 62.5 | 75.0 | 36.1 |

| Tree coverage of park’s total surface area | ||||||

| Less than 10% | 0.0 | 8.7 | 50.0 | 66.7 | 0.0 | 25.0 |

| 10% to 49% | 62.5 | 69.6 | 0.0 | 29.2 | 75.0 | 50.9 |

| 50% and more | 37.5 | 21.7 | 50.0 | 4.2 | 25.0 | 24.1 |

| Lawn coverage of park’s total surface area | ||||||

| Less than 50% | 25.0 | 21.7 | 78.6 | 50.0 | 37.5 | 37.0 |

| 50% to 74% | 6.3 | 34.8 | 7.1 | 16.7 | 25.0 | 22.2 |

| 75% and more | 68.8 | 43.5 | 14.3 | 33.3 | 37.5 | 40.7 |

| Level of maintenance | ||||||

| Deterioration | 50.0 | 43.5 | 100.0 | 20.8 | 0.0 | 43.5 |

| Cleanliness | 81.3 | 69.6 | 7.1 | 91.7 | 100.0 | 70.4 |

| Garbage receptacles | 75.0 | 39.1 | 57.1 | 91.7 | 100.0 | 63.0 |

| Social factor | ||||||

| Park keepers | 31.3 | 15.2 | 14.3 | 75.0 | 87.5 | 36.1 |

| Fixed and mobile security agent | 18.8 | 8.7 | 0.0 | 70.8 | 100.0 | 29.6 |

| Pavilions | 6.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 37.5 | 9.3 |

| Bancs | 81.3 | 39.1 | 0.0 | 66.7 | 100.0 | 50.9 |

| Fee-based games | 6.3 | 2.2 | 7.1 | 4.2 | 87.5 | 10.2 |

| Space for collective activities | 31.3 | 4.3 | 0.0 | 37.5 | 100.0 | 22.2 |

| Size of parks | ||||||

| Less than one hectare | 100.0 | 95.7 | 78.6 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 66.7 |

| 1 to 4.99 hectares | 0.0 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 91.7 | 0.0 | 21.3 |

| 5 hectares and more | 0.0 | 2.2 | 21.4 | 4.2 | 100.0 | 12.0 |

| Count Row Percent Column Percent | A | B | C | D | E | Row Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1976–1996 | 12 | 22 | 2 | 13 | 8 | 57 |

| 21.05% | 38.60% | 3.51% | 22.81% | 14.04% | ||

| 75.00% | 47.83% | 14.29% | 54.17% | 100.00% | 52.78% | |

| 1997–2002 | 2 | 14 | 5 | 10 | 0 | 31 |

| 6.45% | 45.16% | 16.13% | 32.26% | 0.00% | ||

| 12.50% | 30.44% | 35.71% | 41.67% | 0.00% | 28.70% | |

| 2003–present | 2 | 10 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 20 |

| 10.00% | 50.00% | 35.00% | 5.00% | 0.00% | ||

| 12.50% | 21.74% | 50.00% | 4.17% | 0.00% | 18.52% | |

| Column Total | 16 | 46 | 14 | 24 | 8 | 108 |

| 14.82% | 45.59% | 12.96% | 22.22% | 7.41% |

| Accessibility Measure | Statistics Weighted by the Total Population | Statistics Weighted by the Population under 15 Years Old | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moy. | Min. | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Max. | Moy. | Min. | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Max. | |

| Minimum distance according to type of park a (in meters) | ||||||||||||

| All | 1879 | 2 | 713 | 1304 | 2533 | 9953 | 1890 | 2 | 737 | 1313 | 2570 | 9953 |

| A | 4097 | 2 | 1400 | 2742 | 5830 | 22,325 | 4192 | 2 | 1414 | 2768 | 6373 | 22,325 |

| B | 3381 | 96 | 1337 | 2494 | 4476 | 12,411 | 3418 | 96 | 1361 | 2498 | 4592 | 12,411 |

| C | 5139 | 32 | 3050 | 4918 | 6532 | 18,261 | 5101 | 32 | 3050 | 4768 | 6467 | 18,261 |

| D | 3030 | 8 | 1516 | 2568 | 3964 | 15,541 | 3029 | 8 | 1510 | 2568 | 3952 | 15,541 |

| E | 4548 | 226 | 1745 | 3263 | 6042 | 22,683 | 4613 | 226 | 1819 | 3296 | 6042 | 22,683 |

| Number of parks | ||||||||||||

| 500 m | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 6.00 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 6.00 |

| 1000 m | 0.75 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 12.00 | 0.72 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 12.00 |

| Number of hectares of parks | ||||||||||||

| 500 m | 1.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 41.61 | 0.99 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 41.61 |

| 1000 m | 2.49 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.75 | 41.61 | 2.36 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 41.61 |

| Demographic Variable | Reticular Distance to the Nearest Park by Type a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | All | |

| Population density | −0.63 | −0.45 | −0.08 | −0.45 | −0.53 | −0.39 |

| Percentage of children under 15 years old | 0.23 | 0.14 | −0.18 | 0.08 | 0.38 | 0.22 |

| Density of children under 15 years old | −0.62 | −0.45 | −0.11 | −0.45 | −0.49 | −0.38 |

| Demographic Variable | Park Area (Hectares) | Number of Parks | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within 500 m | Within 1000 m | Within 500 m | Within 1000 m | |

| Population density | 0.04 | 0.28 | 0.04 | 0.25 |

| Percentage of children under 15 years old | −0.12 | −0.21 | −0.14 | −0.25 |

| Density of children under 15 years old | 0.03 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 0.23 |

| Network Distance to the Nearest Park by Type a | Park | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urbanization b | Weight | All | A | B | C | D | E | N | ha |

| 1976–1996 | Total population | 1034 | 2483 | 2551 | 4833 | 2029 | 2521 | 1.01 | 4.15 |

| 1997–2002 | Total population | 3642 | 8001 | 5794 | 6737 | 4772 | 9581 | 0.12 | 0.17 |

| 2003–present | Total population | 2134 | 3764 | 2587 | 3749 | 3868 | 3925 | 0.79 | 0.21 |

| 1976–1996 | 0–14 years old | 1048 | 2522 | 2554 | 4804 | 2022 | 2586 | 1.00 | 3.97 |

| 1997–2002 | 0–14 years old | 3569 | 8132 | 5817 | 6554 | 4744 | 9541 | 0.13 | 0.18 |

| 2003–present | 0–14 years old | 2218 | 3898 | 2712 | 3891 | 3867 | 4035 | 0.63 | 0.17 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hoang, A.T.; Apparicio, P.; Pham, T.-T.-H. The Provision and Accessibility to Parks in Ho Chi Minh City: Disparities along the Urban Core—Periphery Axis. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3010037

Hoang AT, Apparicio P, Pham T-T-H. The Provision and Accessibility to Parks in Ho Chi Minh City: Disparities along the Urban Core—Periphery Axis. Urban Science. 2019; 3(1):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3010037

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoang, Anh Tu, Philippe Apparicio, and Thi-Thanh-Hien Pham. 2019. "The Provision and Accessibility to Parks in Ho Chi Minh City: Disparities along the Urban Core—Periphery Axis" Urban Science 3, no. 1: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3010037

APA StyleHoang, A. T., Apparicio, P., & Pham, T.-T.-H. (2019). The Provision and Accessibility to Parks in Ho Chi Minh City: Disparities along the Urban Core—Periphery Axis. Urban Science, 3(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3010037