Abstract

The late 2000s witnessed a wide diffusion of innovative workplaces, named coworking spaces, designed to host creative people and entrepreneurs: the coworkers. Sharing the same space may provide a collaborative community to those kinds of workers who otherwise would not enjoy the relational component associated with a traditional corporate office. Coworking spaces can bring several benefits to freelancers and independent workers, such as knowledge transfer, informal exchange, cooperation, and forms of horizontal interaction with others, as well as business opportunities. Moreover, additional effects may concern the urban context: from community building, with the subsequent creation of social streets, and the improvement of the surrounding public space, to a wider urban revitalization, both from an economic and spatial point of view. These “indirect” effects are neglected by the literature, which mainly focuses on the positive impact on the workers’ performance. The present paper aimed to fill the gap in the literature by exploring the effects of coworking spaces in Italy on the local context, devoting particular attention to the relation with social streets. To reach this goal, the answers (236) to an on-line questionnaire addressed to coworkers were analysed. The results showed that three quarters of the coworkers reported a positive impact of coworking on the urban and local context, where 10 out of 100 coworking spaces developed and/or participated in social streets located in Italian cities, but also in the suburban and peripheral areas.

1. Introduction

In the context of a rising sharing economy and the growing knowledge of workers, the last two decades have witnessed the worldwide spread of the phenomenon of new workplaces known as “coworking spaces” (hereinafter CSs) [1]. One of the main strengths of CSs is they build a sense of community amongst the people working there (Coworkers-CWs), which may enable them to benefit from knowledge transfer, informal exchange, cooperation, and forms of horizontal interaction with others, as well as business opportunities [2,3,4,5,6,7]. Some studied have discussed the urban effects of CSs, including: (i) the improvement of the surrounding public space; (ii) the wider urban revitalization (from an economic and a spatial point of view); (iii) community building, with the subsequent creation of social streets (hereinafter SoSts) [8].

First founded in Italy, the concept of SoSts is a bottom-up approach to create communities at the neighbourhood level with the aim of shifting from online virtual meetings (on Facebook) to offline face to face gatherings in public spaces (such as the streets). Recently, CSs have shown interest in collaborating with such informal organizations to tackle social isolation and to create communities between coworkers and the residents living in the same neighbourhood.

Though the first CS was introduced in 2005, it is only in the past few years that we have seen a growing interest amongst scholars of varied disciplines to study and explore this concept as an alternative workplace, with respect to the traditional office space (see the Section 2.1). The term coworking was used more frequently before, often in contributions concerning business trends (Botsman & Rogers, 2011; Ferriss, 2009; Hunt, 2009). Regarding the SoSt, created in 2013; apart from some surveys that track the spread of these communities in Italy, no particular study has conducted a structured study to explore the importance and effects of the SoSt at a local urban scale. Both the phenomena of the CSs and SoSt are still nascent and need exploration through more in-depth studies that focus on relevant case-studies.

Within this framework, the present paper aims to contribute to the emergent literature on CSs and to fill the gap on the topic of collaboration between such workplaces with community-making organizations such as the SoSt. In particular, this study explores the local urban effects of CSs in Italy, with a particular focus on their interactions with the SoSts in Milan. Accordingly, to reach this goal, the results of the qualitative and quantitative research is described. On the one hand, data on CSs in Italy comes from the FARB research project—exploring the new workplaces, coworking spaces and makerspaces, in Italy—which has developed:

- -

- an original georeferenced database on all CSs in Italy, with detailed information concerning the office spaces, provided services, etc.

- -

- an on-line questionnaire to coworkers, with 236 responses.

Data on the SoSts, on the other hand, was mainly collected through desk research and on-site field data for specific cases in Milan.

The effects of CSs at the local level may include: (i) the extension of daily and weekly cycles of use (i.e., evening and night activities, weekend activities); (ii) the episodic participation in strengthening community ties (i.e., SoSts); (iii) the revitalization of existing retail and commercial activities; and (iv) the strengthening mini-clusters of creative and cultural productions [8]. The results of the empirical analysis showed that three quarters of the CWs reported a positive impact of the CS on the urban and local context, where 10 out of 100 CSs developed and or collaborated with SoSts streets located in several Italian cities, as well as in urban, suburban, or peripheral areas.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 outlines the origins and main aspects of the two phenomena: CS and SoSt. The empirical insights on CSs in Italy, and on the relationship between the SoSt in the Lambrate neighbourhood (Milan) are presented in Section 3. The conclusion (Section 4) summarizes the findings, whilst introducing future lines of research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. New Forms of Workplace: The Rise of Coworking Spaces

Technological advancements and information and communication technologies (ICTs) have led to opportunities for changing the forms and nature of work, i.e., how, when, and where to perform various work activities [9]. Therefore, many individuals tend to work remotely as independent or freelance workers to make use of the autonomy and flexibility in space and time [10]. However, as shown in some studies, such workers may experience the feeling of isolation [11,12]. The knowledge economy is based on a highly skilled labour force and knowledge workers, and it has led to the rise of a creative class (Florida, 2002), which is drawn to the opportunities and amenities found in urban centres, and the demand for more collaborative and decentralized working trends [2]. These are some of the reasons that have given rise to the need for new forms of workplaces, such as coworking spaces, which are equipped with the necessary technological infrastructures, the ICTs, that favour high flexibility and hybridization, where people can work outside regular traditional office working hours. In this regard, some scholars argue that the borders between private homes, productive spaces, and socializing sites are becoming less evident [13,14].

Here, it is worth underlining the difference between such new emerging workplaces and the phenomenon of ‘third places,’ introduced by the sociologist Oldenburg [15], as informal social meeting places that are separate from the two conventional environments of the home (the first place) and the productive workspace/office (the second place). He argues that third places, such as community centres, cafes, bars, malls, libraries, parks, etc., are anchors of communities that may facilitate and foster broader, more creative interaction; hence, they are important for societies, public involvement, and the creation of a sense of place. In this regard, Martins [16] (p. 142) also adds that “The coffee shop, the pub or the park are more than spaces for pursuing creative lifestyles; they are part of a complex network of spaces that are used, and essential, for digital production”. Others have asserted that such public spaces, which are not planned as official working environments, are increasingly being occupied as spaces for work [17].

Some scholars position new types of workplaces, such as CSs, within the wider collection of ‘third spaces for work, learning and play’, which may facilitate formal productive activities within informal social interactions, often accompanied with direct/indirect learning programmes and the use of new technologies [18]. Unlike traditional third places such as libraries and bars, CSs are designed and planned specifically as facilitators for work by providing the basic necessities such as desk, technological needs (namely wifi), meeting rooms, and other equipment in order to develop their own network. CSs, therefore, offer geographical proximity and non-hierarchical relationships, which may create socialization and, consequently, business opportunities [2].

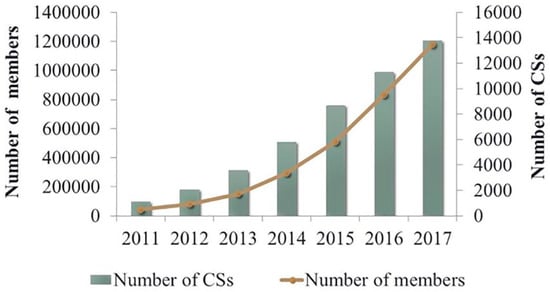

Since the birth of CSs in 2005, in the US, such sharing workplaces have spread worldwide over the last decade, and the coworking movement is reported to have roughly doubled in size each year since 2006 (Figure 1). In the growing literature on CSs, it is stressed the role of coworking in establishing a community; ensuring a quality of working behaviour as ‘working-alone-together’, which involves a shared working environment and independent working activities [2,19,20,21].

Figure 1.

The number of CSs and their members (coworkers) worldwide (2011–2017). Source: own elaboration based on data from: 2017 Global CoWorking Survey, www.deskmag.com.

In the more recent literature, CSs are regarded as potential “serendipity accelerators” [3] (p. 8) designed to host knowledge workers, the creative class, and entrepreneurs, who endeavour to break isolation and to find a convivial environment that may favour meeting and collaboration [3]. Besides, CSs is considered as a “phenomenon that happens in shared, collaborative workspaces in which the emphasis is on community, relationship, productivity and creativity” [22] (p. 4). In other words, it provides localized spaces where independent professionals work while sharing resources and their knowledge with the rest of the community [23].

Furthermore, as mentioned beforehand, trends such as the rise of the digital economy, advancements in information and communication technologies, growth in entrepreneurship, freelance and teleworkers demands new workplaces and collaborative coworking culture, which enables the formation of an economy that may support community and innovation [24]. In this regard, Merkel [25] (p. 122) underlines that “as flexibly rentable, cost-effective and community-oriented workplaces, coworking spaces facilitate encounters, interaction and a fruitful exchange between diverse work, practice, and epistemic communities and cultures”. Nevertheless, studies have also argued the fact that simple physical proximity of coworkers may not necessarily promote interaction and collaboration towards a sense of community [26], yet instead other factors such as social animation, engagement and enrolment among coworkers are seen essential [6]. Others have also confirmed the importance of CSs to embark upon collaborative activities in order to ensure highly productive working environment, considering the opportunities made available by these spaces, such as social interaction, networking and knowledge sharing [27].

Some scholars in the field of urban studies have made an attempt to investigate the location patterns and effects of CSs on the urban environment [8]. Findings of their empirical study on 68 CSs located in Milan shows that their location patterns resemble the service industries in urban areas, and mainly the so-called ‘creative clusters’. Moreover, this research sheds light on some of the urban effects of CSs, such as the participation of CWs to local initiatives, contribution to urban revitalization trends, and the micro-scale physical transformations. Regarding the potential impact of CSs on the local urban context, a very recent publication on mid-sized cities in Ontario [28] has shed light on the importance of innovative, collaborative and inclusive approaches of such workplaces to local economic development; since they provide affordable, well-resourced spaces for new organizations and businesses, yet also for freelance workers and local entrepreneurs.

Although the academic literature on CSs is expanding, further research and more detailed studies are still needed to explore the dynamics of CSs at the local level, and more specifically to understand their interaction and role in neighbourhood communities. This paper, hence, aims to fill the gap in the literature by focusing on these aspects concerning the insertion of CSs within the new made-in-Italy phenomenon: Social Streets, which is explored in the following sections.

2.2. From A Facebook Group to a Neighbourhood Community: The Phenomenon of Social Streets

Gaspar and Glaeser [29] argue two opposing effects of improvements in telecommunications technology on face-to face interactions: they may decrease and become electronically (via social network services for instance), or in contrary the contacts may increase thanks to the technology. So, it is true that people tend to interact more virtually and electronically and may need physical places to meet. SoSts are, therefore, a new and innovative answer that goes exactly in this direction: “tame places, make them familiar” (Marc Augé’s preface for the report on SoSts in Milan:"Vicini e connessi" [30]). A SoSt is born from the desire of the residents of an anti-social street to seek and create participatory and collective-meeting points in their neighbourhood, i.e., places to meet and to know each other; to do things together and help one another.

In cities, people have always needed places to meet one another and to be able to recognize urban elements, such as squares, public places, parks, and roads. Yet, cities, often, end up in creating ghetto neighbourhoods (gated communities) where cars dominate; people are isolated in their apartments and public spaces are increasingly hostile and unused. In recent years, however, a new kind of public space, called the SoSt, was created from the bottom, by the residents themselves [31].

One can consider the SoSt as “new places”, where the point of reference is the public space, here is the street and the spaces around it. Unknown people who live on an anonymous street begin to get to know and meet one another; collaborate to transform the neighbourhood into a social place that is rich in relationships. Social networks are the perfect platform to trigger these ties between unknown neighbours. Therefore, people may become familiar with others easily through overcoming the initial threshold of the face-to-face encounter with strangers; online knowledge and collaboration quickly transforms into a real community that lives and regenerates the neighbourhood.

The idea of “Social Street” in Italy originates from the experience of the Facebook group “Residents in Via Fondazza-Bologna”, born, in September 2013, from the observation of the general impoverishment of social relationships, which causes feelings of loneliness and loss of sense of belonging; urban degradation and lack of social control of the territory (See the website www.socialstreet.it). As a form of neighbourhood community, the SoSt aspires to promote good neighbourly practices; to socialize with the neighbours on their own way, and to establish links, share needs, exchange skills and knowledge; to carry out projects of common interest and gain all the benefits that derive from greater social interaction. SoSt may, therefore, allow people to socialize and to motivate virtuous circles of reciprocity and trust. The requisites to consider a SoSt is different, would be the spatial proximity [32]: the SoSt are served to spatially connect people, in limited portions of the district (the street or the neighbourhood); other main features are: social innovation, social inclusion and groundless.

The definition of SoSt is unique, but its characteristics may vary by: the number of participants, size of the neighbourhood, and the people’s level of participation and commitment to the group. The first phase of launching a SoSt entails creating a neighbourhood based group on Facebook. This is the first step in which people may get in touch on the digital platform, asking for information and help from their online neighbours. The second step is the offline meeting, in which the neighbours decide to socialize even outside the virtual group page, to build links that are defined as “real”. In the third phase (defined as “virtuous”), they can move from simple knowledge seeking to a real collaboration with common interests or utilities. In this phase, the neighbours collaborate for the sake of their area’s common goods; for instance, arrangement of uncultivated flowerbeds, interventions on degraded areas or small redevelopment actions, etc.

The idea of the term “social street” was coined by the founder, joining the two key concepts: social network and place of real socialization (the street). The transition from the group of via Fondazza to the birth and diffusion of SoSts has necessitated the creation of a website to communicate, collect and disseminate experiences and good practices of the SoSt (see http://www.socialstreet.it/).

3. Empirical Insights

3.1. Exploring Coworking Spaces in Italy

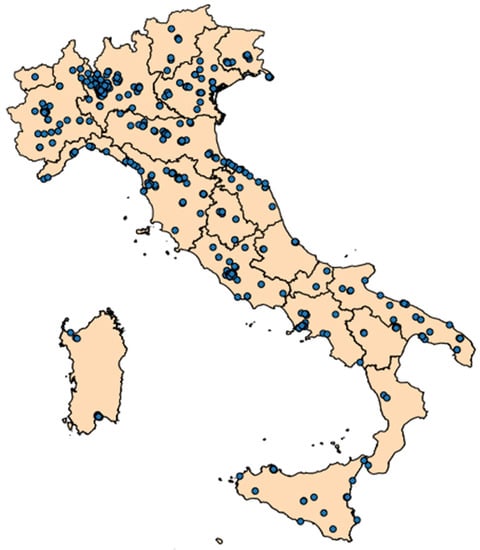

Within the FARB research project (entitled “New working spaces. Promises of innovations, effects on the economic and urban context”, which has been funded by Department of Architecture and Urban Studies (DAStU)—Politecnico di Milano) exploring new workplaces—coworking spaces and makers spaces—in Italy, the CSs located in Italy have been identified and mapped: total number of 549 CSs are recorded, of which about 51% are located in the Italian metropolitan cities, with Milan (97), Rome (46), Turin (18), and Florence (16) hosting about half of them (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The location of CS in Italy at the beginning of 2018. Source [7].

Besides, an on-line questionnaire has been sent to the coworkers (via the coworking managers). By July 2017, 236 coworkers have answered, from 137 CSs located in 19 Italian cities: 44% female and 56% male; 52% belong to the age group 36–50, followed by coworkers aged between 25 to 35 (38%), over 51 (9%), and those between aged 19–24 (1%).

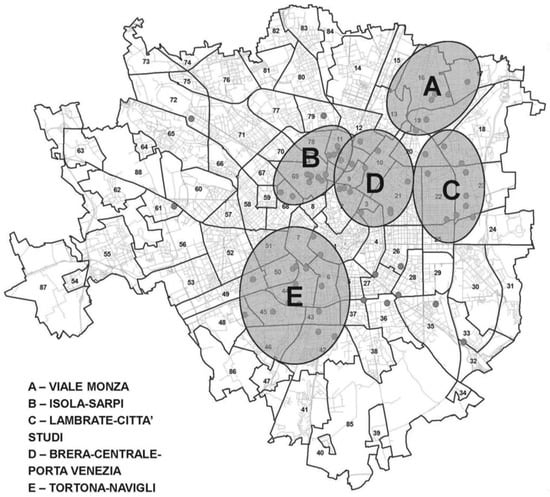

As mentioned beforehand, the city of Milan hosts the majority of CS (97), which are agglomerated into five areas (Figure 3). The main location determinants of CS in urban areas, as already discussed by Mariotti et al. [8]:

Figure 3.

The agglomeration of CS in Milan. Source [8] (p. 10).

- (1)

- the high density of business activities, which is a proxy for urbanization and localization economies, as well as market size;

- (2)

- the proximity to universities and research centres, which is a proxy for the availability of skilled labour force and business opportunities;

- (3)

- the presence of a good local public transport network, which is a proxy for the level of accessibility.

3.2. The Growing Number of Social Streets in Italy

From the studies, it was estimated that in the last quarter of 2013, just after the launch of the first SoSt, the total number rose to 140, and then up to 454 in January 2017 [30]. From the studies carried out by the SoSt observatory, the largest number is located in North-West 143 (34%) and North-East 133 (32%), we find 78 (19%) in the Centre, 36 (8%) in the South and Islands 30 (7%) [30]. Currently, in Italy there are a total number of 100,000 SoSt members (streeters), of which about 50% are residing in Milan.

This phenomenon is also emerging outside national borders: in January 2018 the SoSt observatory surveyed SoSts in Warsaw, Trondheim, Nelson Glenduan, Madison, Amsterdam, Lisbon, Montreal and Agudos [30]. In some cases, the SoSts were established from people visiting Italy who participated in one of them and then repeated this experience in their country.

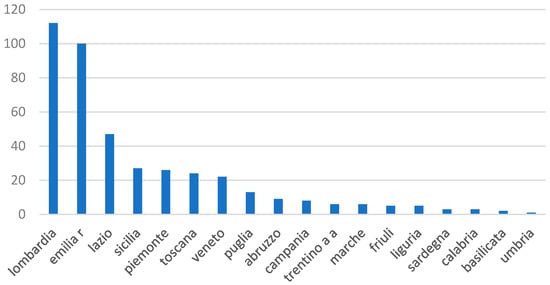

The difference in numbers between the North and South can be associated with the technological development, and social innovation propensity in the northern areas. Regarding the number of SoSt, Lombardy leads with 112, immediately followed by Emilia Romagna with 100, then Lazio with 47 (Figure 4). Certainly because these are the regions that host the most important cities; in fact in Milan there are 77 SoSt, followed by Bologna with 67 and Rome with 34.

Figure 4.

The location of Social Streets in the Italian provinces. Source: authors’ elaboration from the reference [30].

Between January 2017 and January 2018, some cities have experienced a positive trend (Milan, Bologna and Rome), others have remained stable, while some have even closed their SoSt. Milan remains in the lead also for the number of followers in the Facebook page, about 50,000; once again followed by Bologna with 13,000 members. Yet, not always the number of SoSt corresponds to the number of streeters. For example, Novara and Brescia both have two SoSts, but the first has 5 members, while the second has almost 1000.

Milan is the capital of northern Italy, and the financial and economic core of the country. Many people have chosen to settle in this city, and among them there are people who do not appreciate the coldness of social relationships. But if you get to know your neighbours, and you could rely on them for little or important things, this could also improve your quality of life.

Milan is, hence, the right city for the expansion of this phenomenon, as it has always been characterized by innovation, creativity and development [33]. Through the expansion of the phenomenon, in the city there has been a growth boom in 2014, with the opening of 39 SoSt. As for other cities of the province, there are a total number of 10 SoSt. Indeed the numbers are significantly lower than Milan, but still significant.

In January 2018, 1760 members are registered in the SoSt groups, and some of them have confirmed as points of reference for the district, while we must remember that not all of them are active in the same way; not all are active both online and offline; senior citizens are not always the most active while count as the highest number of subscribers to Facebook groups.

Among the social networks in Milan, the one with the highest number of people registered is “San Gottardo-Meda-Montegani” with 7550 members, followed by Nolo Social District which, despite being the youngest, already has 5579 members. The spatial distribution within the city is not homogeneous: the SoSt have no administrative boundaries, they are fluid groups that by definition connect the neighbours of a street and their surroundings and are linked to the more social characteristics of some areas rather than others; such as the presence of parks or meeting places (namely Darsena, Navigli and Duomo).

3.3. The Effects of CSs on the Local Context and Collaboration with SoSts

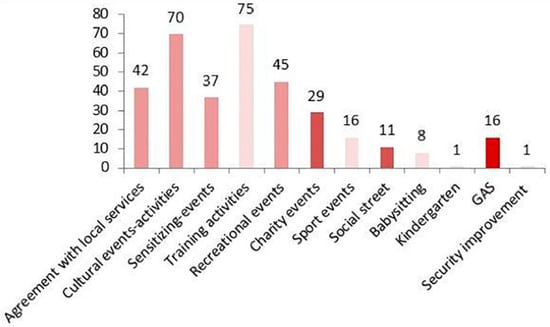

As concerns the effects of CS on the urban environment and the neighbourhood, the answers of the 236 coworkers emphasise the agreements with local services as the most significant impact on the surrounding neighbourhoods, which can contribute, directly or indirectly to a degree of urban regeneration (see also [34]). Moreover, other activities which may show a potential higher impact on the neighbourhood are: organizing charity events, participating at a SoSt and belonging to an Ethical Purchasing Group (Gruppo di Acquisto Solidale—GAS) (Figure 5). These activities reveal the importance of CS as social and cultural hubs, in some cases with specific welfare-related activities such as childcare [33].

Figure 5.

Activities OFFERED by the CSs. Source: [33].

3.4. The Case of “Lambrate-Milano-Social Street”

Out of a total number of 97 CSs in Milan, 19 are located in areas of SoSt that give rise to initiatives of different types within the district (other than to their coworkers). An example is provided by the case of Lambrate Social Street in Milan, which will be discussed in the next section.

In the last twenty years, the Lambrate neighbourhood, located in the Eastern part of the city, has experienced an urban regeneration process partly driven by: design, art, new spaces for work (such as CSs) open air at the markets, music and the desire of its inhabitants to live in a “new” neighbourhood. Since 2010, Lambrate hosts events of the Fuorisalone related to the Salone del Mobile (Milan Design Week). In recent years, a virtuous collaboration between coworkers, inhabitants and entrepreneurs of the district has been consolidated, which is progressively leading the area towards a process of urban regeneration “from below”.

In 2015, with a few members on the Facebook page (all being neighbours), the SoSt Residents in Lambrate—Milan was formed. It has grown exponentially over the years, especially at the first auto events organized in Piazza Rimembranze, the main square of the district, a roundabout that was poorly used as a parking space and surrounded by car traffic. The benches were often occupied by families of nomads and homeless people, being deserted by the inhabitants of the neighbourhood as an unsafe place. The square’s liveability issues was strongly felt by the residents; one of the main demands that emerged during the first meeting was, indeed, that of giving back life to the square.

Therefore, the idea of creating a shared garden was born, with the help of many residents who came on a Saturday morning in the square with plants, flowers, boxes, brooms and black bags to clean up. The children painted the boxes, prepared and spread seeds bombs. With the help of some creative designers and architects in Lambrate, the neighbours have built a beautiful garden in the square. Within a few months, the shared garden has become an important place for evening aperitives, to get to gather and communicate with one another.

These series of events has given a lot of visibility to the SoSt, the number of members has surged. Even other associations in the area have contacted them to make a network. Today the ViviLambrate Group—which was founded in October 2014 in a spontaneous and self-organized form, by a set of organizations and associations based in the Municipality 3, networked with the aim of promoting cultural and social initiatives to revitalize the Lambrate district—is active; it groups together various associations in the area, including the SoSt, and organizes once a month the Saturday of Lambrate, with activities and initiatives to repopulate and revive the square. The SoSt has also participated in several Saturdays of Lambrate with the counter of used clothes, a very successful initiative and high level of participation.

The Group promotes the redevelopment of the public and private spaces of the area, from the historical districts, up to the former industrial zones that constitute a great heritage yet little appreciated not only by the Lambrate citizens, but also by the Milanese. ViviLambrate’s approach is to activate the human, creative and productive resources of the district and to promote citizen participation, in collaboration with the Municipality 3 and the support of the Institutions.

ViviLambrate is formed by 11 different organizations, which aggregates several thousand citizens of the area, yet also firms and private social actors active in different cultural, artistic and social fields, informal groups of citizens, start-ups, CSs, galleries of art and freelancers. From this network of experiences and the voluntary work of many citizens, the initiatives “There is life in the square! and “The Saturdays of Lambrate”, enlivens the streets of the neighbourhood every month, with particular attention to the elderly and children, and strong creative and supportive spirit.

These have undoubtedly generated interest and convinced architects and creative designers to settle even temporarily in the district using the existing coworking spaces. As mentioned beforehand, this is establishing a virtuous collaboration between coworkers, inhabitants and traders of the district that is progressively taking the area to a real urban regeneration “from below” (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Activities offered by the CSs. Source: Lisa Astolfi (co-author).

4. Conclusions

While places and modes of work are becoming increasingly collective and collaborative, citizens (residents and city users) increasingly express the need for new social spaces and places to recognize themselves: places to tame and make familiar. In the parts of the city in which these two phenomena occur simultaneously, spontaneous processes of shared urban regeneration, from below, can be triggered. This process, apparently longer and more tiring than a project with a top-down approach, offers higher guarantees of success over time as it directly involves all the social and economic forces (without discrimination) of the interested area in all of its phases of conception and realization.

Both the two phenomena of CSs and SoSts are served as important ‘third places’ [15]; the former being an alternative workplace and the latter a place for social gathering where broader, more creative interaction in a free non-privatized environment is encouraged. With the main aim to understand the interaction between these coworkers and streeters, the present paper has discussed the first outcomes of a research study on the relationship between new workplaces, such as CSs, and SoSts. As stated previously, in Milan 19 CSs out of 97 are located in areas of SoSts and this gives rise to initiatives located in the district (other than to their coworkers) of which the presented case of Lambrate-Milano-Social Street is just one example of a much wider phenomenon.

The paper has, therefore, put in evidence how the new workplaces, which emphasise the sense of community, can foster the development of collaboration with SoSts and subsequently contribute to the improvement of urban spaces and eventually urban regeneration. Therefore, tailored policies may be designed to foster the growth of CSs, especially considering depressed areas.

Author Contributions

All four authors have equally contributed to the design and implementation of the research. More specifically, the introduction, Section 2, Section 3.1 and Section 3.3 have been written by I.M. and M.A.; Section 3.2, Section 3.4 and Section 4 have been mostly developed and written by L.A. and A.C.

Funding

The project has been funded by FARB (2016) research project “New working spaces. Promises of innovations, effects on the economic and urban context” at Department of Architecture and Urban Studies (DAStU)—Politecnico di Milano, Coordinator: Ilaria Mariotti; Mina Akhavan was part of the research team.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Durante, G.; Turvani, M. Coworking, the Sharing Economy, and the City: Which Role for the “Coworking Entrepreneur”? Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinuzzi, C. Working Alone Together Coworking as Emergent Collaborative Activity. J. Bus. Tech. Commun. 2012, 26, 399–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriset, B. Building new places of the creative economy. The rise of coworking spaces. In Proceedings of the 2nd Geography of Innovation International Conference, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 23–25 January 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gandini, A. The Rise of Coworking Spaces: A Literature Review. Ephemer. Theory Politics Organ. 2015, 15, 193–205. [Google Scholar]

- Parrino, L. Coworking: Assessing the role of proximity in knowledge exchange. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2015, 13, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, I.; Akhavan, M. The Effects of Coworking Spaces on Local Communities in the Italian Context. Territorio 2018. accepted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Mariotti, I.; Akhavan, M. The Location of Coworking Spaces in Urban vs. Peripheral Areas. 2018. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Mariotti, I.; Pacchi, C.; Di Vita, S. Coworking Spaces in Milan: ICTs, Proximity, and Urban Effects. J. Urban Technol. 2017, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joroff, M.L. Workplace Mind Shifts. J. Corp. Real Estate 2002, 4, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Bhandarkar, A.; Rai, S. Millennials and the Workplace: Challenges for Architecting the Organizations of Tomorrow; Sage: New Delhi, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, T.D.; Veiga, J.F.; Dino, R.N. The impact of professional isolation on teleworker job performance and turnover intentions: Does time spent teleworking, interacting face-to-face, or having access to communication-enhancing technology matter? J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 1412–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.D.; Kurland, N.B. Telecommuting, professional isolation, and employee development in public and private organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 511–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriset, B.; Malecki, E.J. Organization versus space: The paradoxical geographies of the digital economy. Geogr. Compass 2009, 3, 256–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonner, K.L.; Stache, L.C. All in a day’s work, at home: Teleworkers’ management of micro role transitions and the work–home boundary. New Technol. Work Employ. 2012, 27, 242–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenburg, R. The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community; Da Capo Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1989; Available online: https://books.google.it/books?id=o4ZFCgAAQBAJ (accessed on 16 December 2018).

- Martins, J. The Extended Workplace in a Creative Cluster: Exploring Space(s) of Digital Work in Silicon Roundabout. J. Urban Des. 2015, 20, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marino, M.; Lapintie, K. Emerging Workplaces in Post-Functionalist Cities. J. Urban Technol. 2017, 24, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters-Lynch, J.; Potts, J.; Butcher, T.; Dodson, J.; Hurley, J. Coworking: A Transdisciplinary Overview. 2016. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2712217 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2712217 (accessed on 16 December 2018).

- Bilandzic, M. Connected learning in the library as a product of hacking, making, social diversity and messiness. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2016, 24, 158–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capdevila, I. Coworkers, Makers, and Fabbers Global, Local and Internal Dynamics of Innovation in Localized Communities in Barcelona. Ph.D. Thesis, HEC Montréal École affiliée à l‘Université de Montréal, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Capdevila, I. Different Entrepreneurial Approaches in Localized Spaces of Collaborative Innovation. 2014. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2533448 (accessed on 16 December 2018).

- Fuzi, A.; Clifton, N.; Loudon, G. New in-house organizational spaces that support creativity and innovation: The co-working space. In Proceedings of the R & D Management Conference, Stuttgart, Germany, 3–6 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Capdevila, I. Knowledge Dynamics in Localized Communities: Coworking Spaces as Microclusters. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2414121 (accessed on 9 December 2013).

- Davies, A.; Tollervey, K. The Style of Coworking: Contemporary Shared Workspaces; Prestel Verlag: Munich, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Merkel, J. Coworking in the city. Ephemer. Theory Politics Organ. 2015, 15, 121–139. [Google Scholar]

- Ibert, O. Relational distance: Sociocultural and time–spatial tensions in innovation practices. Environ. Plan. A 2010, 42, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, S.; Rodríguez-Baltanás, G.; Gallego, M.D. Coworking spaces: A new way of achieving productivity. J. Facil. Manag. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, A. Coworking spaces in mid-sized cities: A partner in downtown economic development. Environ. Plan. A 2018, 50, 773–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, J.; Glaeser, E.L. Information Technology and the Future of Cities. Urb. Econ. 1998, 43, 136–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualini, C. Vicini e Connessi. Rapporto Sulle Social Street a Milano; Fondazione Feltrinelli: Milan, Italia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Delpini, M. Per un’arte del buon Vicinato; Casa editrice ambrosiana: Milano, Italia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Boschma, R. Role of Proximity in Interaction and Performance: Conceptual and Empirical Challenges. Reg. Stud. 2005, 39, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, I.; Pacchi, C. Coworking spaces and urban effects in Italy. In Proceedings of the Urban Studies Foundation Seminar Series, EKKE, Athens, Greece, 8–9 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mariotti, I. The attractiveness of Milan and the spatial patterns of international firms. In Milan: Productions, Spatial Patterns and Urban Change; Armondi, S., Di Vita, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 48–59. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).