International Media and Tourism Industry as the Facilitators of Socialist Legacy Heritagization in the CEE Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Manipulation with Heritage and the Role of Media and Tourism

3. The Main Features of Urban Image and Identity (Re)construction in the CEE Region

4. Media and Tourism as Initiators of Heritage De-Contestation–Case Studies from Hungary, Romania, and the Former Yugoslavia

4.1. Tempering the Socialist Legacy in Budapest, Hungary

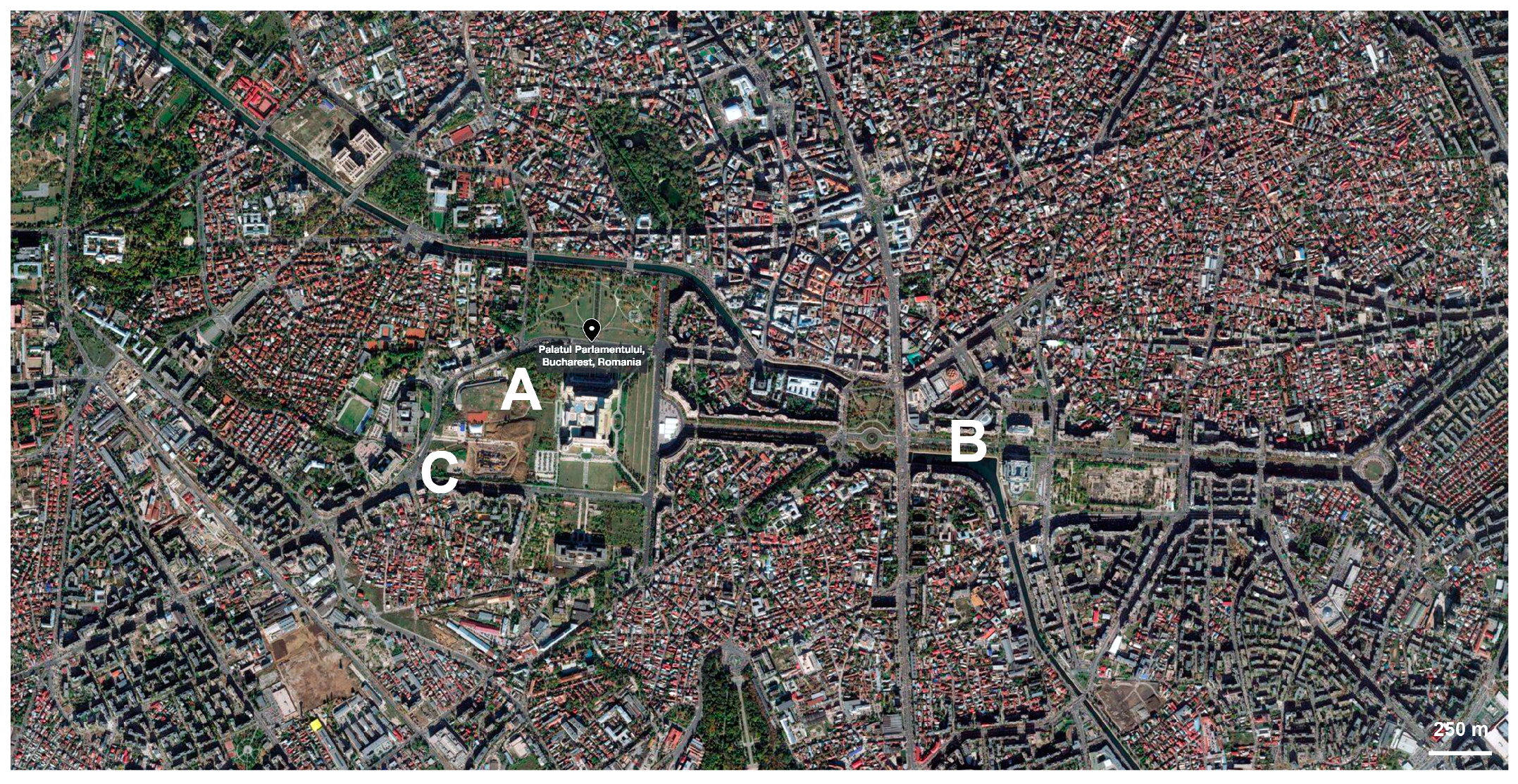

4.2. Compromising National Identity in Bucharest, Romania

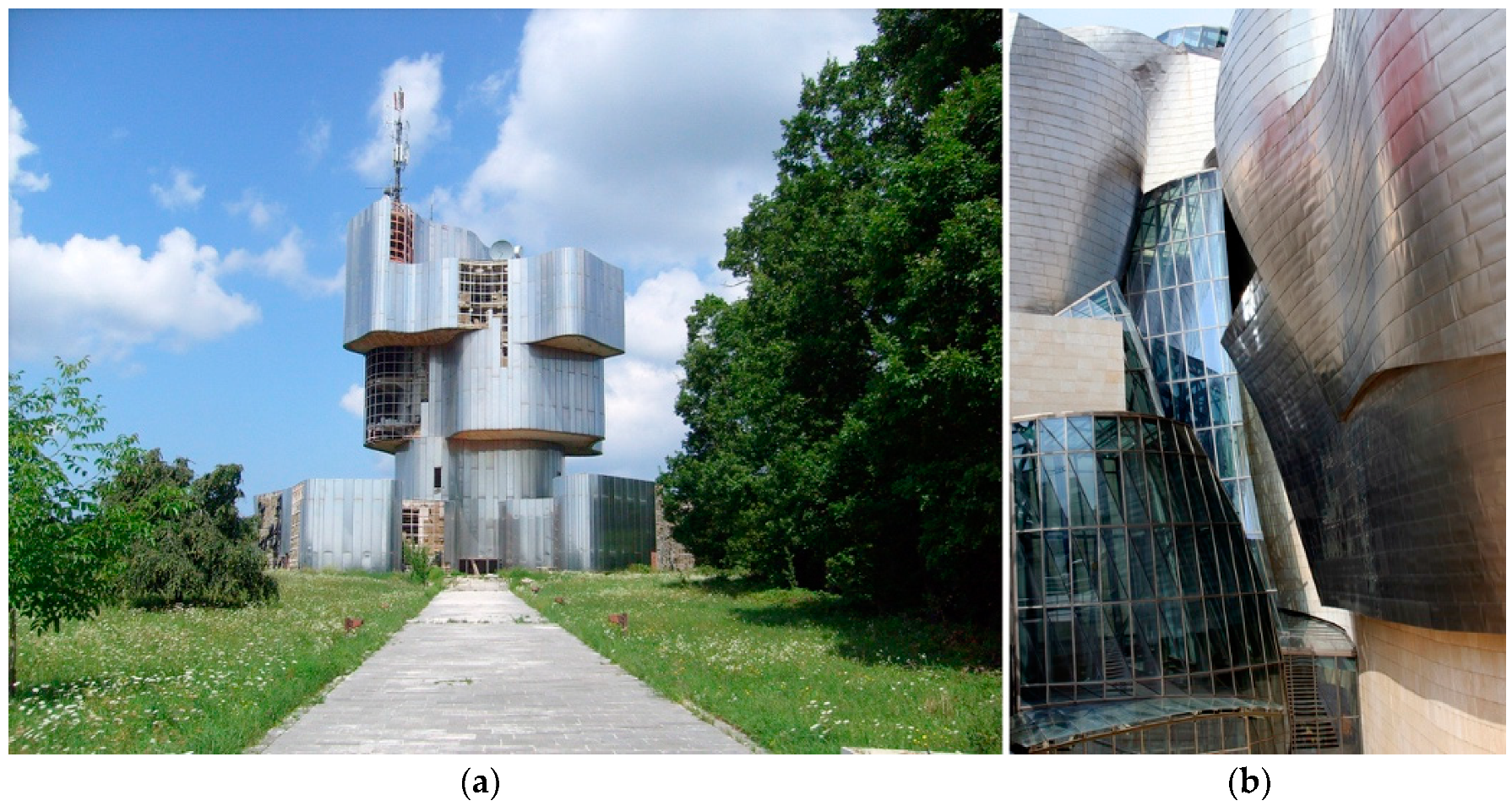

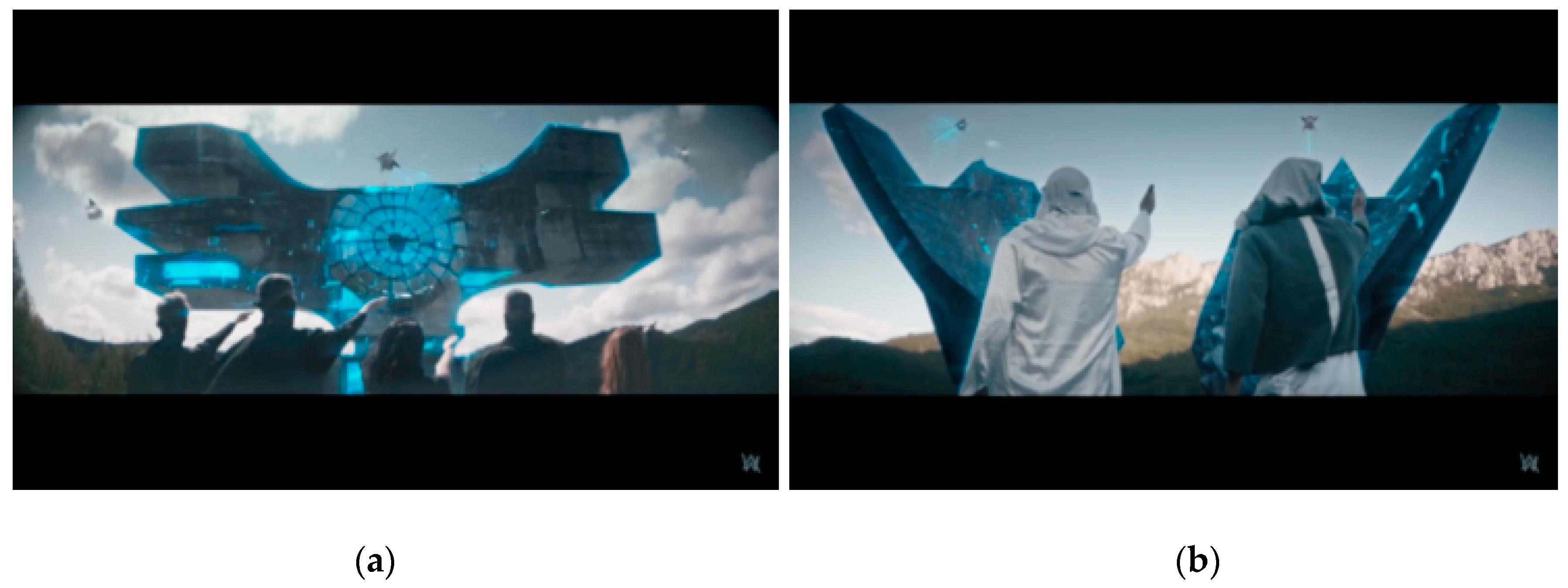

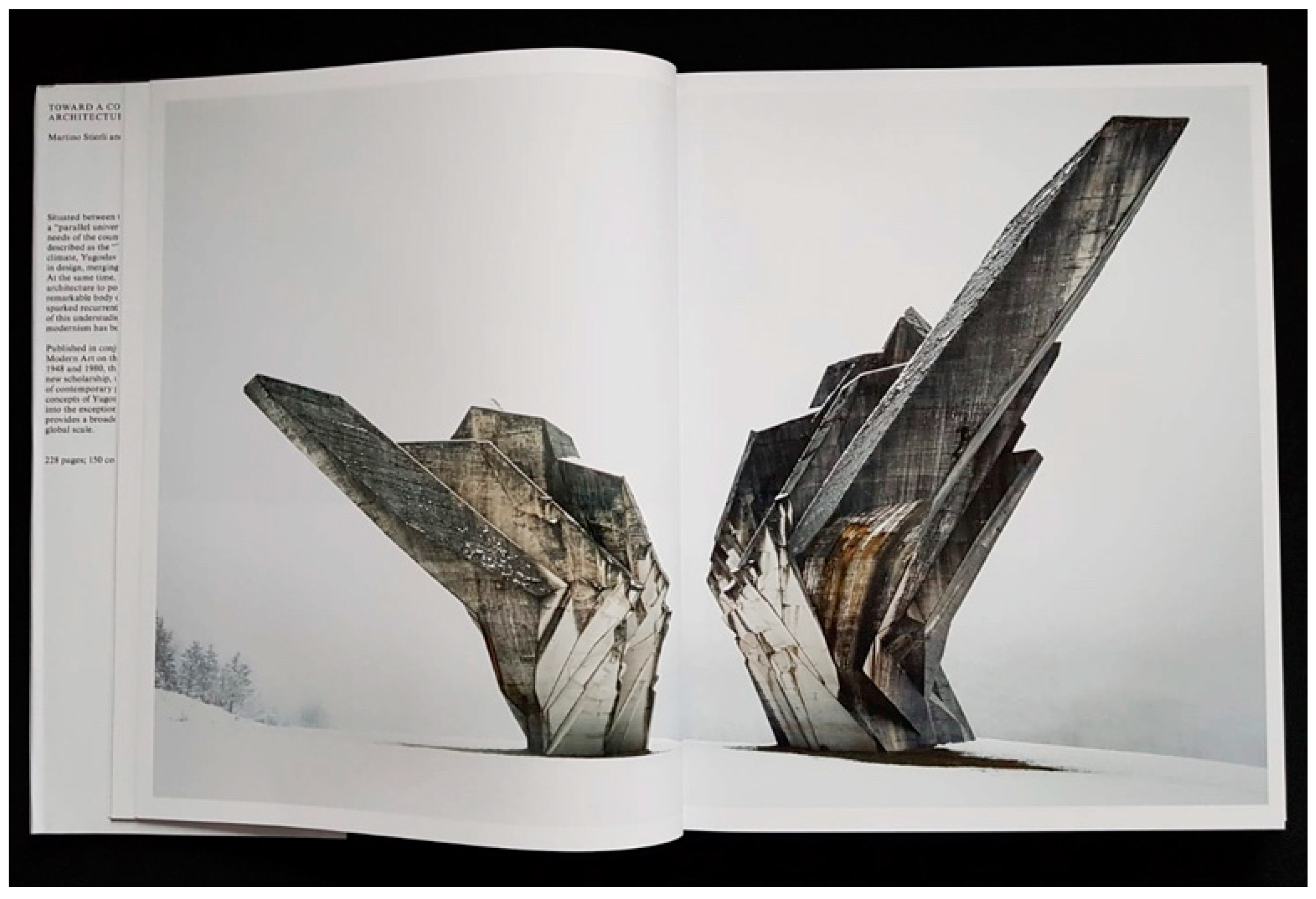

4.3. Changing Perspective on the Anti-Fascist Monuments of the Former Yugoslavia

5. Marketing Socialist Legacy—A Long Way from Repression towards Reconsideration

6. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Graham, B. (Ed.) Modern Europe-Place, Culture, Identity; Arnold: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gospodini, A. European cities and place-identity. Discuss. Pap. Ser. 2002, 8, 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth, G.J. The Conserved European City as Cultural Symbol: The Meaning of the Text. In Modern Europe. Place, Culture, Identity; Graham, B., Ed.; Arnold: London, UK, 1998; pp. 261–286. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, A.H. Conservation and Restoration in Built Heritage: A Western European Perspective. In The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity; Graham, B., Howard, P., Eds.; Ashgate: Farnham, UK; Burlington, VT, USA, 2008; pp. 245–265. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A. Die Architektur der Stadt–Skizze zu einer grundlegenden Theorie des Urbanen; Pennsylvania State University: State College, PA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Ebbe, K. Infrastructure and Heritage Conservation: Opportunities for Urban Revilatization and Economic Development; Directions in Urban Development; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rypkema, D.D. Heritage Conservation and the Local Economy. Glob. Urban Dev. Mag. 2008, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, B.W. Heritage Tourism: Conflicting Identities in the Modern World. In The Asgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity; Graham, B., Howard, P., Eds.; Ashgate: Farnham, UK; Burlington, VT, USA, 2008; pp. 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- Ulbricht, J.H.; Schröder-Esch, S. (Eds.) Introduction: The political dimension of heritage. In The Politics of Heritage and Regional Development Strategies—Actors, Interests, Conflicts; Bauhaus-Universität: Weimar, Germany, 2006; pp. 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Daugbjerg, M.; Fibiger, T. Introduction: Heritage Gone Global. Investigating the Production and Problematics of Globalized Pasts. Hist. Anthropol. 2011, 22, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organisation. UNWTO Annual Report 2017; World Tourism Organisation: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kulić, V. Orientalizing Socialism: Architecture, Media, and the Representations of Eastern Europe. Archit. Hist. 2018, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikonja, M. Lost in Transition? East Eur. Politics Soc. 2010, 23, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, M. The Inclusion of the Communist/Socialist Heritage in the Emerging Representations of Eastern Europe: The Case of Bulgaria. Tour. Cultue Commun. 2017, 17, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Draft Medium Term Plan (1990–1995), 25 C/4; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R. Forgetting to remember, remembering to forget: Late modern heritage practices, sustainability and the crisis of accumulation of the past. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2013, 19, 579–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, B.; Howard, P. (Eds.) Heritage and Identity. In The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity; Ashgate: Farnham, UK; Burlington, VT, USA, 2008; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, S. Heritage, Memory and Identity. In Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage Identity; Ashgate: Farnham, UK; Burlington, VT, USA, 2008; pp. 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher, M. Images of the past: Historical authenticity and inauthenticity from Disney to Times Square. CRM J. Herit. Steward. 2004, 1, 6–19. [Google Scholar]

- Soproni, L.; Horga, I. Global communication as a result of globalization and informatization. In Education, Research and Innovation. Policies and Strategies in the Age of Globalization; Bârgăoanu, A., Pricopie, R., Eds.; National School of Political Studies and Public Administration, Comunicare.ro: Bucureşti, Romania, 2008; pp. 267–273. [Google Scholar]

- Echtner, C.M.; Ritchie, J.R.B. The meaning and measurement of destination image. J. Tour. Stud. 1991, 2, 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, P. National identity building through patterns of an international third-person perception in news coverage. Int. Commun. Gaz. 2013, 75, 732–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; O’Connor, P. Information communication technology revolutionizing tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2005, 30, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanilov, K. (Ed.) The Post-Socialist City. Urban Form and Space Transformations in Central and Eastern Europe after Socialism; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sýkora, L. Post-Socialist Cities. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography; Kitchin, R., Thrift, N., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2009; Volume 8, pp. 387–395. [Google Scholar]

- McNeill, D.; Tewdwr-Jones, M. Architecture, banal nationalism and re-territorialization. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2003, 27, 738–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gospodini, A. Urban morphology and place identity in European cities: Built heritage and innovative design. J. Urban Des. 2004, 9, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, A.; Jonas, A. Reimagining Berlin: World City, National Capital or Ordinary Place? Eur. J. Reg. Stud. 1999, 6, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, D. Warsaw; Reaktion Books: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ágh, A. The Politics of Central Europe; SAGE: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Young, C.; Kaczmarek, S. The socialist past and postsocialist urban identity in Central and Eastern Europe: The case of Łódź, Poland. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2008, 15, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaszkiewicz, M.; Graburn, N.; Owsianowska, S. Tourism in (Post)socialist Eastern Europe. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2017, 15, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D. Gazing on communism: Heritage tourism and post-communist identities in Germany, Hungary and Romania. Tour. Geogr. 2000, 2, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hann, C. Transition, tradition, and nostalgia; postsocialist transformations in a comparative framework. Coll. Antropol. 2012, 36, 1119–1128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tunbridge, J.E. Whose heritage? Global problem, European Nightmare. In Building a New Heritage: Tourism, Culture and Identity in the New Europe; Ashworth, G.J., Larkham, P.J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1994; pp. 123–124. [Google Scholar]

- Haug, H.K. Creating a Socialist Yugoslavia: Tito, Communist Leadership and the National Question; IB Tauris: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jović, D. Communist Yugoslavia and Its Others; CEU Press: Budapest, Hungary, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- James, B. Fencing in the Past: Budapest’s Statue Park Museum. Media Cult. Soc. 1999, 21, 291–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalkó, G. Socail and geographical aspects of tourism in Budapest. Eur. Spat. Res. Policy 2001, 8, 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, J. Budapest’s Memento Park: Where communist statues are laid to rest. CNN Travel, 7 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lonely Planet, “Memento Park”. Available online: https://www.lonelyplanet.com/hungary/budapest/attractions/memento-park/a/poi-sig/412706/359522 (accessed on 21 August 2018).

- Budapest Festival and Tourism Center Nonprofit Ltd. BudapestInfo. Available online: https://www.budapestinfo.hu/top-sights (accessed on 8 October 2018).

- Light, D.; Young, C. Urban space, political identity and the unwanted legacies of state socialism: Bucharest’s problematic Centru Civic in the post-socialist era. Natl. Pap. 2013, 41, 515–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D. Street names in Bucharest, 1990–1997: Exploring the modern historical geographies of post-socialist change. J. Hist. Geogr. 2004, 30, 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D.; Young, C. Reconfiguring Socialist Urban Landscapes: The ‘Left-Over’ Spaces of State-Socialism in Bucharest. Hum. Geogr. 2010, 4, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Neacsu, M.C.; Negut, S.; Vlasceanu, G. The dynamic of foreign visitors in Romania since 1990. Current challenges of Romanian tourism. Amfiteatru Econ. 2014, 16, 1340–1351. [Google Scholar]

- Malathronas, J. See Nicolae Ceausescu’s grandiose and bloody legacy in Bucharest. CNN Travel. 2014. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/travel/article/ceausescu-trail-bucharest-romania/index.html (accessed on 8 October 2018).

- Euronews. Soviet Nostalgia? Take a Tour through Bucharest’s Communist Past! 2017. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/2017/03/22/soviet-nostalgia-take-a-tour-through-bucharest-s-communist-past (accessed on 8 October 2018).

- Unveil Romania. “The Ashes of Communism—Bucharest Private Tour”. Available online: http://unveilromania.com/romania-tours/bucharest-tours-communism/ (accessed on 26 October 2018).

- Begić, S.; Mraović, B. Forsaken Monuments and Social Change: The Function of Socialist Monuments in the Post- Yugoslav Space. In Symbols that Bind, Symbols that Divide; Moeschberger, S.L., DeZalia, R.A.P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 13–38. [Google Scholar]

- Gattin, M. Vjera u Ideal. In Novine Novine #12; Galerija Nova: Zagreb, Croatia, 2007; Volume 12, pp. 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Horvatinčić, S. Formalna heterogenost spomeničke skulpture i strategije sjećanja u socijalističkoj Jugoslaviji. Anal. Galerije Antuna Augustincica 2012, 31, 81–106. [Google Scholar]

- Jerković, D. Baština za muzeje ili skladišta otpada. Glas Slavonije, 26 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Surtees, J. Spomeniks: The second world war memorials that look like alien art. The Guardian, 19 June 2013; 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kempenaers, J. Spomenik; Roma Publication: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Paddison, R. City marketing. Image re-construction and urban regeneration. Urban Stud. 1993, 30, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S. Un-settling ‘the heritage’, re-imagining the post-nationWhose heritage? Third Text 1999, 13, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Čamprag, N. International Media and Tourism Industry as the Facilitators of Socialist Legacy Heritagization in the CEE Region. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci2040110

Čamprag N. International Media and Tourism Industry as the Facilitators of Socialist Legacy Heritagization in the CEE Region. Urban Science. 2018; 2(4):110. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci2040110

Chicago/Turabian StyleČamprag, Nebojša. 2018. "International Media and Tourism Industry as the Facilitators of Socialist Legacy Heritagization in the CEE Region" Urban Science 2, no. 4: 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci2040110

APA StyleČamprag, N. (2018). International Media and Tourism Industry as the Facilitators of Socialist Legacy Heritagization in the CEE Region. Urban Science, 2(4), 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci2040110