Energy Poverty in the Era of Climate Change: Divergent Pathways in Hungary and Jordan

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- to develop composite indicators that measure energy poverty, financial poverty, and climate perception–resilience within a climate-sensitive framework;

- (2)

- to empirically analyze the determinants of household energy poverty in two structurally similar but institutionally different regions in Hungary and Jordan; and

- (3)

- to derive policy-relevant insights for inclusive urban energy transitions, focusing on energy efficiency, resilience building, and social protection.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Energy Poverty

2.2. Financial Poverty

2.3. Theoretical Framework

3. Data and Methodology

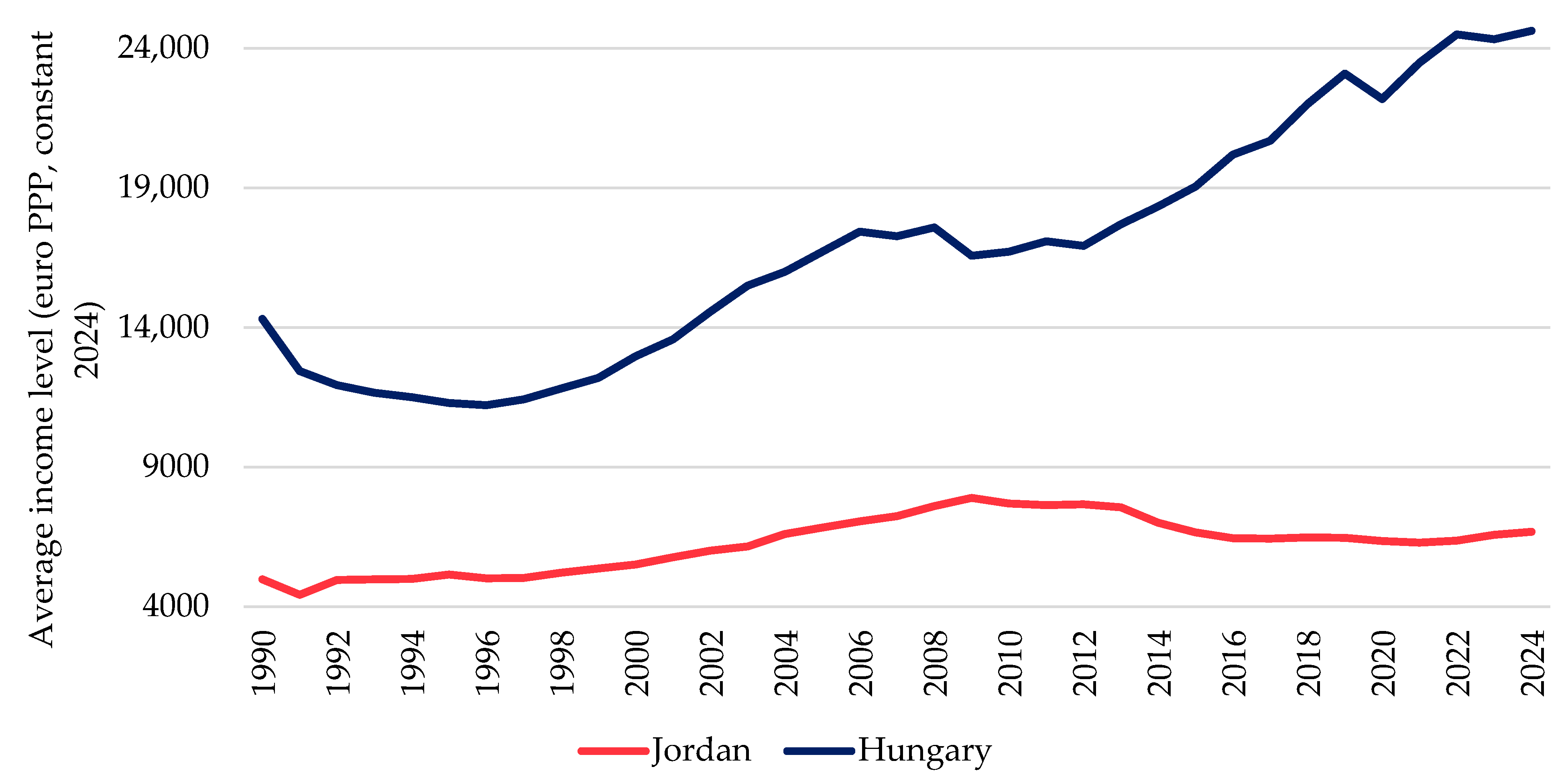

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Statistical Analysis

3.3.1. General Approach to Composite Construction

3.3.2. Composite Energy Poverty Indicator

3.3.3. Composite Financial Poverty Indicator

3.3.4. Composite Climate Change Perceptions and Resilience Indicator

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis of the Main Components

4.2. Multiple Linear Regression

4.3. Region-Specific Regression Analysis

4.3.1. Zarqa

4.3.2. Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén

5. Discussion

5.1. Financial Poverty as a Structural Driver of Energy Poverty

5.2. The Mitigating Role of Climate Resilience

5.3. Climate Perceptions as an Outcome of Lived Energy Hardship

5.4. Contextual Heterogeneity and the Limits of One-Size-Fits-All Policy

5.5. Policy Implications

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Study Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. IPCC Climate Change 2022—Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; ISBN 978-1-009-32584-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bouzarovski, S.; Petrova, S. A Global Perspective on Domestic Energy Deprivation: Overcoming the Energy Poverty–Fuel Poverty Binary. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 10, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaber, M.M. Multidimensional Energy Poverty in Jordan between 2009 and 2018: Progress and Possible Policy Interventions. Reg. Stat. 2023, 13, 434–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, J. Getting the Measure of Fuel Poverty, Final Report of the Fuel Poverty Review; Case Report 72; Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, London School of Economics and Political Science: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, C.C.; Gouveia, J.P. Chilling and Sweltering at Home: Surveying Energy Poverty and Thermal Vulnerability among Portuguese Higher Education Students. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2025, 119, 103842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaber, M.M. Summer Energy Poverty and Climate Change in Jordan; Veresné Somosi, M., Lipták, K., Harangozó, Z., Eds.; 2022; pp. 670–677. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/364317834_Summer_Energy_Poverty_And_Climate_Change_in_Jordan (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Thomson, H.; Simcock, N.; Bouzarovski, S.; Petrova, S. Energy Poverty and Indoor Cooling: An Overlooked Issue in Europe. Energy Build. 2019, 196, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaïd, F. Implications of Poorly Designed Climate Policy on Energy Poverty: Global Reflections on the Current Surge in Energy Prices. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 92, 102790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ürge-Vorsatz, D.; Cabeza, L.F.; Serrano, S.; Barreneche, C.; Petrichenko, K. Heating and Cooling Energy Trends and Drivers in Buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallegatte, S.; Bangalore, M.; Bonzanigo, L.; Kane, T.; Fay, M.; Narloch, U.; Treguer, D.; Rozenberg, J.; Vogt-Schilb, A. Shock Waves: Managing the Impacts of Climate Change on Poverty; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4648-0673-5. [Google Scholar]

- Csizmady, A.; Ferencz, Z.; Kőszeghy, L.; Tóth, G. Beyond the Energy Poor/Non Energy Poor Divide: Energy Vulnerability and Mindsets on Energy Generation Modes in Hungary. Energies 2021, 14, 6487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iammarino, S.; Rodriguez-Pose, A.; Storper, M. Regional Inequality in Europe: Evidence, Theory and Policy Implications. J. Econ. Geogr. 2019, 19, 273–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzarovski, S.; Tirado Herrero, S. Geographies of Injustice: The Socio-Spatial Determinants of Energy Poverty in Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary. Post-Communist Econ. 2017, 29, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Eguino, M. Energy Poverty: An Overview. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endrődi-Kovács, V.; Hegedüs, K. Energy Poverty in Hungary. Köz-Gazd.—Rev. Econ. Theory Policy 2019, 14, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Rumman, G.; Khdair, A.I.; Khdair, S.I. Current Status and Future Investment Potential in Renewable Energy in Jordan: An Overview. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzarovski, S. Energy Poverty in the European Union: Landscapes of Vulnerability. WIREs Energy Environ. 2014, 3, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPOV. Member State Report, Hungary; EU Energy Poverty Observatory: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- IEECP. Energy Renovation Roadmap—REER—Forstakeholders in the Somló-Marcalmente-Bakonyalja Region; IEECP: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jaber, M.M.; Stojilovska, A.; Yoon, H. Assessing the Determinants of Energy Poverty in Jordan Based on a Novel Composite Index. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menyhert, B. Energy Poverty—New Insights for Measurement and Policy; European Commission: Ispra, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. World Bank Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2022: Correcting Course; Poverty and Shared Prosperity; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-1-4648-1893-6. [Google Scholar]

- Alkire, S.; Foster, J. Counting and Multidimensional Poverty Measurement. J. Public Econ. 2011, 95, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravallion, M. The Economics of Poverty: History, Measurement, and Policy; Oxford Scholarship Online Economics and Finance; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-0-19-021280-3. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Income Inequality and Poverty. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/income-inequality.html (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Siposne Nandori, E. Individualism or Structuralism–Differences in the Public Perception of Poverty between the United States and East-Central Europe. J. Poverty 2022, 26, 337–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siposné Nándori, E.; Roufs, T.G. The Effect of Economic Conditions on Poverty Perception in Minnesota. SN Soc. Sci. 2023, 3, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaton, A.; Zaidi, S. Guidelines for Constructing Consumption Aggregates for Welfare Analysis; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-307-87429-0. [Google Scholar]

- Dercon, S. Growth and Shocks: Evidence from Rural Ethiopia. J. Dev. Econ. 2004, 74, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M. The Health Gap: The Challenge of an Unequal World. Lancet 2015, 386, 2442–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Duflo, E. Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty, 1st ed.; Public Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-58648-798-0. [Google Scholar]

- Mani, A.; Mullainathan, S.; Shafir, E.; Zhao, J. Poverty Impedes Cognitive Function. Science 2013, 341, 976–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, R.G.; Pickett, K. The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better; Allen Lane: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-1-84614-039-6. [Google Scholar]

- Fiszbein, A.; Schady, N.R.; Ferreira, F.H.G.; Grosh, M.E.; Keleher, N.; Olinto, P.; Skoufias, E. Conditional Cash Transfers: Reducing Present and Future Poverty; World Bank Policy Research Report; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-8213-7352-1. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J.E. The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future, 1st ed.; W. W. Norton & Company, Incorporated: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-393-34506-3. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat Risk of Poverty or Social Exclusion in 2024. Format Res. 2025. Available online: https://formatresearch.com/en/2025/04/30/risk-of-poverty-or-social-exclusion-in-2024-eurostat/ (accessed on 12 January 2026).

- Trading Economics Hungary—At Risk of Poverty Rate 2024. Available online: https://tradingeconomics.com/hungary/at-risk-of-poverty-rate-eurostat-data.html (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Jordan News More than One-Third of Jordanians Live below Poverty Line, Report Finds. Jordan News. 12 July 2023. Available online: https://www.jordannews.jo/Section-109/News/More-than-one-third-of-Jordanians-live-below-poverty-line-report-finds-29697 (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- World Bank. World Bank Atlas of Sustainable Development Goals 2023; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (Ed.) 2023 Country Report Hungary; European Economy Institutional Paper; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023; ISBN 978-92-68-03208-4. [Google Scholar]

- Belaïd, F.; Al-Sarihi, A.; Al-Mestneer, R. Balancing Climate Mitigation and Energy Security Goals amid Converging Global Energy Crises: The Role of Green Investments. Renew. Energy 2023, 205, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhou, J.; Liang, Y.; Yu, H.; Jing, R. Climate Change Impacts on City-Scale Building Energy Performance Based on GIS-Informed Urban Building Energy Modelling. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 125, 106331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piggot-Navarrete, J.; Blanchet, P.; Cabral, M.R.; Cogulet, A. Impact of Climate Change on the Energy Demand of Buildings Utilizing Wooden Prefabricated Envelopes in Cold Weather. Energy Build. 2025, 338, 115714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Gao, X.; Xu, Y.; Giorgi, F.; Chen, D. Effects of Climate Change on Heating and Cooling Degree Days and Potential Energy Demand in the Household Sector of China. Clim. Res. 2016, 67, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgili, F.; Kuskaya, S.; Magazzino, C.; Khan, K.; Hoque, M.E.; Alnour, M.; Onderol, S. The Mutual Effects of Residential Energy Demand and Climate Change in the United States: A Wavelet Analysis. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2024, 22, 100384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessel, S.; Sawyer, S.; Hernández, D. Energy, Poverty, and Health in Climate Change: A Comprehensive Review of an Emerging Literature. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Song, H.; Duan, M.; Zhu, Y.; Luo, X. Impact of Energy Affordability on the Decision-Making of Rural Households in Ecologically Fragile Areas of Northwest China Regarding Clean Energy Use. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2023, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, I.; Gouveia, J.P. Growing up in Discomfort: Exploring Energy Poverty and Thermal Comfort among Students in Portugal. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 113, 103550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Valkengoed, A.M.; Perlaviciute, G.; Steg, L. Relationships between Climate Change Perceptions and Climate Adaptation Actions: Policy Support, Information Seeking, and Behaviour. Clim. Change 2022, 171, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antronico, L.; Carone, M.T.; Coscarelli, R. An Approach to Measure Resilience of Communities to Climate Change: A Case Study in Calabria (Southern Italy). Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2023, 28, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD; European Union. Joint Research Centre—European Commission Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide; OECD: Paris, France, 2008; ISBN 978-92-64-04345-9. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-5264-1952-1. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman, B. Fuel Poverty: From Cold Homes to Affordable Warmth; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1991; ISBN 978-1-85293-139-1. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, H.; Snell, C.; Liddell, C. Fuel Poverty in the European Union: A Concept in Need of Definition? People Place Policy 2016, 10, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, S.T. Energy Poverty Indicators: A Critical Review of Methods. Indoor Built Environ. 2017, 26, 1018–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middlemiss, L.; Gillard, R. Fuel Poverty from the Bottom-up: Characterising Household Energy Vulnerability through the Lived Experience of the Fuel Poor. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.; Day, R. Fuel Poverty as Injustice: Integrating Distribution, Recognition and Procedure in the Struggle for Affordable Warmth. Energy Policy 2012, 49, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzarovski, S.; Petrova, S.; Tirado-Herrero, S. From Fuel Poverty to Energy Vulnerability: The Importance of Services, Needs and Practices. 2014. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273898762_From_Fuel_Poverty_to_Energy_Vulnerability_The_Importance_of_Services_Needs_and_Practices (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Wolf, J.; Adger, W.N.; Lorenzoni, I.; Abrahamson, V.; Raine, R. Social Capital, Individual Responses to Heat Waves and Climate Change Adaptation: An Empirical Study of Two UK Cities. Glob. Environ. Change 2010, 20, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén (n = 221) | Zarqa (n = 218) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 29.0% | 31.7% |

| Female | 71.0% | 68.3% | |

| Area | Urban | 57.0% | 82.1% |

| Rural | 43.0% | 17.9% | |

| Education | None | 0.50% | 0.00% |

| Primary education | 1.40% | 6.40% | |

| Secondary education | 34.4% | 24.8% | |

| Tertiary education | 63.8% | 68.8% | |

| Employment status | Full time | 70.1% | 21.1% |

| Part-time | 4.10% | 7.30% | |

| Contract or temporary | 0.50% | 3.20% | |

| Public employment | 3.20% | 12.4% | |

| Retired | 7.20% | 8.70% | |

| Unemployed | 2.30% | 22.5% | |

| Dependent | 3.60% | 3.20% | |

| Self-employed | 3.20% | 5.00% | |

| Other | 5.90% | 16.5% |

| County | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zarqa | EP | 0.000 | 9.000 | 2.620 | 2.143 |

| FP | 1.000 | 4.800 | 2.186 | 0.619 | |

| CP | 1.000 | 5.000 | 4.002 | 0.712 | |

| CR | 1.000 | 5.000 | 3.519 | 0.728 | |

| Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén | EP | 0.000 | 9.000 | 5.450 | 2.695 |

| FP | 1.000 | 5.000 | 3.190 | 0.993 | |

| CP | 1.400 | 5.000 | 3.911 | 0.597 | |

| CR | 2.000 | 5.000 | 3.593 | 0.627 | |

| Predictor | B | SE (B) | β | t | p | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | 1.183 | 0.822 | — | 1.439 | 0.151 | — |

| CP | 0.358 | 0.170 | +0.084 | 2.109 | 0.036 | 1.140 |

| CR | −0.661 | 0.168 | −0.160 | −3.931 | <0.001 | 1.189 |

| FP | 1.065 | 0.131 | +0.366 | 8.147 | <0.001 | 1.453 |

| Region (1 = Borsod, 0 = Zarqa) | 1.842 | 0.251 | +0.328 | 7.354 | <0.001 | 1.433 |

| Predictor | Zarqa (B) | Zarqa (SE) | Zarqa (β) | p | Borsod (B) | Borsod (SE) | Borsod (β) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | −0.709 | 0.205 | −0.241 | 0.001 | −0.544 | 0.280 | −0.127 | 0.053 |

| CP | 0.244 | 0.207 | 0.081 | 0.240 | 0.684 | 0.290 | 0.152 | 0.019 |

| FP | 0.456 | 0.270 | 0.132 | 0.093 | 1.260 | 0.220 | 0.464 | <0.001 |

| Household net monthly income | −0.184 | 0.108 | −0.137 | 0.090 | 0.018 | 0.103 | 0.015 | 0.859 |

| Gender | 0.448 | 0.295 | 0.095 | 0.131 | −0.116 | 0.352 | −0.020 | 0.743 |

| Age | −0.022 | 0.010 | −0.141 | 0.028 | 0.006 | 0.015 | 0.024 | 0.706 |

| Educational level | −0.505 | 0.282 | −0.127 | 0.075 | 0.219 | 0.308 | 0.049 | 0.478 |

| Constant | 6.209 | 1.463 | — | <0.001 | −0.109 | 1.844 | — | 0.953 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jaber, M.M.; Siposné Nándori, E.; Lipták, K. Energy Poverty in the Era of Climate Change: Divergent Pathways in Hungary and Jordan. Urban Sci. 2026, 10, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10020075

Jaber MM, Siposné Nándori E, Lipták K. Energy Poverty in the Era of Climate Change: Divergent Pathways in Hungary and Jordan. Urban Science. 2026; 10(2):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10020075

Chicago/Turabian StyleJaber, Mohammad M., Eszter Siposné Nándori, and Katalin Lipták. 2026. "Energy Poverty in the Era of Climate Change: Divergent Pathways in Hungary and Jordan" Urban Science 10, no. 2: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10020075

APA StyleJaber, M. M., Siposné Nándori, E., & Lipták, K. (2026). Energy Poverty in the Era of Climate Change: Divergent Pathways in Hungary and Jordan. Urban Science, 10(2), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10020075