Improving the Level of Responsibility Classification for Pedestrian Crashes with the Multilayer Perceptron Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

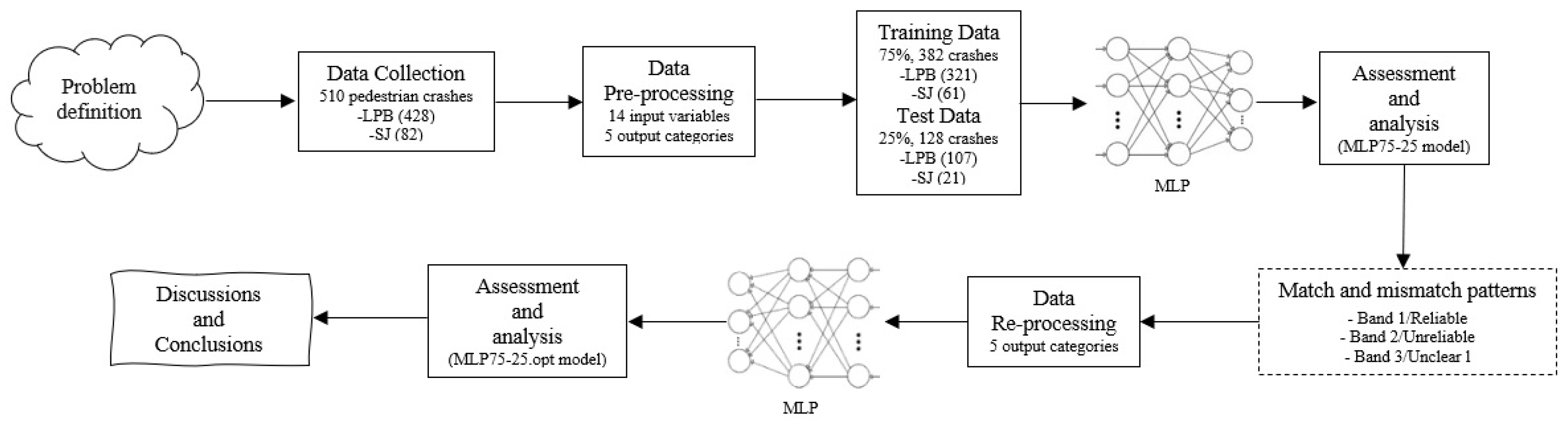

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Project Summary

2.2. Data

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. The MLP Neural Network Model

2.3.2. Performance Metrics

2.4. Model Structure

2.4.1. Neural Network Structure

2.4.2. Classification Process

3. Results

| Model | ACC | |

|---|---|---|

| Train | Validation | |

| MLP75-25 | 0.8538 | 0.7266 |

| MLP75-25.opt | 0.9084 | 0.8906 |

| Category | ACC | R | P | S | F1S | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLP 75-25 | MLP 75-25.opt | MLP 75-25 | MLP 75-25.opt | MLP 75-25 | MLP 75-25.opt | MLP 75-25 | MLP 75-25.opt | MLP 75-25 | MLP 75-25.opt | |

| A | 0.8672 | 0.9844 | 0.8817 | 0.9880 | 0.9318 | 0.9880 | 0.8286 | 0.9778 | 0.9061 | 0.9880 |

| B | 0.8750 | 0.9375 | 0.7500 | 0.7857 | 0.3000 | 0.6875 | 0.8833 | 0.9561 | 0.4286 | 0.7333 |

| C | 0.8828 | 0.9688 | 0.1538 | 0.7286 | 0.3333 | 1.0000 | 0.9652 | 1.0000 | 0.2105 | 0.6000 |

| D | 0.9219 | 0.9297 | 0.1429 | 0.7857 | 0.2000 | 0.6471 | 0.9669 | 0.9474 | 0.1667 | 0.7097 |

| E | 0.9062 | 0.9609 | 0.2857 | 0.7000 | 0.2222 | 0.7778 | 0.9421 | 0.9831 | 0.2500 | 0.7368 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| JTP | Judicial Traffic Police |

| LPB | Local Police of Badajoz |

| SJ | Spanish Judiciary |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| LM | Levenberg–Marquardt |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| AUC | Area Under Curve |

| ACC | Accuracy |

| R | Recall |

| P | Precision |

| S | Specificity |

| F1S | F1Score |

| MF1S | Macro F1Score |

| BACC | Balanced Accuracy |

| κ | Cohen’s kappa coefficient |

References

- Shaik, E.; Islam, M.; Quazi Sazzad, H. A review on neural network techniques for the prediction of road traffic accident severity. Asian Transp. Stud. 2021, 7, 100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameen, M.I.; Pradhan, B. Assessment of the effects of expressway geometric design features on the frequency of accident crash rates using high-resolution laser scanning data and GIS. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2016, 8, 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado-Sanz, N.; Guirao, B.; Galera, A.L.; Attard, M. Investigating the Risk Factors Associated with the Severity of the Pedestrians Injured on Spanish Crosstown Roads. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Road Safety Observatory. Annual Statistical Report on Road Safety in the EU 2022; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://transport.ec.europa.eu/background/road-safety-statistics-2023_en (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Status Report on Road Safety 2023; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health/safety-and-mobility/global-status-report-on-road-safety-2023?utm_source=copilot.com (accessed on 3 January 2026).

- United Stated Department of Transportation. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Available online: https://crashstats.nhtsa.dot.gov/ (accessed on 3 January 2026).

- European Road Safety Observatory. Annual Accident Report. Available online: https://road-safety.transport.ec.europa.eu/european-road-safety-observatory/statistics-and-analysis-archive/annual-accident-report_en (accessed on 3 January 2026).

- Asian Transport Observatory. ATO National Database Masterlist of Indicators. Available online: https://asiantransportobservatory.org/snd-masterlist/?indicator=INF-CFP-001 (accessed on 3 January 2026).

- Fian, T.; Hauger, G. Identifying High-Risk Patterns in Single-Vehicle, Single-Occupant Road Traffic Accidents: A Novel Pattern Recognition Approach. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulhafedh, A. Road Crash Prediction Models: Different Statistical Modeling Approaches. J. Transport. Technol. 2017, 7, 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, B.G.; De Bumbacher, A.; Deublein, M.; Adey, B.T. Predicting road traffic accidents using artificial neural network models. Infrastruct. Asset Manag. 2018, 5, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Mukherjee, D.; Mitra, S. Development of pedestrian crash prediction model for a developing country using artificial neural network. Int. J. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 2019, 26, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iljoon, C.; Park, H.; Hong, E.; Jaeduk, L.; Kwon, N. Predicting effects of built environment on fatal pedestrian accidents at location-specific level: Application of XGBoost and SHAP. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2022, 166, 106545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dongyu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Qiaojun, X. Geographically weighted random forests for macro-level crash frequency prediction. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 194, 107370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subasish, D.; Tamakloe, R.; Zubaidi, H.; Obaid, I.; Alnedawi, A. Fatal pedestrian crashes at intersections: Trend mining using association rules. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 160, 106306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, A.; Mazharul, H.; Mannering, F. A Bayesian generalised extreme value model to estimate real-time pedestrian crash risks at signalised intersections using artificial intelligence-based video analytics. Anal. Methods Accid. Res. 2023, 38, 100264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, A.; Guler, S.I.; Gayah, V.V.; Warchol, S. Evaluating the reliability of automatically generated pedestrian and bicycle crash surrogates. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 203, 107614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaysir, A.; Sherrie-Anne, K.; Schroeter, R.; Mazharul, H. A game theoretical model to examine pedestrian behaviour and safety on unsignalised slip lanes using AI-based video analytics. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2025, 217, 108034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qingwen, P.; Kun, X.; Hongyu, G.; Yuan, Z. Modeling crash avoidance behaviors in vehicle-pedestrian near-miss scenarios: Curvilinear time-to-collision and Mamba-driven deep reinforcement learning. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2025, 214, 107984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Li, J. Pedestrian Trajectory Prediction Based on Dual Social Graph Attention Network. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, D.; Shim, J. The Association Between Aggressive Driving Behaviors and Elderly Pedestrian Traffic Accidents: The Application of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI). Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; He, H. An Artificial-Intelligence-Based Semantic Assist Framework for Judicial Trials. Asian J. Law Soc. 2020, 7, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataleta, M.S. Humane Artificial Intelligence: The Fragility of Human Rights Facing AI; East-West Center: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh, C. Artificial Intelligence. In New Tech, New Threats, and New Governance Challenges: An Opportunity to Craft Smarter Responses? Carnegie Endowment for International Peace: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Jongbloed, A.W.; Nakad-Westrate, H.J.; Herik, H.; Salem, A.M. The rise of the robotic judge in modern court proceedings. In Proceedings of the ICIT 2015 The 7th International Conference on Information Technology, Amman, Jordan, 12–15 May 2015; pp. 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N. Black box justice: Robot judges and AI-based judgment processes in China’s court system. In 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Technology and Society (ISTAS); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelazm, K.S.; Dganni, K.M.; Tawakol, F.; Sharif, H. Robotic Judges: A New Step Towards Justice or the Exclusion of Humans? J. Lifestyle SDGs Rev. 2024, 4, e02515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, L. Data Protection and e Privacy: From Spam and Cookies to Big Data, Machine Learning and Profiling. In Law, Policy and the Internet; Lilian, E., Ed.; Hart Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 119–164. [Google Scholar]

- Barysė, D.; Sarel, R. Algorithms in the court: Does it matter which part of the judicial decision-making is automated? Art. Intellig. Law 2023, 32, 117–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matić-Bošković, M. Impact of artificial intelligence on practicing judicial professions. Sociol. Pregl. 2024, 58, 481–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinadaily. China Uses AI Assistive Tech on Court Trial for First Time. Available online: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201901/24/WS5c4959f9a3106c65c34e64ea.html (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- El Confidencial. Maite.ai: La IA capaz de Dictar Sentencias Revoluciona los Despachos de Abogados. Available online: https://www.elconfidencial.com/espana/cataluna/2025-04-19/inteligencia-artificial-juridico-maite-1hms_4108936 (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Sourdin, T. Judge v Robot? Artificial intelligence and judicial decision-making. Univ. N. S. W. Law J. 2018, 41, 1114–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulenaers, J. The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on the Right to a Fair Trial: Towards a Robot Judge? Asian J. Law Econom. 2020, 11, 20200008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chronowski, N.; Kálmán, K.; Szentgáli-Tóth, B. Artificial Intelligence, Justice, and Certain Aspects of Right to a Fair Trial. Acta Univer. Sapient. Leg. Stud. 2021, 10, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watamura, E.; Liu, Y.; Ioku, T. Judges versus artificial intelligence in juror decision-making in criminal trials: Evidence from two pre-registered experiments. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0318486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, A.; Berthelot, E.R.; Marsh, S. Public Perceptions of Judges’ Use of AI Tools in Courtroom Decision-Making: An Examination of Legitimacy, Fairness, Trust, and Procedural Justice. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xue, Q.; Guo, W.; Tan, J. Enhancing Model Transparency: A Comparative Analysis of SHAP and LIME in Explaining Traffic Accident Prediction Models. In The Proceedings of 2024 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Autonomous Transportation (AIAT 2024); Jia, L., Yao, D., Ma, F., Zhang, L., Chen, Y., Xue, Q., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; Volume 1391, pp. 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Alanazi, F.; Umar, I.K.; Yosri, A.M.; Okail, M.A. Comparative evaluation of deep learning and traditional models for predicting traffic accident severity in Saudi Arabia. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 32568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicent, J.F.; Curado, M.; Oliver, J.L.; Pérez-Sala, L. A novel approach to predict the traffic accident assistance based on deep learning. Neural Comput. Applic. 2025, 37, 5343–5368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahador Parsa, A.; Movahedi, A.; Taghipour, H.; Derrible, S.; Mohammadian, A. Toward safer highways, application of XGBoost and SHAP for real-time accident detection and feature analysis. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 136, 105405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, D. Decision Support Systems: Concepts and Resources for Managers; Greenwood Publishing Group: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Volokh, E. Chief Justice Robots. Duke Law J. 2019, 68, 1134–1192. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, F.Y.; Liu, Y.D.; Gao, F.; Wang, K. Research on constructing an artificial intelligence judicial database based on graph fusion. J. Yangzhou Univ. 2019, 23, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, I. Toward a Theory of Justice for Artificial Intelligence. Daedalus 2022, 151, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campón Domínguez, J.A. El Diseño de Una Base de Datos de Investigaciones en Profundidad Sobre Atropellos a Peatones. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Carlos III, Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Sanfélix, A.; Gragera-Peña, F.C.; Jaramillo-Morán, M.A. An improvement of the conceptual system of the sequential events model of road crashes (i-MOSES). Heliyon 2024, 10, e37268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haykin, S. Neural Networks. A Comprehensive Foundation, 2nd ed.; Pentince-Hall: Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rather, A.M.; Agarwal, A.; Sastry, V.N. Recurrent neural network and a hybrid model for prediction of stock returns. Expert. Syst. Applicat. 2015, 42, 3234–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göçken, M.; Özçalıcı, M.; Boru, A.; Dosdogru, A.T. Integrating metaheuristics and Artificial Neural Networks for improved stock price prediction. Expert. Syst. Applicat. 2016, 44, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, C.; Ploae, C.; Melnic, L.V.; Cotrumba, M.; Gurau, A.; Alexandra, C. Sustainability through the use of modern simulation methods applied artificial intelligence. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornik, K.; Stinchcombe, M.; White, H. Multilayer Feedforward Networks Are Universal Approximators. Neural Netw. 1989, 2, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cybenko, G. Approximation by Superpositions of a Sigmoidal Function. Math. Control Signals Syst. 1989, 2, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zeng, L.; Cao, K.; Wang, M.; Peng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, W. All Spin Artificial Neural Networks Based on Compound Spintronic Synapse and Neuron. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circ. Syst. 2016, 10, 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, M.W.; Dorling, S.R. Artificial neural networks (the multilayer perceptron)—A review of applications in the atmospheric sciences. Atm. Environ. 1998, 32, 2627–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.; Chong, D.; Batarseh, F.A. Foundations of data imbalance and solutions for a data democracy. In Data Democracy; Batarseh, F.A., Yang, R., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shung, K.P. Accuracy, Precision, Recall, or F1? 2018. Available online: https://medium.com/data-science/accuracy-precision-recall-or-f1-331fb37c5cb9 (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Yang, Y.; Liu, X. A re-examination of text categorization methods. In Proceedings of the SIGIR ‘99: Proceedings of the 22nd Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Berkeley, CA, USA, 1 August 1999; pp. 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Brodersen, K.H.; Ong, C.S.; Stephan, K.E.; Buhmann, J.M. The Balanced Accuracy and Its Posterior Distribution. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Istanbul, Turkey, 7 October 2010; pp. 3121–3124. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ. Psychol. Measurem. 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeremiah, R.; Way, P.D.; Firat, C.; Thanh-Nam, D.; Sartipi, M. Modeling and predicting vehicle accident occurrence in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 149, 105860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhai, H.; Cao, X.; Geng, X. Cause Analysis and Accident Classification of Road Traffic Accidents Based on Complex Networks. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ibiza, D. Situación “caótica” en la Unidad de Atestados de la Guardia Civil de Tráfico de Ibiza: Esta Semana se Queda Bajo Mínimos. Available online: https://www.diariodeibiza.es/ibiza/2024/02/19/situacion-caotica-unidad-atestados-guardia-98371856.html (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Asociación Unificada de Guardias Civiles. AUGC Denuncia la Precariedad Laboral de los Equipos de Atestados de Tráfico en la Provincia de Badajoz. Available online: https://www.augc.org/actualidad/augc-denuncia-precariedad-laboral-equipos-atestados-trafico-en-provincia-badajoz_21957_102.html (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Noticias de Navarra. Denuncian Falta de Personal y Formación en la Brigada de Atestados de Policía Foral. Available online: https://www.noticiasdenavarra.com/sucesos/2024/06/20/denuncian-falta-personal-formacion-brigada-8379901.html (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- del Río Montesdeoca, L. Necesidad De Una Fiscalía Especializada En Seguridad Vial. Logos Guard. Civil 2024, 29, 13–50. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, C.; Viallon, V.; Bouaoun, L.; Martin, J.-L. Prediction of responsibility for drivers and riders involved in injury road crashes. J. Saf. Res. 2019, 70, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yihong, L.; Yunpeng, W.; Tao, L.; Beibei, L.; Xiaolong, L. SP-SMOTE: A novel space partitioning based synthetic minority over-sampling technique. Knowl. Based Syst. 2021, 228, 107269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Sharma, R.; Dhaliwal, M.K. Evaluating Performance of SMOTE and ADASYN to Classify Falls and Activities of Daily Living. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Soft Computing for Problem Solving. (SocProS 2023); Pant, M., Deep, K., Nagar, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; Volume 995, pp. 315–324. [Google Scholar]

- Suja, A.A. Imbalanced data learning using SMOTE and deep learning architecture with optimized features. Neural Comput. Applic. 2025, 37, 967–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Region | Crash Rate (Deaths per 100,000 Inhabitants) | Social Costs | Pedestrian Fatality Trends |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | U.S. | 12.4 | 240,000 M$ | Slight increase (3%) |

| Europe | 5.0 | 100,000 M€ | Balanced | |

| Asia | 20.0 | 400,000 M$ | Increase (5–7%) | |

| 2019 | U.S. | 13.0 | 245,000 M$ | Slight decrease (1–2%) |

| Europe | 4.8 | 105,000 M€ | Slight decrease (2%) | |

| Asia | 18.5 | 420,000 M$ | Balanced | |

| 2020 | U.S. | 12.5 | 230,000 M$ | Balanced |

| Europe | 4.7 | 110,000 M€ | Balanced | |

| Asia | 19.0 | 430,000 M$ | Increase (6%) | |

| 2021 | U.S. | 14.0 | 260,000 M$ | Increase (6–7%) |

| Europe | 4.5 | 115,000 M€ | Balanced | |

| Asia | 18.0 | 440,000 M$ | Increase (4%) | |

| 2022 | U.S. | 14.3 | 265,000 M$ | Increase (5%) |

| Europe | 4.4 | 120,000 M€ | Slight decrease (1%) | |

| Asia | 17.5 | 450,000 M$ | Increase (3%) | |

| 2023 | U.S. | 13.9 | 270,000 M$ | Balanced |

| Europe | 4.3 | 125,000 M€ | Balanced | |

| Asia | 16.5 | 460,000 M$ | Balanced | |

| 2024 | U.S. | 12.8 | 280,000 M$ | Slight decrease (1–2%) |

| Europe | 4.2 | 130,000 M€ | Slight decrease (1%) | |

| Asia | 16.0 | 470,000 M$ | Balanced |

| Subsystem | Num | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human | H-1 | PPP and RPP match. The driver is attentive while driving | 1 |

| PPP and RPP do not match. The driver is inattentive while driving | 0 | ||

| H-2 | RT ≤ 0.75 s (average of a normal person) | 1 | |

| RT > 0.75 s (average of a normal person) | 0 | ||

| H-3 | Alcohol rate (driver) ≤ 0.25 mg/L (Limit in Spain) | 1 | |

| Alcohol rate (driver) > 0.25 mg/L (Limit in Spain) | 0 | ||

| H-4 | Driver without drugs in their system | 1 | |

| Driver with drugs in their system | 0 | ||

| H-5 | Alcohol rate (pedestrian) ≤ 0.25 mg/L | 1 | |

| Alcohol rate (pedestrian) > 0.25 mg/L | 0 | ||

| H-6 | Pedestrian without drugs in their system | 1 | |

| Pedestrian with drugs in their system | 0 | ||

| Technological | T-1 | Expired periodic technical inspection of the vehicle | 1 |

| Current periodic technical inspection of the vehicle | 0 | ||

| T-2 | Pedestrian clothing color with high visibility | 1 | |

| Pedestrian clothing color with low visibility | 0 | ||

| Structural | S-1 | At a pedestrian crossing or its influence area (approx. 5 m) | 1 |

| Outside pedestrian crossing or its influence area (approx. 5 m) | 0 | ||

| S-2 | During the day and/or without glare and/or sufficiently illuminated road | 1 | |

| At night and/or with glare and/or insufficiently illuminated road | 0 | ||

| Normative | N-1 | Expired or without driving license | 1 |

| Current or with driving license | 0 | ||

| N-2 | Vehicle speed ≤ Speed limit of the road | 1 | |

| Vehicle speed > Speed limit of the road | 0 | ||

| N-3 | Driving no using mobile | 1 | |

| Driving using mobile when pedestrian crash occurs, or moments before | 0 | ||

| N-4 | Pedestrian crosses using mobile or with music headphones | 1 | |

| Pedestrian crosses no using mobile or without music headphones | 0 |

| Category | Responsibility (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Driver | Pedestrian | |

| A | 100 | 0 |

| B | 0 | 100 |

| C | 75 | 25 |

| D | 25 | 75 |

| E | 50 | 50 |

| Description | Features |

|---|---|

| Inputs variables | 14 |

| Outputs variables | 5 |

| Number of Layers | 3 |

| Hidden Layers | 1 |

| Number of neurons in each layer | 14, 5, 5 |

| Training Type | Supervised |

| Training Algorithm | LM |

| Transfer Function | Log-Sigmoid |

| Train | %75 (382) |

| Validation | %25 (128) |

| Model | MF1S | BACC | κ |

|---|---|---|---|

| MLP75-25.opt | 0.7536 | 0.7976 | 0.7991 |

| Data Set | MLP75-25 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Matches (%) | Mismatches (%) | ||

| Band 2/Unreliable | Band 3/Unclear | ||

| LPB | 77.71 | 12.46 | 9.83 |

| SJ | 89.97 | 4.86 | 5.17 |

| Category | MLP75-25 | MLP75-25.opt | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Data Set (%) | Questionable Attributions About Original Data Set (%) | Reprocessing Data Set (%) | Questionable Attributions About Reprocessing Data Set (%) | |

| A | 61.71 | 1.38 | 58.45 | 0.96 |

| B | 10.51 | 0.61 | 11.66 | 0.67 |

| C | 9.67 | 3.91 | 8.62 | 7.70 |

| D | 10.37 | 1.32 | 12.06 | 1.48 |

| E | 7.75 | 30.24 | 9.21 | 31.35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Moreno-Sanfélix, A.; Gragera-Peña, F.C.; Jaramillo-Morán, M.A. Improving the Level of Responsibility Classification for Pedestrian Crashes with the Multilayer Perceptron Model. Urban Sci. 2026, 10, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10020068

Moreno-Sanfélix A, Gragera-Peña FC, Jaramillo-Morán MA. Improving the Level of Responsibility Classification for Pedestrian Crashes with the Multilayer Perceptron Model. Urban Science. 2026; 10(2):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10020068

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoreno-Sanfélix, Alejandro, F. Consuelo Gragera-Peña, and Miguel A. Jaramillo-Morán. 2026. "Improving the Level of Responsibility Classification for Pedestrian Crashes with the Multilayer Perceptron Model" Urban Science 10, no. 2: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10020068

APA StyleMoreno-Sanfélix, A., Gragera-Peña, F. C., & Jaramillo-Morán, M. A. (2026). Improving the Level of Responsibility Classification for Pedestrian Crashes with the Multilayer Perceptron Model. Urban Science, 10(2), 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10020068