1. Introduction

Over recent decades, community gardening has emerged as a prominent social and environmental practice in urban areas across the globe [

1,

2]. Broadly defined as the collective cultivation of land by city residents for purposes such as food production, ornamental gardening, or cultural expression, community gardens extend beyond mere spaces of production [

3,

4]. They serve as sites of social interaction, experiential learning, and identity formation [

5]. An expanding body of academic research highlights their potential to strengthen neighborhood cohesion, foster civic engagement, enhance food security, and support ecological resilience in increasingly dense and resource-constrained urban environments [

6,

7]. For urban inhabitants, community gardens offer a unique opportunity to reestablish direct connections with land and nature while also navigating norms of cooperation, trust, and community belonging [

8].

Despite these acknowledged advantages, community gardening is neither a universal nor a homogenous practice. The findings indicate that while some individuals are willing to participate in this initiative, others, despite their lack of interest, are not opposed to the idea in urban settings [

9,

10]. The reluctance of citizens to participate in community gardens can significantly impact the sustainability of such initiatives within urban environments [

11]. This issue is particularly relevant in densely populated cities, such as Tehran, where there is a lack of natural forest cover and insufficient urban green space [

8]. In Tehran, the concept of creating shared community farms and gardens has been proposed for over a decade. However, field surveys and organizational assessments indicate that this idea has not been successful in practice. Advancing and promoting this urban green initiative necessitates a comprehensive understanding of the factors that influence citizens’ acceptance of such programs.

In Western world cities, community gardens are frequently associated with grassroots activism, migrant inclusion, and environmental justice [

12,

13]. Conversely, in East Asia, such initiatives are often spearheaded by municipal authorities as components of formal urban greening strategies [

9,

10]. In contrast, community gardening in the Middle East, particularly in Iran, remains a novel and relatively underexplored phenomenon. However, studies on community gardens have been widely conducted in North America, Europe, and East Asia and predominantly focused on their various functions, such as environmental [

14,

15] or social impacts [

16,

17]. There exists a research gap regarding the factors that influence citizens’ acceptance of this initiative, particularly in Iran and the broader Middle Eastern region. These areas limited natural green spaces in cities and experienced rapid growth and development that host a significant number of migrants from regions with a history of agriculture or gardening. Existing Iranian studies focus largely on environmental roles of gardens, such as air pollution mitigation or microclimate regulation [

8], or on social benefits such as neighborhood interaction [

18]. However, almost no empirical research examines behavioral determinants of participation, the psychological mechanisms motivating citizens, or the cultural and migration-related factors that shape acceptance of community gardening. Similarly, Middle Eastern studies rarely integrate formal behavioral models, and most lack theory-driven frameworks. This gap leaves planners and policymakers without evidence on why citizens may or may not engage in community gardening and how psychological, emotional, or collective motivations operate in dense, rapidly urbanizing Middle Eastern contexts. This study aims to address the existing research gap by systematically examining the behavioral factors that influence the acceptance of community gardens and the willingness of citizens to engage in such initiatives.

This study was conducted to bridge this research gap. By identifying the determinants of citizens’ willingness to participate, this research seeks to (1) identify the psychological, emotional, and social factors that shape citizens’ willingness to participate in community gardening in Tehran; (2) integrate three major behavioral theories including environmental psychology, social cognitive theory, and environmental identity theory into a unified conceptual framework tailored to the urban context; and (3) empirically test this model using structural equation modeling to determine the strongest predictors of participation.

The findings of this study will contribute to the theoretical framework surrounding urban sustainability and community engagement by exploring the social dimensions of this urban green initiative. This exploration will enhance our understanding of the motivations and barriers that shape public attitudes toward community gardens, particularly in densely populated urban environments. Moreover, from a policy and management perspective, the insights garnered from this research can significantly inform urban planners and local government officials. By utilizing the findings, policymakers can design targeted promotion and development programs for community gardens that align with the specific needs and preferences of citizens. Such programs may include educational campaigns, community outreach initiatives, and collaborative planning efforts that encourage active participation from diverse community members. Ultimately, this study seeks not only to advance academic discourse on urban green initiatives but also to provide practical recommendations that can facilitate increased citizen engagement. By fostering a greater understanding of the factors that influence acceptance, urban managers can create more inclusive and sustainable community gardening initiatives that contribute to enhanced quality of life in urban areas.

Conceptual Foundation

Community gardening provides a rich context for exploring the psychological and cultural determinants of civic environmental participation. Understanding citizens’ willingness to participate in community gardening requires examining not only situational or demographic characteristics but also deeper cognitive, emotional, and experiential processes that underlie behavioral motivation. Drawing upon environmental psychology, social cognitive theory [

19], and environmental identity theory [

20], this study develops an integrative model. This model conceptualizes participation in community gardening as the outcome of interrelated memory-based, cognitive, and emotional mechanisms. This integration allows this study to conceptualize community-gardening participation as a multi-domain behavior. Environmental psychology provides the affective and restorative dimensions (connectedness to nature; psychological restoration). Social cognitive theory contributes the cognitive–motivational structures (self-efficacy; outcome expectancy). Environmental identity theory contributes the memory-based and identity-rooted dimensions (childhood nature experience; identity continuity). Together, these theories form a single conceptual framework in which experiential memories shape identity, identity strengthens emotional and cognitive appraisals, and these combined forces generate intention toward community-based environmental action. The developed framework of study assumes that the willingness to engage in community gardening is constructed through both rational evaluations and affective experiences. These factors are embedded within the individual’s lifelong interactions with nature and social environments. Cognitive factors capture the individual’s appraisals of ability and expected benefits. Emotional factors reflect affective bonds, empathy, and psychological rewards; and memory-based factors represent formative experiences and familial influences that shape enduring environmental orientations. The research model was developed with six independent variables, including childhood nature experience, connectedness to nature, self-efficacy, outcome expectancy, psychological restoration, and collective environmental responsibility.

Research in environmental psychology consistently demonstrates that early exposure to natural environments is a powerful antecedent of pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors in adulthood [

21,

22]. Childhood nature experiences foster emotional comfort, curiosity, and a sense of competence in interacting with living systems [

23]. In contexts such as Tehran, where many adults retain memories of rural or agricultural lifestyles, such formative experiences act as deep cognitive and emotional anchors that shape current receptivity to urban green initiatives [

24]. This factor can also shape memory-based environmental identity, which refers to the integration of accumulated experiences with nature into one’s self-concept [

25]. Thus, individuals who spent part of their childhood engaging with gardens, farms, or natural landscapes are likely to perceive community gardening as both familiar and meaningful [

26]. These experiences, as prior mastery and enjoyment of nature-based activities, reduce psychological barriers to participation [

27]. In the context of community gardening, such an identity not only predicts positive emotional responses but also strengthens moral obligation and behavioral intention. Moreover, environmental identity mediates the influence of childhood on current psychological orientations, translating memories into enduring motivations to reconnect with nature in urban life.

Connectedness to nature represents an individual’s enduring emotional and cognitive sense of belonging to the natural world [

28]. It reflects the degree to which people perceive themselves as part of nature rather than separate from it, encompassing affective attachment, identity integration, and ecological self-awareness [

29]. As an internalized orientation, it shapes how individuals interpret and respond to environmental experiences, influencing both attitudes and behaviors toward sustainability [

30,

31]. In this research, connectedness to nature provides a psychological link that transforms gardening from a functional or recreational activity into an expression of identity and care for the environment. Individuals with stronger connectedness to nature are more likely to perceive urban gardens as significant spaces that reaffirm their sense of unity with the ecosystem [

32,

33]. Integrating this variable enhances the explanatory power of the framework by capturing a core dimension of human–nature relations that underlies both cognitive evaluations and emotional motivations. In densely urbanized contexts like Tehran, fostering connectedness to nature can play a pivotal role in revitalizing ecological consciousness and promoting participation in collective green initiatives.

Derived from [

19] ocial cognitive theory, self-efficacy reflects individuals’ belief in their ability to successfully perform specific behaviors. The ability of individuals to perform a behavior is also emphasized in other theories, such as the theory of planned behavior [

34], highlighting the significance of this factor. Various studies in the context of forestry and environmental actions have demonstrated the positive and significant impact of this factor [

35,

36]. Research also confirmed the role of this factor in forest-agriculture operation of agroforestry [

37]. In community gardening, self-efficacy pertains to perceived competence in gardening tasks, problem-solving, and collaboration. It is a crucial determinant of both behavioral initiation and persistence, influencing whether individuals translate favorable attitudes into action [

38]. High self-efficacy enhances perceived control and fosters positive emotions such as enjoyment and satisfaction.

Outcome expectancy represents the belief that performing a behavior will lead to desirable outcomes [

39]. It integrates both personal and collective benefits, such as access to direct or indirect economic benefits, social urban aspects, environmental sustainability, and psychological well-being [

40,

41,

42]. When individuals perceive that community gardening can improve their quality of life or community resilience, their motivation to engage increases. Outcome expectancy in environmental behavior refers to the belief that one’s actions will have a meaningful impact on achieving desired environmental outcomes, such as mitigating climate change or improving ecological health. It plays a crucial moderating role in translating intentions, attitudes, and concerns into actual pro-environmental behavior [

43,

44]. Positive outcome expectancies also elevate emotional engagement, heightening affective enjoyment and strengthening the sense of purpose derived from participation. In line with expectancy-value theory, individuals are more likely to act when they anticipate meaningful and valued outcomes [

45].

The restorative benefits of contact with nature are well documented in attention restoration theory [

46] and stress recovery theory [

47]. Research has shown that engaging in gardening or agricultural activities [

48], as well as spending time in green spaces [

49,

50], can significantly reduce stress and enhance individuals’ attentional recovery. Urban environments, due to their specific environmental conditions, are often associated with high levels of stress and psychological pressure [

51]. For residents of densely populated and polluted cities such as Tehran, the perception of stress relief through gardening may serve as a key emotional incentive [

52]. However, activities related to urban green spaces, such as gardening and spending time in these areas, have been found to positively impact individuals [

53]. Consequently, these benefits can serve as a motivation for encouraging people to participate in community gardening initiatives within cities.

Collective environmental responsibility refers to the shared sense of moral duty and communal obligation individuals feel toward protecting and improving their local environment [

54]. It extends beyond personal environmental concern to encompass a collective awareness that sustainable outcomes depend on joint action and mutual accountability [

55]. When individuals internalize a sense of shared stewardship, they are more likely to engage in behaviors that contribute to the collective good and support inclusive participation [

56]. Collective environmental responsibility aligns with social norm theory, which suggests that moral and cooperative norms within communities strengthen pro-environmental engagement [

57]. Within the context of community gardening, this construct highlights how participation is driven not only by self-interest or individual well-being but also by the recognition that ecological challenges require cooperative solutions. In cities like Tehran, where rapid urbanization has weakened communal ties to nature, fostering this sense of shared responsibility can transform community gardens into platforms for civic environmental action. By integrating collective environmental responsibility into the framework, the study captures a critical social driver that connects individual intentions with community-level environmental outcomes and sustainable urban transformation.

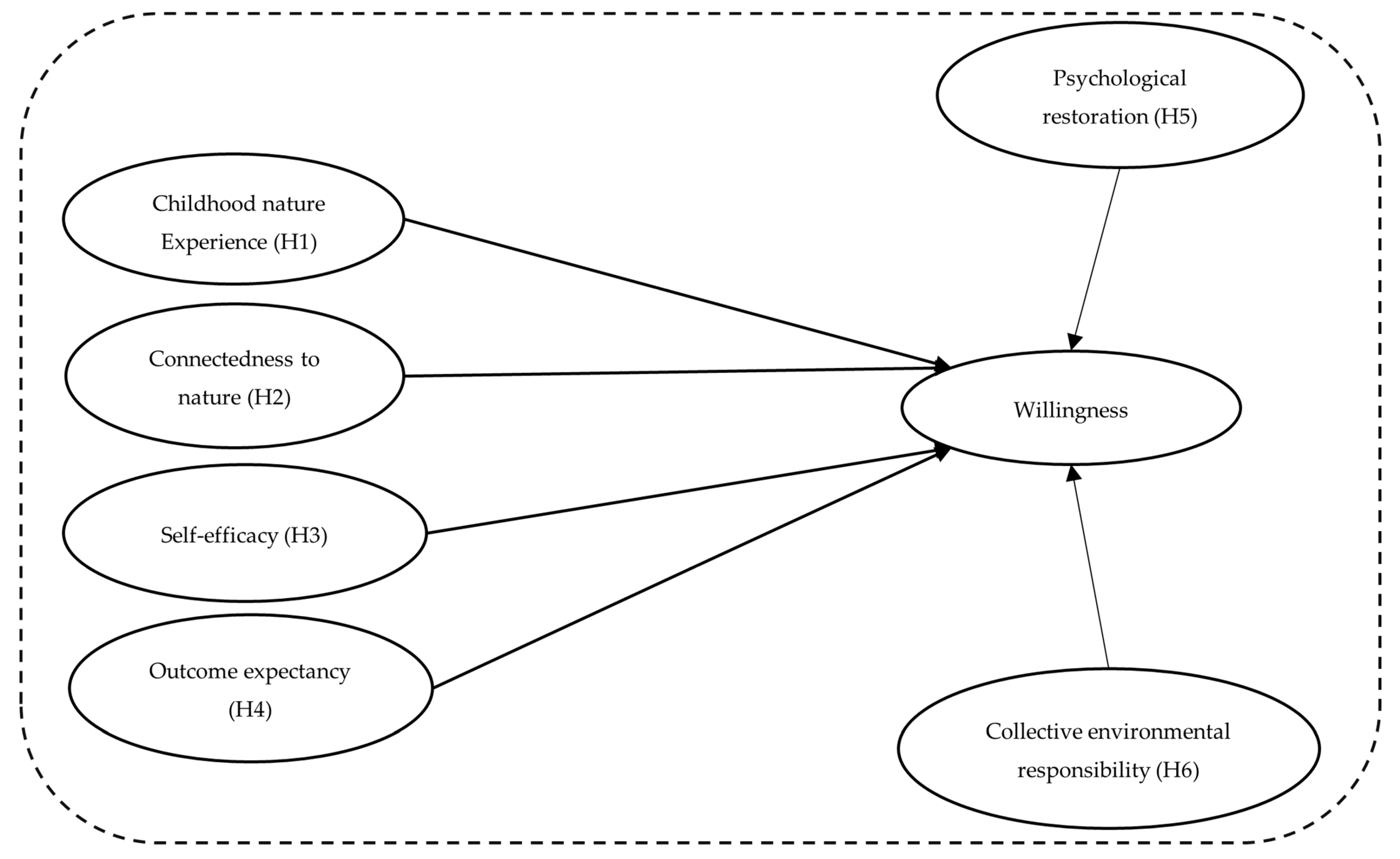

The research hypotheses were formulated based on the above variables and the scientific rationale derived from previous studies. The research hypotheses are summarized in

Table 1 and conceptual framework is illustrated graphically in

Figure 1.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

The research hypotheses were explored in Tehran, the capital city of Iran, with special properties that make this city an appropriate case study. Tehran, with over nine million residents, exemplifies the challenges of contemporary urbanization in the Global South. Air pollution, water scarcity, and limited public green spaces have all undermined the city’s livability [

58]. Municipal initiatives have prioritized large-scale parks and roadside landscaping, yet neighborhood-level, participatory green spaces remain limited [

59]. At the same time, Tehran’s population is marked by its history of rural-to-urban migration. Many families maintain strong connections to villages and rural hometowns, where gardening and farming have long been central to livelihoods and cultural identity. For older generations, memories of orchards, vineyards, and family plots are powerful, while younger residents often encounter these traditions through intergenerational narratives. This rural heritage creates a cultural reservoir of gardening practices and meanings, even within the highly urbanized context of Tehran.

2.2. Participants and Sampling Method

The statistical population of this study consisted of all citizens aged 18 years and above residing in Tehran. The sample size was determined using [

60] table, which suggested a minimum of 384 participants for the given population size. However, considering the city’s vast area and dense population, a larger number of respondents were surveyed. After excluding incomplete questionnaires, a total of 416 valid responses were retained for analysis. A multistage cluster sampling method was employed for data collection. Initially, eight districts with appropriate geographical distribution were selected from among Tehran’s 22 municipal regions as the first-level clusters. Subsequently, within each selected district, urban neighborhoods were identified as the next-level clusters. From these clusters, respondents were randomly selected to ensure representativeness across different parts of the city.

2.3. Data of Research

The research data were collected using a structured questionnaire specifically designed for this study. The questionnaire was developed to measure the seven key variables of the research (

Table 2). The items were constructed based on the theoretical foundations of each variable and a comprehensive review of relevant literature. The questionnaire was developed in English and translated into Persian (Farsi) using a forward–backward translation procedure to ensure semantic equivalence. The measurement scales used in this study were adapted from previously validated instruments in environmental psychology and pro-environmental behavior research (

Table 2). Item wording was slightly modified to fit the context of community gardening and the urban setting of Tehran, while preserving the original conceptual meaning. After drafting the initial set of items, a panel of six experts specializing in environmental science, sociology, forestry, and agriculture reviewed the questionnaire and provided feedback. Based on their suggestions, the items were revised and resubmitted to the experts for further evaluation. The final version, consisting of 29 items, was approved by the expert panel. Following this stage, a pre-test was conducted with 30 participants to assess the reliability and clarity of the instrument. The results confirmed the questionnaire’s reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha exceeding 0.7. The finalized version was then used for data collection [

61].

Data were collected through in-person administration of the questionnaire. A trained team of three field researchers, who had been thoroughly instructed on the purpose, content, and administration procedures, facilitated the process. All constructs were operationalized using multi-item Likert-type scales with demonstrated reliability in prior studies [

72,

73]. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards for research involving human participants. Prior to data collection, all participants were informed about the objectives of the study, the voluntary nature of participation, and their right to withdraw at any time without any consequences. Written informed consent was obtained from all respondents before participation. The introduction of the questionnaire clearly outlined the purpose of the research, the expected time commitment, and assurances of anonymity and confidentiality. No personally identifiable information was collected. All data were securely stored, accessed only by the research team, and used exclusively for academic and research purposes. This procedure was approved by Research Ethic Committees of Lorestan University of Medical Science under number IR.LUMS.REC.1402.324. Assistance was provided to respondents who required help in completing the questionnaire. Data collection took place during July and August 2025.

2.4. Data Analysis of Research

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was employed to analyze the data, as it offers a comprehensive and robust statistical approach for examining complex relationships among multiple latent and observed variables simultaneously. SEM is particularly suitable for this study because it allows the integration of measurement and structural models, thereby enabling the assessment of both the reliability of measurement instruments and the strength of hypothesized causal relationships among the constructs [

74]. This analytical approach is widely recognized in social and environmental behavioral research for its capacity to test theoretical models grounded in complex human–environment interactions, making it an appropriate and rigorous method for the present study.

2.4.1. Reliability and Validity

To ensure the reliability and validity of the measurement model, several statistical indicators were examined, including Cronbach’s alpha (α), Composite Reliability (CR), Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio (HTMT), and Rho_A. Cronbach’s alpha and CR were used to assess internal consistency reliability. Values of Cronbach’s alpha and CR above the recommended threshold of 0.70 indicate satisfactory reliability, confirming that the items for each construct consistently measure the same underlying concept [

61]. Convergent validity was evaluated using the AVE, with values exceeding 0.50 suggesting that each construct explains more than half of the variance of its indicators. The Rho_A coefficient was also examined as a complementary reliability measure, providing a more accurate estimation of construct reliability compared to Cronbach’s alpha. Rho_A values above 0.70 were considered acceptable. Discriminant validity was assessed using the HTMT criterion, which evaluates the distinctiveness of constructs. All HTMT values were below the conservative threshold of 0.85, indicating that each latent construct is empirically distinct from the others.

2.4.2. Model Fit Assessment

Model fit was assessed using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). The standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), squared Euclidean distance (d_ULS), geodesic distance (d_G), chi-square statistic, and normed fit index (NFI) were calculated for both the saturated and estimated models to evaluate overall model adequacy. These indices were used to examine the discrepancy between the observed and model-implied correlation matrices and to confirm the global fit of the proposed structural model.

2.4.3. Structural Model and Hypotheses Testing

The structural model was assessed to examine the hypothesized relationships among the study’s latent constructs. After confirming the adequacy of the measurement model, the structural model was tested using the path coefficients and coefficient of determination (R2). The path coefficients represent the strength and direction of the relationships between constructs, allowing for the empirical testing of the proposed hypotheses. The statistical significance of each path was determined using a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 resamples, which provides robust standard errors and confidence intervals. The coefficient of determination (R2) was used to evaluate the explanatory power of the model, with higher R2 values indicating stronger predictive ability of the independent variables on the dependent constructs. Data were analyzed using Smart PLS3 for structural model and SPSS23 for demographic data.

3. Results

3.1. Profile of Participants of Research

The demographic profile of the respondents is presented in

Table 3. A total of 416 individuals participated in the survey, comprising 48% females and 52% males, indicating a relatively balanced gender distribution. In terms of age, the largest group of respondents (27%) fell within the 40–50-year age range, followed by those aged 50–60 years (24%) and above 60 years (18%). Younger participants below 30 years constituted 14% of the sample, while 17% were between 30 and 40 years old. Regarding marital status, the majority of respondents were married (67%), whereas 33% were single. The educational background of participants showed considerable diversity. About 40% of respondents held school-level degrees, 27% possessed a diploma, and 21% had a university degree. Only 12% of the participants were illiterate. Overall, the sample represents a wide range of socio-demographic backgrounds, suitable for analyzing variations in attitudes and behaviors across different social groups.

3.2. Results of Reliability and Validity

The results for reliability and validity of the measurement model are shown in

Table 4. The results show that all constructs demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.844 to 0.936. These values are well above the commonly accepted threshold of 0.70, indicating strong reliability among the items representing each construct [

61]. Similarly, the Rho_A coefficients, which provide a more accurate estimate of construct reliability, varied between 0.845 and 0.938, further confirming the robustness of the measurement model. The CR values ranged from 0.895 to 0.954, exceeding the minimum acceptable level of 0.70 and demonstrating high internal consistency across all latent variables [

75]. Convergent validity was established through the AVE, which ranged from 0.681 to 0.838, well above the recommended threshold of 0.50, suggesting that each construct accounts for a substantial proportion of the variance in its indicators. These findings collectively confirm that the measurement items reliably capture their intended constructs, and the model exhibits satisfactory convergent validity.

Discriminant validity was examined using the HTMT criterion. As shown in

Table 5, all HTMT values were below the conservative threshold of 0.85, ranging from 0.231 to 0.591. These results confirm that each construct is empirically distinct, and no multicollinearity issues exist among latent variables. Overall, the results demonstrate that the measurement model possesses strong internal consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant validity, ensuring the appropriateness of the constructs for subsequent structural model evaluation.

3.3. Results of Model Fit Assessment

The saturated and estimated models yield identical fit indices, indicating stable estimation (

Table 6). The SRMR value (0.043) is below the recommended threshold of 0.08, demonstrating good model fit. The d_ULS (0.794) and d_G (0.355) discrepancy measures are within acceptable ranges, suggesting no model misspecification. Although the Chi-square statistic (879.354) is sensitive to sample size and not a primary fit indicator in PLS-SEM, its consistency across models confirms adequate reproduction of the empirical covariance structure. The NFI value (0.887) approaches the commonly accepted 0.90 threshold, indicating an overall acceptable level of model fit.

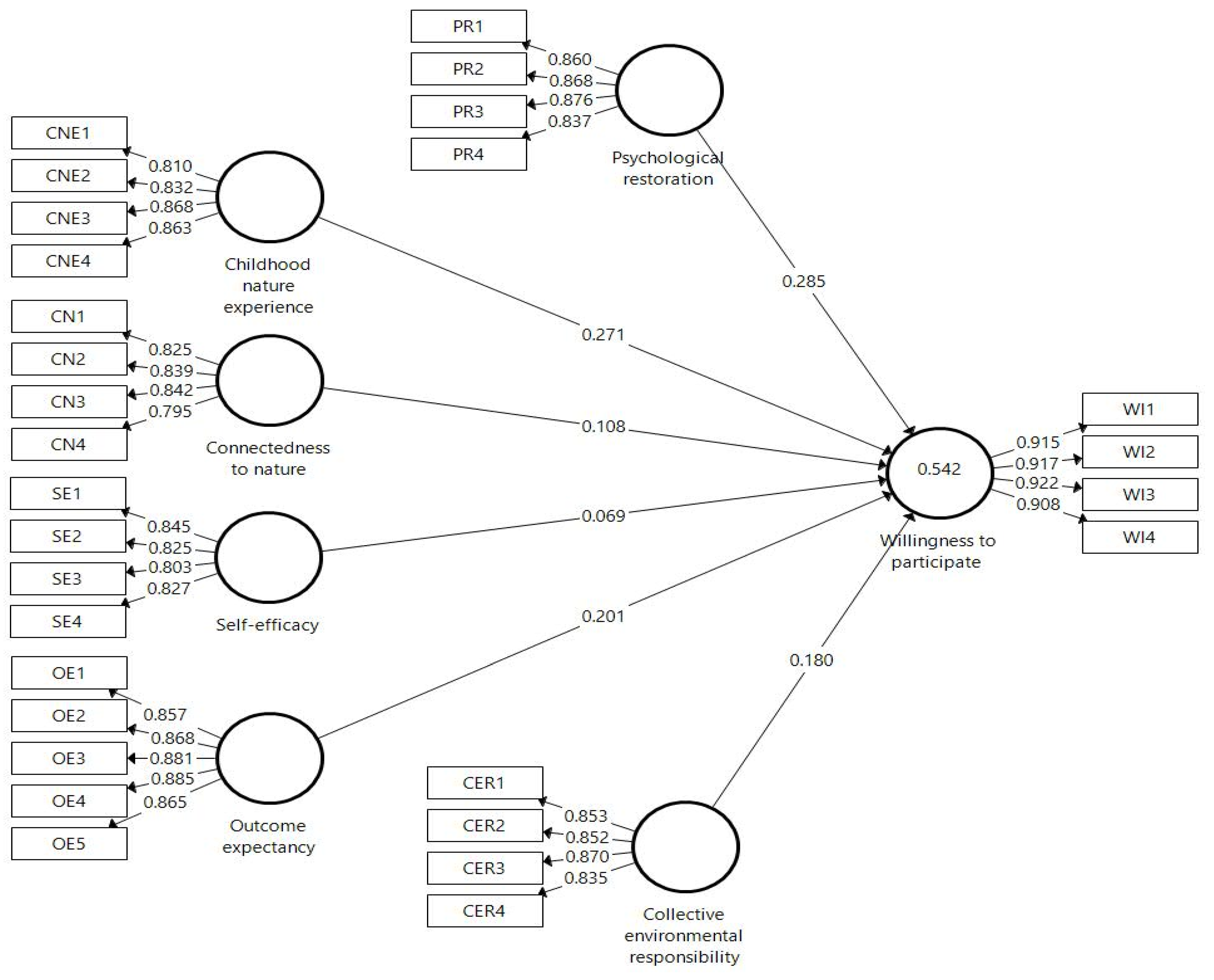

3.4. Results of Structural Model and Hypotheses Testing

To assess the model’s explanatory power, the coefficient of determination (R

2) was examined. The model accounted for a substantial proportion of variance in willingness to participate in community gardening initiative (R

2 = 0.542) (

Figure 2), indicating that 54.2% of the variability in citizens’ participation intentions is jointly explained by the cognitive, emotional, and social-moral predictors. This level of explanatory power is considered high in behavioral research, confirming the adequacy of the proposed model. The adjusted R

2 (0.535) is very close to the R

2 value, suggesting that the model is not overfitted and that the included predictors make a meaningful contribution. In addition, the cross-validated redundancy (Q

2) value of 0.424 is well above zero, indicating strong predictive relevance of the model for willingness to participate (

Table 7).

Table 8 presents the results of hypothesis testing. Of the six proposed hypotheses, five were supported at the 0.05 significance level. Childhood nature experience (H1) had a significant positive effect on willingness (β = 0.26, t = 7.80,

p < 0.001), suggesting that early interactions with natural environments strengthen pro-environmental orientations in adulthood. Individuals with rich nature-related memories are more likely to perceive community gardening as a familiar and rewarding activity, which aligns with environmental socialization theory. Connectedness to nature (H2) also exhibited a positive and significant influence on Willingness to Participate (β = 0.11, t = 3.00,

p < 0.01). This finding indicates that individuals who perceive themselves as part of nature are more inclined to engage in activities that express ecological belonging and care. Similarly, outcome expectancy (H4) positively affected willingness (β = 0.20, t = 4.67,

p < 0.001), emphasizing that expected personal and collective benefits such as social interaction, psychological well-being, and urban greening serve as strong behavioral motivators.

The path from psychological restoration (H5) to willingness to participate was also positive and statistically significant (β = 0.28, t = 7.53, p < 0.001), confirming that perceived stress reduction and mental recovery derived from gardening experiences act as crucial emotional incentives for participation. Collective environmental responsibility (H6) demonstrated a significant positive relationship with willingness (β = 0.15, t = 4.93, p < 0.001), indicating that a shared moral sense of stewardship toward the local environment fosters cooperative engagement in community-based ecological initiatives. Conversely, the effect of self-efficacy (H3) on willingness was not statistically significant (β = 0.06, t = 1.87, p = 0.061). Although individuals may feel capable of performing gardening tasks, this perceived competence alone does not necessarily translate into active participation when emotional and collective motives are more salient.

The results support a multidimensional understanding of citizens’ willingness to participate in community gardening. Behavioral engagement is shaped not merely by perceived ability or rational evaluation of outcomes but also by deeply rooted emotional attachments, restorative experiences, and collective environmental values. These findings reinforce the integrative nature of the proposed framework, bridging cognitive, affective, and normative dimensions of environmental participation and providing a robust empirical foundation for promoting community-based sustainability initiatives in densely urbanized contexts.

These conclusions are supported by robust SEM diagnostics, including substantial explained variance, strong predictive relevance, and satisfactory reliability and validity measures, ensuring that the findings are evidence-based rather than descriptive.

4. Discussion

This study was conducted to answer the following research question: Which psychological, experiential, and social factors most strongly explain citizens’ willingness to participate in community gardening in a densely populated urban context? By integrating environmental psychology, social cognitive theory, and environmental identity theory, the study sought to identify whether participation is driven primarily by perceived capability, expected outcomes, emotional restoration, formative nature experiences, or collective moral responsibility. The results validate the proposed framework, highlighting the interplay between experiential, cognitive, affective, and normative dimensions of pro-environmental behavior. The significant relationships observed for childhood nature experience, connectedness to nature, outcome expectancy, psychological restoration, and collective environmental responsibility underscore the multifaceted nature of engagement in urban green initiatives. In contrast, the non-significant effect of self-efficacy suggests that perceived competence alone is insufficient to motivate participation when deeper emotional and social drivers are at play. Together, these findings extend existing theories by revealing that participation in community gardens in dense urban contexts such as Tehran is shaped as much by personal meaning and collective values as by perceived behavioral control.

In direct response to the first research hypothesis, the results show that childhood nature experience is a key determinant of willingness to participate. This finding aligns with previous studies showing that childhood exposure to natural environments fosters environmental identity, empathy, and a sense of stewardship [

31,

76]. In Tehran’s context, a substantial proportion of participants were middle-aged to older adults (51% aged 40–60 years). Many residents retain rural roots or intergenerational memories of gardening shaped by large-scale rural–urban migration during recent periods of social and national transformation in Iran. These formative experiences, often linked to structural changes such as agrarian restructuring, urban expansion, and rapid socioeconomic shifts, function as powerful cognitive and emotional anchors that continue to influence adult attitudes toward community-based green initiatives. Such formative encounters cultivate familiarity and confidence in nature-related activities, reducing perceived barriers to participation [

77]. Consistent with the environmental socialization framework, these results emphasize that environmental behaviors are not solely learned but deeply embodied through experiential learning [

78]. Hence, policies that encourage family-oriented gardening programs and environmental education for children can have lasting behavioral impacts. The strong predictive power of this construct also supports the notion that reconnecting urban populations with their ecological memories may be a crucial pathway toward fostering community engagement in sustainability initiatives.

The positive effect of connectedness to nature (H2) reinforces the importance of emotional and identity-based bonds in shaping pro-environmental actions. This result corresponds with earlier findings [

23,

33], which demonstrated that individuals with stronger nature connectedness are more likely to engage in environmentally responsible behaviors. In the context of Tehran, a highly urbanized and often stressful environment, this sense of unity with nature provides psychological compensation for ecological deprivation. Individuals who internalize nature as part of their self-concept perceive gardening not merely as a leisure activity but as a means of expressing ecological identity and moral responsibility [

79]. The relatively moderate strength of this relationship compared to other constructs suggests that while emotional connectedness is vital, its behavioral translation depends on the availability of accessible, safe, and socially supported urban green spaces. Strengthening connectedness to nature through urban greening, environmental art, and participatory green planning may therefore enhance both ecological awareness and civic participation.

The non-significant relationship between self-efficacy (H3) and willingness to participate suggests that perceived competence alone does not strongly predict behavioral engagement in community gardening. Although prior studies [

68,

80] identified self-efficacy as a key determinant of environmental action, its weaker effect here may reflect contextual and cultural factors. In Tehran, practical constraints such as land access, institutional support, or limited gardening infrastructure may overshadow individuals’ confidence in their abilities. Moreover, the dominance of affective and social motives such as restoration and collective responsibility may reduce the salience of self-efficacy in predicting participation. This finding implies that, in collective and socially embedded environmental practices, personal capability perceptions play a secondary role to emotional meaning and social cohesion. Nonetheless, enhancing self-efficacy through training workshops, peer learning, and community mentoring can still indirectly strengthen engagement by improving perceived behavioral control and reinforcing collective confidence. The non-significant effect of self-efficacy warrants deeper consideration. Unlike individualistic environmental behaviors, community gardening is a collective, place-dependent activity that relies heavily on institutional access, social coordination, and shared infrastructure. In such contexts, perceived individual competence may be overshadowed by external constraints, such as land availability, organizational support, and municipal facilitation. Moreover, when participation is emotionally and morally motivated, as indicated by the strong effects of psychological restoration and collective environmental responsibility, perceived ability becomes a secondary concern. This finding suggests a contextual boundary condition for social cognitive theory, indicating that self-efficacy may be less influential in collective, community-based environmental practices than in individually performed behaviors.

The positive and significant relationship between outcome expectancy (H4) and willingness to participate highlights the motivational role of perceived benefits in driving engagement. Consistent with expectancy-value theory [

45,

81], individuals act when they believe their participation will yield meaningful outcomes. Similar findings have been reported in research [

41,

43], emphasizing that the anticipation of personal well-being, community cohesion, and environmental improvement fosters behavioral commitment. In Tehran, where residents face urban stressors such as pollution and limited green space, the expectation of tangible physical and psychological gains from gardening becomes a key driver. Moreover, collective benefits such as enhanced neighborhood relationships further strengthen participation through social reinforcement. The result suggests that emphasizing the multidimensional benefits of community gardening in policy communication such as health, social inclusion, and food resilience, can amplify citizens’ motivation. Therefore, enhancing visibility of successful community gardens and framing participation as both self-beneficial and collectively meaningful may increase public willingness to engage.

The strong positive influence of psychological restoration (H5) on willingness to participate confirms the therapeutic and stress-reducing value of nature-based activities. This finding is consistent with attention restoration theory [

46] (Basu et al. 2019) and stress recovery theory [

47], which demonstrate that exposure to natural settings supports emotional well-being and cognitive recovery. Studies [

50] similarly observed that gardening enhances relaxation and mitigates urban stress. For Tehran residents, often exposed to environmental noise, congestion, and limited natural scenery, the restorative quality of community gardens provides both personal relief and social reconnection. This emotional reward translates into sustained participation, as individuals seek consistent contact with calming and meaningful environments. The magnitude of this effect suggests that restoration acts not only as an outcome but also as a motivational antecedent of engagement. Incorporating restorative design principles such as greenery diversity, sensory engagement, and tranquil spaces into community gardens can therefore strengthen both participation and mental well-being outcomes.

The significant positive relationship between collective environmental responsibility (H6) and willingness to participate underscores the moral and social foundations of environmental behavior. This result aligns with findings from [

54,

57], which emphasized the role of moral obligation and community norms in promoting cooperative environmental actions. In Tehran’s social context, where collective identity remains strong despite rapid urbanization, shared responsibility for urban sustainability becomes a meaningful motivator. When individuals perceive that maintaining green spaces is a collective duty, they are more likely to collaborate and contribute time and effort to communal gardening projects [

82]. This outcome supports social norm theory, which posits that perceived group expectations and moral cohesion enhance cooperative behavior. The result also implies that civic engagement strategies emphasizing shared stewardship, mutual accountability, and collective environmental ethics can amplify citizens’ involvement. Initiatives such as neighborhood environmental committees, co-management of gardens, and participatory green planning can institutionalize this collective sense of responsibility.

5. Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implication

This study develops and empirically validates an integrative theoretical framework that advances current understanding of citizens’ participation in urban community gardening by synthesizing insights from environmental psychology, social cognitive theory, and environmental identity theory. The framework conceptualizes willingness to participate in community gardening as a multidimensional construct shaped by the interaction of experiential, cognitive, affective, and normative processes. Unlike traditional behavioral models—such as the theory of planned behavior, which emphasizes rational evaluation and perceived control—the present framework highlights the emotional, identity-based, and moral dimensions that underpin environmental participation. By integrating constructs such as childhood nature experience, connectedness to nature, psychological restoration, and collective environmental responsibility, the model extends behavioral theory beyond intention-based predictors to include formative memories and social–ethical orientations that are rarely operationalized in urban environmental behavior research.

Theoretically, this study contributes in three major ways. First, it introduces a memory-based pathway linking childhood nature experience to contemporary pro-environmental behavior, demonstrating that early ecological exposure has enduring effects on adult environmental engagement. This perspective complements existing models that often overlook the developmental origins of environmental action, offering a temporal extension of environmental socialization theory. Second, the study advances the emotional and restorative dimensions of participation, illustrating how connectedness to nature and psychological restoration mediate the relationship between urban stress and ecological engagement. This finding enriches the affective branch of environmental psychology by positioning restoration not only as an outcome of green interaction but as a motivational driver for sustained participation. Third, by incorporating collective environmental responsibility, the framework captures the social-moral foundations of environmental behavior, emphasizing that urban sustainability is co-constructed through shared norms and collective agency. This inclusion bridges individual-level psychological models with broader socio-environmental theories of cooperative behavior and civic ecology. Overall, the proposed model provides a more holistic understanding of pro-environmental participation in densely populated cities by connecting cognitive evaluations, emotional affinities, collective values, and formative experiences within a single explanatory system. The findings confirm that participation in community gardening is not merely a matter of perceived capability or utility but a reflection of deeply embedded environmental identity, psychological fulfillment, and communal moral reasoning. Hence, this study not only extends theoretical integration across disciplines but also contributes to developing a more inclusive and human-centered paradigm for explaining environmental engagement in urban contexts.

5.2. Policy and Practical Implications

The results of this study provide several actionable insights for urban policymakers, planners, and local institutions seeking to promote community gardening as a participatory sustainability strategy in densely populated cities. Importantly, the findings indicate that participation is driven less by technical competence and more by emotional, experiential, and collective motivations. This has direct implications for how community gardening initiatives should be designed, communicated, and governed. First, the strong effect of childhood nature experience suggests that long-term participation in urban green initiatives is rooted in early-life exposure to nature. Urban policy should therefore treat community gardening not only as a current land-use intervention but as a long-term investment in environmental socialization. Municipalities can operationalize this by integrating school gardens, youth gardening programs, and intergenerational gardening initiatives into neighborhood planning. Embedding gardening activities within schools, after-school programs, and family-oriented public spaces can help rebuild ecological familiarity among younger urban generations and create a future constituency for participatory green initiatives. Second, the significant influence of connectedness to nature and psychological restoration highlights the importance of designing community gardens as emotionally meaningful and restorative environments rather than purely functional spaces. Urban planners should prioritize small-scale, accessible gardens that emphasize sensory engagement, aesthetic quality, and opportunities for relaxation. Design features such as vegetation diversity, shaded seating, water elements, and quiet zones can enhance restorative experiences and strengthen emotional attachment to place. From a policy perspective, this implies that community gardens should be incorporated into public health and well-being strategies, particularly in cities facing high levels of stress, pollution, and social fragmentation.

Third, the positive role of outcome expectancy indicates that citizens are more willing to participate when the benefits of community gardening are visible, credible, and multidimensional. Local governments and community organizations should therefore adopt communication strategies that clearly demonstrate tangible outcomes, such as improved mental health, stronger neighborhood ties, food provision, and local environmental improvement. Monitoring and publicly sharing indicators of success—such as participation rates, harvest yields, or social events—can reinforce positive expectations and sustain engagement over time. Fourth, the strong effect of collective environmental responsibility underscores that community gardening functions most effectively when framed as a shared civic duty rather than an individual hobby. This finding supports governance models based on co-management and shared stewardship. Policymakers should facilitate participatory governance arrangements, including neighborhood garden committees, resident-led maintenance teams, and collaborative decision-making processes. Instruments such as participatory budgeting, local stewardship agreements, and formal recognition of volunteer contributions can institutionalize collective responsibility and strengthen social ownership of urban green spaces. Finally, the non-significant effect of self-efficacy suggests that limited participation is not primarily due to a lack of skills or confidence, but rather to structural and institutional barriers. Consequently, policy efforts should focus less on individual capability-building alone and more on reducing access barriers, such as limited land availability, unclear regulations, or lack of municipal support. Providing secure land tenure for community gardens, basic infrastructure, tools, and ongoing facilitation can enable participation even among individuals with limited prior experience.

Beyond the immediate study area, these implications contribute to global discussions on urban sustainability by illustrating that meaningful environmental participation emerges not only from rational decision-making but from emotional connection, restorative experience, and collective responsibility. Embedding these psychological and social dimensions into urban policy design can foster deeper public engagement and help cities worldwide transition toward more inclusive, resilient, and ecologically conscious urban futures.

6. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

This study also has some limitations, which must be considered. First, the study employed a cross-sectional survey design, which restricts the ability to infer causality among the examined constructs. Although the use of structural equation modeling enhanced analytical robustness, the relationships identified here represent associations rather than definitive causal pathways. Future research could adopt longitudinal or experimental designs to capture changes in attitudes and behavior over time, particularly to assess how ongoing engagement in community gardening reinforces environmental identity, restoration, and collective responsibility. Second, the data were collected exclusively from residents of Tehran, a city with specific cultural norms, institutional structures, and environmental challenges. These contextual characteristics may limit the generalizability of findings to other cities or countries. Comparative studies across diverse cultural, socioeconomic, and climatic contexts would clarify how environmental participation is shaped by differing cultural values, policy frameworks, and ecological conditions. Replicating this model in both developed and developing urban settings would enhance external validity and support broader theoretical generalization.

Third, the research relied on self-reported data, which may introduce response bias, particularly regarding socially desirable behaviors or retrospective accounts such as childhood nature experiences. Although the instrument demonstrated strong reliability and validity, future research could employ mixed-method approaches, including interviews, ethnographic observation, or longitudinal diaries, to obtain richer, more authentic insights into participants’ experiences and motivations. Additionally, incorporating objective behavioral data such as participation records or observational indicators could reduce subjective bias and increase the precision of behavioral measurement. Fourth, while the model explained a substantial proportion of variance in willingness to participate, it did not account for several contextual and structural factors that may influence engagement. Variables such as social capital, neighborhood attachment, institutional trust, accessibility of green spaces, and perceived municipal support could further enhance explanatory depth. Incorporating these dimensions would allow future frameworks to more accurately capture the interaction between personal psychology and structural enablers of participation. Fifth, the present framework focuses primarily on individual-level psychological and social factors. However, community gardening is inherently embedded in broader institutional and spatial systems. Future research could integrate multi-level analytical approaches to explore how governance models, policy incentives, or urban design influence collective environmental behavior. Such perspectives would connect micro-level motivations to macro-level urban sustainability processes. Sixth, the study concentrated on community gardening as a representative form of civic environmental participation. While this context provides a meaningful case for examining urban engagement, future work could test the framework in other pro-environmental domains such as urban forestry, waste reduction, or participatory energy initiatives to evaluate the transferability of psychological mechanisms across different sustainability practices.

Finally, although the sample size is relatively large, several sampling considerations should be acknowledged. Data collection relied on voluntary participation, which may have introduced self-selection bias, as individuals with higher environmental interest or prior exposure to gardening and green spaces may have been more inclined to participate. As a result, willingness to engage in community gardening may be somewhat overestimated. In addition, while the survey reached respondents across different urban districts, participation was more common among individuals with higher educational attainment, which may reflect differential access to information, time availability, or familiarity with environmental initiatives. The observed demographic patterns suggest that socioeconomic factors may shape both access to and perceptions of community gardening, particularly in densely populated urban contexts. Finally, because participation was based on voluntary response rather than probabilistic sampling, the findings should be interpreted as analytically rather than statistically generalizable. Future research would benefit from stratified or mixed-mode sampling strategies and the explicit integration of socioeconomic indicators to better capture participation inequalities.

7. Conclusions

This study set out to identify the psychological, experiential, and social factors that explain citizens’ willingness to participate in community gardening within a densely populated urban context, addressing a notable gap in the literature on urban green participation in Middle Eastern cities. By integrating environmental psychology, social cognitive theory, and environmental identity perspectives, the research developed and empirically tested a multidimensional behavioral model using structural equation modeling. The findings demonstrate that childhood nature experience, connectedness to nature, outcome expectancy, psychological restoration, and collective environmental responsibility significantly influence willingness to participate in community gardening, while self-efficacy does not exert a statistically significant effect. Together, these factors explain approximately 54% of the variance (R2 = 0.542) in participation willingness, indicating a moderate-to-substantial level of explanatory power for a complex social behavior. This result suggests that while the proposed framework captures key motivational mechanisms, participation in community gardening is also shaped by additional contextual, institutional, and structural factors not included in the present model. The research objectives were fulfilled by empirically demonstrating that participation in community gardening is driven less by perceived individual capability and more by affective, experiential, and collective motivations. In particular, the strong roles of psychological restoration and collective environmental responsibility highlight that engagement in urban green initiatives is closely linked to emotional well-being and shared moral commitments, rather than solely to rational evaluations of ability or skill. These findings extend existing behavioral models by emphasizing the importance of formative nature experiences and social–moral dimensions in shaping urban environmental participation.

Importantly, this study contributes to literature by providing empirical evidence from Tehran, a densely populated city in the Middle East where community gardening remains underexplored. By contextualizing participation within a setting characterized by rapid urbanization, environmental stress, and strong rural–urban cultural legacies, the study directly addresses the identified research gap concerning how citizens in such contexts perceive and engage with participatory urban green initiatives. The results suggest that theories largely developed in Western or East Asian contexts can be meaningfully extended when emotional, memory-based, and collective responsibility constructs are explicitly incorporated. The conclusions should be interpreted in light of several limitations. The cross-sectional design restricts causal inference, and the reliance on self-reported data may introduce response bias. Moreover, although the model explains a substantial portion of participation willingness, nearly half of the variance remains unexplained, indicating the need for future research to incorporate structural variables such as institutional support, accessibility of green spaces, and governance arrangements. Acknowledging these limitations enhances the credibility of the findings and underscores opportunities for further theoretical and empirical refinement.

Overall, this study provides a context-sensitive and empirically grounded understanding of community gardening participation in a densely populated urban environment. Rather than offering definitive prescriptions, it offers evidence-based insights into the psychological and social mechanisms that can inform more inclusive and emotionally responsive urban sustainability strategies.