Promoting Healthier Cities and Communities Through Quantitative Evaluation of Public Open Space per Inhabitant

Abstract

1. Introduction

- According to UN-Habitat, public spaces are grouped into three primary types: streets, open areas, and community facilities. Based on comparative research across cities globally. The recommendation stipulates that 45–50% of urban land should be designated for streets and open public spaces, with 30–35% specifically for streets and sidewalks, and 15–20% for open public spaces, which encompasses both green areas such as parks and hard-surface areas like plazas, squares, and public courtyards [23,24,25].

- In the United States, standards set by the Public Health Bureau and the Department of Housing suggest 18 m2 per capita [19].

- The United Nations recommends a standard of 30 m2 of green space per capita [19].

2. Literature Review

2.1. Urban Open Spaces

2.2. Spatial Analysis of Urban Open Spaces

- Urban green space is unevenly distributed globally, with the highest in Europe and the lowest in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

- European and North American cities have significantly more green land cover than African and Asian cities.

- Green space declines with higher population density, especially beyond 300–400 people per 250 × 250 m.

- Climate is the dominant driver, explaining ~75% of variation in green space; precipitation is especially influential, with greener cities in cooler, wetter climates.

- Human factors, such as development status and population density, also significantly affect urban green space.

- UN-Habitat studies have demonstrated that the amount of land allocated to public spaces in developing countries is limited.

2.3. The X-Minute City Concept

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Case Study Area

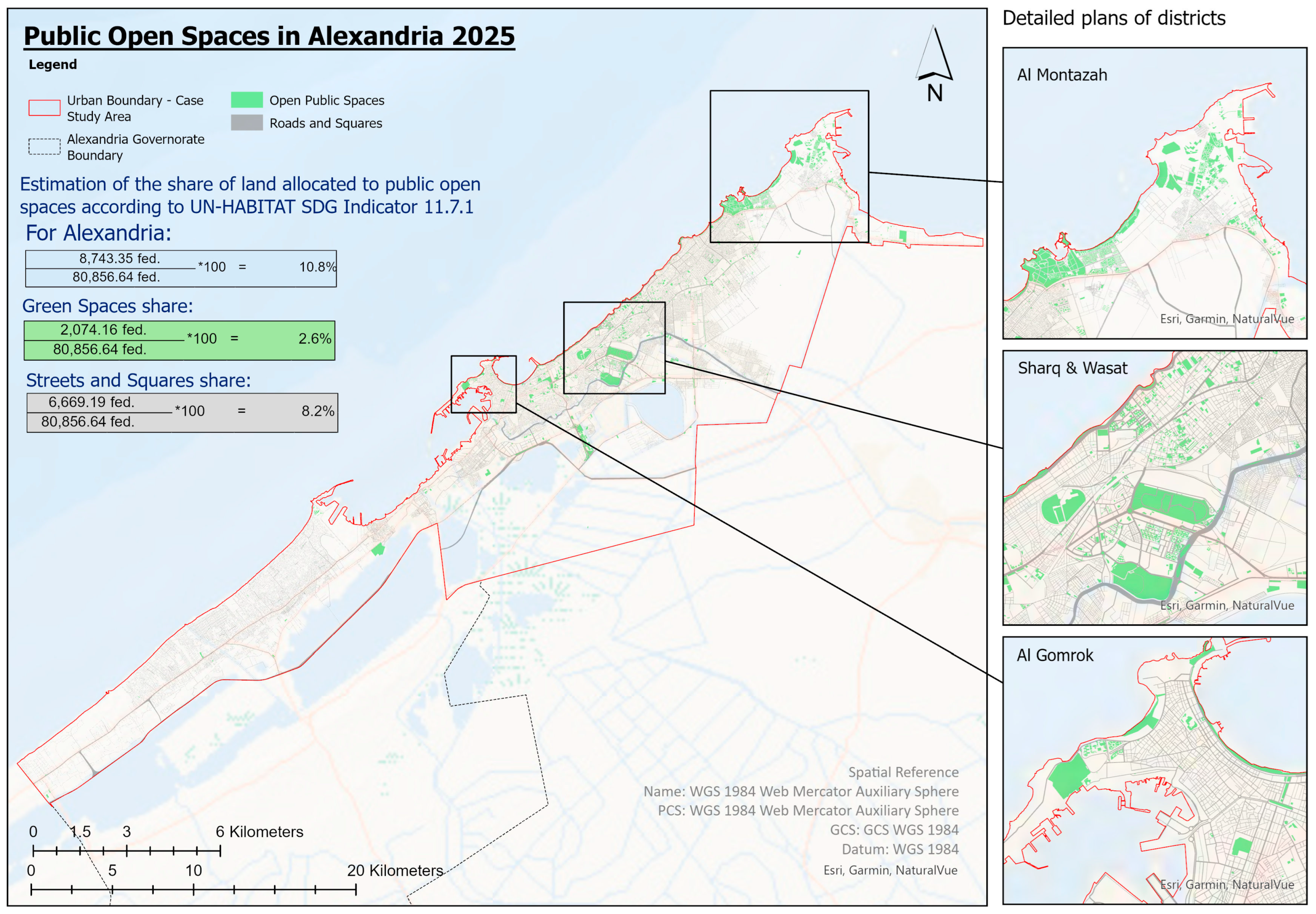

4.2. Land Allocation Calculations

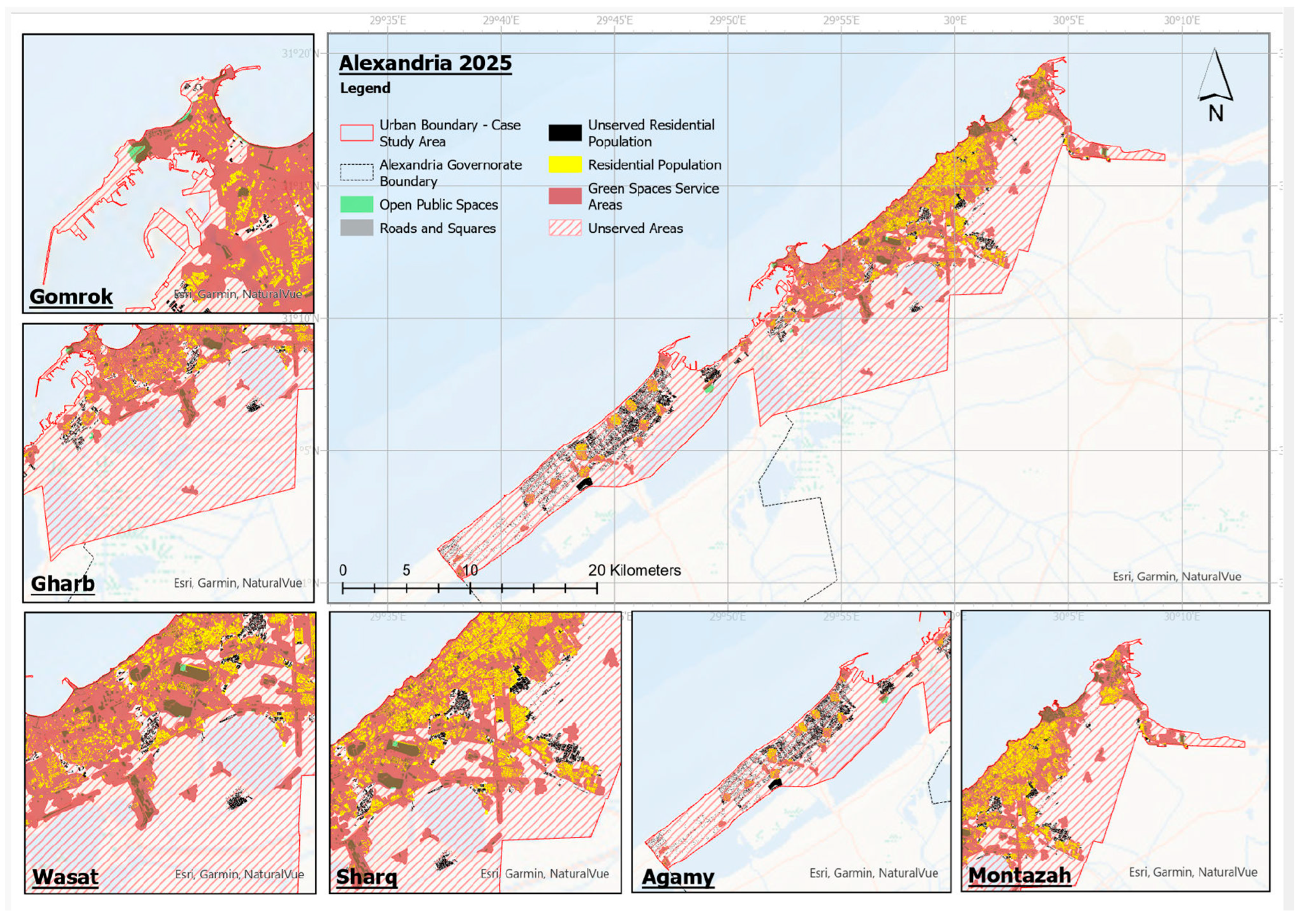

4.3. Access to Green Spaces

- The districts of Agamy and Gharb show the most critical lack of coverage. Agamy, the largest district, has a massive 91.82% unserved rate, while Gharb closely follows with 91.20% unserved. This illustrates that these western areas are overwhelmingly dominated by the “Unserved Areas” designation, suggesting that residents in these districts experience significant environmental injustice regarding proximity to public green infrastructure.

- Conversely, Al Gomrok, the smallest district in the city core, shows the highest relative accessibility, with an unserved rate of only 34.35%. The smaller size and dense, central network of streets contribute to this comparatively higher coverage.

- Sharq, Al Montazah, and Wasat Districts represent intermediate accessibility levels, with unserved rates ranging from 52.08% to 59.34%. While performing better than the peripheral districts, these figures still indicate that more than half of the urban area in these zones lacks convenient walking access to green spaces, underscoring persistent accessibility challenges even in more centrally located regions.

4.4. Analysis and Reporting

5. Discussion

5.1. Deficit in Quantitative Provision

5.2. Spatial Inequality in Accessibility

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vazquez, S.A.; Ostermann, F.O.; Madureira, A.M.P.S.; Pfeffer, K. Using a digital participatory platform to evaluate public space quality. GeoJournal 2025, 90, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addas, A.; Alserayhi, G. Quantitative evaluation of public open space per inhabitant in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A case study of the city of Jeddah. Sage Open 2020, 10, 2158244020920608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachar, S. Exploring the Future of Public Spaces in Urban Design. Space 2025, 1, 2. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. SDG Indicator 11.7.1 Training Module: Public Space; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- As+P. General Strategic Master Plan Alexandria 2032. 2025. Available online: https://www.as-p.com/projects/general-strategic-master-plan-alexandria-2032-184 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Perdue, W.C.; Stone, L.A.; Gostin, L.O. The built environment and its relationship to the public’s health: The legal framework. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1390–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sclar, E.; Volavka-Close, N. Urban health: An overview. Encycl. Environ. Health 2011, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harpham, T. Urban health in developing countries: What do we know and where do we go? Health Place 2009, 15, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Xia, J.; Wu, D. Ecological Resilience and Urban Health: A Global Analysis of Research Hotspots and Trends in Nature-Based Solutions. Forests 2025, 16, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colglazier, W. Sustainable development agenda: 2030. Science 2015, 349, 1048–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, E. Introduction: The 2030 agenda. J. Glob. Ethics 2015, 11, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineo, H.; Zimmermann, N.; Davies, M. Integrating health into the complex urban planning policy and decision-making context: A systems thinking analysis. Palgrave Commun. 2020, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naya, R.B.; de la Cal Nicolás, P.; Medina, C.D.; Ezquerra, I.; García-Pérez, S.; Monclús, J. Quality of public space and sustainable development goals: Analysis of nine urban projects in Spanish cities. Front. Archit. Res. 2023, 12, 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.E.; Handley, J.F.; Ennos, A.R.; Pauleit, S. Adapting cities for climate change: The role of the green infrastructure. Built. Environ. 2007, 33, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkoy, S.; Şahin, M.; Avşar, E. Evaluation of urban green area development in the context of sustainable eco-city perspective: Bilecik (city center) case study. Braz. J. Sci. 2025, 4, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bille, R.A.; Jensen, K.E.; Buitenwerf, R. Global patterns in urban green space are strongly linked to human development and population density. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 86, 127980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, F.R.; Izidro, G.; da Silva, M.S.R.; Pezzuto, C.C.; Longo, R.M. Environmental assessment of green areas in the city of Campinas, SP: A study of sustainability and biodiversity. Rev. Gestão Soc. Ambient. 2024, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Yang, D.; Niu, X.; Mi, Z. The Impact of Park Green Space Areas on Urban Vitality: A Case Study of 35 Large and Medium-Sized Cities in China. Land 2024, 13, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şenik, B.; Uzun, O. A process approach to the open green space system planning. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2022, 18, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ge, Y.; Yang, G.; Wu, Z.; Du, Y.; Mao, F.; Liu, S.; Xu, R.; Qu, Z.; Xu, B. Inequalities of urban green space area and ecosystem services along urban center-edge gradients. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 217, 104266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khor, N.J.K. World Cities Report 2022: Envisaging the Future of Cities; United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat): Nairobi, Kenya, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Schindler, M.; Le Texier, M.; Caruso, G. How far do people travel to use urban green space? A comparison of three European cities. Appl. Geogr. 2022, 141, 102673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citaristi, I. United nations human settlements programme—UN-habitat. In The Europa Directory of International Organizations 2022; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 240–243. [Google Scholar]

- Habitat, U. Healthier Cities and Communities Through Public Spaces; UN Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, C.; Ståhle, A.; Spacescape, C.; Kamiya, M.; Aguinaga, G.; Siegel, Y. Developing Public Space and Land Values in Cities and Neighbourhoods; UN Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Badiu, D.L.; Iojă, C.I.; Pătroescu, M.; Breuste, J.; Artmann, M.; Niță, M.R.; Grădinaru, S.R.; Hossu, C.A.; Onose, D.A. Is urban green space per capita a valuable target to achieve cities’ sustainability goals? Romania as a case study. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 70, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.M. Revisiting planning standards for open spaces in urban areas from global and national perspectives. J. Bangladesh Inst. Plan. 2019, 12, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, R. Quantitative evaluation of distribution and accessibility of urban green spaces (Case study: City of Jeddah). Int. J. Geomat. Geosci. 2014, 4, 526–535. [Google Scholar]

- Sangwan, A.; Saraswat, A.; Kumar, N.; Pipralia, S.; Kumar, A. Urban green spaces prospects and retrospect’s. In Urban Green Spaces; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gameel, J.E.; Nour, W.A.; Abouisaadat, A. Monitoring and Documenting Local Legislation Role in Urban Governance to Keep Green Areas in New Cities. J. Eng. Res. 2025, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, A.; Mutai, J. City-Wide Public Space Strategies: A Compendium of Inspiring Practices; United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat): Nairobi, Kenya, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Habitat, U. City-Wide Public Space Strategies: A Guidebook for City Leaders. 2020. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/city-wide-public-space-strategies-a-guidebook-for-city-leaders (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Cerin, E.; Conway, T.L.; Adams, M.A.; Frank, L.D.; Pratt, M.; Salvo, D.; Schipperijn, J.; Smith, G.; Cain, K.L. Physical activity in relation to urban environments in 14 cities worldwide: A cross-sectional study. Lancet 2016, 387, 2207–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.J.; Crane, D.E.; Stevens, J.C. Air pollution removal by urban trees and shrubs in the United States. Urban For. Urban Green. 2006, 4, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouhassan, M.; Anwar, R.; Elkhateeb, S. Humanizing Public Open Spaces in Jeddah: The Case of Prince Majid Park. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla, D.G.; Capin, T.; Cabatingan, R.M.; Lacson, D.R.Y.; Lauro, E.K.; Lima, K.A. Urban green spaces and human wellbeing: Assessing the carrying capacity of urban parks and recreation areas in danao city. Int. J. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 9, 30–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cimini, A.; De Fioravante, P.; Marinosci, I.; Congedo, L.; Cipriano, P.; Dazzi, L.; Marchetti, M.; Scarascia Mugnozza, G.; Munafò, M. Green Urban Public Spaces Accessibility: A Spatial Analysis for the Urban Area of the 14 Italian Metropolitan Cities Based on SDG Methodology. Land 2024, 13, 2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Planning and Economic Development. The National Agenda for Sustainable Development. In Egypt’s Updated Vision 2030; Ministry of Planning and Economic Development: Cairo, Egypt, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ramadhan, A.K.; Saputra, E. Green open space planning based on spatial justice in Jakarta: Study of child friendly integrated public spaces/RPTRA and general green open space. J. Placemak. Streetscape Des. 2025, 2, 100–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aweh, M.A.; Sana, D.; Atchrimi, T. Accessibility and Inclusiveness of Public Open Spaces in Fragile Contexts: A Case Study of Kaya, Burkina Faso. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ma, X.; Hu, Z.; Li, S. Investigation of urban green space equity at the city level and relevant strategies for improving the provisioning in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almadina, A.; Marcillia, S. Discover inclusivity of open public spaces in gen z perspective, case study: Alun-Alun Kidul Yogyakarta. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, M.G.; Elboshy, B.; Mahmod, W.E. Integrated approach to assess the urban green infrastructure priorities (Alexandria, Egypt). In Advances in Sustainable and Environmental Hydrology, Hydrogeology, Hydrochemistry and Water Resources; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Gawad, E.; Ayad, H.M.; Saadallah, D. Delineating and Assessing Urban Green Infrastructure in Cities: Application of the Patch Matrix Model in Alexandria, Egypt. In Mobility, Knowledge and Innovation Hubs in Urban and Regional Development, Proceedings of REAL CORP 2022, 27th International Conference on Urban Development, Regional Planning and Information Society, Vienna, Austria, 14–16 November 2022; CORP–Competence Center of Urban and Regional Planning: Graz, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Abd-Rabp, L.; Abdelall, M.; El Sayad, Z. Impact of Urban Attributes on Human Happiness and Health in Alexandria as an Egyptian City. In Let it Grow, Let us Plan, Let it Grow, Nature-Based Solutions for Sustainable Resilient Smart Green and Blue Cities, Proceedings of REAL CORP 2023, 28th International Conference on Urban Development, Regional Planning and Information Society, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 18–20 September 2023; CORP–Competence Center of Urban and Regional Planning: Graz, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nasr, M.; Ali, S.; Mohamed, A. Adapting Restorative Urban Design, for Open Spaces Towards, Thermal Heat Island, Reaching Human Mental Health and Well-Being, Case Study: Qaitbay Citadel Plaza, Alexandria, Egypt. Future Cities Environ. 2025, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R.; Sharifi, A.; Sadeghi, A. The 15-minute city: Urban planning and design efforts toward creating sustainable neighborhoods. Cities 2023, 132, 104101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.; Nazir, H.; Qazi, A.W. Exploring the 15-Minutes City Concept: Global Challenges and Opportunities in Diverse Urban Contexts. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepehri, B.; Sharifi, A. X-minute cities as a growing notion of sustainable urbanism: A literature review. Cities 2025, 161, 105902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozoukidou, G.; Chatziyiannaki, Z. 15-Minute City: Decomposing the New Urban Planning Eutopia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, E.; Lu, M. 15-Minute City. In International Encyclopedia of Geography: People, the Earth, Environment and Technology; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, R.; Higgs, C.; Heikinheimo, V.; Hunter, R.; Vargas, J.C.B.; Liu, S.; Resendiz, E.; Boeing, G.; Adlakha, D.; Schifanella, R. Internationally Validated Open Access Indicators of Large Public Urban Green Space for Healthy and Sustainable Cities. Geogr. Anal. 2025, 57, 793–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandria Green City Action Plan. 2025. Available online: https://www.ebrdgreencities.com/assets/Alexandria-Green-City-Action-Plan-english.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Alexandria Population. 2025. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/cities/egypt/alexandria (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Illarionova, O.A.; Klimanova, O.A.; Grechman, E.V. Urban Green Infrastructure of Russian South: Spatial Justice-Ecological Efficiency Nexus. Geogr. Environ. Sustain. 2025, 18, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.J. Assessing Urban Forest Effects and Values: Washington, DC’s Urban Forest; United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research: Madison, WI, USA, 2006; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

| Type of Spaces | Share per Person (Mid 2025 CAPMAS Population = 5,630,000) | Share per Person (Near Future Estimation Population = 6,000,000) | Does it Meet International Standards? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| m2 | m2 | UN | WHO | |

| Total Open Spaces | 6.51 | 6.11 | No | No |

| Green Spaces | 1.55 | 1.45 | No | No |

| Streets and Squares | 4.96 | 4.66 | No | No |

| Type of Spaces | Area | Percentages from the Total Urban Boundary (Share) |

|---|---|---|

| m2 | ||

| Total Open Spaces | 36,622,900 | 10.8% |

| Green Spaces | 8,710,440 | 2.6% |

| Streets and Squares | 27,931,680 | 8.2% |

| Total area of Urban Boundary | 339,593,088 |

| District/Area of Focus | District Area (M2) | Green Spaces Area (M2) | Service Area of Green Spaces (M2) | Unserved Urban Area (M2) | % of Unserved Areas |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agamy | 95,651,555.68 | 477,518.12 | 7,824,902.42 | 87,826,653.26 | 91.82% |

| Al Montazah | 84,941,787.49 | 3,428,331.49 | 34,917,966.20 | 50,023,821.29 | 58.89% |

| Al Gomrok | 4,678,268.62 | 129,955.49 | 3,071,463.46 | 1,606,805.16 | 34.35% |

| Sharq | 50,870,476.53 | 2,618,459.62 | 24,379,545.32 | 26,490,931.21 | 52.08% |

| Wasat | 29,596,274.88 | 1,082,181.29 | 12,034,489.95 | 17,561,784.94 | 59.34% |

| Gharb | 73,863,121.13 | 198,180.68 | 6,501,909.84 | 67,361,211.29 | 91.20% |

| Case Study Area Boundary | 339,601,484.32 | 8,711,483.20 | 88,730,277.19 | 250,871,207.14 | 73.87% |

| As For Effect on Residential Populations | Total Area (m2) | Areas That Can Access Green Spaces in 5 min (m2) | Areas Outside of the Service Areas (m2) | % Of Unserved Areas per District |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residential Buildings in Case Study Area | 42,714,196.96 | 24,724,177.19 | 17,990,019.77 | 42.12% |

| Agamy | 15,545,956.21 | 2,410,388.78 | 13,135,567.44 | 84.50% |

| Al Montazah | 14,859,096.99 | 12,706,937.41 | 2,152,159.59 | 14.48% |

| Al Gomrok | 451,630.15 | 387,438.95 | 64,191.20 | 14.21% |

| Sharq | 7,676,566.65 | 6,591,813.97 | 1,084,752.68 | 14.13% |

| Wasat | 2,386,138.25 | 1,619,894.62 | 766,243.63 | 32.11% |

| Gharb | 1,742,997.19 | 955,891.94 | 787,105.24 | 45.16% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Saadallah, D.M.; Othman, E.M. Promoting Healthier Cities and Communities Through Quantitative Evaluation of Public Open Space per Inhabitant. Urban Sci. 2026, 10, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10010011

Saadallah DM, Othman EM. Promoting Healthier Cities and Communities Through Quantitative Evaluation of Public Open Space per Inhabitant. Urban Science. 2026; 10(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaadallah, Dina M., and Esraa M. Othman. 2026. "Promoting Healthier Cities and Communities Through Quantitative Evaluation of Public Open Space per Inhabitant" Urban Science 10, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10010011

APA StyleSaadallah, D. M., & Othman, E. M. (2026). Promoting Healthier Cities and Communities Through Quantitative Evaluation of Public Open Space per Inhabitant. Urban Science, 10(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10010011