Self-Sampling Modality for Cervical Cancer Screening: Overview of the Diagnostic Approaches and Sampling Devices

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- To describe the diagnostic accuracy of HPV self-sampling kits/devices regarding their sensitivity and specificity;

- (2)

- Assess patients’ acceptance, preference for various devices, and experiences of women about self-sampling for HPV testing;

- (3)

- To identify barriers and facilitators that influence the implementation of the self-sampling modality for cervical cancer screening.

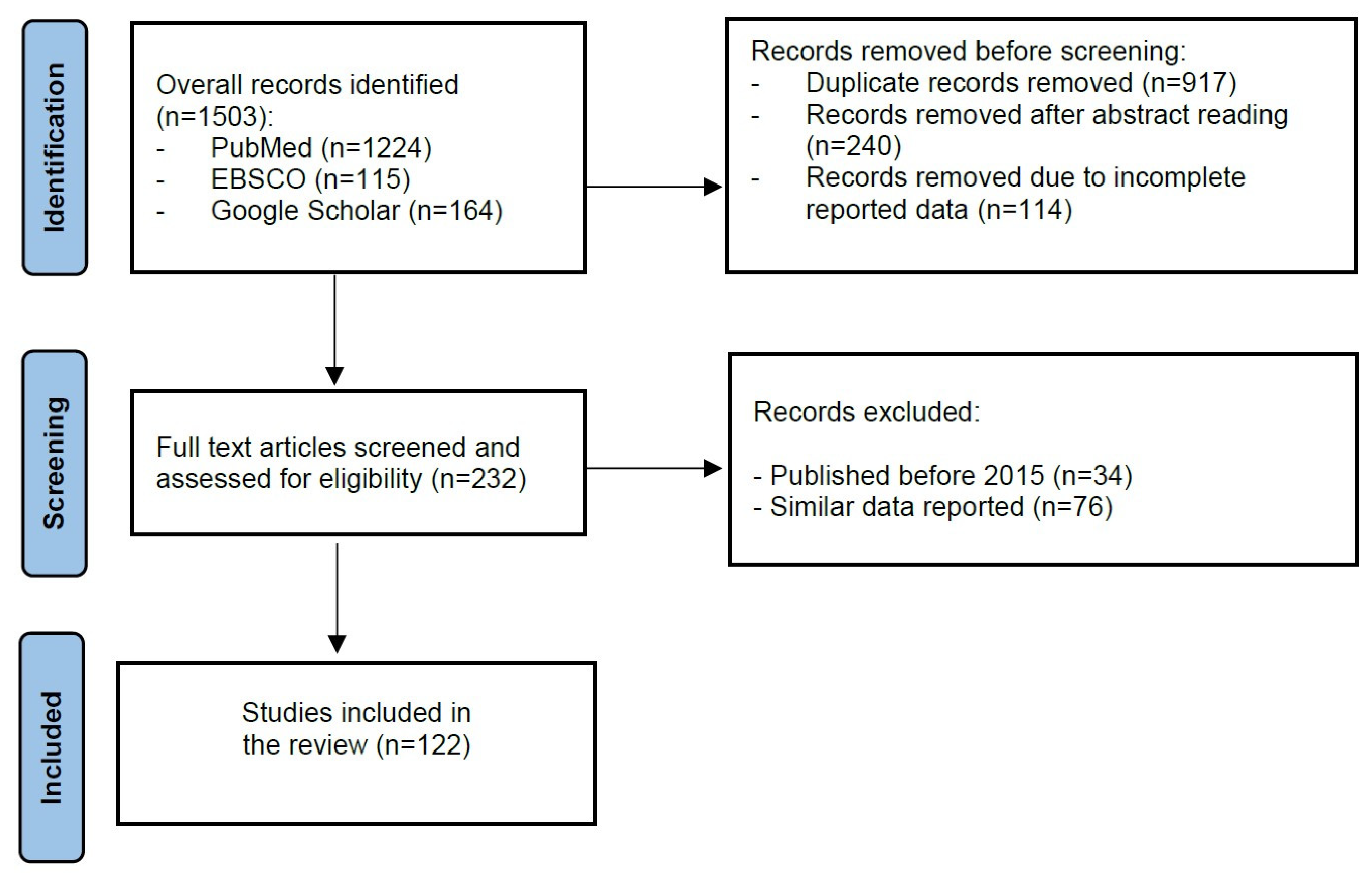

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Self-Sampling Approaches for Cervical Cancer Screening

3.1.1. Vaginal Self-Sampling

3.1.2. Urine Self-Sampling

3.2. Self-Sampling Devices/Kits Used for Cervical Cancer Screening

3.3. Laboratory Tests for HPV Identification from Self-Collected Samples

3.4. Patients’ Acceptance of Self-Sampling Modality

3.5. Comparison of the Self-Sampling Approach Efficacy in Urban and Rural Areas

3.6. Barriers and Facilitators for Self-Sampling

3.7. Cost-Effectiveness of Self-Sampling Modality for Cervical Cancer Screening

3.8. Self-Sampling Modality Strengths and Limitations

- (1)

- Self-sampling allows the sample collection to be completed in a short period without heavy input from medical workers, making positive patient management more centralized and efficient, lowering the screening cost significantly;

- (2)

- Through the binding set between the treatment and recheck of positive patients, a closed-loop process is established for cervical cancer prevention, ensuring standard diagnostics and treatment for positive patients and meanwhile, maximizing their treatment rate;

- (3)

- Local staff receive training in the management process of positive patients, allowing them to undertake positive patient management and long-term follow-up; meanwhile, by focusing on positive patients’ management, they can improve their skills in diagnostics and treatment in a short period;

- (4)

- Cervical cancer screening is carried out at the basic level, improving the capability of basic medical units in cervical cancer prevention and constructing a sustainable cervical cancer prevention system.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, M.; Cao, C.; Wu, P.; Huang, X.; Ma, D. Advances in cervical cancer: Current insights and future directions. Cancer Commun. 2025, 45, 77–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, Z.; Liu, P.; Yin, A.; Zhang, B.; Xu, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Tang, L.; et al. Global landscape of cervical cancer incidence and mortality in 2022 and predictions to 2030: The urgent need to address inequalities in cervical cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2025, 157, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO GLOBOCAN. Cancer Tomorrow. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow/en/dataviz/isotype?types=0&single_unit=5000&populations=900&group_populations=0&multiple_populations=0&years=2025&cancers=23 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- GBD 2023 Demographics Collaborators. Global age-sex-specific all-cause mortality and life expectancy estimates for 204 countries and territories and 660 subnational locations, 1950–2023: A demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. Lancet 2025, 406, 1731–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2023 Cancer Collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of cancer, 1990-2023, with forecasts to 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. Lancet 2025, 406, 1565–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ukybassova, T.; Aimagambetova, G.; Kongrtay, K.; Kassymbek, K.; Terzic, M.; Makhambetova, S.; Galym, M.; Kamzayeva, N. Correlation of HPV Status with Colposcopy and Cervical Biopsy Results Among Non-Vaccinated Women: Findings from a Tertiary Care Hospital in Kazakhstan. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhatova, A.; Azizan, A.; Atageldiyeva, K.; Ashimkhanova, A.; Marat, A.; Iztleuov, Y.; Suleimenova, A.; Shamkeeva, S.; Aimagambetova, G. Prophylactic Human Papillomavirus Vaccination: From the Origin to the Current State. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arbyn, M.; Weiderpass, E.; Bruni, L.; de Sanjosé, S.; Saraiya, M.; Ferlay, J.; Bray, F. Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: A worldwide analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e191–e203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.K.; Aimagambetova, G.; Ukybassova, T.; Kongrtay, K.; Azizan, A. Human Papillomavirus Infection and Cervical Cancer: Epidemiology, Screening, and Vaccination-Review of Current Perspectives. J. Oncol. 2019, 2019, 3257939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canfell, K. Towards the global elimination of cervical cancer. Papillomavirus Res. 2019, 8, 100170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Das, M. WHO launches strategy to accelerate elimination of cervical cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 20–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, D.; Vignat, J.; Lorenzoni, V.; Eslahi, M.; Ginsburg, O.; Lauby-Secretan, B.; Arbyn, M.; Basu, P.; Bray, F.; Vaccarella, S. Global estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2020: A baseline analysis of the WHO Global Cervical Cancer Elimination Initiative. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, e197–e206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Issa, T.; Babi, A.; Azizan, A.; Alibekova, R.; Khan, S.A.; Issanov, A.; Chan, C.K.; Aimagambetova, G. Factors associated with cervical cancer screening behaviour of women attending gynaecological clinics in Kazakhstan: A cross-sectional study. Womens Health 2021, 17, 17455065211004135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aimagambetova, G.; Atageldiyeva, K.; Marat, A.; Suleimenova, A.; Issa, T.; Raman, S.; Huang, T.; Ashimkhanova, A.; Aron, S.; Dongo, A.; et al. Comparison of diagnostic accuracy and acceptability of self-sampling devices for human Papillomavirus detection: A systematic review. Prev. Med. Rep. 2024, 38, 102590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rajaram, S.; Gupta, B. Screening for cervical cancer: Choices & dilemmas. Indian J. Med. Res. 2021, 154, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rerucha, C.M.; Caro, R.J.; Wheeler, V.L. Cervical Cancer Screening. Am. Fam. Physician 2018, 97, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, A.E.; Feldman, S. Update on primary HPV screening for cervical cancer prevention. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2018, 42, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najib, F.S.; Hashemi, M.; Shiravani, Z.; Poordast, T.; Sharifi, S.; Askary, E. Diagnostic Accuracy of Cervical Pap Smear and Colposcopy in Detecting Premalignant and Malignant Lesions of Cervix. Indian, J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 11, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- National Cancer Institute. Cervical Cancer Screening—Patient Version. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/types/cervical/patient/cervical-screening-pdq (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- World Health Organization. Screening and Treatment of Cervical Pre-Cancer Lesions. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer#:∼:text=Screening%20should%20start%20from%2030,every%203%20to%205%20years (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Winer, R.L.; Lin, J.; Anderson, M.L.; Tiro, J.A.; Green, B.B.; Gao, H.; Meenan, R.T.; Hansen, K.; Sparks, A.; Buist, D.S.M. Strategies to Increase Cervical Cancer Screening With Mailed Human Papillomavirus Self-Sampling Kits: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2023, 330, 1971–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Johnson, L.G.; Saidu, R.; Mbulawa, Z.; Williamson, A.; Boa, R.; Tergas, A.; Moodley, J.; Persing, D.; Campbell, S.; Tsai, W.; et al. Selecting human papillomavirus genotypes to optimize the performance of screening tests among South African women. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 6813–6824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, E.H.; Park, M.S.; Woo, H.Y.; Park, H.; Kwon, M.J. Evaluation of clinical usefulness of HPV-16 and HPV-18 genotyping for cervical cancer screening. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2024, 35, e72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Cancer-Preventive Interventions. Cervical Cancer Screening. Lyon (FR): International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2022. Available online: https://www.iarc.who.int/news-events/publication-of-iarc-handbooks-of-cancer-prevention-volume-18-cervical-cancer-screening/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Bruni, L.; Serrano, B.; Roura, E.; Alemany, L.; Cowan, M.; Herrero, R.; Poljak, M.; Murillo, R.; Broutet, N.; Riley, L.M.; et al. Cervical cancer screening programmes and age-specific coverage estimates for 202 countries and territories worldwide: A review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e1115–e1127, Erratum in Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, e1011. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00240-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fuzzell, L.N.; Perkins, R.B.; Christy, S.M.; Lake, P.W.; Vadaparampil, S.T. Cervical cancer screening in the United States: Challenges and potential solutions for underscreened groups. Prev. Med. 2021, 144, 106400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervical Screening in Australia 2014–2015. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer-screening/cervical-screening-in-australia-2014-2015/summary (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- OECD. Health for Everyone? Social Inequalities in Health and Health Systems; OECD Health Policy Studies; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemp, J.M.; De Neve, J.W.; Bussmann, H.; Chen, S.; Manne-Goehler, J.; Theilmann, M.; Marcus, M.E.; Ebert, C.; Probst, C.; Tsabedze-Sibanyoni, L.; et al. Lifetime Prevalence of Cervical Cancer Screening in 55 Low- and Middle-Income Countries. JAMA 2020, 324, 1532–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abila, D.B.; Wasukira, S.B.; Ainembabazi, P.; Kiyingi, E.N.; Chemutai, B.; Kyagulanyi, E.; Varsani, J.; Shindodi, B.; Kisuza, R.K.; Niyonzima, N. Coverage and Socioeconomic Inequalities in Cervical Cancer Screening in Low- and Middle-Income Countries Between 2010 and 2019. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2024, 10, e2300385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, B.; Ibáñez, R.; Robles, C.; Peremiquel-Trillas, P.; de Sanjosé, S.; Bruni, L. Worldwide use of HPV self-sampling for cervical cancer screening. Prev. Med. 2022, 154, 106900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerstl, S.; Lee, L.; Nesbitt, R.C.; Mambula, C.; Sugianto, H.; Phiri, T.; Kachingwe, J.; Llosa, A.E. Cervical cancer screening coverage and its related knowledge in southern Malawi. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- De Pauw, H.; Donders, G.; Weyers, S.; De Sutter, P.; Doyen, J.; Tjalma, W.A.A.; Vanden Broeck, D.; Peeters, E.; Van Keer, S.; Vorsters, A.; et al. Cervical cancer screening using HPV tests on self-samples: Attitudes and preferences of women participating in the VALHUDES study. Arch. Public Health 2021, 79, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Narvaez, L.; Viviano, M.; Dickson, C.; Jeannot, E. The acceptability of HPV vaginal self-sampling for cervical cancer screening in Latin America: A systematic review. Public Health Pract. 2023, 6, 100417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nishimura, H.; Yeh, P.T.; Oguntade, H.; Kennedy, C.E.; Narasimhan, M. HPV self-sampling for cervical cancer screening: A systematic review of values and preferences. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e003743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arbyn, M.; Simon, M.; de Sanjosé, S.; Clarke, M.A.; Poljak, M.; Rezhake, R.; Berkhof, J.; Nyaga, V.; Gultekin, M.; Canfell, K.; et al. Accuracy and effectiveness of HPV mRNA testing in cervical cancer screening: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 950–960, Erratum in Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, e370. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00388-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, S.; Verberckmoes, B.; Castle, P.E.; Arbyn, M. Offering HPV self-sampling kits: An updated meta-analysis of the effectiveness of strategies to increase participation in cervical cancer screening. Br. J. Cancer 2023, 128, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Amir, S.M.; Idris, I.B.; Mohd Yusoff, H. The Acceptance of Human Papillomavirus Self-Sampling Test among Muslim Women:A Systematic Review. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2022, 23, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arbyn, M.; Smith, S.B.; Temin, S.; Sultana, F.; Castle, P. Collaboration on Self-Sampling HPVTesting. Detecting cervical precancer reaching underscreened women by using HPVtesting on self samples: Updated meta-analyses. BMJ 2018, 363, k4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cadman, L.; Reuter, C.; Jitlal, M.; Kleeman, M.; Austin, J.; Hollingworth, T.; Parberry, A.L.; Ashdown-Barr, L.; Patel, D.; Nedjai, B.; et al. A Randomized Comparison of Different Vaginal Self-sampling Devices and Urine for Human Papillomavirus Testing-Predictors 5.1. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2021, 30, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ertik, F.C.; Kampers, J.; Hülse, F.; Stolte, C.; Böhmer, G.; Hillemanns, P.; Jentschke, M. CoCoss-Trial: Concurrent Comparison of Self-Sampling Devices for HPV-Detection. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang, C.Y.; Chang, T.C.; Chou, H.H.; Chao, A.; Hsu, S.T.; Shih, Y.H.; Huang, H.J.; Lin, C.T.; Chen, M.Y.; Sun, L.; et al. Evaluation of a novel vaginal cells self-sampling device for human papillomavirus testing in cervical cancer screening: A clinical trial assessing reliability and acceptability. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2024, 9, e10653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Borgfeldt, C.; Forslund, O. Increased HPV detection by the use of a pre-heating step on vaginal self-samples analysed by Aptima HPV assay. J. Virol. Methods 2019, 270, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asciutto, K.C.; Ernstson, A.; Forslund, O.; Borgfeldt, C. Self-sampling with HPV mRNA analyses from vagina and urine compared with cervical samples. J. Clin. Virol. 2018, 101, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asciutto, K.C.; Henningsson, A.J.; Borgfeldt, H.; Darlin, L.; Borgfeldt, C. Vaginal and Urine Self-sampling Compared to Cervical Sampling for HPV-testing with the Cobas 4800 HPV Test. Anticancer Res. 2017, 37, 4183–4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuriakose, S.; Sabeena, S.; Damodaran, B.; Ravishankar, N.; Ramachandran, A.; Ameen, N. Comparison of two self-sampling methods for human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA testing among women with high prevalence rates. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 3884–3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burroni, E.; Bonanni, P.; Sani, C.; Lastrucci, V.; Carozzi, F.; The HPV ScreeVacc Working Group; Iossa, A.; Andersson, K.L.; Brandigi, L.; Di Pierro, C.; et al. Human papillomavirus prevalence in paired urine and cervical samples in women invited for cervical cancer screening. J. Med. Virol. 2015, 87, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyabigambo, A.; Mayega, R.W.; Mendoza, H.; Shiraz, A.; Doorbar, J.; Atuyambe, L.; Ginindza, T.G. The preference of women living with HIV for the HPV self-sampling of urine at a rural HIV clinic in Uganda. S Afr. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 37, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arbyn, M.; Peeters, E.; Benoy, I.; Vanden Broeck, D.; Bogers, J.; De Sutter, P.; Donders, G.; Tjalma, W.; Weyers, S.; Cuschieri, K.; et al. Valhudes: A protocol for validation of human papillomavirus assays and collection devices for HPV testing on self-samples and urine samples. J. Clin. Virol. 2018, 107, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, E.F.; Andrus, E.C.; Sandler, C.B.; Moravek, M.B.; Stroumsa, D.; Kattari, S.K.; Walline, H.M.; Goudsmit, C.M.; Brouwer, A.F. Cervicovaginal and anal self-sampling for HPV testing in a transgender and gender diverse population assigned female at birth: Comfort, difficulty, and willingness to use. LGBT Health 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avaniss-Aghajani, E.; Sarkissian, A.; Fernando, F.; Avaniss-Aghajani, A. Validation of the Hologic Aptima Unisex and Multitest Specimen Collection Kits Used for Endocervical and Male Urethral Swab Specimens (Aptima Swabs) for Collection of Samples from SARS-CoV-2-Infected Patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58, e00753-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ploysawang, P.; Pitakkarnkul, S.; Kolaka, W.; Ratanasrithong, P.; Khomphaiboonkij, U.; Tipmed, C.; Seeda, K.; Pangmuang, P.; Sangrajrang, S. Acceptability preference for human papilloma virus self-sampling among thai women attending national cancer institute. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2023, 24, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ngu, S.F.; Lau, L.S.; Chan, C.Y.; Ngan, H.Y.; Cheung, A.N.; Chan, K.K. Acceptability of self-collected vaginal samples for human papillomavirus testing for primary cervical cancer screening: Comparison of face-to-face and online recruitment modes. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chan, A.H.Y.; Ngu, S.F.; Lau, L.S.K.; Tsun, O.K.L.; Ngan, H.Y.S.; Cheung, A.N.Y.; Chan, K.K.L. Evaluation of an isothermal amplification HPV assay on self-collected vaginal samples as compared to clinician-collected cervical samples. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, E.; Katz, M.L.; Reiter, P.L. Acceptability of human papillomavirus self-sampling among a national sample of women in the United States. BioRes. Open Access 2019, 8, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranberg, M.; Van Keer, S.; Jensen, J.S.; Nørgaard, P.; Gustafson, L.W.; Hammer, A.; Bor, P.; Binderup, K.O.; Blach, C.; Vorsters, A. High-risk human papillomavirus testing in first-void urine as a novel and non-invasive cervical cancer screening modality-a Danish diagnostic test accuracy study. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibert, M.J.; Sánchez-Contador, C.; Artigues, G. Validity and acceptance of self vs. conventional sampling for the analysis of human papillomavirus and Pap smear. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 2809, Erratum in Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10881. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-37880-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Inturrisi, F.; Aitken, C.A.; Melchers, W.J.G.; van den Brule, A.J.C.; Molijn, A.; Hinrichs, J.W.J.; Niesters, H.G.M.; Siebers, A.G.; Schuurman, R.; Heideman, D.A.M.; et al. Clinical performance of high-risk HPV testing on self-samples versus clinician samples in routine primary HPV screening in the Netherlands: An observational study. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2021, 11, 100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Martinelli, M.; Giubbi, C.; Di Meo, M.L.; Perdoni, F.; Musumeci, R.; Leone, B.E.; Fruscio, R.; Landoni, F.; Cocuzza, C.E. Accuracy of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Testing on Urine and Vaginal Self-Samples Compared to Clinician-Collected Cervical Sample in Women Referred to Colposcopy. Viruses 2023, 15, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Crofts, V.; Flahault, E.; Tebeu, P.M.; Untiet, S.; Boulvain, M.; Vassilakos, P.; Petignat, P.; Flore, G.K.-F.G. Education efforts may contribute to wider acceptance of human papillomavirus self-sampling. Int. J. Womens Health 2015, 7, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manley, K.M.; Wills, A.K.; Villeneuve, N.; Hunt, K.; Patel, A.; Glew, S. Comparison of the Cervex-Brush alone to Cytobrush plus Cervex-Brush for detection of cervical dysplasia in women with a transformation zone type 3. Cytopathology 2019, 30, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winer, R.L.; Gonzales, A.A.; Noonan, C.J.; Cherne, S.L.; Buchwald, D.S. Collaborative to improve native cancer outcomes (CINCO) assessing acceptability of self-sampling kits prevalence risk factors for human papillomavirus infection in American Indian Women. J. Community Health 2016, 41, 1049–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Klug, A.C.; Saumoy, M.; Baixeras, N.; Trenti, L.; Catala, I.; Vidal, A.; Torres, M.; Alemany, L.; Videla, S.; Jose, S.D.S.; et al. Comparison of two sample collection devices for anal cytology in HIV-positive men who have sex with men: Cytology brush and Dacron swab. Cytopathology 2021, 32, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enerly, E.; Bonde, J.; Schee, K.; Pedersen, H.; Lönnberg, S.; Nygård, M. Self-Sampling for Human Papillomavirus Testing among Non-Attenders Increases Attendance to the Norwegian Cervical Cancer Screening Programme. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shih, Y.H.; Sun, L.; Hsu, S.T.; Chen, M.J.; Lu, C.H. Can HPVtest on random urine replace self-HPVtest on vaginal self-samples or clinician-collected cervical samples? Int. J. Womens Health 2023, 11, 1421–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Latsuzbaia, A.; Van Keer, S.; Vanden Broeck, D.; Weyers, S.; Donders, G.; De Sutter, P.; Tjalma, W.; Doyen, J.; Vorsters, A.; Arbyn, M. Clinical Accuracy of Alinity m HR HPV Assay on Self- versus Clinician-Taken Samples Using the VALHUDES Protocol. J. Mol. Diagn. 2023, 25, 957–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latsuzbaia, A.; Martinelli, M.; Giubbi, C.; Cuschieri, K.; Elasifer, H.; Iacobone, A.D.; Bottari, F.; Piana, A.F.; Pietri, R.; Tisi, G.; et al. Clinical accuracy of OncoPredict HPV Quantitative Typing (QT) assay on self-samples. J. Clin. Virol. 2024, 175, 105737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinonen, M.K.; Schee, K.; Jonassen, C.M.; Lie, A.K.; Nystrand, C.F.; Rangberg, A.; Furre, I.E.; Johansson, M.J.; Tropé, A.; Sjøborg, K.D.; et al. Safety and acceptability of human papillomavirus testing of self-collected specimens: A methodologic study of the impact of collection devices and HPV assays on sensitivity for cervical cancer and high-grade lesions. J. Clin. Virol. 2018, 99–100, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedrão, P.G.; de Carvalho, A.C.; Possati-Resende, J.C.; Cury, F.d.P.; Campanella, N.C.; de Oliveira, C.M.; Fregnani, J.H.T.G. DNA Recovery Using Ethanol-Based Liquid Medium from FTA Card-Stored Samples for HPV Detection. Acta Cytol. 2021, 65, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, K.; Luo, H.; Shen, Z.; Wang, G.; Du, H.; Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Qu, X.; Wu, R.; et al. Evaluation of a new solid media specimen transport card for high risk HPV detection and cervical cancer prevention. J. Clin. Virol. 2016, 76, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tranberg, M.; Jensen, J.S.; Bech, B.H.; Andersen, B. Urine collection in cervical cancer screening—Analytical comparison of two HPV DNA assays. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokan, T.; Ivanus, U.; Jerman, T.; Takac, I.; Arko, D. Long term results of follow-up after HPV self-sampling with devices Qvintip and HerSwab in women non-attending cervical screening programme. Radiol. Oncol. 2021, 55, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ozawa, N.; Kurokawa, T.; Hareyama, H.; Tanaka, H.; Satoh, M.; Metoki, H.; Suzuki, M. Evaluation of the feasibility of human papillomavirus sponge-type self-sampling device at Japanese colposcopy clinics. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2023, 49, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ma’som, M.; Bhoo-Pathy, N.; Nasir, N.H.; Bellinson, J.; Subramaniam, S.; Ma, Y.; Yap, S.H.; Goh, P.P.; Gravitt, P.; Woo, Y.L. Attitudes and factors affecting acceptability of self-administered cervicovaginal sampling for human papillomavirus (HPV) genotyping as an alternative to Pap testing among multiethnic Malaysian women. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Latsuzbaia, A.; Vanden Broeck, D.; Van Keer, S.; Weyers, S.; Tjalma, W.A.A.; Doyen, J.; Donders, G.; De Sutter, P.; Vorsters, A.; Peeters, E.; et al. Clinical Performance of the RealTime High Risk HPV Assay on Self-Collected Vaginal Samples within the VALHUDES Framework. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0163122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tiiti, T.A.; Mashishi, T.L.; Nkwinika, V.V.; Molefi, K.A.; Benoy, I.; Bogers, J.; Selabe, S.G.; Lebelo, R.L. Evaluation of ILEX SelfCerv for Detection of High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Infection in Gynecology Clinic Attendees at a Tertiary Hospital in South Africa. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lichtenfels, M.; Lorenzi, N.P.C.; Tacla, M.; Yokochi, K.; Frustockl, F.; Silva, C.A.; Silva, A.L.D.; Termini, L.; Farias, C.B. A New Brazilian Device for Cervical Cancer Screening: Acceptability and Accuracy of Self-sampling. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 2023, 45, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aranda Flores, C.E.; Gomez Gutierrez, G.; Ortiz Leon, J.M.; Cruz Rodriguez, D.; Sørbye, S.W. Self-collected versus clinician-collected cervical samples for the detection of HPV infections by 14-type DNA and 7-type mRNA tests. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Ouyang, Y.; Hillemanns, P.; Jentschke, M. Excellent analytical clinical performance of a dry self-sampling device for human papillomavirus detection in an urban Chinese referral population. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2016, 42, 1839–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, D.; Keung, M.H.T.; Huang, Y.; McDermott, T.L.; Romano, J.; Saville, M.; Brotherton, J.M.L. Self-Collection for Cervical Screening Programs: From Research to Reality. Cancers 2020, 12, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Daponte, N.; Valasoulis, G.; Michail, G.; Magaliou, I.; Daponte, A.I.; Garas, A.; Grivea, I.; Bogdanos, D.P.; Daponte, A. HPV-Based Self-Sampling in Cervical Cancer Screening: An Updated Review of the Current Evidence in the Literature. Cancers 2023, 15, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Islam, J.Y.; Mutua, M.M.; Kabare, E.; Manguro, G.; Hudgens, M.G.; Poole, C.; Olshan, A.F.; Wheeler, S.B.; McClelland, R.S.; Smith, J.S. High-risk Human Papillomavirus Messenger RNA Testing in Wet and Dry Self-collected Specimens for High-grade Cervical Lesion Detection in Mombasa, Kenya. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2020, 47, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Megersa, B.S.; Bussmann, H.; Bärnighausen, T.; Muche, A.A.; Alemu, K.; Deckert, A. Community cervical cancer screening: Barriers to successful home-based HPV self-sampling in Dabat district, North Gondar, Ethiopia. A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mremi, A.; Linde, D.S.; Mchome, B.; Mlay, J.; Schledermann, D.; Blaakaer, J.; Rasch, V. Acceptability and feasibility of self-sampling and follow-up attendance after text message delivery of human papillomavirus results: A cross-sectional study nested in a cohort in rural Tanzania. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2021, 100, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colonetti, T.; Rodrigues Uggioni, M.L.; Meller Dos Santos, A.L.; Michels Uggioni, N.; Uggioni Elibio, L.; Balbinot, E.L.; Grande, A.J.; Rosa, M.I. Self-sampling for HPV testing in cervical cancer screening: A scoping review. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 296, 20–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asare, M.; Abah, E.; Obiri-Yeboah, D.; Lowenstein, L.; Lanning, B. HPV Self-Sampling for Cervical Cancer Screening among Women Living with HIV in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: What Do We Know and What Can Be Done? Healthcare 2022, 10, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maza, M.; Meléndez, M.; Herrera, A.; Hernández, X.; Rodríguez, B.; Soler, M.; Alfaro, K.; Masch, R.; Conzuelo-Rodríguez, G.; Obedin-Maliver, J.; et al. Cervical Cancer Screening with Human Papillomavirus Self-Sampling Among Transgender Men in El Salvador. LGBT Health 2020, 7, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Caleia, A.I.; Pires, C.; Pereira, J.F.; Pinto-Ribeiro, F.; Longatto-Filho, A. Self-Sampling as a Plausible Alternative to Screen Cervical Cancer Precursor Lesions in a Population with Low Adherence to Screening: A Systematic Review. Acta Cytol. 2020, 64, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, P.T.; Kennedy, C.E.; de Vuyst, H.; Narasimhan, M. Self-sampling for human papillomavirus (HPV) testing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekuria, S.F.; Timmermans, S.; Borgfeldt, C.; Jerkeman, M.; Johansson, P.; Linde, D.S. HPV self-sampling versus healthcare provider collection on the effect of cervical cancer screening uptake and costs in LMIC: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2023, 12, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murchland, A.R.; Gottschlich, A.; Bevilacqua, K.; Pineda, A.; Sandoval-Ramírez, B.A.; Alvarez, C.S.; Ogilvie, G.S.; Carey, T.E.; Prince, M.; Dean, M.; et al. HPV self-sampling acceptability in rural and indigenous communities in Guatemala: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrossi, S.; Thouyaret, L.; Herrero, R.; Campanera, A.; Magdaleno, A.; Cuberli, M.; Barletta, P.; Laudi, R.; Orellana, L. Effect of self-collection of HPV DNA offered by community health workers at home visits on uptake of screening for cervical cancer (the EMA study): A population-based cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Glob. Health 2015, 3, e85–e94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, T.; Wubneh, S.B.; Handebo, S.; Debalkie, G.; Ayanaw, Y.; Alemu, K.; Jede, F.; Doeberitz, M.K.; Bussmann, H. Genital self-sampling for HPV-based cervical cancer screening: A qualitative study of preferences and barriers in rural Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottschlich, A.; Payne, B.A.; Trawin, J.; Albert, A.; Jeronimo, J.; Mitchell-Foster, S.; Mithani, N.; Namugosa, R.; Naguti, P.; Pedersen, H.; et al. Community-integrated self-collected HPV-based cervix screening in a low-resource rural setting: A pragmatic, cluster-randomized trial. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camara, H.; Zhang, Y.; Lafferty, L.; Vallely, A.J.; Guy, R.; Kelly-Hanku, A. Self-collection for HPV-based cervical screening: A qualitative evidence meta-synthesis. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Joseph, N.T.; Namuli, A.; Kakuhikire, B.; Baguma, C.; Juliet, M.; Ayebare, P.; Ahereza, P.; Tsai, A.C.; Siedner, M.J.; Randall, T.R.; et al. Implementing community-based human papillomavirus self-sampling with SMS text follow-up for cervical cancer screening in rural, southwestern Uganda. J. Glob. Health 2021, 11, 04036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moss, J.L.; Entenman, J.; Stoltzfus, K.; Liao, J.; Onega, T.; Reiter, P.L.; Klesges, L.M.; Garrow, G.; Ruffin, M.T., IV. Self-sampling tools to increase cancer screening among underserved patients: A pilot randomized controlled trial. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2024, 8, pkad103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Datta, G.; Mayrand, M.; Qureshi, S.; Ferre, N.; Gauvin, L. HPV sampling options for cervical cancer screening: Preferences of Urban-Dwelling Canadians in a changing paradigm. Curr. Oncol. 2020, 27, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moxham, R.; Moylan, P.; Duniec, L.; Fisher, T.; Furestad, E.; Manolas, P.; Scott, N.; Oam, D.K.; Finlay, S. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, intentions and behaviours of Australian Indigenous women from NSW in response to the National Cervical Screening Program changes: A qualitative study. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2021, 13, 100195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racey, C.S.; Gesink, D.C. Barriers and Facilitators to cervical cancer screening among women in rural Ontario, Canada: The role of Self-Collected HPV Testing. J. Rural. Health 2015, 32, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adcock, A.; Cram, F.; Lawton, B.; Geller, S.; Hibma, M.; Sykes, P.; MacDonald, E.J.; Dallas-Katoa, W.; Rendle, B.; Cornell, T.; et al. Acceptability of self-taken vaginal HPV sample for cervical screening among an under-screened Indigenous population. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019, 59, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakewich, P.; Wood, B.; Davey, C.; Laframboise, A.; Zehbe, I. Colonial legacy and the experience of First Nations women in cervical cancer screening: A Canadian multi-community study. Crit. Public Health 2015, 26, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Possati-Resende, J.C.; De Lima Vazquez, F.; De Paula Pantano, N.; Fregnani, J.H.T.G.; Mauad, E.C.; Longatto-Filho, A. Implementation of a cervical cancer screening strategy using HPV Self-Sampling for women living in rural areas. Acta Cytol. 2019, 64, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tratt, E.; Sarmiento, I.; Gamelin, R.; Nayoumealuk, J.; Andersson, N.; Brassard, P. Fuzzy cognitive mapping with Inuit women: What needs to change to improve cervical cancer screening in Nunavik, northern Quebec? BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, I.; Jones, D.; Chen, H.; Macleod, U. Interventions to improve the uptake of cervical cancer screening among lower socioeconomic groups: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2017, 111, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, A.; Holyk, T.; Taylor, D.; Wenninger, C.; Sandford, J.; Smith, L.; Ogilvie, G.; Thomlinson, A.; Mitchell-Foster, S. Highlighting strengths and resources that increase ownership of cervical cancer screening for Indigenous communities in Northern British Columbia: Community-driven approaches. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 155, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, R.B.; Guido, R.S.; Castle, P.E.; Chelmow, D.; Einstein, M.H.; Garcia, F.; Huh, W.K.; Kim, J.J.; Moscicki, A.B.; Nayar, R.; et al. 2019 ASCCP Risk-Based Management Consensus Guidelines Committee. 2019 ASCCP Risk-Based Management Consensus Guidelines for Abnormal Cervical Cancer Screening Tests and Cancer Precursors. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2020, 24, 102–131, Erratum in J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2020, 24, 427. https://doi.org/10.1097/LGT.0000000000000563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Woo, Y.L.; Khoo, S.P.; Gravitt, P.; Hawkes, D.; Rajasuriar, R.; Saville, M. The Implementation of a Primary HPV Self-Testing Cervical Screening Program in Malaysia through Program ROSE-Lessons Learnt and Moving Forward. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 7379–7387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zehbe, I.; Wakewich, P.; King, A.; Morrisseau, K.; Tuck, C. Self-administered versus provider-directed sampling in the Anishinaabek Cervical Cancer Screening Study (ACCSS): A qualitative investigation with Canadian First Nations women. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e017384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezei, A.K.; Armstrong, H.L.; Pedersen, H.N.; Campos, N.G.; Mitchell, S.M.; Sekikubo, M.; Byamugisha, J.K.; Kim, J.J.; Bryan, S.; Ogilvie, G.S. Cost-effectiveness of cervical cancer screening methods in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hariprasad, R.; Bagepally, B.S.; Kumar, S.; Pradhan, S.; Gurung, D.; Tamang, H.; Sharma, A.; Bhatnagar, T. Cost-utility analysis of primary HPV testing through home-based self-sampling in comparison to visual inspection using acetic acid for cervical cancer screening in East district, Sikkim, India, 2023. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0300556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Boyard, J.; Caille, A.; Brunet-Houdard, S.; Sengchanh-Vidal, S.; Giraudeau, B.; Marret, H.; Rolland-Lozachmeur, G.; Rusch, E.; Gaudy-Graffin, C.; Haguenoer, K. A Home-Mailed Versus General Practitioner-Delivered Vaginal Self-Sampling Kit for Cervical Cancer Screening: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial with a Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. J. Womens Health 2022, 31, 1472–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malone, C.; Barnabas, R.V.; Buist, D.S.M.; Tiro, J.A.; Winer, R.L. Cost-effectiveness studies of HPV self-sampling: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2020, 132, 105953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aarnio, R.; Östensson, E.; Olovsson, M.; Gustavsson, I.; Gyllensten, U. Cost-effectiveness analysis of repeated self-sampling for HPV testing in primary cervical screening: A randomized study. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, Z.H.; An, Y.J.; Chu, Z.X.; Li, X.R.; Hou, A.Y.; Jiang, Y.J.; Hu, Q.H. Cost-effectiveness of self-sampling and enhanced strategies for HPV prevention among men who have sex with men in China: A modeling study. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wedisinghe, L.; Sasieni, P.; Currie, H.; Baxter, G. The impact of offering multiple cervical screening options to women whose screening was overdue in Dumfries and Galloway Scotland. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 29, 101947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Self-Care Interventions: Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Self-Sampling as Part of Cervical Cancer Screening. 2020. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/366868/WHO-SRH-23.1-eng.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Wentzensen, N.; Massad, L.S.; Clarke, M.A.; Garcia, F.; Smith, R.; Murphy, J.; Guido, R.; Reyes, A.; Phillips, S.; Berman, N.; et al. Self-Collected Vaginal Specimens for HPV Testing: Recommendations From the Enduring Consensus Cervical Cancer Screening and Management Guidelines Committee. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2025, 29, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ebisch, R.M.; Siebers, A.G.; Bosgraaf, R.P.; Massuger, L.F.; Bekkers, R.L.; Melchers, W.J. Triage of high-risk HPV positive women in cervical cancer screening. Expert. Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2016, 16, 1073–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, Y.L.; Gravitt, P.; Khor, S.K.; Ng, C.W.; Saville, M. Accelerating action on cervical screening in lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs) post COVID-19 era. Prev. Med. 2021, 144, 106294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- National Cancer Institute. FDA Approves HPV Tests That Allow for Self-Collection in a Health Care Setting. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2024/fda-hpv-test-self-collection-health-care-setting (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Watson, M.; Benard, V.; King, J.; Crawford, A.; Saraiya, M. National assessment of HPV and Pap tests: Changes in cervical cancer screening, National Health Interview Survey. Prev. Med. 2017, 100, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Self-Sampling Device | Self-Sampling Approach | Producer | Validated HPV Testing Platforms | Studies Testing the Devices |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aptima Multitest Swab Specimen Collection Kit | Vaginal | Hologic Inc., Marlborough, MA, USA | Hologic Aptima | [51,52] |

| BGI Sentis HPV card | Vaginal | BGI Genomics, Shenzhen, China | Sentis™ HPV Genotyping Test | [53,54] |

| Catch-All Swab | Vaginal | Epicentre, Madison, WI, USA | [55] | |

| Cervex-Brush®® Combi | Vaginal | Rovers Medical Devices, B. V, Oss, The Netherlands | Roche Cobas 4800, BD Onclarity, Hologic Aptima | [56,57,58,66] |

| Cepillo Endocervical/Cervical Brush/Cyto-Brush + DNA sample storage card | Vaginal | Ningbo HLS Medical Products Co. Ltd., Ningbo, China BGI Biotechnology (Wuhan) Co. Ltd., Wuhan, China | BD Onclarity | [54] |

| Colli-Pee™ | Urine | Novosanis, Wijnegem, Belgium | Roche Cobas 4800, Abbott Alinity m HR HPV, BD Onclarity, Hologic Aptima | [40,56,57,75] |

| Copan ESwab®® | Vaginal | Copan Italia, Brescia, Italy | ABI GeneAmp®® 9700 PCR System | [60] |

| Cytobrush Plus | Vaginal | Medscand, Malmo, Sweden | Roche Cobas 4800, BD On-clarity, Hologic Aptima | [61] |

| Dacron swab | Vaginal | Invista North America S.a.r.l., Wichita, KS, USA | Hybrid Capture®® 2 High-Risk HPV DNA Test (HC2; Qiagen) | [62,63] |

| Deplphi Screener | Vaginal | Rovers Medical Devices B.V., Oss, The Netherlands | Roche Cobas 4800, Abbott Alinity m HR HPV, Hologic Aptima | [39,58,64,75] |

| Digene cervical brush | Vaginal | Digene Corporation, Gaithersburg, MD, USA | HPV DNA Tests by Cervista | [65] |

| Evalyn brush | Vaginal | Rovers Medical Devices B.V., Oss, The Netherlands | Roche Cobas 4800, Abbott Alinity m HR HPV, BD Onclarity, Hologic Aptima | [39,58,64,65,66,67,75] |

| FLOQSwab | Vaginal | COPAN Diagnostics Inc., Brescia, Italy | Roche Cobas 4800, Abbott Alinity m HR HPV, Hologic Aptima | [40,67,68] |

| Elute Micro Card (FTA card) | Vaginal | GE HealthCare, Hatfield, UK | Roche Cobas 4800, Abbott Alinity m HR HPV | [69,70] |

| Genelock | Urine | ASSAY ASSURE, Sierra Molecular, Princeton, NJ, USA | Roche Cobas 4800 | [71] |

| HerSwab | Vaginal | Eve Medical, Inc., Toronto, Canada | Roche Cobas 4800, Abbott Alinity m HR HPV | [40,55,72] |

| Home Smear Set Plus®® | Vaginal | Asica Medical Industry Co., Ltd. (global network), Tokyo, Japan | Roche Cobas 4800 | [73] |

| “Just for Me” | Vaginal | Preventive Oncology International Inc., Cleveland Heights, OH, USA | Not reported | [74] |

| Mía by Xytotest®® | Vaginal | Mel-Mont Medical, LLC, Mexico City, Mexico | BD Onclarity, Hologic Aptima | [57,66] |

| Multi-Collect swab | Vaginal | Abbott GmbH & Co. KG, Wiesbaden, Germany | Abbott Alinity m HR HPV | [75] |

| SelfCerv Self-Collection Cervical Health Screening Kit | Vaginal | Ilex Medical Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa | Roche Cobas 4800, Hologic Aptima | [76] |

| SelfCervix®® | Vaginal | Not reported | Hologic Aptima | [77] |

| Qvintip | Vaginal | Aprovix AB, Uppsala, Sweden | Roche Cobas 4800, Hologic Aptima, BD Onclarity | [40,72,75,78] |

| Urine Sampler | Urine | Any available | Roche Cobas 4800, Abbott Alinity m HR HPV, Hologic Aptima, BD Onclarity | [45,65,71] |

| Viba brush | Vaginal | Rovers Medical Devices B.V., Oss, The Netherlands | Hologic Aptima | [57] |

| XytoTest medical device | Vaginal | Mel-Mont Medical, Doral, FL, USA | Abbott RealTime HR HPV test | [78] |

| Area of Interest | Barriers | Facilitators |

|---|---|---|

| Logistical | No regular provider or nearby clinic; inconvenient hours; work/child/elder care demands; transport/parking/childcare costs; preference to avoid male clinician; hard-to-navigate services | Home or in-clinic self-sampling; flexible timing; prepaid mail-back kits; option to choose method |

| Procedural | Anticipated pain/discomfort; embarrassment; dislike of speculum/Pap; privacy concerns in small communities | Greater privacy and autonomy with self-collection; fewer intimate procedures |

| Knowledge-related | Fear of doing it “wrong” or self-injury; doubts about HPV test accuracy; low perceived risk; fear of positive result; limited info after abnormal results | Clear step-by-step instructions; helplines/video guides; provider recommendation; option for female provider |

| Cultural and Social | Stigma/taboos around bodies/sexuality; recent immigration; distrust from historical harms; services not culturally safe | Co-designed, culturally sensitive materials; community-driven delivery; affirming caregiving/traditional roles; sustained trust-building |

| Self-Sampling Kit | Cost per Kit (USD) | Comments/Cost-Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|

| Evalyn Brush | ~$5–7 | Validated in multiple trials in European countries and now extensively used; cost-effective for mass screening |

| Copan FLOQSwab/ESwab | ~$4–6 | Validated in many studies; cost-effective for LMICs; easy to store and transport |

| Delphi Screener | ~$7–9 | Preferable for high accuracy; has a slightly higher cost |

| Qvintip | ~$6–8 | Validated in large population programs; has good acceptance; lower material cost |

| HerSwab | ~$8–10 | High user satisfaction; however, slightly more expensive |

| Colli-Pee™ | ~$9–11 | Higher price due to integrated preservation system; however, shows cost-effectiveness due to high acceptance and high participation rate |

| BGI Sentis Card/FTA Card | ~$3–5 | Card; low cost of the card; suitable for remote or low-resource regions |

| SelfCerv | ~$4–6 | Designed for LMICs; cost-effective |

| Mía by XytoTest® | ~$5–7 | Validated in Latin America; low cost and high acceptability |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rakhat, A.; Marat, A.; Sakhipova, G.; Sakko, Y.; Aimagambetova, G. Self-Sampling Modality for Cervical Cancer Screening: Overview of the Diagnostic Approaches and Sampling Devices. Sci 2026, 8, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci8010005

Rakhat A, Marat A, Sakhipova G, Sakko Y, Aimagambetova G. Self-Sampling Modality for Cervical Cancer Screening: Overview of the Diagnostic Approaches and Sampling Devices. Sci. 2026; 8(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci8010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleRakhat, Altynshash, Aizada Marat, Gulnara Sakhipova, Yesbolat Sakko, and Gulzhanat Aimagambetova. 2026. "Self-Sampling Modality for Cervical Cancer Screening: Overview of the Diagnostic Approaches and Sampling Devices" Sci 8, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci8010005

APA StyleRakhat, A., Marat, A., Sakhipova, G., Sakko, Y., & Aimagambetova, G. (2026). Self-Sampling Modality for Cervical Cancer Screening: Overview of the Diagnostic Approaches and Sampling Devices. Sci, 8(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci8010005