Identifying Features of LLM-Resistant Exam Questions: Insights from Artificial Intelligence (AI)–Student Performance Comparisons

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

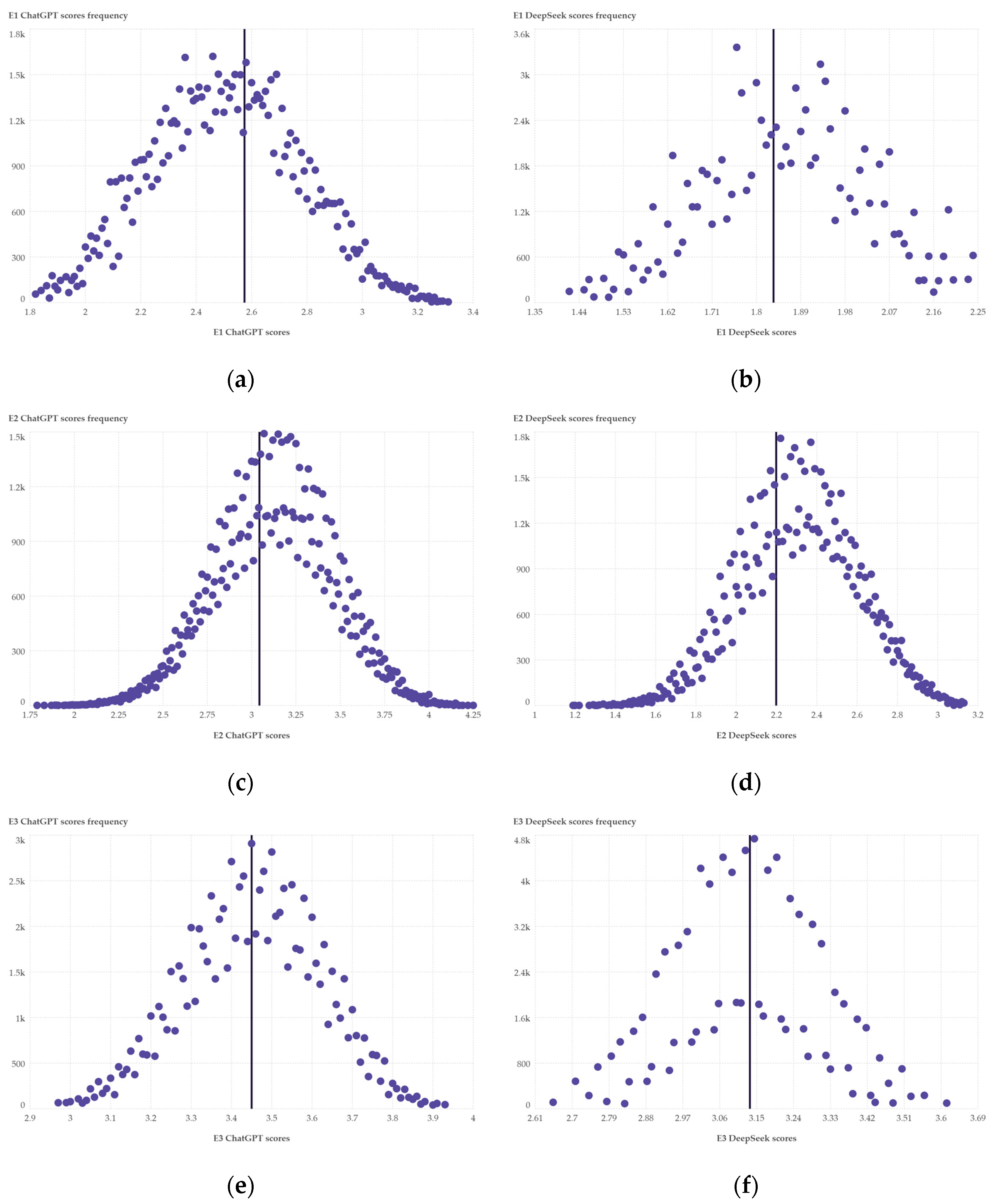

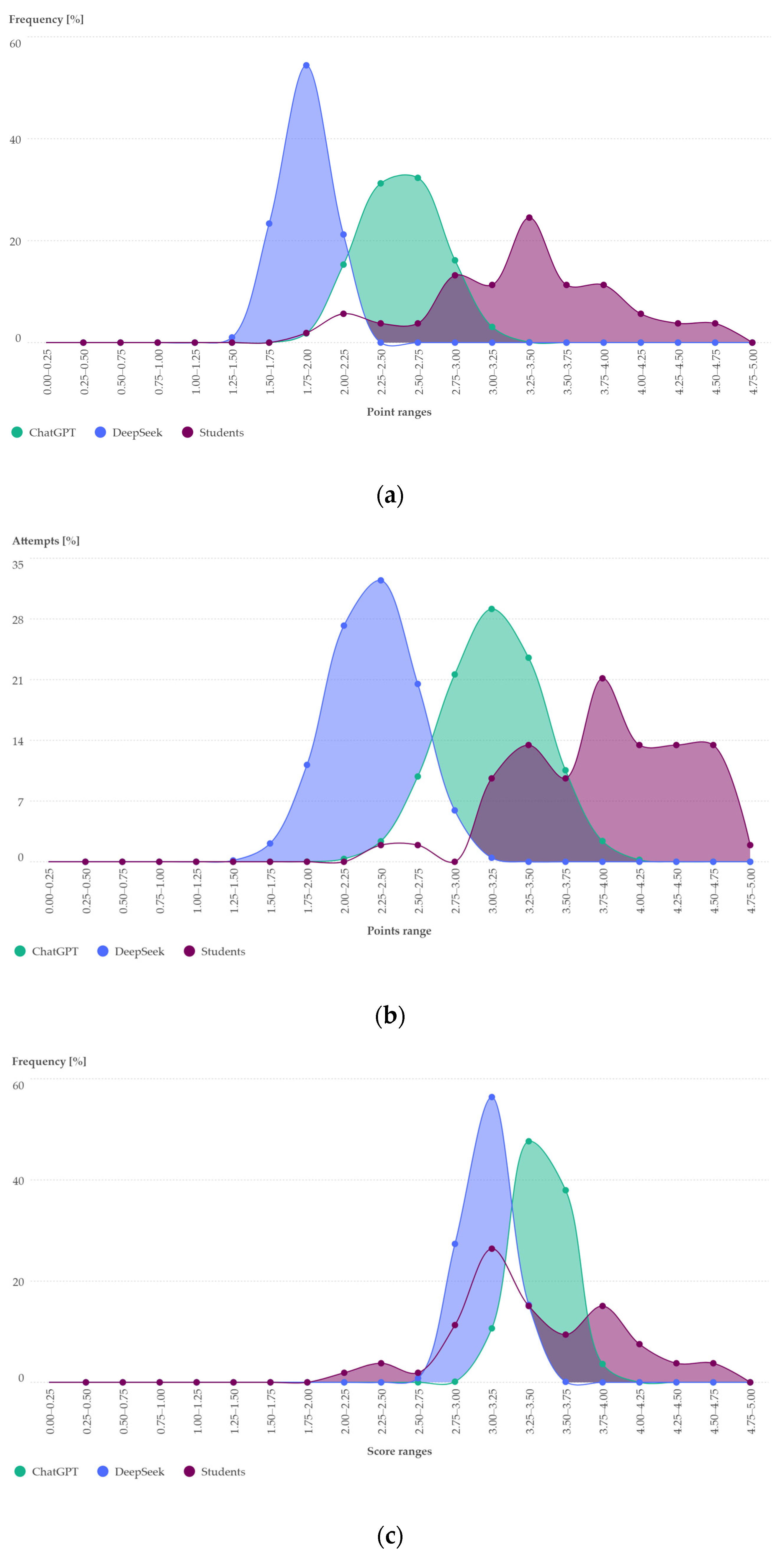

3.1. Score Distribution of LLM Recorded Responses and Student Examination Score Comparison

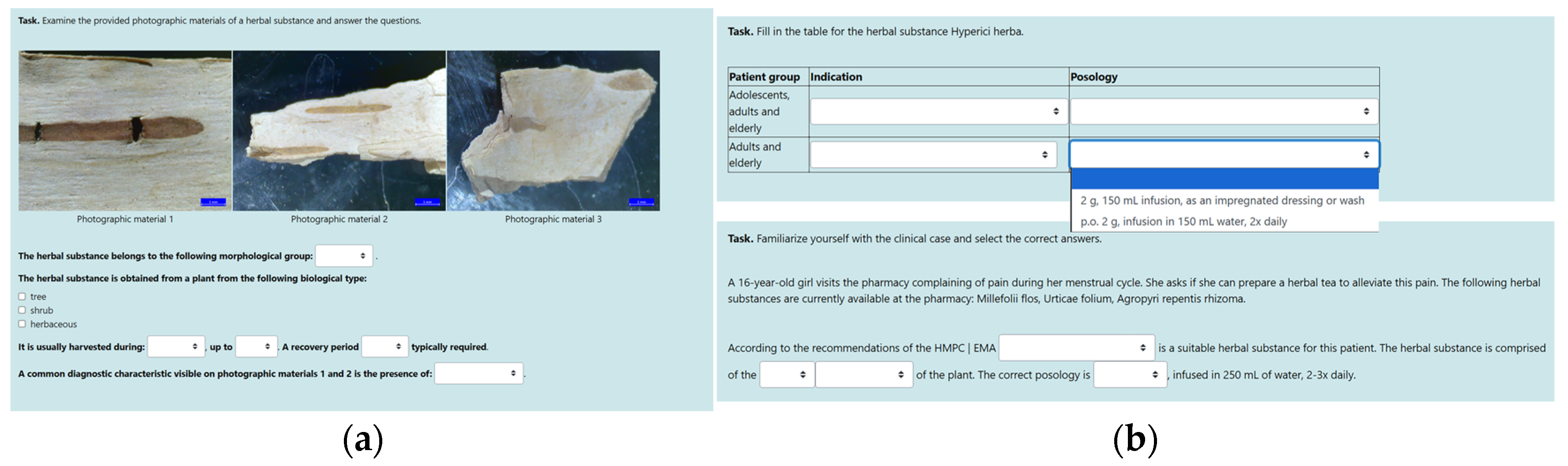

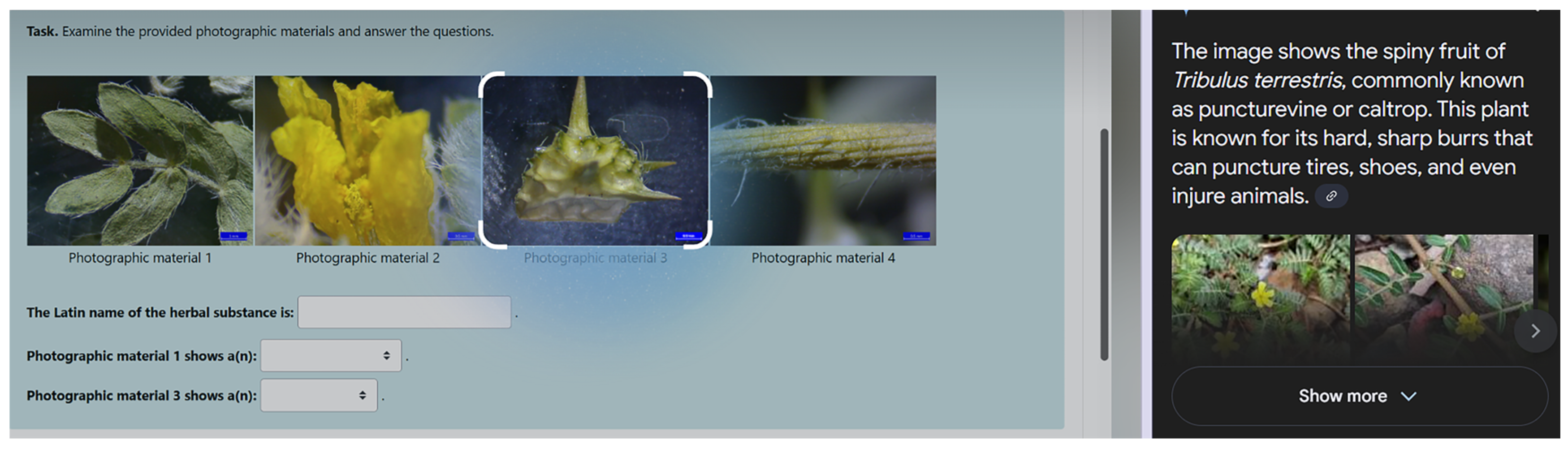

3.2. Scores Attained per Examination Category, Relative to Student Performance

3.3. Exploring the Connection Between the Facility Index and LLM Scores

3.4. Google Lens and Pl@ntNet Capabilities in Identification of Herbal Substances Featured on Pharmacognosy Examinations

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| CV | Computer vision |

| E1 | Examination 1 |

| E2 | Examination 2 |

| E3 | Examination 3 |

| FIB | Fill in the blanks |

| DD | Drag and drop |

| LLM | Large language model |

| MC | Multiple choice |

| TF | True or false |

Appendix A

| Thematic Area | Topics Covered | Key Concepts/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Foundations of Pharmacognosy | Nature, objectives, tasks | Basic concepts and approaches |

| Historical development | Ancient sources and contemporary practices | |

| Medicinal plants and herbal substances: concepts, classification, nomenclature | Taxonomy Herbal substances nomenclature | |

| Interdisciplinary role of pharmacognosy across sciences | Connections to pharmacology, pharmacotherapy, technology of pharmaceutical forms and legislation | |

| Discovery, Sources and Products of Natural Origin | Modern approaches to medicinal plant discovery | Ethnopharmacology, ethnobotany, phylogenetics, chemotaxonomy |

| Products of natural origin | Herbal substances Preparations (teas, oils, fats and extracts) | |

| Plant Material Handling | Collection, processing, storage, cultivation | Good Agricultura and Collection Practices (GACP) |

| Wild plants and biodiversity as sources | Distribution of natural resources Bioaccumulation Cultivation | |

| Pharmacognostic study design | Planning and key considerations | |

| Types of preparations and extraction techniques | Specific requirements in overview of constituents | |

| Standards and Regulations | European Pharmacopeia | Structure Quality control methods Classification of preparations Reference standards; marker compounds |

| Medicine agencies | Bulgarian Drug Agency European Medicines Agency—Herbal Medicinal Products Committee Definitions Declaration of extracts | |

| Analytical and Diagnostic Methods | Macroscopic, microscopic, pharmacognostic analyses | Morphological and anatomical features Staining and observation techniques |

| Physiochemical pharmacognostic analyses | Loss on drying Ash content Swelling index | |

| Herbal Medicines | Definitions, classification, safety and efficacy | Traditional and well-established use Combination herbal medicinal products (species) Use in sensitive populations Therapeutic indications, posology, counterindications, period of use. |

| Biologically Active Compounds | Isolation and analysis of bioactive compounds | Methods and screening for activity |

| Primary and secondary metabolites, biosynthetic pathways | Shikimate, mevalonate, malonate, etc. | |

| Chemical groups of natural compounds | Carbohydrates Lipids and lipoids Phenols Flavonoids |

| Quiz, Examination or Exam | Points | Points [%] |

|---|---|---|

| Taxonomy and nomenclature quiz | 18 | 10.91 |

| Examination 1 | 5 | 3.03 |

| Examination 2 | 5 | 3.03 |

| Examination 3 | 5 | 3.03 |

| Practical exam | 33 | 20.00 |

| Final exam | 99 | 60.00 |

| Thematic Section | Categories | Point Value | Questions | Question Type | Facility Index [%] | Discrimination Index [%] | Cognitive Dimension | Competencies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| European pharmacopeia | C1. General notices | 0.2 | 1.1 | Cloze (MC; FIB) | 81 | 33 | Remember | 7.7 Ability to maintain current knowledge of relevant legislation and codes of pharmacy practice; 10.37 legislation and professional ethics; |

| 1.2 | 76 | |||||||

| 1.3 | 74 | |||||||

| C2. Ph. Eur. structure | 0.4 | 2.1 | Cloze (MC) | 72 | 10 | Apply, analyze | 7.7 Ability to maintain current knowledge of relevant legislation and codes of pharmacy practice; 9.21 ability to communicate in English and/or locally relevant languages; 10.37 legislation and professional ethics; 11.39 current knowledge of good manufacturing practice (GMP) and of good laboratory practice (GLP) | |

| 2.2 | 74 | |||||||

| 2.3 | 56 | |||||||

| 2.4 | 74 | |||||||

| C3. Monograph structure | 0.4 | 3.1 | Cloze (MC) | 64 | 11 | Remember, analyze | 7.7 Ability to maintain current knowledge of relevant legislation and codes of pharmacy practice; 10.37 legislation and professional ethics; 11.39 current knowledge of good manufacturing practice (GMP) and of good laboratory practice (GLP) | |

| 3.2 | 70 | |||||||

| 3.3 | 63 | |||||||

| Pharmacognosy—basic concepts | C4. Basic concepts | 0.1 | 4.1 | Cloze (MC; FIB) | 79 | 59 | Remember, apply | 9.21 Ability to communicate in English and/or locally relevant languages |

| 4.2 | 72 | |||||||

| 4.3 | 60 | |||||||

| C5. Chemotaxonomy | 0.4 | 5.1 | DD | 86 | 28 | Remember, apply | 9.21 Ability to communicate in English and/or locally relevant languages; 10.24 plant and animal biology; 10.27 organic and medicinal/pharmaceutical chemistry | |

| 5.2 | 80 | |||||||

| 5.3 | 73 | |||||||

| C6. Morphological plant parts | 0.5 | 6.1 | Cloze (MC) | 77 | 43 | Remember, analyze | 10.24 Plant and animal biology; 11.39 current knowledge of good manufacturing practice (GMP) and of good laboratory practice (GLP) | |

| 6.2 | 82 | |||||||

| 6.3 | 66 | |||||||

| 6.4 | 70 | |||||||

| C7. Primary processing and GACP | 0.1 | 7.1 | MC | 91 | 46 | Remember, understand | 11.39 Current knowledge of good manufacturing practice (GMP) and of good laboratory practice (GLP) | |

| 7.2 | 91 | |||||||

| 7.3 | 92 | |||||||

| 7.4 | 71 | |||||||

| HMPC|EMA—recommendations | C8. Case studies | 0.5 | 8.1 | Cloze (MC) | 58 | 25 | Remember, understand, apply, analyze, | 9.21 Ability to communicate in English and/or locally relevant languages; 10.30 anatomy and physiology; medical terminology; 10.33 pharmacotherapy and pharmaco-epidemiology; 13.46 retrieval and interpretation of relevant information on the patient’s clinical background; 17.63 provision of informed support for patients in selection and use of non-prescription medicines for minor ailments (e.g., cough remedies …) |

| 8.2 | 91 | remember, understand, apply | ||||||

| C9. Therapeutic area, indication, patient population, posology | 0.5 | 9.1 | Cloze (MC) | 75 | 22 | Remember, apply | 10.33 Pharmacotherapy and pharmaco-epidemiology; 17.63 provision of informed support for patients in selection and use of non-prescription medicines for minor ailments (e.g., cough remedies…) | |

| 9.2 | 50 | |||||||

| 9.3 | 69 | |||||||

| Macroscopic analysis | C10. Identification | 0.7 | 10.1 | Cloze (MC) | 62 | 25 | Remember, analyze | 9.21 Ability to communicate in English and/or locally relevant languages; 10.24 plant and animal biology |

| 10.2 | 33 | |||||||

| 10.3 | 55 | |||||||

| C11. Adulteration | 0.2 | 11.1 | (MC) | 81 | 48 | Remember | 9.21 Ability to communicate in English and/or locally relevant languages; 10.24 plant and animal biology | |

| 11.2 | 84 | |||||||

| 11.3 | 56 | |||||||

| Microscopic analysis | C12. Methodology | 0.2 | 12.1 | Cloze (FIB) | 59 | 44 | Remember, understand | 7.6 Ability to design and conduct research using appropriate methodology; 7.7 ability to maintain current knowledge of relevant legislation and codes of pharmacy practice; 9.21 ability to communicate in English and/or locally relevant languages; 10.37 legislation and professional ethics |

| 12.2 | 45 | |||||||

| 12.3 | 59 | |||||||

| C13. Diagnostic characteristics | 0.1 | 13.1 | Cloze (MC) | 83 | 14 | Remember, apply, analyze | 10.24 Plant and animal biology | |

| 13.2 | 60 | |||||||

| 13.3 | 76 | |||||||

| 13.4 | 65 | |||||||

| C14. Differential staining | 0.3 | 14.1 | Cloze (MC) | 72 | 29 | Remember, understand, apply, analyze | 10.24 Plant and animal biology; 10.27 organic and medicinal/pharmaceutical chemistry; 10.29 general and applied biochemistry (medicinal and clinical) | |

| 14.2 | 71 | |||||||

| 14.3 | 70 | |||||||

| 14.4 | 52 | |||||||

| C15. Quality standards and adulteration | 0.4 | 15.1 | Cloze (FIB) | 46 | 25 | Remember, understand, apply, analyze, evaluate | 10.24 Plant and animal biology; 10.37 legislation and professional ethics | |

| 15.2 | 39 | |||||||

| 15.3 | 51 |

| Thematic Section | Categories | Point Value | Questions | Question Type | Facility Index [%] | Discrimination Index [%] | Cognitive Dimension | Competencies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional herbal medicinal products | C1. Justification of traditional use requirements | 0.2 | 1.1 | FIB | 88 | 30 | Remember | 7.7 Ability to maintain current knowledge of relevant legislation and codes of pharmacy practice; 10.37 legislation and professional ethics. |

| 1.2 | 93 | |||||||

| C2. Therapeutic indications and use | 0.4 | 2.1 | DD | 76 | 42 | Remember, apply | 17.63 Provision of informed support for patients in selection and use of non-prescription medicines for minor ailments (e.g., cough remedies…) | |

| 2.2 | 65 | |||||||

| 2.3 | 73 | |||||||

| 2.4 | 68 | |||||||

| Extraction processes | C3. Preliminary processing of plant materials | 0.1 | 3.1 | TF | 100 | 15 | Remember, understand | 7.6 Ability to design and conduct research using appropriate methodology |

| 3.2 | 38 | |||||||

| 3.3 | 83 | |||||||

| 3.4 | 85 | |||||||

| C4. Extraction types | 0.2 | 4.1 | DD | 59 | 10 | Remember, understand | 10.38 Current knowledge of design, synthesis, isolation, characterization and biological evaluation of active substances | |

| 4.2 | MC | 86 | ||||||

| 4.3 | 80 | |||||||

| 4.4 | FIB | 79 | ||||||

| 4.5 | 91 | |||||||

| 4.6 | DD | 78 | ||||||

| 4.7 | 78 | |||||||

| C5. Solvents | 0.2 | 5.1 | DD | 98 | 27 | Remember, understand | 10.27 Organic and medicinal/pharmaceutical chemistry | |

| 5.2 | 68 | |||||||

| 5.3 | 48 | |||||||

| 5.4 | 54 | |||||||

| 5.5 | 75 | |||||||

| Metabolic pathways | C6. Primary and secondary metabolites | 0.2 | 6.1 | FIB | 82 | 8 | Remember | 10.29 General and applied biochemistry (medicinal and clinical) |

| 6.2 | 87 | |||||||

| 6.3 | 97 | |||||||

| C7. Biosynthetic pathways | 0.1 | 7.1 | Cloze (MC) | 65 | 20 | Remember | 10.29 General and applied biochemistry (medicinal and clinical) | |

| 7.2 | 81 | |||||||

| 7.3 | 56 | |||||||

| 7.4 | 61 | |||||||

| Macroscopic analysis | C8. Identification | 0.3 | 8.1 | DD | 64 | 13 | Remember, analyze | 9.21 Ability to communicate in English and/or locally relevant languages; 10.24 plant and animal biology |

| 8.2 | 92 | |||||||

| 8.3 | 77 | |||||||

| 8.4 | 67 | |||||||

| 8.5 | 81 | |||||||

| C9. Diagnostic characteristics | 0.3 | 9.1 | MC | 77 | 22 | Remember | 9.21 Ability to communicate in English and/or locally relevant languages; 10.24 plant and animal biology | |

| 9.2 | 75 | |||||||

| 9.3 | 63 | |||||||

| 9.4 | 97 | |||||||

| 9.5 | 72 | |||||||

| 9.6 | 82 | |||||||

| Microscopic analysis | C10. Diagnostic characteristics | 0.3 | 10.1 | DD | 83 | 41 | Remember | 9.21 Ability to communicate in English and/or locally relevant languages; 10.24 plant and animal biology |

| 10.2 | 83 | |||||||

| 10.3 | 63 | |||||||

| 10.4 | 97 | |||||||

| 10.5 | FIB | 75 | ||||||

| 10.6 | 63 | |||||||

| 10.7 | 84 | |||||||

| 10.8 | 81 | |||||||

| 10.9 | 88 | |||||||

| C11. Micromorphology | 0.3 | 11.1 | DD | 100 | 47 | Remember | 10.24 Plant and animal biology | |

| 11.2 | 85 | |||||||

| 11.3 | 45 | |||||||

| 11.4 | 77 | |||||||

| 11.5 | 60 | |||||||

| 11.6 | 78 | |||||||

| C12. Identification | 0.3 | 12.1 | MC | 78 | 6 | Remember, analyze | 10.24 Plant and animal biology | |

| 12.2 | 60 | |||||||

| 12.3 | FIB | 80 | ||||||

| 12.4 | MC | 55 | ||||||

| 12.5 | 67 | |||||||

| C13. Microchemical reactions | 0.3 | 13.1 | MC | 75 | 15 | Remember | 10.28 Analytical chemistry | |

| 13.2 | 100 | |||||||

| 13.3 | TF | 71 | ||||||

| 13.4 | 43 | |||||||

| 13.5 | 50 | |||||||

| 13.6 | 17 | |||||||

| 13.7 | DD | 92 | ||||||

| 13.8 | 64 | |||||||

| C14. Starches | 0.3 | 14.1 | MC | 50 | 17 | Remember, analyze | 10.24 Plant and animal biology; 10.37 legislation and professional ethics | |

| 14.2 | 85 | |||||||

| 14.3 | 77 | |||||||

| 14.4 | 25 | |||||||

| 14.5 | 93 | |||||||

| Pharmacognostic analyses | C15. Loss on Drying and Ash—general concepts | 0.3 | 15.1 | DD | 93 | 9 | Remember, apply | 10.37 Legislation and professional ethics |

| 15.2 | 93 | |||||||

| 15.3 | FIB | 80 | ||||||

| 15.4 | 93 | |||||||

| 15.5 | DD | 79 | ||||||

| 15.6 | 55 | |||||||

| 15.7 | 96 | |||||||

| C16. Loss on Drying and calculation | 0.3 | 16.1 | MC | 74 | 6 | Remember, apply | 10.37 Legislation and professional ethics | |

| 16.2 | 67 | |||||||

| 16.3 | 84 | |||||||

| 16.4 | 79 | |||||||

| C17. Ash—calculation | 0.3 | 17.1 | DD | 91 | 41 | Remember, apply | 10.37 Legislation and professional ethics | |

| 17.2 | 78 | |||||||

| 17.3 | MC | 80 | ||||||

| 17.4 | 89 | |||||||

| C18. Swelling index | 0.3 | 18.1 | DD | 87 | 26 | Remember | 7.6 Ability to design and conduct research using appropriate methodology; 10.37 legislation and professional ethics | |

| 18.2 | 85 | |||||||

| 18.3 | 80 | |||||||

| C19. Cotton wool—absorbency | 0.3 | 19.1 | DD | 84 | 14 | Remember | 7.6 Ability to design and conduct research using appropriate methodology: 10.37 legislation and professional ethics | |

| 19.2 | TF | 100 | ||||||

| 19.3 | 50 | |||||||

| 19.4 | 44 |

| Thematic Section | Categories | Point Value | Questions | Question Type | Facility Index [%] | Discrimination Index [%] | Cognitive Dimension | Competencies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General questions | C1. Natural identity of constituents | 0.1 | 1.1 | MC | 100 | 1 | Remember | 9.21 Ability to communicate in English and/or locally relevant languages |

| 1.2 | 67 | |||||||

| 1.3 | 100 | |||||||

| 1.4 | 100 | |||||||

| 1.5 | 100 | |||||||

| C2. General statements on constituents | 0.2 | 2.1 | MC | 67 | 0 | Remember, understand | 10.27 Organic and medicinal/pharmaceutical chemistry; 10.37 legislation and professional ethics | |

| 2.2 | 79 | |||||||

| 2.3 | 75 | |||||||

| C3. Recognizing constituents, medicinal and borderline products | 0.5 | 3.1 | DD | 60 | 47 | Remember, analyze | 7.7 Ability to maintain current knowledge of relevant legislation and codes of pharmacy practice; 10.37 legislation and professional ethics | |

| 3.2 | 32 | |||||||

| 3.3 | 67 | |||||||

| Carbohydrates and waxes | C4. Honey | 0.3 | 4.1 | Cloze (FIB; DD) | 84 | 12 | Remember | 9.21 Ability to communicate in English and/or locally relevant languages; 10.24 plant and animal biology; 10.27 organic and medicinal/pharmaceutical chemistry; 10.31 microbiology; 10.37 legislation and professional ethics |

| 4.2 | 96 | |||||||

| C5. Mannitol | 0.2 | 5.1 | MC | 79 | 0 | Remember, apply | 10.31 Microbiology; 10.32 pharmacology including pharmacokinetics; 10.33 pharmacotherapy and pharmaco-epidemiology; 10.37 legislation and professional ethics | |

| 5.2 | 79 | |||||||

| C6. Waxes | 0.2 | 6.1 | Cloze (FIB; DD) | 100 | 21 | Remember, apply | 9.21 Ability to communicate in English and/or locally relevant languages; 10.34 pharmaceutical technology, including analyses of medicinal products | |

| 6.2 | 65 | |||||||

| Fats and vegetable fatty oils | C7. Quality control of fatty oils | 0.3 | 7.1 | Cloze (FIB; DD) | 87 | 17 | Remember | 9.21 Ability to communicate in English and/or locally relevant languages; 10.34 pharmaceutical technology, including analyses of medicinal products; 10.37 legislation and professional ethics |

| 7.2 | 67 | |||||||

| C8. Extraction and analysis of fatty oils | 0.3 | 8.1 | Cloze (FIB; DD) | 45 | 26 | Remember, analyze | 7.4 Capacity to evaluate scientific data in line with current scientific and technological knowledge; 9.21 ability to communicate in English and/or locally relevant languages; 10.37 legislation and professional ethics | |

| 8.2 | 47 | |||||||

| C9. Structural characteristics of fatty oils | 0.2 | 9.1 | Cloze (DD) | 100 | 26 | Remember, analyze | 10.27 Organic and medicinal/pharmaceutical chemistry | |

| 9.2 | 70 | |||||||

| 9.3 | 100 | |||||||

| 9.4 | 56 | |||||||

| 9.5 | 85 | |||||||

| 9.6 | 75 | |||||||

| C10. Castor oil | 0.3 | 10.1 | Cloze (FIB; DD) | 61 | 15 | Remember | 9.21 Ability to communicate in English and/or locally relevant languages; 10.24 plant and animal biology; 10.27 organic and medicinal/pharmaceutical chemistry | |

| 10.2 | 72 | |||||||

| Therapeutic indications | C11. HMPC | EMA recommendations | 0.35 | 11.1 | Cloze (MC) | 81 | 2 | Remember, apply | 9.21 Ability to communicate in English and/or locally relevant languages; 10.33 pharmacotherapy and pharmaco-epidemiology; 17.63 provision of informed support for patients in selection and use of non-prescription medicines for minor ailments (e.g., cough remedies…) |

| 11.2 | 77 | |||||||

| C12. Risk and adverse effects associated with use | 0.35 | 12.1 | Essay | 80 | 32 | Understand, analyze, evaluate, create | 7.2 Analysis: ability to apply logic to problem solving, evaluating pros and cons and following up on the solution found; 7.3 synthesis: capacity to gather and critically appraise relevant knowledge and to summarize the key points; 7.5 ability to interpret preclinical and clinical evidence-based medical science and apply the knowledge to pharmaceutical practice; 10.32 pharmacology, including pharmacokinetics; 10.33 pharmacotherapy and pharmaco-epidemiology; 13.46 retrieval and interpretation of relevant information on the patient’s clinical background; 17.63 provision of informed support for patients in the selection and use of non-prescription medicines for minor ailments (e.g., cough remedies…) | |

| 12.2 | 76 | |||||||

| 12.3 | 86 | |||||||

| Phenols and flavonoids | C13. Micro-sublimation | 0.3 | 13.1 | Cloze (FIB; DD) | 75 | 13 | Remember, analyze | 10.33 Pharmacotherapy and pharmaco-epidemiology; 17.63 provision of informed support for patients in selection and use of non-prescription medicines for minor ailments (e.g., cough remedies…) |

| 13.2 | 92 | |||||||

| C14. Anthocyanidins | 0.2 | 14.1 | Cloze (DD) | 56 | 51 | Remember | 10.27 Organic and medicinal/pharmaceutical chemistry; 10.28 analytical chemistry | |

| 14.2 | 73 | |||||||

| Macroscopic analysis | C15. Identification | 0.3 | 15.1 | DD | 92 | 38 | Remember, analyze | 9.21 Ability to communicate in English and/or locally relevant languages; 10.24 plant and animal biology |

| 15.2 | 75 | |||||||

| 15.3 | 67 | |||||||

| 15.4 | 33 | |||||||

| 15.5 | 92 | |||||||

| C16. Combination herbal product quality analysis and risk | 0.5 | 16.1 | Cloze (FIB; DD) | 40 | 68 | Analyze, evaluate, remember | 9.21 Ability to communicate in English and/or locally relevant languages; 10.24 plant and animal biology; 10.35 toxicology | |

| 16.2 | 50 | |||||||

| Microscopic analysis | C17. Combination herbal product quality analysis | 0.4 | 17.1 | Cloze (FIB; DD) | 14 | 46 | Remember, analyze, evaluate | 9.21 Ability to communicate in English and/or locally relevant languages; 10.24 plant and animal biology; 10.34 pharmaceutical technology, including analyses of medicinal products |

| 17.2 | 23 |

| Student Performance and Examination Statistics | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Examinations | Total Student Attempts | Examination Duration [min] | Total Questions | Questions per Student Attempt | Student Average Performance [%] | Standard Deviation [%] | ||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 53 | 45 | 49 | 15 | 66.29 | 12.41 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 52 | 50 | 95 | 19 | 76.21 | 11.41 | ||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 53 | 55 | 47 | 17 | 65.88 | 11.64 | ||||||||||||||||

| Question types | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Examinations | TF | MC | DD | FIB | Essay | Cloze | ||||||||||||||||

| (MC) | (DD) | (MC; FIB) | (FIB) | (FIB; DD) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 27 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 0 | ||||||||||||

| 2 | 11 | 25 | 40 | 15 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||

| 3 | 0 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 16 | ||||||||||||

| Cognitive dimensions | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Examinations | Questions assessing low cognitive dimensions | Questions assessing high cognitive dimensions | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Remembering | Understanding | Applying | Analyzing | Evaluating | Creating | |||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 43 | 14 | 24 | 25 | 3 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 87 | 16 | 15 | 15 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 44 | 6 | 6 | 25 | 7 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Professional competencies | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Examinations | Ranked <60% by community pharmacists […] | Ranked >60% by community pharmacists […] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 7.6 | 10.24 | 10.28 | 11.38 | 11.39 | 7.2 | 7.3 | 7.4 | 7.5 | 7.7 | 9.21 | 10.27 | 10.29 | 10.30 | 10.31 | 10.32 | 10.33 | 10.34 | 10.35 | 10.37 | 13.46 | 17.63 | |

| 1 | 3 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 21 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 2 | 5 |

| 2 | 11 | 31 | 8 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 20 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 0 | 4 |

| 3 | 0 | 13 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 28 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 6 | 2 | 20 | 3 | 7 |

Appendix B

References

- Mortlock, R.; Lucas, C. Generative artificial intelligence (Gen-AI) in pharmacy education: Utilization and implications for academic integrity: A scoping review. Explor. Res. Clin. Soc. Pharm. 2024, 15, 100481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, C.M. AI-Assisted Exam Variant Generation: A Human-in-the-Loop Framework for Automatic Item Creation. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolovski, V.; Trajanov, D.; Chorbev, I. Advancing AI in Higher Education: A Comparative Study of Large Language Model-Based Agents for Exam Question Generation, Improvement, and Evaluation. Algorithms 2025, 18, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q. DeepSeek Hits Hard: Helping to Revolutionize Higher Education in the Era of Artificial Intelligence. Int. J. High. Educ. 2025, 14, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöhr, C.; Ou, A.W.; Malmström, H. Perceptions and usage of AI chatbots among students in higher education across genders, academic levels and fields of study. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2024, 7, 100259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, W.; Yuan, X.; Li, X.; Luo, W.; Xie, J.; Shi, B. Increasing acceptance of medical AI: The role of medical staff participation in AI development. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2023, 175, 105073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafson, K.A.; Berman, S.; Gavaza, P.; Mohamed, I.; Devraj, R.; Abdel Aziz, M.H.; Singh, D.; Southwood, R.; Ogunsanya, M.E.; Chu, A.; et al. Pharmacy faculty and students perceptions of artificial intelligence: A National Survey. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2025, 17, 102344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.; Sha, L.; Zhao, L.; Li, Y.; Martinez-Maldonado, R.; Chen, G.; Li, X.; Jin, Y.; Gašević, D. Practical and Ethical Challenges of Large Language Models in Education: A Systematic Scoping Review. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.13379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, S.; Pott, C.; Rutinowski, J.; Pauly, M.; Reining, C.; Kirchheim, A. Can ChatGPT Solve Undergraduate Exams from Warehousing Studies? An Investigation. Computers 2025, 14, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlert, A.; Ehlert, B.; Cao, B.; Morbitzer, K. Large Language Models and the North American Pharmacist Licensure Examination (NAPLEX) Practice Questions. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2024, 88, 101294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, V.; Donohoe, K.L.; Peddi, A.N.; Carr, E.; Kim, C.; Mele, V.; Patel, D.; Crawford, A.N. Artificial intelligence (AI) performance on pharmacy skills laboratory course assignments. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2025, 17, 102367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, S.K. Creating Large Language Model Resistant Exams: Guidelines and Strategies (Version 1). arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.12203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logullo, P.; De Beyer, J.A.; Kirtley, S.; Schlüssel, M.M.; Collins, G.S. Open access journal publication in health and medical research and open science: Benefits, challenges and limitations. BMJ Evid. Based Med. 2024, 29, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, H.D.; Kwon, S.; Linnebur, L.A.; Valdez, C.A.; Linnebur, S.A. Pharmacy student use of ChatGPT: A survey of students at a U.S. School of Pharmacy. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2024, 16, 102156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.F.; Danpanichkul, P.; Hayek, A.; Paul, E.; Farag, A.; Mansoor, M.; Thongprayoon, C.; Cheungpasitporn, W.; Othman, M.O. Artificial Intelligence in Gastroenterology Education: DeepSeek Passes the Gastroenterology Board Examination and Outperforms Legacy ChatGPT Models. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2025, ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapovalov, V.B.; Shapovalov, Y.B.; Bilyk, Z.I.; Megalinska, A.P.; Muzyka, I.O. The Google Lens analyzing quality: An analysis of the possibility to use in the educational process. Educ. Dimens. 2019, 1, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapovalov, Y.; Bilyk, Z.; Atamas, A.; Shapovalov, V.; Uchitel, A. The Potential of Using Google Expeditions and Google Lens Tools under STEM-education in Ukraine. Educ. Dimens. 2019, 51, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilyk, Z.; Shapovalov, Y.; Shapovalov, V.; Antonenko, P.; Zhadan, S.; Lytovchenko, D.; Megalinska, A. Features of Using Mobile Applications to Identify Plants and Google Lens During the Learning Process. In Proceedings of the 2nd Myroslav I. Zhaldak Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology—AET, Kyiv, Ukraine, 11–12 November 2023; pp. 688–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElKhalifa, D.; Hussein, O.; Hamid, A.; Al-Ziftawi, N.; Al-Hashimi, I.; Ibrahim, M.I.M. Curriculum, competency development, and assessment methods of MSc and PhD pharmacy programs: A scoping review. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aly, A.; Mraiche, F.; Maklad, E.; Ali, R.; El-Awaisi, A.; El Hajj, M.S.; Mukhalalati, B. Examining the perception of undergraduate pharmacy students towards their leadership competencies: A mixed-methods study. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, J.; Sánchez Pozo, A.; Rekkas, D.; Volmer, D.; Hirvonen, J.; Bozic, B.; Skowron, A.; Mircioiu, C.; Sandulovici, R.; Marcincal, A.; et al. Hospital and Community Pharmacists’ Perceptions of Which Competences Are Important for Their Practice. Pharmacy 2016, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamgir, A.N.M. Origin, Definition, Scope and Area, Subject Matter, Importance, and History of Development of Pharmacognosy. In Therapeutic Use of Medicinal Plants and Their Extracts: Volume 1; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 73, pp. 19–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhami, N. Trends in Pharmacognosy: A modern science of natural medicines. J. Herb. Med. 2013, 3, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, V.; Dhalwal, K.; Mahadik, K.R. Phcog Rev. Review Article Some issues related to pharmacognosy. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2008, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Cadena-Bautista, Á.; López-Ponce, F.F.; Ojeda-Trueba, S.L.; Sierra, G.; Bel-Enguix, G. Exploring the Behavior and Performance of Large Language Models: Can LLMs Infer Answers to Questions Involving Restricted Information? Information 2025, 16, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, G.; Kumarage, T.; Alghamdi, Z.; Liu, H. Can Knowledge Graphs Reduce Hallucinations in LLMs?: A Survey (Version 2). arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.07914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco Abellan, M.; Ginovart Gisbert, M. On How Moodle Quizzes Can Contribute to the Formative e-Assessment of First-Year Engineering Students in Mathematics Courses. RUSC Univ. Knowl. Soc. J. 2012, 9, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamady, S.; Mershad, K.; Jabakhanji, B. Multi-version interactive assessment through the integration of GeoGebra with Moodle. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1466128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, C.; Gheyi, R.; Ribeiro, M. Assessing the Capability of LLMs in Solving POSCOMP Questions (Version 1). arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.20338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Alyakin, A.; Alber, D.A.; Stryker, J.; Tong, A.P.S.; Sangwon, K.; Goff, N.; de la Paz, M.; Hernandez-Rovira, M.; Park, K.Y.; et al. It is Too Many Options: Pitfalls of Multiple-Choice Questions in Generative AI and Medical Education (Version 1). arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.13508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiz statistics report—MoodleDocs. 2024. Available online: https://docs.moodle.org/500/en/Quiz_statistics_report (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Quiz Report Statistics—MoodleDocs. 2022. Available online: https://docs.moodle.org/dev/Quiz_report_statistics (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Odoh, U.E.; Gurav, S.S.; Chukwuma, M.O. (Eds.) Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry: Principles, Techniques, and Clinical Applications, 1st ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, W.C. Trease and Evans Pharmacognosy, 16th ed.; Saunders/Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tofade, T.; Elsner, J.; Haines, S.T. Best Practice Strategies for Effective Use of Questions as a Teaching Tool. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2013, 77, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubinstein, R.Y.; Kroese, D.P. Simulation and the Monte Carlo Method, 1st ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, W. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. Python Sci. Conf. 2010, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan-Montero, Y.; De-Moya-Anegón, F.; Guerrero-Bote, V.P. SCImago Graphica: A new tool for exploring and visually communicating data. El Prof. De La Inf. 2022, 31, e310502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roustaei, N. Application and interpretation of linear-regression analysis. Med. Hypothesis Discov. Innov. Ophthalmol. 2024, 13, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Fu, J.; Hu, K. Evaluating the Performance of DeepSeek-R1 and DeepSeek-V3 Versus OpenAI Models in the Chinese National Medical Licensing Examination: Cross-Sectional Comparative Study. JMIR Med. Educ. 2025, 11, e73469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouzabata, A. Pharmacognosy: 150 Corrected and Annotated Multiple-Choice Questions and Course Summaries. 2018. Available online: https://books.google.bg/books?id=78NODwAAQBAJ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

| LLM | Examination 1 | Examination 2 | Examination 3 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Standard Deviation | Average | Standard Deviation | Average | Standard Deviation | |||||||

| Point | [%] | Point | [%] | Point | [%] | Point | [%] | Point | [%] | Point | [%] | |

| ChatGPT 4o | 2.51 | 50.2 | 0.26 | 5.2 | 3.13 | 62.6 | 0.33 | 6.6 | 3.45 | 69.0 | 0.16 | 3.2 |

| DeepSeek R1 | 1.86 | 37.2 | 0.16 | 3.2 | 2.31 | 46.2 | 0.28 | 5.6 | 3.08 | 61.6 | 0.23 | 4.6 |

| LLM | Examination 1 | Examination 2 | Examination 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disregarded Categories | Categories with no Correlation | Coefficient of Determination (r2) per Category | Disregarded Categories | Categories with no Correlation | Coefficient of Determination (r2) per Category | Disregarded Categories | Categories with no Correlation | Coefficient of Determination (r2) per Category | |

| ChatGPT 4o | C8 | C1 C4 C5 C11 C12 C14 C15 | C2 (0.6938) C3 (0.4391) C6 (0.3273) C7 (0.7229) C9 (0.5423) C10 (0.1089) C13 (0.5111) | C1 | C2 C6 C7 C8 C11 C12 C13 C14 C16 | C3 (0.9185) C4 (0.8193) C5 (0.2936) C9 (0.4717) C10 (0.9670) C15 (0.3466) C17 (0.4700) C18 (0.9370) C19 (0.1046) | C4 C5 C6 C7 C8 C10 C11 C13 C14 C16 C17 | C1 C12 | C2 (0.9494) C3 (0.1120) C9 (02161) C15 (0.1684) |

| DeepSeek R1 | C8 | C1 C4 C5 C6 C10 C13 C14 C15 | C2 (0.2521) C3 (0.1007) C7 (0.9521) C9 (0.5423) C11 (0.9912) C12 (0.2500) | C1 | C2 C5 C6 C8 C9 C11 C12 C13 C17 | C3 (0.9185) C4 (0.3530) C7 (0.8781) C10 (0.2370) C14 (0.2365) C15 (0.4014) C16 (0.6792) C18 (0.4918) C19 (09075) | C4 C5 C6 C7 C8 C10 C11 C13 C14 C16 C17 | C1 C3 C9 C12 C15 | C2 (0.4652) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stoyanov, A.; Nedelcheva, A. Identifying Features of LLM-Resistant Exam Questions: Insights from Artificial Intelligence (AI)–Student Performance Comparisons. Sci 2025, 7, 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040183

Stoyanov A, Nedelcheva A. Identifying Features of LLM-Resistant Exam Questions: Insights from Artificial Intelligence (AI)–Student Performance Comparisons. Sci. 2025; 7(4):183. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040183

Chicago/Turabian StyleStoyanov, Asen, and Anely Nedelcheva. 2025. "Identifying Features of LLM-Resistant Exam Questions: Insights from Artificial Intelligence (AI)–Student Performance Comparisons" Sci 7, no. 4: 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040183

APA StyleStoyanov, A., & Nedelcheva, A. (2025). Identifying Features of LLM-Resistant Exam Questions: Insights from Artificial Intelligence (AI)–Student Performance Comparisons. Sci, 7(4), 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040183