Implementation and Applications of a Precision Weak-Field Sample Environment for Polarized Neutron Reflectometry at J-PARC

Abstract

1. Introduction

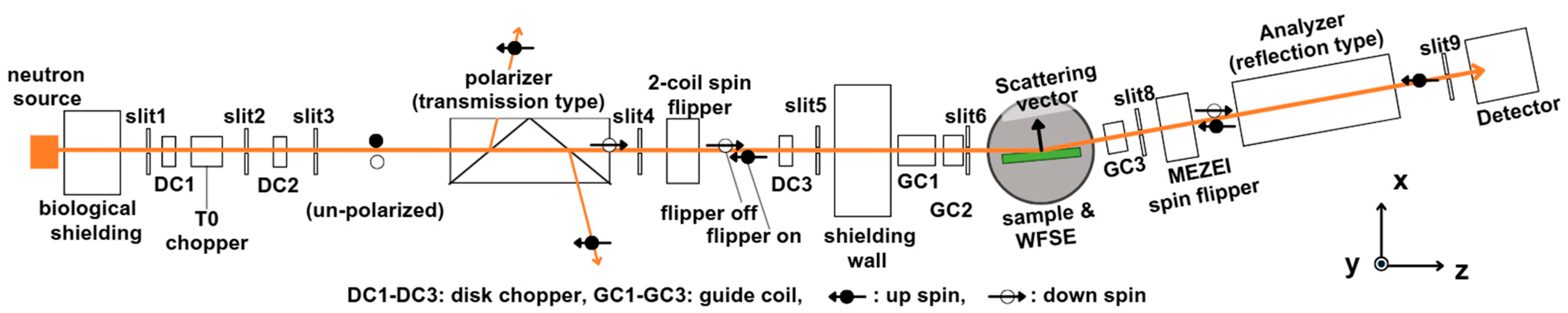

2. Instrumentation

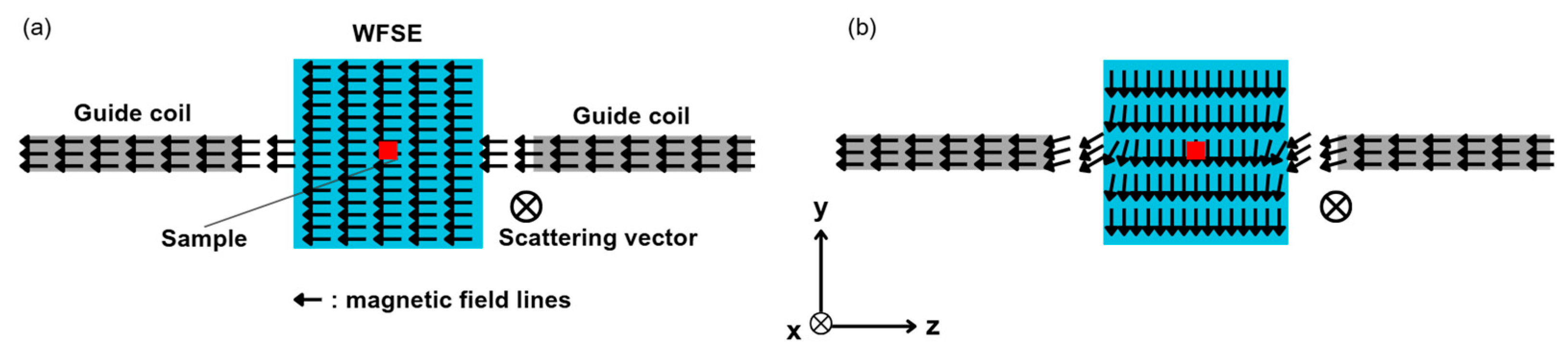

2.1. Design and Performance of the Precision WFSE

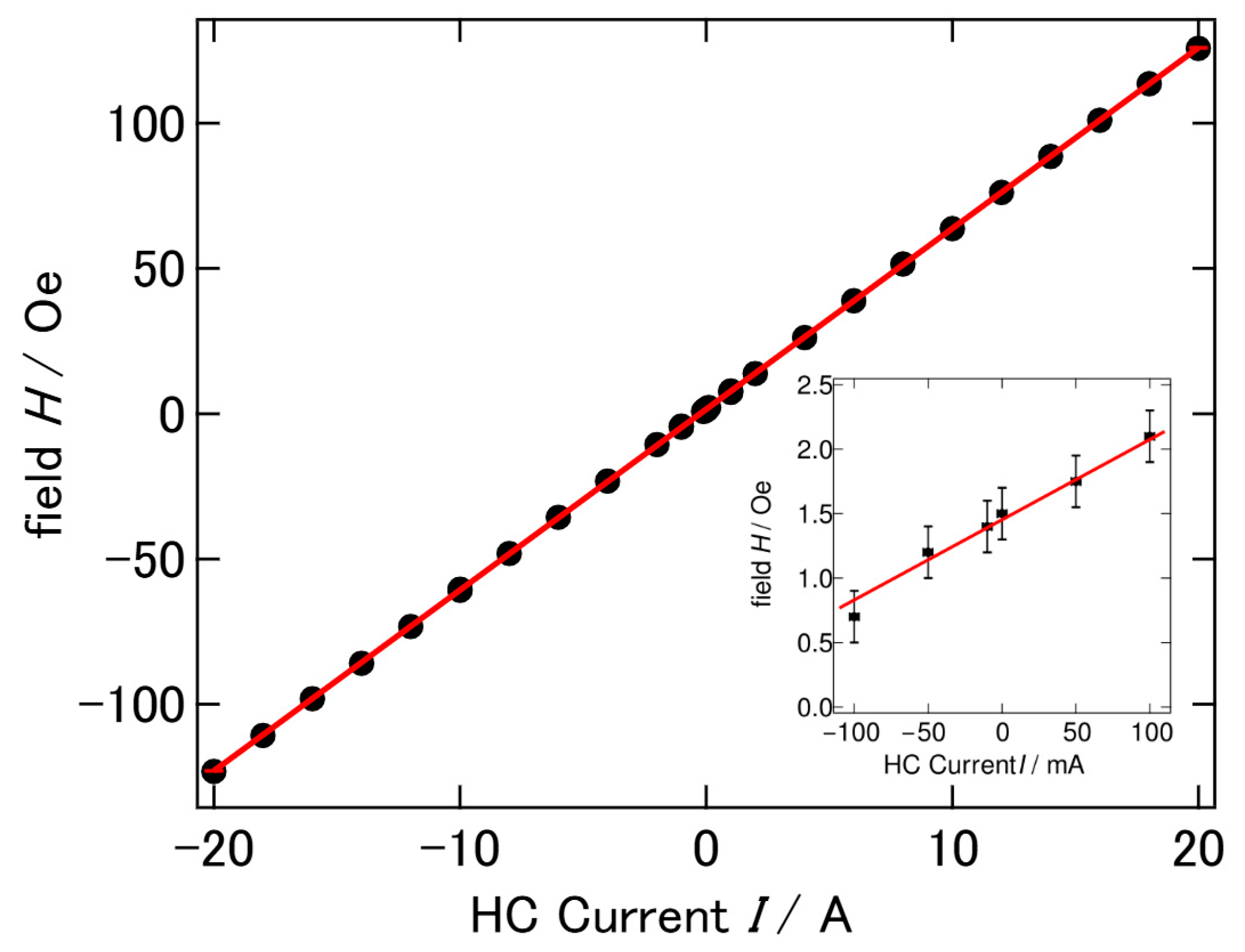

2.2. Magnetic-Field Characteristics and Polarization Efficiencies

3. Applications

3.1. PNR on Fe Thin Film in the Remanent State

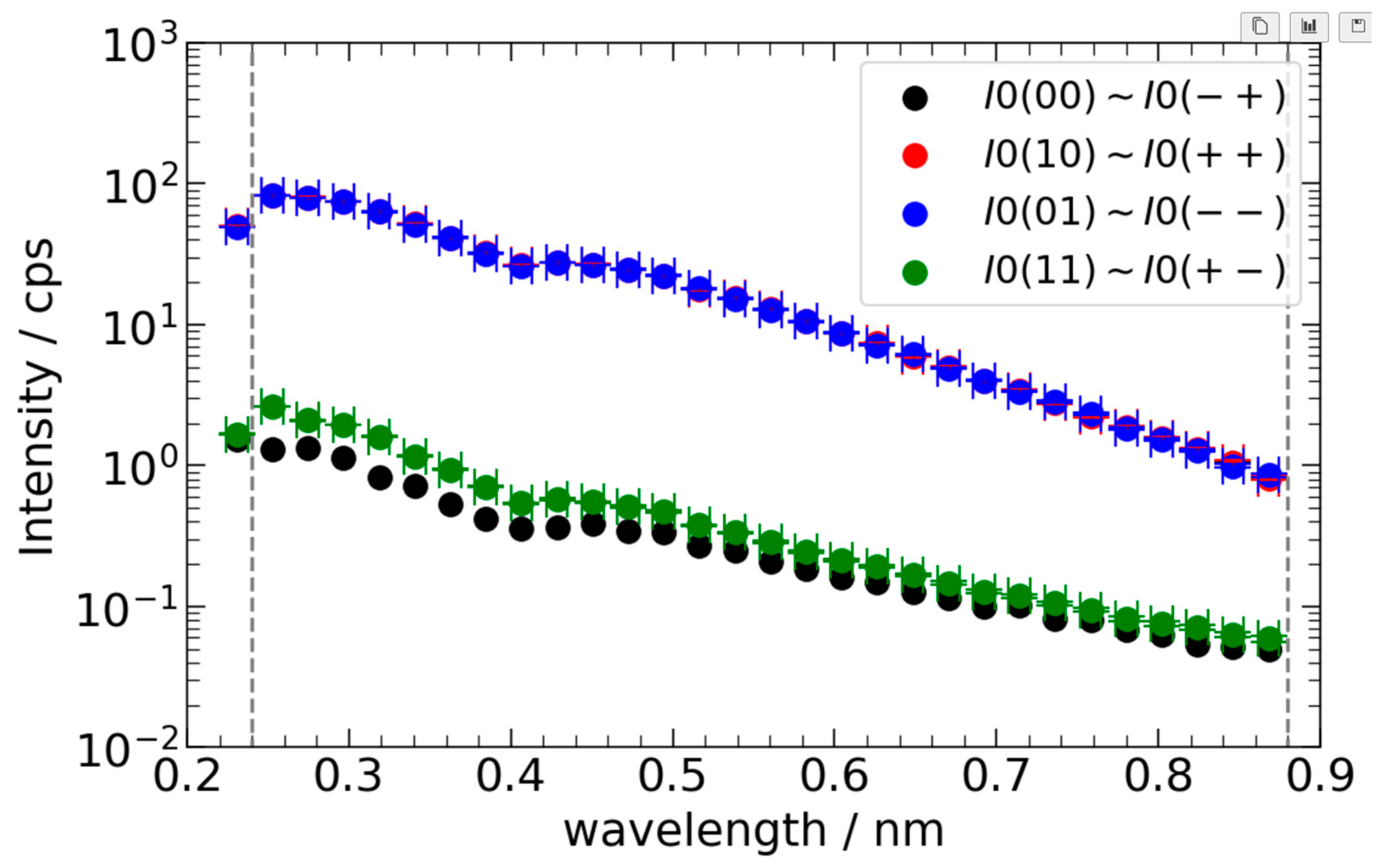

3.1.1. Method

3.1.2. Analysis and Results for Fe Thin Film in the Remanent State

3.2. Structural Analysis of Cellulose Acetate (CA) Film with Substantial Surface Roughness Using Magnetic Contrast Variation PNR (MCV-PNR)

3.2.1. MCV-PNR Method

3.2.2. Analysis and Results Using MCV-PNR

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Itoh, S.; Fukumura, S.; Fujiie, T.; Kitaguchi, M.; Shimizu, H.M. Demonstration of Simultaneous Measurement of the Spin Rotation of Dynamically-Diffracted Neutrons from Multiple Crystal Planes Using Pulsed Neutrons. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A 2023, 1057, 168734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, R.; Ishikawa, R.; Akutsu-Suyama, K.; Nakanishi, R.; Tomohiro, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Iida, K.; Mitome, M.; Hasegawa, S.; Kuroda, S. Direct Probe of the Ferromagnetic Proximity Effect at the Interface of SnTe/Fe Heterostructure by Polarized Neutron Reflectometry. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 8228–8235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amemiya, K.; Sakamaki, M.; Mizusawa, M.; Takeda, M. Twisted Magnetic Structure in Ferromagnetic Ultrathin Ni Films Induced by Magnetic Anisotropy Interaction with Antiferromagnetic FeMn. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 89, 054404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtsuka, Y.; Kanazawa, N.; Hirayama, M.; Matsui, A.; Nomoto, T.; Arita, R.; Nakajima, T.; Hanashima, T.; Ukleev, V.; Aoki, H.; et al. Emergence of Spin-Orbit Coupled Ferromagnetic Surface State Derived from Zak Phase in a Nonmagnetic Insulator FeSi. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabj0498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagashima, G.; Kurokawa, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Horiike, S.; Schönke, D.; Krautscheid, P.; Reeve, R.; Kläui, M.; Inagaki, Y.; Kawae, T.; et al. Quasi-Antiferromagnetic Multilayer Stacks with 90 Degree Coupling Mediated by Thin Fe Oxide Spacers. J. Appl. Phys. 2019, 126, 093901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Kurokawa, Y.; Nagashima, G.; Horiike, S.; Hanashima, T.; Schönke, D.; Krautscheid, P.; Reeve, R.M.; Kläui, M.; Yuasa, H. Determination of Fine Magnetic Structure of Magnetic Multilayer with Quasi Antiferromagnetic Layer by Using Polarized Neutron Reflectivity Analysis. AIP Adv. 2020, 10, 015323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, R.; Yamazaki, D.; Aoki, H.; Akutsu-Suyama, K.; Hanashima, T.; Miyata, N.; Soyama, K.; Bigault, T.; Saerbeck, T.; Courtois, P. Improved Performance of Wide Bandwidth Neutron-Spin Polarizer Due to Ferromagnetic Interlayer Exchange Coupling. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 130, 083904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubayer, A. Enhanced Polarizing Neutron Optics with 11B4C Incorporation: SLD Tunability, Interface Refinement, and Elimination of Magnetic Coercivity. Licentiate Thesis, Comprehensive Summary. Linköping University Electronic Press, Linköping, Sweden, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Grünberg, P.; Schreiber, R.; Pang, Y.; Brodsky, M.B.; Sowers, H. Layered Magnetic Structures: Evidence for Antiferromagnetic Coupling of Fe Layers across Cr Interlayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1986, 57, 2442–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spezzani, C.; Torelli, P.; Sacchi, M.; Delaunay, R.; Hague, C.F.; Salmassi, F.; Gullikson, E.M. Hysteresis Curves of Ferromagnetic and Antiferromagnetic Order in Metallic Multilayers by Resonant X-Ray Scattering. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 66, 052408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.T.; Zhou, W.; Kirby, B.J.; Poon, S.J. Interfacial Mixing Effect in a Promising Skyrmionic Material: Ferrimagnetic Mn4N. AIP Adv. 2022, 12, 085023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moubah, R.; Magnus, F.; Warnatz, T.; Palsson, G.K.; Kapaklis, V.; Ukleev, V.; Devishvili, A.; Palisaitis, J.; Persson, P.O.Å.; Hjörvarsson, B. Discrete Layer-by-Layer Magnetic Switching in Fe/MgO (001) Superlattices. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2016, 5, 044011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rashid, M.M.; Bhattacharya, D.; Grutter, A.; Kirby, B.; Atulasimha, J. Polarized Neutron Reflectometry Study of Depth Dependent Magnetization Variation in Co Thin Film Due to Strain Transfer from PMN-PT Substrate. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 124, 113903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, J.D.; Kirby, B.J.; Kwon, J.; Fabbris, G.; Meyers, D.; Freeland, J.W.; Martin, I.; Heinonen, O.G.; Steadman, P.; Zhou, H.; et al. Oscillatory Noncollinear Magnetism Induced by Interfacial Charge Transfer in Superlattices Composed of Metallic Oxides. Phys. Rev. X 2016, 6, 041038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenwalla, S.; Felcher, G.P.; Fullerton, E.E.; Bader, S.D. Polarized-Neutron-Reflectivity Confirmation of 90° Magnetic Structure in Fe/Cr(001) Superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 53, 2474–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Schreyer, A.; Ankner, J.F.; Zeidler, T.; Zabel, H.; Majkrzak, C.F.; Schäfer, M.; Grünberg, P. Direct Observation of Non-Collinear Spin Structures in Fe/Cr(001) Superlattices. Europhys. Lett. 1995, 32, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukleev, V.; Ajejas, F.; Devishvili, A.; Vorobiev, A.; Steinke, N.-J.; Cubitt, R.; Luo, C.; Abrudan, R.-M.; Radu, F.; Cros, V.; et al. Observation by SANS and PNR of Pure Néel-Type Domain Wall Profiles and Skyrmion Suppression below Room Temperature in Magnetic [Pt/CoFeB/Ru]10 Multilayers. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2024, 25, 2315015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostylev, M.; Causer, G.L.; Lambert, C.-H.; Schefer, T.; Weiss, C.; Callori, S.J.; Salahuddin, S.; Wang, X.L.; Klose, F. In Situ Ferromagnetic Resonance Capability on a Polarized Neutron Reflectometry Beamline. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2018, 51, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sears, V.F. Neutron Scattering Lengths and Cross Sections. Neutron News 1992, 3, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubayer, A.; Eriksson, F.; Ghafoor, N.; Stahn, J.; Birch, J.; Glavic, A. Optimization of Magnetic Contrast Layer for Neutron Reflectometry. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2025, 55, 1299–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, M.; Yamazaki, D.; Soyama, K.; Maruyama, R.; Hayashida, H.; Asaoka, H.; Yamazaki, T.; Kubota, M.; Aizawa, K.; Arai, M.; et al. Current Status of a New Polarized Neutron Reflectometer at the Intense Pulsed Neutron Source of the Materials and Life Science Experimental Facility (MLF) of J-PARC. Chin. J. Phys. 2012, 50, 161. [Google Scholar]

- Kai, T.; Harada, M.; Teshigawara, M.; Watanabe, N.; Kiyanagi, Y.; Ikeda, Y. Neutronic Performance of Rectangular and Cylindrical Coupled Hydrogen Moderators in Wide-Angle Beam Extraction of Low-Energy Neutrons. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A 2005, 550, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, K.; Kawakita, Y.; Itoh, S.; Abe, J.; Aizawa, K.; Aoki, H.; Endo, H.; Fujita, M.; Funakoshi, K.; Gong, W.; et al. Materials and Life Science Experimental Facility (MLF) at the Japan Proton Accelerator Research Complex II: Neutron Scattering Instruments. Quantum Beam Sci. 2017, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, K.; Nakamura, T.; Sakasai, K.; Soyama, K.; Yamagishi, H. Performance Evaluation of High-Pressure MWPC with Individual Line Readout under Cf-252 Neutron Irradiation. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2014, 528, 012045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaud, P.; Steinberg, R.I.; Vignon, B. A Two-Coil Spin Flipper for Beams of Polarized Slow Neutrons. Nucl. Instrum. Methods 1975, 125, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayter, J.B. Matrix Analysis of Neutron Spin-Echo. Z. Phys. B Condens. Matter 1978, 31, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatani, T.; Inamura, Y.; Moriyama, K.; Ito, T. IROHA2: Standard Instrument Control Software Framework in MLF, J-PARC. In Proceedings of the 11th New Opportunities for Better User Group Software, Copenhagen, Denmark, 17–19 October 2016; Volume 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inamura, Y.; Nakatani, T.; Suzuki, J.; Otomo, T. Development Status of Software “Utsusemi” for Chopper Spectrometers at MLF, J-PARC. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2013, 82, SA031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavic, A.; Björck, M. GenX 3: The Latest Generation of an Established Tool. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2022, 55, 1063–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, J.; Garvey, C.J.; Holt, S.; Tabor, R.F.; Winther-Jensen, B.; Batchelor, W.; Garnier, G. Adsorption of Cationic Polyacrylamide at the Cellulose–Liquid Interface: A Neutron Reflectometry Study. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 448, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, A. Co-Refinement of Multiple-Contrast Neutron/X-Ray Reflectivity Data Using MOTOFIT. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2006, 39, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A. Motofit—Integrating Neutron Reflectometry Acquisition, Reduction and Analysis into One, Easy to Use, Package. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2010, 251, 012094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, R. Oxford School on Neutron Scattering. In Proceedings of the Lecture Notes of 12th Oxford School on Neutron Scatter-ing, Oxford, UK, 5–16 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hiroi, K.; Shinohara, T.; Hayashida, H.; Parker, J.D.; Oikawa, K.; Harada, M.; Su, Y.; Kai, T. Magnetic Field Imaging of a Model Electric Motor Using Polarized Pulsed Neutrons at J-PARC/MLF. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 862, 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, T.; Hiroi, K.; Su, Y.; Kai, T.; Nakatani, T.; Oikawa, K.; Segawa, M.; Hayashida, H.; Parker, J.D.; Matsumoto, Y.; et al. Polarization Analysis for Magnetic Field Imaging at RADEN in J-PARC/MLF. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 862, 012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildes, A.R. The Polarizer-Analyzer Correction Problem in Neutron Polarization Analysis Experiments. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 1999, 70, 4241–4245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saerbeck, T.; Klose, F.; Le Brun, A.P.; Füzi, J.; Brule, A.; Nelson, A.; Holt, S.A.; James, M. Invited Article: Polarization “Down Under”: The Polarized Time-of-Flight Neutron Reflectometer PLATYPUS. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2012, 83, 081301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeda, M.; (JAEA, Kashiwa, Japan). Private Communication, 2023.

| Upstream Flipper | Downstream Flipper | I(ij) | Corrected Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|

| off (0) | off (0) | I0(00), I(00) | I0−+, R−+ |

| off (0) | on (1) | I0(01), I(01) | I0−−, R−− |

| on (1) | off (0) | I0(10), I(10) | I0++, R++ |

| on (1) | on (1) | I0(11), I(11) | I0−+, R−+ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hanashima, T.; Akutsu-Suyama, K.; Ohe, Y.; Kasai, S.; Kira, H.; Hattori, A.N.; Osaka, A.I.; Tanaka, H.; Suzuki, J.-I.; Kakurai, K. Implementation and Applications of a Precision Weak-Field Sample Environment for Polarized Neutron Reflectometry at J-PARC. Quantum Beam Sci. 2025, 9, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/qubs9040035

Hanashima T, Akutsu-Suyama K, Ohe Y, Kasai S, Kira H, Hattori AN, Osaka AI, Tanaka H, Suzuki J-I, Kakurai K. Implementation and Applications of a Precision Weak-Field Sample Environment for Polarized Neutron Reflectometry at J-PARC. Quantum Beam Science. 2025; 9(4):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/qubs9040035

Chicago/Turabian StyleHanashima, Takayasu, Kazuhiro Akutsu-Suyama, Yoshimasa Ohe, Satoshi Kasai, Hiroshi Kira, Azusa N. Hattori, Ai I. Osaka, Hidekazu Tanaka, Jun-Ichi Suzuki, and Kazuhisa Kakurai. 2025. "Implementation and Applications of a Precision Weak-Field Sample Environment for Polarized Neutron Reflectometry at J-PARC" Quantum Beam Science 9, no. 4: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/qubs9040035

APA StyleHanashima, T., Akutsu-Suyama, K., Ohe, Y., Kasai, S., Kira, H., Hattori, A. N., Osaka, A. I., Tanaka, H., Suzuki, J.-I., & Kakurai, K. (2025). Implementation and Applications of a Precision Weak-Field Sample Environment for Polarized Neutron Reflectometry at J-PARC. Quantum Beam Science, 9(4), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/qubs9040035