Temporal Variation in Nano-Enhanced Laser-Induced Plasma Spectroscopy (NELIPS)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Setup and Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

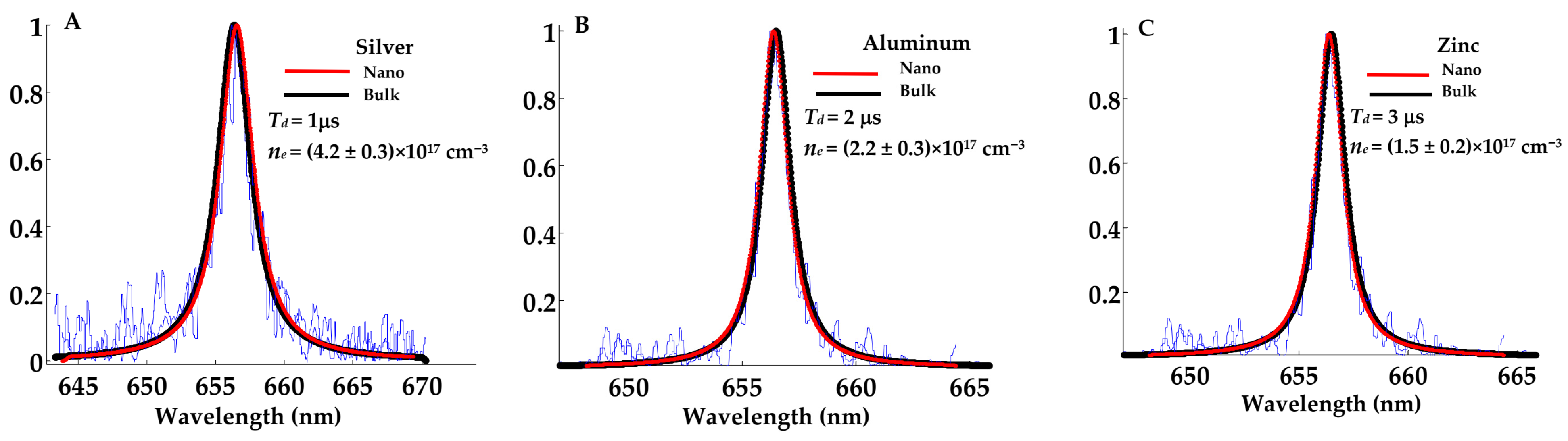

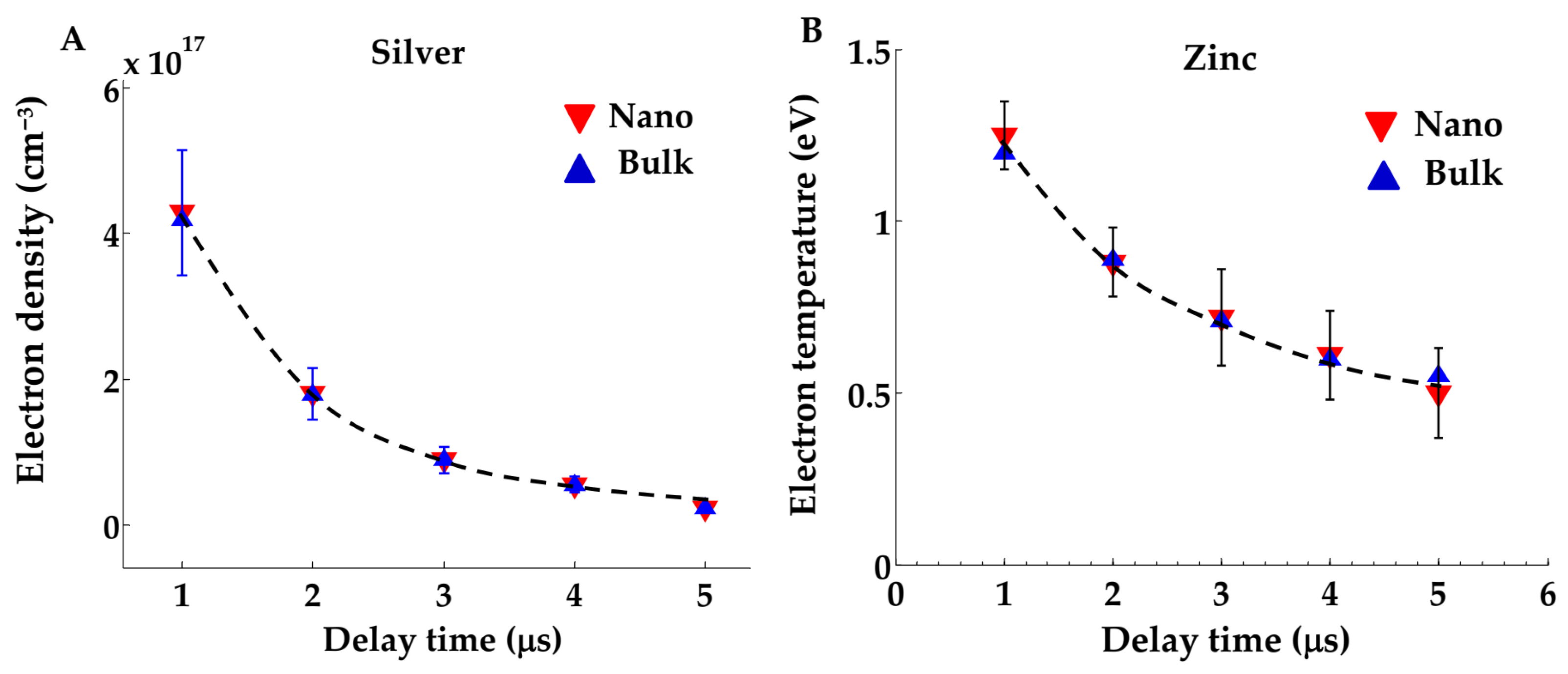

3.1. Measurement of Plasma Electron Density and Temperature

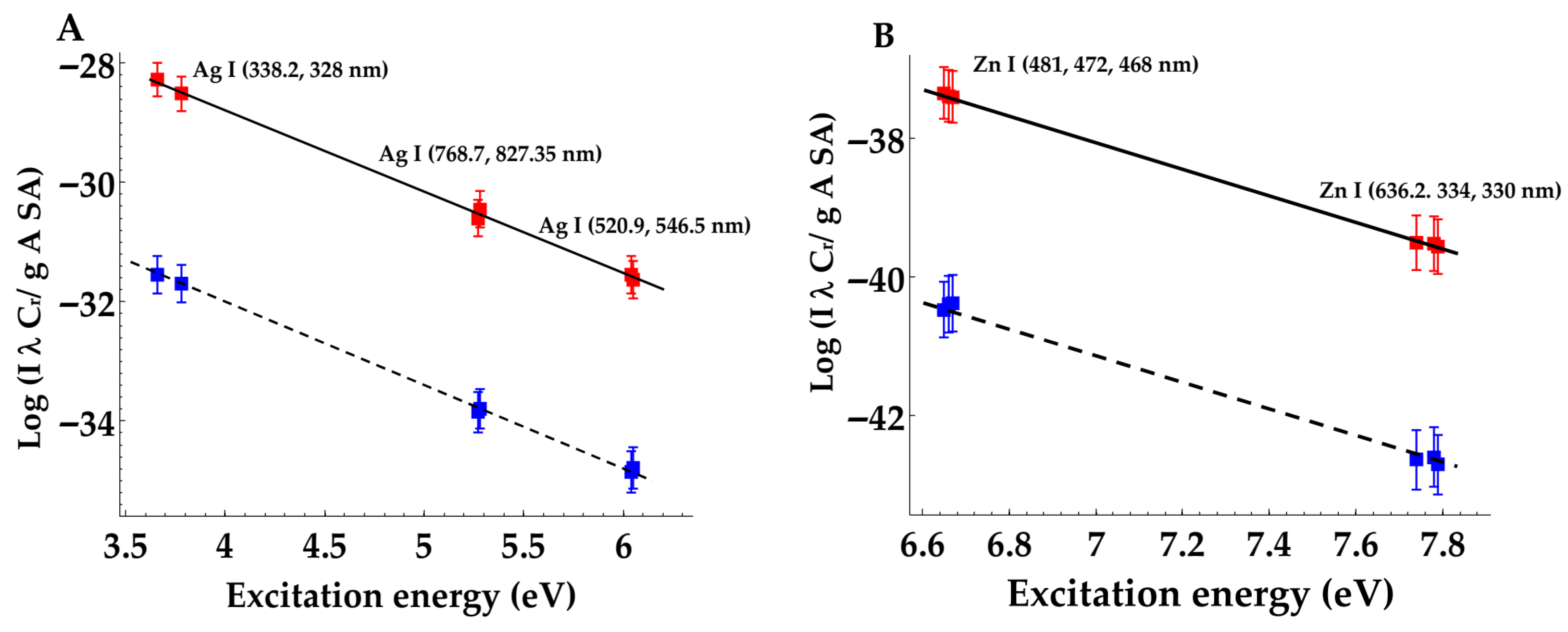

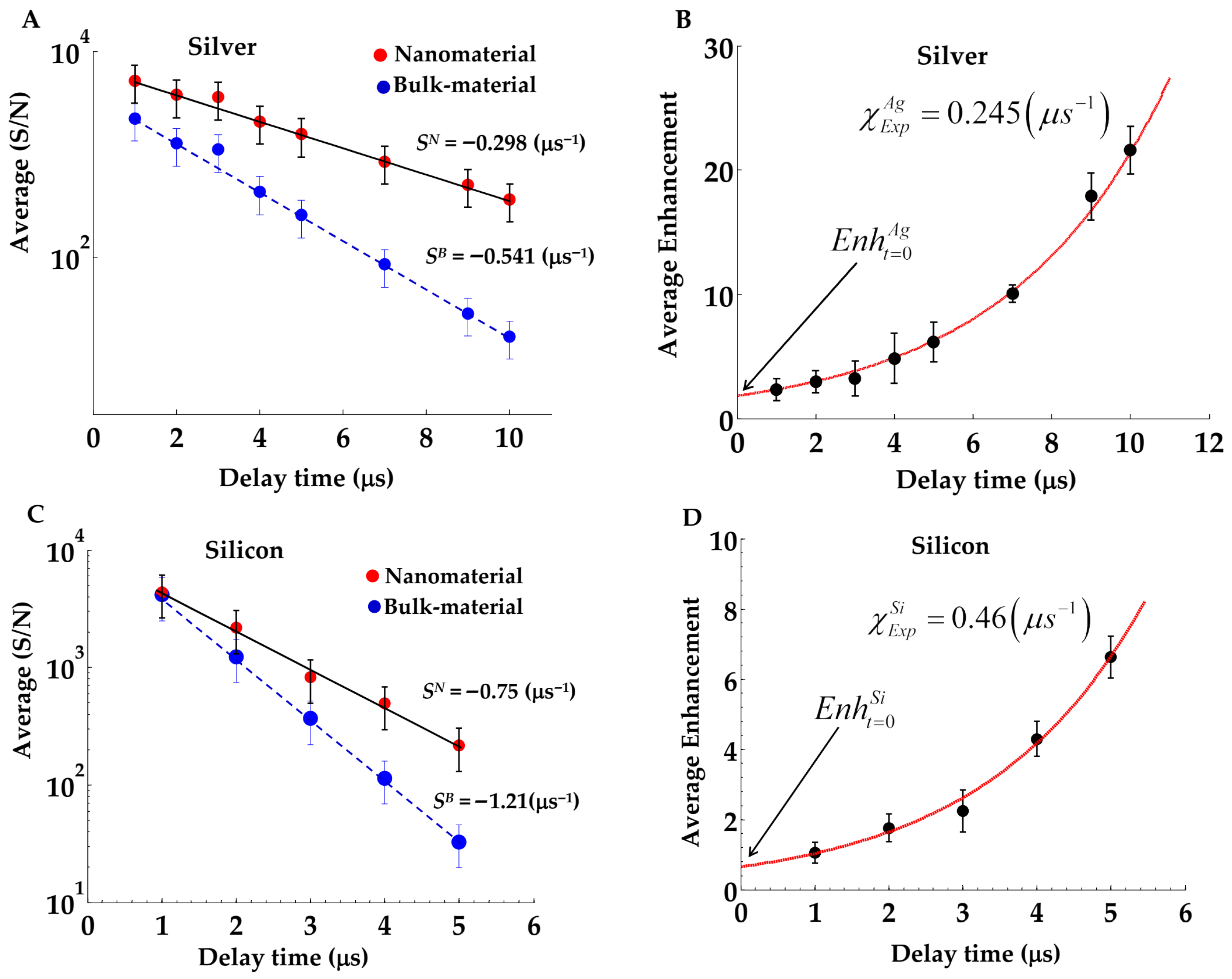

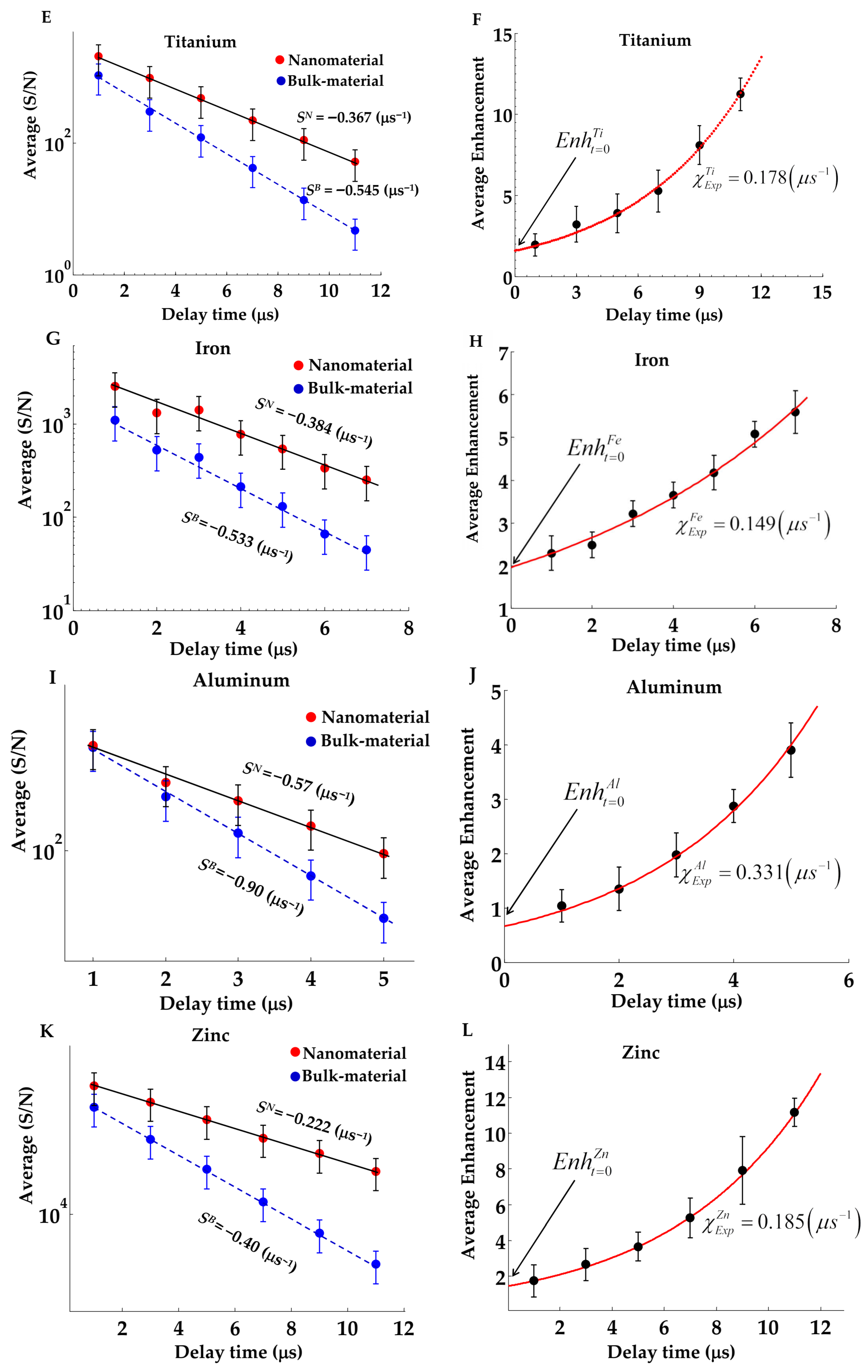

3.2. Measurement of Average Enhancement over Different Wavelengths

- (a)

- Silver: Ag I—lines at wavelengths 328.02, 338.2, 520.9, 546.5, 768.7 and 827.3 nm;

- (b)

- Zinc: Zn I—lines at wavelength 330.29, 334.55, 468.2, 472.2, 481.01, and 636.38 nm;

- (c)

- Aluminum: Al I—lines at wavelengths 308.2, 309.3, 394.8, 396.15 nm;

- (d)

- Silicon: Si I—lines at wavelengths 288.15, 390.55 nm.

3.3. Modeling of the Temporal Variation in Enhanced Emission NELIPS

4. Conclusions

- (a)

- Why does this happen when pure nanomaterials are irradiated by pulsed lasers?

- (b)

- Could this enhanced emission happen if one induces plasma from pure nanomaterials by a different excitation method, e.g., inductively coupled plasma (ICP) or by arc discharge?

- (c)

- Is this enhanced emission an inherent property of the nanomaterials’ class of matter?

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Measured Electron Density (×1017 cm−3) with Associated Error Margins | ||||||||||

| Delay | 1 μs | 2 μs | 3 μs | 4 μs | 5 μs | |||||

| Element | Nano | Bulk | Nano | Bulk | Nano | Bulk | Nano | Bulk | Nano | Bulk |

| Ag | 4.29 ± 0.1 | 4.2 ± 0.08 | 1.8 ± 0.12 | 1.79 ± 0.10 | 0.89 ± 0 0.04 | 0.89 ± 0.03 | 0.55 ± 0.15 | 0.55 ± 0.13 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 0.23 ± 0.05 |

| Zn | 4.4 ± 0.66 | 4.7 ± 0.70 | 2.5 ± 0.90 | 2.4 ± 0.80 | 1.2 ± 0.40 | 1.4 ± 0.50 | 0.7 ± 0.26 | 0.70 ± 0.24 | 0.64 ± 0.08 | 0.54 ± 0.07 |

| Si | 4.37 ± 0.8 | 4.1 ± 0.50 | 1.5 ± 0.09 | 1.45 ± 0.09 | 0.78 ± 0.07 | 0.77 ± 0.08 | 0.42 ± 0.08 | 0.45 ± 0.07 | 0.37 ± 0.02 | 0.34 ± 0.05 |

| Al | 4.6 ± 0.66 | 4.7 ± 0.70 | 2.2 ± 0.90 | 2.3 ± 0.80 | 1.2 ± 0.40 | 1.1 ± 0.50 | 0.69 ± 0.26 | 0.68 ± 0.24 | 0.54 ± 0.08 | 0.54 ± 0.07 |

| Fe | 4.42 ± 0.8 | 4.8 ± 0.50 | 1.47 ± 0.09 | 1.46 ± 0.09 | 0.83 ± 0.07 | 0.77 ± 0.08 | 0.42 ± 0.08 | 0.43 ± 0.07 | 0.35 ± 0.02 | 0.33 ± 0.05 |

| Ti | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 3.4 ± 0.03 | 1.8 ± 0.08 | 1.7 ± 0.03 | 0.99 ± 0.05 | 0.91 ± 0.04 | 0.72 ± 0.07 | 0.69 ± 0.02 | 0.52 ± 0.04 | 0.54 ± 0.03 |

| Measured Electron Temperatures (eV) with Associated Error Margins | ||||||||||

| Delay | 1 μs | 2 μs | 3 μs | 4 μs | 5 μs | |||||

| Element | Nano | Bulk | Nano | Bulk | Nano | Bulk | Nano | Bulk | Nano | Bulk |

| Ag | 1.12 ± 0.1 | 1.06 ± 0.09 | 0.89 ± 0.08 | 0.89 ± 0.06 | 0.72 ± 0.05 | 0.72 ± 0.07 | 0.63 ± 0.07 | 0.60 ± 0.02 | 0.54 ± 0.04 | 0.55 ± 0.06 |

| Zn | 1.25 ± 0.24 | 1.2 ± 0.21 | 0.88 ± 0.14 | 0.89 ± 0.11 | 0.72 ± 0.09 | 0.71 ± 0.08 | 0.61 ± 0.07 | 0.60 ± 0.05 | 0.50 ± 0.05 | 0.55 ± 0.06 |

| Al | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.02 ± 0.09 | 0.89 ± 0.08 | 0.89 ± 0.06 | 0.72 ± 0.05 | 0.72 ± 0.07 | 0.63 ± 0.07 | 0.60 ± 0.02 | 0.53 ± 0.04 | 0.55 ± 0.06 |

| Si | 1.05 ± 0.24 | 1.2 ± 0.21 | 0.88 ± 0.14 | 0.89 ± 0.11 | 0.72 ± 0.09 | 0.71 ± 0.08 | 0.61 ± 0.07 | 0.60 ± 0.05 | 0.50 ± 0.05 | 0.51 ± 0.06 |

Appendix C

- 1.

- Using the standard NELIPS experimental setup.

- 2.

- Measure the laser spot size area at the target position in the units of cm2 and measure laser energy per laser shot (in units Joule), then determine the laser fluence in the units of (J/cm2).

- 3.

- Start with irradiating bulk material and record the plasma emission spectrum.

- 4.

- Decrease the laser fluence by nearly equal steps (via introducing neutral density filters in the laser beam path) and repeat the previous step until no appreciable optical signal is recorded.

- 5.

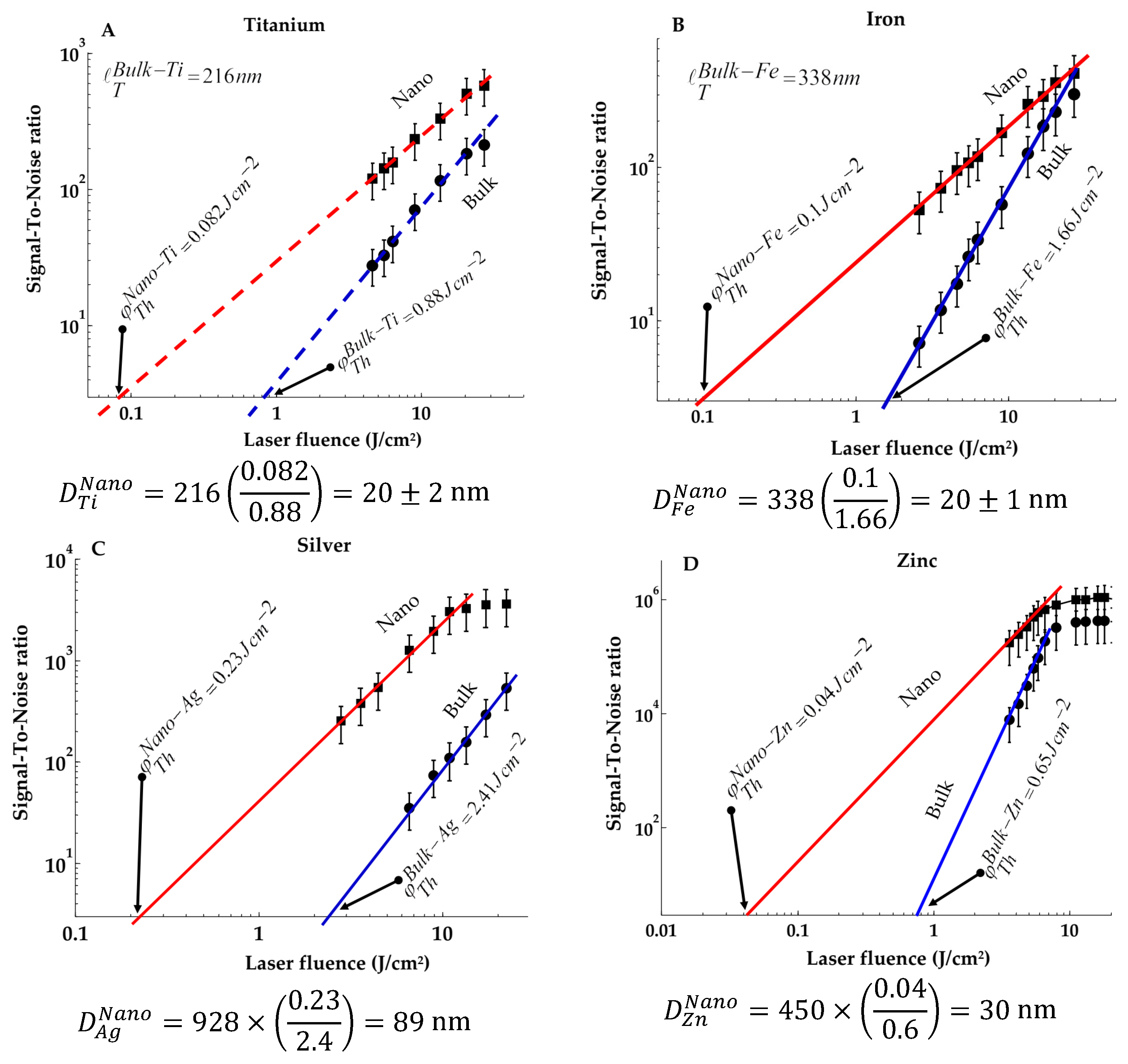

- Plot the relation between laser fluence and the spectral intensity (Signal-To-Noise) S/N ratio of one of the prominent spectral lines, e.g., the emission at wavelength of 480 nm is suitable for zinc (presented on form of bulk and nanomaterial), while wavelength at 520.9 nm is suitable for silver.

- 6.

- Under typical experimental conditions, one should repeat the previous procedures for the corresponding nanomaterial.

- 7.

- Measure the plasma ignition thresholds of both bulk and nanomaterial as shown in Figure A1 at the point of intersection of the backward extrapolation with the horizontal axis at S/N = 3. One must notice that .

- 8.

- With the help of the available standard data tables, find the numerical values of the following thermal quantities of the bulk material in SI units as given in Table A1, which presents the coefficient of thermal conductivity, density and isochoric heat capacity of the bulk materials, respectively.

- 9.

- With basic knowledge of the laser pulse duration time , one can calculate the thermal diffusion (or conduction) length of the bulk material using the well-known expression [34] .

- 10.

- Utilizing one of the important outcomes of the recently established principle of the NELIPS approach, i.e., if one can measure the laser-induced plasma ignition threshold fluence of a bulk material and for the corresponding nano material , the following expression can be held expressing the relation of the diameter of the nanoparticles with thermal conduction length [34], .

| Material | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Titanium | 22 | 4500 | 523 | 216 |

| Iron | 80 | 7870 | 444 | 338 |

| Silver | 429 | 10,500 | 237 | 928 |

| Zinc | 111 | 7133 | 383 | 450 |

References

- Kunze, H.-J. Introduction to Plasma Spectroscopy; Springer Series on Atomic, Optical, and Plasma Physics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; ISBN 9783642022326. [Google Scholar]

- Griem, H.R. Principles of Plasma Spectroscopy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997; 366p, ISBN 9780511524578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremers, D.A.; Radziemski, L.J. Handbook of Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy, 1st ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, T. Plasma Spectroscopy; Oxford Scientific Publications: Oxford, UK, 2004; ISBN 0-19-853028-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherbini, A.E.; Aboulfotouh, A.; Sherbini, T.E. On the Similarity and Differences Between Nano-Enhanced Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy and Nano-Enhanced Laser-Induced Plasma Spectroscopy in Laser-Induced Nanomaterials Plasma. QuBS 2024, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, D.W.; Omenetto, N. Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS), Part II: Review of Instrumental and Methodological Approaches to Material Analysis and Applications to Different Fields. Appl. Spectrosc. 2012, 66, 347–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes Andrade, D.; Pereira-Filho, E.R.; Amarasiriwardena, D. Current Trends in Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy: A Tutorial Review. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2021, 56, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villas-Boas, P.R.; Franco, M.A.; Martin-Neto, L.; Gollany, H.T.; Milori, D.M.B.P. Applications of Laser-induced Breakdown Spectroscopy for Soil Characterization, Part II: Review of Elemental Analysis and Soil Classification. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2020, 71, 805–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallé, B.; Cremers, D.A.; Maurice, S.; Wiens, R.C.; Fichet, P. Evaluation of a Compact Spectrograph for In-Situ and Stand-off Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy Analyses of Geological Samples on Mars Missions. Spectrochim. Acta B At. Spectrosc. 2005, 60, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangoni, B.S.; Nicolodelli, G.; Senesi, G.S.; Fonseca, N.; Izario Filho, H.J.; Xavier, A.A.; Villas-Boas, P.R.; Milori, D.M.B.P.; Menegatti, C.R. Multi-Elemental Analysis of Landfill Leachates by Single and Double Pulse Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy. Microchem. J. 2021, 165, 106125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitelli, M.; Casavola, A.; Colonna, G.; De Giacomo, A. Laser-Induced Plasma Expansion: Theoretical and Experimental Aspects. Spectrochim. Acta B At. Spectrosc. 2004, 59, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konjević, N.; Ivković, M.; Jovićević, S. Spectroscopic Diagnostics of Laser-Induced Plasmas. Spectrochim. Acta B At. Spectrosc. 2010, 65, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, T.A.; Nagayama, T.; Cho, P.B.; Kilcrease, D.P.; Fontes, C.J.; Zammit, M.C. Introduction to Spectral Line Shape Theory. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2022, 55, 034002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorge, S.; Günter, S. Simulation of Shifted and Asymmetric Hydrogen Line Profiles. Eur. Phys. J. D 2000, 12, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, N.M.; Haider, Z.; Tufail, K.; Ismail, F.D.; Ali, J. Spectroscopic Diagnostics of Laser Induced Plasma and Self-Absorption Effects in Al Lines. Phys. Plasmas 2018, 25, 073303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sherbini, A.M.; El Farash, A.H.; El Sherbini, T.M.; Parigger, C.G. Opacity Corrections for Resonance Silver Lines in Nano-Material Laser-Induced Plasma. Atoms 2019, 7, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, J.A.; Aragón, C. New Procedure for CSigma Laser Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy Addressing the Laser-Induced Plasma Inhomogeneity. Spectrochim. Acta B At. Spectrosc. 2024, 217, 106969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherbini, A.M.E.; Aboulfotouh, A.-N.M.; Rashid, F.F.; Allam, S.H.; Dakrouri, A.E.; Sherbini, T.M.E. Observed Enhancement in LIBS Signals from Nano vs. Bulk ZnO Targets: Comparative Study of Plasma Parameters. World J. Nano Sci. Eng. 2012, 2, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giacomo, A.; Gaudiuso, R.; Koral, C.; Dell’Aglio, M.; De Pascale, O. Nanoparticle-Enhanced Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy of Metallic Samples. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 10180–10187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Aglio, M.; Alrifai, R.; De Giacomo, A. Nanoparticle Enhanced Laser Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (NELIBS), a First Review. Spectrochim. Acta B At. Spectrosc. 2018, 148, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sherbini, A.M.; Hegazy, H.; El Sherbini, T.M. Measurement of Electron Density Utilizing the Hα-Line from Laser Produced Plasma in Air. Spectrochim. Acta B At. Spectrosc. 2006, 61, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Shi, Y.-J.; Yang, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, Y.-G.; Dang, J.-J.; Yang, S.; Jo, J.; Oh, S.-G.; Chung, K.-J.; et al. Electron Density Profile Measurements from Hydrogen Line Intensity Ratio Method in Versatile Experiment Spherical Torus. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2016, 87, 11E540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousquet, B.; Gardette, V.; Ros, V.M.; Gaudiuso, R.; Dell’Aglio, M.; De Giacomo, A. Plasma Excitation Temperature Obtained with Boltzmann Plot Method: Significance, Precision, Trueness and Accuracy. Spectrochim. Acta B At. Spectrosc. 2023, 204, 106686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thouin, J.; Benmouffok, M.; Freton, P.; Gonzalez, J.-J. Interpretation of Temperature Measurements by the Boltzmann Plot Method on Spatially Integrated Plasma Oxygen Spectral Lines. Eur. Phys. J. Appl. Phys. 2023, 98, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, N.; Usmawanda, T.N.; Lahna, K.; Ramli, M. Temperature Estimation Using Boltzmann Plot Method of Many Calcium Emission Lines in Laser Plasma Produced on River Clamshell Sample. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1120, 012098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrebdi, T.A.; Fayyaz, A.; Asghar, H.; Zaman, A.; Asghar, M.; Alkallas, F.H.; Hussain, A.; Iqbal, J.; Khan, W. Quantification of Aluminum Gallium Arsenide (AlGaAs) Wafer Plasma Using Calibration-Free Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (CF-LIBS). Molecules 2022, 27, 3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sontag-González, M.; Mittelstraß, D.; Kreutzer, S.; Fuchs, M. Wavelength Calibration and Spectral Sensitivity Correction of Luminescence Measurements for Dosimetry Applications: Method Comparison Tested on the IR-RF of K-Feldspar. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.07991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, L.M.; Anoop, K.K. A Numerical Procedure for Understanding the Self-Absorption Effects in Laser Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 29613–29624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramida, A.; Ralchenko, Y. NIST Atomic Spectra Database, NIST Standard Reference Database 78; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MA, USA, 1999.

- Dimitrijević, M.S.; Sahal-Bréchot, S. Stark Broadening of AgI Spectral Lines. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 2003, 85, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrijevic, M.S.; Sahal-Bréchot, S. Stark Broadening Parameter Tables for Neutral Zinc Spectral Lines. Serb. Astron. J. 1999, 160, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djurović, S.; Blagojević, B.; Konjević, N. Experimental and Semiclassical Stark Widths and Shifts for Spectral Lines of Neutral and Ionized Atoms (A Critical Review of Experimental and Semiclassical Data for the Period 2008 Through 2020). J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 2023, 52, 031503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidoro-García, L.; De Andrés-García, I.; Porro, J.; Fernández, F.; Colón, C. Experimental and Theoretical Electron Collision Broadening Parameters for Several Ti II Spectral Lines of Industrial and Astrophysical Interest. Atoms 2024, 12, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sherbini, A.M.; Parigger, C.G. Nano-Material Size Dependent Laser-Plasma Thresholds. Spectrochim. Acta B At. Spectrosc. 2016, 124, 79–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

EL Sherbini, A.; Aboulfotouh, A. Temporal Variation in Nano-Enhanced Laser-Induced Plasma Spectroscopy (NELIPS). Quantum Beam Sci. 2025, 9, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/qubs9040034

EL Sherbini A, Aboulfotouh A. Temporal Variation in Nano-Enhanced Laser-Induced Plasma Spectroscopy (NELIPS). Quantum Beam Science. 2025; 9(4):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/qubs9040034

Chicago/Turabian StyleEL Sherbini, Ashraf, and AbdelNasser Aboulfotouh. 2025. "Temporal Variation in Nano-Enhanced Laser-Induced Plasma Spectroscopy (NELIPS)" Quantum Beam Science 9, no. 4: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/qubs9040034

APA StyleEL Sherbini, A., & Aboulfotouh, A. (2025). Temporal Variation in Nano-Enhanced Laser-Induced Plasma Spectroscopy (NELIPS). Quantum Beam Science, 9(4), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/qubs9040034