Temperature and Fluence Dependence Investigation of the Defect Evolution Characteristics of GaN Single Crystals Under Radiation with Ion Beam-Induced Luminescence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiments and Simulations

3. Experimental Results and Discussion

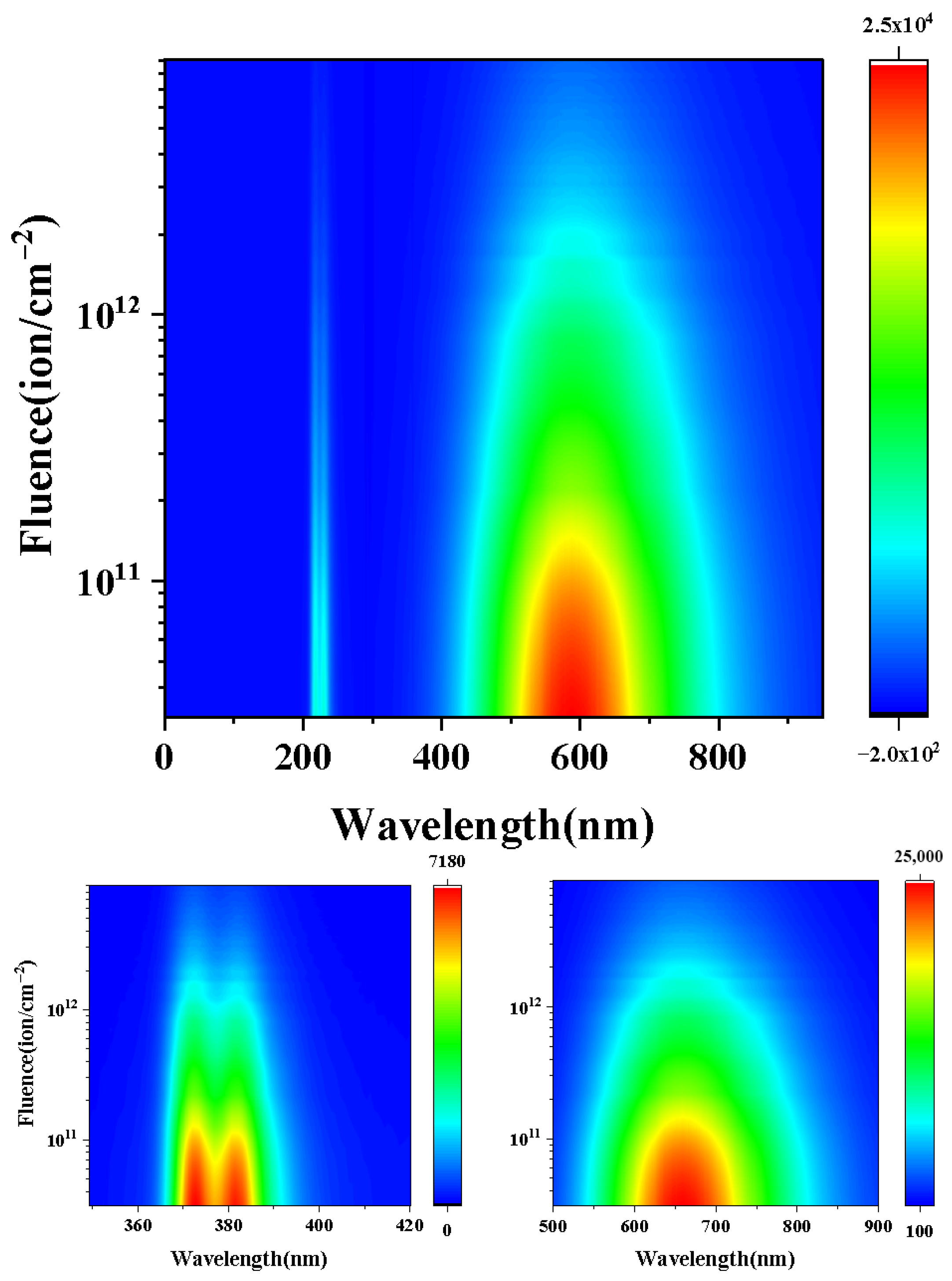

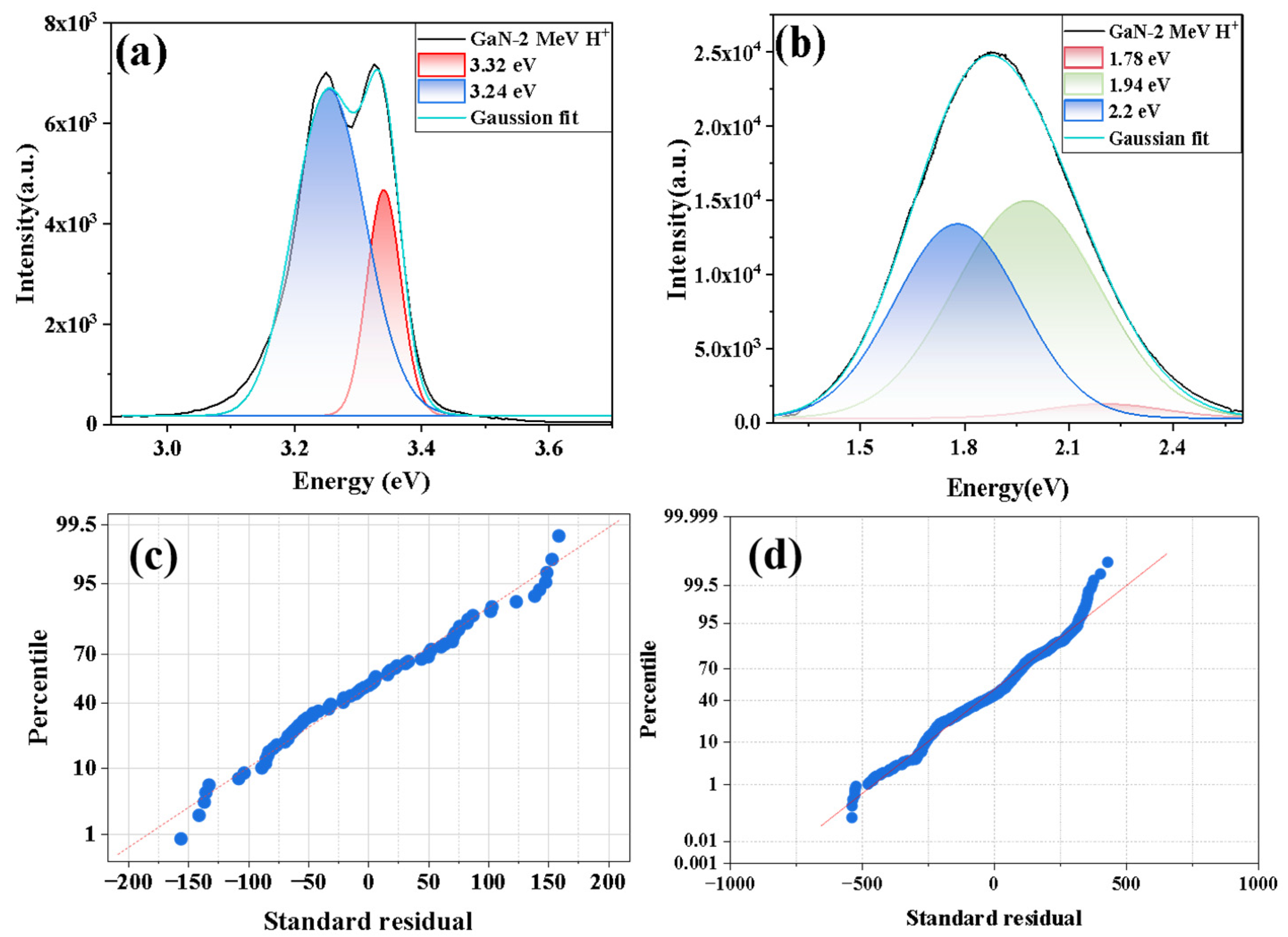

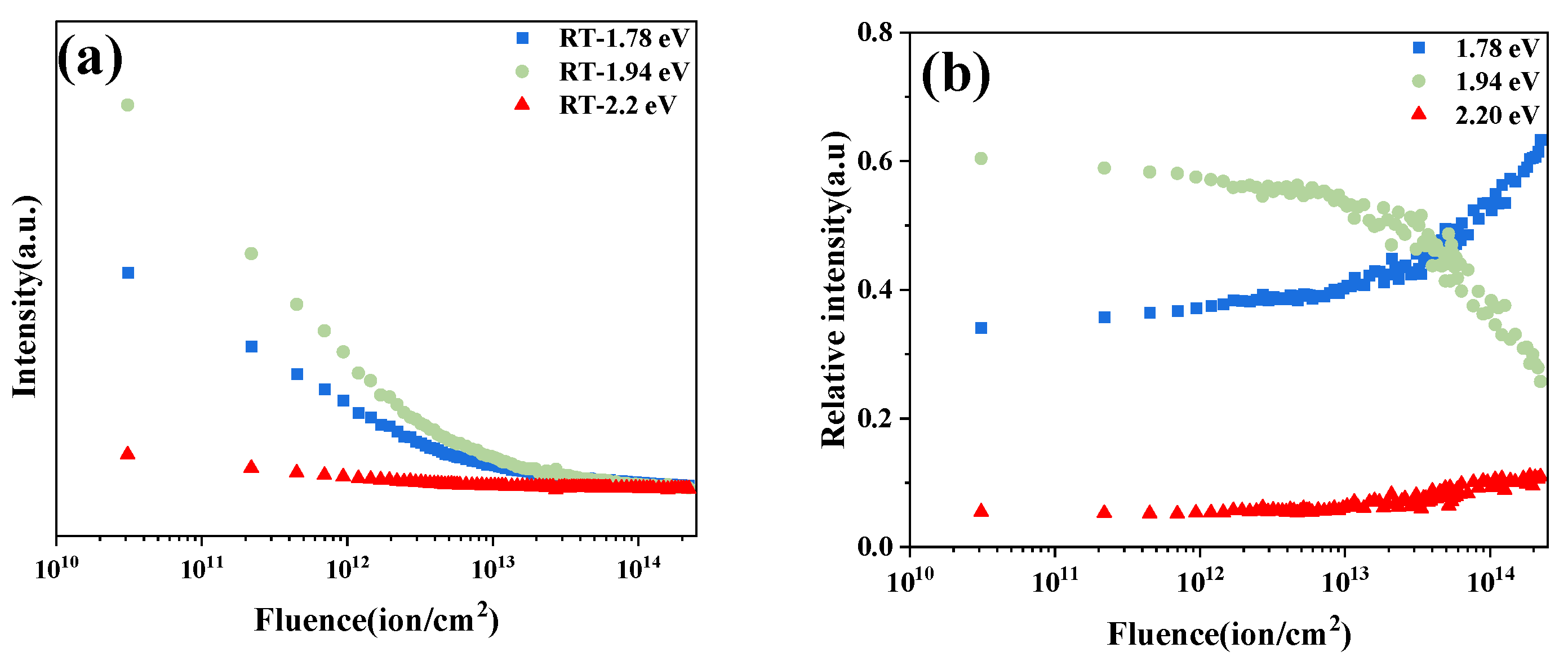

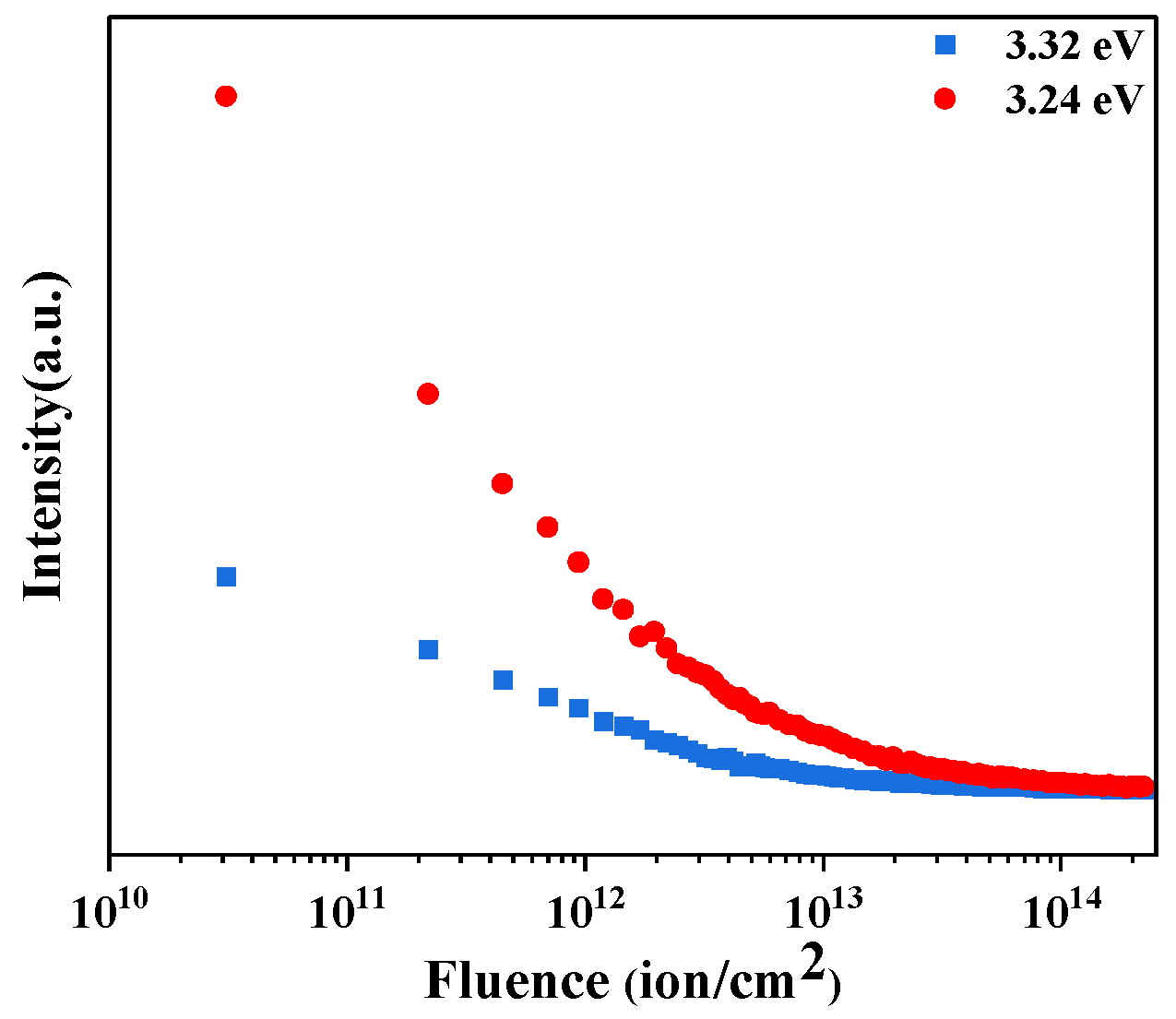

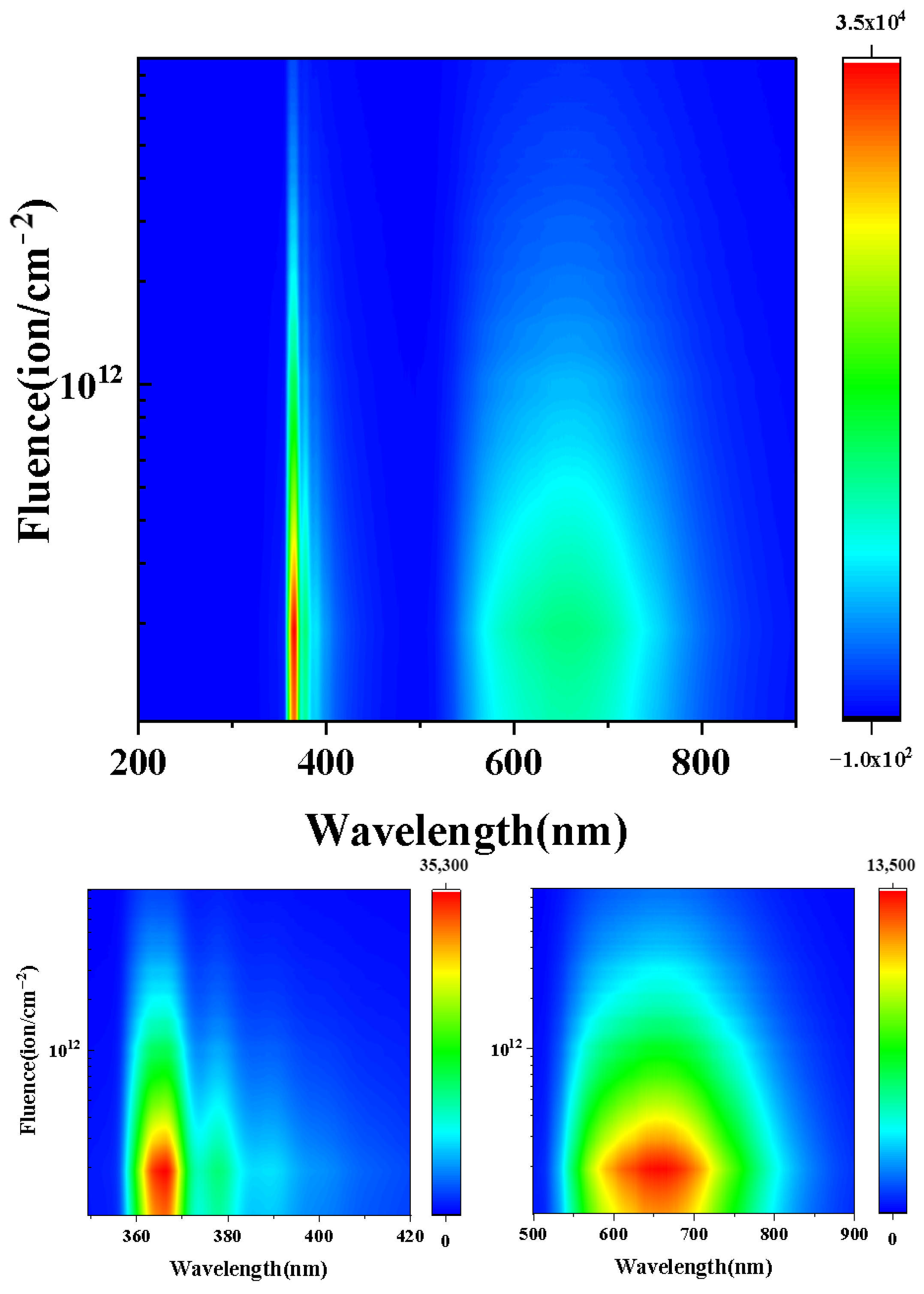

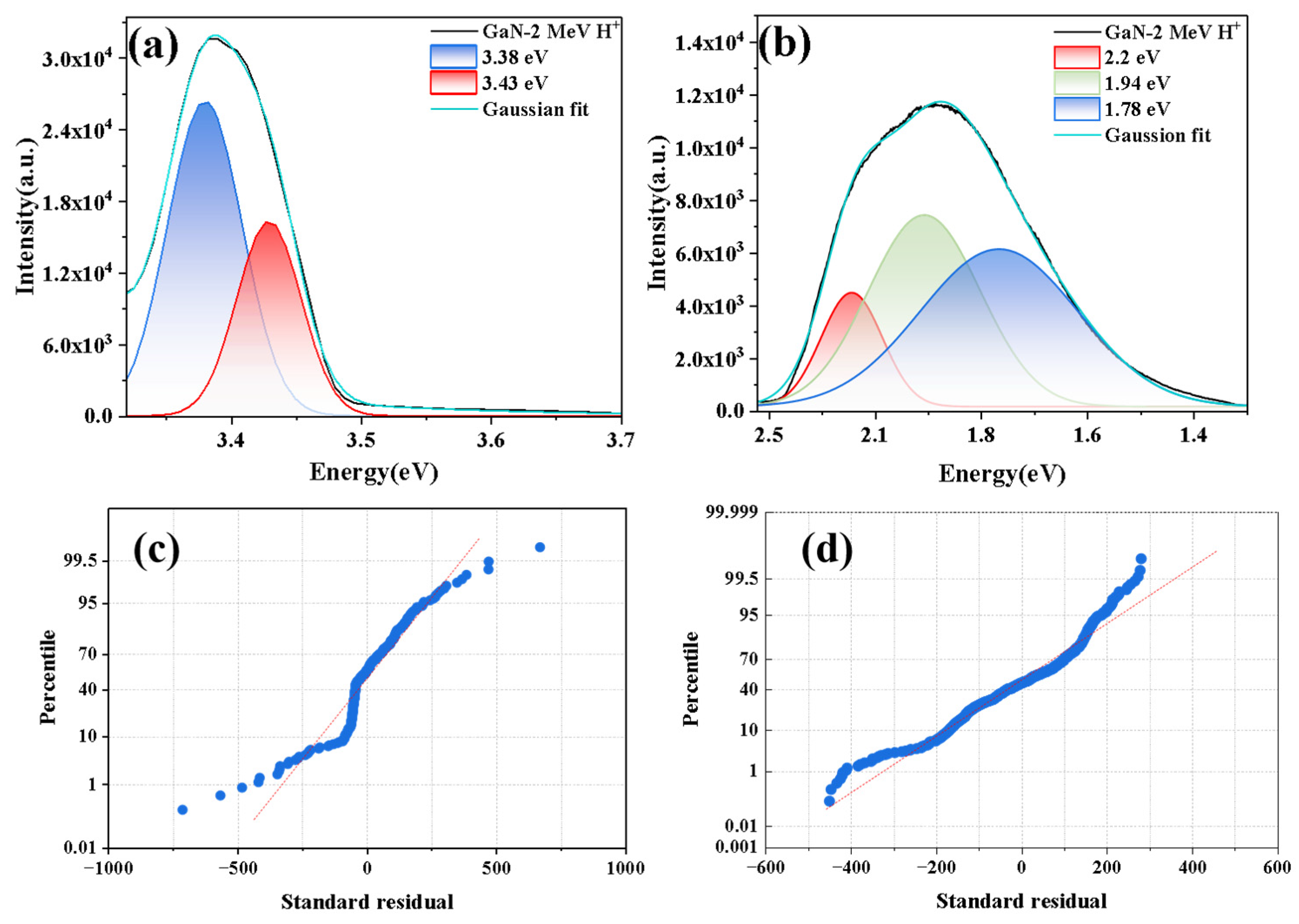

3.1. In Situ IBIL Experiments Under Room-Temperature H+ Irradiation

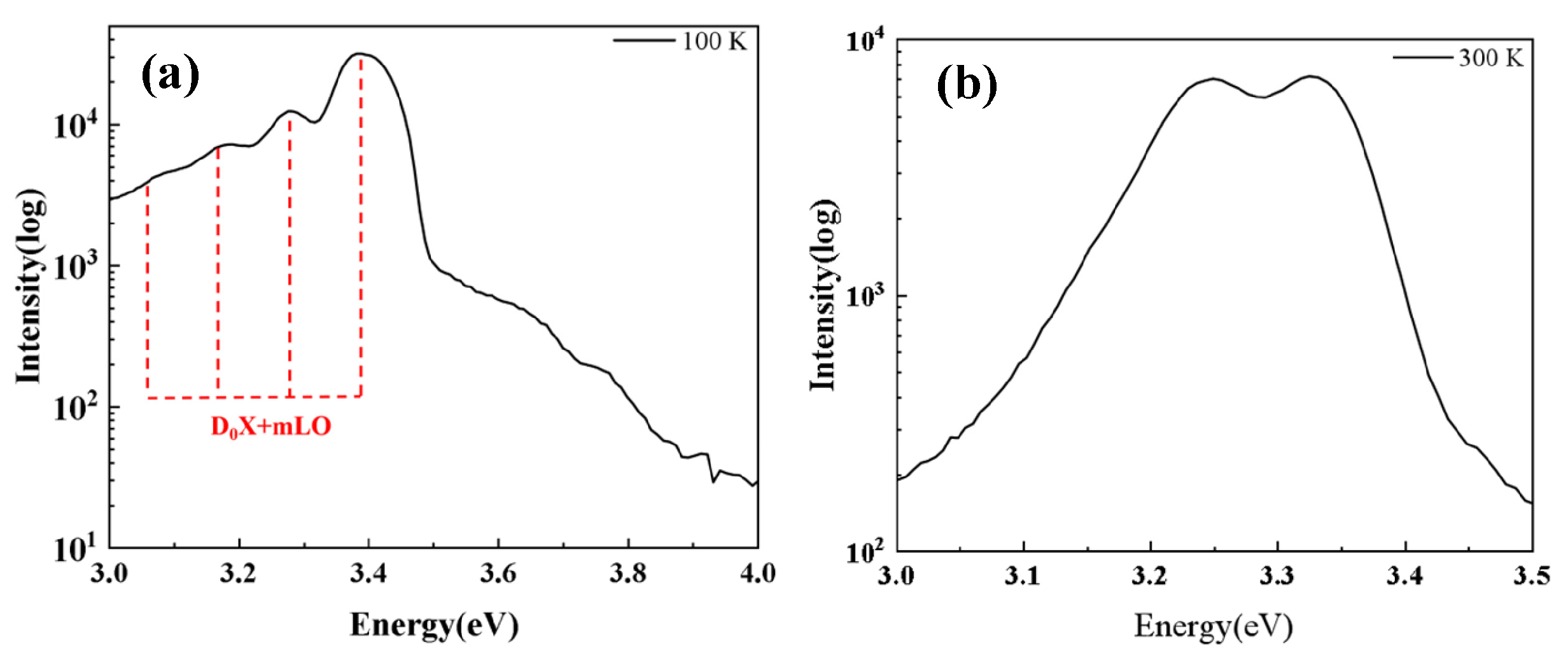

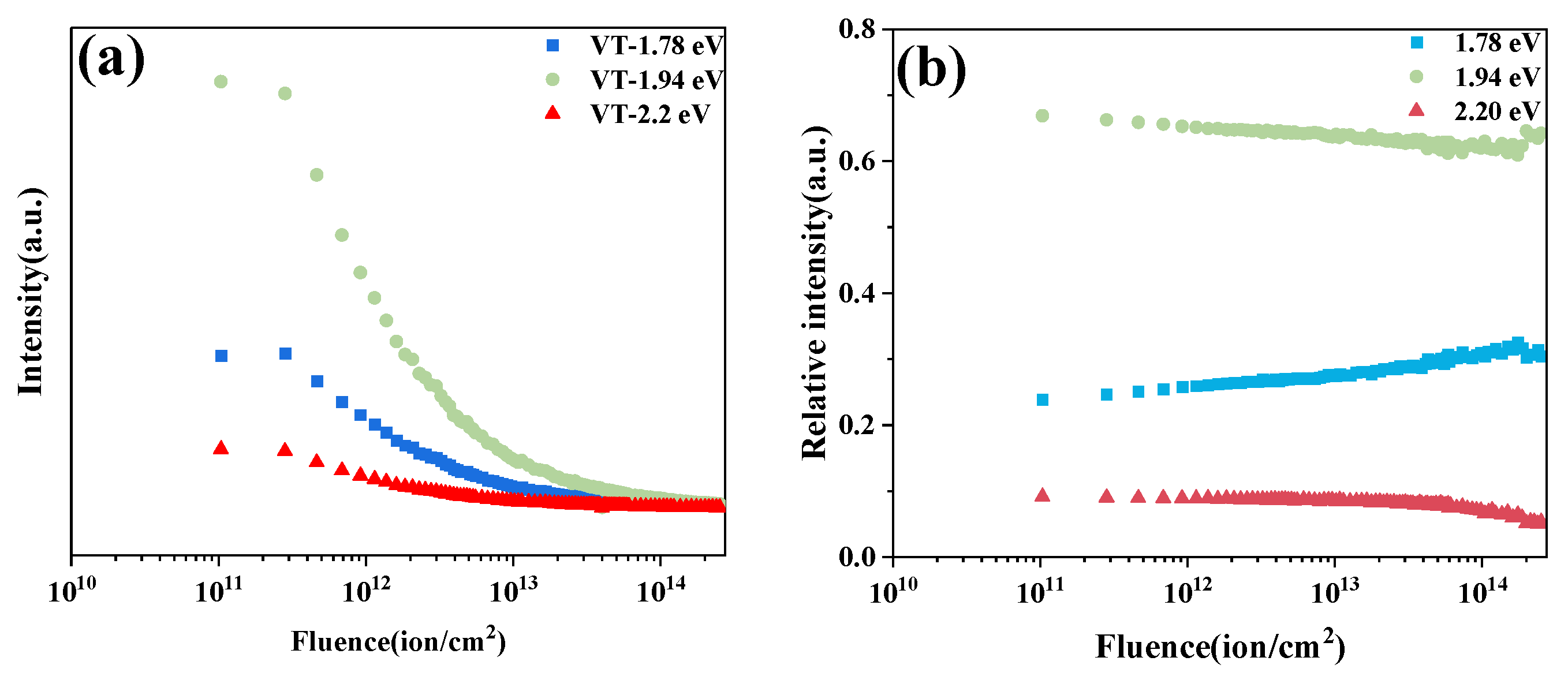

3.2. In Situ Irradiation Luminescence (IBIL) Experiments Under 100–300 K H+ Irradiation

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sharma, R.C.; Nandal, R.; Tanwar, N.; Yadav, R.; Bhardwaj, J.; Verma, A. Gallium arsenide and gallium nitride semiconductors for power and optoelectronics devices applications. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2426, 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musumeci, S.; Vincenzo, B. Gallium nitride power devices in power electronics applications: State of art and perspectives. Energies 2023, 16, 3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Raman, A.; Ranjan, R. GaN-Based High Electron Mobility Transistor. In Semiconductor Nanoscale Devices: Materials and Design Challenges; Bentham Science Publishers: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2025; pp. 193–212. [Google Scholar]

- Polyakov, A.Y.; Pearton, S.J.; Frenzer, P.; Ren, F.; Liu, L.; Kim, J. Radiation effects in GaN materials and devices. J. Mater. Chem. C 2013, 1, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, M.C.; Mattei, J.G.; Vazquez, H.; Djurabekova, F.; Nordlund, K.; Monnet, I.; Mota-Santiago, P.; Kluth, P.; Grygiel, C.; Zhang, S.; et al. Unravelling the secrets of the resistance of GaN to strongly ionising radiation. Commun. Phys. 2021, 4, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Mulligan, P.; Brillson, L.; Cao, L.R. Review of using gallium nitride for ionizing radiation detection. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2015, 2, 031102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Q.; Yang, M.; Cheng, Q.; Liu, J.; Liu, S. Study on proton irradiation effect of GaN optical and electrical properties. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2023, 83, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankove, J.; Hutchby, J. Photoluminescence of ion-implanted GaN. J. Appl. Phys. 1976, 47, 5387–5390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, E.R.; Kennedy, T.A.; Doverspike, K.; Rowland, L.B.; Gaskill, D.K.; Freitas, J.A., Jr.; Asif Khan, M.; Olson, D.T.; Kuznia, J.N.; Wickenden, D.K. Optically detected magnetic resonance of GaN films grown by organometallic chemical-vapor deposition. Phys. Rev. B 1995, 51, 13326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, L.T.; Lin, K.; Chang, E.; Huang, W.C.; Hsiao, Y.L.; Chiang, C.H. Photoluminescence and Raman studies of GaN films grown by MOCVD. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2009, 187, 012021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, G.; Wessels, B. Compensation of n-type GaN. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1996, 69, 3028–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Kung, P.; Saxler, A.; Walker, D.; Wang, Τ.; Razeghi, M. Photoluminescence Study of GaN. Acta Phys. Pol. A 1995, 88, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, D.; Kovalev, D.; Steude, G.; Meyer, B.K.; Hoffmann, A.; Eckey, L.; Heitz, R.; Detchprom, T.; Amano, H.; Akasaki, I. Properties of the Yellow luminescence in undoped GaN epitaxial layers. Phys. Rev. B 1995, 52, 16702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.M.; Chen, Y.G.; Lee, M.C.; Feng, M.S. Yellow luminescence in n-type GaN epitaxial films. Phys. Rev. B 1997, 56, 6942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshchikov, M.A.; Hadis, M. Luminescence properties of defects in GaN. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 97, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshchikov, M.A. On the Origin of the Yellow Luminescence Band in GaN. Phys. Status Solidi (b) 2023, 260, 2200488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, J.L.; Janotti, A.; de Walle, C.G.V. Carbon impurities and the yellow luminescence in GaN. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 97, 152108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Ran, G.; Zhang, J.; Duan, X.F.; Lian, W.C.; Qin, G.G. C and Si ion implantation and the origins of yellow luminescence in GaN. Appl. Phys. A 2004, 79, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshchikov, M.A.; Korotkov, R.Y. Analysis of the temperature and excitation intensity dependencies of photoluminescence in undoped GaN films. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 64, 115205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, J.F.; Ziegler, M.D.; Biersack, J.P. SRIM—The stopping and range of ions in matter (2010). Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B-Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2010, 268, 1818–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Song, C.; Liao, H.; Yang, N.; Wang, R.; Tang, G.; Cao, W. Theoretical investigation of electronic structure and thermoelectric properties of CN point defects in GaN. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 969, 172398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, R.; Hong, W.; Yang, Q.; Feick, H.; Gebauer, J.; Weber, E.R.; Hautakangas, S.; Saarinen, K. Contributions from gallium vacancies and carbon-related defects to the “yellow luminescence” in GaN. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2003, 82, 3457–3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Richter, E.; Weyers, M. Red luminescence from freestanding GaN grown on LiAlO2 substrate by hydride vapor phase epitaxy. Phys. Status Solidi (a) 2007, 204, 846–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshchikov, M.A.; Usikov, A.; Helava, H.; Makarov, Y. Fine structure of the red luminescence band in undoped GaN. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 032103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Rey, D.; Peña-Rodríguez, O.; Manzano-Santamaría, J.; Olivares, J.; Muñoz-Martín, A.; Rivera, A.; Agulló-López, F. Ionoluminescence induced by swift heavy ions in silica and quartz: A comparative analysis. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2012, 286, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshchikov, M.A. Photoluminescence from defects in GaN. Gallium Nitride Materials and Devices XVIII. SPIE 2023, 12421, 58–72. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, M.L.; Yin, P.; Wang, G.F.; Song, J.G.; Luo, C.W.; Wang, T.S.; Zhao, G.Q.; Lv, S.S.; Zhang, F.S.; Liao, B. In situ luminescence measurement of 6H-SiC at low temperature. Chin. Phys. B 2020, 29, 046106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Wang, G.F.; Qiu, M.L.; Chu, Y.J.; Xu, M.; Yin, P. Ionoluminescence spectra of a ZnO single crystal irradiated with 2.5 MeV H+ ions. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2017, 34, 087801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedhain, A.; Li, J.; Lin, J.Y.; Jiang, H.X. Nature of deep center emissions in GaN. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 96, 151902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, T.; Jiang, H.; Xu, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, P.; Gao, P.; et al. Phonon dispersion of buckled two-dimensional GaN. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunea, G.E.; Herzog, W.D.; Ünlü, M.S.; Goldberg, B.B.; Molnar, R.J. Time-resolved photoluminescence studies of free and donor-bound exciton in GaN grown by hydride vapor phase epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1999, 75, 838–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| q | /eV |

|---|---|

| 0 | 6.76 |

| 1 | 4.25 |

| −1 | 13.49 |

| −2 | 9.53 |

| −3 | 11.09 |

| Sample | 3.32 eV | 3.24 eV | 1.78 eV | 1.94 eV | 2.2 eV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single crystal GaN | 1.27 × 1012 ± 1.19 × 1011 | 1.20 × 1012 ± 1.11 × 1011 | 1.60 × 1012 ± 1.26 × 1011 | 1.24 × 1012 ± 1.08 × 1011 | 1.35 × 1012 ± 1.22 × 1011 |

| R2 | 0.96040 | 0.97655 | 0.95552 | 0.95307 | 0.95384 |

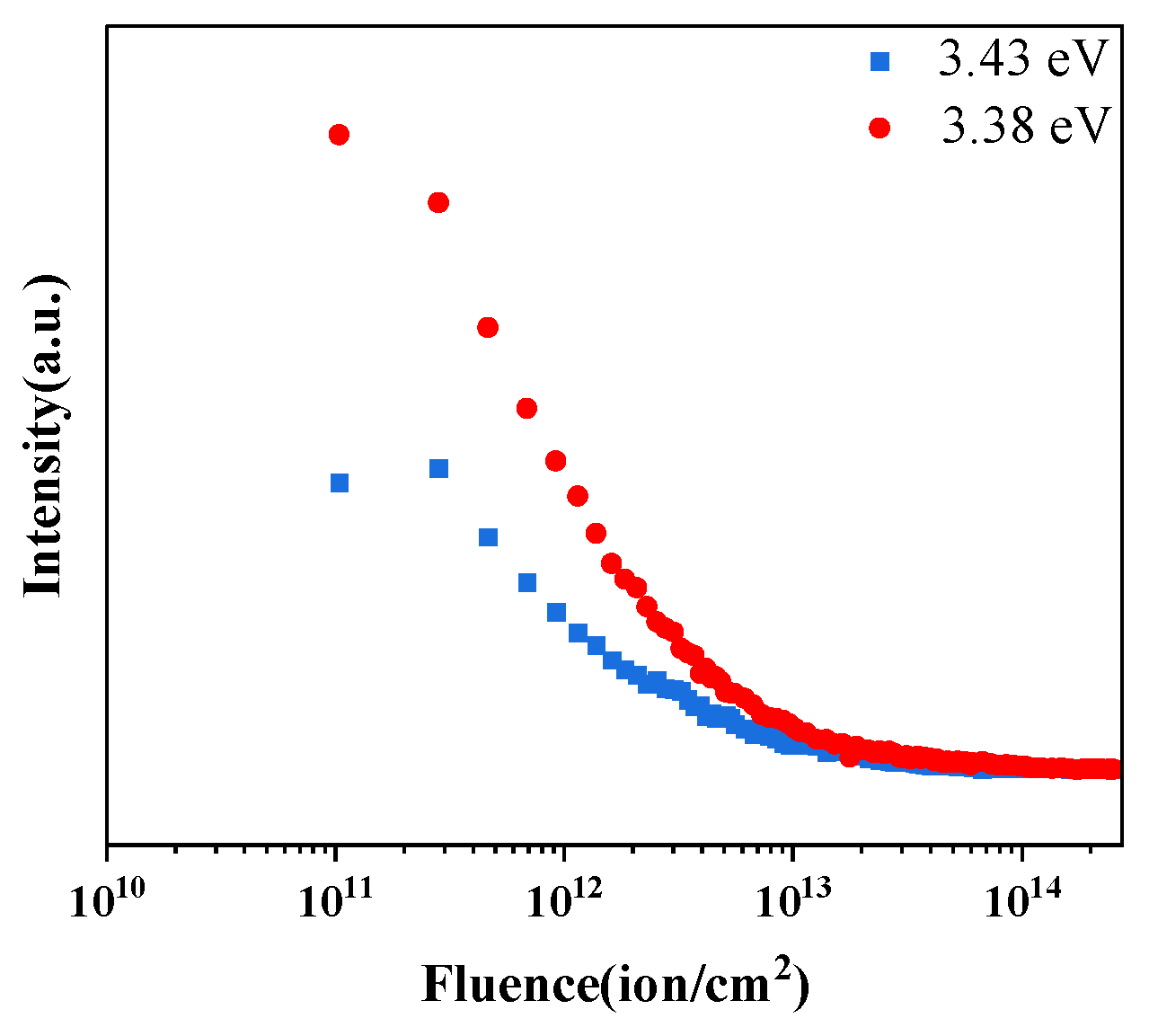

| Temperature Conditions | 3.43 eV | 3.38 eV | 1.78 eV | 1.94 eV | 2.2 eV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single crystal GaN | 1.27 × 1012 ± 1.19 × 1011 | 1.20 × 1012 ± 1.11 × 1011 | 1.60 × 1012 ± 1.26 × 1011 | 1.24 × 1012 ± 1.08 × 1011 | 1.35 × 1012 ± 1.22 × 1011 |

| Variable temperature (100–300 K)-f | 1.54 × 1012 ± 1.03 × 1011 | 1.51 × 1012 ± 7.23 × 1010 | 1.88 × 1012 ± 2.16 × 1011 | 6.19 × 1012 ± 3.65 × 1011 | 1.63 × 1012 ± 2.02 × 1011 |

| R2 | 0.95162 | 0.96389 | 0.96329 | 0.96381 | 0.9629 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Peng, X.; Jiang, W.; Chang, R.; Hu, H.; Lv, S.; Ouyang, X.; Qiu, M. Temperature and Fluence Dependence Investigation of the Defect Evolution Characteristics of GaN Single Crystals Under Radiation with Ion Beam-Induced Luminescence. Quantum Beam Sci. 2026, 10, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/qubs10010002

Peng X, Jiang W, Chang R, Hu H, Lv S, Ouyang X, Qiu M. Temperature and Fluence Dependence Investigation of the Defect Evolution Characteristics of GaN Single Crystals Under Radiation with Ion Beam-Induced Luminescence. Quantum Beam Science. 2026; 10(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/qubs10010002

Chicago/Turabian StylePeng, Xue, Wenli Jiang, Ruotong Chang, Hongtao Hu, Shasha Lv, Xiao Ouyang, and Menglin Qiu. 2026. "Temperature and Fluence Dependence Investigation of the Defect Evolution Characteristics of GaN Single Crystals Under Radiation with Ion Beam-Induced Luminescence" Quantum Beam Science 10, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/qubs10010002

APA StylePeng, X., Jiang, W., Chang, R., Hu, H., Lv, S., Ouyang, X., & Qiu, M. (2026). Temperature and Fluence Dependence Investigation of the Defect Evolution Characteristics of GaN Single Crystals Under Radiation with Ion Beam-Induced Luminescence. Quantum Beam Science, 10(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/qubs10010002