4.1. AHP and Fuzzy AHP

The AHP questionnaires were distributed to government agencies and state enterprises owning the infrastructures and regulating air and rail transport, airport operators, railway operators, and airlines. The target respondents are the mid-level managers to executive personnel (or other positions equivalent to the indicated managerial positions). The minimum requirement of work experience for the respondent was 10 years. Information other than the respondent’s affiliation, job level, and work experience were not recorded. Hence, personal data, backgrounds, demographics, and psychological information of respondents were not collected.

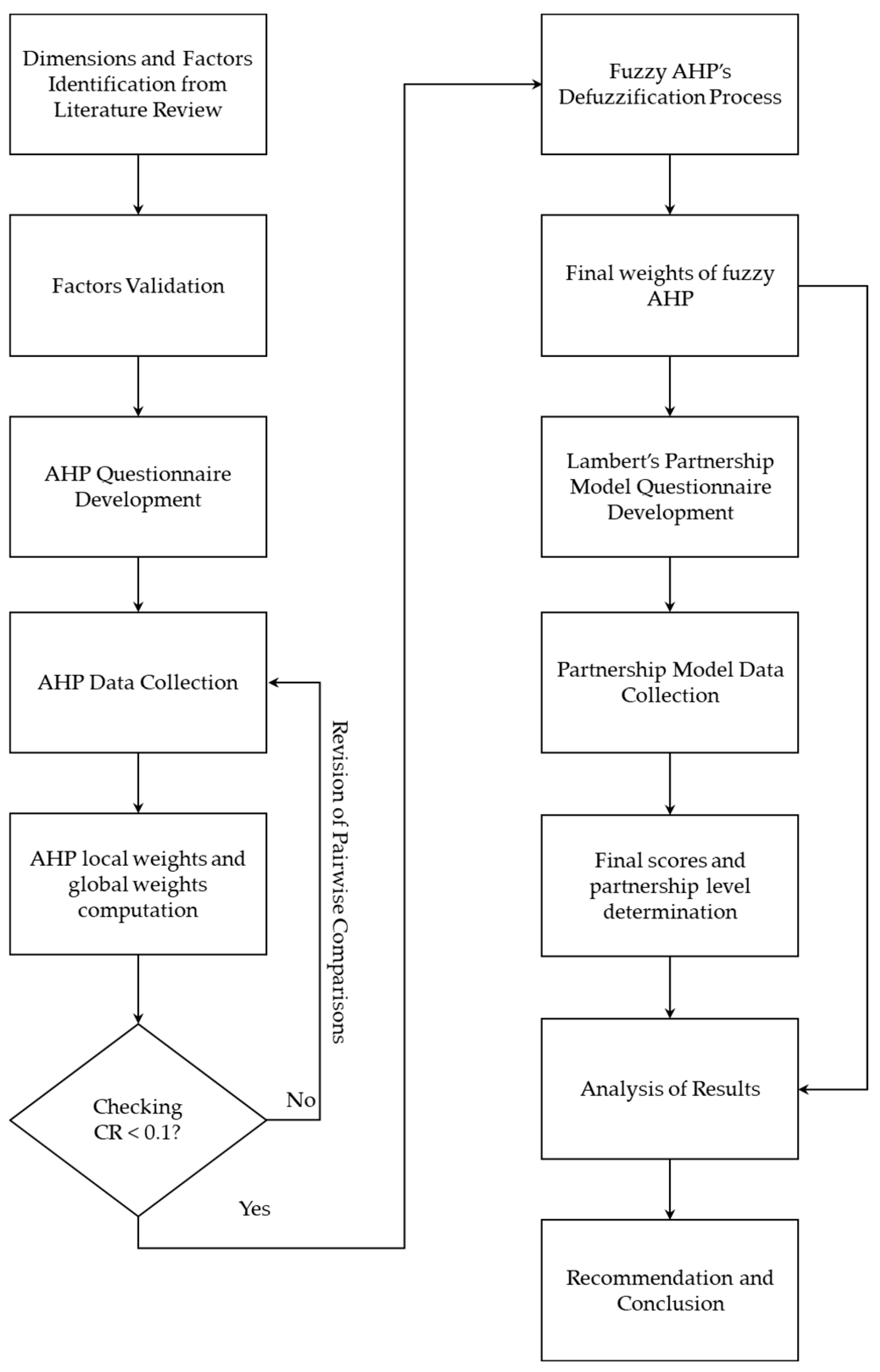

The data collection (including the revision and request for further comment period) was held during March and November 2023. Out of 30 questionnaires, 24 were retrieved. Three responses were excluded from the final analysis due to significant inconsistencies and the revision of pairwise comparisons could not be made. Therefore, the total number of usable responses was 21—12 being regulators and 9 being operators. As discussed by [

38], AHP does not require a large sample size as it aims to provide an analysis of decision-making results regardless of the identity or behavior of the decision makers. In addition, a study by [

39] suggested the standard observations to be between 19 and 400, with a margin of error at five percent. Hence, the number of respondents of 21 in this work would be considered sufficient. The average consistency ratios of the two groups are shown in

Table 7. The average work experience of 21 respondents is 16.9 years.

The administration and economics dimensions contain two factors, resulting in one pairwise comparison and automatically a 0.0000 value of CR. As the overall average CR values in all dimensions, factors under infrastructure, and factors under social do not exceed 0.1000, the quantitative outputs of the questionnaire were usable for further analysis.

Table 8 presents the local weights from the AHP and fuzzy AHP approaches, classified by two groups of respondents: regulators and operators.

The global weights are computed by multiplying the local weight of a factor with the local weight of its respective dimension. Therefore, the calculation of a dimension’s global weight is not applicable. It can be seen that both regulators and operators considered infrastructure and economics to be one of the most important dimensions that lead to air–rail integration success. At factor levels, price, times, and safety and security were among the most important factors affecting the success of air–rail integration.

Evidently, the defuzzification process has signified the weights of the highly prioritized dimensions, resulting in greater local weights in the fuzzy AHP approach for the infrastructure, economic, and administration dimensions, while the social dimension’s weight has been diminished. Similarly, local weights of some factors such as safety and security (A1) and accessibility (I1) were extensively amplified under fuzzy AHP while the local weights of time (E2) and seamless journey (I3) shrunk. Consequently, global weights of both approaches were dissimilar.

Figure 6 illustrates the fuzzy AHP global weights classified by the groups of respondents.

The group visualization shows that regulators and operators viewed the relative importance of each factor differently. While operators’ main priorities were price (E1), safety and security (A1), seamless journey (I3), and time (E2), the regulators placed their attention on safety and security (A1), accessibility (I1), price (E1), and coverage (I2). However, both groups agreed that the social factors including career opportunities (S1), social welfare (S2), and cultural and lifestyle (S3) were of the least concern. Selected factors under the economic and infrastructure dimensions will be further discussed.

Price (E1) was ranked as the overall top priority factor that would lead to air–rail integration success. While this factor appears to be the most significant factor for the operators, the regulators had a different perspective. As price was not defined as a transportation fare but the compromised value that passenger is willing to accept in exchange for transportation service, the operators commented that the price should be more approachable for potential users and train riders which in return require a large number of subsidies so that the fares in the air–rail integration project are attractive enough to generate the desirable and sustainable growth rate of transportation demand. However, regulators viewed price as a responsibility of operators as the project would be commenced under a certain form of a public–private partnership, in which subsidies may not take place at all.

While operators focused largely on seamless journeys (I3), it was not considered as one of the top priorities by the regulators. According to the respondents’ further comments, the lack of fundamental seamless journey features, infrastructure accessibility, and willingness to participate by air carriers are attributed to the failure of air–rail integration in the past projects. This would potentially impact the success of the future air–rail integration project as the planning and implementation of a seamless journey’s features are necessary elements in the connectivity of air–rail trips.

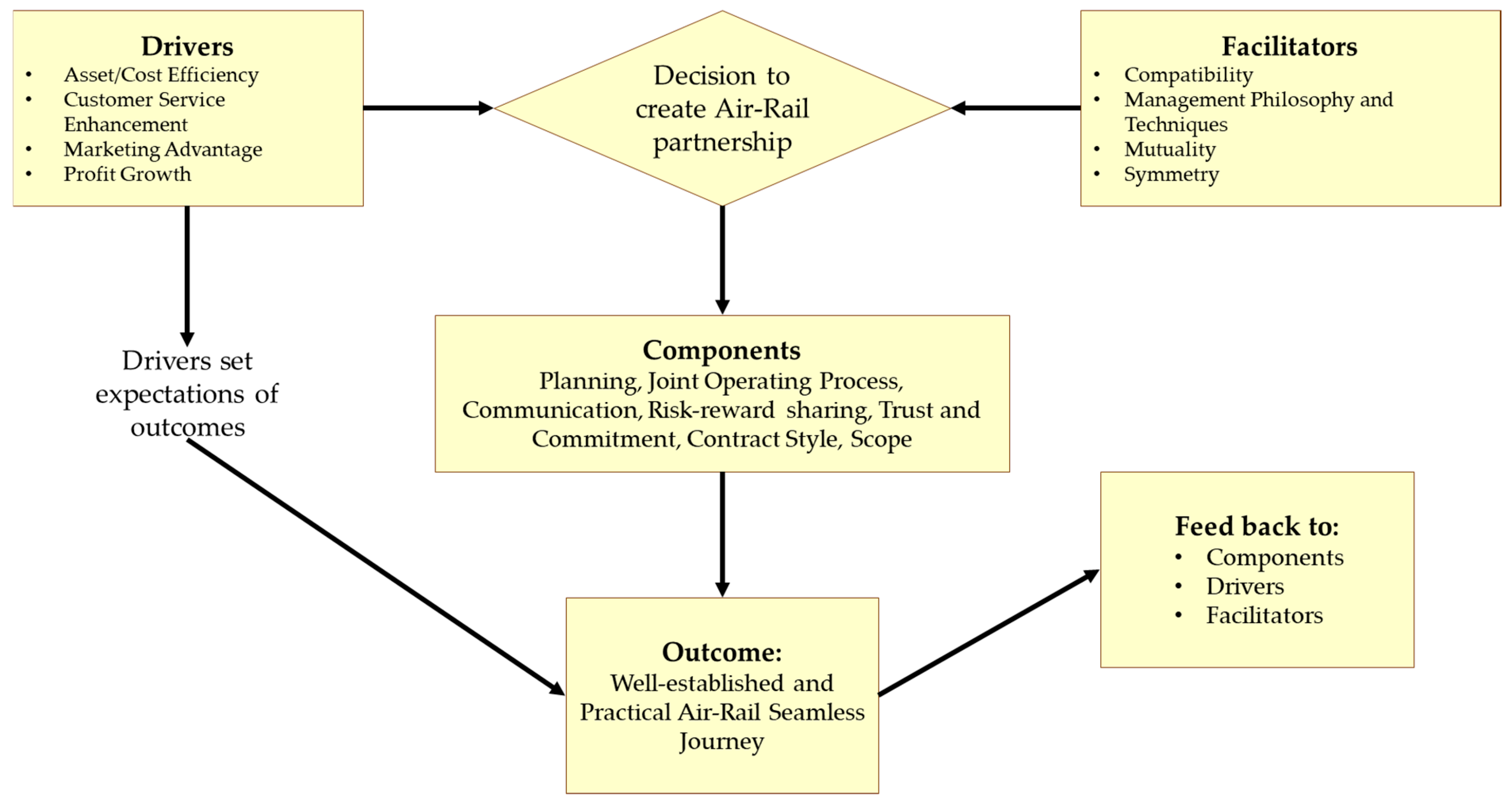

4.2. Application with the Partnership Model: Perspectives of the Operators

The target respondents of partnership assessment are mid-level managers to executive personnel of airport operators, train operators, and air carriers that operate domestically and internationally in Thailand. The authors focused only the operators’ cases because, based on the AHP data collection, the transportation regulators are willing to encourage the seamless journey and air–rail integration to succeed, while the operators expressed doubt as to whether the integration would be a flourishing one. By using the partnership assessment model, it would potentially suggest the decision to partner to the stakeholders and the level of partnership required for the success of air–rail integration. There were five returned responses out of nine distributed questionnaires. Respondents’ personal data, backgrounds, demographics, and psychological information were not collected. The average scores in each perspective are shown in

Table 9.

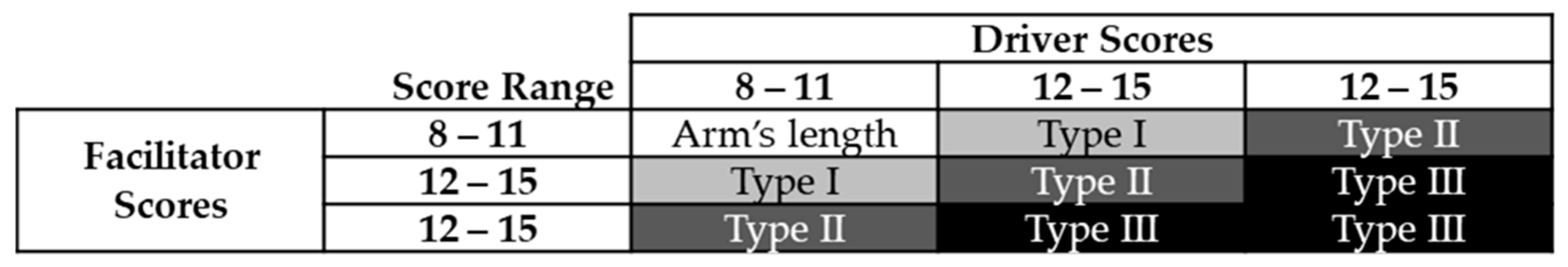

The average score for all drivers and the first four facilitator perspectives are based on a full mark of 5.0, with the exclusion of the extra points from the sustainable competitive advantage evaluation in the driver section. It can be noted that all respondents had a consensus on two aspects: the key stakeholders are in close physical proximity to each other and the stakeholders share high-value end users. The partnership level can be identified by using the propensity to partner matrix from

Figure 4 by using the total scores—14.6 from drivers and 16.6 from facilitators. The final classifications resulted in the Type III partnership.

Although two out of five responses revealed the desired partnership level to be Type II, by using average driver and facilitator scores, the required partnership level for air–rail integration success is Type III, indicating the demand for extremely close collaboration in all aspects between train operators, airport operators, and air carriers with strong support from government agencies. However, based on the collected data, it can be noted that most respondents do not believe that the asset and cost efficiency, customer service, marketing advantage, and growth and stability in profit would bring a sustainable competitive advantage to stakeholders despite favoring each driver at more than 50% likelihood. This suggests the lack of confidence from the operators’ perspectives that the partnership and collaboration between stakeholders would be sustainable while competitive advantages, if they exist, may not last.

The Type III partnership directs that the air–rail integration should include a high level of partnership components, including the systematic joint planning among stakeholders on a continuous basis and at multiple levels from operational to executive. Joint operating controls and the scope of activities ranging from coordinated flights and train schedules; one-stop online reservation; single itinerary (or integrated ticket); code-sharing; baggage check-in, drop-off, and transfer service at major train stations; delay and/or cancellation assistance; to extended end-to-end service are mandatory. Effective communication across the stakeholders’ organization is also essential at all levels while integrated electronic communication platforms used by all parties are recommended. As one of the cores of partnership is sharing both risk and rewards, the integrated frequent flyer and rider program (or mileage collection program) and special discount can be implemented as one of the air–rail partnership offerings. The contract style and form of financial investment are some of the key components for the success air–rail integration, as the DMK-BKK-UTP HSR project which is worth approximately USD 6270.44 billion was set to commence under the PPP agreement. The PPP contractual style refers to the net cost which the concessionaire (railways operator) must invest into the infrastructure works and operational works while the government would provide subsidies only when the fares and ancillary revenues are less than the cost incurred by the concessionaire. By further investigating the PPP form, it can be observed that the net cost style does not support the risk-sharing component as the concessionaire assumes all ridership risks while having to share extra profit with the government [

5]. This means that the airport operators and the airlines do not take part in the financial investment. However, both parties can still provide technological and people investment through joint product and service research and development regularly and the shared personnel in each party’s executive board of directors. Above all, regulators and policy makers must play crucial roles in driving the joint operating controls and risk/reward sharing to succeed by the provision of necessary support and stimulation which may include subsidiaries during the early years of operations when the mobility and the usage of air–rail infrastructure are insufficient. The lack of a high level of regulators’ and policy makers’ support would prominently lead to the repeated history of failed collaboration.