Data-Driven Prediction of Cement-Stabilized Soils Tensile Properties

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Soils

- Soil A

- Soil B

| Properties | Reference | Soil A | Soil B |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density of soil particles, ρs | [38] | 2.59 g/cm3 | 2.64 g/cm3 |

| Liquid limit, WL | [39] | 30% | 38% |

| Plastic limit, WP | 17% | 25% | |

| Plasticity index, (PI = WL − WP) | 13% | 13% | |

| Clay content (d < 2 μm) a, C2μm | [37] | 24% | 6% |

| Silt (2 μm < d < 63 μm) a | 69% | 11% | |

| Sand (63 μm < d < 2 mm) a | 6% | 40% | |

| Gravel (2 mm < d < 200 mm) a | 1% | 43% | |

| AASHTO b classification | [40] | A-6(11) | A-2-6(0) |

| GTR c classification d | [41] | B5 | A2 |

| USCS d classification c | [42] | CL | SM-SC |

2.1.2. CSS—Treatment and Sample Preparation

- OMC = 15.5%, MDD = 1.79 g/cm3 for mixture A

- OMC = 10.0%, MDD = 1.98 g/cm3 for mixture B

2.2. Indirect Tensile Strength

2.3. Statistical Approach

2.3.1. Analysis of Variance

- is the experimental measurement of ITS when the factors CT, CC, DC and W are in the th, -th, -th and -th level, respectively, for the -th replicate;

- is the overall mean effect, is the effect of the -th level of the CT factor, is the effect of the -th level of the CC factor, is the effect of the -th level of the DC factor and is the effect of the -th level of the W factor;

- is the error (or residual) component. It is assumed normally distributed with a constant variance SD2ε and zero mean ().

2.3.2. Regression Model

2.4. Numerical Approach

2.4.1. Experimental Design

2.4.2. Numerical ITS Values and Prediction Models

2.4.3. Model Similarity

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Experimental Results

3.2. Statistical Approach

3.2.1. Analysis of Individual Responses

3.2.2. ANOVA

3.2.3. Multilinear Regression

3.2.4. Coded Multilinear Regression

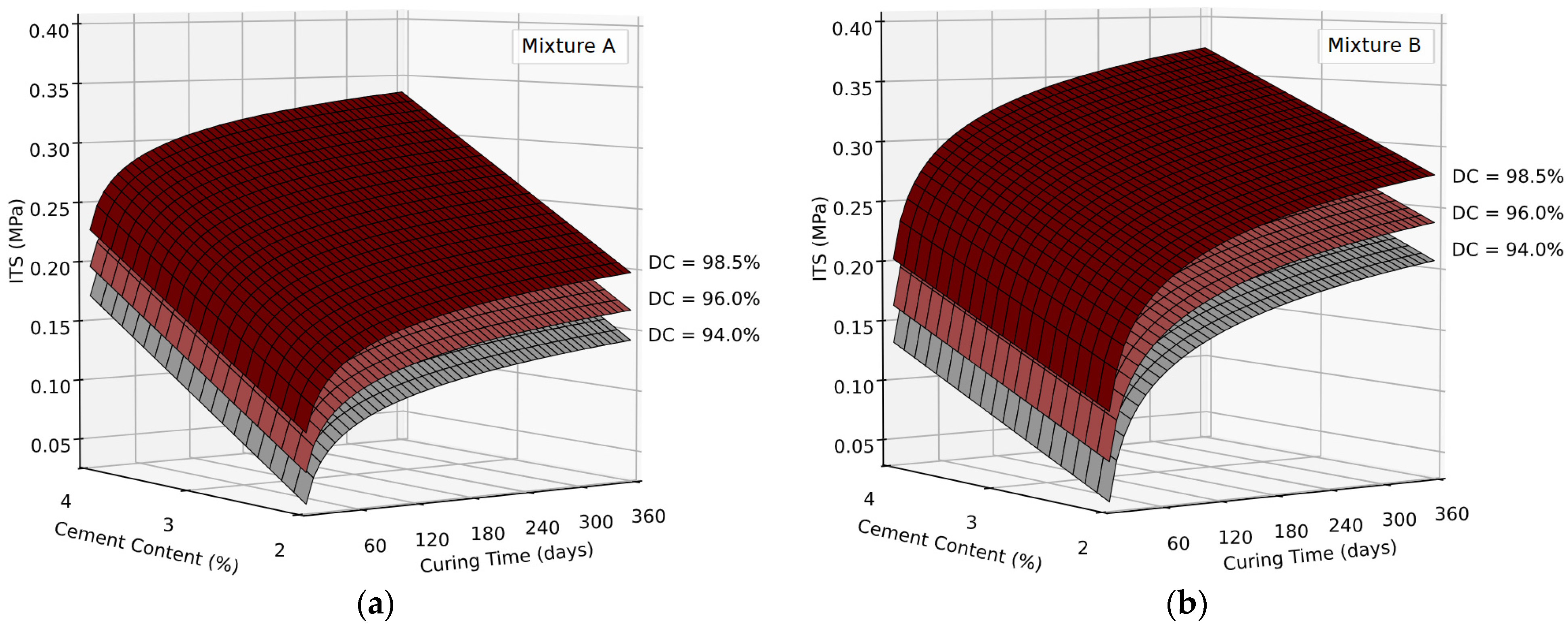

3.2.5. Response Surfaces

3.3. Numerical Approach

4. Conclusions

- The addition of a few percentage points of cement significantly increased the overall performance of both sandy and clayey soils. Mean treated ITS values for the reference mixture varied from 7 up to 11 times the non-treated ITS for mixture A, and from 12 up to 31 times for mixture B.

- The content of water variations in the interval we studied (±10% OMC) showed no significant effects on ITS values for both mixtures. Once this variable was excluded, density was identified as the factor with the lowest effect. Conversely, CC and CT proved to be most significant variable on mixture A and B, respectively.

- The experimental ITS was described accurately by using dosage variables and curing time as predictors on multilinear regression models: R2 of 0.84 and 0.92 for mixture A and B, respectively. The effects of CC were stronger on the clayey soil (A) whereas the influence of CT and DC showed to be higher on the sandy mixture (B).

- The ANOVA proved to be a straightforward method to construct experimental prediction models. These models can be used to interpolate conditions that were not explicitly evaluated in the experimental program. Preparation parameters are ranked regarding their effect on ITS values.

- The combined effects of dosage variables were assessed by means of contour plots. These tools can be used for mixture optimization according to technical specifications and operating conditions.

- The combined effects of dosage variables were observed on the response of surfaces and associated contour plots. These tools can be used to assess specifications for mixture optimization, and operating conditions from short to long-term.

- Long-term results can be achieved in several days by increasing CC. Reducing the binder consumption can be achieved by increasing CT or DC. Specifically, the effects of compaction were shown to be relevant even in the long-term in both materials.

- The residual values of experimental models are well described with normal PDFs. These statistical descriptions were used to generate numerical data.

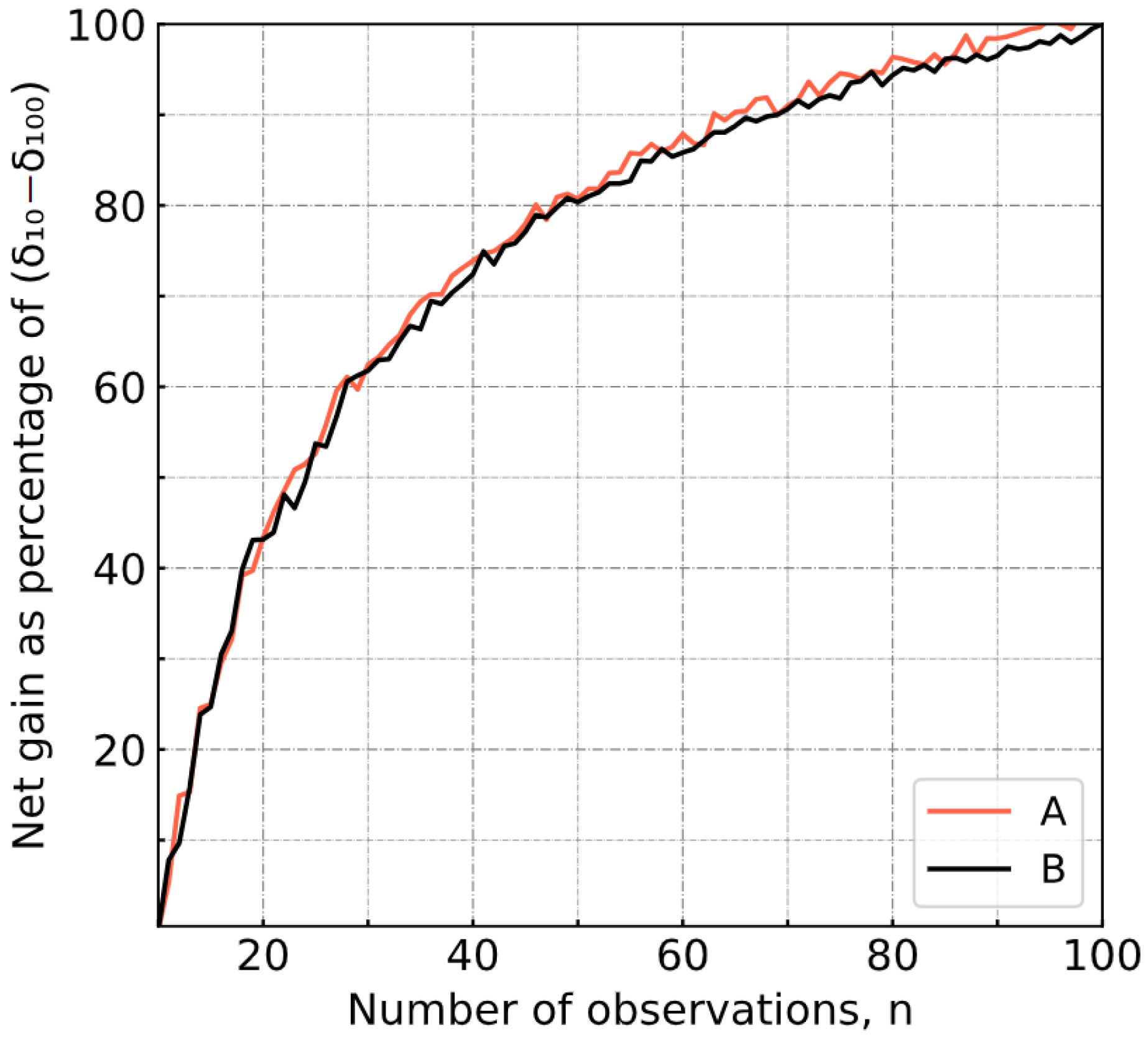

- LHS as space-filling technique was a powerful method to generate efficiently numerical sampling data.

- As expected, the number of observations was critical in explaining the differences between experimental and numerical models. The results showed that regardless of material type, the complete sampling size (n~100) may not be necessary for achieving a similar degree of accuracy. A net accuracy gain of 43% was measured when the number of observations varied from 10 to 20 for both mixtures. This gain reached 82% in both cases when n varied from 10 to 50. This supports the optimization of the experimental work in terms of the reduction of sampling. Moreover, the proposed methodology associates a number of experimental observations with a given degree of uncertainty on ITS.

- Finally, the proposed methodology can be generalized to other experimental scientific fields.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Preteseille, M.; Lenoir, T. Mechanical Fatigue of a Stabilized/Treated Soil Tested with Uniaxial and Biaxial Flexural Tests. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 14, 1923–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, D.X.; Houben, L.J.M.; Molenaar, A.A.A.; Shui, Z.H. Mechanical properties of cement-treated aggregate material—A review. Mater. Des. 2012, 33, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preteseille, M.; Lenoir, T. Structural test at the laboratory scale for the utilization of stabilized fine-grained soils in the subgrades of High Speed Rail infrastructures: Experimental aspects. Int. J. Fatigue 2016, 82, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celauro, B.; Bevilacqua, A.; Lo Bosco, D.; Celauro, C. Design Procedures for Soil-Lime Stabilization for Road and Railway Embankments. Part 1—Review of Design Methods. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 53, 754–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoozi, A.A.; Guney Olgun, C.; Firoozi, A.A.; Baghini, M.S. Fundamentals of soil stabilization. Int. J. Geo Eng. 2017, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedarla, A.; Chittoori, S.; Puppala, A. Influence of mineralogy and plasticity index on the stabilization effectiveness of expansive clays. Transp. Res. Rec. 2011, 2212, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirivitmaitrie, C.; Puppala, A.; Saride, S.; Hoyos, L. Combined lime-cement stabilization for longer life of low-volume roads. Transp. Res. Rec. 2011, 2204, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittoori, B.C.S.; Puppala, A.J.; Pedarla, A. Addressing Clay Mineralogy Effects on Performance of Chemically Stabilized Expansive Soils Subjected to Seasonal Wetting and Drying. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2018, 144, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sariosseiri, F.; Muhunthan, B. Effect of cement treatment on geotechnical properties of some Washington State soils. Eng. Geol. 2009, 104, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consoli, N.C.; Vaz Ferreira, P.M.; Tang, C.S.; Veloso Marques, S.F.; Festugato, L.; Corte, M.B. A unique relationship determining strength of silty/clayey soils—Portland cement mixes. Soils Found. 2016, 56, 1082–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horpibulsuk, S.; Miura, N.; Nagaraj, T.S. Assessment of strength development in cement-admixed high water content clays with Abrams’ law as a basis. Geotechnique 2003, 53, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnaid, F.; Prietto, P.D.M.; Consoli, N.C. Characterization of Cemented Sand in Triaxial Compression. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2001, 127, 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenoir, T.; Dubreucq, T.; Lambert, T.; Killinger, D. Safety factor calculation of a road structure with cement-modified loess as subgrade. Transp. Geotech. 2021, 30, 100604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Baldovino, J.J.A.; dos Izzo, R.L.S.; Pereira, M.D.; de Rocha, E.V.G.; Rose, J.L.; Bordignon, V.R. Equations Controlling Tensile and Compressive Strength Ratio of Sedimentary Soil–Cement Mixtures under Optimal Compaction Conditions. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2020, 32, 04019320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiz, R.; Ammenberg, J.; Baas, L.; Eklund, M.; Helgstrand, A.; Marshall, R. Improving the CO2 performance of cement, part II: Framework for assessing CO2 improvement measures in the cement industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 98, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, R.M. Global CO2 emissions from cement production. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2018, 10, 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Huston, M.T. Direct-tensile stress and strain of a cement-stabilized soil. Highw. Res. Rec. 1972, 379, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Consoli, N.C.; Dalla Rosa, J.A.; Gauer, E.A.; dos Santos, V.R.; Moretto, R.L.; Corte, M.B. Key parameters for tensile and compressive strength of silt–lime mixtures. Géotech. Lett. 2012, 2, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MolaAbasi, H.; Khajeh, A.; Semsani, S.N.; Kordnaeij, A. Prediction of Zeolite-Cemented Sand Tensile Strength by GMDH type Neural Network. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2019, 33, 1611–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnos, J.N.; Kennedy, T.W.; Hudson, W.R. Evaluation and Prediction of Tensile Properties of Cement-Treated Materials; Research Report Number 98-8; Center for Highway Research—University of Texas: Austin, TX, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, R.K.; Kennedy, T.W.; Hudson, W.R. Factors affecting the tensile strength of materials. Highw. Res. Rec. 1970, 315, 64–80. [Google Scholar]

- Fedrigo, W.; Núñez, W.P.; Castañeda López, M.A.; Kleinert, T.R.; Ceratti, J.A.P. A study on the resilient modulus of cement-treated mixtures of RAP and aggregates using indirect tensile, triaxial and flexural tests. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 171, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adresi, M.; Khishdari, A.; Ahmadi, A.; Rooholamini, H. Influence of high content of reclaimed asphalt on the mechanical properties of cement-treated base under critical environmental conditions. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2019, 20, 1098–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consoli, N.C.; Foppa, D.; Festugato, L.; Heineck, K.S. Key Parameters for Strength Control of Artificially Cemented Soils. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2007, 133, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consoli, N.C.; Cruz, R.C.; Floss, M.F.; Festugato, L. Parameters Controlling Tensile and Compressive Strength of Artificially Cemented Sand. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2010, 136, 759–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Deng, A.; Jaksa, M. Optimizing micaceous soil stabilization using response surface method. J. Rock. Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2021, 13, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez Muñoz, Y.; Luis dos Santos Izzo, R.; Leindorf de Almeida, J.; Arrieta Baldovino, J.; Lundgren Rose, J. The role of rice husk ash, cement and polypropylene fibers on the mechanical behavior of a soil from Guabirotuba formation. Transp. Geotech. 2021, 31, 100673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LCPC; SETRA. Traitement Des Sols à la Chaux et/ou aux Liants Hydrauliques, 2nd ed.; LCPC: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.; Henry, M.; Opon, J. Exploring the experimental design and statistical modeling of cementitious composite systems using various sampling methods. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 2021, 19, 501–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slebi-Acevedo, C.J.; Castro-Fresno, D.; Pascual-Muñoz, P.; Lastra-González, P. A combination of DOE—Multi-criteria decision making analysis applied to additive assessment in porous asphalt mixture. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2022, 23, 2489–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeagwuani, C.C.; Agunwamba, J.C.; Nwankwo, C.M.; Eneh, M. Additives optimization for expansive soil subgrade modification based on Taguchi grey relational analysis. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2021, 14, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olgun, M. The effects and optimization of additives for expansive clays under freeze-thaw conditions. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2013, 93, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi, M.; Rowshanzamir, M.; Abtahi, S.M.; Hejazi, S.M. Optimization of carpet waste fibers and steel slag particles to reinforce expansive soil using response surface methodology. Appl. Clay Sci. 2017, 142, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Wu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, C.; Shen, X.; Xia, L.; Zang, J. Modeling and optimization of fly ash–slag-based geopolymer using response surface method and its application in soft soil stabilization. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 315, 125723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, D.X.; Houben, L.J.M.; Molenaar, A.A.A.; Shui, Z.H. Mixture optimization of cement treated demolition waste with recycled masonry and concrete. Mater. Struct. Constr. 2012, 45, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longarini, N.; Crespi, P.; Zucca, M.; Giordano, N.; Silvestro, G. The advantages of fly ash use in concrete structures. Inz. Miner. 2014, 15, 141–145. [Google Scholar]

- NF EN ISO 17892-4; Geotechnical Investigation and Testing—Laboratory Testing of Soil—Part 4: Determination of Particle Size Distribution. AFNOR: Saint-Denis, France, 2018.

- NF EN ISO 17892-3; Geotechnical Investigation and Testing—Laboratory Testing of Soil—Part 3: Determination of Particle Density. AFNOR: Saint-Denis, France, 2015.

- NF EN ISO 17892-12; Geotechnical Investigation and Testing—Laboratory Testing of Soil—Part 12: Determination of Liquid and Plastic Limits. AFNOR: Saint-Denis, France, 2018.

- M 145-91; Classification of Soils and Soil–Aggregate Mixtures for Highway Construction Purposes. AASHTO: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- NF P11-300; Classification of Materials for Use in the Construction of Embankments and Capping Layers of Road Infrastructures. AFNOR: Saint-Denis, France, 1992.

- D2487-17; Standard Practice for Classification of Soils for Engineering Purposes (Unified Soil Classification System). ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- NF EN ISO 14688-1; Geotechnical Investigation and Testing—Identification and Classification of Soil—Part 1: Identification and Description. AFNOR: Saint-Denis, France, 2018.

- NF EN 197-1; Cement—Part 1: Composition, Specifications and Conformity Criteria for Common Cements. AFNOR: Saint-Denis, France, 2012; p. 42.

- NF P94-093; Soils: Investigation and Testing—Determination of the Compaction Reference Values of a Soil Type—Standard Proctor Test—Modified Proctor Test. AFNOR: Saint-Denis, France, 2014.

- Castaneda-Lopez, M.A.; Lenoir, T.; Sanfratello, J.P.; Thorel, L. Tensile properties of cement stabilized soils: Experimental data. Rech. Data Gouv. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NF EN 13286-42; Unbound and Hydraulically Bound Mixtures—Part 42: Test Method for the Determination of the Indirect Tensile Strength of Hydraulically Bound Mixtures. AFNOR: Saint-Denis, France, 2003.

- Montgomery, D.C. Design and Analysis of Experiments, 9th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah, A.; Russo, G.; Cuisinier, O. Statistical and Predictive Analyses of the Strength Development of a Cement-Treated Clayey Soil. Geotechnics 2023, 3, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johari, A.; Fooladi, H. Comparative study of stochastic slope stability analysis based on conditional and unconditional random field. Comput. Geotech. 2020, 125, 103707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, R.H.; Montgomery, D.C.; Anderson-Cook, C.M. Response Surface Methodology: Process and Product Optimization Using Designed Experiments, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Viana, F.A.C. A Tutorial on Latin Hypercube Design of Experiments. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2016, 32, 1975–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, V.R. Space-filling designs for computer experiments: A review. Qual. Eng. 2016, 28, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, J.; Welch, W.J.; Mitchell, T.J.; Wynn, H.P. Design and analysis of computer experiments. Stat. Sci. 1989, 4, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, S. Reliability analysis of rock slopes considering the uncertainty of joint spatial distributions. Comput. Geotech. 2023, 161, 105566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, T.; Flanagan, D. doepy 0.0.1. 2023. Available online: https://pypi.org/project/doepy/ (accessed on 29 March 2023).

- Van Rossum, G. Python Tutorial CS-R9526; Centrum voor Wiskunde en Informatica (CWI): Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinney, W. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference (SciPy 2010), Austin, TX, USA, 28 June–3 July 2010; pp. 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabold, S.; Perktold, J. Statsmodels: Econometric and Statistical Modeling with Python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference (SciPy 2010), Austin, TX, USA, 28 June–3 July 2010; pp. 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waskom, M. Seaborn: Statistical data visualization. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mola-Abasi, H.; Khajeh, A.; Naderi Semsani, S. Effect of the Ratio between Porosity and SiO2 and Al2O3 on Tensile Strength of Zeolite-Cemented Sands. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2018, 30, 04018028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedrigo, W.; Núñez, W.P.; Visser, A.T. A review of full-depth reclamation of pavements with Portland cement: Brazil and abroad. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 262, 120540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piratheepan, J.; Gnanendran, C.T.; Arulrajah, A. Determination of c and φ from IDT and Unconfined Compression Testing and Numerical Analysis. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2012, 24, 1153–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preteseille, M. Comportement à la Fatigue des Sols Traités aux Liants Hydrauliques Dans les Plates-Formes des Structures Ferroviaires Pour L.G.V: Modélisations Numérique et Expérimentale de Leur Comportement. Ph.D. Thesis, Ecole Centrale de Nantes, Nantes, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mwumvaneza, V.; Hou, W.; Ozer, H.; Tutumluer, E.; Al-Qadi, I.L.; Beshears, S. Characterization and stabilization of quarry byproducts for sustainable pavement applications. Transp. Res. Rec. 2015, 2509, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consoli, N.C.; Fonseca, A.V.; Silva, S.; Cruz, R.C.; Fonini, A. Parameters controlling stiffness and strength of artificially cemented soils. Géotechnique 2012, 62, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullard, J.W.; Jennings, H.M.; Livingston, R.A.; Nonat, A.; Scherer, G.W.; Schweitzer, J.S.; Scrivener, K.L.; Thomas, J.J. Mechanisms of cement hydration. Cem. Concr. Res. 2011, 41, 1208–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kezdi, A.; Rethati, L. Soil Mechanics of Earthworks, Foundations and Highway Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| V | Varying Factors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curing Time, CT (Days) | Cement Content, CC (%) a | Degree of Compaction, DC (%) b | Water Content, W (%) c | |

| V1 | 7, 28, 90, 180, 360 | 3.0 | 94.0 | 100 |

| V2 | 7, 28, 90, 180, 360 | 2.0 | 96.0 | 100 |

| V3 (ref.) | 7, 28, 90, 180, 360 | 3.0 | 96.0 | 100 |

| V4 | 7, 28, 90, 180, 360 | 4.0 | 96.0 | 100 |

| V5 | 7, 28, 90, 180 | 3.0 | 96.0 | 90 |

| V6 | 7, 28, 90, 180 | 3.0 | 96.0 | 110 |

| V7 | 7, 28, 90, 180, 360 | 3.0 | 98.5 | 100 |

| NT | - | 0.0 | 96.0 | 100 |

| Material | V | NT | 7 Days | 28 Days | 90 Days | 180 Days | 360 Days | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| A | V1 | 0.116 | 0.008 | 0.154 | 0.009 | 0.152 | 0.014 | 0.162 | 0.013 | 0.230 | 0.010 | ||

| V2 | 0.092 | 0.006 | 0.093 | 0.005 | 0.101 | 0.008 | 0.144 | 0.007 | 0.187 | 0.012 | |||

| V3 | 0.140 | 0.019 | 0.151 | 0.009 | 0.176 | 0.010 | 0.226 | 0.003 | 0.215 | 0.031 | |||

| V4 | 0.141 | 0.009 | 0.203 | 0.029 | 0.292 | 0.022 | 0.318 | 0.041 | 0.354 | 0.030 | |||

| V5 | 0.125 | 0.009 | 0.155 | 0.009 | 0.204 | 0.006 | 0.211 | 0.014 | - | - | |||

| V6 | 0.117 | 0.010 | 0.138 | 0.014 | 0.194 | 0.020 | 0.215 | 0.011 | - | - | |||

| V7 | 0.144 | 0.016 | 0.162 | 0.009 | 0.218 | 0.004 | 0.272 | 0.032 | 0.258 | 0.011 | |||

| NT | 0.019 | 0.004 | |||||||||||

| B | V1 | 0.105 | 0.011 | 0.135 | 0.009 | 0.179 | 0.019 | 0.198 | 0.014 | 0.264 | 0.013 | ||

| V2 | 0.085 | 0.004 | 0.107 | 0.012 | 0.157 | 0.007 | 0.195 | 0.001 | 0.225 | 0.004 | |||

| V3 | 0.120 | 0.007 | 0.174 | 0.008 | 0.210 | 0.014 | 0.261 | 0.013 | 0.313 | 0.008 | |||

| V4 | 0.149 | 0.001 | 0.199 | 0.010 | 0.269 | 0.007 | 0.317 | 0.018 | 0.319 | 0.006 | |||

| V5 | 0.108 | 0.004 | 0.140 | 0.018 | 0.190 | 0.009 | 0.252 | 0.010 | - | - | |||

| V6 | 0.101 | 0.002 | 0.137 | 0.005 | 0.210 | 0.009 | 0.230 | 0.021 | - | - | |||

| V7 | 0.126 | 0.002 | 0.172 | 0.017 | 0.253 | 0.008 | 0.306 | 0.017 | 0.344 | 0.007 | |||

| NT | 0.010 | 0.001 | |||||||||||

| CSS | Source of Variation | Degrees of Freedom | SS (×10−4) | Fo | p-Value | Percent Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Log10 CT | 1 | 1396.7 | 218.7 | 4.1 × 10−27 | 44.5 |

| CC | 1 | 1514.0 | 237.0 | 2.3 × 10−28 | 48.2 | |

| DC | 1 | 225.6 | 35.3 | 3.9 × 10−8 | 7.2 | |

| W | 1 | 4.7 | 0.74 | 0.39 | 0.1 | |

| Error | 102 | 651.5 | ||||

| B | Log10 CT | 1 | 3381.3 | 770.2 | 4.6 × 10−49 | 77.3 |

| CC | 1 | 677.6 | 154.3 | 4.6 × 10−22 | 15.5 | |

| DC | 1 | 311.7 | 71.0 | 2.6 × 10−13 | 7.1 | |

| W | 1 | 2.7 | 0.62 | 0.43 | 0.1 | |

| Error | 101 | 443.4 |

| Source of Variation | Min. Level | Intermediate Level(s) | Max. Level | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT | Log10(7) [−1.00] | Log10(28) [−0.30] | Log10(90) [+0.30] | Log10(180) [+0.65] | Log10(360) [+1.00] |

| CC | 2.0 [−1.00] | 3.0 [0.00] | 4.0 [+1.00] | ||

| DC | 94.0 [−1.00] | 96.0 [+0.11] | 98.5 [+1.00] | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castaneda-Lopez, M.; Lenoir, T.; Sanfratello, J.-P.; Thorel, L. Data-Driven Prediction of Cement-Stabilized Soils Tensile Properties. Infrastructures 2023, 8, 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures8100146

Castaneda-Lopez M, Lenoir T, Sanfratello J-P, Thorel L. Data-Driven Prediction of Cement-Stabilized Soils Tensile Properties. Infrastructures. 2023; 8(10):146. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures8100146

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastaneda-Lopez, Mario, Thomas Lenoir, Jean-Pierre Sanfratello, and Luc Thorel. 2023. "Data-Driven Prediction of Cement-Stabilized Soils Tensile Properties" Infrastructures 8, no. 10: 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures8100146

APA StyleCastaneda-Lopez, M., Lenoir, T., Sanfratello, J.-P., & Thorel, L. (2023). Data-Driven Prediction of Cement-Stabilized Soils Tensile Properties. Infrastructures, 8(10), 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures8100146