1. Introduction

The epistemological position of digital modeling software in representing existing buildings seems to differ fundamentally from its position in the design of new buildings. In the former case, a referent building exists, and software in combination with remote-sensing technology can be used to achieve a precise and efficient form of documentation [

1]. In the latter case, there is a prevailing assumption that the act of architectural representation, particularly when executed iteratively, can be used as a designerly mechanism for generating new knowledge [

2]. Thus, the act of digitally modeling existing buildings appears to prioritize knowledge display over the knowledge production that is more typical of new-building design. In a wider context, ref. [

3] articulates the distinction between knowledge display and knowledge production. For [

3], knowledge display is associated with a concealment of the decisions and processes on the basis of which it was produced. Similarly, ref. [

4] introduce a distinction between “models of” and “models for,” wherein the former are concerned with representations that map a presumably objective reality, and the latter are concerned with how models and their interrelationships “serve an epistemic purpose beyond depiction.” Traditional applications of BIM for existing buildings typically function as devices for knowledge display, in that they present geometrically resolved models while concealing the interpretive decisions made during model construction. In contrast, the methodology proposed in this paper leverages BIM for knowledge production by directly exposing ambiguity within models.

Conventional uses of Building Information Modeling (BIM) software for representing existing buildings tend to treat architectural representation as depiction, with a heavy emphasis on achieving precision and geometric accuracy, resulting in “models of” buildings [

5]. Nevertheless, digital models of existing buildings are not neutral containers of information but are instead the consequence of representational acts structured by context [

6]. To paraphrase [

7], architects do not make buildings; they make digital models of buildings, and interpreting those models is not the same as interpreting the buildings to which they refer [

8]. It follows that digital models of existing buildings should not be viewed as transparent or neutral reflections of reality, but as situated constructs that actively shape what can be seen, how what can be seen is understood, and whether certain dimensions of knowledge are foregrounded, marginalized, or actively omitted. In the case of BIM, we suggest that its conventional use encourages a form of

epistemic closure, or in other words, a false sense that the model both constitutes and represents a complete and finished reality.

Rather than reinforcing that conventional emphasis, this paper argues for BIM-based practices that encourage interpretive openness–where relationships between views become the source of architectural meaning, and where a BIM model’s role expands its core function (namely, the efficient production of coordinated documentation) to encompass active and critical inquiry. In this way, existing-building BIM is positioned as a process that can approach the productive ambiguity of new-building design referred to above. The primary implication is that BIM’s conventional emphasis on geometric consistency and epistemic closure can be productively disrupted to foreground relational ambiguity, which in this context means highlighting uncertainties between views. This has the effect of transforming BIM into a tool for epistemic resilience, which we define as a model’s capacity to sustain multiple, conflicting interpretations without collapsing into false certainty.

Our approach differs from dominant trends in existing-building BIM research, which generally focuses on the problems of efficiency and accuracy in automated reconstruction [

9,

10]. Instead, this paper’s emphasis is on knowledge effects as understood to derive from a plurality of representational modes. These effects may align with forms of sociopolitical and economic resilience, particularly in contexts where representational control is contested, as shown, for example, in the work of critical cartography [

11,

12]. More specifically, representational methods that foreground ambiguity can enable multiple narratives, which are critical in contexts where histories are contested [

13]. Thus, the method introduced here offers a means for participatory and pluralistic architectural discourse. In this context, we see our proposed method as potentially valuable for investigative actors: heritage conservationists, architectural historians, and researchers generally. Unlike a professional BIM user in the new-building industry, these investigative actors do not necessarily measure the effectiveness of their methods by speed or efficiency: they can value the visualization of conflict and subjectivity as methodological ends in themselves.

While the method we describe prioritizes the need for critical interpretation over computational efficiency, the outcomes also carry practical implications for the creation of “digital twins” for existing structures. Specifically, the concept of epistemic resilience can be positioned practically as a strategy for managing uncertainty in contexts where documentation is often incomplete or conflicting. By foregrounding ambiguity rather than working to conceal it, our method can help to expose potentially costly assumptions while providing a more nuanced representation of a building’s complex history.

1.1. Reciprocal Relationships

Like other representational artifacts, digital models function as epistemic tools, mediating architectural knowledge by means of culturally specific representational practices [

2]. Existing buildings participate in architectural discourse through being represented in artifacts like drawings and models. These drawings and models trigger and sustain an interpretive process of conceptual negotiation [

14]. This interpretive process is neither simple nor immediate [

15]. It involves,

inter alia, the mental construction of spatial relationships that may not be explicitly depicted in drawings or models. An example may be found in the paired plan and section drawings of an existing building (

Figure 1).

The two drawings (plan and section) reciprocally interpret each other in contributing to the mental formation of spatially coherent understandings. This complementary relationship is precisely what [

16] identify as “reciprocity and … [mutual] dependence.” As [

7] emphasizes, orthographic projections are “never exhaustive”–they always invite a kind of mental synthesis or what is referred to in this paper as

reconciliation. Reconciliation is fundamentally generative, reflecting what [

17] describe as the “hopeful possibility of plan, section and elevation being … reversible.” The transformative work involved in mentally relating drawings and the thoughts they initiate enables what [

18] describe as “allowing a three-dimensional presence to form in the viewer’s mind” as architectural understanding unfolds.

The idea of mentally reconciling projections (e.g., orthographic views) is linked to the capacity of representation to absorb and proliferate “ambiguities and inconsistencies” [

7]. This assertion goes beyond any technical concern. It assumes that different architectural representations, such as orthographic views or perspectives, will be differently relevant to diverse stakeholders, and that processes of mentally relating representations into a coherent whole will operate in specific and culturally grounded contexts, perhaps even idiosyncratically. Reconciliation is also not something that can trivially be achieved by presenting photorealistic views of buildings or immersive walkthroughs, both of which are inseparable from perspectivism [

17]. Instead, manual reconciliation is contingent on the idea that architecture and its representations operate on a level that “barely initiate[s] thought” [

14]. For these reasons, architectural representation must be skeptical of any attempt to provide totalizing views, or to remove or sideline the importance of mental reconciliation as a process.

1.2. BIM’s Effects of Knowledge Production for Existing Buildings

Choosing to engage BIM in existing-building representation implies acceptance of a way of organizing work, the knowledge-effects of which include increased specialization [

19]. Moreover, consistency among representations–precisely, BIM’s default position–is a long-recognized criterion for information-visualization validity [

20,

21]. Nevertheless, digitally modeling an existing building is an interpretive act [

22,

23], one that begins with a choice of approach, e.g., between geometric, parametric, or semantic approaches, or between parametric, geometrically accurate, or knowledge-generating ones [

24,

25,

26]. Moreover, digital modeling inherently involves tacit judgment [

6,

27]. As such, digital modeling considered broadly has the capability to operate as an ambiguity-foregrounding method accommodating multiple knowledge domains.

BIM’s most obvious and significant knowledge implication lies in the software’s ability to provide an arbitrarily large number of consistent, coordinated representations of a geometrically complex reality, e.g., a building. This concept is referred to here as

automatic reconciliation to emphasize its difference from the manual process of mental reconciliation described above. Automatic reconciliation takes place without any active engagement by the modelmaker; it is simply a consequence of BIM’s central model being made visible by means of distinct projections (e.g., plan and section). It is in part due to this ability that BIM derives its obvious utility within architectural and engineering practice in support of new-building design. What in a pre-BIM context constituted a tedious process of manually coordinating two-dimensional drawings (e.g., plans with sections) becomes, within BIM, a banal consequence of the software’s ontology. In the context of new-building design, the omission of this manual coordination process has had clear positive effects on production and efficiency [

28].

So much is obvious within contemporary practice as it relates to the design of

new buildings. However, BIM’s relevance to representing

existing buildings remains an active and contested area of research [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. In large part, research in this area examines distinctions between BIM’s ability to support objective documentation (e.g., through point-cloud scanning or photogrammetry) and semantic enrichment (i.e., the addition of meaningful relationships to a model). For example, ref. [

35] introduce a distinction between “black box” and “white box” modeling approaches, in which the former treats the referent building as a coherent structure of scanned points modeled in 3d space, and the latter treats the referent building as a consequence of parametrically informed modeling decisions, with the potential to incorporate predefined element libraries. These two approaches result not only in two distinct kinds of models but in two different affordances for conceptually understanding the architecture. Similarly, ref. [

36] raise the possibility of different model construction processes leading to differing interpretations, i.e., “different modes of critical re-reading.” Model construction processes are further complicated in the case of demolished buildings, where a distinction arises between a “theoretical” model, that is, a model based on documentary sources, and an “as-built” model representing field-verified geometry [

37]. That a building no longer physically exists means that any verification of its elements introduces a unique kind of ambiguity, i.e., among interpretations of an incomplete or internally contradictory documentary record [

38,

39]. Failure to observe the distinction between document-based and field-based models can result in reduced applicability to applications like structural health monitoring [

37].

Fundamentally, BIM’s hierarchical, component-based knowledge structure risks conflict with open-ended, interpretive approaches to representing and modeling built heritage. In part, this is simply because BIM’s ontology, to the extent that it depends on parametric relationships and predefined elements, can struggle to capture the formal and material idiosyncrasies of existing buildings [

40]. The epistemological consequences arise in at least two ways. First, there are uncertainties regarding BIM standardization in heritage and conservation contexts [

41]. Second, there is a risk to marginalizing or excluding culturally specific practices, e.g., construction and living patterns that defy BIM’s expectations for clarity of organization and geometric consistency [

42].

1.3. Cultural Assumptions and Epistemic Bias in BIM

Existing-building BIM aims for efficiency in producing complete, accurate, and comprehensive models. These aims have the effect of prioritizing dominant knowledge systems, i.e., the standards of the AEC industry [

43]. Such standards are often positioned as epistemologically neutral, aimed at making interoperability between software platforms “seamless” [

44]. For example, consider how an existing masonry building with sagging floors or out-of-plane walls could become “homogenized” in BIM. To maintain geometric consistency, a modelmaker might simplify observational data into the level planes and vertical walls encouraged by the software’s internal logic [

1,

10]. Such an approach would result in an “interpretive homogenization” where the building’s idiosyncrasies are flattened into a standard, industry-compliant representation. Even apparently objective standards such as IFC may carry specific Western, industry-centered logics that risk marginalizing nuanced or conflicting understandings of space [

45,

46]. For example, the IFC entity IfcWall refers to “a vertical construction that may bound or subdivide spaces” [

47]. This apparently straightforward definition assumes dichotomies (e.g., container versus contained) and hierarchies (e.g., subdivisions) that arguably make more sense when applied to buildings like factories and offices rather than to nomadic shelters, reed mudhifs, or cave housing. Within a context informed by sharp dichotomies and clear hierarchies, BIM’s major conceit is that ambiguity and conflict cannot exist, or rather that alignment and coordination between representations of the model are incontestable because all views refer to a single central model. This is the case for orthographic and perspective views as well as exploded or “displaced” views (

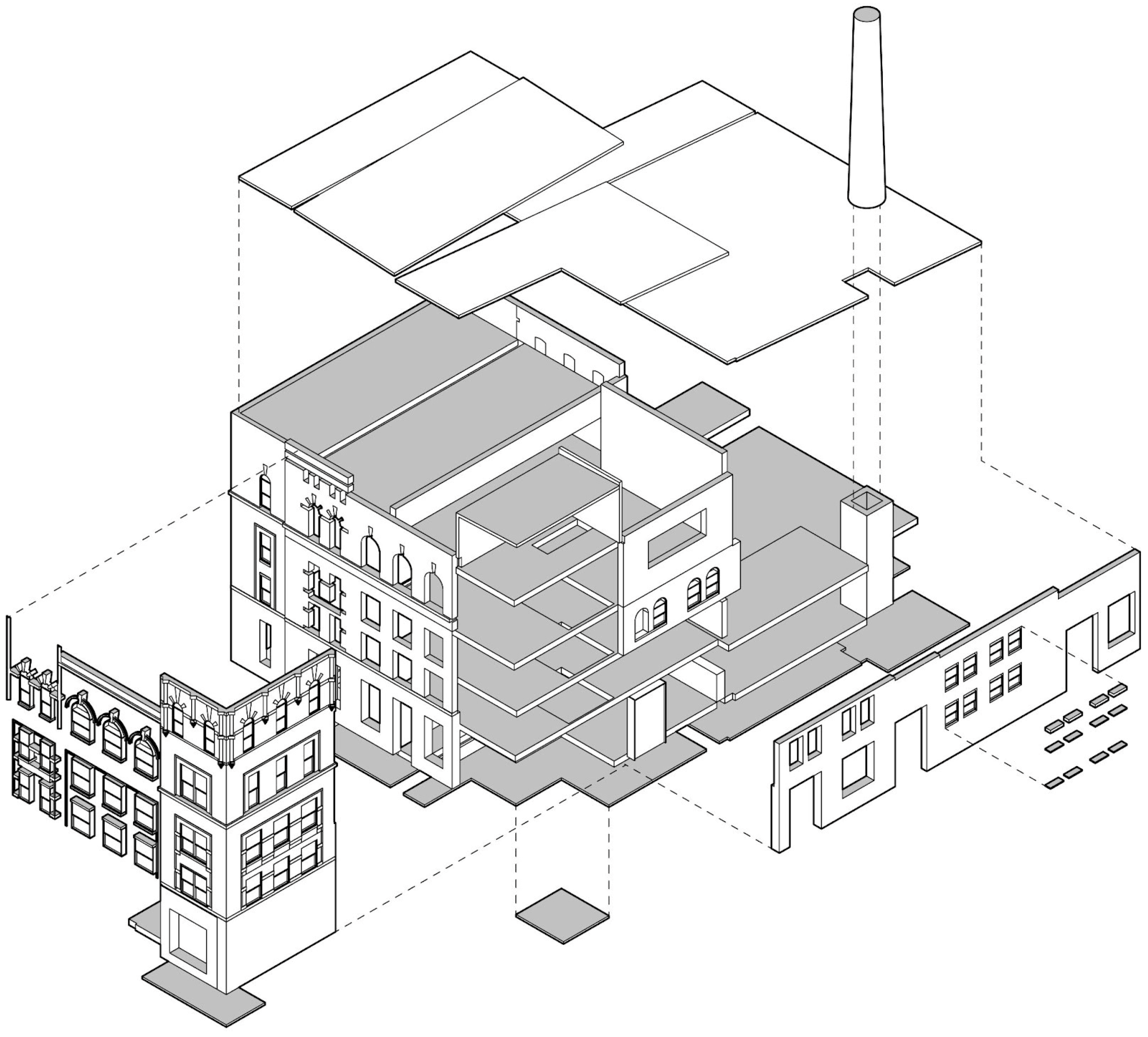

Figure 2).

The central-model assumption guarantees alignment of BIM with Cartesian frameworks reflecting a Western privileging of geometric objectivity, marginalizing non-metric knowledge systems [

17]. Yet even apparently neutral concepts such as geometric accuracy have different meanings, different degrees of relevance, and different extents of subjectivity within different cultural contexts [

14,

48].

1.4. Devices of Reciprocity in BIM

Apart from the software’s ontological focus on automatic reconciliation, BIM relies on certain formal mechanisms to explicate reciprocal relationships. These mechanisms, referred to here as devices of reciprocity, may be categorized into model-based devices and sheet-based devices. The categories reflect important technical and conceptual differences between two modes of producing modeled or drawn information. Model-based devices include coordinate systems, reference planes, level lines, and parametric relationships that are explicitly coded to relate parameters to modeled form. Sheet-based devices identify or relate views to each other. While both model-based and sheet-based devices are designed to streamline automatic view coordination, they have the side effect of constraining the modelmaker’s ability to engage a model’s spatial ambiguity. The following section outlines a method for repurposing these mechanisms to prioritize manual reconciliation as a site of critical inquiry.

2. Materials and Methods

This section of the paper highlights a specific method for problematizing reciprocal relationships in a case-study BIM model. The method is explicitly not designed as an automated process but as a manual workflow intended to introduce subjective and critical ambiguity. In this way, the method is not positioned solely as a technical process but as a philosophical reorientation of how meaning is constructed through modeling.

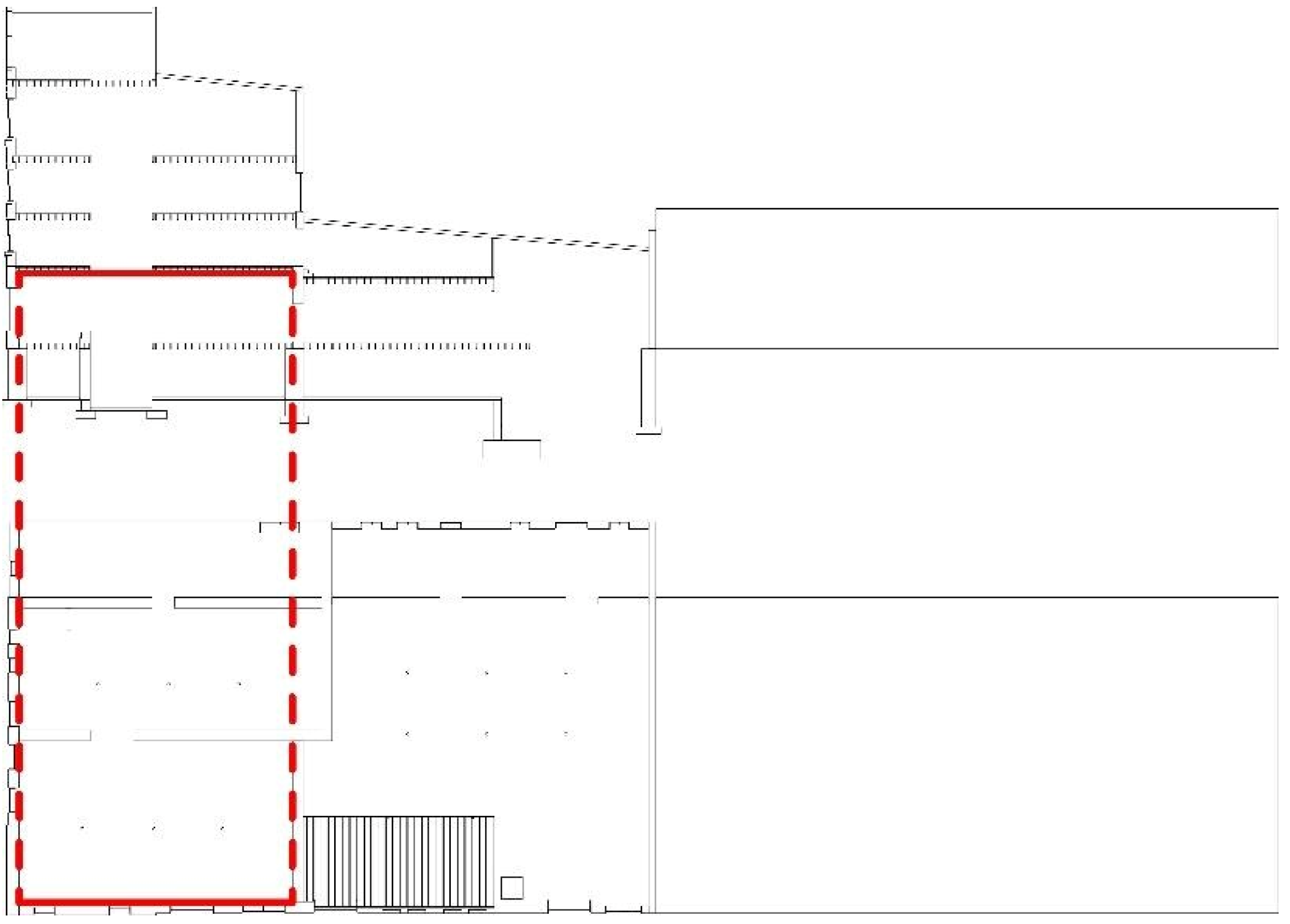

The project relies on Autodesk Revit 2026 to particularize its argument. However, the underlying logic broadly reflects capabilities that are inherent to BIM software generally (e.g., ArchiCAD, Vectorworks): namely, the software’s automated reconciliation of orthographic projections derived from a parametrically driven database. We consider a BIM model of a recently demolished building in Winona, Minnesota (USA), constructed by this paper’s corresponding author (

Figure 3). The case study is selected as an example of the kind of building susceptible to our method: that is, any one where some form of interpretive friction exists between as-built reality, traditional documentation, and digital model. The construction of such existing-building models implicates multiple sources of evidence [

38]. In this case, the building’s demolition introduces a specific kind of interpretive ambiguity, because it is no longer possible to conduct the kind of field verification or validation that an existing building would present.

2.1. Construction of Reference Frame

To counter BIM’s default automation of view reconciliation, this method introduces an intentional layer of ambiguity and relationality by foregrounding reciprocal relationships between orthographic views. The ambiguous nature of orthographic views may be highlighted by deliberately juxtaposing and superimposing them, calling their presumed existence as independent registers of the model into question. Stated somewhat differently, reciprocal relationships between views can be

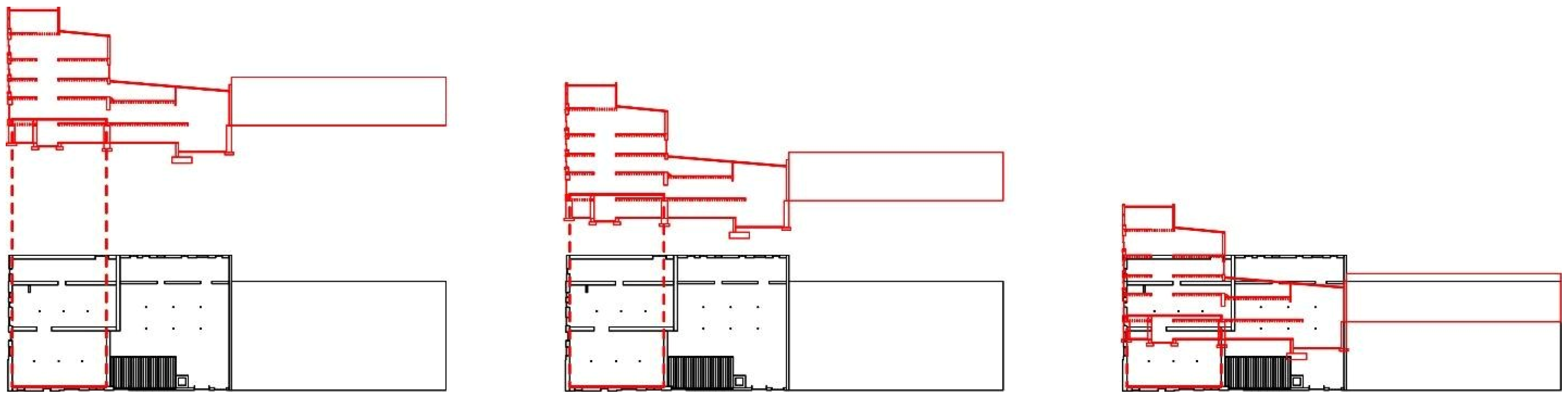

problematized: that is, relations between views can be considered as an open question requiring active investigation, rather than as a fixed, automatic linkage. Our method establishes relationships graphically and then positions views relative to that drawn relationship. More specifically, we begin by identifying a possibly critical relationship, such as between two orthographic views. We then graphically deploy an armature or frame that provides a kind of intentional superimposition between those views. The resulting superimposition is then open to a process of manual reconciliation. To illustrate, suppose that a rectangular armature or frame

f is produced in a Revit sheet, and that

f is understood to signify a reciprocal relationship between two graphic elements positioned, respectively, at a and b (

Figure 4).

f’s rectangular frame and its use of dashed lines respond to the reciprocity mechanisms described above. The frame provides a fixed reference against which misalignment can be measured. Dashed lines, as non-material indicators of spatial relationships, build upon conventions of projection: they indicate what [

49] calls an “imaginal joint between two realms,” i.e., the graphic elements positioned at a and b. For example, paired plan and section views can be positioned at a and b, aligned positionally and at a consistent scale to emphasize formal and spatial relationships that exist between the two views.

Figure 5 illustrates how

f can emphasize a formal relationship between a space as it appears in plan and the same space as it appears in section.

The premise of

Figure 5 is that the reference frame

f initiates the possibility of a meaningful visual relationship between views. Once the frame is in place, the first view (plan or section) is placed relative to f, and then the second view (section or plan) is selected and positioned relative to the first, using

f as a guide.

There is no reason that f needs to remain an inert or fixed element. Instead, like other elements in Revit–or in BIM software generally–f could incorporate parameters, enabling variation in visible features such as proportion, position, and size. More specifically, f may be implemented as a parametric family; its dimensions (length, height) and position on the sheet controlled by user-defined parameters. The crop regions of the plan and section views may be manually aligned and constrained to its edges. This technique effectively transforms the sheet into a dynamic modeling environment, allowing f to become a sheet-based device for explicating reciprocal relationships.

Adjusting the parameters enables iterative exploration of spatial ambiguity as the individual views become visually superimposed to a greater or lesser extent (

Figure 6).

Traditional documentation relies, at least in part, on the visual juxtaposition of views–that is, placing plan and section side-by-side to encourage the mental construction of spatial relationships. In contrast, this method utilizes superimposition to force a collision of spatial information. By parametrically reducing f’s vertical dimension, the modelmaker collapses the orthogonal distance that typically separates these views. Critically, this transition is not merely graphical; it causes a shift from observation to active resolution of visual conflict. To state this idea somewhat more precisely, when the constituent views are separated and visually juxtaposed in the conventional manner, the modelmaker can rely on BIM’s automatic reconciliation, implicitly trusting that the software has coordinated the model geometry to produce each view. However, as the modelmaker compresses f vertically, and the views increasingly overlap (superimposition), this implicit trust is disrupted by visual interference. Lines belonging to the floor plan overlap and intersect with lines in the section, leading to a visually dense mesh of information that cannot be passively read as reflecting certain knowledge. In turn, this requires that the modelmaker engage in manual reconciliation to mentally disentangle plan from section. In this way, superimposition acts as a heuristic device: by obscuring the easy readability of plan and section, it discloses latent logics that connect them to each other.

As an information visualization strategy, visual superimposition is conventionally understood to have certain advantages, such as efficiency of comparison within a shared visual space, as well as apparent disadvantages, notably occlusion and clutter [

50,

51]. The iterative approach to overlapping in

Figure 6 inverts those conventional assumptions. In this case, visual ambiguity is not presented as an obstacle to resolve but as a deliberate visual provocation. By parameterizing visual superimposition, the method makes new demands on interpretive labor, i.e., demanding active interpretation rather than passive consumption.

2.2. Expanding to Other Views

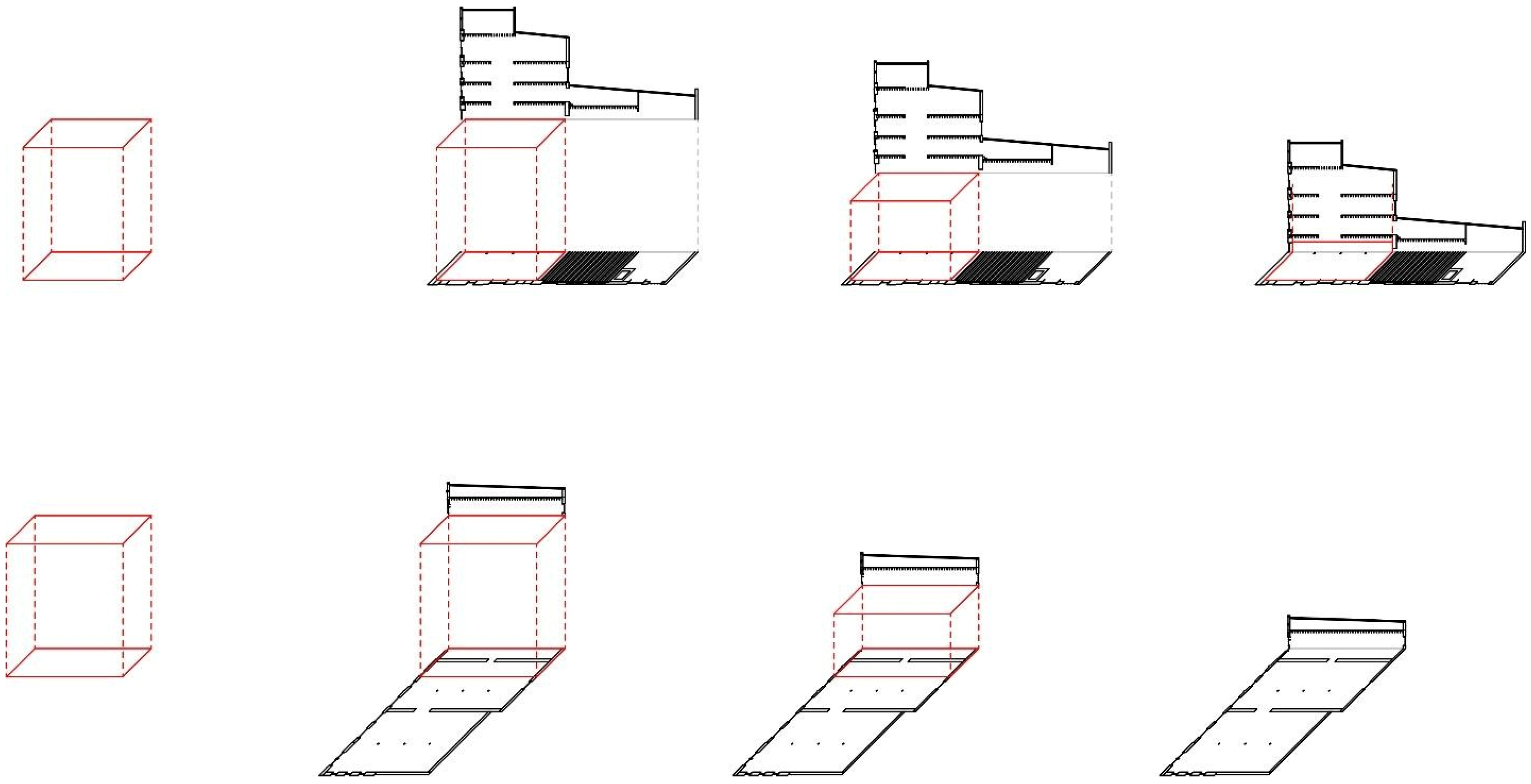

A similar approach can be followed using other views. Suppose that instead of addressing reciprocal relationships between plan and section, relationships are to be emphasized between a section and an oblique projection (

Figure 7). A volumetric reference frame,

f ’, establishes the possible relationship; views are placed in alignment with

f ’. Parametric adjustments to

f ’ allow for variable investigation of the reciprocal relationships between the section and the oblique.

Introducing reference frame f has the effect of focusing modelmaker attention on a reciprocal relationship that exists between two views. This shift in prioritization adds an important function to BIM’s representational capabilities. Rather than treating the central model as the primary source of knowledge, this approach recognizes the epistemological value of relationships between views. Consequently, understanding emerges from the active process of establishing important relationships using reference frame f and then attaching views, rather than simply deriving individual views from a central model.

3. Results

This method challenges BIM’s default prioritization of geometric consistency by foregrounding dynamic relationships between views, such as plan-section reciprocity. A conventional set of drawings, with its focus on clearly distinct, separated views, implies a singular, coordinated reality. In contrast, variably superimposed views as discussed here lead to an ambiguity demanding interpretive labor. Reference frame

f actively highlights relationships between different views rather than treating them as isolated derivatives of the central model. By parameterizing the reference frame, users can dynamically adjust the visual proximity and overlaps between views (as shown in

Figure 6). Overlapping views can highlight contested spatial relationships. The visual ambiguity generated by the superimposition of views functions as a mechanism for knowledge production by resisting what we call epistemic closure.

Our approach acknowledges two fundamentally distinct aspects of BIM. First, BIM centers an underlying database containing information susceptible to meaningful (building-related) queries. Second, BIM provides a mechanism for producing meaningfully useful “views” of the information in that database. Conventionally, those “views” take the form of individual orthographic projections or tabular displays (e.g., room finish schedules). Simply, our method manipulates BIM’s viewing mechanism to uniquely reveal the qualities of information in the database. Our manipulation, taking the form of visual superimposition, generates new knowledge in two ways. First, it demands the capacity of spatial synthesis from viewers. That is, visual overlap forces a simultaneous perception of section and plan, confounding the viewer’s ability to reconcile the building planimetrically. Vertical readings (e.g., of height, daylight, and structure) must be directly tested against the floor plan. Second, in a related way, superimposition promotes a kind of relational visibility. By utilizing f’s parametric controls to overlap views, the modelmaker can identify and visually problematize spatially critical relationships. Conflicts and misalignments, along with unexpected but latent relationships (e.g., between the structural grid and the spatial enclosure), not obvious in isolated views, can become apparent in the form of visual interference.

This shift from static to dynamic representation creates new cognitive challenges, e.g., in the need to interpret visually overlapped drawings. Ambiguity is increased at the expense of clarity and objectivity, inviting contemplation. That is, the method intentionally sacrifices efficiency for deeper engagement in the form of active disambiguation, i.e., manual reconciliation. In its shift from defining individual views to establishing relationships, the workflow encourages new kinds of critical thinking about spatial meanings. Rather than assuming spatial ambiguity must always be resolved, the method encourages conflicting interpretations, thereby calling into question hidden frameworks structuring architectural knowledge (e.g., Cartesian systems). These trade-offs between efficiency and engagement challenge BIM’s conventional assumptions of consistency, stability, and fidelity to referent geometry.

The method identifies the concrete problem of

source ambiguity within existing-building model construction, namely, that such models implicate multiple sources of evidence, typically including drawings or photographs alongside some form of field verification [

38]. As a recently demolished building, the Winona case study permits no field verification whatsoever, complicating the concrete issue of source ambiguity, and opening space for our method to play an important role. This attitude toward ambiguity engages critically with uncertainty visualization, a well-established concern in heritage studies [

38,

39]. Uncertainty visualization conventionally assumes that ambiguity is a consequence of incomplete data, and that better tools will result in increasingly accurate and comprehensive representations of a fixed referent. By contrast, the method proposed here rejects the possibility of a fully knowable referent building. Superimposition, with its inherent occlusion and clutter [

50,

51] demands active interpretation and departs from a search for technical certainty, opening new space for multiple voices and contested histories. Undoubtedly, similar methods could be implemented in other (non-BIM) software. However, the method described here is notable, insofar as by working within the BIM environment, it effectively subverts BIM’s inherent drive for clarity from within. The method uses BIM’s own tools against its default tendencies.

The method’s interpretive flexibility aligns with a broader sociopolitical context. The flexibility that comes with ambiguity means that the method is open to shifting cultural contexts, and treating ambiguity as generative gives new support to developing pluralistic narratives. Expanding opportunities for different forms of knowledge production also implies an opportunity for improving a diversity of voices and constituents, i.e., foregrounding contested or community-reclaimed narratives. Relational ambiguity in BIM is thus able to disrupt conventional workflows; the implications extend beyond technique, with a potential to redefine BIM’s cultural role. Nevertheless, while this method offers new opportunities for critical engagement, it will certainly be less efficient in practice, requiring a level of interpretive labor that challenges typical workflows.

Ultimately, the method demonstrates that BIM’s value in existing-building representation extends beyond its conventional commitment to the efficient production of geometrically consistent and coordinated views. By parametrically enabling the collision and overlap of views, BIM can become a tool for epistemic resilience, where the difficulty of reading the drawing leads to a deeper engagement with the referent, i.e., the building itself.

Practical Implications

Renovation projects are complex, and risk management is essential to success [

52]. Various methods exist to manage risk in renovation projects [

53,

54]. The method proposed here, precisely because it is idiosyncratically capable of highlighting ambiguity, provides a unique mechanism for anticipating expensive errors. For example, consider a hypothetical retrofit of an existing masonry structure with an out-of-plane wall. A standard BIM workflow would model the wall as a vertical element, consistent with software constraints. The resulting floor plan would be geometrically consistent with plan measurements, but epistemically false with respect to the existing as-built conditions. Consequently, precision interventions (i.e., renovations) made on the basis of the plan would inevitably conflict with on-site irregularities. Because the plan and section appear perfectly coordinated by the software, the modelmaker (and the retrofit contractor) may not realize the wall is out-of-plane. The software’s drive for consistency would thereby “mask” spatial uncertainty, concealing a physical risk by a digital expediency. In contrast, our proposed method enables a wall’s footprint to be visually superimposed, to varying degrees, with its sectional projection. The resulting visual interference–essentially, a misalignment of lines–would not offer a geometric solution but would instead signal a site for further inquiry. Such visual interference calls upon a modelmaker to manually reconcile plan and section, transforming a potential source of expensive error into an opportunity for critical attention.

The same issue can arise with the use of point-cloud scanning to produce “as-built” BIM models, as the conversion from a point cloud to a functioning BIM model relies largely on manual processes involving subjective judgment [

9,

10]. Similarly, ref. [

55] remark that the process of “twinning” an existing building demands interpretative labor. Moreover, because contemporary renovation and adaptive reuse projects are characterized by the presence of diverse, often conflicting constituencies (e.g., architects, engineers, community members, historians, and clients), a robust and well-informed decision-making process is necessary to disclose, examine, and weigh comparative or conflicting knowledge claims. The method described here could inform this process alongside other established means [

56].

While traditional BIM workflows in the new-building industry are characterized by design and construction phases, our method is firmly situated in the investigative and pre-design phases of existing-building projects (e.g., conservation or adaptive-reuse work). It aims to provide opportunities for investigative actors to examine conflicts before decisions are solidified into production-oriented BIM models. Similarly, in contrast to in-built mechanisms for interference checking [

57], our method does not aim to automatically identify interfering or “clashing” elements within a model. Instead, it attempts to focus modelmaker attention on the inevitable frictions that arise when software’s default assumptions are tested against built reality.

4. Discussion

This paper has identified a problem, namely, that BIM’s native automated reconciliation in existing-building representation has the effect of prioritizing efficiency over critical interpretation. As a solution, the paper proposes a computational approach aimed at foregrounding relationships between views rather than relying on automatic reconciliation between independent views. The implication is that BIM’s role will expand as a generative tool for architectural knowledge. The proposal is not to abandon BIM’s obvious strengths in coordination or accuracy, but rather to suggest that interpretive ambiguity can be meaningfully introduced in a BIM workflow.

It is essential to distinguish this paper’s approach from routine BIM tasks such as clash detection or cross-disciplinary coordination. These routine tasks necessarily seek to resolve conflicts in pursuit of a singular geometric truth. By contrast, the approach described here seeks to preserve and indeed to amplify conflict as a site of investigative work. To state this idea differently, BIM’s value in routine practical contexts is largely a consequence of its efficiency in providing possibilities for reconciliation. But BIM-based reconciliation is always of a particular kind, in that it reinforces the idea of an unambiguous and universally understood representation, rather than opening space for the kinds of contradictions, conflicts, and gaps that prompt productive and critical interpretation. By calling BIM’s knowledge structure into question, this paper acknowledges BIM’s efficiency in the routine tasks of reconciliation while arguing that this efficiency may inadvertently minimize the knowledge-production effects inherent in reciprocal relationships. By problematizing those relationships–in fact, by leveraging BIM’s capacity for representation–intentional ambiguity may be introduced, leading to epistemological gaps that invite nuanced interpretations. The intent is for ambiguity to support new forms of epistemic resilience, countering the possibility of historical oversimplification, and opening space for otherwise marginalized voices.

While much of the current literature in existing-building BIM focuses on automated reconstruction [

9,

10], we offer an original approach through an intentional subversion of automation. In our view, it is precisely the removal of the modelmaker’s manual interpretive labor (as promised by automation) that constitutes a risk to both knowledge production and critical inquiry. Also, unlike uncertainty visualization methods [

38,

39] that often rely on color-coding or other forms of visual labeling, our approach is original in using parametrically driven superimposition to generate visual interference, in turn demanding manual reconciliation. Finally, by using Revit’s sheets as active sites for investigation instead of as simple registers of a model, we use the software’s own internal logic to critique its tendency toward epistemic closure.

The method leaves pragmatic questions unanswered. As suggested above, future research could proceed to develop plugins and addons aimed at expanding BIM’s representational capacities. The implication is for a new class of plugins, not for automation and clash detection, but for narrative layering, annotation, and the visual management of interpretive ambiguity directly atop the coordinated model. Future research could also examine how relational workflows could be adapted to different BIM platforms (i.e., other than Revit) and to varying modelmaker competencies.

There are methodological implications for architectural and engineering pedagogy. Students can deepen their understanding of BIM’s capabilities in critical modeling through exposure to ambiguity-aware workflows. Pedagogy should emphasize the importance of relationships and narrative multiplicity alongside practical needs for documentary clarity. Teaching strategies need not be aimed at selecting the best or most clearly explanatory individual views in a BIM project, as is typical, but rather at identifying critical relationships that can be visually problematized. Applications in history, conservation, and archaeology could similarly benefit from a workflow that actively engages ambiguity and conflict.

The method proposed here demonstrates that BIM’s tendency toward epistemic closure can be resisted through deliberately ambiguous and relational view configurations. This adds value both practically and epistemically. In a practical sense, the method identifies spatial discrepancies and archival inconsistencies that would otherwise be obscured by BIM’s internal logic. Epistemically, the method transforms a BIM model from its default position of automated certainty into a mechanism for active investigation. The method thereby “reframes” BIM from being a production-oriented document generator into a tool for critical inquiry. This is particularly important in contexts where multiple narratives may coexist. By sacrificing efficiency for investigative rigor, the method proposed here empowers conservationists, historians, and architects to leverage contemporary digital tools to disclose productive uncertainties of the existing built environment.