Integrating Physics-Based and Data-Driven Approaches for Accurate Bending Prediction in Soft Pneumatic Actuators

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

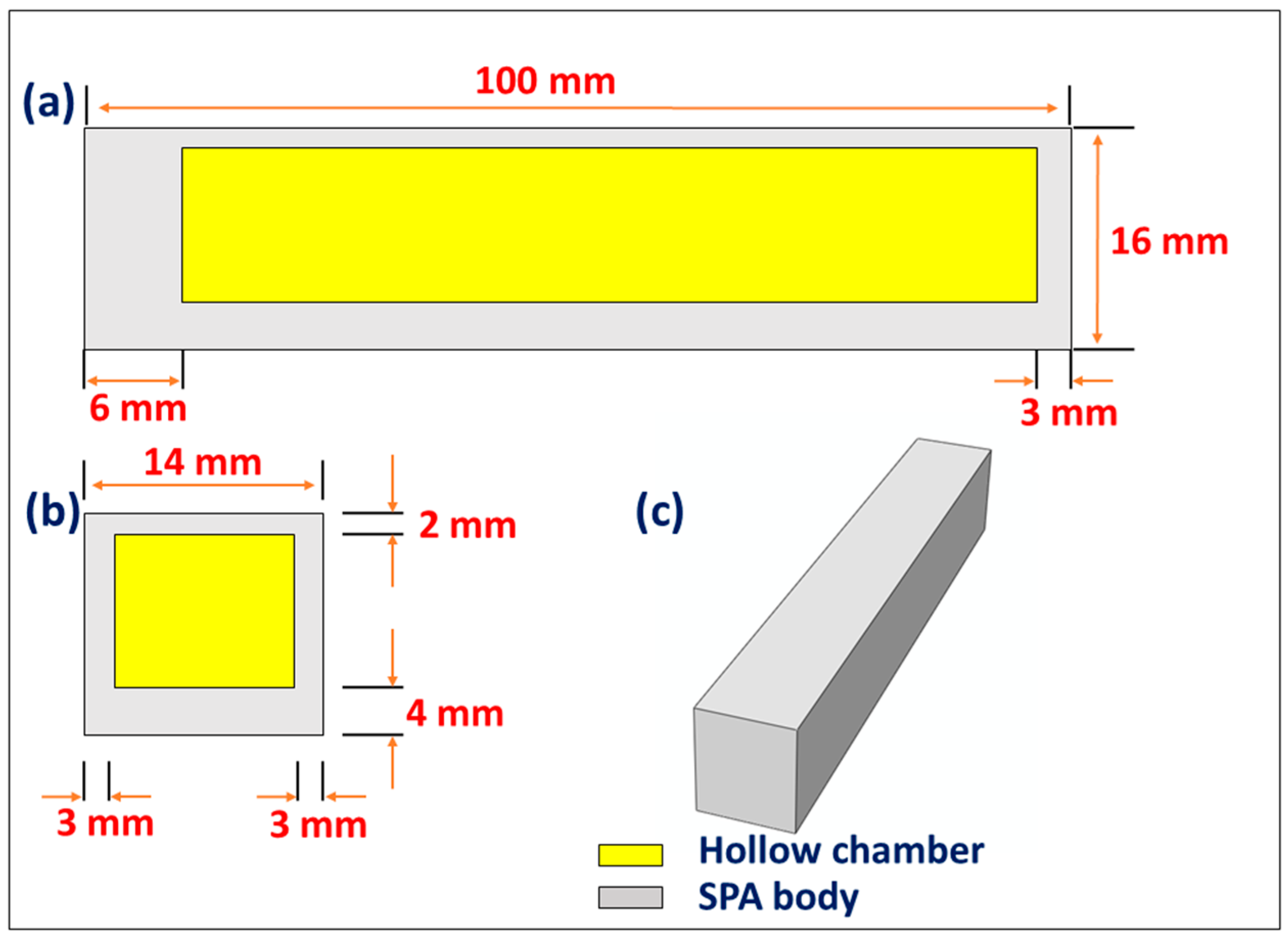

2.1. Structural Design

2.2. Finite Element Analysis

2.3. Analytical Modeling

2.4. Data-Driven Modeling

3. Results

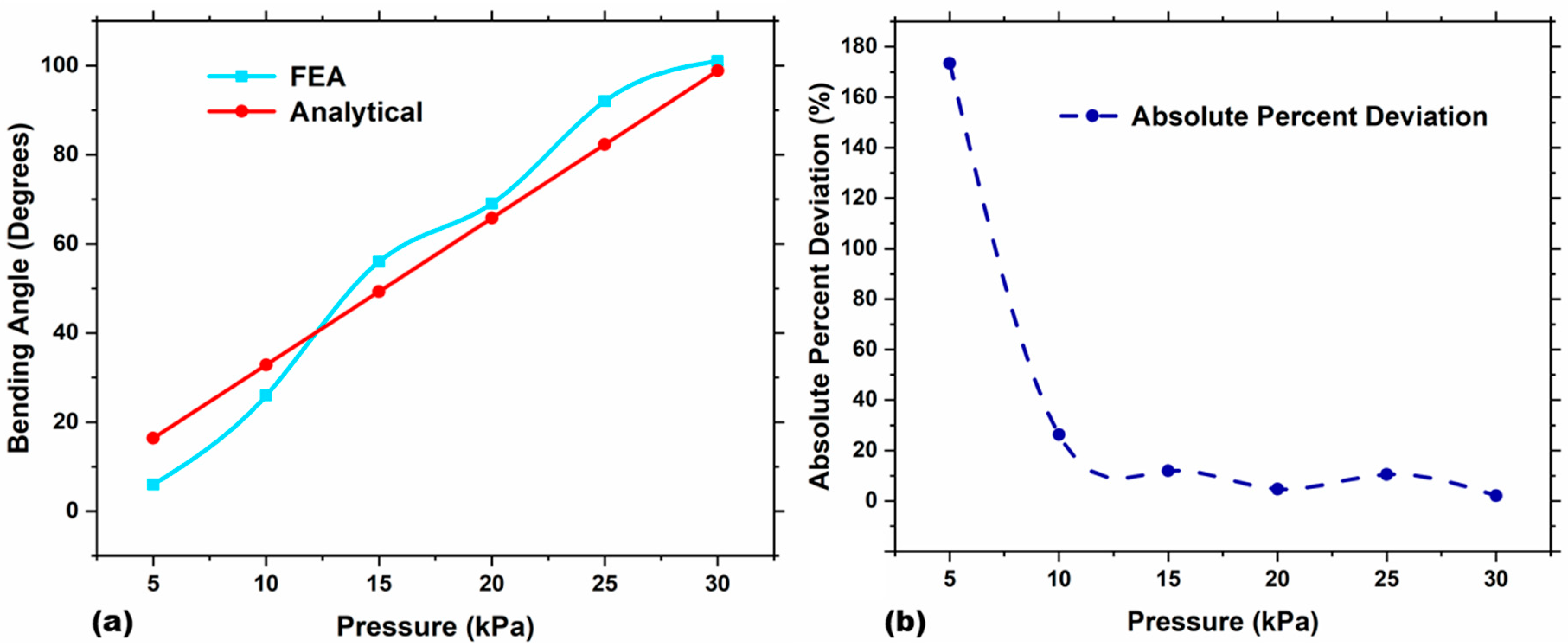

3.1. Finite Element Analysis (FEA)

3.2. Analytical Modeling

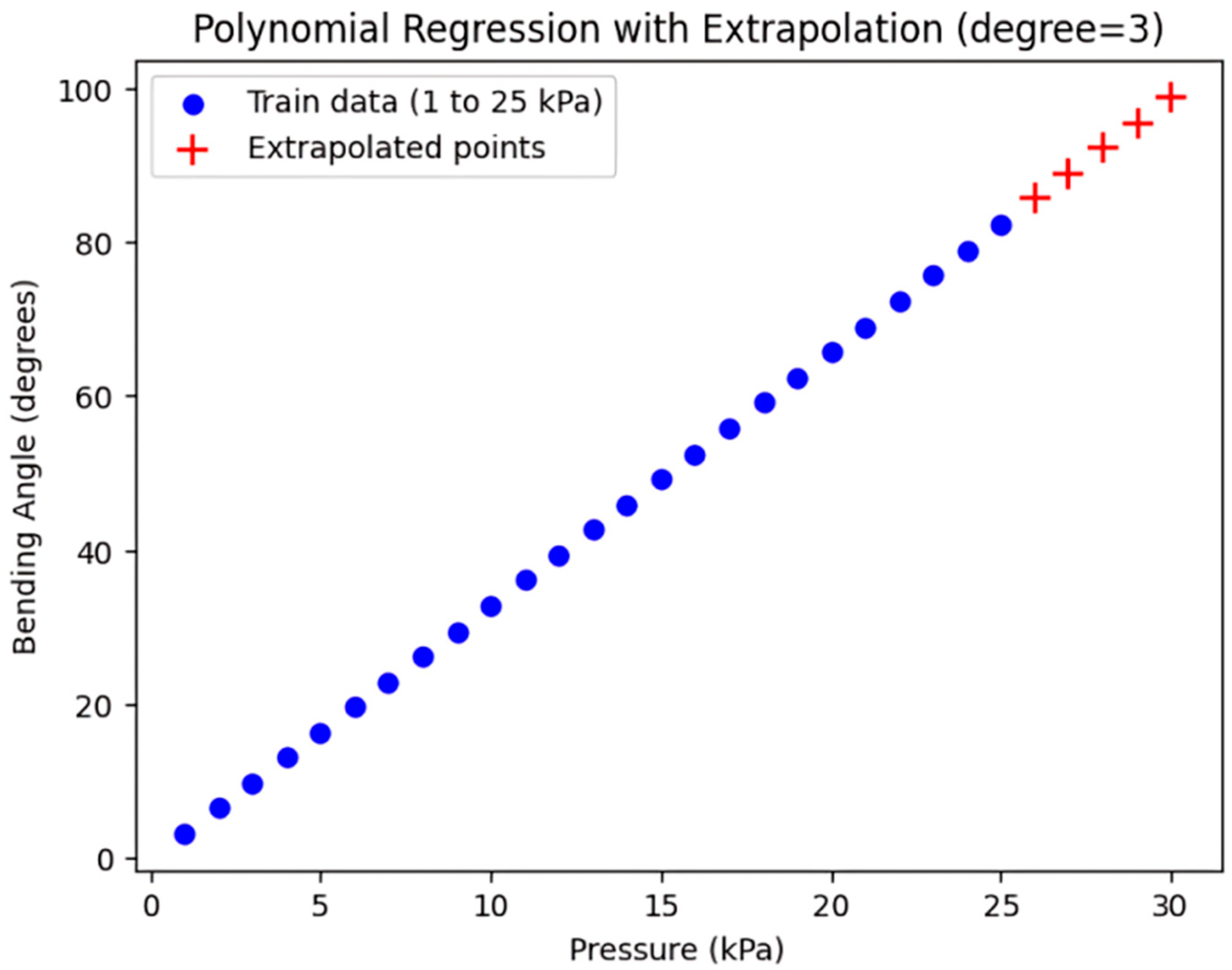

3.3. Data Driven Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albu-Schaffer, A.; Eiberger, O.; Grebenstein, M.; Haddadin, S.; Ott, C.; Wimbock, T.; Hirzinger, G. Soft robotics. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2008, 15, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, M.S.; Tawk, C.D.; Zolfagharian, A.; Pinskier, J.; Howard, D.; Young, T.; Fleming, A.J. Soft pneumatic actuators: A review of design, fabrication, modeling, sensing, control and applications. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 59442–59485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasa, O.; Toshimitsu, Y.; Michelis, M.Y.; Jones, L.S.; Filippi, M.; Buchner, T.; Katzschmann, R.K. An overview of soft robotics. Annu. Rev. Control Robot. Auton. Syst. 2023, 6, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, C.; Su, J.; Tan, J.M.R.; He, K.; Chen, X.; Magdassi, S. Sensing in soft robotics. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 15277–15307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steck, D.; Qu, J.; Kordmahale, S.B.; Tscharnuter, D.; Muliana, A.; Kameoka, J. Mechanical responses of Ecoflex silicone rubber: Compressible and incompressible behaviors. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 47025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Yang, J.; Hossain, M.; Chagnon, G.; Jing, L.; Yao, X. On the stress recovery behaviour of Ecoflex silicone rubbers. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2021, 206, 106624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Yuan, C.; Liang, X.; Dong, T.; Liu, T.; Zhang, J.; Bowen, C. Soft actuators and robotic devices for rehabilitation and assistance. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2022, 4, 2100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NGariya; Kumar, P.; Prasad, B. Stress and bending analysis of a soft pneumatic actuator considering different hyperelastic materials. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 65, 3126–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrentino, P.; Tabrizian, S.K.; Brancart, J.; Van Assche, G.; Vanderborght, B.; Terryn, S. FEA-based inverse kinematic control: Hyperelastic material characterization of self-healing soft robots. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2021, 29, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, M.S.; Fleming, A.J.; Yong, Y.K. Finite element modeling of soft fluidic actuators: Overview and recent developments. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2021, 3, 2000187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Wang, T.; Zhu, S. Simplified dynamical model and experimental verification of an underwater hydraulic soft robotic arm. Smart Mater. Struct. 2022, 31, 075011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alici, G.; Canty, T.; Mutlu, R.; Hu, W.; Sencadas, V. Modeling and experimental evaluation of bending behavior of soft pneumatic actuators made of discrete actuation chambers. Soft Robot. 2018, 5, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Weng, D.; Li, Z.; Chen, L.; Ma, Y.; Wang, J. Deformation analysis for magnetic soft continuum robots based on minimum potential energy principle. Smart Mater. Struct. 2024, 33, 115040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, G.; Dou, W.; Zhang, X.; Yi, H. Bending analysis and contact force modeling of soft pneumatic actuators with pleated structures. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2021, 193, 106150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Calderon, A.D.; Huang, X.; Wu, G.; Liang, C. Design and Driving Performance Study of Soft Actuators for Hand Rehabilitation Training. Med. Devices 2024, 17, 237–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Sakhaei, A.H.; Shafiee, M. Machine learning-based constitutive modelling for material non-linearity: A review. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, H.; Sharma, A. 4D-Printed Soft Pneumatic Actuators Guided by Machine Learning and Finite Element Models. J. Manuf. Eng. 2024, 19, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolfagharian, A.; Durran, L.; Gharaie, S.; Rolfe, B.; Kaynak, A.; Bodaghi, M. 4D printing soft robots guided by machine learning and finite element models. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2021, 328, 112774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaber, S.; Liu, Z.; Sun, Y. Physics-guided deep learning enabled surrogate modeling for pneumatic soft robots. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 11441–11448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Scharff, R.B.; Long, S.; Han, C.; Du, D. Modelling of soft fiber-reinforced bending actuators through transfer learning from a machine learning algorithm trained from FEM data. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2024, 368, 115095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoras, C.C.; Zichil, V.; Ciubotariu, V.A.; Cosa, S.M. Machine learning, mechatronics, and stretch forming: A history of innovation in manufacturing engineering. Machines 2024, 12, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Su, H. A High Performance Pneumatically Actuated Soft Gripper Based on Layer Jamming. ASME J. Mech. Robotics. Febr. 2023, 15, 014501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gariya, N.; Kumar, P.; Prasad, B. Development of a Soft Pneumatic Actuator with In-built Flexible Sensing Element for Soft Robotic Applications. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2023, 109, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavazza, J.; Contino, M.; Marano, C. Strain rate, temperature and deformation state effect on Ecoflex 00-50 silicone mechanical behaviour. Mech. Mater. 2023, 178, 104560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Chen, Y.; Guo, X.; Du, C.; Zhang, D.; Li, J. Two ANCF Hyperelastic Reduced Beam Elements based on Neo-Hookean and Yeoh Models. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.; Qamar, S.Z.; Pervez, T.; Khan, R.; Al-Kharusi, M.S.M. Elastomer seals in cold expansion of petroleum tubulars: Comparison of material models. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2012, 27, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.; Goes, F.D.; Kim, T. Stable neo-hookean flesh simulation. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2018, 37, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud, C.; Cros, J.M.; Feng, Z.Q.; Yang, B. The Yeoh model applied to the modeling of large deformation contact/impact problems. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2009, 36, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Steinmann, P. Extension of the Arruda—Boyce model to the modelling of the curing process of polymers. PAMM 2011, 11, 389–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anssari-Benam, A.; Destrade, M.; Saccomandi, G. Modelling brain tissue elasticity with the Ogden model and an alternative family of constitutive models. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2022, 380, 20210325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauchau, O.A.; Craig, J.I. Euler-Bernoulli beam theory. In Structural Analysis; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 173–221. [Google Scholar]

- Civalek, Ö.; Demir, Ç. Bending analysis of microtubules using nonlocal Euler–Bernoulli beam theory. Appl. Math. Model. 2011, 35, 2053–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elishakoff, I.; Kaplunov, J.; Nolde, E. Celebrating the centenary of Timoshenko’s study of effects of shear deformation and rotary inertia. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2015, 67, 060802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, F.; Polygerinos, P.; Walsh, C.J.; Bertoldi, K. Mechanical programming of soft actuators by varying fiber angle. Soft Robot. 2015, 2, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lin, X.; Liu, J.; Lu, N. Shear-lag model of laminated films with alternating stiff and soft layers wrinkling on soft substrates. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2025, 202, 106172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, G.; Tawk, C.D.; Zolfagharian, A.; Pinskier, J.; Howard, D.; Young, T. Timoshenko-Beam-Based Modeling of Soft Pneumatic Actuators. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 4027–4034. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, D.B.; Abdel-Malek, K. Characterization of the Poisson’s ratio of soft materials. Exp. Mech. 2021, 61, 1167–1177. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Christov, I.C. Reduced models of unidirectional flows in compliant rectangular ducts at finite Reynolds number. Phys. Fluids 2021, 33, 102004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morala, P.; Cifuentes, J.A.; Lillo, R.E.; Ucar, I. Towards a mathematical framework to inform neural network modelling via polynomial regression. Neural Netw. 2021, 142, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.; Hu, W.; Li, M.; Zhang, J.; Song, X.; Sun, W. Ensemble regression based on polynomial regression-based decision tree and its application in the in-situ data of tunnel boring machine. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 188, 110022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S. No. | Pressure (kPa) | Bending Angle (Degrees) | Absolute Percentage Deviation (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical | ML Model | |||

| 1 | 26 | 85.61 | 85.607 | 0.004 |

| 2 | 27 | 88.91 | 88.913 | 0.003 |

| 3 | 28 | 92.22 | 92.221 | 0.001 |

| 4 | 29 | 95.53 | 95.529 | 0.001 |

| 5 | 30 | 98.84 | 98.839 | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aryan, N.; Gariya, N.; Sankhwar, P. Integrating Physics-Based and Data-Driven Approaches for Accurate Bending Prediction in Soft Pneumatic Actuators. Designs 2025, 9, 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs9060137

Aryan N, Gariya N, Sankhwar P. Integrating Physics-Based and Data-Driven Approaches for Accurate Bending Prediction in Soft Pneumatic Actuators. Designs. 2025; 9(6):137. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs9060137

Chicago/Turabian StyleAryan, Nikhil, Narendra Gariya, and Pravin Sankhwar. 2025. "Integrating Physics-Based and Data-Driven Approaches for Accurate Bending Prediction in Soft Pneumatic Actuators" Designs 9, no. 6: 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs9060137

APA StyleAryan, N., Gariya, N., & Sankhwar, P. (2025). Integrating Physics-Based and Data-Driven Approaches for Accurate Bending Prediction in Soft Pneumatic Actuators. Designs, 9(6), 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs9060137