Solar-Thermal Process Intensification for Blue Hydrogen Production: Integrated Steam Methane Reforming with a Waste-Derived Red Mud Catalyst

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

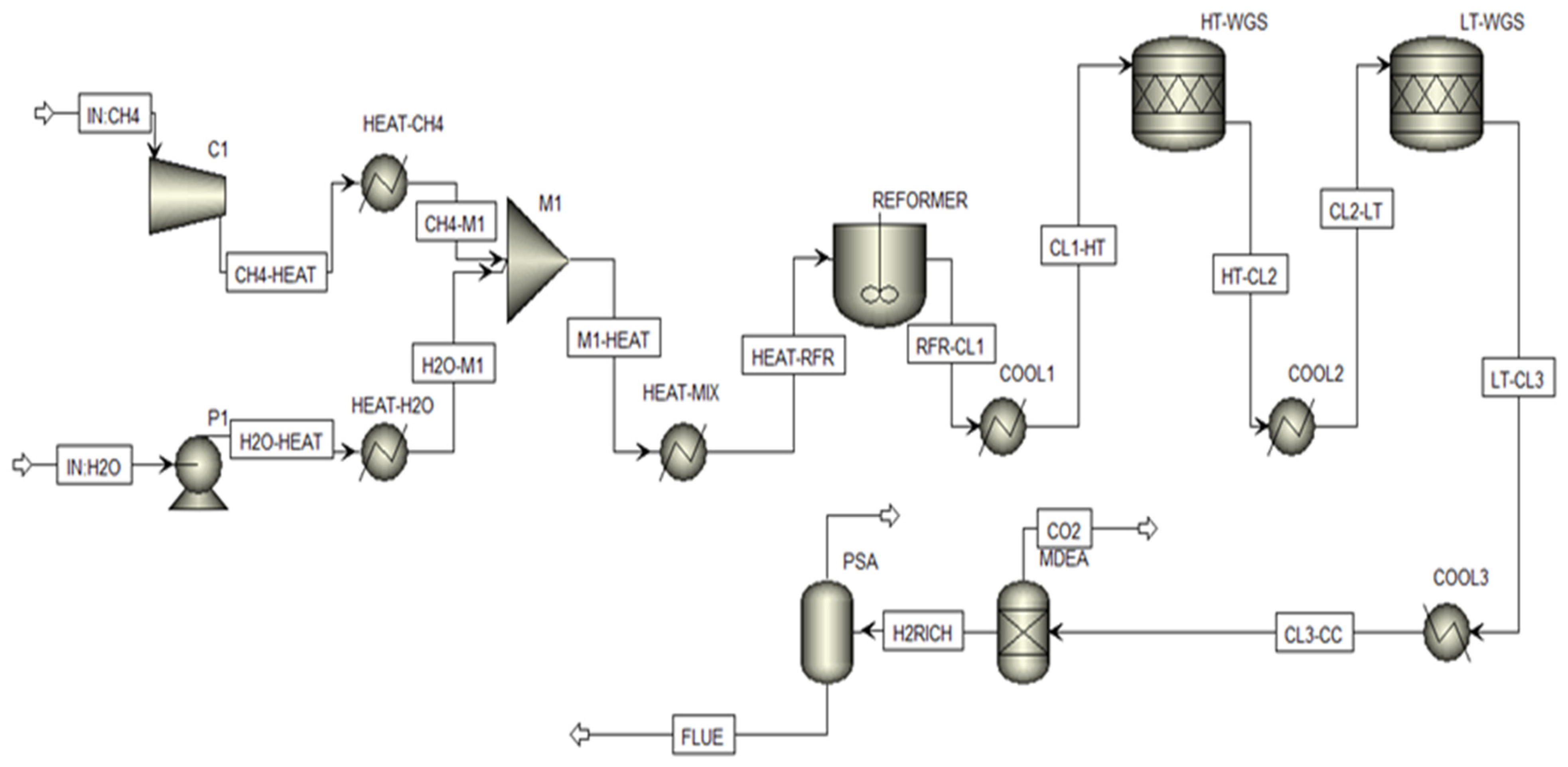

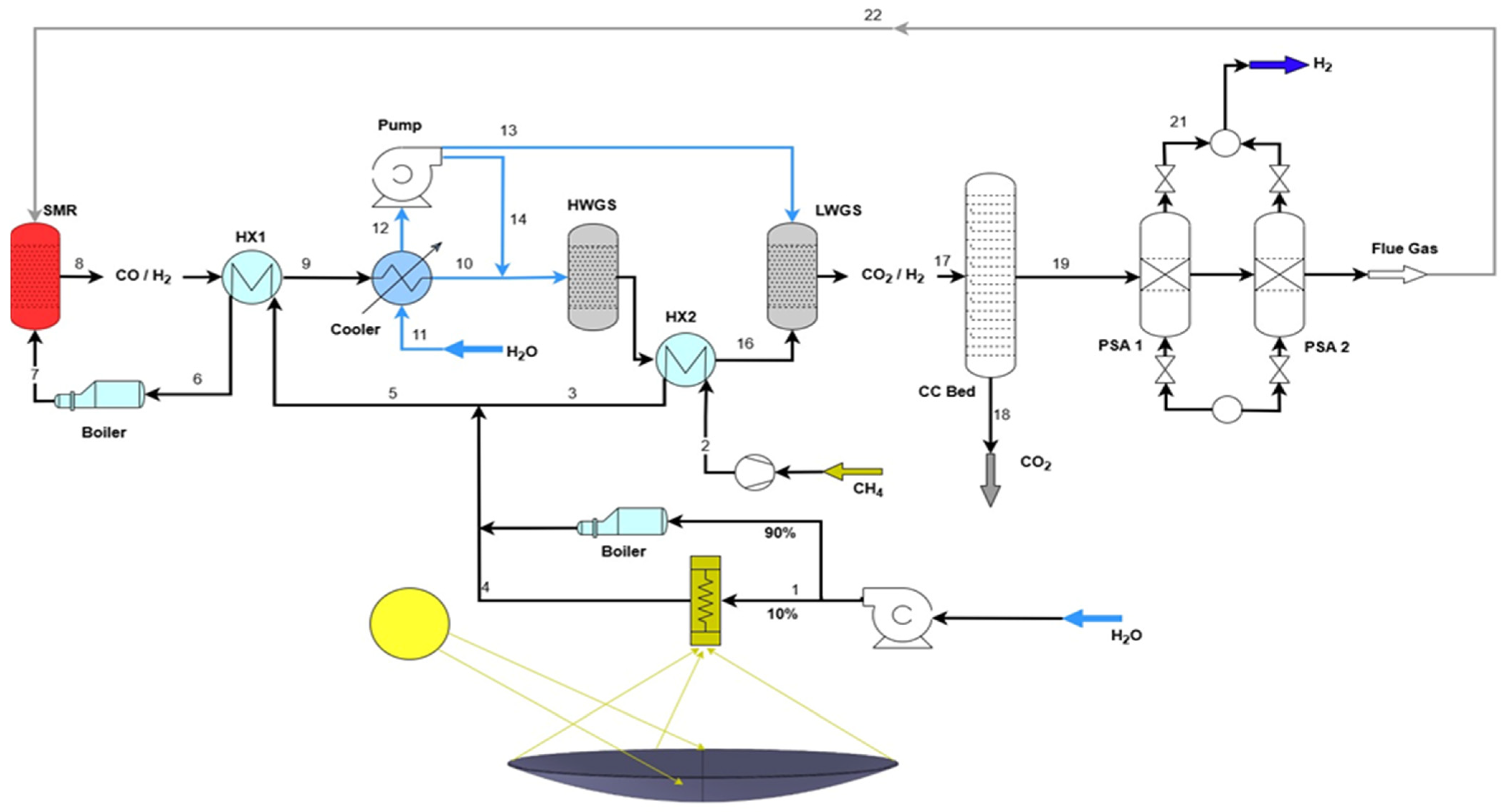

2.1. Overall Process Design and Simulation

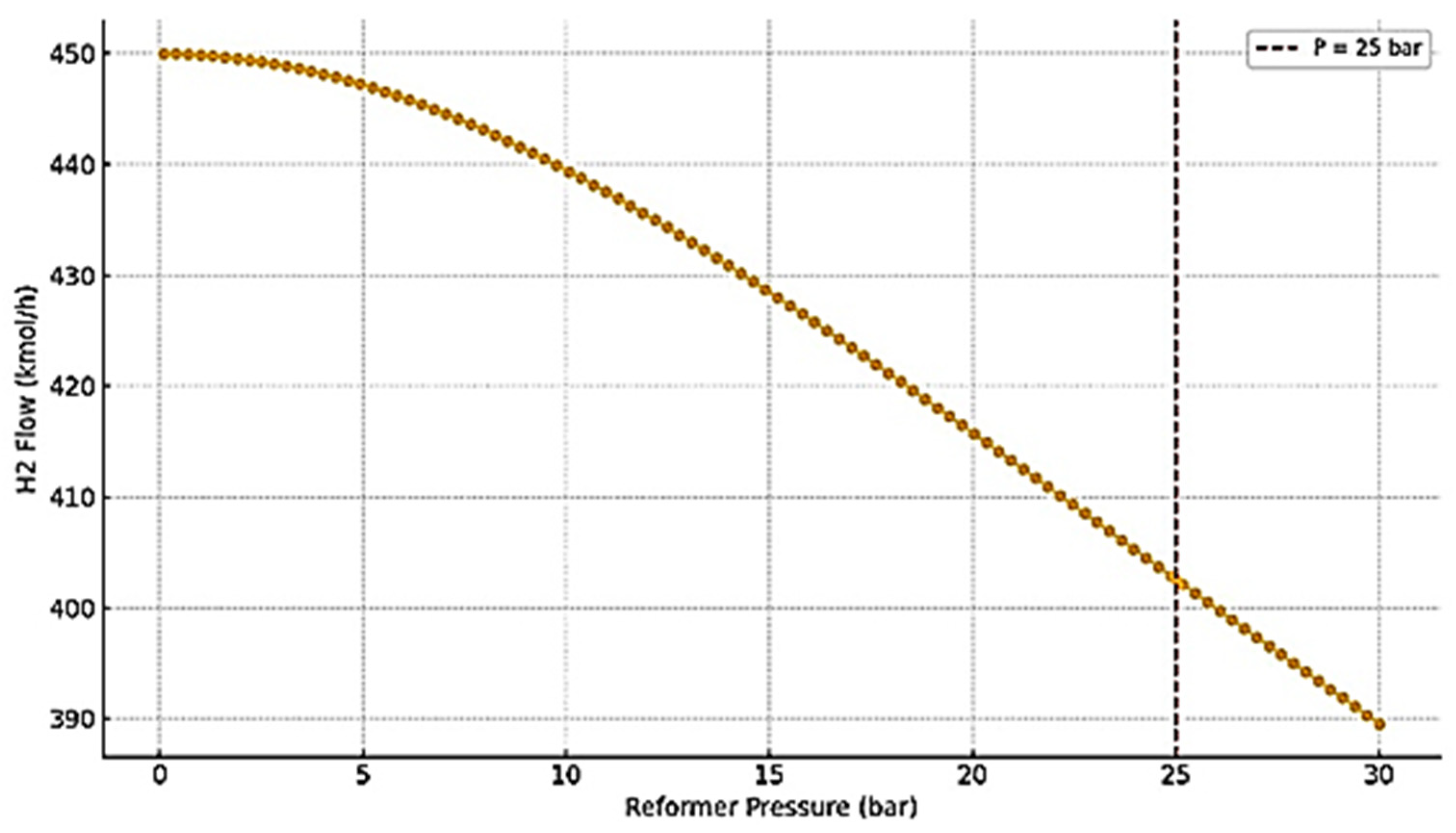

- Feedstock Preparation: Natural gas (modeled as pure methane) and water were compressed to the system pressure of 25 bar.

- Solar-Thermal Heating: Water was preheated and vaporized. A portion of this duty (10%) was supplied by a solar parabolic dish (SPD), modeled externally in COMSOL Multiphysics version 6.2 (Section 2.2). The SPD raised the steam temperature to 477 °C. The remaining 90% of the heat was supplied by a conventional natural gas-fired boiler. Methane was preheated separately to 500 °C using a boiler.

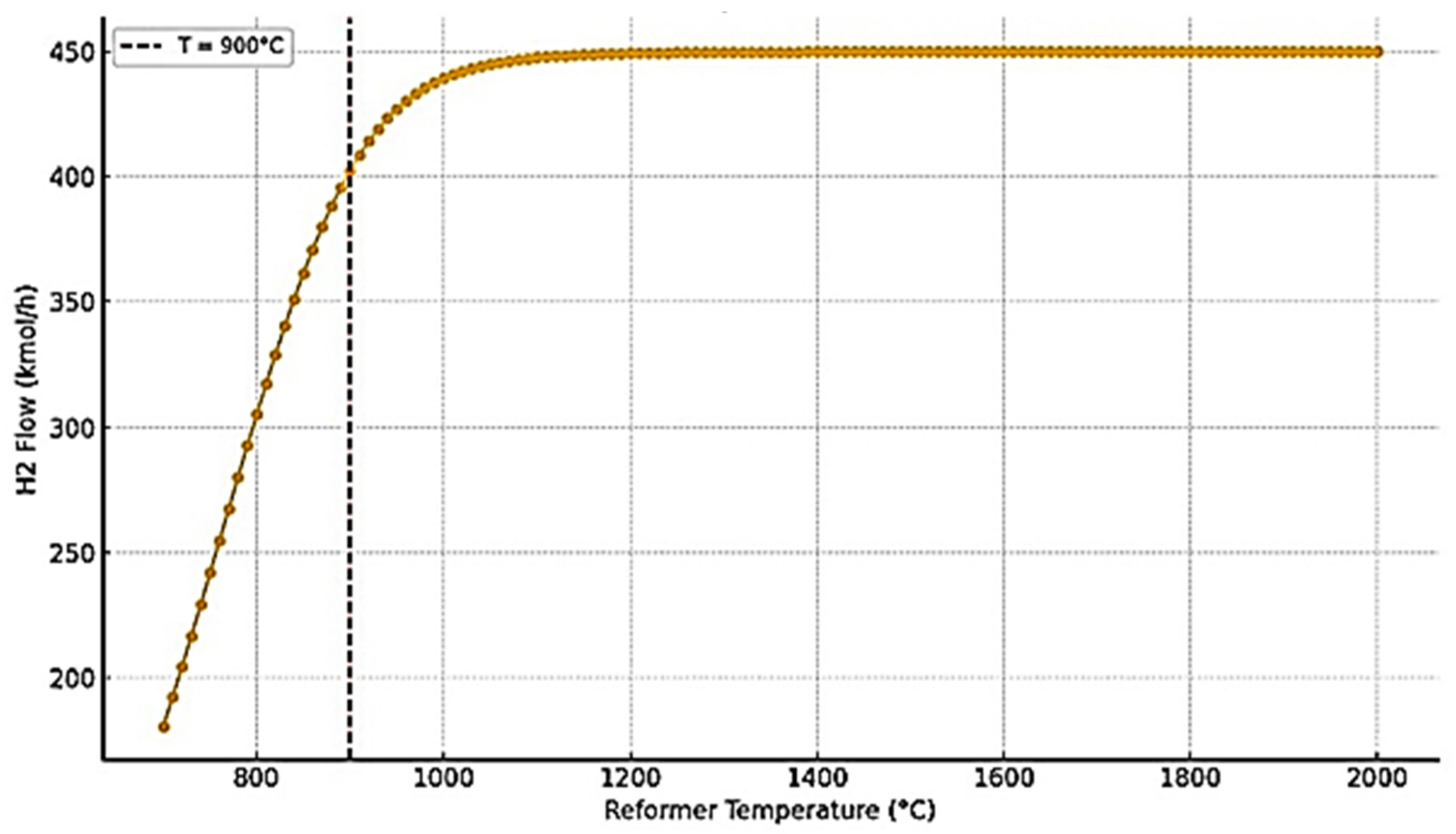

- Reforming Section: The preheated methane and steam (S/C = 3) were mixed and further heated to 900 °C before entering an equilibrium-based SMR reactor (RGibbs model in ASPEN Plus). This model was selected to reflect the assumption of fast kinetics and thermodynamic equilibrium at the optimized high-temperature conditions [4].

- Water-Gas Shift (WGS): The syngas effluent was cooled and passed through high-temperature (450 °C) and low-temperature (250 °C) shift reactors. These were modeled as stoichiometric reactors (RStoic) with a fixed CO conversion of 85% per stage, representing near-equilibrium operation as commonly applied in industrial design [17].

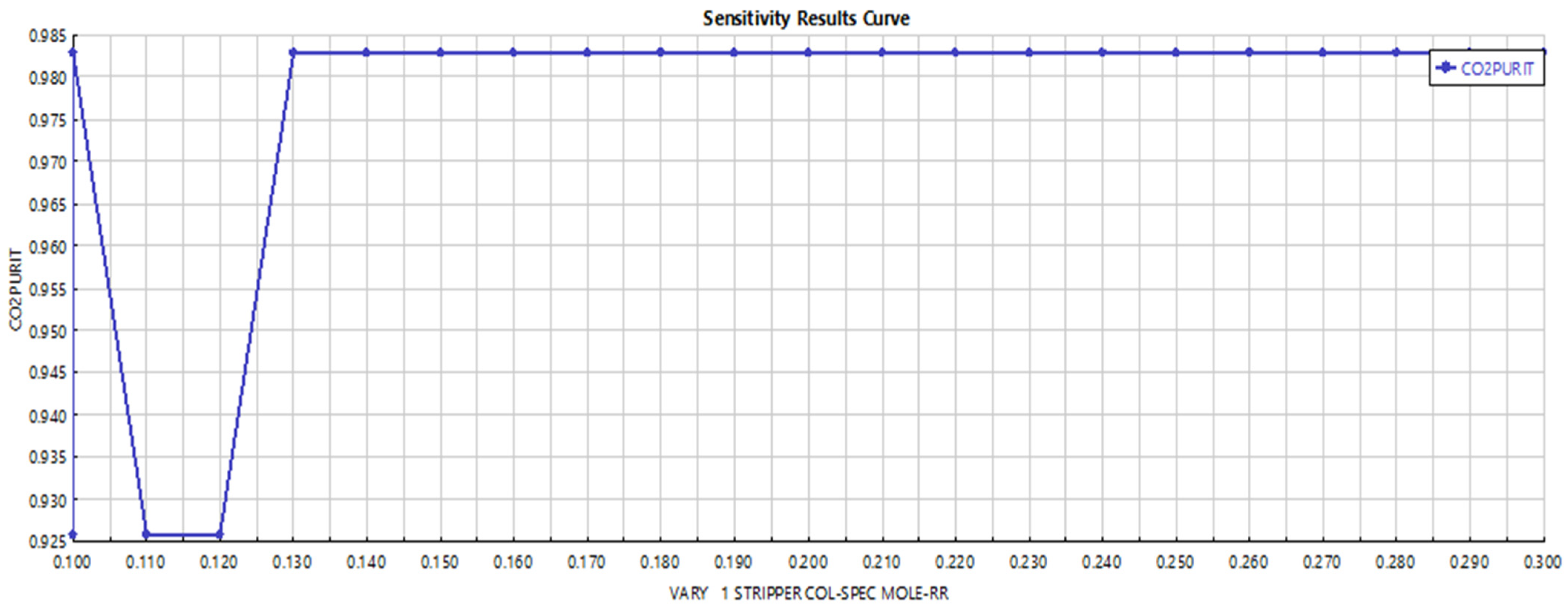

- Carbon Capture: The CO2-rich stream was treated in an amine-based absorption column using a 50 wt.% methyl diethanol amine (MDEA) solution. The column was designed to achieve a CO2 capture efficiency of 95%, with the captured CO2 stream achieving 97% purity after regeneration in a distillation column and flash drum [18].

- Hydrogen Purification: The decarbonized syngas was finally purified using a Pressure Swing Adsorption (PSA) unit, modeled in Advanced System for Process Engineering Adsorption software manufactured by Aspen Technology, Inc (US), ASPEN Adsorption version 10. A standard 4-bed, 12-step cycle was configured to produce hydrogen with a purity of 99.99% [19]. The PSA off-gas, rich in CH4 and CO, was recycled to the reformer furnace as fuel.

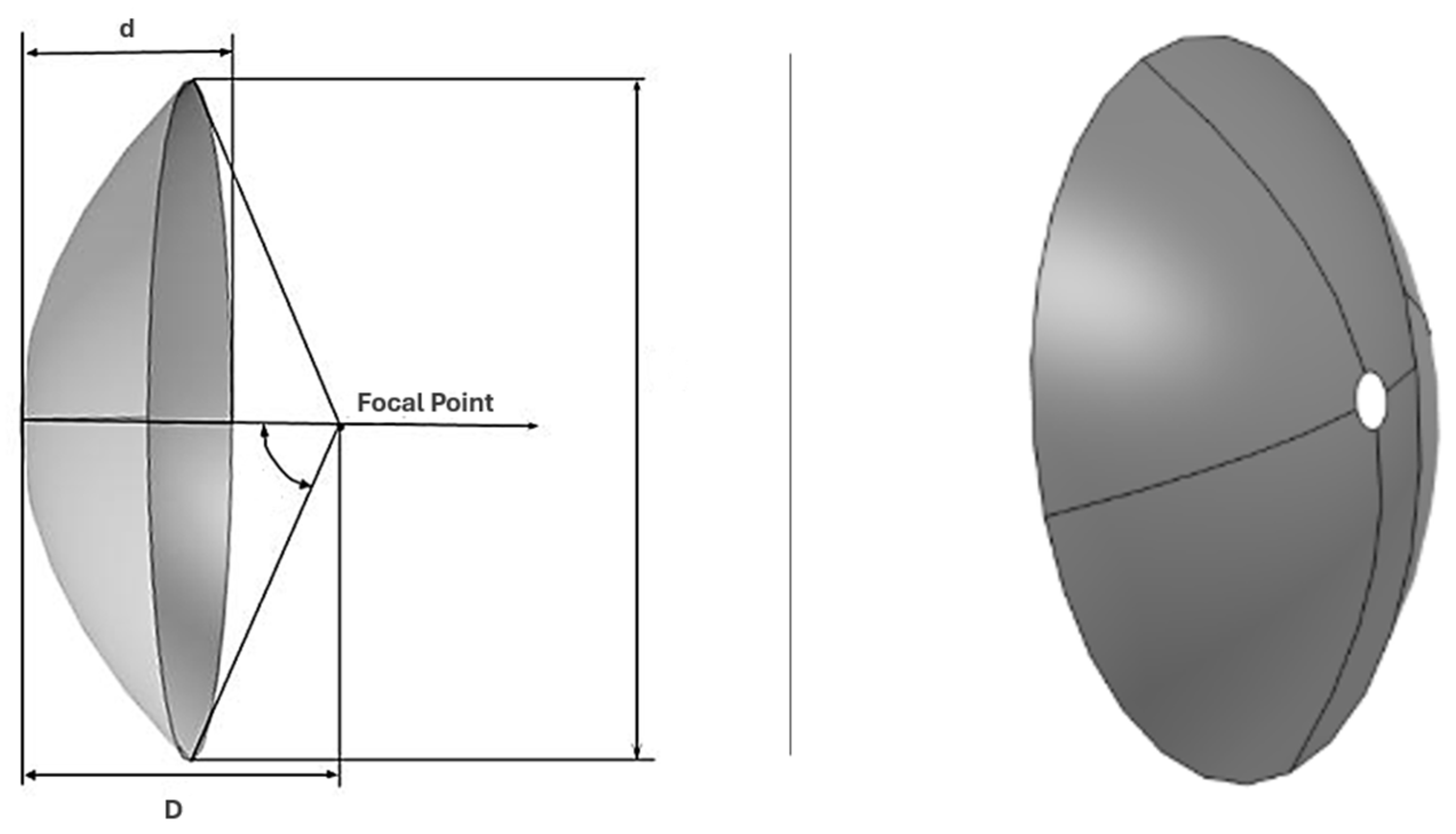

2.2. Solar Parabolic Dish (SPD) Modeling

2.2.1. Numerical Model Setup and Validation

Mesh Resolution and Independence

Boundary Conditions and Convergence Criteria

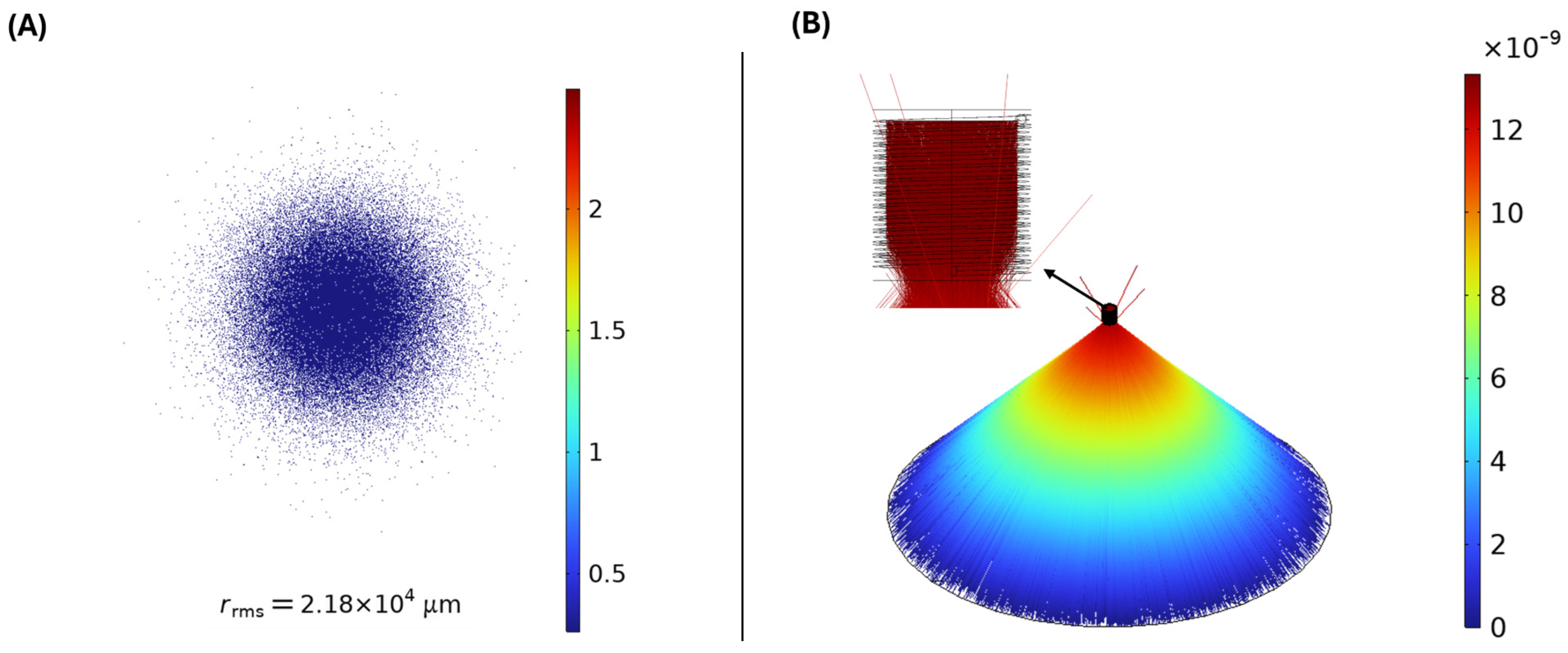

Ray Trajectory and Ray Spot Diagram

Temperature Distribution and Energy Balance

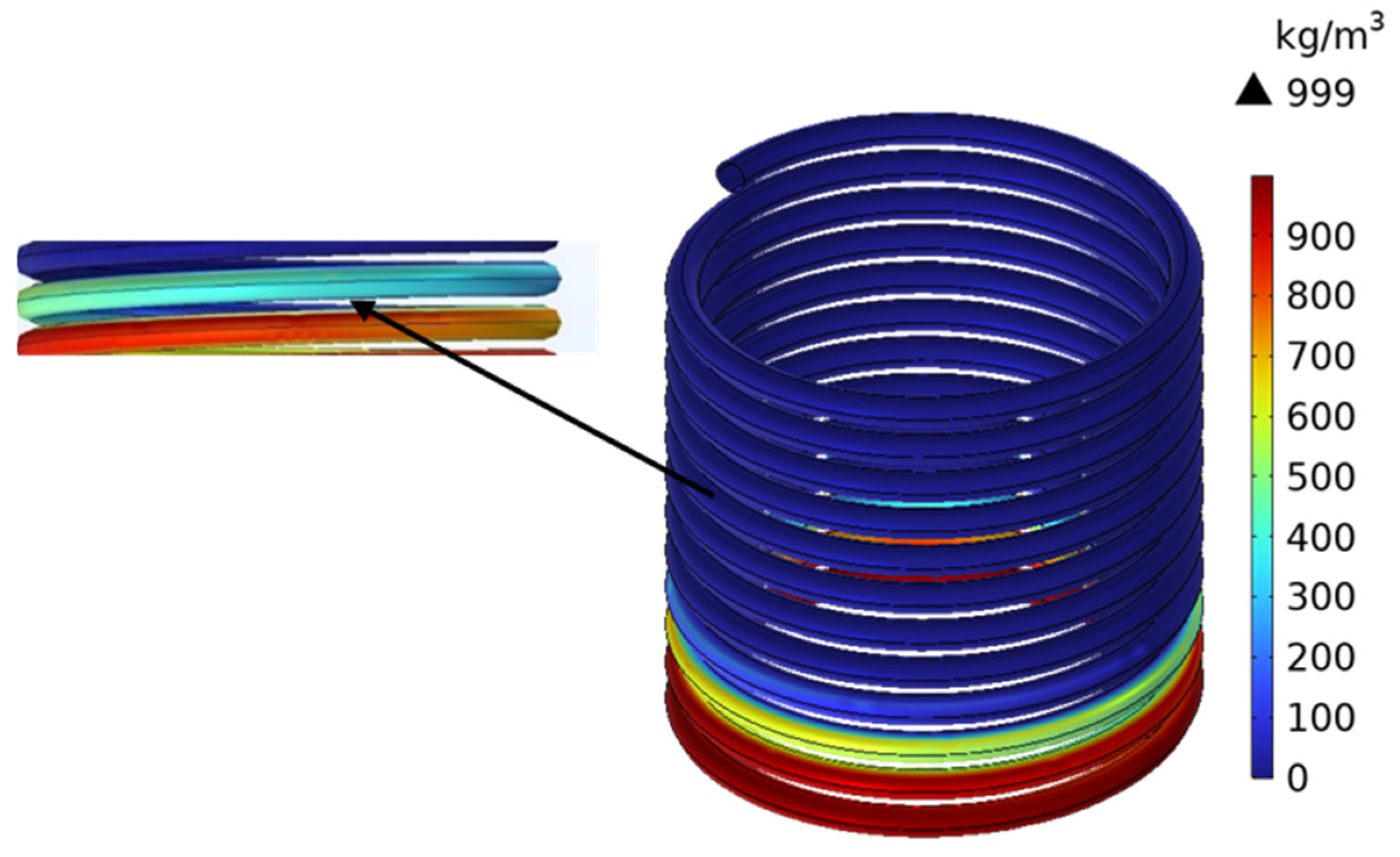

Fluid Thermodynamic Profile and Vapor Quality

2.3. Receiver Mechanical Design and Safety Validation

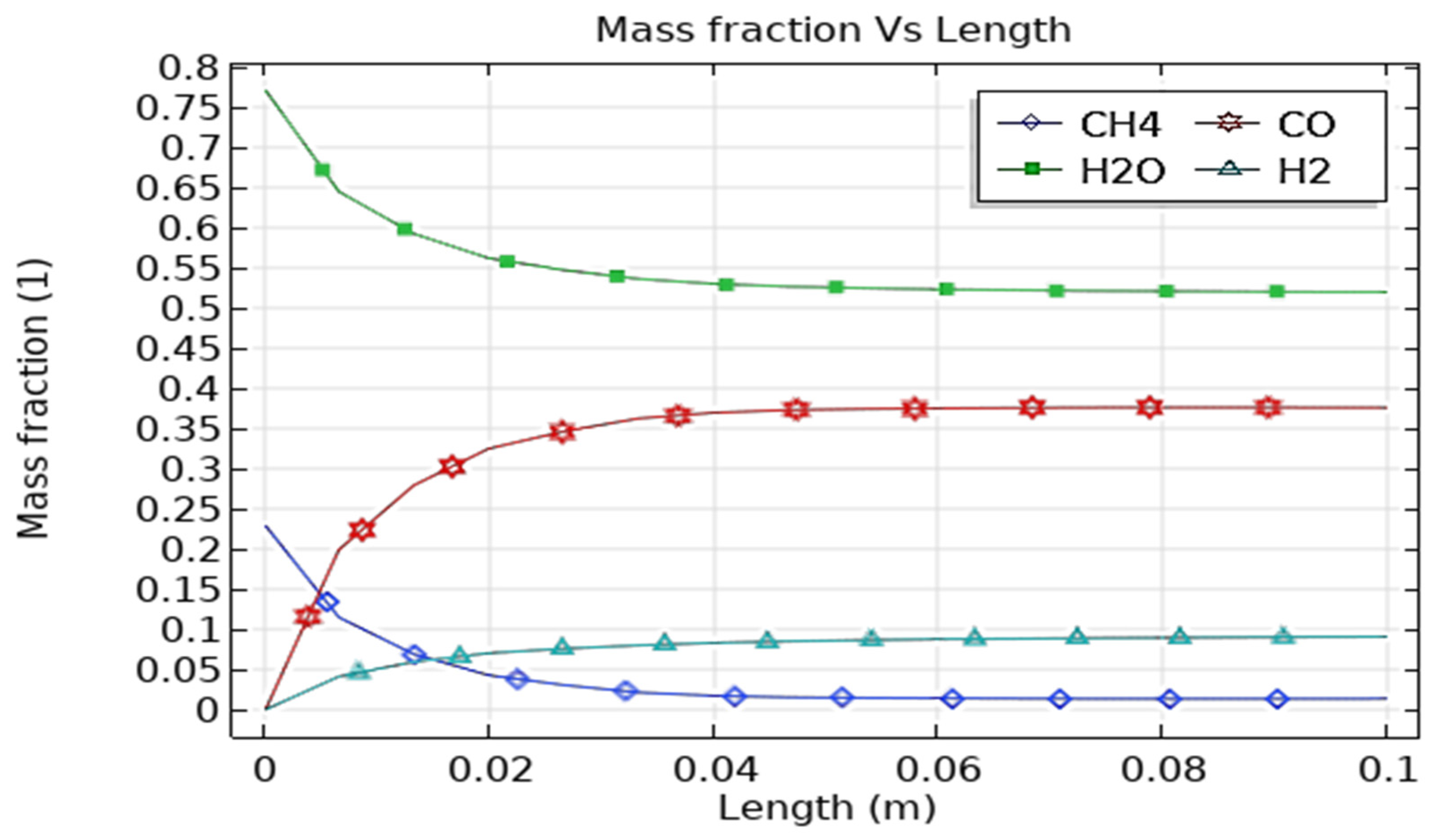

2.4. Steam Methane Reactor Modeling

2.5. Pressure Swing Adsorption and Carbon Capture-Based MDEA-Based Modeling

2.6. Methodology of Simulation and Coupled Physics

2.7. Red Mud Catalyst Preparation and Characterization

- Drying: Raw red mud was dried at 105 °C for 12 h to remove moisture.

- Grinding: The dried material was ground and sieved to a particle size of <100 μm.

- Calcination: The powder was heated in a muffle furnace at 600 °C for 4 h in air to stabilize the metal oxide phases and potentially mitigate the deactivating effects of alkali components.

- Composite Formation: The activated red mud was physically mixed with commercially available ZSM-5 zeolite (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA.) in a 1:1 weight ratio. The mixture was extruded, dried, and finally calcined at 550 °C for 2 h to enhance mechanical stability and surface properties.

2.8. Techno-Economic Analysis (TEA)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Solar Thermal System Performance

3.2. SMR Reactor Optimization and Performance

3.3. Hydrogen Purification and Carbon Capture

3.4. Techno-Economic Assessment

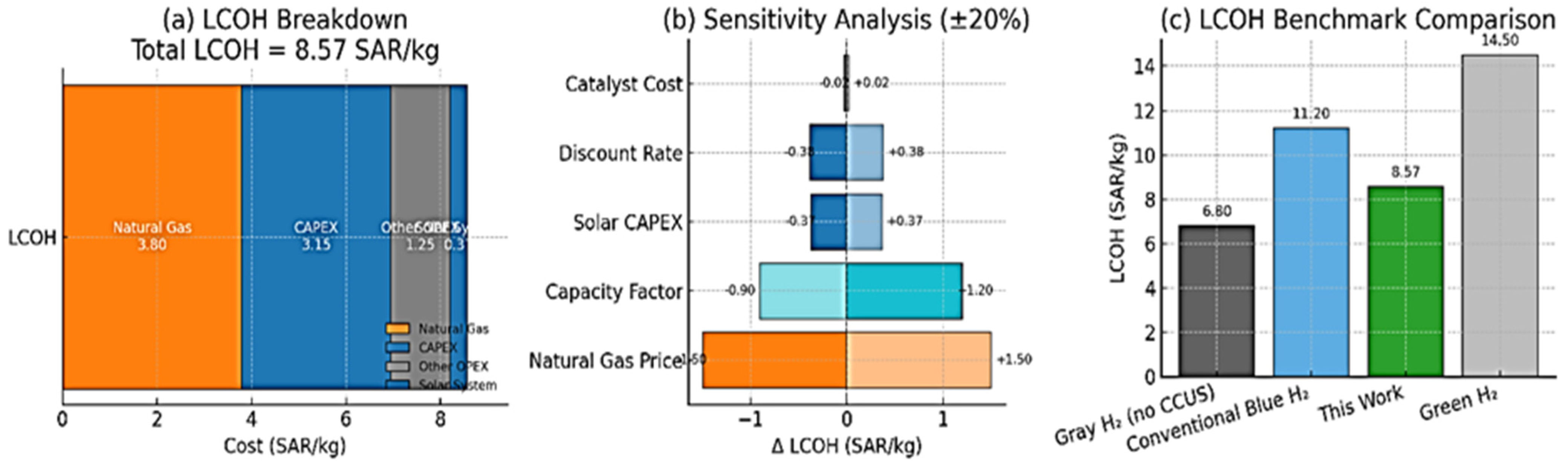

- Catalyst Cost: The prepared red mud-zeolite composite catalyst was calculated to have a cost of 3.89 SAR/g (1.04 USD/g) (Table 4), which is over 75% lower than the market price of a conventional Ni-based catalyst ~17.25 SAR/g (4.60 USD/g). This drastic reduction in a major consumable cost significantly improves operating economics.

- Solar Integration Benefits: The integration of the SPD system demonstrates the technical feasibility of supplying high-temperature renewable heat to industrial processes. While involving a capital investment, the system directly offsets natural gas consumption, resulting in calculated annual fuel savings of approximately 9500 SAR (2530 USD) and corresponding CO2 emission reductions. The calculated annual fuel savings of approximately 9500 SAR are based on a conservative estimate that accounts for real-world solar field performance, including an average DNI during operation lower than the design-point value, expected maintenance downtime, and boiler efficiency at the point of fuel displacement. The primary value of solar integration in this configuration is the demonstrated pathway for decarbonizing high-temperature industrial heat rather than direct economic savings.

- Levelized Cost of Hydrogen (LCOH): The overall LCOH for the integrated plant, accounting for all capital and operational expenditures, was calculated to be 8.57 SAR/kg (2.29 USD/kg) (Table 2). This value is highly competitive with reported costs for both conventional blue hydrogen and renewable green hydrogen in the region [28,29], demonstrating the economic promise of the proposed intensified process.

3.4.1. Prospective Analysis for Increased Solar Contribution

Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) Breakdown

4. Conclusions

- Effective Solar Integration: A solar parabolic dish (SPD) system was proven capable of effectively supplying a significant portion (10%) of the high-temperature heat required for SMR. The system generated superheated steam at 477 °C with a receiver thermal efficiency of 52.4%, directly reducing fossil fuel consumption and associated emissions.

- Successful Waste Valorization: Red mud, a problematic and abundant industrial waste, was successfully processed and activated to function as an effective, low-cost catalyst for SMR. The catalyst cost of 3.89 SAR/g represents a reduction of over 75% compared to conventional Ni-based catalysts, drastically improving operating economics.

- High Process Performance: The fully integrated system was optimized to produce high-purity (99.99%) hydrogen at a rate of 1070 kg/h while simultaneously capturing 95% of the produced CO2 at 97% purity, fully meeting the stringent criteria for blue hydrogen production.

- Strong Economic Competitiveness: The techno-economic analysis confirmed the viability of this approach, yielding a highly competitive levelized cost of hydrogen (LCOH) of 8.57 SAR/kg. The synergies between solar heat integration (reducing OPEX) and waste-derived catalyst use (slashing a major consumable cost) are the key drivers of this economic advantage.

- The solar thermal integration provides a viable pathway for reducing the carbon footprint of conventional SMR processes, demonstrating the technical feasibility of renewable heat integration in high-temperature industrial applications. While the direct economic savings are modest (~9500 SAR/year), the environmental value of displacing fossil-derived process heat represents a significant benefit for low-carbon hydrogen production.

Future Work Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SMR | Steam Methane Reforming |

| SPD | Solar Parabolic Dish |

| PSA | Pressure Swing Adsorption |

| WGS | Water-Gas Shift |

| MDEA | Methyl Diethanol Amine |

| LCOH | Levelized Cost of Hydrogen |

| DNI | Direct Normal Irradiance |

| S/C | Steam-to-Carbon ratio |

| CCUS | Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage |

| CSP | Concentrated Solar Power |

| EDS | Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

Appendix A. Optical Modeling of the Solar Parabolic Dish (SDP)

Appendix B. Thermo-Fluid Modeling of the Receiver

Appendix C. Chemical Kinetics and Reactor Modeling for Steam Methane Reforming (SMR)

Appendix D. Pressure Swing Adsorption Modeling (PSA)

Appendix E. Carbon Capture Unit Modeling (MDEA Modeling)

References

- Kopeinig, H. Renewable Energy Generation and Consumption in the Aggregate Sector. Master’s Thesis, Technical University of Leoben, Leoben, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Alami, A.H.; Olabi, A.G.; Mdallal, A.; Rezk, A.; Radwan, A.; Rahman, S.M.A.; Shah, S.K.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Concentrating Solar Power (CSP) Technologies: Status and Analysis. Int. J. Thermofluids 2023, 18, 100340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shboul, B.; Khawaldeh, H.A.; Al-Smairan, M.; Alrbai, M.; Ali, H.H.; Almomani, F. Perspectives of new solar energy option for sustainable residential electricity generation: A comparative techno-economic evaluation of photovoltaic and solar dish systems. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 4514–4527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlović, S.R.; Vasiljević, D.M.; Stefanović, V.P.; Stamenković, Z.M.; Bellos, E.A. Optical Analysis and Performance Evaluation of a Solar Parabolic Dish Concentrator. Therm. Sci. 2016, 20, 1237–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amayreh, M.I.; Alahmer, A.; Manasrah, A. A Novel Parabolic Solar Dish Design for a Hybrid Solar Lighting-Thermal Applications. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 1136–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.A.-Z.; Shaikh, P.H.; Zhang, S.; Lashari, A.A.; Leghari, Z.H.; Baloch, M.H.; Memon, Z.A.; Caiming, C. A Review on Design Parameters and Specifications of Parabolic Solar Dish Stirling Systems and Their Applications. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 4128–4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, A.A.; El-Marghany, M.R.; El-Awady, W.M.; Hamed, A.M. Recent Advances in Parabolic Dish Solar Concentrators: Receiver Design, Heat Loss Reduction, and Nanofluid Optimization for Enhanced Efficiency and Applications. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2024, 273, 112930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korawan, A.D. Karakteristik penyimpan kalor laten pada parabolic mirror dish. J. Penelit. Dan Pengabdi. Kpd. Masy. UNSIQ 2023, 10, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bellos, E.; Bousi, E.; Tzivanidis, C.; Pavlovic, S. Optical and Thermal Analysis of Different Cavity Receiver Designs for Solar Dish Concentrators. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2019, 2, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhalaf, Q.; Lee, D.; Kumar, R.; Thapa, S.; Singh, A.R.; Akhtar, M.N.; Asif, M.; Ağbulut, Ü. Experimental Investigation of the Thermal Efficiency of a New Cavity Receiver Design for Concentrator Solar Technology. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 53, 103848. [Google Scholar]

- Arjun Singh, K.; Natarajan, S.K. Thermal Analysis of Modified Conical Cavity Receiver for a Paraboloidal Dish Collector System. Energy Sources Part A Recov. Util. Environ. Effects 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malviya, R.; Baredar, P.V.; Kumar, A. Thermal Performance Improvement of Solar Parabolic Dish System Using Modified Spiral Coil Tubular Receiver. Int. J. Photoenergy 2021, 2021, 4517923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Shuai, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, B. Effects of Material Selection on the Thermal Stresses of Tube Receiver under Concentrated Solar Irradiation. Mater. Des. 2012, 33, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigalotti, L.D.G.; Alvarado-Rodríguez, C.E.; Rendón, O. Fluid Flow in Helically Coiled Pipes. Fluids 2023, 8, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Zeid, M.A.-R.; Elhenawy, Y.; Toderaș, M.; Bassyouni, M.; Majozi, T.; Al-Qabandi, O.A.; Kishk, S.S. Performance Enhancement of Solar Still Unit Using V-Corrugated Basin, Internal Reflecting Mirror, Flat-Plate Solar Collector and Nanofluids. Sustainability 2024, 16, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, H.G.; Diabil, H.A.N.; Al-Fahham, M.A. Performance Study on a Solar Concentrator System for Water Distillation Using Different Water Nanofluids. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avargani, V.M.; Zendehboudi, S. Parametric Analysis of a High-Temperature Solar-Driven Propane Steam Reformer for Hydrogen Production in a Porous Bed Catalytic Reactor. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 276, 116539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, S.; Sápi, A.; Khoja, A.H.; Najari, S.; Ayesha, M.; Kónya, Z.; Asare-Bediako, B.B.; Tatarczuk, A.; Hessel, V.; Keil, F.J. Evolution Paths from Gray to Turquoise Hydrogen via Catalytic Steam Methane Reforming: Current Challenges and Future Developments. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 183, 113392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.M.; Abbas, S.Z.; Maqbool, F.; Ramirez-Solis, S.; Dupont, V.; Mahmud, T. Modeling of Sorption Enhanced Steam Methane Reforming in an Adiabatic Packed Bed Reactor Using Various CO2 Sorbents. J. Envrion. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105863. [Google Scholar]

- Alfuhaid, L.T.; Nasser, G.A.; Alabdulhadi, R.A.; Khan, M.Y.; Yamani, Z.H.; Helal, A. Steam Reforming of Dodecane Using Ni-Red Mud Catalyst: A Sustainable Approach for Hydrogen Production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 86, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Shen, J.; Niu, Y.; Yang, J.F.; Wei, X. Synergistic CO2 Mineralization Using Coal Fly Ash and Red Mud as a Composite System. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2024, 11, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Aswath, M.U.; Das Biswas, R.; Ranganath, R.V.; Choudhary, H.K.; Kumar, R.; Sahoo, B. Role of Iron in the Enhanced Reactivity of Pulverized Red Mud: Analysis by Mössbauer Spectroscopy and FTIR Spectroscopy. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2019, 11, e00266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucsi, G.; Halyag, N.; Kurusta, T.; Kristály, F. Control of Carbon Dioxide Sequestration by Mechanical Activation of Red Mud. Waste Biomass Valorization 2021, 12, 6481–6495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento, T.M.; Gambarra, F.G.d.S.; Rodrigues, M.G.F. Valorization of Bauxite Residue for Use as Adsorbent for Reactive Blue Removal: Regeneration Evaluation. Processes 2025, 13, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Shuai, B.; Zhang, X.; Hu, X.; Zhang, H.; Jia, Y.; Yang, Z.; Guan, X. Polyurethane/Red Mud Composites with Flexibility, Stretchability, and Flame Retardancy for Grouting. Polymers 2018, 10, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babatabar, M.A.; Saidi, M. Hydrogen Production via Integrated Configuration of Steam Gasification Process of Biomass and Water--gas Shift Reaction: Process Simulation and Optimization. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 19378–19394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerman, J.C.; Hamborg, E.S.; Van Keulen, T.; Ramírez, A.; Turkenburg, W.C.; Faaij, A.P.C. Techno-Economic Assessment of CO2 Capture at Steam Methane Reforming Facilities Using Commercially Available Technology. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2012, 9, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oni, A.O.; Anaya, K.; Giwa, T.; Di Lullo, G.; Kumar, A. Comparative Assessment of Blue Hydrogen from Steam Methane Reforming, Autothermal Reforming, and Natural Gas Decomposition Technologies for Natural Gas-Producing Regions. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 254, 115245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antzara, A.; Heracleous, E.; Bukur, D.B.; Lemonidou, A.A. Thermodynamic Analysis of Hydrogen Production via Chemical Looping Steam Methane Reforming Coupled with in Situ CO2 Capture. Energy Procedia 2014, 63, 6576–6589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Section | Reactor Type | T (°C) | P (bar) | Key Parameter | Rationale/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMR | RGibbs | 900 | 25 | S/C = 3, Equilibrium | Fast kinetics, high T [4] |

| HT-WGS | RStoic | 450 | 25 | 85% CO Conversion | Near-equilibrium [17] |

| LT-WGS | RStoic | 250 | 25 | 85% CO Conversion | Near-equilibrium [17] |

| MDEA Absorber | RadFrac | 40 | 24 | 95% Capture Efficiency | Standard design [18] |

| PSA Unit | Custom | 40 | 24-1 | 4-bed, 12-step cycle | H2 purity > 99.99% [19] |

| Symbol/Item | Value | Unit | Description/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geometrical Parameters | |||

| Dish Focal Length (F) | 3 | m | |

| Dish Diameter (D) | 5 | m | |

| Dish Projected Area (A) | 19.635 | m2 | |

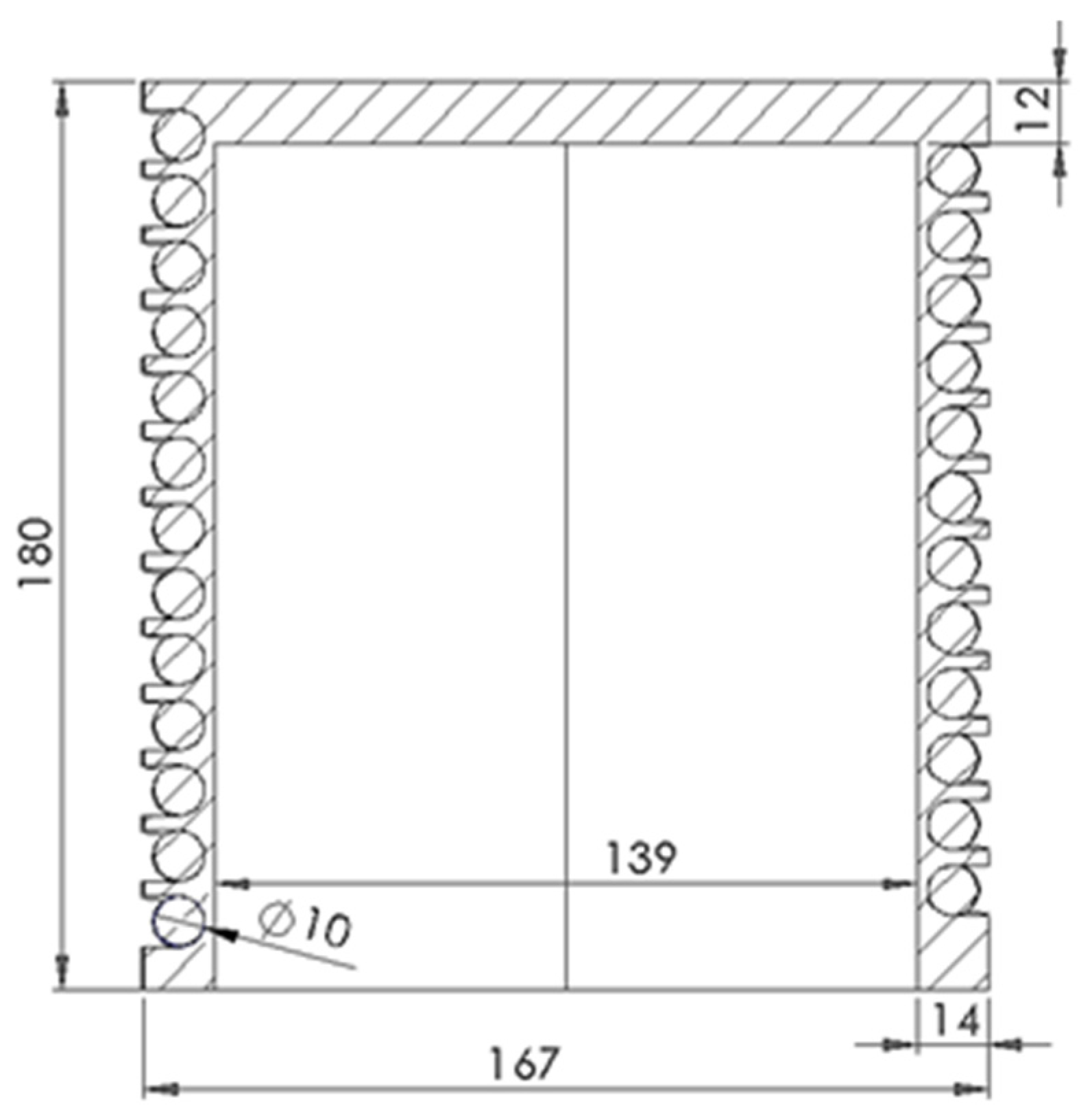

| Receiver Cavity Radius (Rc) | 139 | mm | |

| Tube Outer Radius (R) | 5.0 | mm | |

| Tube Outer Diameter (Do) | 10.0 | mm | |

| Tube Wall Thickness (t) | 1.20 | mm | Conservative for pressure and corrosion |

| Tube Inner Diameter (Di) | 7.60 | mm | |

| Helix Radius (Rh) | 124 | mm | Allows for manufacturing clearance |

| Curvature Ratio (γ) | 0.0327 | - | |

| Axial Pitch (p) | 16.2 | mm | |

| Total Tube Length (Ltotal) | 6.24 | m | For (N = 8) turns |

| Symbol/Item | Value | Unit | Description/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operational and Material Limits | |||

| Design Pressure (P) | 30 | bar | |

| Max Tube Wall Temp (Tmax) | 495 | °C | From CFD (Figure 7B) |

| Thin-Wall Hoop Stress () | 12.5 | MPa | () |

| Inconel 600 Yield Strength (at 495 °C) | ≈250 | MPa | Conservative, temp-dependent value |

| Safety Factors and Margins | |||

| Safety Factor (Pressure) | ≈20 | - | |

| Manufacturability | Suitable | - | Mandrel bending; (Rh ≫ 3Do) |

| Parameter | Value | Source/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Plant Lifetime | 25 years | Standard assumption |

| Annual Operating Hours | 7884 h | (90% availability) |

| Discount Rate | 8% | |

| Natural Gas Price | 5.85 SAR/GJ (1.56 USD/GJ) | Local market data |

| Electricity Tariff | 0.18 SAR/kWh (0.048 USD/kWh) | Local market data |

| Ni-based Catalyst Cost | 17.25 SAR/g (4.60 USD/g) | Market quote [RiOGen Inc., Winston-Salem, NC, USA] |

| Red Mud-Zeolite Catalyst | 3.89 SAR/g | Calculated (This work) |

| Solar Dish Cost | 31 × 85,000 SAR/unit (31 × 22,667 USD) | Vendor quote and literature estimate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maatallah, T.; Al-Zahrani, M.; Hilal, S.; Alsubaie, A.; Aljohani, M.; Alghamdi, M.; Almansour, F.; Awad, L.; Slimani, Y.; Ali, S. Solar-Thermal Process Intensification for Blue Hydrogen Production: Integrated Steam Methane Reforming with a Waste-Derived Red Mud Catalyst. Designs 2025, 9, 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs9060138

Maatallah T, Al-Zahrani M, Hilal S, Alsubaie A, Aljohani M, Alghamdi M, Almansour F, Awad L, Slimani Y, Ali S. Solar-Thermal Process Intensification for Blue Hydrogen Production: Integrated Steam Methane Reforming with a Waste-Derived Red Mud Catalyst. Designs. 2025; 9(6):138. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs9060138

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaatallah, Taher, Mussad Al-Zahrani, Salman Hilal, Abdullah Alsubaie, Mohammad Aljohani, Murad Alghamdi, Faisal Almansour, Loay Awad, Yassine Slimani, and Sajid Ali. 2025. "Solar-Thermal Process Intensification for Blue Hydrogen Production: Integrated Steam Methane Reforming with a Waste-Derived Red Mud Catalyst" Designs 9, no. 6: 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs9060138

APA StyleMaatallah, T., Al-Zahrani, M., Hilal, S., Alsubaie, A., Aljohani, M., Alghamdi, M., Almansour, F., Awad, L., Slimani, Y., & Ali, S. (2025). Solar-Thermal Process Intensification for Blue Hydrogen Production: Integrated Steam Methane Reforming with a Waste-Derived Red Mud Catalyst. Designs, 9(6), 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs9060138