Evaluating the Clinical Validity of Commercially Available Virtual Reality Headsets for Visual Field Testing: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

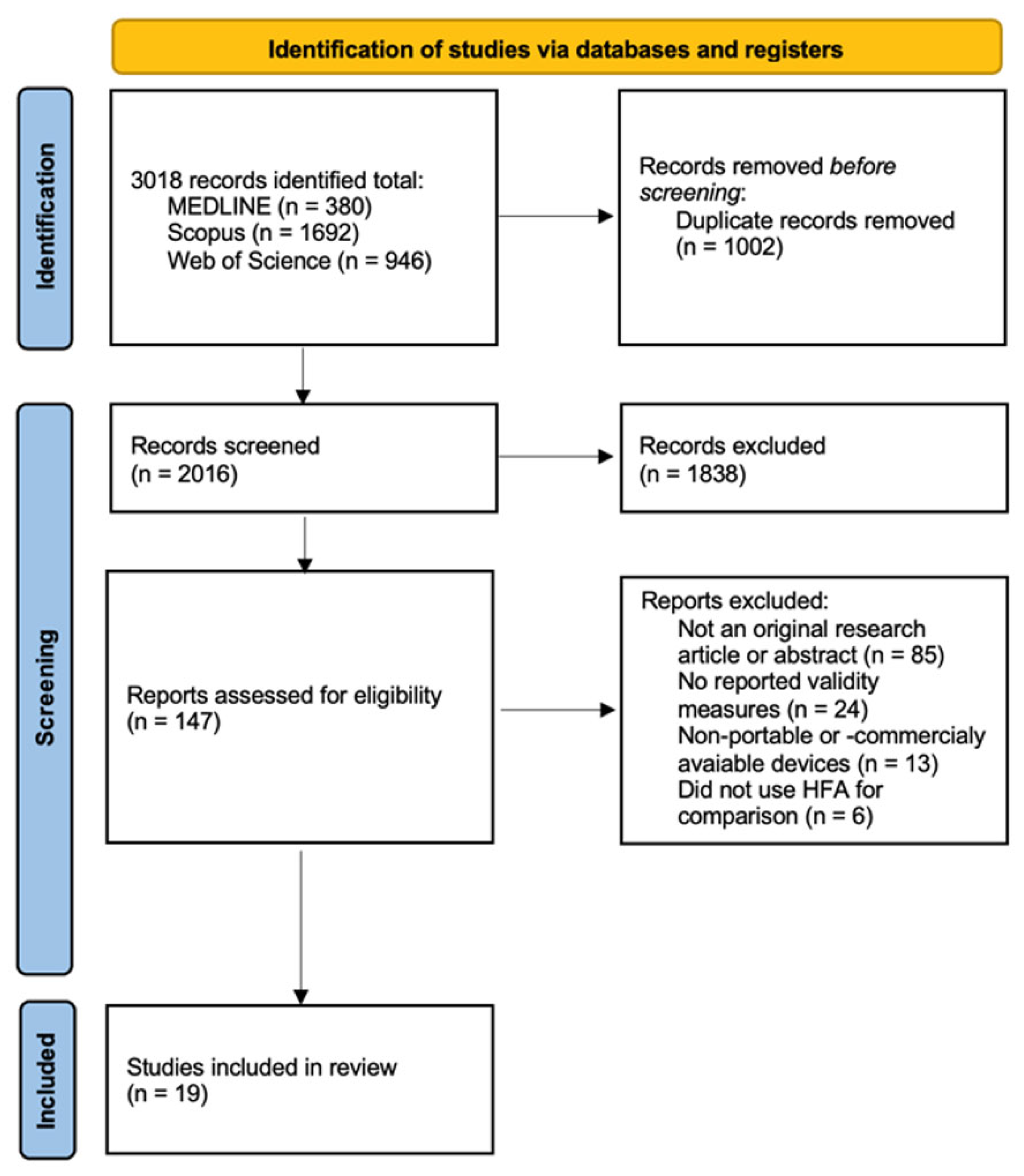

2.2. Study Selection

- Participants: individuals with and without visual field defects.

- Intervention: visual field assessment using commercially available VR-based perimetry devices and standard perimetry (HFA).

- Comparison: the Humphrey Field Analyzer using the Swedish Interactive Thresholding Algorithm (24-2) SITA-Standard protocol (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc., Dublin, CA, USA).

- Outcome: measures of validity comparing VR-based perimetry results to those obtained using the HFA.

2.3. Data Extraction

- Study characteristics: authors, year of publication, journal, and setting (clinical or laboratory).

- Participant characteristics: clinical condition (e.g., glaucoma, healthy control, neuro-ophthalmic diseases), number of participants, number of eyes evaluated, average age (including range when available), and diagnostic classification.

- VR perimetry device characteristics: type of technology (e.g., smartphone, tablet, laptop, VR headset, handheld controller), display and input modality, presence of eye or gaze tracking capabilities, compatibility with corrective lenses (e.g., glasses or spectacles), and regulatory or market status (e.g., FDA approval, CE mark).

- Testing protocol: thresholding algorithm and stimulus frequency, type of visual field test (e.g., 24-2), test duration (mean and/or range), and monocular vs. binocular presentation.

- Outcomes: key results comparing VR-based perimetry to HFA, including agreement measures (e.g., mean deviation [MD], pattern standard deviation [PSD]) and correlation coefficients.

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.5. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Inclusion and Screening Outcomes

3.2. VR Device Characteristics and Agreement with HFA

4. Discussion

4.1. FDA-Registered Devices

4.2. CE-Marked Devices

4.3. Devices Without FDA or CE Clearance

4.4. Influence of Disease Severity and Population Type

4.5. Technological and Usability Considerations

4.6. Comparative Perspective Across Regulatory Groups

4.7. Methodological Heterogeneity and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Phu, J.; Khuu, S.K.; Yapp, M.; Assaad, N.; Hennessy, M.P.; Kalloniatis, M. The value of visual field testing in the era of advanced imaging: Clinical and psychophysical perspectives. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2017, 100, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Medeiros, F.A. Recent developments in visual field testing for glaucoma. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2018, 29, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, C.A.; Wall, M.; Thompson, H.S. A history of perimetry and visual field testing. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2011, 88, E8–E15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.A.; Kong, G.Y.X.; Liu, C. Visual fields in glaucoma: Where are we now? Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2023, 51, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhar, G.C.; Naduvilath, T.J.; Lakkai, M.; Jayakumar, A.J.; Pandi, G.T.; Mandal, A.K.; Honavar, S.G. Sensitivity of Swedish interactive threshold algorithm compared with standard full threshold algorithm in Humphrey visual field testing. Ophthalmology 2000, 107, 1303–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalicky, S.E.; Kong, G.Y. Novel means of clinical visual function testing among glaucoma patients, including virtual reality. J. Curr. Glaucoma Pract. 2019, 13, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, B.; Heijl, A. False-negative responses in glaucoma perimetry: Indicators of patient performance or test reliability? Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000, 41, 2201–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvan, K.; Mina, M.; Abdelmeguid, H.; Gulsha, M.; Vincent, A.; Sarhan, A. Virtual reality headsets for perimetry testing: A systematic review. Eye 2024, 38, 1041–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prager, A.J.; Kang, J.M.; Tanna, A.P. Advances in perimetry for glaucoma. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2021, 32, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapelfeldt, J.; Kucur, Ş.S.; Huber, N.; Höhn, R.; Sznitman, R. Virtual reality–based and conventional visual field examination comparison in healthy and glaucoma patients. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2021, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.K.I.; Saha, C.; Poon, S.H.L.; Yiu, R.S.W.; Shih, K.C.; Chan, Y.K. Virtual reality and augmented reality—emerging screening and diagnostic techniques in ophthalmology: A systematic review. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2022, 67, 1516–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, C.; Ahmed, I.I.K.; Samuelson, T.W.; Chaglasian, M.; Barnebey, H.; Radcliffe, N.; Bacharach, J. Validation of a Wearable Virtual Reality Perimeter for Glaucoma Staging, The NOVA Trial: Novel Virtual Reality Field Assessment. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobin, J.J.; Walsh, G. Medical Product Regulatory Affairs: Pharmaceuticals, Diagnostics, Medical Devices; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- FDA. Guidance for Industry: Non-Inferiority Clinical Trials to Establish Effectiveness; Citeseer: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Korevaar, D.A.; Cohen, J.F.; de Ronde, M.W.J.; Virgili, G.; Dickersin, K.; Bossuyt, P.M.M. Reporting weaknesses in conference abstracts of diagnostic accuracy studies in ophthalmology. JAMA Ophthalmol 2015, 133, 1464–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sponsel, W.E.; Griffin, J.M.; Slagle, G.T.; Vu, T.A.; Eis, A. Prospective Comparison of VisuALL Virtual Reality Perimetry and Humphrey Automated Perimetry in Glaucoma. J. Curr. Glaucoma Pract. 2024, 18, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phu, J.; Wang, H.; Kalloniatis, M. Comparing a head-mounted virtual reality perimeter and the Humphrey Field Analyzer for visual field testing in healthy and glaucoma patients. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2024, 44, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, S.L.; Linton, E.F.; Brown, E.N.; Makadia, F.; Donahue, S.P. Evaluation of Virtual Reality Perimetry and Standard Automated Perimetry in Normal Children. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2023, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narang, P.; Agarwal, A.; Srinivasan, M.; Agarwal, A. Advanced Vision Analyzer–Virtual Reality Perimeter: Device Validation, Functional Correlation and Comparison with Humphrey Field Analyzer. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2021, 1, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mees, L.; Upadhyaya, S.; Kumar, P.; Kotawala, S.; Haran, S.; Rajasekar, S.; Friedman, D.S.; Venkatesh, R. Validation of a Head-mounted Virtual Reality Visual Field Screening Device. J. Glaucoma 2020, 29, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narang, P.; Rasheed, F.F.; Agarwal, A.M.; Narang, R.M.; Agarwal, A. Comparison of ELISAR-FAST and SITA-FAST strategy for visual field assessment in glaucoma. J. Glaucoma 2024, 34, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narang, P.; Agarwal, A.; Agarwal, A.; Narang, R.; Sundaramoorthy, L. Comparative Analysis of 10-2 Test on Advanced Vision Analyzer and Humphrey Perimeter in Glaucoma. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2023, 3, 100264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odayappan, A.; Sivakumar, P.; Kotawala, S.; Raman, R.; Nachiappan, S.; Pachiyappan, A.; Venkatesh, R. Comparison of a New Head Mount Virtual Reality Perimeter (C3 Field Analyzer) with Automated Field Analyzer in Neuro-Ophthalmic Disorders. J. Neuro-Ophthalmol. 2023, 43, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.; Sayed, A.; McSoley, J.O.; Durbin, M.; Kashem, R.B.; Nicklin, A.O.; Lopez, V.B.; Mijares, G.B.; Chen, M.O.; Shaheen, A.; et al. Comparison of Visual Field Test Measurements With a Novel Approach on a Wearable Headset to Standard Automated Perimetry. J. Glaucoma 2023, 32, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razeghinejad, R.; Gonzalez-Garcia, A.; Myers, J.S.; Katz, L.J. Preliminary Report on a Novel Virtual Reality Perimeter Compared with Standard Automated Perimetry. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 30, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berneshawi, A.R.; Shue, A.; Chang, R.T. Glaucoma Home Self-Testing Using VR Visual Fields and Rebound Tonometry Versus In-Clinic Perimetry and Goldmann Applanation Tonometry: A Pilot Study. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Alvarez-Falcón, S.; El-Dairi, M.; Freedman, S.F. Performance of virtual reality game–based automated perimetry in patients with childhood glaucoma. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2023, 27, 325.e1–325.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, V.; Sankhe, P.; Haldipurkar, S.S.; Haldipurkar, T.; Dhamankar, R.; Kashelkar, P.; Shah, D.; Mhatre, P.; Setia, M.S. Diagnostic Performance of the PalmScan VF2000 Virtual Reality Visual Field Analyzer for Identification and Classification of Glaucoma. J. Ophthalmic Vis. Res. 2022, 17, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.K.; Tran, E.M.; Yan, W.M.; Kosaraju, R.; Sun, Y.; Chang, R.T. Comparing a Head-Mounted Smartphone Visual Field Analyzer to Standard Automated Perimetry in Glaucoma: A Prospective Study. J. Glaucoma 2024, 33, 742–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chia, Z.K.; Kong, A.W.; Turner, M.L.; Saifee, M.; Damato, B.E.; Backus, B.T.; Blaha, J.J.; Schuman, J.S.; Deiner, M.S.; Ou, Y. Assessment of Remote Training, At-Home Testing, and Test-Retest Variability of a Novel Test for Clustered Virtual Reality Perimetry. Ophthalmol. Glaucoma 2024, 7, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesfin, Y.; Kong, A.; Backus, B.T.; Deiner, M.; Ou, Y.; Oatts, J.T. Pilot study comparing a new virtual reality–based visual field test to standard perimetry in children. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2024, 28, 103933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, D.E.; Savatovsky, E.J.; O’Brien, R.C.; Vanner, E.A.; Munshi, H.K.M.; Pham, A.H.; Grajewski, A.L. Reliability of Visual Field Testing in a Telehealth Setting Using a Head-Mounted Device: A Pilot Study. J. Glaucoma 2024, 33, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, J.A.; Deiner, M.; Nguyen, A.; Wollstein, G.; Damato, B.; Backus, B.T.; Wu, M.; Schuman, J.S.; Ou, Y. Virtual Reality Oculokinetic Perimetry Test Reproducibility and Relationship to Conventional Perimetry and OCT. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2022, 2, 100105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spofforth, J.; Codina, C.; Bjerre, A. Is the ‘visual fields easy’ application a useful tool to identify visual field defects in patients who have suffered a stroke? Ophthalmol. Res. Int. J. 2017, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Device | Reference | Journal | Population Tested | HFA Protocol | Key Findings Related to Validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heru | Johnson et al. (2023) [25] | JOG | 71 glaucoma patients and 18 healthy adults (18–88 yo). | SITA Standard 24-2 | Mean Deviation: r = 0.94, ICC = 0.97 (95% CI: 0.94–0.98). Mean Sensitivity: r = 0.95, ICC = 0.97 (95% CI: 0.94–0.98). Pattern Standard Deviation: r = 0.89, ICC = 0.93 (95% CI: 0.89–0.95). |

| Olleyes VisuALL | Berneshawi et al. (2024) [27] | TVST | 9 glaucoma patients (60.2 ± 16.4 yo). | SITA Standard 24-2 | Mean Deviation: r = 0.88, ICC = 0.95 (95% CI: 0.88–0.98), CCC = 0.89 (95% CI: 0.75–0.96). Pattern Standard Deviation: r = 0.80, ICC = 0.84 (95% CI: 0.65–0.93), CCC = 0.73 (95% CI: 0.50–0.86). |

| Razeghinejad et al. (2021) [26] | JOG | 26 glaucoma patients and 25 healthy adults (23–86 yo). | SITA Standard 24-2 | Mean Sensitivity (glaucoma group): r = 0.80. Mean Sensitivity (control group): r = 0.50. | |

| Wang et al. (2023) [28] | JAAPOS | 38 children with glaucoma (14.1 ± 3.6 yo). | SITA Standard 24-2 | Mean Deviation: r = 0.68. Pattern Standard Deviation: r = 0.78. Point-by-point sensitivity: r = 0.63. Foveal sensitivity: r = 0.59. | |

| Griffin et al. (2024) [17] | JCGP | 24 glaucoma patients (18–88 yo). | SITA Standard 24-2 | Mean Deviation: r = 0.87. Mild glaucoma (slope = 1.1, r = 0.64), moderate glaucoma (slope = 0.9, r = 0.67), severe glaucoma (slope = 0.5, r = 0.44). | |

| Groth et al. (2023) [19] | TVST | 50 healthy children (8–17 yo). | SITA Standard 24-2 | Mean threshold sensitivity: r = 0.39, slope = 0.75 (95% CI: 0.62–0.90), intercept = 8.15 (95% CI: 3.45–12.06). Pointwise threshold sensitivity: r = 0.11, slope = 0.89 (95% CI: 0.87–0.92), intercept = 3.68 (95% CI: 2.91–4.44). | |

| PalmScan VF2000 | Wang et al. (2024) [30] | JOG | 51 glaucoma patients (26–85 yo). | SITA Standard 24-2 | Global MD and PSD values showed small average differences (+0.62 ± 0.26 dB and −1.00 ± 0.24 dB, respectively). There was wide variability across quadrants (MD difference range: −6.58 to +11.43 dB). |

| Shetty et al. (2022) [29] | JOVR | 57 glaucoma patients and 40 healthy adults (51.3 ± 14.9 yo). | SITA Standard 24-2 | The general agreement for the classification of glaucoma was 0.63 (95% CI: 0.56–0.78). For mild glaucoma was 0.76 (95% CI: 0.61–0.92), for moderate glaucoma was 0.37 (0.14–0.60), and for severe glaucoma was 0.70 (95% CI: 0.55–0.85). | |

| Radius | Bradley et al. (2024) [12] | TVST | 100 glaucoma or suspect glaucoma patients (26–84 yo). | SITA Standard 24-2 | Mean deviation: r = 0.94, slope = 0.48, intercept = −2.08 |

| Virtual Field | Phu et al. (2024) [18] | OPO | 54 glaucoma patients and 41 healthy adults (35–80 yo). | SITA Standard 24-2 | Mean Deviation: r = 0.87 (slope = 0.86); ICC = 0.86. Pattern Standard Deviation: r = 0.94 (slope = 1.63), ICC = 0.82. Pointwise sensitivity: r = 0.78 (slope = 0.85); ICC = 0.47. |

| Virtual Vision | McLaughlin et al. (2024) [33] | JOG | 11 patients with stable visual field defects (14–79 yo) and 10 healthy adults (60–65 yo). | SITA Standard 24-2 | Cohort with stable defects showed better agreement (p = 0.79) than those reported by the cohort without ocular disease (p = 0.02). No correlation coefficients (e.g., r, ICC) were reported. The level of agreement was assessed using non-parametric clustered Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. |

| Device | Reference | Journal | Population Tested | HFA Protocol | Key Findings Related to Validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PalmScan VF2000 | Wang et al. (2024) [30] | JOG | 51 glaucoma patients (26–85 yo). | SITA Standard 24-2 | Global MD and PSD values showed small average differences (+0.62 ± 0.26 dB and −1.00 ± 0.24 dB, respectively). There was wide variability across quadrants (MD difference range: −6.58 to +11.43 dB). |

| Shetty et al. (2022) [29] | JOVR | 57 glaucoma patients and 40 healthy adults (51.3 ± 14.9 yo). | SITA Standard 24-2 | The general agreement for the classification of glaucoma was 0.63 (95% CI: 0.56–0.78). For mild glaucoma was 0.76 (95% CI: 0.61–0.92), for moderate glaucoma was 0.37 (0.14–0.60), and for severe glaucoma was 0.70 (95% CI: 0.55–0.85). | |

| Vivid Vision | Mesfin et al. (2024) [32] | JAAPOS | 23 pediatric patients (12.9 ± 3.1 yo) with glaucoma, glaucoma suspect, or ocular hypertension. | SITA Fast or Standard 24-2 | The level of correlation was statistically insignificant, with the only exception of a moderate correlation between HFA mean sensitivity and VVP fraction seen score (r = 0.48; p = 0.02), using only reliable HFA tests. |

| Greenfield et al. (2022) [34] | OS | 7 glaucoma patients (64.6 ± 11.4 yo) and 5 with suspected glaucoma (61.8 ± 6.5 yo). | SITA Standard 24-2. | Correlation between mean sensitivity measurements from the VVP Swift with mean deviation measurements taken by the HVF examination was r = 0.86 (95% CI, 0.70–0.94), slope = 0.46, intercept = 26.2. | |

| Chia et al. (2024) [31] | OG | 36 eyes from 19 adults with glaucoma (62.2 ± 10.8 yo). | SITA Standard 24-2. | The level of correlation for mean sensitivity in moderate-to-advanced glaucoma eyes was r = 0.87, whereas the level of correlation was r = 0.67 when including all eyes. |

| Device | Reference | Journal | Population Tested | HFA Protocol | Key Findings Related to Validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced Vision Analyzer | Narang et al. (2024) [22] | JOG | 80 glaucoma patients (54.4 ± 14.7 yo) and 58 healthy adults (35.8 ± 19.3 yo). | SITA Fast 24-2 | Mean deviation: r = 0.91 (slope = 0.92, intercept = 0.28), ICC = 0.91 (controls = 0.45; glaucoma = 0.92). Mean sensitivity: r = 0.91 (slope = 0.96, intercept = 0.38), ICC = 0.92 (controls = 0.61; glaucoma = 0.92). Pattern standard deviation: r = 0.73 (slope = 0.75, intercept = 1.83), ICC = 0.87 (controls = 0.05; glaucoma = 0.89). |

| Narang et al. (2023) [23] | OS | 66 glaucoma patients (61.1 ± 14.5 yo), 36 healthy controls (41.7 ± 15.9 yo), and 10 glaucoma suspects (51.4 ± 11.2 yo). | SITA Standard 10-2 | Mean sensitivity: r = 0.96 (slope = 0.92) Mean deviation: r = 0.95 (slope = 0.93) Pattern standard deviation: r = 0.97 (slope = 1.01) | |

| Narang et al. (2021) [20] | OS | 75 glaucoma patients (38.2 ± 15.6 yo) and 85 healthy adults (56.7 ± 13.2 yo). | SITA Standard 24-2 | Mean deviation: r = 0.88 (slope = 0.84, intercept = 0.54), ICC = 0.88 (controls = 0.18; glaucoma = 0.93). Mean sensitivity: r = 0.79 (slope = 0.58, intercept = 1.58), ICC = 0.89 (controls = 0.50; glaucoma = 0.90). Pattern standard deviation: ICC = 0.75 (controls = 0.37; glaucoma = 0.74). | |

| C3 field Analyzer | Odayappan et al. (2023) [24] | JNO | 33 neuro-ophthalmic patients (49.0 ± 14.7 yo) and 95 controls (49.8 ± 9.2 yo). | SITA Standard 30-2 | Overall correlation of field defect patterns was 69.5% when including all patients. In hemianopia cases, the level of correlation was 87.5%. |

| Mees et al. (2020) [21] | JOG | 62 glaucoma patients (54.2 ± 9.3 yo) and 95 healthy adults (49.8 ± 9.2 yo). | SITA Standard 24-2 | Number of missed CFA stimuli correlated with HFA mean deviation (r = −0.62) and pattern standard deviation (r = 0.36). AUC for detecting glaucoma was 0.78 for early/moderate cases and 0.87 for advanced glaucoma. Only 38% of ≤18 dB HFA defects were detected at the same location. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vera, J.; Glazier, A.N.; Dunbar, M.T.; Ripkin, D.; Nafey, M. Evaluating the Clinical Validity of Commercially Available Virtual Reality Headsets for Visual Field Testing: A Systematic Review. Vision 2025, 9, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9040080

Vera J, Glazier AN, Dunbar MT, Ripkin D, Nafey M. Evaluating the Clinical Validity of Commercially Available Virtual Reality Headsets for Visual Field Testing: A Systematic Review. Vision. 2025; 9(4):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9040080

Chicago/Turabian StyleVera, Jesús, Alan N. Glazier, Mark T. Dunbar, Douglas Ripkin, and Masoud Nafey. 2025. "Evaluating the Clinical Validity of Commercially Available Virtual Reality Headsets for Visual Field Testing: A Systematic Review" Vision 9, no. 4: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9040080

APA StyleVera, J., Glazier, A. N., Dunbar, M. T., Ripkin, D., & Nafey, M. (2025). Evaluating the Clinical Validity of Commercially Available Virtual Reality Headsets for Visual Field Testing: A Systematic Review. Vision, 9(4), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9040080