Case Series: Reactivation of Herpetic Keratitis After COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination During Herpetic Prophylaxis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Reports

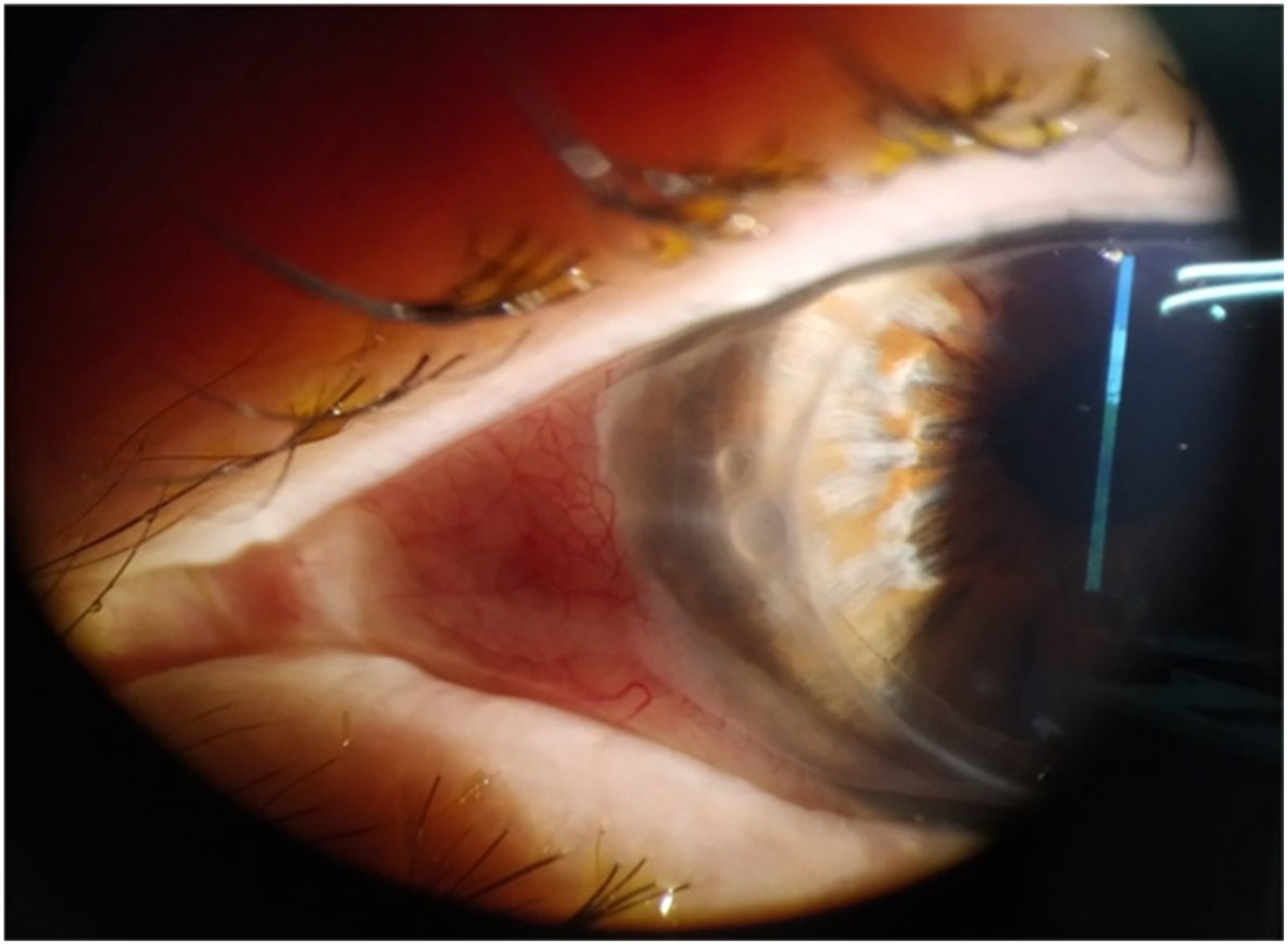

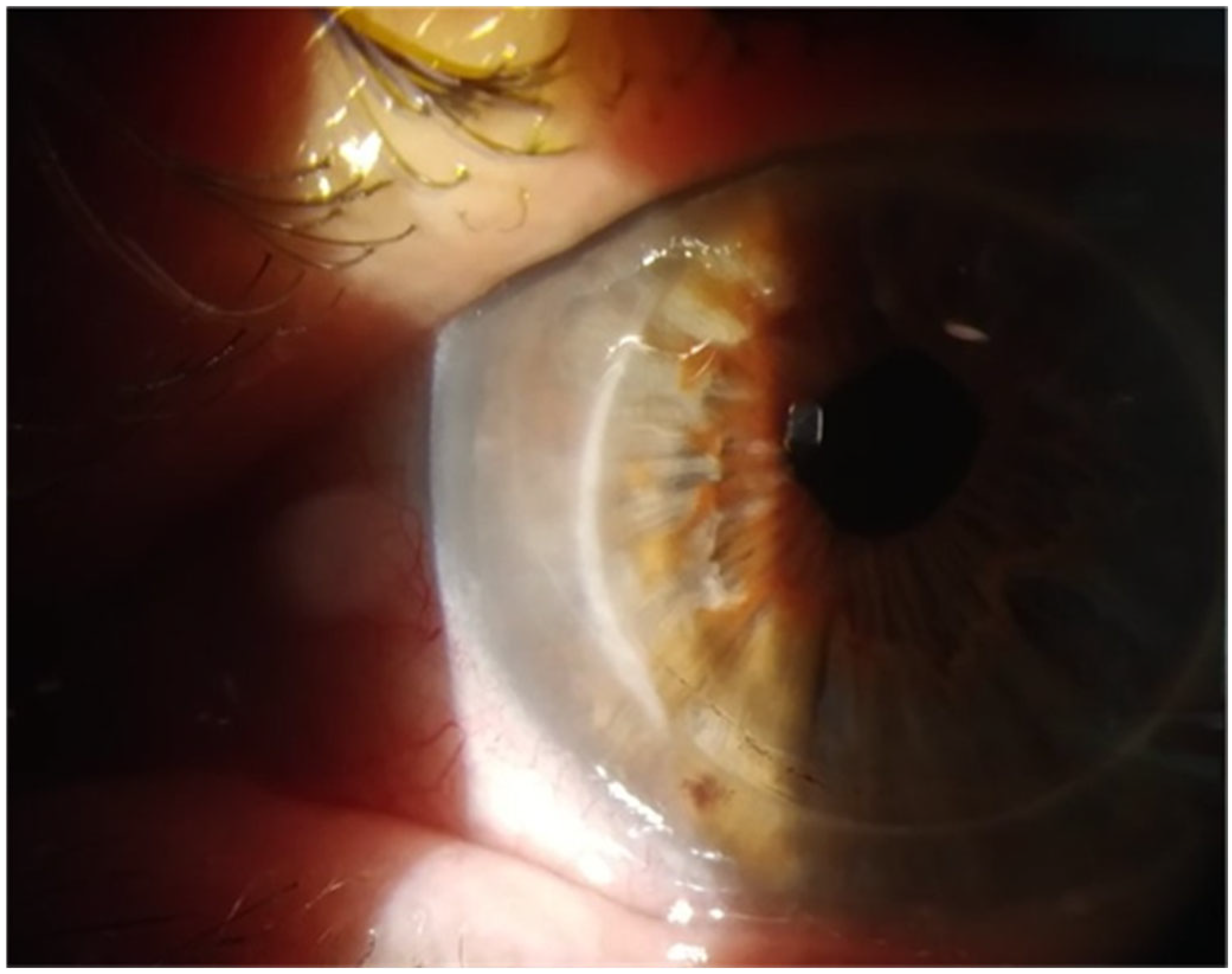

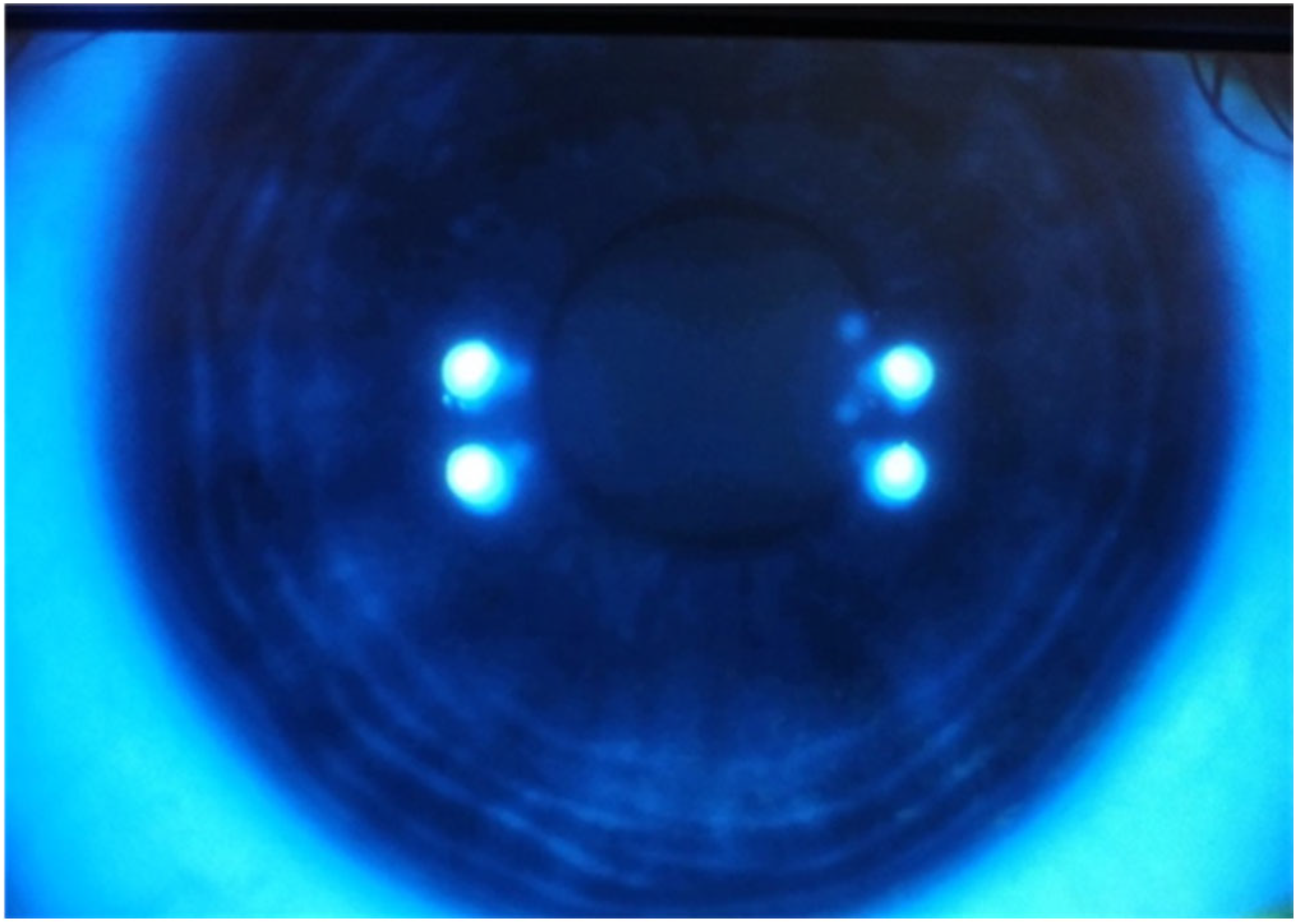

2.1. Case 1

2.2. Case 2

3. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nicoll, M.P.; Proença, J.T.; Efstathiou, S. The Molecular Basis of Herpes Simplex Virus Latency. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 36, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, D.P.; Clement, C.; Arceneaux, R.L.; Bhattacharjee, P.S.; Huq, T.S.; Hill, J.M. Ocular Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1: Is the Cornea a Reservoir for Viral Latency or a Fast Pit Stop? Cornea 2011, 30, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsatsos, M.; MacGregor, C.; Athanasiadis, I.; Moschos, M.M.; Hossain, P.; Anderson, D. Herpes Simplex Virus Keratitis: An Update of the Pathogenesis and Current Treatment with Oral and Topical Antiviral Agents. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2016, 44, 824–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoeger, T.; Adler, H. “Novel” Triggers of Herpesvirus Reactivation and Their Potential Health Relevance. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson-May, J.; Rothwell, A.; Rashid, M. Reactivation of Herpes Simplex Keratitis Following Vaccination for COVID-19. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, e245792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhalifah, M.I.; Alsobki, H.E.; Alwael, H.M.; Al Fawaz, A.M.; Al-Mezaine, H.S. Herpes Simplex Virus Keratitis Reactivation after SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 MRNA Vaccination: A Report of Two Cases. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2021, 29, 1238–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.E.; Ahn, S.H.; Jeong, C.Y.; Kim, J.S.; You, I.C. Herpesviral Keratitis Following COVID-19 Vaccination: Analysis of NHIS Database in Korea. Cornea 2025, 44, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawahara, A. Herpes Simplex Keratitis and Vitamin D Receptor Agonist: Two Case Reports. Diseases 2025, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassman, L.M.; DiLoreto, D.A. Immunologic Factors May Play a Role in Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Reactivation in the Brain and Retina after Influenza Vaccination. IDCases 2016, 6, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadasivan, S.; Zanin, M.; O’Brien, K.; Schultz-Cherry, S.; Smeyne, R.J. Induction of Microglia Activation after Infection with the Non-Neurotropic A/CA/04/2009 H1N1 Influenza Virus. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, T.J.; Ta, C.N. Reactivation of Herpes Zoster Keratitis Following Shingrix Vaccine. Case Rep. Ophthalmol. 2022, 13, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilhelmus, K.R.; Beck, R.W.; Moke, P.S.; Dawson, C.R.; Barron, B.A.; Jones, D.B.; Kaufman, H.E.; Kurinij, N.; Stulting, R.D.; Sugar, J.; et al. Acyclovir for the Prevention of Recurrent Herpes Simplex Virus Eye Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, A.L.; Pavan-Langston, D.; Asbell, P.A. Long-Term Oral Acyclovir Therapy: Effect on Recurrent Infectious Herpes Simplex Keratitis in Patients with and without Grafts. Ophthalmology 1996, 103, 1399–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Huang, R.; Sy, L.S.; Glenn, S.C.; Ryan, D.S.; Morrissette, K.; Shay, D.K.; Vazquez-Benitez, G.; Glanz, J.M.; Klein, N.P.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccination and Non-COVID-19 Mortality Risk—Seven Integrated Health Care Organizations, United States, December 14, 2020-July 31, 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 1520–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, X.L.; Betzler, B.K.; Testi, I.; Ho, S.L.; Tien, M.; Ngo, W.K.; Zierhut, M.; Chee, S.P.; Gupta, V.; Pavesio, C.E.; et al. Ocular Adverse Events After COVID-19 Vaccination. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2021, 29, 1216–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousseau, A.; Boutolleau, D.; Titier, K.; Bourcier, T.; Chiquet, C.; Weber, M.; Colin, J.; Gueudry, J.; M’Garrech, M.; Bodaghi, B.; et al. Recurrent Herpetic Keratitis despite Antiviral Prophylaxis: A Virological and Pharmacological Study. Antivir. Res. 2017, 146, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsatsos, M.; Prousali, E.; Karamitsos, A.; Ziakas, N. Case Series: Reactivation of Herpetic Keratitis After COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination During Herpetic Prophylaxis. Vision 2025, 9, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9030063

Tsatsos M, Prousali E, Karamitsos A, Ziakas N. Case Series: Reactivation of Herpetic Keratitis After COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination During Herpetic Prophylaxis. Vision. 2025; 9(3):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9030063

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsatsos, Michael, Efthymia Prousali, Athanasios Karamitsos, and Nikolaos Ziakas. 2025. "Case Series: Reactivation of Herpetic Keratitis After COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination During Herpetic Prophylaxis" Vision 9, no. 3: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9030063

APA StyleTsatsos, M., Prousali, E., Karamitsos, A., & Ziakas, N. (2025). Case Series: Reactivation of Herpetic Keratitis After COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination During Herpetic Prophylaxis. Vision, 9(3), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9030063