Perception and Decision-Making in Virtual Telepsychology Spaces and Professionals

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Indoor Space Perception

1.2. The Role of Professional Appearance

1.3. Justification

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Ethical Approval

2.2. Sample

2.3. Images Creation

2.4. Instrument

2.5. Procedure

2.6. Data Analysis

- Analyzing the ANOVA for time responses and chi-square tables for categorical variables to see what factors influenced the user when choosing an online environment or taking any option.

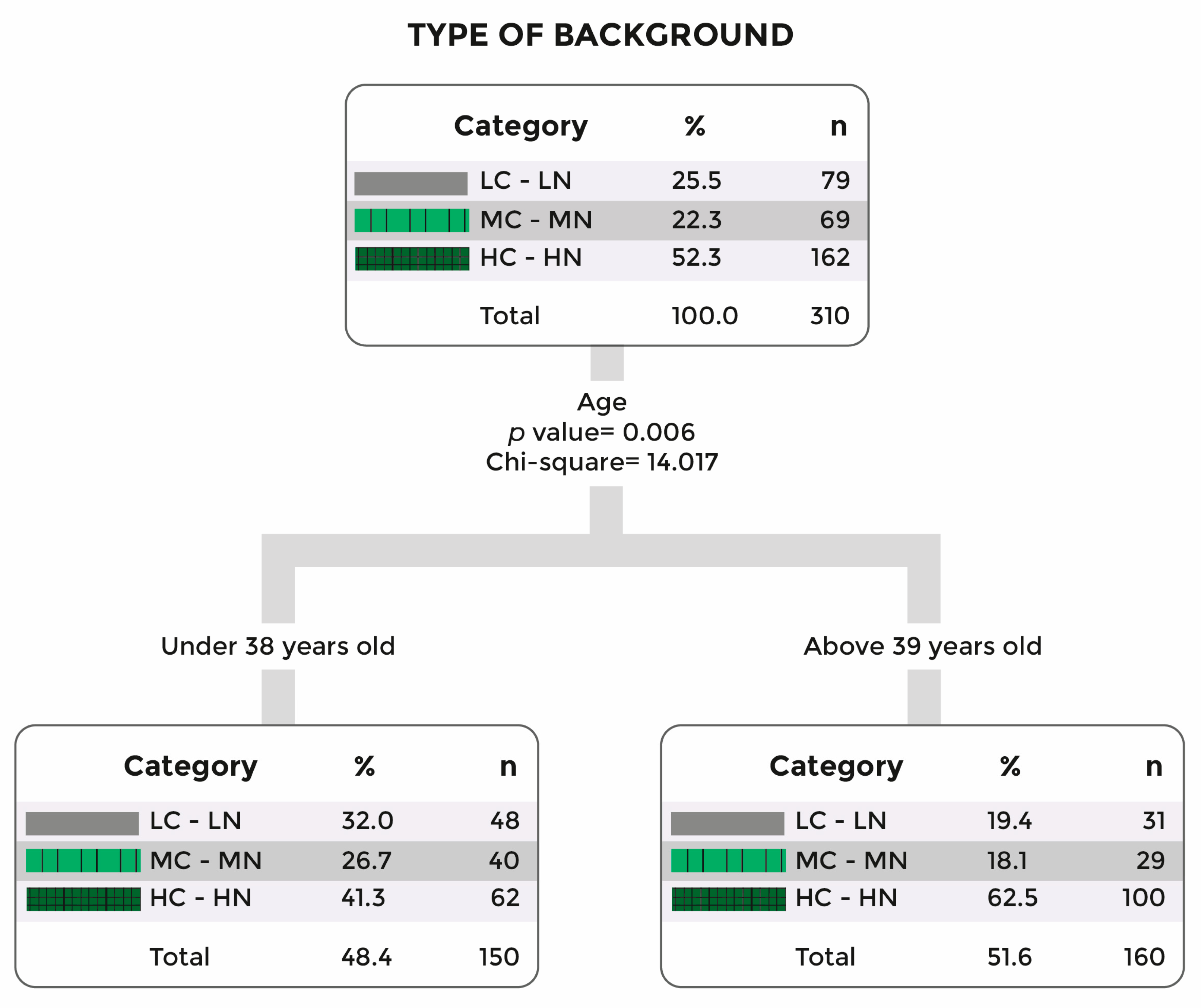

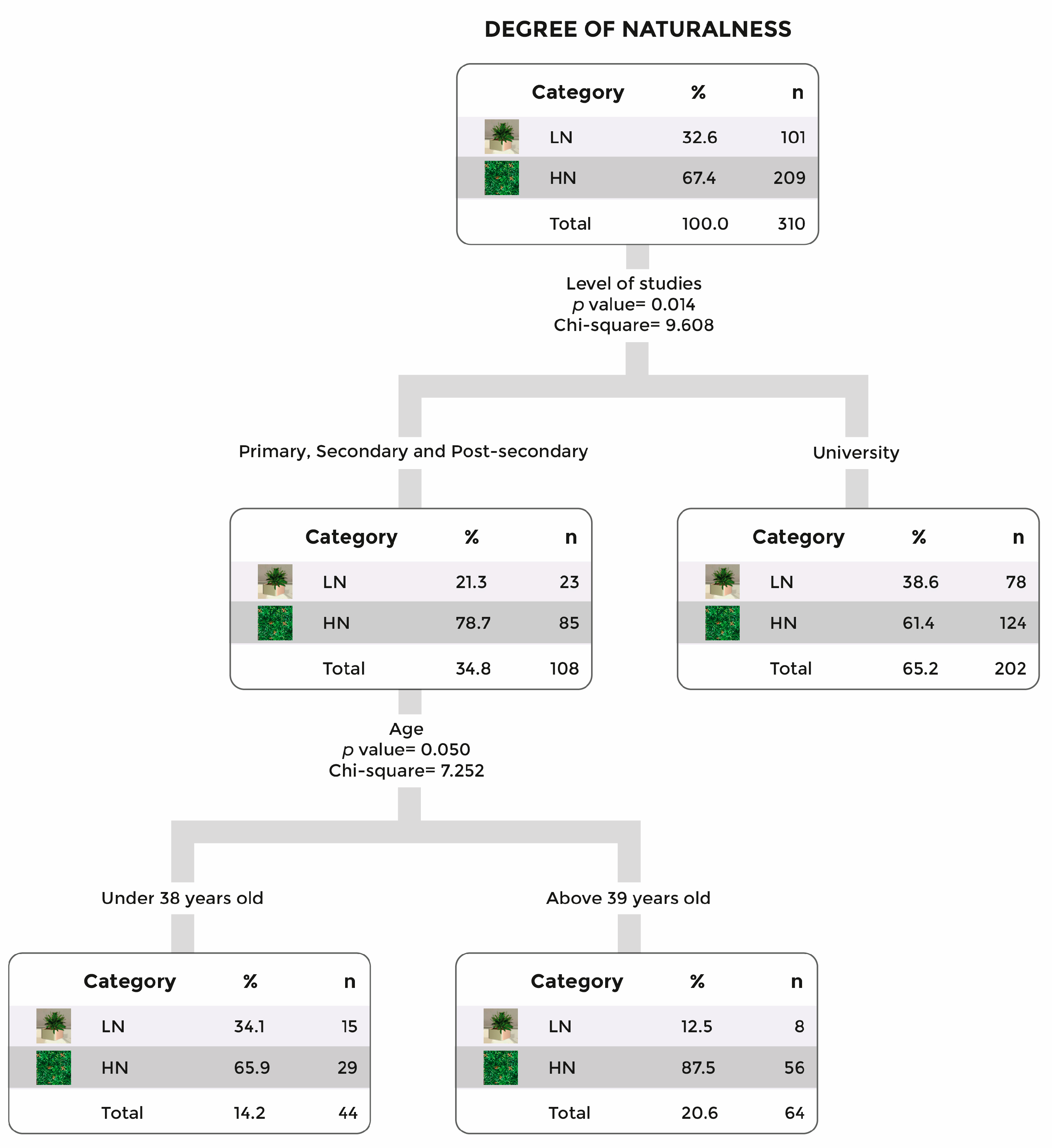

- Grouping individuals for each photomontage through decision trees to take their profile and characteristics into consideration.

- Finally, calculating the probability that a given user uses the different proposed environments thanks to logistic regression models.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Therapist Appearance

3.3. Decision-Making for Virtual Environments in Telepsychology

3.4. Logistic Regression for Choices

4. Discussion

4.1. According to Appearance of the Therapist

4.2. According to Environmental Images

4.3. Limitations and Prospective

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pierce, B.S.; Perrin, P.B.; Tyler, C.M.; McKee, G.B.; Watson, J.D. The COVID-19 Telepsychology Revolution: A National Study of Pandemic-Based Changes in U.S. Mental Health Care Delivery. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychological Association. Guidelines for the Practice of Telepsychology. Am. Psychol. 2013, 68, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancuso, F. La terapia online: Innovazione e integrazione tecnologica nella pratica clinica. Cogn. Clin. 2020, 16, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, F.; Whitten, P. Systematic Review of Studies of Patient Satisfaction with Telemedicine. BMJ 2000, 320, 1517–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morón, J.J.M.; Aguayo, L.V. La psicoterapia on-line ante los retos y peligros de la intervención psicológica a distancia. Apunt. Psicol. 2018, 36, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jens, K.; Gregg, J.S. How Design Shapes Space Choice Behaviors in Public Urban and Shared Indoor Spaces—A Review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 65, 102592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlmeier, A.; Feld, S. Learning Indoor Space Perception. J. Locat. Based Serv. 2018, 12, 179–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custers, P.; de Kort, Y.; IJsselsteijn, W.; de Kruiff, M. Lighting in Retail Environments: Atmosphere Perception in the Real World. Light. Res. Technol. 2010, 42, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, H.; Ou, D. A Comparative Field Study of Indoor Environmental Quality in Two Types of Open-Plan Offices: Open-Plan Administrative Offices and Open-Plan Research Offices. Build. Environ. 2019, 148, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolé Fajardo, M.L.; Higuera-Trujillo, J.L.; Llinares, C. Lighting, Colour and Geometry: Which Has the Greatest Influence on Students’ Cognitive Processes? Front. Archit. Res. 2023, 12, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H.; Moon, J.W.; Kim, S. Analysis of Occupants’ Visual Perception to Refine Indoor Lighting Environment for Office Tasks. Energies 2014, 7, 4116–4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikookar, N.; Sawyer, A.O.; Goel, M.; Rockcastle, S. Investigating the Impact of Combined Daylight and Electric Light on Human Perception of Indoor Spaces. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayetoglu, M.L.; Yildirim, K.; Akalin, A. The Effects of Color and Light on Indoor Wayfinding and the Evaluation of the Perceived Environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odabaşioğlu, S.; Olguntürk, N. Effects of Coloured Lighting on the Perception of Interior Spaces. Percept. Mot. Skills 2015, 120, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Castell, C.; Hecht, H.; Oberfeld, D. Which Attribute of Ceiling Color Influences Perceived Room Height? Hum. Factors 2018, 60, 1228–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Frumento, S.; Nese, M.; Predieri, I. Interior Color and Psychological Functioning in a University Residence Hall. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Ji, J.; Chen, H.; Ye, C. Optimal Color Design of Psychological Counseling Room by Design of Experiments and Response Surface Methodology. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, F.; Leng, X. Colour Here, There, and in-between—Placemaking and Wayfinding in Mental Health Environments. Color Res. Appl. 2021, 46, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritterlfeld, U.; Cupchik, G.C. Perceptions of Interior Spaces. J. Environ. Psychol. 1996, 16, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, L.; Adams, J.; Deal, B.; Kweon, B.S.; Tyler, E. Plants in the Workplace: The Effects of Plant Density on Productivity, Attitudes, and Perceptions. Environ. Behav. 1998, 30, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, S.; Suzuki, N. Effects of the Foliage Plant on Task Performance and Mood. J. Environ. Psychol. 2002, 22, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.; Essah, E.; Blanusa, T.; Beaman, C.P. The Appearance of Indoor Plants and Their Effect on People’s Perceptions of Indoor Air Quality and Subjective Well-Being. Build. Environ. 2022, 219, 109151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuis, M.; Knight, C.; Postmes, T.; Haslam, S.A. The Relative Benefits of Green versus Lean Office Space: Three Field Experiments. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2014, 20, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moscoso, C.; Chamilothori, K.; Wienold, J.; Andersen, M.; Matusiak, B. Window Size Effects on Subjective Impressions of Daylit Spaces: Indoor Studies at High Latitudes Using Virtual Reality. LEUKOS 2021, 17, 242–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goethe, O.; Sørum, H.; Johansen, J. The Effect or Non-Effect of Virtual Versus Non-Virtual Backgrounds in Digital Learning. In Human Interaction, Emerging Technologies and Future Systems V; Ahram, T., Taiar, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.H.M.; Qiu, L.; Lam, J. An Investigation into the Stress-Buffering Effects of Nature Virtual Backgrounds in Video Calls. In Applied Psychology Readings; Moore, B., Murray, E., Winslade, M., Tan, L.-M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanica, A.; Fossat, Y. Effects of Nature Virtual Backgrounds on Creativity during Videoconferencing. Think. Ski. Creat. 2022, 43, 100976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharam, L.A.; Mayer, K.M.; Baumann, O. Design by Nature: The Influence of Windows on Cognitive Performance and Affect. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 85, 101923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hester, N.; Hehman, E. Dress Is a Fundamental Component of Person Perception. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 27, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hareli, S.; Hanoch, Y.; Elkabetz, S.; Hess, U. Dressed Emotions: How Attire and Emotion Expressions Influence First Impressions. J. Nonverbal Behav. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda-Vossos, A.; Brooks, R.C.; Dixson, B.J.W. The Interplay Between Economic Status and Attractiveness, and the Importance of Attire in Mate Choice Judgments. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, N.; Pine, K.; Orakçıoğlu, I.; Fletcher, B. The Influence of Clothing on First Impressions. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2013, 17, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuhisa, T.; Takahashi, N.; Takahashi, K.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Aomatsu, M.; Sato, J.; Mercer, S.W.; Ban, N. Effect of Physician Attire on Patient Perceptions of Empathy in Japan: A Quasi-Randomized Controlled Trial in Primary Care. BMC Fam. Pract. 2021, 22, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brase, G.L.; Richmond, J. The White–Coat Effect: Physician Attire and Perceived Authority, Friendliness, and Attractiveness. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 2469–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A.; Chan, P.S.; Wilson, E. What to Wear? The Influence of Attire on the Perceived Professionalism of Dentists and Lawyers. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 43, 1838–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, S.M.; Busby, D.M. Therapist Physical Attractiveness: An Unexplored Influence on Client Disclosure. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 1998, 24, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitmeyer, J.R.; Goldsmith, E.B. Attire, an Influence on Perceptions of Counselors’ Characteristics. Percept. Mot. Skills 1990, 70, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfender, E.; and Caplan, S. Nonverbal Immediacy Cues and Impression Formation in Video Therapy. Couns. Psychol. Q. 2023, 36, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Business Development Teams—Market.Us. Telemedicine Market Size to Surpass USD 590.9 Billion in Value by 2032, at CAGR of 25.7%—Market.Us. Available online: https://www.globenewswire.com/en/news-release/2023/02/27/2616144/0/en/Telemedicine-Market-Size-to-Surpass-USD-590-9-billion-in-value-by-2032-at-CAGR-of-25-7-Market-us.html (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Worlikar, H.; Coleman, S.; Kelly, J.; O’Connor, S.; Murray, A.; McVeigh, T.; Doran, J.; McCabe, I.; O’Keeffe, D. Mixed Reality Platforms in Telehealth Delivery: Scoping Review. JMIR Biomed. Eng. 2023, 8, e42709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCord, C.; Bernhard, P.; Walsh, M.; Rosner, C.; Console, K. A Consolidated Model for Telepsychology Practice. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 76, 1060–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, N.; McDonald, C.; de Boer, K.; Brand, R.M.; Nedeljkovic, M.; Seabrook, L. Review of the Current Empirical Literature on Using Videoconferencing to Deliver Individual Psychotherapies to Adults with Mental Health Problems. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2021, 94, 854–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasgow, O.G.; Berman, J.S. Are Perceptions of the Psychotherapist Affected by the Audiovisual Quality of a Teletherapy Session? Psychother. Res. 2024, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, F.; Chang, S.; Mendoza, A.; Buchanan, G.; Van Dam, N. Exploring Technical Features to Enhance Control in Videoconferencing Psychotherapy: Quantitative Study on Clinicians’ Perspectives. J Med. Internet Res 2025, 27, e66904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, J.L. Identifying Digital Rhetoric in the Telemedicine User Interface. J. Tech. Writ. Commun. 2023, 53, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hames, J.L.; Bell, D.J.; Perez-Lima, L.M.; Holm-Denoma, J.M.; Rooney, T.; Charles, N.E.; Thompson, S.M.; Mehlenbeck, R.S.; Tawfik, S.H.; Fondacaro, K.M.; et al. Navigating Uncharted Waters: Considerations for Training Clinics in the Rapid Transition to Telepsychology and Telesupervision during COVID-19. J. Psychother. Integr. 2020, 30, 348–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, A.; Agha, Z.; Maglione, M.L.; Repp, A.; Ross, B.; Zuest, D.; Rice-Thorp, N.M.; Lohr, J.; Thorp, S.R. Videoconferencing Psychotherapy: A Systematic Review. Psychol. Serv. 2012, 9, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweiker, M.; Ampatzi, E.; Andargie, M.S.; Andersen, R.K.; Azar, E.; Barthelmes, V.M.; Berger, C.; Bourikas, L.; Carlucci, S.; Chinazzo, G.; et al. Review of Multi-domain Approaches to Indoor Environmental Perception and Behaviour. Build. Environ. 2020, 176, 106804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBain, R.K.; Schuler, M.S.; Qureshi, N.; Matthews, S.; Kofner, A.; Breslau, J.; Cantor, J.H. Expansion of Telehealth Availability for Mental Health Care After State-Level Policy Changes From 2019 to 2022. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2318045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgüzel, C.; Luca, D.; Wei, Z. The New Geography of Remote Jobs? Evidence from Europe; OECD: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, J.; Torous, J.; Nicholas, J.; Carney, R.; Pratap, A.; Rosenbaum, S.; Sarris, J. The Efficacy of Smartphone-Based Mental Health Interventions for Depressive Symptoms: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, A.; Torralba, A. Modeling the Shape of the Scene: A Holistic Representation of the Spatial Envelope. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2001, 42, 145–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, A.; Torralba, A. Chapter 2 Building the Gist of a Scene: The Role of Global Image Features in Recognition. In Progress in Brain Research; Martinez-Conde, S., Macknik, S.L., Martinez, L.M., Alonso, J.-M., Tse, P.U., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 155, pp. 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsson, B.; Hedblom, M. Biophilia Revisited: Nature versus Nurture. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2023, 38, 792–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiebel, T.; Gallinat, J.; Kühn, S. Testing the Biophilia Theory: Automatic Approach Tendencies towards Nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 79, 101725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Park, B.-J.; Lee, J.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Forest Walking Affects Autonomic Nervous Activity: A Population-Based Study. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangone, G.; Capaldi, C.A.; van Allen, Z.M.; Luscuere, P.G. Bringing Nature to Work: Preferences and Perceptions of Constructed Indoor and Natural Outdoor Workspaces. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. Cognitive Maps in Perception and Thought. In Image and Environment: Cognitive Mapping and Spatial Behavior; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 1973; pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Laird, P.N. The History of Mental Models. In Psychology of Reasoning; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2004; pp. 189–222. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. Aesthetics, Affect, and Cognition: Environmental Preference from an Evolutionary Perspective. Environ. Behav. 1987, 19, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.S.-H.; Lin, Y.-J. The Effect of Landscape Colour, Complexity and Preference on Viewing Behaviour. Landsc. Res. 2020, 45, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, H.; Luo, J.; Liu, Q.; Lan, Y. Landscape Design Intensity and Its Associated Complexity of Forest Landscapes in Relation to Preference and Eye Movements. Forests 2023, 14, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavdas, A.A.; Schirpke, U. Aesthetic Preference Is Related to Organized Complexity. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.C. Complexity and Mystery as Predictors of Interior Preferences. J. Inter. Des. 1993, 19, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Cha, S.H.; Koo, C.; Tang, S. The Effects of Indoor Plants and Artificial Windows in an Underground Environment. Build. Environ. 2018, 138, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanRullen, R.; Thorpe, S.J. The Time Course of Visual Processing: From Early Perception to Decision-Making. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2001, 13, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacy, J.M.; Brodsky, S.L. Effects of Therapist Attire and Gender. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. Train. 1992, 29, 486–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; van Prooijen, J.-W.; van Lange, P.A.M. Status Cues and Moral Judgment: Formal Attire Induces Moral Favoritism but Not for Hypocrites. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 19247–19263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, N.K. ‘Posh Music Should Equal Posh Dress’: An Investigation into the Concert Dress and Physical Appearance of Female Soloists. Psychol. Music 2010, 38, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, T.L.; Gorham, J.; Cohen, S.H.; Huffman, D. Fashion in the Classroom: Effects of Attire on Student Perceptions of Instructors in College Classes. Commun. Educ. 1996, 45, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.; Shafir, E.; Todorov, A. Economic Status Cues from Clothes Affect Perceived Competence from Faces. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurney, D.J.; Howlett, N.; Pine, K.; Tracey, M.; Moggridge, R. Dressing up Posture: The Interactive Effects of Posture and Clothing on Competency Judgements. Br. J. Psychol. 2017, 108, 436–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alós-Ferrer, C.; Garagnani, M. Who Likes It More? Using Response Times to Elicit Group Preferences in Surveys; Working Paper 422; University of Zurich, Department of Economics: Zurich, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadlen, M.N.; Kiani, R. Decision Making as a Window on Cognition. Neuron 2013, 80, 791–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Zeng, X.; Zhuo, Z.; Ye, B.; Fang, L.; Huang, Q.; Lai, P. The Impact of Landscape Complexity on Preference Ratings and Eye Fixation of Various Urban Green Space Settings. Urban For. Urban Green 2021, 66, 127411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houchens, N.; Saint, S.; Kuhn, L.; Ratz, D.; Engle, J.M.; Meddings, J. Patient Preferences for Telemedicine Video Backgrounds. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2411512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Puerto, G.; Rosselló, J.; Corradi, G.; Acedo-Carmona, C.; Munar, E.; Nadal, M. Preference for Curved Contours across Cultures. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2018, 12, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.S.B.T. Dual-Processing Accounts of Reasoning, Judgment, and Social Cognition. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 59, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.S.B.T. Reflections on Reflection: The Nature and Function of Type 2 Processes in Dual-Process Theories of Reasoning. Think. Reason. 2019, 25, 383–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stosic, M.D.; Duane, J.-N.; Durieux, B.N.; Sando, M.; Robicheaux, E.; Podolski, M.; Sanders, J.J.; Ericson, J.D.; Blanch-Hartigan, D. Patient Preference for Telehealth Background Shapes Impressions of Physicians and Information Recall: A Randomized Experiment. Telemed. E-Health 2022, 28, 1541–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| HEX (RGB) | Color Name |

|---|---|

| 0094de rgb (0, 148, 222) | Cerulean |

| #ae47e0 rgb (174, 71, 224) | Medium purple |

| #777777 rgb (119, 119, 119) | Boulder |

| #007cde rgb (0, 124, 222) | Lochmara |

| #028e74 rgb (2, 142, 116) | Observatory |

| #028d00 rgb (2, 141, 0) | Japanese laurel |

| #8a7500 rgb (138, 117, 0) | Olive |

| #d73c0c rgb (215, 60, 12) | Tia maria |

| #ce3e79 rgb (206, 62, 121) | Cabaret |

| Primary | Secondary | Post-Secondary | University | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies n (%) | 17 (5.5%) | 31 (10%) | 60 (19.4%) | 202 (65.2%) | |

| None | Low | Indifferent | Some | High | |

| Interest in psychological therapy | 15 (4.8%) | 11 (3.5%) | 31 (10%) | 131 (42.3%) | 122 (39.4%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lobato Rincón, L.-L.; Medina Sánchez, M.Á.; Tovar Bordón, R. Perception and Decision-Making in Virtual Telepsychology Spaces and Professionals. Vision 2025, 9, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9020043

Lobato Rincón L-L, Medina Sánchez MÁ, Tovar Bordón R. Perception and Decision-Making in Virtual Telepsychology Spaces and Professionals. Vision. 2025; 9(2):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9020043

Chicago/Turabian StyleLobato Rincón, Luis-Lucio, Maria Ángeles Medina Sánchez, and Rubén Tovar Bordón. 2025. "Perception and Decision-Making in Virtual Telepsychology Spaces and Professionals" Vision 9, no. 2: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9020043

APA StyleLobato Rincón, L.-L., Medina Sánchez, M. Á., & Tovar Bordón, R. (2025). Perception and Decision-Making in Virtual Telepsychology Spaces and Professionals. Vision, 9(2), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9020043