Eye Movement Latency Coefficient of Variation as a Predictor of Cognitive Impairment: An Eye Tracking Study of Cognitive Impairment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Cognitive Assessments

2.3. Eye Tracking Tasks

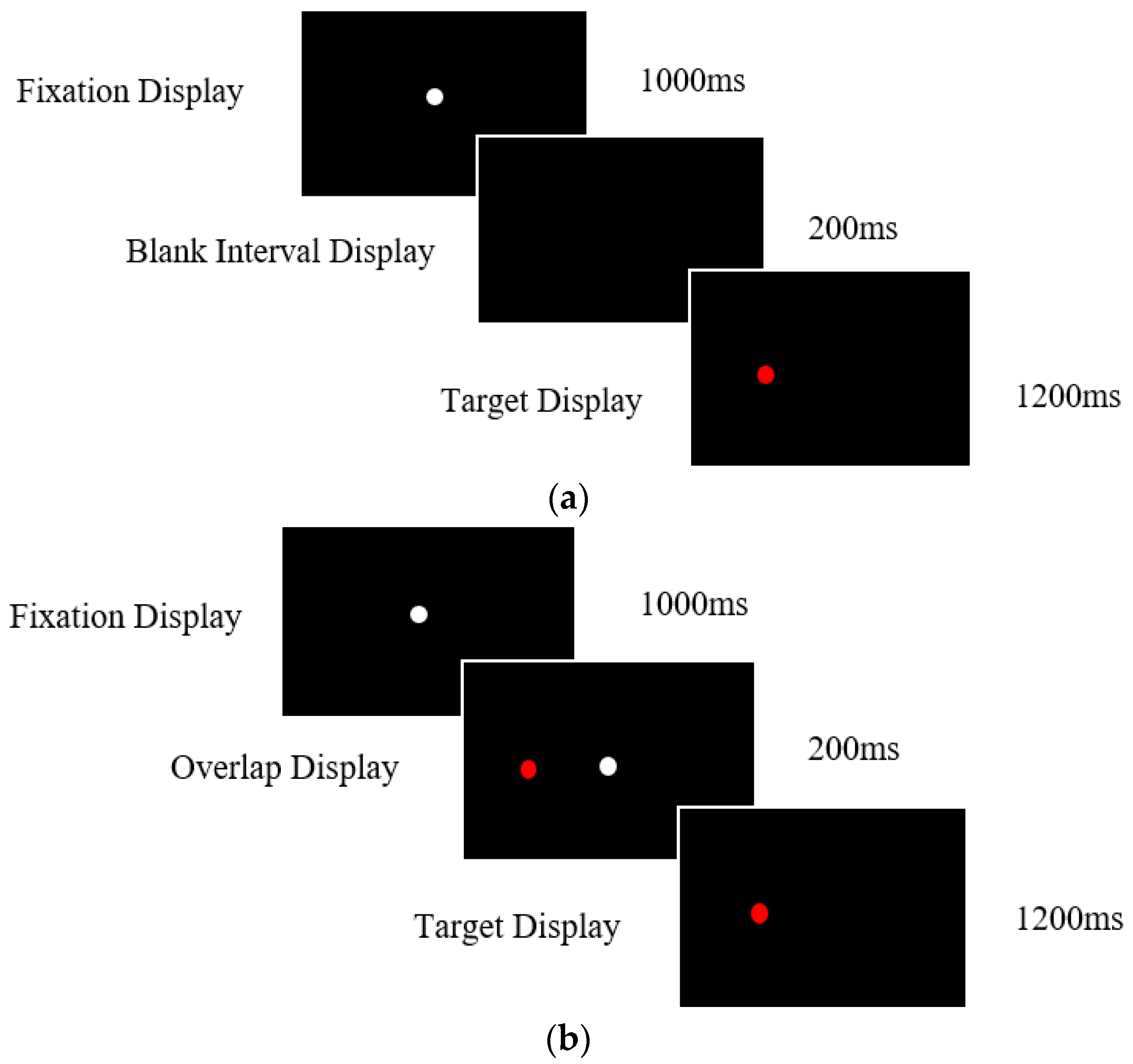

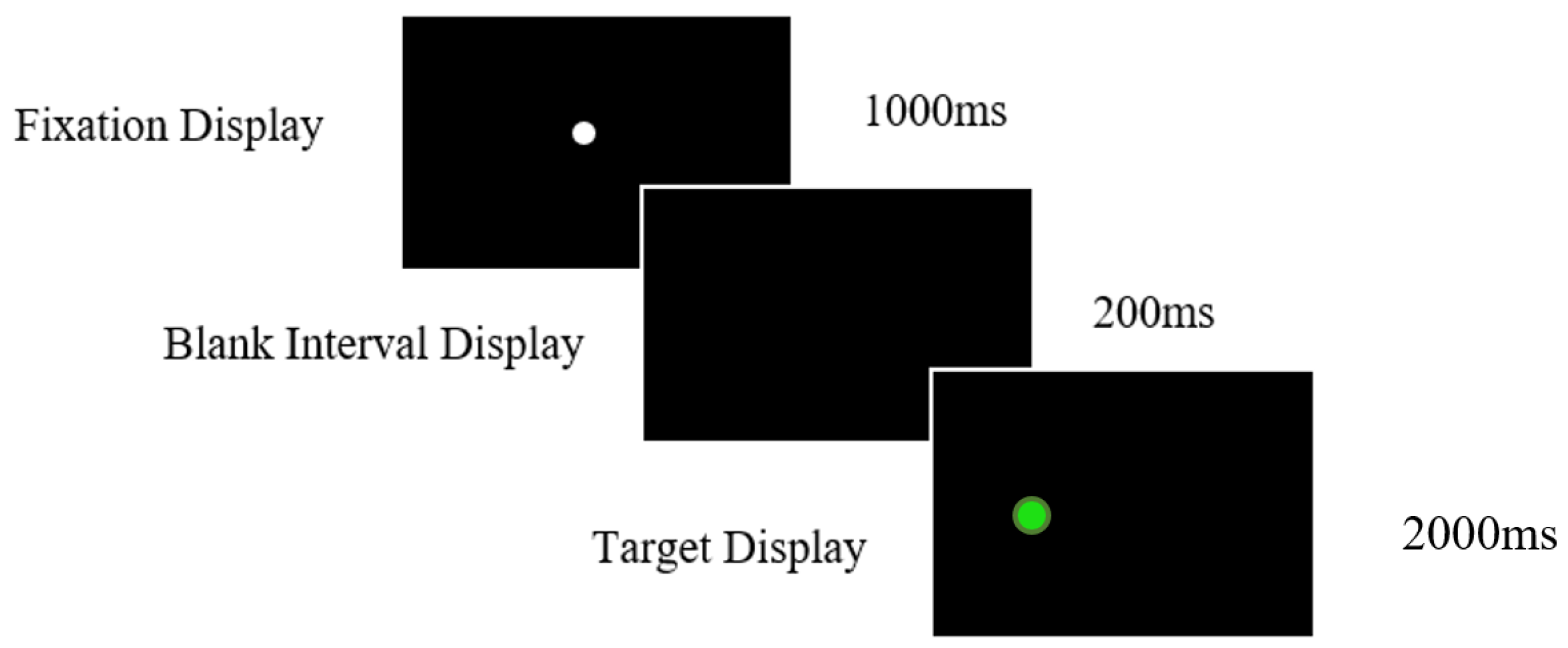

2.3.1. Prosaccade Task

2.3.2. Antisaccade Task

2.4. Data Processing

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Cognitive Assessments

3.2. Prosaccade Task—Gap Condition

3.2.1. Mean Reaction Times and Coefficient of Variation Group Effects

3.2.2. Correlations between Prosaccade Markers and Cognitive Assessments

3.3. Prosaccade Task—Overlap Condition

3.3.1. Mean Reaction Rimes and Coefficient of Variation Group Effects

3.3.2. Correlations between Prosaccade Markers and Cognitive Assessments Overlap

3.4. Antisaccade Task

3.4.1. Correct Trials Mean Reaction Times and Coefficient of Variation Group Effects

3.4.2. Correlations between Antisaccade Markers and Cognitive Assessments

3.5. Error Rates

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wolf, A.; Ueda, K. Contribution of Eye-Tracking to Study Cognitive Impairments Among Clinical Populations. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 590986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, Z.; Gu, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, P. The effectiveness of eye tracking in the diagnosis of cognitive disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokushige, S.-I.; Matsumoto, H.; Matsuda, S.-I.; Inomata-Terada, S.; Kotsuki, N.; Hamada, M.; Tsuji, S.; Ugawa, Y.; Terao, Y. Early detection of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease using eye tracking. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1123456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkoyun, M.; Koçoğlu, K.; Boz, H.E.; Keskinoğlu, P.; Akdal, G. Saccadic Eye Movements in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Longitudinal Study. J. Mot. Behav. 2023, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opwonya, J.; Doan, D.N.T.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, J.I.; Ku, B.; Kim, S.; Park, S.; Kim, J.U. Saccadic Eye Movement in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2022, 32, 193–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Readman, M.R.; Polden, M.; Gibbs, M.C.; Wareing, L.; Crawford, T.J. The Potential of Naturalistic Eye Movement Tasks in the Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molitor, R.J.; Ko, P.C.; Ally, B.A. Eye movements in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2015, 44, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacAskill, M.; Anderson, T.J. Eye movements in neurodegenerative diseases. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2016, 29, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, R.A.; Aisen, P.S.; Beckett, L.A.; Bennett, D.A.; Craft, S.; Fagan, A.M.; Phelps, C.H. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2011, 7, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, T.J. Alzheimer’s disease: Is the clue in the eyes? Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2013, 3, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, G.; Castro, L.R.; Schumacher, M.; Agamennoni, O.E. Diagnosis of mild Alzheimer disease through the analysis of eye movements during reading. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2015, 14, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, S.B.; Ettinger, U. The antisaccade task as a research tool in psychopathology: A critical review. Psychophysiology 2006, 43, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Ruiz, J.; Peltsch, A.; Alahyane, N.; Brien, D.C.; Coe, B.; Garcia, A.; Munoz, D.P. Age related prefrontal compensatory mechanisms for inhibitory control in the antisaccade task. Neuroimage 2018, 165, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, D.P.; Everling, S. Look away: The anti-saccade task and the voluntary control of eye movement. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004, 5, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, T.J.; Higham, S.; Mayes, J.; Dale, M.; Shaunak, S.; Lekwuwa, G. The role of working memory and attentional disengagement on inhibitory control: Effects of aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Age 2013, 35, 1637–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, A.D.; Baddeley, H.A.; Bucks, R.S.; Wilcock, G.K. Attentional control in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2001, 124, 1492–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltsch, A.; Hemraj, A.; Garcia, A.; Munoz, D.P. Saccade deficits in amnestic mild cognitive impairment resemble mild Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2014, 39, 2000–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Wang, T.; Su, N.; Xiao, S.; Kapoula, Z. Specific saccade deficits in patients with Alzheimer’s disease at mild to moderate stage and in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Age 2012, 35, 1287–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Wang, T.; Su, N.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, S.; Kapoula, Z. Long Latency and High Variability in Accuracy-Speed of Prosaccades in Alzheimer’s Disease at Mild to Moderate Stage. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. Extra 2011, 1, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polden, M.; Wilcockson, T.D.; Crawford, T.J. The disengagement of visual attention: An eye-tracking study of cognitive impairment, ethnicity and age. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polden, M.; Crawford, T.J. Active visual inhibition is preserved in the presence of a distracter: A cross-cultural, ageing and dementia study. Cortex 2021, 142, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, T.J.; Parker, E.; Solis-Trapala, I.; Mayes, J. Is the relationship of prosaccade reaction times and antisaccade errors mediated by working memory? Exp. Brain Res. 2010, 208, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, R.C. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J. Intern. Med. 2004, 256, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glynn, K.; O’Callaghan, M.; Hannigan, O.; Bruce, I.; Gibb, M.; Coen, R.; Green, E.; Lawlor, B.; Robinson, D. Clinical utility of mild cognitive impairment subtypes and number of impaired cognitive domains at predicting progression to dementia: A 20-year retrospective study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 36, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, P.; Jungwirth, S.; Zehetmayer, S.; Weissgram, S.; Hoenigschnabl, S.; Gelpi, E.; Krampla, W.; Tragl, K.H. Conversion from subtypes of mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer dementia. Neurology 2007, 68, 288–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, A.; Tardiff, S.; Dye, C.; Arrighi, H.M. Rate of conversion from prodromal Alzheimer’s disease to Alzheimer’s dementia: A systematic review of the literature. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. Extra 2013, 3, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koçoğlu, K.; Hodgson, T.L.; Boz, H.E.; Akdal, G. Deficits in saccadic eye movements differ between subtypes of patients with mild cognitive impairment. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2021, 43, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilcockson, T.D.; Mardanbegi, D.; Xia, B.; Taylor, S.; Sawyer, P.; Gellersen, H.W.; Leroi, I.; Killick, R.; Crawford, T.J. Abnormalities of saccadic eye movements in dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Aging 2019, 11, 5389–5398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutton, S. Cognitive control of saccadic eye movements. Brain Cogn. 2008, 68, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoula, Z.; Yang, Q.; Vernet, M.; Orssaud, C.; Samson, M.; Dieudonné, B.; Greffard, S.; Verny, M. Preservation of automatic ocular saccades in healthy elderly: Alteration in patients with dementia with Lewy body. Psychol. Neuropsychiatr. Vieil. 2010, 8, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemos, R.; Simões, M.R.; Santiago, B.; Santana, I. The free and cued selective reminding test: Validation for mild cognitive impairment and A lzheimer’s disease. J. Neuropsychol. 2015, 9, 242–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A Brief Screening Tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, D. WAiS-iii; Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Grober, E.; Merling, A.; Heimlich, T.; Lipton, R.B. Free and cued selective reminding and selective reminding in the elderly. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 1997, 19, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, J.L.; Dubois, B.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Scheltens, P. International Work Group Criteria for the Diagnosis of Alzheimer Disease. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 97, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardanbegi, D.; Wilcockson, T.; Sawyer, P.; Gellersen, H.; Crawford, T. SaccadeMachine: Software for analyzing saccade tests (anti-saccade and pro-saccade). In Proceedings of the 11th ACM Symposium on Eye Tracking Research & Applications, Denver, CO, USA, 25–28 June 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Boxer, A.L.; Garbutt, S.; Seeley, W.W.; Jafari, A.; Heuer, H.W.; Mirsky, J.; Miller, B.L. Saccade abnormalities in au-topsy-confirmed frontotemporal lobar degeneration and Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 2012, 69, 509–517. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, L.D.; Pratt, J.; Levine, B.; Black, S.E. Executive deficits detected in mild Alzheimer’s disease using the antisaccade task. Brain Behav. 2012, 2, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.; Squire, R.F.; Merrikhi, Y.; Noudoost, B. Visual attention: Linking prefrontal sources to neuronal and behavioral correlates. Prog. Neurobiol. 2015, 132, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, P.A. Impairments of attention in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 29, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinoff, E.J.; Li, K.Z.; Murtha, S.; Chertkow, H. Selective attention impairments in Alzheimer’s disease: Evidence for dissociable components. Neuropsychology 2004, 18, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Liao, Z.; Mao, Y.; Hu, J.; Le, D.; Pei, Y.; Yu, E. Temporal dynamic changes of intrinsic brain activity in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment patients: A resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxer, A.L.; Garbutt, S.; Rankin, K.P.; Hellmuth, J.; Neuhaus, J.; Miller, B.L.; Lisberger, S.G. Medial Versus Lateral Frontal Lobe Contributions to Voluntary Saccade Control as Revealed by the Study of Patients with Frontal Lobe Degeneration. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 6354–6363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbutt, S.; Matlin, A.; Hellmuth, J.; Schenk, A.K.; Johnson, J.K.; Rosen, H.; Dean, D.; Kramer, J.; Neuhaus, J.; Miller, B.L.; et al. Oculomotor function in frontotemporal lobar degeneration, related disorders and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2008, 131, 1268–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Alzheimer’s Disease (n = 65) | aMCI (n = 42) | naMCI (n = 46) | Healthy Older Controls (n = 98) | Post Hoc Contracts (p Values) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Effects | ||||||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | AD vs. OC | AD vs. aMCI | AD vs. naMCI | aMCI vs. naMCI | aMCI vs. OC | naMCI vs. OC | |

| MoCA | 19.98 | 5.71 | 20.93 | 4.46 | 25.34 | 2.17 | 28.02 | 1.79 | <0.001 * | 0.577 | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | <0.001 * |

| Digit Span | 15.64 | 4.12 | 16.35 | 3.66 | 16.66 | 4.79 | 18.72 | 4.48 | <0.001 * | 0.850 | 0.631 | 0.988 | 0.023 * | 0.050 |

| Spatial Span | 11.34 | 3.12 | 12.58 | 3.10 | 13.00 | 2.55 | 14.56 | 2.81 | <0.001 * | 0.178 | 0.022 * | 0.919 | 0.004 * | 0.021 * |

| FCSR-IC | 36.48 | 14.72 | 45.10 | 4.41 | 47.39 | 1.29 | 47.73 | 0.94 | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | 0.592 | 0.401 | 0.996 |

| Alzheimer’s Disease (n = 31) | aMCI (n = 29) | naMCI (n = 27) | Healthy Older Controls (n = 71) | Post Hoc Contracts (p Values) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Effects | ||||||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | AD vs. OC | AD vs. aMCI | AD vs. naMCI | aMCI vs. naMCI | aMCI vs. OC | naMCI vs. OC | |

| Mean Latencies | 215 | 31.88 | 201 | 39.14 | 226 | 60.33 | 203 | 48.56 | 0.648 | 0.770 | 0.826 | 0.351 | 0.997 | 0.163 |

| Coefficient of Variation | 23.14 | 10.03 | 26.93 | 17.09 | 25.57 | 15.62 | 19.77 | 12.41 | 0.627 | 0.687 | 0.916 | 0.720 | 0.060 | 0.271 |

| Alzheimer’s Disease (n = 43) | aMCI (n = 29) | naMCI (n = 27) | Healthy Older Controls (n = 69) | Post Hoc Contracts (p Values) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Effects | ||||||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | AD vs. OC | AD vs. aMCI | AD vs. naMCI | aMCI vs. naMCI | aMCI vs. OC | naMCI vs. OC | |

| Mean Latencies | 274 | 57.61 | 234 | 62.45 | 273 | 74.51 | 254 | 71.51 | 0.462 | 0.070 | 0.999 | 0.127 | 0.509 | 0.601 |

| Coefficient of Variation | 37.94 | 19.29 | 38.96 | 18.20 | 36.44 | 19.04 | 34.93 | 18.15 | 0.857 | 0.997 | 0.989 | 0.966 | 0.814 | 0.986 |

| Alzheimer’s Disease (n = 65) | aMCI (n = 42) | naMCI (n = 47) | Healthy Older Controls (n = 88) | Post Hoc Contracts (p Values) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Effects | ||||||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | AD vs. OC | AD vs. aMCI | AD vs. naMCI | aMCI VS naMCI | aMCI vs. OC | OC naMCI VS | |

| Mean Latencies | 404.34 | 86.34 | 418.91 | 81.70 | 363.05 | 61.61 | 338.12 | 83.91 | <0.001 * | .804 | 0.041 * | 0.008 * | <0.001 * | 0.320 |

| Coefficient of Variation | 23.57 | 10.43 | 20.55 | 5.80 | 25.04 | 6.79 | 24.74 | 10.30 | 0.858 | 0.376 | 0.854 | 0.133 | 0.080 | 0.998 |

| Alzheimer’s Disease | aMCI | naMCI | Healthy Older Controls | Post Hoc Contracts (p Values) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Effects | ||||||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | AD vs. OC | AD vs. aMCI | AD vs. naMCI | aMCI VS naMCI | aMCI vs. OC | OC naMCI VS | |

| Percentage error rate | 26.13 | 28.80 | 30.11 | 30.02 | 12.40 | 10.75 | 10.36 | 10.98 | <0.001 * | 0.773 | 0.004 * | 0.001 * | <0.001 * | 0.951 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Polden, M.; Crawford, T.J. Eye Movement Latency Coefficient of Variation as a Predictor of Cognitive Impairment: An Eye Tracking Study of Cognitive Impairment. Vision 2023, 7, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision7020038

Polden M, Crawford TJ. Eye Movement Latency Coefficient of Variation as a Predictor of Cognitive Impairment: An Eye Tracking Study of Cognitive Impairment. Vision. 2023; 7(2):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision7020038

Chicago/Turabian StylePolden, Megan, and Trevor J. Crawford. 2023. "Eye Movement Latency Coefficient of Variation as a Predictor of Cognitive Impairment: An Eye Tracking Study of Cognitive Impairment" Vision 7, no. 2: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision7020038

APA StylePolden, M., & Crawford, T. J. (2023). Eye Movement Latency Coefficient of Variation as a Predictor of Cognitive Impairment: An Eye Tracking Study of Cognitive Impairment. Vision, 7(2), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision7020038