Eccentric Training Interventions and Team Sport Athletes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Participants were healthy, competitive, male team sport athletes above the recreational level (i.e., professional, national, elite) and were between 17 and 35 years of age.

- The sports included in the review following the screening process were basketball, soccer, handball, and rugby union.

- Studies investigated the effects of longitudinal (≥three weeks) EO training interventions. Eccentric training load (volume, intensity) needed to be quantified.

- Data on at least one of the following outcome measures were reported: strength (e.g., 1RM, maximal voluntary contraction, peak torque), maximum sprint times (e.g., 10 m, 20 m, 40 m sprint), power (e.g., jump height, rate of force development), and change of direction (e.g., T-test, cutting).

- Participants were individual sport athletes (i.e., skiing, cycling, running) or untrained (students or with less than six months training experience). Studies not listing the training experience/sport status of participants were also excluded.

- Studies investigating male and female athletes were excluded if the results were not reported separately.

- The training intervention included injured participants.

- Supplements or ergogenic aids were used in the intervention.

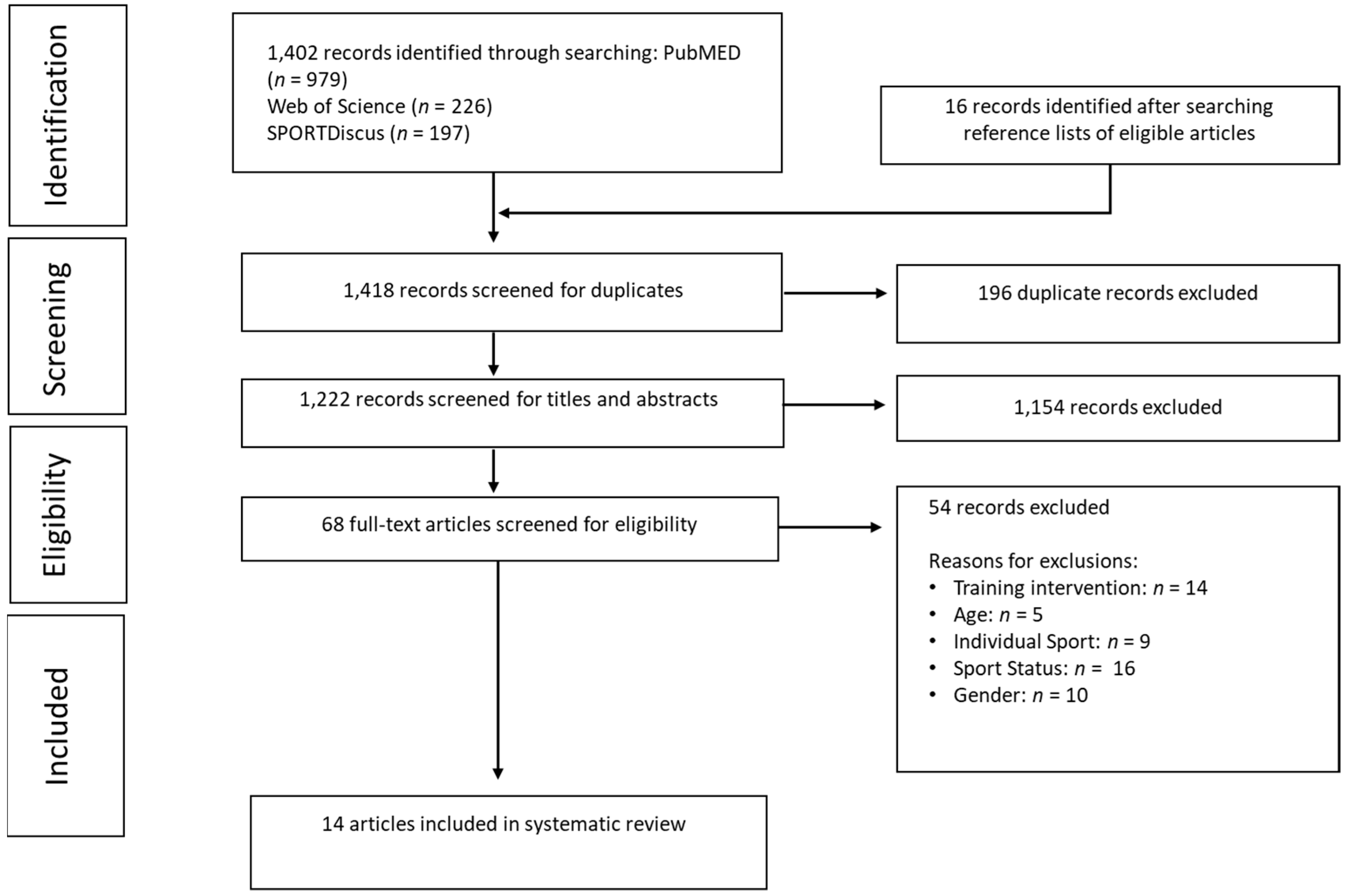

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Analysis of Results

- Inclusion criteria were clearly stated;

- Subjects were randomly allocated to groups;

- Intervention was clearly defined;

- Groups were tested for similarity at baseline;

- Use of a control group;

- Outcome variables were clearly defined;

- Assessments were practically useful;

- Duration of intervention was practically useful;

- Between-group statistical analysis was appropriate;

- Point measures of variability.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Intervention Characteristics

3.3. Outcome Measures

3.3.1. Strength

3.3.2. Speed

3.3.3. Power

3.3.4. Change of Direction

4. Discussion

4.1. Strength

4.2. Speed

4.3. Power

4.4. Change of Direction

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Douglas, J.; Pearson, S.; Ross, A.; McGuigan, M. Chronic adaptations to eccentric training: A systematic review. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 917–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindstedt, S.L.; LaStayo, P.C.; Reich, T.E. When active muscles lengthen: Properties and consequences of eccentric contractions. News Physiol. Sci. 2001, 16, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komi, P.V. Stretch-shortening cycle: A powerful model to study normal and fatigued muscle. J. Biomech. 2000, 33, 1197–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.M.; Flanagan, E.P. The role of elastic energy in activities with high force and power requirements: A brief review. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2008, 22, 1705–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cormie, P.; McGuigan, M.R.; Newton, R.U. Developing maximal neuromuscular power: Part 1—Biological basis of maximal power production. Sports Med. 2011, 41, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isner-Horobeti, M.-E.; Dufour, S.P.; Vautravers, P.; Geny, B.; Coudeyre, E.; Richard, R. Eccentric exercise training: Modalities, applications and perspectives. Sports Med. 2013, 43, 483–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilhem, G.; Cornu, C.; Guével, A. Neuromuscular and muscle-tendon system adaptations to isotonic and isokinetic eccentric exercise. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2010, 53, 319–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagle, J.P.; Taber, C.B.; Cunanan, A.J.; Bingham, G.E.; Carroll, K.M.; DeWeese, B.H.; Sato, K.; Stone, M.H. Accentuated eccentric loading for training and performance: A review. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 2473–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaabene, H.; Prieske, O.; Negra, Y.; Granacher, U. Change of direction speed: Toward a strength training approach with accentuated eccentric muscle actions. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 1773–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, M.; Hoppeler, H.H. Eccentric exercise: Mechanisms and effects when used as training regime or training adjunct. J. Appl. Physiol. 2014, 116, 1446–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B.J.; Ogborn, D.I.; Vigotsky, A.D.; Franchi, M.V.; Krieger, J.W. Hypertrophic effects of concentric vs. eccentric muscle actions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 2599–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, J.; Pearson, S.; Ross, A.; McGuigan, M. Eccentric exercise: Physiological characteristics and acute responses. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brughelli, M.; Cronin, J.; Levin, G.; Chaouachi, A. Understanding change of direction ability in sport. Sports Med. 2008, 38, 1045–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroto-Izquierdo, S.; García-López, D.; Fernandez-Gonzalo, R.; Moreira, O.C.; González-Gallego, J.; de Paz, J.A. Skeletal muscle functional and structural adaptations after eccentric overload flywheel resistance training: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2017, 20, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roig, M.; O’Brien, K.; Kirk, G.; Murray, R.; McKinnon, P.; Shadgan, B.; Reid, W.D. The effects of eccentric versus concentric resistance training on muscle strength and mass in healthy adults: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2009, 43, 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, W.G.; Marshall, S.W.; Batterham, A.M.; Hanin, J. Progressive statistics for studies in sports medicine and exercise science. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mjølsnes, R.; Arnason, A.; Østhagen, T.; Raastad, T.; Bahr, R. A 10-week randomized trial comparing eccentric vs. concentric hamstring strength training in well-trained soccer players. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2004, 14, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hoyo, M.; Pozzo, M.; Sañudo, B.; Carrasco, L.; Gonzalo-Skok, O.; Domínguez-Cobo, S.; Morán-Camacho, E. Effects of a 10-Week in-season eccentric-overload training program on muscle-injury prevention and performance in junior elite soccer players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2015, 10, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hoyo, M.; Sañudo, B.; Carrasco, L.; Mateo-Cortes, J.; Domínguez-Cobo, S.; Fernandes, O.; Del Ojo, J.J.; Gonzalo-Skok, O. Effects of 10-week eccentric overload training on kinetic parameters during change of direction in football players. J. Sports Sci. 2016, 34, 1380–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishøi, L.; Hölmich, P.; Aagaard, P.; Thorborg, K.; Bandholm, T.; Serner, A. Effects of the nordic hamstring exercise on sprint capacity in male football players: A randomized controlled trial. J. Sports Sci. 2018, 36, 1663–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Arrones, L. In-season eccentric-overload training in elite soccer players: Effects on body composition, strength and sprint performance. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askling, C.; Karlsson, J.; Thorstensson, A. Hamstring injury occurrence in elite soccer players after preseason strength training with eccentric overload. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2003, 13, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iga, J.; Fruer, C.; Deighan, M.; Croix, M.D.; James, D.V. ‘Nordic’ hamstrings exercise—Engagement characteristics and training responses. Int. J. Sports Med. 2012, 33, 1000–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krommes, K.; Petersen, J.; Nielsen, M.B.; Aagaard, P.; Hölmich, P.; Thorborg, K. Sprint and jump performance in elite male soccer players following a 10-week nordic hamstring exercise protocol: A randomised pilot study. BMC Res. Notes 2017, 10, 669. [Google Scholar]

- Maroto-Izquierdo, S.; García-López, D.; de Paz, J.A. Functional and muscle-size effects of flywheel resistance training with eccentric-overload in professional handball players. J. Hum. Kinet. 2017, 60, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabido, R.; Hernández-Davó, J.L.; Botella, J.; Navarro, A.; Tous-Fajardo, J. Effects of adding a weekly eccentric-overload training session on strength and athletic performance in team-handball players. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2017, 17, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brughelli, M.; Mendiguchia, J.; Nosaka, K.; Idoate, F.; Arcos, A.L.; Cronin, J. Effects of eccentric exercise on optimum length of the knee flexors and extensors during the preseason in professional soccer players. Phys. Ther. Sport 2010, 11, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, C.J.; Beaven, C.M.; Kilduff, L.P. Three weeks of eccentric training combined with overspeed exercises enhances power and running speed performance gains in trained athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 1280–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendiguchia, J.; Martinez-Ruiz, E.; Morin, J.B.; Samozino, P.; Edouard, P.; Alcaraz, P.E.; Esparza-Ros, F.; Mendez-Villanueva, A. Effects of hamstring-emphasized neuromuscular training on strength and sprinting mechanics in football players: Hamstring training and performance. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2015, 25, e621–e629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, E.; Paz-Domínguez, Á.; Porcel-Almendral, D.; Paredes-Hernández, V.; Barcala-Furelos, R.; Abelairas-Gómez, C. Effects of a 10-week nordic hamstring exercise and russian belt training on posterior lower-limb muscle strength in elite junior soccer players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Sanchez, J.; Gonzalo-Skok, O.; Carretero, M.; Pineda, A.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Nakamura, F.Y. Effects of concurrent eccentric overload and high-intensity interval training on team sports players’ performance. Kinesiol. Int. J. Fundam. Appl. Kinesiol. 2019, 51, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toigo, M.; Boutellier, U. New fundamental resistance exercise determinants of molecular and cellular muscle adaptations. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006, 97, 643–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tous-Fajardo, J.; Maldonado, R.A.; Quintana, J.M.; Pozzo, M.; Tesch, P.A. The flywheel leg-curl machine: Offering eccentric overload for hamstring development. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2006, 1, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann-Bette, B.; Bauer, T.; Kinscherf, R.; Vorwald, S.; Klute, K.; Bischoff, D.; Müller, H.; Weber, M.-A.; Metz, J.; Kauczor, H.-U.; et al. Effects of strength training with eccentric overload on muscle adaptation in male athletes. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 108, 821–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helland, C.; Hole, E.; Iversen, E.; Olsson, M.C.; Seynnes, O.; Solberg, P.A.; Paulsen, G. Training strategies to improve muscle power: Is olympic-style weightlifting relevant? Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, F.J.; Santalla, A.; Carrasquila, I.; Asian, J.A.; Reina, J.I.; Suarez-Arrones, L.J. The effects of unilateral and bilateral eccentric overload training on hypertrophy, muscle power and COD performance, and its determinants, in team sport players. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikne, H.; Refsnes, P.E.; Ekmark, M.; Medbø, J.I.; Gundersen, V.; Gundersen, K. Muscular performance after concentric and eccentric exercise in trained men. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2006, 38, 1770–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, K.L.; Loehr, J.A.; Lee, S.M.C.; Smith, S.M. Early-phase musculoskeletal adaptations to different levels of eccentric resistance after 8 weeks of lower body training. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2014, 114, 2263–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farthing, J.P.; Chilibeck, P.D. The effects of eccentric and concentric training at different velocities on muscle hypertrophy. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003, 89, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaven, C.M.; Willis, S.J.; Cook, C.J.; Holmberg, H.-C. Physiological comparison of concentric and eccentric arm cycling in males and females. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meylan, C.; Cronin, J.; Nosaka, K. Isoinertial assessment of eccentric muscular strength. Strength Cond. 2008, 30, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paddon-Jones, D.; Leveritt, M.; Lonergan, A.; Abernethy, P. Adaptation to chronic eccentric exercise in humans: The influence of contraction velocity. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001, 85, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buskard, A.N.L.; Gregg, H.R.; Ahn, S. Supramaximal eccentrics versus traditional loading in improving lower-body 1RM: A meta-analysis. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2018, 89, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditroilo, M.; De Vito, G.; Delahunt, E. Kinematic and electromyographic analysis of the Nordic hamstring exercise. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2013, 23, 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaraz, P.E.; Carlos-Vivas, J.; Oponjuru, B.O.; Martínez-Rodríguez, A. The effectiveness of resisted sled training (RST) for sprint performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 2143–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Lieres und Wilkau, H.C.; Irwin, G.; Bezodis, N.E.; Simpson, S.; Bezodis, I.N. Phase analysis in maximal sprinting: An investigation of step-to-step technical changes between the initial acceleration, transition and maximal velocity phases. Sports Biomech. 2018, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brughelli, M.; Cronin, J. Influence of running velocity on vertical, leg and joint stiffness: Modelling and recommendations for future research. Sports Med. 2008, 38, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, C.T.; González, O. Leg stiffness and stride frequency in human running. J. Biomech. 1996, 29, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Mangini, F.; Fábrica, G. Mechanical stiffness: A global parameter associated to elite sprinters performance. Rev. Bras. Ciências Esporte 2016, 38, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Voigt, M.; Bojsen-Møller, F.; Simonsen, E.B.; Dyhre-Poulsen, P. The influence of tendon Youngs modulus, dimensions and instantaneous moment arms on the efficiency of human movement. J. Biomech. 1995, 28, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malliaras, P.; Kamal, B.; Nowell, A.; Farley, T.; Dhamu, H.; Simpson, V.; Morrissey, D.; Langberg, H.; Maffulli, N.; Reeves, N.D. Patellar tendon adaptation in relation to load-intensity and contraction type. J. Biomech. 2013, 46, 1893–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chen, C.-S.; Ho, W.-H.; Füle, R.J.; Chung, P.-H.; Shiang, T.-Y. The effects of passive leg press training on jumping performance, speed, and muscle power. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 1479–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mike, J.N.; Cole, N.; Herrera, C.; VanDusseldorp, T.; Kravitz, L.; Kerksick, C.M. The effects of eccentric contraction duration on muscle strength, power production, vertical jump, and soreness. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, C.; Theodosiou, K.; Bogdanis, G.C.; Gkantiraga, E.; Gissis, I.; Sambanis, M.; Souglis, A.; Sotiropoulos, A. Multiarticular isokinetic high-load eccentric training induces large increases in eccentric and concentric strength and jumping performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 2680–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalo-Skok, O.; Tous-Fajardo, J.; Valero-Campo, C.; Berzosa, C.; Bataller, A.V.; Arjol-Serrano, J.L.; Moras, G.; Mendez-Villanueva, A. Eccentric-overload training in team-sport functional performance: Constant bilateral vertical versus variable unilateral multidirectional movements. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2017, 12, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.S.; Corvino, R.B.; Caputo, F.; Aagaard, P.; Denadai, B.S. Effects of fast-velocity eccentric resistance training on early and late rate of force development. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2016, 16, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormie, P.; McGuigan, M.R.; Newton, R.U. Changes in the eccentric phase contribute to improved stretch-shorten cycle performance after training. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010, 42, 1731–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcguigan, M.R.; Doyle, T.L.A.; Newton, M.; Edwards, D.J.; Nimphius, S.; Newton, R.U. Eccentric utilzation ratio: Effect of sport and phase of training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2006, 20, 992–995. [Google Scholar]

- Di Giminiani, R.; Petricola, S. The power output-drop height relationship to determine the optimal dropping intensity and to monitor the training intervention. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgeman, L.A.; McGuigan, M.R.; Gill, N.D.; Dulson, D.K. Relationships between concentric and eccentric strength and countermovement jump performance in resistance trained men. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffaye, G.; Wagner, P. Eccentric rate of force development determines jumping performance. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2013, 16, 82–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepstone, T.N.; Tang, J.E.; Dallaire, S.; Schuenke, M.D.; Staron, R.S.; Phillips, S.M. Short-term high- vs. low-velocity isokinetic lengthening training results in greater hypertrophy of the elbow flexors in young men. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 98, 1768–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, K.; Keiner, M.; Szilvas, E.; Hartmann, H.; Sander, A. Effects of eccentric strength training on different maximal strength and speed-strength parameters of the lower extremity. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 1837–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboodarda, S.J.; Page, P.A.; Behm, D.G. Eccentric and concentric jumping performance during augmented jumps with elastic resistance: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2015, 10, 839. [Google Scholar]

- Bobbert, M.F.; Huijing, P.A.; van Ingen Schenau, G.J. Drop jumping. I. The influence of jumping technique on the biomechanics of jumping. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1987, 19, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, C.H.; McDermott, W.J.; Elmer, S.J.; Martin, J.C. Chronic eccentric cycling improves quadriceps muscle structure and maximum cycling power. Int. J. Sports Med. 2014, 35, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, J.P.; Docherty, D. The effects of accentuated eccentric loading on strength, muscle hypertrophy, and neural adaptations in trained individuals. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2002, 16, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Spiteri, T.; Nimphius, S.; Hart, N.H.; Specos, C.; Sheppard, J.M.; Newton, R.U. Contribution of strength characteristics to change of direction and agility performance in female basketball athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 2415–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiteri, T.; Newton, R.U.; Binetti, M.; Hart, N.H.; Sheppard, J.M.; Nimphius, S. Mechanical determinants of faster change of direction and agility performance in female basketball athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 2205–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tous-Fajardo, J.; Gonzalo-Skok, O.; Arjol-Serrano, J.L.; Tesch, P. Enhancing change-of-direction speed in soccer players by functional inertial eccentric overload and vibration training. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2016, 11, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Inclusion Criteria | Random Allocation | Intervention Defined | Groups Tested for Similarity at Baseline | Control Group | Outcome Variables Defined | Assessments Practically Useful | Duration of Intervention Practically Useful | Between-Group Stats Analysis Appropriate | Point Measures of Variability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Askling et al. (2003) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Brughelli et al. (2010) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Cook et al. (2013) | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| de Hoyo et al. (2015) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| de Hoyo et al. (2016) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Iga et al. (2012) | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Ishøi et al. (2018) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Krommes et al. (2017) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Maroto-Izquierdo et al. (2017) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Mendiguchia et al. (2015) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Mjølsnes et al. (2004) | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Sabido et al. (2017) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Suarez-Arrones et al. (2018) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Sanchez-Sanchez et al. (2019) | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Study (Year) | Sample Size | Population | Age (Years) | Height (m) | Body Mass (kg) | Sport | Quality Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Askling et al. (2003) | Exp = 15 | Swedish Premier league | 24.0 ± 2.6 | 1.82 ± 0.06 | 78.0 ± 5.0 | Soccer | 19 |

| Con = 15 | 26.0 ± 3.6 | 1.81 ± 0.07 | 77.0 ± 6.0 | ||||

| Brughelli et al. (2010) | Exp =13 | Division 2 Spanish soccer | 20.7 ± 1.6 | 1.80 ± 0.07 | 73.1 ± 6.0 | Soccer | 16 |

| Con = 11 | 21.5 ± 1.3 | 1.79 ± 0.07 | 72.5 ± 7.5 | ||||

| Cook et al. (2013) | Exp = 5 | Semiprofessional rugby union | 19.4 ± 0.5 | 1.85 ± 0.03 | 93.8 ± 7.0 | Rugby Union | 16 |

| Exp = 5 | 19.8 ± 0.8 | 1.87 ± 0.05 | 96.6 ± 9.3 | ||||

| Exp = 5 | 19.6 ± 0.9 | 1.85 ± 0.04 | 95.8 ± 7.7 | ||||

| Exp = 5 | 19.8 ± 0.4 | 1.83 ± 0.05 | 92.8 ± 6.0 | ||||

| de Hoyo et al. (2015) | Exp = 18 | Division 1 Spanish academy soccer | 18.0 ± 1.0 | 1.78 ± 0.03 | 70.9 ± 3.9 | Soccer | 16 |

| Con = 15 | 17.0 ± 1.0 | 1.78 ± 0.01 | 73.1 ± 2.6 | ||||

| de Hoyo et al. (2016) | Exp = 17 | Division 1 Spanish academy soccer | 17.0 ± 1.0 | 1.78 ± 0.02 | 71.4 ± 3.9 | Soccer | 14 |

| Con = 14 | |||||||

| Iga et al. (2012) | Exp = 10 | English Professional League | 23.4 ± 3.3 | 1.77 ± 0.07 | 78.0 ± 8.2 | Soccer | 17 |

| Con = 8 | 22.3 ± 3.9 | 1.85 ± 0.09 | 78.0 ± 11.1 | ||||

| Ishøi et al. (2018) | Exp = 11 | Division 4 Danish academy soccer | 19.1 ± 1.8 | 1.81 ± 0.07 | 76.2 ± 11.9 | Soccer | 17 |

| Con = 14 | 19.4 ± 2.1 | 1.81 ± 0.07 | 77.0 ± 8.7 | ||||

| Krommes et al. (2017) | Exp = 9 | Division 1 Danish professional soccer | 23.0 ± 3.9 | 1.83 ± 0.05 | 73.1 ± 5.8 | Soccer | 16 |

| Con = 10 | 25.1 ± 4.9 | 1.81 ± 0.07 | 77.9 ± 9.9 | ||||

| Maroto-Izquierdo et al. (2017) | Exp = 15 | Division 1 professional handball | 19.8 ± 1.0 | 1.86 ± 0.08 | 82.3 ± 3.3 | Handball | 17 |

| Con = 14 | 23.8 ± 1.6 | 1.84 ± 0.01 | 85.6 ± 3.7 | ||||

| Mendiguchia et al. (2015) | Exp = 27 | Semiprofessional Spanish soccer | 22.7 ± 4.8 | 1.75 ± 0.06 | 71.6 ± 8.7 | Soccer | 18 |

| Con = 24 | 21.8 ± 2.5 | 1.77 ± 0.06 | 71.0 ± 7.7 | ||||

| Mjølsnes et al. (2004) | Exp = 11 | Division 1–4 Danish soccer | Soccer | 14 | |||

| Exp = 9 | |||||||

| Sabido et al. (2017) | Exp = 11 | Division 1 handball | 23.9 ± 3.8 | 1.83 ± 0.07 | 79.5 ± 7.7 | Handball | 16 |

| Con = 10 | |||||||

| Sanchez-Sanchez et al. (2019) | Exp = 12 | Regional | 22.5 ± 2.2 | 1.76 ± 0.07 | 72.6 ± 9.1 | Soccer/Basketball | 16 |

| Con = 10 | |||||||

| Suarez-Arrones et al. (2018) | Exp = 14 | Serie A Professional | 17.5 ± 0.8 | 1.80 ± 0.06 | 70.6 ± 5.3 | Soccer | 12 |

| Study (Year) | Weeks | Sessions | Sets × Reps | Equipment | Intensity | Prescription Method | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Askling et al. (2003) | 10 | 16 | 4 × 8 | Flywheel | 60° s−1 or 1.5 s | “Max Effort” | EKFPT (28, 18.9%, g = 1.06); CKFPT (20, 15.3, g = 0.81) |

| Brughelli et al. (2010) | 4 | 12 | 4–5 × ? | Bodyweight | n/a | “Max Effort” | CKFPT (−4, −2%, g = −0.17); CKEPT (6, 2.1%, g = 0.17) |

| Cook et al. (2013) | 3 | 12 | 4 × 5 | Isoinertial | 80–120% 1RM | %1RM | Bench1RM (g = 1.22); Squat1RM (g = 0.9) |

| Iga et al. (2012) | 4 | 9 | 2–3 × 5–8 | Bodyweight | 30° s−1 or 1 s | “Max Effort” | EKFPT (9 to 20, 7.4% to 20.2%, g = 0.19 to 0.54) |

| Ishøi et al. (2018) | 10 | 12 | 2–3 × 5–12 | Bodyweight | n/a | “Max Effort” | EKFPT (61.7, 19.2%, g = 0.94) |

| Maroto-Izquierdo et al. (2017) | 6 | 15 | 4 × 7 | Flywheel | Two 6.5 kg flywheels with moment inertia of 0.145 kg·m2 | “Max Effort” | LegPress1RM (31.6, 12.2%, g = 0.69) |

| Mendiguchia et al. (2015) | 7 | 14 | 1–3 × 2–8 | Isoinertial + Bodyweight | 5–15 kg or 10–70% BW | Absolute Load + % Bodyweight | CKFPT (16.3 to 18.4, −12.1% to 13.1, g = 0.67 to 0.70); EKFPT (31.3 to 42.3, 13.2% to 17.2%, g = 0.68 to 0.96) |

| Mjølsnes et al. (2004) | 10 | 12 | 2–3 × 5–12 | Bodyweight | n/a | “Max Effort” | EKFPT (27, 11.3%, g = 0.60) |

| Sabido et al. (2017) | 7 | 7 | 2–4 × 8 | Flywheel | Flywheel disc with inertia moment of 0.05 kg m2 | “Max Effort” | HalfSquat1RM (16.5, 14.2%, g = 1.67) |

| Study (Year) | Weeks | Sessions | Sets × Reps | Equipment | ECC Load/Intensity | Prescription Method | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Askling et al. (2003) | 10 | 16 | 4 × 8 | Flywheel | 60° s−1 or 1.5 s | “Max Effort” | F30 m (−0.08, −2.4%, g = 0.73) |

| Cook et al. (2013) | 3 | 12 | 4 × 5 | Isoinertial | 80–120% 1RM | %1RM | Eccentric + Overspeed vs. Traditional 40 m (0.01, g = 1.06) |

| de Hoyo et al. (2015) | 10 | 18 | 3–6 × 6 | Flywheel | Concentric = optimal power output (per inertia = 0.11 kg/m2) | “Max Effort” | 10 m (−0.02, 1%, g = 0.18); F10 m (−0.04, 3.3%, g = 0.84); 20 m (−0.04, 1.5%, g = 0.30) |

| Ishøi et al. (2018) | 10 | 12 | 2–3 × 5–12 | Bodyweight | n/a | “Max Effort” | 10 m (−0.04, 2.6%, g = 0.54) |

| Krommes et al. (2017) | 10 | 12 | 2–3 × 5–12 | Bodyweight | n/a | “Max Effort” | 5 m (−0.09, −10%, g = 0.81); 10 m (−0.10, −6%, g = 0.64); 30 m (0.10, 2.4%, g = −0.60) |

| Maroto-Izquierdo et al. (2017) | 6 | 15 | 4 × 7 | Flywheel | Two 6.5 kg flywheels with moment inertia of 0.145 kg·m2 | “Max Effort” | 20 m (−0.40, −10.8%, g = 0.98) |

| Mendiguchia et al. (2015) | 7 | 14 | 1–3 × 2–8 | Isoinertial + Bodyweight | 5–15 kg or 10–70% BW | Absolute Load + % Bodyweight | v5 m (0.20, 1.0%, g = 0.20); v20 m (−0.1, −0.4%, g = −0.08); TS (−0.1, −0.3%, g = −0.08) |

| Sabido et al. (2017) | 7 | 7 | 2–4 × 8 | Flywheel | Flywheel disc with inertia moment of 0.05 kg m2 | “Max Effort” | 20 m (−0.08, −2.5%, g = 0.82) |

| Suarez-Arrones et al. (2018) | 27 | 54 | 1–2 × 5–10 | Inertial + Bodyweight | Inertia 0.05 kg/m2 | Highest power output between two loads during familiarization | 10 m (g = 0.41); 30 m (g = 0.38); 40 m (g = 0.31) |

| Study (Year) | Weeks | Sessions | Sets × Reps | Equipment | ECC Load/Intensity | Prescription Method | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cook et al. (2013) | 3 | 12 | 4 × 5 | Isoinertial | 80–120% 1RM | %1RM | Eccentric + Overspeed CMJPP (g = 1.22) |

| de Hoyo et al. (2015) | 10 | 18 | 3–6 × 6 | Flywheel | Concentric = optimal power output (per inertia = 0.11 kg/m2) | “Max Effort” | CMJ (2.6, 7.3%, g = 0.60) |

| Krommes et al. (2017) | 10 | 12 | 2–3 × 5–12 | Bodyweight | n/a | “Max Effort” | CMJ (1.15, 2.6%, g = 0.27) |

| Maroto-Izquierdo et al. (2017) | 6 | 15 | 4 × 7 | Flywheel | Two 6.5 kg flywheels with moment inertia of 0.145 kg·m2 | “Max Effort” | PWR90 (167.5, 21.5%, g = 0.71); PWR80 (165.6, 19.7%, g = 0.73); PWR70 (113.6, 12.4%, g = 0.52); PWR60 (91.5, 10.0%, g = 0.41); PWR50 (167.5, 21.5%, g = 0.99); CMJ (3.5, 9.8%, g = 0.61); SJ (3.3, 9.9%, g = 0.54) |

| Sabido et al. (2017) | 7 | 7 | 2–4 × 8 | Flywheel | Flywheel disc with inertia moment of 0.05 kg·m2 | “Max Effort” | CMJ (2.4, 6.0%, g = 0.47); TJ_R (0.19, 2.9%, g = 0.29); TJ_L (0.40, 6.2%, g = 0.74) |

| Sanchez-Sanchez et al. (2019) | 5 | 10 | 2–3 × 6 | Flywheel | Iso-inertial pulley (0.27 kg/ m2) and flywheel (0.05 kg/m2) | “Max Effort” | CMJ (2.6, 7.4%, g = 0.46) |

| Suarez-Arrones et al. (2018) | 27 | 54 | 1–2 × 5–10 | Inertial + Bodyweight | Inertia 0.05 kg·m2 | Highest power output between two loads during familiarization | HalfSquat30 (g = 0.42); HalfSquat40 (g = 0.47); RLHS30 (g = 0.48); LLHS30 (g = 0.85); RLHS40 (g = 1.03); LLHS40 (g = 1.63) |

| Study (year) | Weeks | Sessions | Sets × Reps | Equipment | ECC Load/Intensity | Prescription Method | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| de Hoyo et al. (2016) | 10 | 18 | 3–6 × 6 | Flywheel | Concentric = optimal power output (per inertia = 0.11 kg/m2) | “Max Effort” | BT_crossover (0.01, 16.7%, g = 0.60); BT_sidestep (0.01, 16.7%, g = 0.95); CT_crossover (0.01, 7.1%, g = 0.48); CT_sidestep (0.03, 20.0%, g = 1.43); rB_IMP_crossover (0.16, 21.6%, g = 0.92); rB_IMP_sidestep (0.13, 13.5%, g = 0.53); rPB_crossover (7.4, 29.1%, g = 0.72); rPB_sidestep (9.0, 29.7%, g = 0.84) |

| Maroto-Izquierdo et al. (2017) | 6 | 15 | 4 × 7 | Flywheel | Two 6.5 kg flywheels with moment inertia of 0.145 kg·m2 | “Max Effort” | T-test (0.6, 6.5%, g = 1.46) |

| Sanchez-Sanchez et al. (2019) | 5 | 10 | 2–3 × 6 | Flywheel | Iso-inertial pulley (0.27 kg/ m2) and flywheel (0.05 kg/m2) | “Max Effort” | Illinois (1.0, 5.6%, g = 0.93) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McNeill, C.; Beaven, C.M.; McMaster, D.T.; Gill, N. Eccentric Training Interventions and Team Sport Athletes. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2019, 4, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk4040067

McNeill C, Beaven CM, McMaster DT, Gill N. Eccentric Training Interventions and Team Sport Athletes. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2019; 4(4):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk4040067

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcNeill, Conor, C. Martyn Beaven, Daniel T. McMaster, and Nicholas Gill. 2019. "Eccentric Training Interventions and Team Sport Athletes" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 4, no. 4: 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk4040067

APA StyleMcNeill, C., Beaven, C. M., McMaster, D. T., & Gill, N. (2019). Eccentric Training Interventions and Team Sport Athletes. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 4(4), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk4040067