Test–Retest Reliability of Balance Parameters Obtained with a Force Platform in Individuals with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Considerations

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection Procedures

2.3.1. Pulmonary Function

2.3.2. Risk of Falling

2.3.3. Cognitive Status

2.3.4. Postural Control

2.3.5. Functional Balance

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

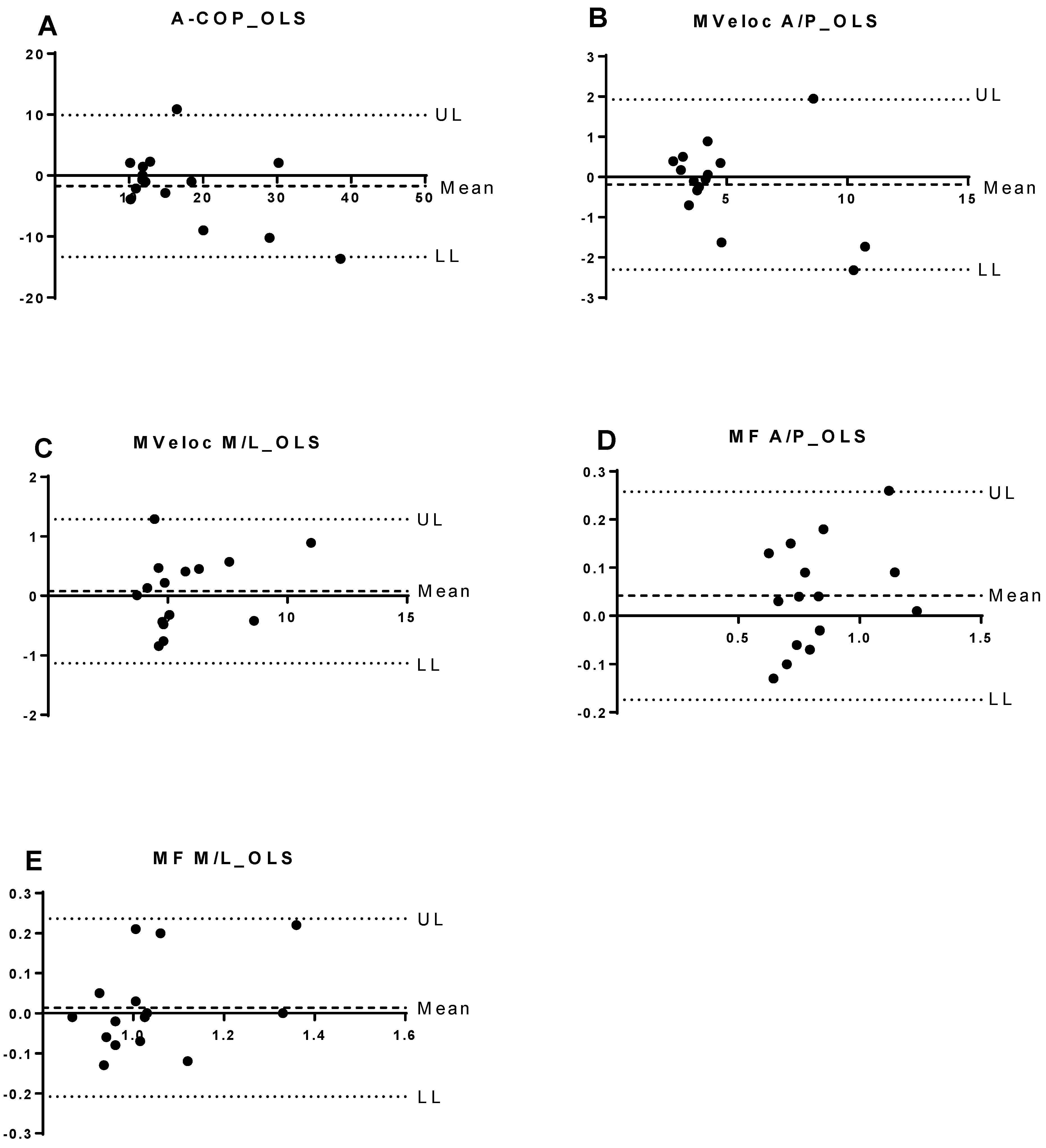

3.2. Test–Retest Reliability of Force Platform Parameters

3.3. Comparison Between Test and Retest Values

3.4. Correlation Between Balance Parameters and Functional Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GOLD 2026—Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease—GOLD. Available online: https://goldcopd.org/2026-gold-report-and-pocket-guide/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Dourado, V.Z.; Tanni, S.E.; Vale, S.A.; Faganello, M.M.; Sanchez, F.F.; Godoy, I. Manifestações sistêmicas na doença pulmonar obstrutiva crônica. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2006, 32, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roig, M.; Eng, J.J.; Road, J.D.; Reid, W.D. Falls in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A call for further research. Respir. Med. 2009, 103, 1257–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasten, J.G.; Aguayo, J.C.; Aburto, J.; Araya-Quintanilla, F.; Álvarez-Bustos, A.; Valenzuela-Fuenzalida, J.J.; Camp, P.G.; Sepúlveda-Loyola, W. Dual-Task Performance in Individuals with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Pulm. Med. 2024, 2024, 1230287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ucgun, H.; Kaya, M.; Ogun, H.; Denizoglu Kulli, H. Exploring Balance Impairment and Determinants in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Comparative Study with Healthy Subjects. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.D.; Chang, A.T.; Seale, H.E.; Walsh, J.R.; Hodges, P.W. Balance is impaired in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Gait Posture 2010, 31, 456–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porto, E.F.; Castro, A.A.M.; Schmidt, V.G.S.; Rabelo, H.M.; Kümpel, C.; Nascimento, O.A.; Jardim, J.R. Postural control in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2015, 10, 1233–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roig, M.; Eng, J.; MacIntyre, D.; Road, J.; FitzGerald, J.; Burns, J.; Reid, W. Falls in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: An observational cohort study. Respir. Med. 2011, 105, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.C.; Lee, A.L.; McGinley, J.; Thompson, M.; Irving, L.B.; Anderson, G.P.; Clark, R.A.; Clarke, S.; Denehy, L. Falls by individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A preliminary 12-month prospective cohort study. Respirology 2015, 20, 1096–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Loughlin, J.L.; Boivin, J.F.; Robitaille, Y.; Suissa, S. Falls among the elderly: Distinguishing indoor and outdoor risk factors in Canada. J. Epidemiol. Community Health (1978) 1994, 48, 488–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, T. Guideline for the prevention of falls in older persons. American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society, and American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Panel on Falls Prevention. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2001, 49, 664–672. [Google Scholar]

- Tinetti, M.E.; Speechley, M.; Ginter, S.F. Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988, 319, 1701–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, P.; Calisti, M.; Werner, I.; Debertin, D.; Mayer-Suess, L.; Knoflach, M.; Federolf, P. Validity and Reliability of the Posturographic Outcomes of a Portable Balance Board. Sensors 2025, 25, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, M.; Freitas, S.M.S.F. Revisão sobre posturografia baseada em plataforma de força para avaliação do equilíbrio. Rev. Bras. Fisioter. 2010, 14, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, D.A. Human balance and posture control during standing and walking. Gait Posture 1995, 3, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, R.A.; Bilodeau, M.; Parreira, R.B.; Teixeira, D.C.; Amorim, C.F. Age-related differences in time-limit performance and force platform-based balance measures during one-leg stance. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2013, 23, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasq, D.; Labrunée, M.; Amarantini, D.; Dupui, P.; Montoya, R.; Marque, P. Between-day reliability of centre of pressure measures for balance assessment in hemiplegic stroke patients. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2014, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Castro, L.A.; Morita, A.A.; Sepúlveda-Loyola, W.; da Silva, R.A.; Pitta, F.; Krueger, E.; Probst, V.S. Are there differences in muscular activation to maintain balance between individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and controls? Respir. Med. 2020, 173, 106016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Castro, L.A.; Felcar, J.M.; de Carvalho, D.R.; Vidotto, L.S.; da Silva, R.A.; Pitta, F.; Probst, V.S. Effects of land- and water-based exercise programmes on postural balance in individuals with COPD: Additional results from a randomised clinical trial. Physiotherapy 2020, 107, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Castro, L.A.; Ribeiro, L.R.; Mesquita, R.; De Carvalho, D.R.; Felcar, J.M.; Merli, M.F.; Fernandes, K.B.; da Silva, R.A.; Teixeira, D.C.; Spruit, M.A.; et al. Static and Functional Balance in Individuals With COPD: Comparison with Healthy Controls and Differences According to Sex and Disease Severity. Respir. Care 2016, 61, 1488–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malta, M.; Cardoso, L.O.; Bastos, F.I.; Magnanini, M.M.F.; da Silva, C.M.F.P. STROBE initiative: Guidelines on reporting observational studies. Rev. Saude Publica 2010, 44, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, S.D.; Eliasziw, M.; Donner, A. Sample size and optimal designs for reliability studies. Stat. Med. 1998, 17, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, B.L.; Steenbruggen, I.; Miller, M.R.; Barjaktarevic, I.Z.; Cooper, B.G.; Hall, G.L.; Hallstrand, T.S.; Kaminsky, D.A.; McCarthy, K.; McCormack, M.C.; et al. Standardization of spirometry: 2019 update. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, e70–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Castro Pereira, C.A.; Sato, T.; Rodrigues, S.C. New reference values for forced spirometry in white adults in Brazil. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2007, 33, 397–406. [Google Scholar]

- Downton, J.H. Falls in the Elderly; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1993; Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/FALLS_IN_THE_ELDERLY.html?hl=es&id=gx1iNAAACAAJ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Biazus, M.; Balbinot, N.; Wibelinger, L.M. Avaliação do risco de quedas em idosos. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Envelhec. Hum. 2010, 7, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolucci, P.H.F.; Brucki, S.M.D.; Campacci, S.R.; Juliano, Y. O Mini-Exame do Estado Mental em uma população geral: Impacto da escolaridade. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 1994, 52, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsiadlo, D.; Richardson, S. The timed “Up & Go”: A test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1991, 39, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, R.; Janssen, D.J.A.; Wouters, E.F.M.; Schols, J.M.G.A.; Pitta, F.; Spruit, M.A. Within-day test-retest reliability of the Timed Up & Go test in patients with advanced chronic organ failure. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013, 94, 2131–2138. [Google Scholar]

- Sepúlveda-Loyola, W.; Álvarez-Bustos, A.; Valenzuela-Fuenzalida, J.J.; Ordinola Ramírez, C.M.; Saldías Solis, C.; Probst, V.S. Are There Differences in Postural Control and Muscular Activity in Individuals with COPD and with and Without Sarcopenia? Adv. Respir. Med. 2025, 93, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil, A.W.O.; Oliveira, M.R.; Coelho, V.A.; Carvalho, C.E.; Teixeira, D.C.; da Silva, R.A. Relationship between force platform and two functional tests for measuring balance in the elderly. Rev. Bras. Fisioter. 2011, 15, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azambuja, R.; Bettencourt, M.; Costa CHda Rufino, R. Panorama da doença pulmonar obstrutiva crônica. Rev. HUPE 2013, 12, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandes, N.A.; Teixeira Dde, C.; Brunetto, V.S.P.A.F.; Ramos, E.M.C.; Pitta, F. Profile of the level of physical activity in the daily lives of patients with COPD in Brazil. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2009, 35, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | |

| n (M/F) | 20 (13/7) |

| Age (years) | 71 ± 6 |

| FEV1 (% predicted) | 50.1 ± 16 |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.58 ± 0.11 |

| GOLD classification (I/II/III/IV) | 0/11/7/2 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26 ± 5 |

| TUG (s) | 12.6 ± 3.3 |

| Number of falls in the last year | 0.35 ± 0.9 |

| Mini Mental State Examination (score) | 25.79 ± 3.61 |

| Tasks | Parameters | ICC | CI 95% | SEM | %SEM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FHEO | COP-area | 0.90 | 0.72–0.97 | 1.06 | 33 |

| Vel-AP | 0.96 | 0.90–0.99 | 0.15 | 13 | |

| Vel-ML | 0.94 | 0.80–0.98 | 0.07 | 9 | |

| Freq-AP | 0.95 | 0.87–0.98 | 0.04 | 11 | |

| Freq-ML | 0.88 | 0.68–0.96 | 0.05 | 11 | |

| FHEC | COP-area | 0.95 | 0.86–0.98 | 0.79 | 24 |

| Vel-AP | 0.95 | 0.87–0.98 | 0.15 | 11 | |

| Vel-ML | 0.92 | 0.80–0.97 | 0.15 | 18 | |

| Freq-AP | 0.96 | 0.87–0.98 | 0.06 | 17 | |

| Freq-ML | 0.90 | 0.73–0.96 | 0.04 | 7 | |

| SSB | COP-area | 0.94 | 0.84–0.98 | 1.56 | 22 |

| Vel-AP | 0.97 | 0.92–0.99 | 0.18 | 13 | |

| Vel-ML | 0.97 | 0.92–0.99 | 0.20 | 12 | |

| Freq-AP | 0.91 | 0.75–0.97 | 0.08 | 21 | |

| Freq-ML | 0.92 | 0.77–0.97 | 0.05 | 13 | |

| OLS | COP-area | 0.85 | 0.55–0.95 | 2.73 | 16 |

| Vel-AP | 0.96 | 0.87–0.99 | 0.79 | 16 | |

| Vel-ML | 0.97 | 0.92–0.99 | 0.42 | 7 | |

| Freq-AP | 0.89 | 0.66–0.96 | 0.08 | 10 | |

| Freq-ML | 0.85 | 0.55–0.95 | 0.07 | 7 |

| Tasks | Parameters | Test | Retest | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FHEO | COP-area | 2.7 [1.3–5.1] | 2.14 [1.5–4.8] | 0.49 |

| Vel-AP | 1.1 [0.9–1.3] | 1.0 [0.9–1.4] | 0.94 | |

| Vel-ML | 0.75 ± 0.18 | 0.72 ± 0.22 | 0.38 | |

| Freq-AP | 0.34 [0.2–0.4] | 0.3 [0.27–0.43] | 0.93 | |

| Freq-ML | 0.43 [0.4–0.5] | 0.45 [0.3–0.62] | 0.46 | |

| FHEC | COP-area | 2.9 [1.3–4.5] | 2.25 [1.5–4.7] | 0.65 |

| Vel-AP | 1.39 ± 0.45 | 1.42 ± 0.55 | 0.60 | |

| Vel-ML | 0.79 [0.6–1.0] | 0.71 [0.6–1.1] | 0.93 | |

| Freq-AP | 0.33 [0.3–0.4] | 0.36 [0.27–0.46] | 0.80 | |

| Freq-ML | 0.53 ± 0.16 | 0.56 ± 0.21 | 0.28 | |

| SSB | COP-area | 6.2 [4.3–7.6] | 6.83 [4.3–84] | 0.47 |

| Vel-AP | 1.24 [1.2–1.5] | 1.28 [1.1–1.9] | 0.99 | |

| Vel-ML | 1.53 [1.4–1.9] | 1.57 [1.4–2.0] | 0.77 | |

| Freq-AP | 0.33 [0.3–0.5] | 0.33 [0.24–0.5] | 0.84 | |

| Freq-ML | 0.34 [0.3–0.4] | 0.38 [0.3–0.45] | 0.52 | |

| OLS | COP-area | 13.5 [11.4–21.9] | 12.14 [11.7–24.5] | 0.32 |

| Vel-AP | 3.9 [3.4–4.9] | 3.98 [3.7–5.6] | 0.77 | |

| Vel-ML | 4.91 [4.4–6.5] | 5.06 [4.4–6.1] | 0.68 | |

| Freq-AP | 0.79 [0.7–0.9] | 0.76 [0.71–0.85] | 0.20 | |

| Freq-ML | 1.02 [0.9–1.1] | 1.0 [0.96–1.05] | 0.98 |

| Tasks | Parameters | TUG | Falls | Downton Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FHEO | COP-area | −0.009 | 0.13 | 0.45 |

| Vel-AP | 0.64 * | 0.02 | 0.68 * | |

| Vel-ML | 0.32 | 0.10 | 0.62 * | |

| Freq-AP | 0.65 * | −0.14 | 0.34 | |

| Freq-ML | 0.31 | 0.17 | 0.08 | |

| FHEC | COP-area | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.50 |

| Vel-AP | 0.80 * | −0.005 | 0.63 * | |

| Vel-ML | 0.34 | 0.04 | 0.53 * | |

| Freq- AP | 0.64 * | −0.15 | 0.35 | |

| Freq-ML | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.05 | |

| SSB | COP-area | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.51 * |

| Vel-AP | 0.72 * | −0.006 | 0.51 * | |

| Vel-ML | 0.64 * | −0.20 | 0.42 | |

| Freq-AP | 0.64 * | −0.21 | 0.30 | |

| Freq-ML | 0.60 * | −0.10 | 0.34 | |

| OLS | COP-area | 0.10 | −0.20 | 0.0002 |

| Vel-AP | 0.45 | −0.10 | 0.36 | |

| Vel-ML | −0.04 | −0.2 | 0.32 | |

| Freq-AP | 0.31 | −0.08 | 0.36 | |

| Freq-ML | 0.18 | −0.07 | 0.40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Brito, I.L.d.; Sepúlveda-Loyola, W.; Castro, L.A.d.; Ordoñez-Mora, L.T.; Silva Junior, A.J.d.; Probst, V.S. Test–Retest Reliability of Balance Parameters Obtained with a Force Platform in Individuals with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2026, 11, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010024

Brito ILd, Sepúlveda-Loyola W, Castro LAd, Ordoñez-Mora LT, Silva Junior AJd, Probst VS. Test–Retest Reliability of Balance Parameters Obtained with a Force Platform in Individuals with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2026; 11(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrito, Igor Lopes de, Walter Sepúlveda-Loyola, Larissa Araújo de Castro, Leidy Tatiana Ordoñez-Mora, Ademilson Julio da Silva Junior, and Vanessa S. Probst. 2026. "Test–Retest Reliability of Balance Parameters Obtained with a Force Platform in Individuals with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 11, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010024

APA StyleBrito, I. L. d., Sepúlveda-Loyola, W., Castro, L. A. d., Ordoñez-Mora, L. T., Silva Junior, A. J. d., & Probst, V. S. (2026). Test–Retest Reliability of Balance Parameters Obtained with a Force Platform in Individuals with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 11(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010024