Mechanical Characteristics and Skating Performance of Trained Youth Ice Hockey Players at Different Maturation Stages

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Study Design

2.2. Variables

2.2.1. Skating Performance

2.2.2. Physical Maturation

2.3. Statistical Analyses

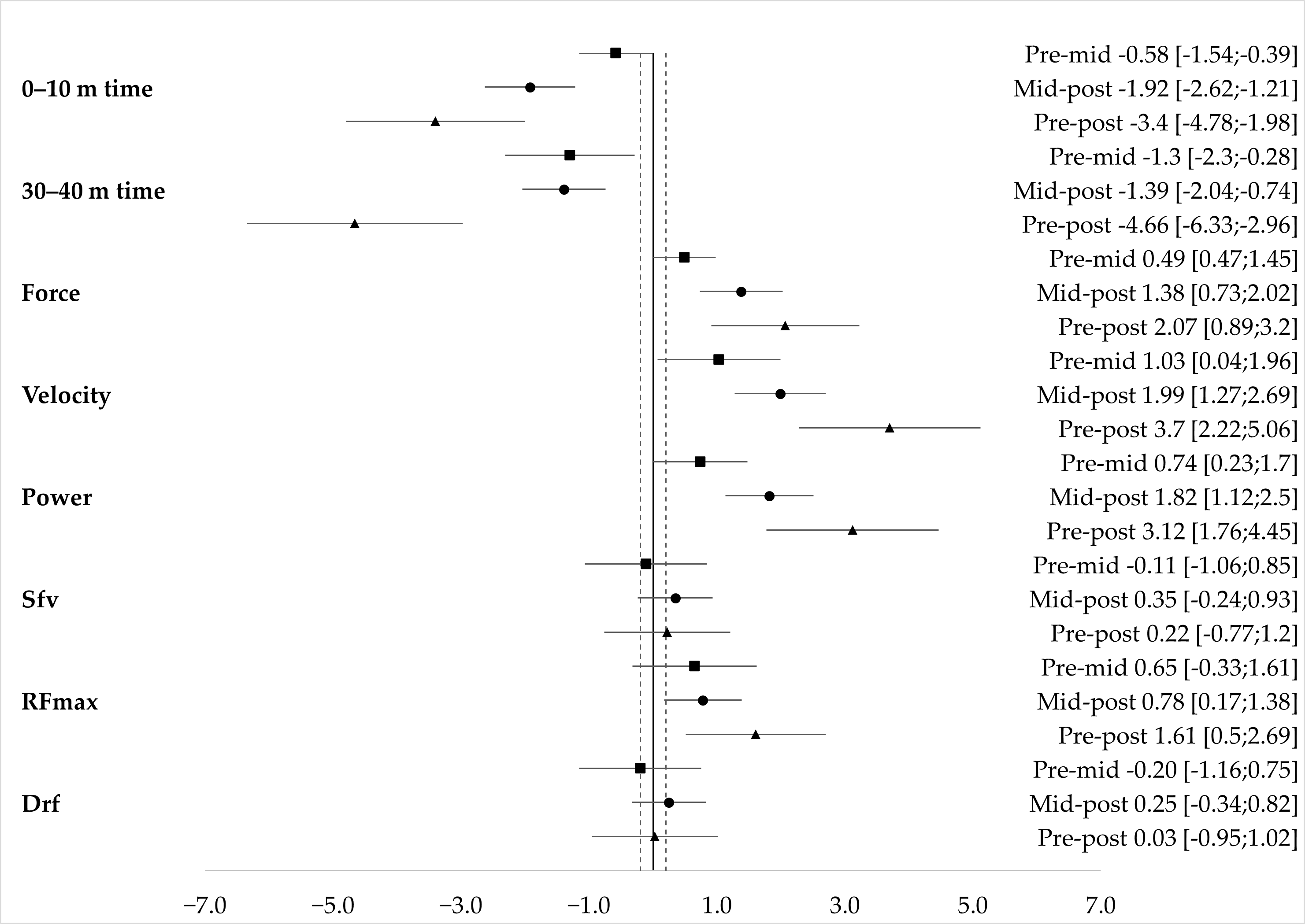

3. Results

| Pre-PHV n = 5 (10%) | Mid-PHV n = 28 (54%) | Post-PHV n = 19 (36%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 12.8 ± 0.5 [12.2, 13.4] | 14.0 ± 1.0 [13.6, 14.4] | 16.0 ± 0.7 [15.7, 16.3] |

| Stature (m) | 1.48 ± 0.09 [1.36, 1.59] | 1.69 ± 0.06 [1.66, 1.71] | 1.72 ± 0.05 [1.70, 1.74] |

| Sitting height (m) | 0.75 ± 0.05 [0.68, 0.82] | 0.84 ± 0.04 [0.82, 0.85] | 0.87 ± 0.02 [0.86, 0.88] |

| Mass (kg) | 40.6 ± 3.0 [36.9, 44.3] | 60.2 ± 9.1 [56.7, 63.7] | 72.6 ± 4.6 [70.4, 74.8] |

| Maturity offset (years) | −1.38 ± 0.37 [−1.84, −0.93] | 0.10 ± 0.58 [−0.13, 0.32] | 1.63 ± 0.37 [1.45, 1.81] |

| 0–10 m time (s) | 2.20 ± 0.09 [2.10, 2.27] | 2.11 ± 0.16 [2.05, 2.17] | 1.84 ± 0.11 [1.79, 1.89] |

| 30–40 m time (s) | 1.39 ± 0.13 [1.26, 1.48] | 1.22 ± 0.13 [1.17, 1.27] | 1.07 ± 0.05 [1.05, 1.09] |

| F0 (N·kg−1) | 4.43 ± 0.52 [4.02, 4.98] | 4.71 ± 0.56 [4.51, 4.92] | 5.44 ± 0.48 [5.22, 5.64] |

| V0 (m·s−1) | 8.60 ± 0.37 [8.32, 8.97] | 9.20 ± 0.61 [8.98, 9.42] | 10.32 ± 0.48 [10.11, 10.54] |

| Pmax (W·kg−1) | 9.53 ± 1.25 [8.50, 10.97] | 10.87 ± 1.89 [10.20, 11.60] | 14.03 ± 1.48 [13.36, 14.69] |

| Sfv (N·m·s−1) | −0.52 ± 0.06 [−0.58, −0.48] | −0.51 ± 0.05 [−0.53, −0.49] | −0.53 ± 0.05 [−0.55, −0.51] |

| RFmax (%) | 31.6 ± 4.35 [27.94, 35.81] | 34.15 ± 3.9 [32.67, 35.64] | 36.96 ± 3.06 [35.57, 38.25] |

| Drf (%) | −5.0 ± 0.56 [−5.54, −4.59] | −4.91 ± 0.4 [−5.07, −4.75] | −5.10 ± 0.43 [−5.19, −4.82] |

| F(2,49) | p | η2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–10 m time (s) | 26.61 | <0.001 | 0.52 [0.30, 0.64] |

| 30–40 m time (s) | 20.86 | <0.001 | 0.46 [0.23, 0.59] |

| F0 (N·kg−1) | 13.44 | <0.001 | 0.35 [0.13, 0.51] |

| V0 (m·s−1) | 31.72 | <0.001 | 0.56 [0.35, 0.68] |

| Pmax (W·kg−1) | 24.83 | <0.001 | 0.50 [0.28, 0.63] |

| Sfv (N·m·s−1) | 0.64 | 0.53 | 0.03 [0.00, 0.13] |

| RFmax (%) | 5.58 | 0.007 | 0.19 [0.02, 0.35] |

| Drf (%) | 0.35 | 0.71 | 0.01 [0.00, 0.10] |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| Drf | Rate of decrease in the ratio of the horizontal component of the ground reaction force |

| F–V | Force–velocity profile |

| F0 | Maximal theoretical force |

| PHV | Peak height velocity |

| Pmax | Maximal theoretical power |

| RFmax | Maximal ratio of the horizontal component of the ground reaction force |

| Sfv | Force–velocity slope |

| V0 | Maximal theoretical velocity |

References

- Brocherie, F.; Girard, O.; Millet, G.P. Updated analysis of changes in locomotor activities across periods in an international ice hockey game. Biol. Sport 2018, 35, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, A.S.; Kennedy, C.R. Tracking in-match movement demands using local positioning system in world-class men’s ice hockey. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocherie, F.; Perez, J.; Guilhem, G. Effects of a 14-Day High-Intensity Shock Microcycle in High-Level Ice Hockey Players’ Fitness. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 36, 2247–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dæhlin, T.E.; Haugen, O.C.; Haugerud, S.; Hollan, I.; Raastad, T.; Rønnestad, B.R. Improvement of ice hockey players’ on-ice sprint with combined plyometric and strength training. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2017, 12, 893–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagrange, S.; Ferland, P.-M.; Leone, M.; Comtois, A.S. Contrast training generates post-activation potentiation and improves repeated sprint ability in elite ice hockey players. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2017, 13, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, M.J.; Comfort, P.; Crebin, R. Complex training in ice hockey: The effects of a heavy resisted sprint on subsequent ice-hockey sprint performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2010, 24, 2883–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albaladejo-Saura, M.; Vaquero-Cristóbal, R.; González-Gálvez, N.; Esparza-Ros, F. Relationship between biological maturation, physical fitness, and kinanthropometric variables of young athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbs, I.J.; Oliver, J.L.; Wong, M.A.; Moore, I.S.; Lloyd, R.S. Effects of a 12-week training program on isometric and dynamic force-time characteristics in pre–and post–peak height velocity male athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Galván, L.M.; Jiménez-Reyes, P.; Cuadrado-Peñafiel, V.; Casado, A. Sprint Performance and Mechanical Force-Velocity Profile Among Different Maturational Stages in Young Soccer Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samozino, P.; Rabita, G.; Dorel, S.; Slawinski, J.; Peyrot, N.; Saez de Villarreal, E.; Morin, J.B. A simple method for measuring power, force, velocity properties, and mechanical effectiveness in sprint running. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2016, 26, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, J.-B.; Samozino, P.; Murata, M.; Cross, M.R.; Nagahara, R. A simple method for computing sprint acceleration kinetics from running velocity data: Replication study with improved design. J. Biomech. 2019, 94, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samozino, P.; Peyrot, N.; Edouard, P.; Nagahara, R.; Jimenez-Reyes, P.; Vanwanseele, B.; Morin, J.B. Optimal mechanical force-velocity profile for sprint acceleration performance. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2022, 32, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, J.; Guilhem, G.; Brocherie, F. Reliability of the force-velocity-power variables during ice hockey sprint acceleration. Sports Biomech. 2022, 21, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenroth, L.; Vartiainen, P.; Karjalainen, P.A. Force-velocity profiling in ice hockey skating: Reliability and validity of a simple, low-cost field method. Sports Biomech. 2023, 22, 874–889, Erratum in Sports Biomech. 2023, 22, X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, J.; Guilhem, G.; Hager, R.; Brocherie, F. Mechanical determinants of forward skating sprint inferred from off-and on-ice force-velocity evaluations in elite female ice hockey players. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2021, 21, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaude-Roy, J.; Pharand, P.; Brunelle, J.-F.; Lemoyne, J. Exploring associations between sprinting mechanical capabilities, anaerobic capacity, and repeated-sprint ability of adolescent ice hockey players. Front. Sports Act. Living 2023, 5, 1258497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaude-Roy, J.; Ducas, J.; Brunelle, J.F.; Lemoyne, J. Associations between skating mechanical capabilities and off-ice physical abilities of highly trained teenage ice hockey players. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2024, 24, 1414–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelletier, V.H.; Trudeau, F.; Lemoyne, J. Development of physiological, anthropometric and psychological parameters in adolescent ice hockey players. Mov. Sport Sci. Mot. 2025, 128, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budarick, A.R.; Shell, J.R.; Robbins, S.M.; Wu, T.; Renaud, P.J.; Pearsall, D.J. Ice hockey skating sprints: Run to glide mechanics of high calibre male and female athletes. Sports Biomech. 2020, 19, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, S.M.; Renaud, P.J.; Pearsall, D.J. Principal component analysis identifies differences in ice hockey skating stride between high-and low-calibre players. Sports Biomech. 2021, 20, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, A.K.; Stellingwerff, T.; Smith, E.S.; Martin, D.T.; Mujika, I.; Goosey-Tolfrey, V.L.; Sheppard, J.; Burke, L.M. Defining training and performance caliber: A participant classification framework. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2021, 17, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stastny, P.; Musalek, M.; Roczniok, R.; Cleather, D.; Novak, D.; Vagner, M. Testing distance characteristics and reference values for ice-hockey straight sprint speed and acceleration. A systematic review and meta-analyses. Biol. Sport 2023, 40, 899–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundle, M.W.; Hoyt, R.W.; Weyand, P.G. High-speed running performance: A new approach to assessment and prediction. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003, 95, 1955–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawczuk, T.; Jones, B.; Scantlebury, S.; Weakley, J.; Read, D.; Costello, N.; Darrall-Jones, J.D.; Stokes, K.; Till, K. Between-day reliability and usefulness of a fitness testing battery in youth sport athletes: Reference data for practitioners. Meas. Phys. Educ. Exerc. Sci. 2018, 22, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, T.; Banyard, H.G.; Piggott, B.; Haff, G.G.; Joyce, C. Reliability and minimal detectable change of sprint times and force-velocity-power characteristics. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36, 268–272, Erratum in J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36, e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simperingham, K.D.; Cronin, J.B.; Pearson, S.N.; Ross, A. Reliability of horizontal force–velocity–power profiling during short sprint-running accelerations using radar technology. Sports Biomech. 2019, 18, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.A.; McKay, H.A.; Macdonald, H.; Nettlefold, L.; Baxter-Jones, A.D.; Cameron, N.; Brasher, P.M. Enhancing a somatic maturity prediction model. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2015, 47, 1755–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.; Roberts, S.J.; Mckeown, J.; Littlewood, M.; McLaren-Towlson, C.; Andrew, M.; Enright, K. Methods to predict the timing and status of biological maturation in male adolescent soccer players: A narrative systematic review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, R.R. Understanding the practical advantages of modern ANOVA methods. J. Clin. Child Adol. Psychol. 2002, 31, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, W.; Marshall, S.; Batterham, A.; Hanin, J. Progressive statistics for studies in sports medicine and exercise science. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaartinen, S.; Vartiainen, P.; Venojärvi, M.; Tikkanen, H.; Stenroth, L. Kinematic and muscle activity patterns of maximal ice hockey skating acceleration. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaartinen, S.; Venojärvi, M.; Lesch, K.J.; Tikkanen, H.; Vartiainen, P.; Stenroth, L. Lower limb muscle activation patterns in ice-hockey skating and associations with skating speed. Sports Biomech. 2024, 23, 2233–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allisse, M.; Bui, H.T.; Desjardins, P.; Léger, L.; Comtois, A.S.; Leone, M. Assessment of on-ice oxygen cost of skating performance in elite youth ice hockey players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 3466–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckeridge, E.; LeVangie, M.C.; Stetter, B.; Nigg, S.R.; Nigg, B.M. An on-ice measurement approach to analyse the biomechanics of ice hockey skating. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemoyne, J.; Brunelle, J.-F.; Huard Pelletier, V.; Glaude-Roy, J.; Martini, G. Talent Identification in Elite Adolescent Ice Hockey Players: The Discriminant Capacity of Fitness Tests, Skating Performance and Psychological Characteristics. Sports 2022, 10, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, D.S.; Drummond, C.; Williams, K.J.; Pickering, C.; van den Tillaar, R. Individualization of training based on sprint force-velocity profiles: A conceptual framework for biomechanical and technical training recommendations. Strength Cond. J. 2022, 45, 711–725. [Google Scholar]

- Lemoyne, J.; Huard Pelletier, V.; Trudeau, F.; Grondin, S. Relative age effect in Canadian hockey: Prevalence, perceived competence and performance. Front. Sports Act. Living 2021, 3, 622590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grondin, S. To be or not to be born at the right time: Lessons from ice hockey. Front. Sports Act. Living 2024, 6, 1440029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobley, S.; Till, K. Longitudinal studies of athlete development: Their importance, methods and future considerations. In Routledge Handbook of Talent Identification and Development in Sport; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017; pp. 250–268. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, J.-B.; Bourdin, M.; Edouard, P.; Peyrot, N.; Samozino, P.; Lacour, J.-R. Mechanical determinants of 100-m sprint running performance. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2012, 112, 3921–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secomb, J.L.; Davidson, D.W.; Compton, H.R. Relationships between sprint skating performance and insole plantar forces in national-level hockey athletes. Gait Posture 2024, 113, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Glaude-Roy, J.; Lemoyne, J. Mechanical Characteristics and Skating Performance of Trained Youth Ice Hockey Players at Different Maturation Stages. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2026, 11, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010002

Glaude-Roy J, Lemoyne J. Mechanical Characteristics and Skating Performance of Trained Youth Ice Hockey Players at Different Maturation Stages. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2026; 11(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleGlaude-Roy, Julien, and Jean Lemoyne. 2026. "Mechanical Characteristics and Skating Performance of Trained Youth Ice Hockey Players at Different Maturation Stages" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 11, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010002

APA StyleGlaude-Roy, J., & Lemoyne, J. (2026). Mechanical Characteristics and Skating Performance of Trained Youth Ice Hockey Players at Different Maturation Stages. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 11(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010002