Differences in Total Daily Energy Expenditure Across Field Sports: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- •

- Athletic populations competing in soccer or rugby.

- •

- Studies including both male and female athletes.

- •

- Athletes across all levels of competition were considered.

- •

- Published in English.

- •

- Published across any timeframe.

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Bioenergetic Demands of Team Sports

4.2. TDEE and PAL Values Across Sports

4.3. Using TDEE and PAL to Personalize Athlete Nutrition

4.4. Future Directions and Research Needs

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| (R)TDEE | (Relative) Total Daily Energy Expenditure |

| PAL | Physical Activity Level |

| RMR | Resting Metabolic Rate |

| PAEE | Physical Activity Energy Expenditure |

| NEAT | Non–Exercise Activity Thermogenesis |

| METs | Metabolic Equivalents |

| LEA | Low Energy Availability |

| RED–S | Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport |

| DLW | Doubly Labeled Water |

References

- American Dietetic Association; Dietitians of Canada; American College of Sports Medicine; Rodriguez, N.R.; Di Marco, N.M.; Langley, S. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Nutrition and athletic performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 709–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerksick, C.M.; Wilborn, C.D.; Roberts, M.D.; Smith-Ryan, A.; Kleiner, S.M.; Jäger, R.; Collins, R.; Cooke, M.; Davis, J.N.; Galvan, E.; et al. ISSN exercise & sports nutrition review update: Research & recommendations. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2018, 15, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mountjoy, M.; Ackerman, K.E.; Bailey, D.M.; Burke, L.M.; Constantini, N.; Hackney, A.C.; Heikura, I.A.; Melin, A.; Pensgaard, A.M.; Stellingwerff, T.; et al. 2023 International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) consensus statement on Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs). Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 1073–1097, Erratum in Br. J. Sports Med. 2024, 58, e4. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2023-106994corr1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heydenreich, J.; Kayser, B.; Schutz, Y.; Melzer, K. Total Energy Expenditure, Energy Intake, and Body Composition in Endurance Athletes Across the Training Season: A Systematic Review. Sports Med.-Open 2017, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerterp, K.R. Physical activity and physical activity induced energy expenditure in humans: Measurement, determinants, and effects. Front. Physiol. 2013, 4, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, J.J. A reanalysis of the factors influencing basal metabolic rate in normal adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1980, 33, 2372–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravussin, E.; Lillioja, S.; Anderson, T.E.; Christin, L.; Bogardus, C. Determinants of 24-hour energy expenditure in man. Methods and results using a respiratory chamber. J. Clin. Investig. 1986, 78, 1568–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravussin, E.; Harper, I.T.; Rising, R.; Bogardus, C. Energy expenditure by doubly labeled water: Validation in lean and obese subjects. Am. J. Physiol. 1991, 261, E402–E409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainslie, P.; Reilly, T.; Westerterp, K. Estimating human energy expenditure: A review of techniques with particular reference to doubly labelled water. Sports Med. 2003, 33, 683–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, H.; Kawakami, R.; Nakae, S.; Nakata, Y.; Ishikawa-Takata, K.; Tanaka, S.; Miyachi, M. Accuracy of Wearable Devices for Estimating Total Energy Expenditure: Comparison With Metabolic Chamber and Doubly Labeled Water Method. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 702–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeran, S.; Steinbrecher, A.; Pischon, T. Prediction of activity-related energy expenditure using accelerometer-derived physical activity under free-living conditions: A systematic review. Int. J. Obes. 2016, 40, 1187–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainsworth, B.E.; Haskell, W.L.; Herrmann, S.D.; Meckes, N.; Bassett, D.R.J.; Tudor-Locke, C.; Greer, J.L.; Vezina, J.; Whitt-Glover, M.C.; Leon, A.S. 2011 Compendium of Physical Activities: A Second Update of Codes and MET Values. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.-S.; Chang, C.-H.; Hsu, Y.-J.; Tu, Y.-T.; Li, F.; Jhang, W.-L.; Hsu, C.-W.; Huang, C.-C. Feasibility of the Energy Expenditure Prediction for Athletes and Non-Athletes from Ankle-Mounted Accelerometer and Heart Rate Monitor. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, P.G.; Green, D.J.; Etxebarria, N.; Pyne, D.B.; Saunders, P.U.; Minahan, C.L. Validation of Heart Rate Monitor-Based Predictions of Oxygen Uptake and Energy Expenditure. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2009, 23, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rising, R.; Harper, I.; Fontvielle, A.; Ferraro, R.; Spraul, M.; Ravussin, E. Determinants of total daily energy expenditure: Variability in physical activity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1994, 59, 800–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagim, A.R.; Jones, M.T.; Askow, A.T.; Luedke, J.; Erickson, J.L.; Fields, J.B.; Kerksick, C.M. Sex Differences in Resting Metabolic Rate among Athletes and Association with Body Composition Parameters: A Follow-Up Investigation. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2023, 8, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeyre, J.; Fellmann, N.; Vernet, J.; Delaître, M.; Chamoux, A.; Coudert, J.; Vermorel, M. Components and variations in daily energy expenditure of athletic and non-athletic adolescents in free-living conditions. Br. J. Nutr. 2000, 84, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human energy requirements. Scientific background papers from the Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation. October 17–24, 2001. Rome, Italy. Public Health Nutr. 2005, 8, 929–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsohn, A.; Scharhag-Rosenberger, F.; Cassel, M.; Weber, J.; de Guzman Guzman, A.; Mayer, F. Physical activity levels to estimate the energy requirement of adolescent athletes. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2011, 23, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, J.B.; Magee, M.K.; Jones, M.T.; Askow, A.T.; Camic, C.L.; Luedke, J.; Jagim, A.R. The accuracy of ten common resting metabolic rate prediction equations in men and women collegiate athletes. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2023, 23, 1973–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebine, N.; Rafamantanantsoa, H.H.; Nayuki, Y.; Yamanaka, K.; Tashima, K.; Ono, T.; Saitoh, S.; Jones, P.J.H. Measurement of total energy expenditure by the doubly labelled water method in professional soccer players. J. Sports Sci. 2002, 20, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morehen, J.C.; Bradley, W.J.; Clarke, J.; Twist, C.; Hambly, C.; Speakman, J.R.; Morton, J.P.; Close, G.L. The Assessment of Total Energy Expenditure During a 14-Day In-Season Period of Professional Rugby League Players Using the Doubly Labelled Water Method. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2016, 26, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.R.; King, R.F.G.J.; Duckworth, L.C.; Sutton, L.; Preston, T.; O’Hara, J.P.; Jones, B. Energy expenditure of rugby players during a 14-day in-season period, measured using doubly labelled water. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2018, 118, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morehen, J.C.; Rosimus, C.; Cavanagh, B.P.; Hambly, C.; Speakman, J.R.; Elliott-Sale, K.J.; Hannon, M.P.; Morton, J.P. Energy Expenditure of Female International Standard Soccer Players: A Doubly Labeled Water Investigation. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2022, 54, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.; Orme, P.; Naughton, R.J.; Close, G.L.; Milsom, J.; Rydings, D.; O’Boyle, A.; Di Michele, R.; Louis, J.; Hambly, C.; et al. Energy Intake and Expenditure of Professional Soccer Players of the English Premier League: Evidence of Carbohydrate Periodization. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2017, 27, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmans, N.Y.J.; Iedema, N.; Plasqui, G.; Wouters, L.; Saris, W.H.M.; van Loon, L.J.C.; van Dijk, J.-W. Energy expenditure and dietary intake in professional football players in the Dutch Premier League: Implications for nutritional counselling. J. Sports Sci. 2019, 37, 2759–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodruff, S.J.; Meloche, R.D. Energy Availability of Female Varsity Volleyball Players. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2013, 23, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanders, B.R.; Currier, B.S.; Harty, P.S.; Zabriskie, H.A.; Smith, C.R.; Stecker, R.A.; Richmond, S.R.; Jagim, A.R.; Kerksick, C.M. Changes in Energy Expenditure, Dietary Intake, and Energy Availability Across an Entire Collegiate Women’s Basketball Season. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabriskie, H.A.; Currier, B.S.; Harty, P.S.; Stecker, R.A.; Jagim, A.R.; Kerksick, C.M. Energy Status and Body Composition Across a Collegiate Women’s Lacrosse Season. Nutrients 2019, 11, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-134-74270-7. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, L.; Jones, B.; Backhouse, S.H.; Boyd, A.; Hamby, C.; Menzies, F.; Owen, C.; Ramirez-Lopez, C.; Roe, S.; Samuels, B.; et al. Energy expenditure of international female rugby union players during a major international tournament: A doubly labelled water study. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. Physiol. Appl. Nutr. Metab. 2024, 49, 1340–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, N.; Deighton, K.; Cummins, C.; Whitehead, S.; Preston, T.; Jones, B. Isolated & Combined Wearable Technology Underestimate the Total Energy Expenditure of Professional Young Rugby League Players; A Doubly Labelled Water Validation Study. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36, 3398–3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasa, M.S.; Friborg, O.; Kristoffersen, M.; Pettersen, G.; Plasqui, G.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.K.; Rosenvinge, J.H. Energy expenditure, dietary intake and energy availability in female professional football players. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2023, 9, e001553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannon, M.P.; Parker, L.J.F.; Carney, D.J.; McKeown, J.; Speakman, J.R.; Hambly, C.; Drust, B.; Unnithan, V.B.; Close, G.L.; Morton, J.P. Energy Requirements of Male Academy Soccer Players from the English Premier League. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2021, 53, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stables, R.G.; Hannon, M.P.; Jacob, A.D.; Topping, O.; Costello, N.B.; Boddy, L.M.; Hambly, C.; Speakman, J.R.; Sodhi, J.S.; Close, G.L.; et al. Daily energy requirements of male academy soccer players are greater than age-matched non-academy soccer players: A doubly labelled water investigation. J. Sports Sci. 2023, 41, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naughton, M.; Jones, B.; Hendricks, S.; King, D.; Murphy, A.; Cummins, C. Quantifying the Collision Dose in Rugby League: A Systematic Review, Meta-analysis, and Critical Analysis. Sports Med.-Open 2020, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamlin, M.J.; Olsen, P.D.; Marshall, H.C.; Lizamore, C.A.; Elliot, C.A. Hypoxic Repeat Sprint Training Improves Rugby Player’s Repeated Sprint but Not Endurance Performance. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, D.; Gabbett, T.; Jenkins, D. The physical demands of Super 14 rugby union. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2011, 14, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, S.P.; Trewartha, G.; Higgitt, R.J.; El-Abd, J.; Stokes, K.A. The physical demands of elite English rugby union. J. Sports Sci. 2008, 26, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhini, M.; Hickner, R.C.; Naidoo, R.; Sookan, T. The physical demands of the match according to playing positions in a South African Premier Soccer League team. South Afr. J. Sports Med. 2024, 36, v36i1a16752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, J.; Sarmento, H.; Clemente, F.M.; Field, A.; Figueiredo, A.J. The Effect of Contextual Variables on Match Performance across Different Playing Positions in Professional Portuguese Soccer Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualtieri, A.; Rampinini, E.; Dello Iacono, A.; Beato, M. High-speed running and sprinting in professional adult soccer: Current thresholds definition, match demands and training strategies. A systematic review. Front. Sports Act. Living 2023, 5, 1116293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagim, A.R.; Murphy, J.; Schaefer, A.Q.; Askow, A.T.; Luedke, J.A.; Erickson, J.L.; Jones, M.T. Match Demands of Women’s Collegiate Soccer. Sports 2020, 8, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Abdelkrim, N.; El Fazaa, S.; El Ati, J. Time-motion analysis and physiological data of elite under-19-year-old basketball players during competition. Br. J. Sports Med. 2007, 41, 69–75, discussion 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deutsch, M.U.; Maw, G.J.; Jenkins, D.; Reaburn, P. Heart rate, blood lactate and kinematic data of elite colts (under-19) rugby union players during competition. J. Sports Sci. 1998, 16, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagim, A.R.; Harty, P.S.; Jones, M.T.; Fields, J.B.; Magee, M.; Smith-Ryan, A.E.; Luedke, J.; Kerksick, C.M. Fat-Free Mass Index in Sport: Normative Profiles and Applications for Collegiate Athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2024, 38, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, M.K.; Fields, J.B.; Jagim, A.R.; Jones, M.T. Fat-Free Mass Index in a Large Sample of National Collegiate Athletic Association Men and Women Athletes From a Variety of Sports. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2024, 38, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, J.B.; Metoyer, C.J.; Casey, J.C.; Esco, M.R.; Jagim, A.R.; Jones, M.T. Comparison of Body Composition Variables Across a Large Sample of National Collegiate Athletic Association Women Athletes From 6 Competitive Sports. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 2452–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.M.; Santos, D.A.; Matias, C.N.; Minderico, C.S.; Schoeller, D.A.; Sardinha, L.B. Total energy expenditure assessment in elite junior basketball players: A validation study using doubly labeled water. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 1920–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.M.; Matias, C.N.; Santos, D.A.; Thomas, D.; Bosy-Westphal, A.; Müller, M.J.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Sardinha, L.B. Energy Balance over One Athletic Season. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 1724–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, A.K.; Heikura, I.A.; Tenforde, A.; Mountjoy, M. Energy Availability in Athletics: Health, Performance, and Physique. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2019, 29, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study [Reference] | Sport | Sex | Subjects | Measurement Period | Height (cm) & Weight (kg) | Training/Match Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rugby | ||||||

| Wilson et al., 2024 [31] | Rugby | Females | n = 15, Age (y) = 27 ± 2.6 Rugby Union players, Forwards & Backs | 14 days (tournament) | Height: 170 ± 5.7 FFM: 59.6 ± 5.5 FM: 17.3 ± 6 | 14-day interval w/8 training days, three rest days, 1 travel day, 2 match days |

| Smith et al., 2018 [23] | Rugby | Males | n = 14 (5 U16, 5 U20, 4 U24), Age: U16 (15.2 ± 0.8), U20 (17.6 ± 1.1), U24 (23 ± 1.8) Rugby League Players | 14 days (in-season) | Height: U16 (180.8 ± 7), U20 (176.8 ± 3.8), U24 (184.7 ± 2.5) Weight: U16 (79.3 ± 17.1), U20 (87.6 ± 8.8), U24 (98.3 ± 4.8) | 2–9 light training days 1–7 heavy training days 0–2 match days 4–8 rest days |

| Smith et al., 2018 [23] | Rugby | Males | n = 13 [5 U16, 4 U20, 4 U24], Age: U16 (15.6 ± 0.5), U20 (18.3 ± 0.5), U24 (23 ± 0.8) Rugby Union Players | 14 days (in-season) | Height: U16 (182.1 ± 7.5), U20 (178.1 ± 3.5), U24 (184.4 ± 3.2) Weight: U16 (85.4 ± 17.3), U20 (85.1 ± 8.3), U24 (99.4 ± 16.8) | 0–3 light training days 3–7 heavy training days 0–2 match days 7–10 rest days |

| Smith et al., 2018 [23] | Rugby | Males | n = 10 [5 RL, 5 RU], Age: RL (15.2 ± 0.8), RU (15.6 ± 0.5) U16 Players (Combined Leagues) | 14 days (in-season) | Height: RL (180.8 ± 7), RU (182.1 ± 7.5) Weight: RL (79.3 ± 17.1), RU (85.4 ± 17.3) | 0–4 light training days 3–5 heavy training days 0–2 match days 8–10 rest days |

| Smith et al., 2018 [23] | Rugby | Males | n = 9 [5 RL, 4 RU], Age: RL (17.6 ± 1.1), RU (18.3 ± 0.5) U20 Players (Combined Leagues) | 14 days (in-season) | Height: RL (176.8 ± 3.8), RU (178.1 ± 3.5) Weight: RL (87.6 ± 8.8), RU (85.1 ± 8.3) | 1–2 light training days 4–7 heavy training days 0–2 match days 5–9 rest days |

| Smith et al., 2018 [23] | Rugby | Males | n = 8 [4 RL, 4 RU], Age: RL (23 ± 1.8), RU (23 ± 0.8) U24 Players (Combined Leagues) | 14 days (in-season) | Height: RL (184.7 ± 2.5), RU (184.4 ± 3.2) Weight: RL (98.3 ± 4.8), RU (99.4 ± 16.8) | 1–9 light training days 1–4 heavy training days 0–2 match days 4–9 rest days |

| Morehen et al., 2016 [22] | Rugby | Males | n = 6, Age: NA Rugby League Players, Forwards and Backs | 14 days (in-season) | Height: 182.8 ± 2.7 Weight: 94.7 ± 6.7 | 2 weeks of structured training, including 4 rest days, 8 training days, 2 game days |

| Costello et al., 2022 [32] | Rugby | Males | n = 8 [6 pre-season, 7 in-season], Age: 17 ± 1 European Super League Academy | 7 days (in-season) + 14 days (pre-season) | Height: 179.5 ± 8.7 Weight: 90.5 ± 11.4 | Pre-season: 13 days with 10 training sessions, 10 field sessions, 4 rest days. In-season: 3 training sessions, 3 field sessions, 2 rest days, 1 match |

| Morehen et al., 2022 [24] | Soccer | Females | n = 24, Age: NA Professional International Players | 12 days (pre-season) | Height: 168.1 ± 5.9 Weight: 62.1 ± 4.7 | 9-day training camp including 4 training days, 1 rest day, 2 travel days, 2 match days + 3 days at home |

| Dasa et al., 2023 [33] | Soccer | Females | n = 51, Age: 22 ± 4 Both professional and elite youth Norwegian players | 14-day observational (in-season) | Height: 169 ± 7 Weight: 63.9 ± 6.6 | 1.7 ± 1.5 match days, and 10.7 ± 0.9 training days |

| Anderson et al., 2017 [25] | Soccer | Males | n = 6, Age:27 ± 3 Premier League | 7 days (in-season) | Height: 180 ± 7 Weight: 80.5 ± 8.7 | 2 game days, 5 days “normal in-season training” |

| Hannon et al., 2021 [34] | Soccer | Males | n = 8, Age: 12.2 ± 0.4 U12/13 EPL Soccer Academy | 14 days (in-season) | Height: 157.1 ± 4.1 Weight: 43.0 ± 4.8 | 6 rest days, 6 training days, 2 match days |

| Hannon et al., 2021 [34] | Soccer | Males | n = 8, Age: 15.0 ± 0.2 U15 EPL Soccer Academy | 14 days (in-season) | Height: 173.9 ± 5.6 Weight: 56.8 ± 6.2 | 5 rest days, 6 training days, 3 match days |

| Hannon et al., 2021 [34] | Soccer | Males | n = 8, Age: 17.5 ± 0.4 U18 EPL Soccer Academy | 14 days (in-season) | Height: 181.2 ± 5.2 Weight: 73.1 ± 8.1 | 4 rest days, 6 training days, 4 match days |

| Stables et al., 2023 [35] | Soccer | Males | n = 8, Age: 13.4 ± 0.2 Cat1 Premier League Academy | 14 days (in-season) | Height: 165.7 ± 7.2 Weight: 51.2 ± 8.4 | 2 match days, 8 training days, 4 rest days |

| Stables et al., 2023 [35] | Soccer | Males | n = 6, Age: 13.1 ± 0.5 Non-Academy Players | 14 days (in-season) | Height: 162.9 ± 6.4 Weight: 52.7 ± 12.4 | 2 match days, 2 training days, 10 rest days |

| Ebine et al., 2002 [21] | Soccer | Males | n = 7, Age: 22.1 ± 1.9 Professional Players | 7 days (in-season) | Height: 175 ± 5 Weight: 69.8 ± 4.7 | 2 match days, 5 days “normal training regime” |

| Brinkmans et al., 2019 [26] | Soccer | Males | n = 41, Age: 23 ± 4 Dutch Eredivisie Pro Players (Total) | 3–4 weeks (in-season) | Height: 182 ± 6 Weight: 77.6 ± 8.0 | 2.3 ± 0.5 matches played, 8.7 ± 1 training sessions, 3.1 ± 1 rest days over a 14-day study period |

| Brinkmans et al., 2019 [26] | Soccer | Males | n = 12, Age: 25 ± 4 Dutch Eredivisie (Defender) | 3–4 weeks (in-season) | Height: 185 ± 4 Weight: 79.0 ± 7.4 | |

| Brinkmans et al., 2019 [26] | Soccer | Males | n = 13, Age: 22 ± 4 Dutch Eredivisie (Midfielder) | 3–4 weeks (in-season) | Height: 179 ± 5 Weight: 71.7 ± 4.9 | |

| Brinkmans et al., 2019 [26] | Soccer | Males | n = 12, Age: 21 ± 3 Dutch Eredivisie (Attacker) | 3–4 weeks (in-season) | Height: 181 ± 8 Weight: 78.5 ± 7.1 | |

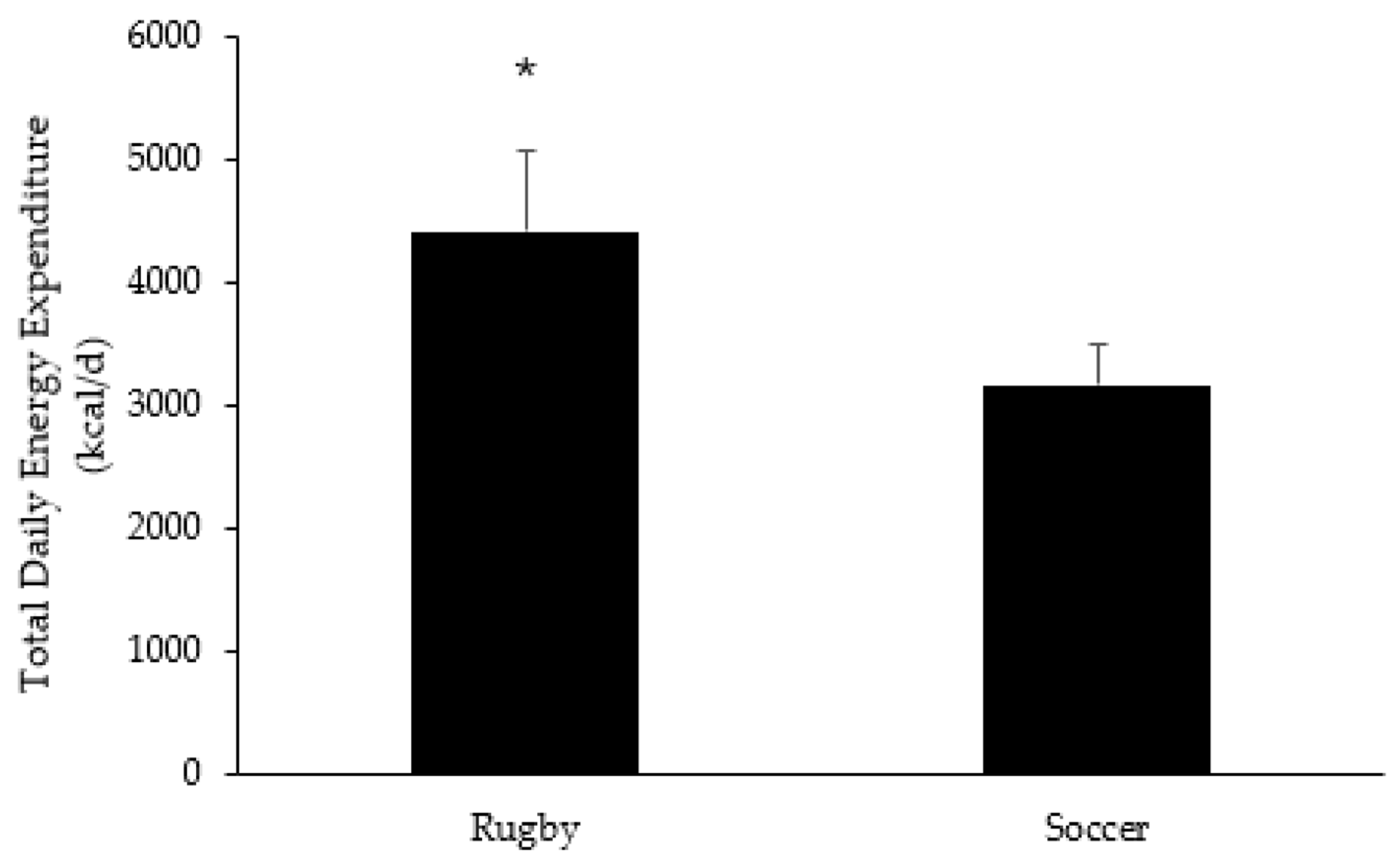

| Reference | Sport | N (Sex) | Skill | TDEE (kcal·kg−1·Day−1) | rTDEE (kcal/kg/Day) | RMR (kcal·d−1) | PAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [31] | Rugby | 15 (F) | Pro | 3229 ± 545 | NA | 1578 ± 223 | 2.0 ± 0.3 |

| [23] | Rugby | 14 (M) | Pro | 4369 ± 979 | 50 ± 10 | 2366 ± 296 | 1.90 ± 0.36 |

| [23] | Rugby | 13 (M) | Pro | 4365 ± 1122 | 49 ± 9 | 2123 ± 269 | 2.07 ± 0.46 |

| [23] | Rugby | 10 (M) | U16 | 4010 ± 744 | 50 ± 8 | 2168 ± 353 | 1.91 ± 0.20 |

| [23] | Rugby | 9 (M) | U20 | 4414 ± 688 | 51 ± 9 | 2318 ± 335 | 1.93 ± 0.33 |

| [23] | Rugby | 8 (M) | U24 | 4761 ± 1523 | 48 ± 11 | 2232 ± 221 | 2.14 ± 0.64 |

| [22] | Rugby | 6 (M) | Pro | 5378 ± 645 | NA | 1878 ± 96 | 2.86 ± 0.37 |

| [32] | Rugby | 7 (M) | Pro | 3862 ± 184 | NA | NA | NA |

| [32] | Rugby | 6 (M) | Pro | 4384 ± 726 | NA | NA | NA |

| [24] | Soccer | 24 (F) | Elite | 2693 ± 432 | 43 ± 6 | 1504 ± 314 | 1.79 ± 0.24 |

| [33] | Soccer | 51 (F) | Pro | 2918 ± 322 | 45.4 | NA | 2.00 ± 0.31 |

| [25] | Soccer | 6 (M) | Pro | 3566 ± 585 | NA | NA | NA |

| [34] | Soccer | 8 (M) | U12 | 2859 ± 265 | 66.5 ± 9.6 | 1892 ± 211 | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

| [34] | Soccer | 8 (M) | U15 | 3029 ± 262 | 53.3 ± 7.4 | 2023 ± 162 | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

| [34] | Soccer | 8 (M) | U18 | 3586 ± 487 | 73.1 ± 8.1 | 2236 ± 93 | 1.6 ± 02 |

| [35] | Soccer | 8 (M) | Elite | 3380 ± 517 | 66 ± 6 | 1824 ± 90 | 1.85 ± 0.30 |

| [35] | Soccer | 6 (M) | Youth | 2641 ± 308 | 52 ± 10 | 1699 ± 45 | 1.55 ± 0.19 |

| [21] | Soccer | 7 (M) | Pro | 3532 ± 408 | 50.6 ± 6.8 | 1674 ± 307 | 2.11 + 0.30 |

| [26] | Soccer | 41 (M) | Pro | 3285 ± 354 | 42.4 ± 3.5 | 1877 ± 246 | 1.75 ± 0.13 |

| [26] | Soccer | 4 (M) | Pro | 3365 ± 231 | 37.6 ± 2.9 | 2052 ± 215 | 1.64 ± 0.13 |

| [26] | Soccer | 12 (M) | Pro | 3333 ± 489 | 42.0 ± 3.3 | 1894 ± 327 | 1.76 ± 0.16 |

| [26] | Soccer | 13 (M) | Pro | 3180 ± 294 | 44.4 ± 3.2 | 1787 ± 204 | 1.78 ± 0.12 |

| [26] | Soccer | 12 (M) | Pro | 3322 ± 297 | 42.4 ± 2.6 | 1888 ± 206 | 1.76 ± 0.11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Skalitzky, B.; Fields, J.B.; Jones, M.T.; Kerksick, C.M.; Jagim, A.R. Differences in Total Daily Energy Expenditure Across Field Sports: A Narrative Review. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 474. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040474

Skalitzky B, Fields JB, Jones MT, Kerksick CM, Jagim AR. Differences in Total Daily Energy Expenditure Across Field Sports: A Narrative Review. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2025; 10(4):474. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040474

Chicago/Turabian StyleSkalitzky, Brenen, Jennifer B. Fields, Margaret T. Jones, Chad M. Kerksick, and Andrew R. Jagim. 2025. "Differences in Total Daily Energy Expenditure Across Field Sports: A Narrative Review" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 10, no. 4: 474. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040474

APA StyleSkalitzky, B., Fields, J. B., Jones, M. T., Kerksick, C. M., & Jagim, A. R. (2025). Differences in Total Daily Energy Expenditure Across Field Sports: A Narrative Review. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 10(4), 474. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040474