Inspiratory Muscle Performance and Its Correlates Among Division I American Football Players

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

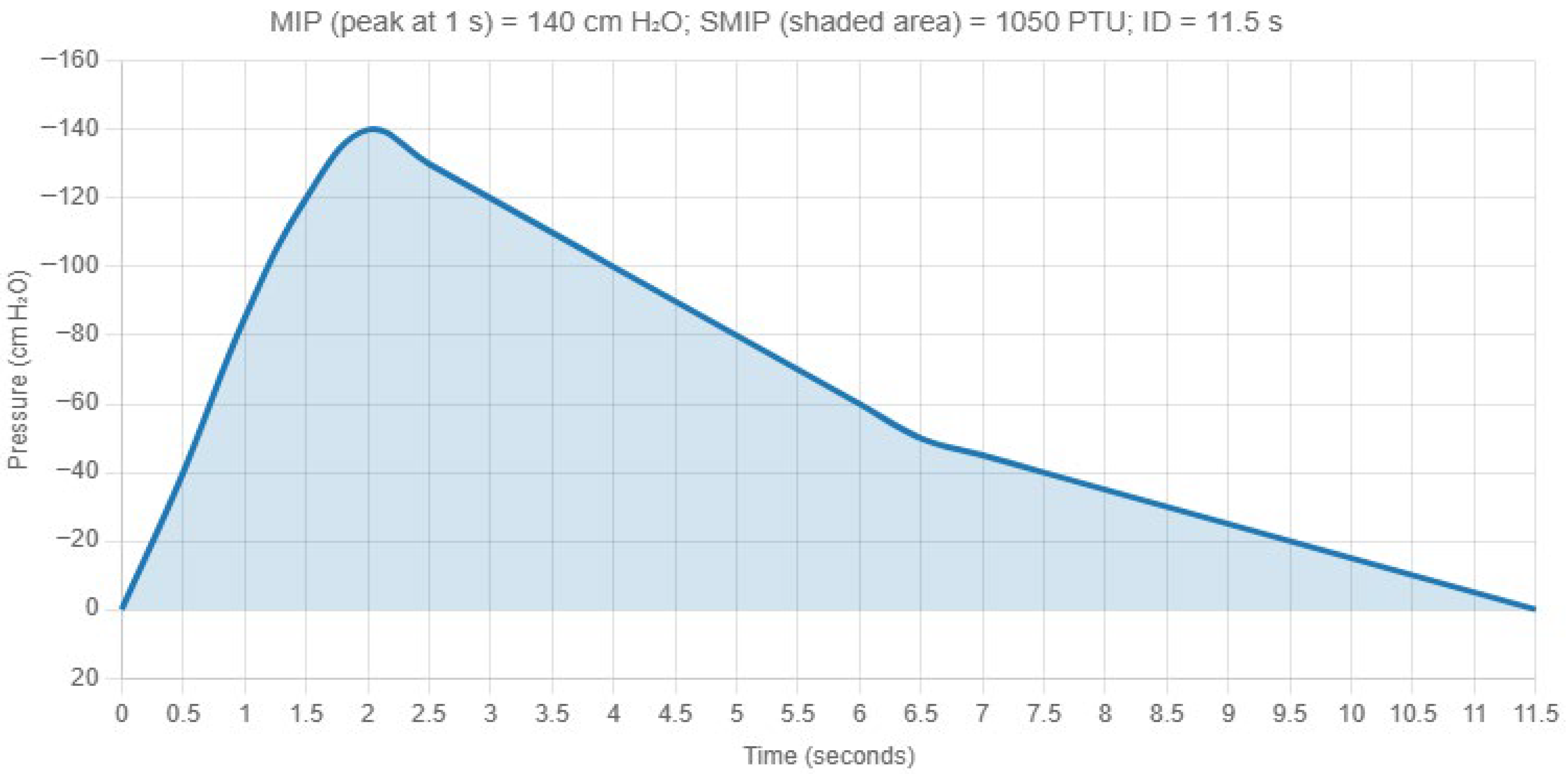

2.3. Test of Incremental Respiratory Endurance (TIRE)

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Bivariate Analyses

3.2.1. Results of Correlation Analyses of Inspiratory Muscle Performance with Anthropometrics

3.2.2. Results of Correlation Analyses Between Inspiratory Muscle Performance and Year in School

3.2.3. Comparison of Inspiratory Performance Between Offensive vs. Defensive Players

4. Discussion

4.1. Inspiratory Muscle Performance and Football-Specific Demands

4.2. Inspiratory Muscle Training

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iosia, M.F.; Bishop, P.A. Analysis of exercise-to-rest ratios during division IA televised football competition. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2008, 22, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokha, M.; Berrocales, M.; Rohman, A.; Schafer, A.; Stensland, J.; Petruzzelli, J.; Nasri, A.; Thompson, T.; Taha, E.; Bommarito, P. Morphological and Performance Biomechanics Profiles of Draft Preparation American-Style Football Players. Biomechanics 2024, 4, 685–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, T.A.; Carbuhn, A.F.; Stanforth, P.R.; Oliver, J.M.; Keller, K.A.; Dengel, D.R. Body Composition and Bone Mineral Density of Division 1 Collegiate Football Players: A Consortium of College Athlete Research Study. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 1339–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pincivero, D.M.; Bompa, T.O. A physiological review of American football. Sports Med. 1997, 23, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dow, B.; Doucet, D.; Vemu, S.M.; Boddapati, V.; Marco, R.A.W.; Hirase, T. Characterizing neck injuries in the national football league: A descriptive epidemiology study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2023, 24, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canseco, J.A.; Franks, R.R.; Karamian, B.A.; Divi, S.N.; Reyes, A.A.; Mao, J.Z.; Al Saiegh, F.; Donnally, C.J., 3rd; Schroeder, G.D.; Harrop, J.S.; et al. Overview of Traumatic Brain Injury in American Football Athletes. Clin. J. Sport. Med. 2022, 32, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, A.; Morris, S.N.; Powell, J.R.; Boltz, A.J.; Robison, H.J.; Collins, C.L. Epidemiology of Injuries in National Collegiate Athletic Association Men’s Football: 2014–2015 Through 2018–2019. J. Athl. Train. 2021, 56, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Viana, R.; Alexandrino, A. Effects of Inspiratory Muscle Training on Performance Athletes: A Systematic Review. In Congress of the Portuguese Society of Biomechanics; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 605–620. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Lázaro, D.; Gallego-Gallego, D.; Corchete, L.A.; Fernández Zoppino, D.; González-Bernal, J.J.; García Gómez, B.; Mielgo-Ayuso, J. Inspiratory Muscle Training Program Using the PowerBreath®: Does It Have Ergogenic Potential for Respiratory and/or Athletic Performance? A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 6703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, A.K.; Romer, L.M. Respiratory muscle training in healthy humans: Resolving the controversy. Int. J. Sports Med. 2004, 25, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, M.J.; Mantilla, C.B.; Sieck, G.C. Breathing: Motor Control of the Diaphragm. Physiology 2018, 33, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaduman, E.; Bostancı, O.; Bayram, L. Respiratory muscle strength and pulmonary functions in athletes: Differences by BMI classifications. J. Men’s Health 2022, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, B.H.; Dawes, J.; Smith, D.; Johnson, Q. Kinanthropometric Characteristic Comparisons of NCAA Division I Offensive and Defensive Linemen Spanning 8 Decades. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36, 3404–3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, B.H.; Conchola, E.G.; Glass, R.G.; Thompson, B.J. Longitudinal Morphological and Performance Profiles for American, NCAA Division I Football Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 2347–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulrahman, M.T.; Mahmood, M.H. Relation Between the Body Composition and Strength of Respiratory Muscles. European J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2024, 11, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, T. The Influence of Peak Force, Rate of Force Development, and Countermovement Jump Metrics in Division II Collegiate Football Players. Master’s Thesis, University of Central Oklahoma, Edmond, OK, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- McGill, S. Core training: Evidence translating to better performance and injury prevention. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2010, 32, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, P.W.; Gandevia, S.C. Activation of the human diaphragm during a repetitive postural task. J. Physiol. 2000, 522, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhea, M.R.; Hunter, R.L.; Hunter, T.J. Competition Modeling of American Football: Observational Data and Implications for High School, Collegiate, and Professional Player Conditioning. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2006, 20, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, L.M.; Polkey, M.I. Exercise-induced respiratory muscle fatigue: Implications for performance. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008, 104, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, J.D.; Guenette, J.A.; Rupert, J.L.; McKenzie, D.C.; Sheel, A.W. Inspiratory muscle training attenuates the human respiratory muscle metaboreflex. J. Physiol. 2007, 584, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorca-Santiago, J.; Jiménez, S.L.; Pareja-Galeano, H.; Lorenzo, A. Inspiratory Muscle Training in Intermittent Sports Modalities: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, C.A.; Wetter, T.J.; St. Croix, C.M.; Pegelow, D.F.; Dempsey, J.A. Effects of Respiratory Muscle Work on Exercise Performance. J. App Phys. 2000, 89, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.C.; Chang, H.Y.; Ho, C.C.; Lee, P.F.; Chou, Y.C.; Tsai, M.W.; Chou, L.W. Effects of 4-Week Inspiratory Muscle Training on Sport Performance in College 800-Meter Track Runners. Medicina 2021, 57, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohya, T.; Kusanagi, K.; Koizumi, J.; Ando, R.; Katayama, K.; Suzuki, Y. Effect of Moderate- or High-Intensity Inspiratory Muscle Strength Training on Maximal Inspiratory Mouth Pressure and Swimming Performance in Highly Trained Competitive Swimmers. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2022, 17, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yañez-Sepulveda, R.; Alvear-Ordenes, I.; Tapia-Guajardo, A.; Verdugo-Marchese, H.; Cristi-Montero, C.; Tuesta, M. Inspiratory muscle training improves the swimming performance of competitive young male sprint swimmers. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2021, 61, 1348–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirino, C.; Marostegan, A.B.; Hartz, C.S.; Moreno, M.A.; Gobatto, C.A.; Manchado-Gobatto, F.B. Effects of Inspiratory Muscle Warm-Up on Physical Exercise: A Systematic Review. Biology 2023, 12, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marostegan, A.B.; Gobatto, C.A.; Rasteiro, F.M.; Hartz, C.S.; Moreno, M.A.; Manchado-Gobatto, F.B. Effects of different inspiratory muscle warm-up loads on mechanical, physiological and muscle oxygenation responses during high-intensity running and recovery. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Min | Max | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| Height (in) | 68 | 81 | 74.3 |

| Weight (kg) | 74.84 | 151.95 | 108.13 |

| BMI | 21.87 | 40.78 | 30.21 |

| Year in School | 1 | 6 | 2.87 |

| MIP (cmH2O) | 46 | 187 | 110.76 |

| SMIP (PTU) | 12.30 | 1571 | 651.69 |

| ID (s) | 3.60 | 26.60 | 11.41 |

| Position (n) | MIP (cmH2O) | SMIP (PTU) | ID (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| QB (5) | 127.4 | 700.9 | 11.6 |

| RB (6) | 116.6 | 807.5 | 12.1 |

| WR (11) | 107.9 | 512.5 | 8.7 |

| TE (11) | 104.4 | 732.2 | 13.5 |

| OL (13) | 110.9 | 720 | 13.6 |

| DL (15) | 120.5 | 713.9 | 11 |

| LB (12) | 115.5 | 703.6 | 10.7 |

| DB (12) | 94.7 | 452 | 9.6 |

| Predictor | Inspiratory Metric | Spearman ρ (p-Value) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Height | MIP | 0.080 (0.463) | No correlation |

| Height | SMIP | 0.148 (0.175) | No correlation |

| Height | ID | 0.243 (0.024) | Weak positive correlation |

| Weight | MIP | 0.141 (0.197) | No correlation |

| Weight | SMIP | 0.122 (0.262) | No correlation |

| Weight | ID | 0.145 (0.184) | No correlation |

| BMI | MIP | 0.122 (0.263) | No correlation |

| BMI | SMIP | 0.077 (0.480) | No correlation |

| BMI | ID | 0.068 (0.531) | No correlation |

| Predictor | Inspiratory Metric | Spearman ρ (p-Value) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | MIP | 0.202 (0.062) | No correlation |

| Year | SMIP | 0.170 (0.117) | No correlation |

| Year | ID | 0.090 (0.409) | No correlation |

| Inspiratory Metric | Test | Statistic (p-Value) | Cohen’s d | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIP | t-test | −0.082 (0.935) | 0.02 | No difference |

| SMIP | Mann–Whitney | 1027.5 (0.338) | 0.18 | No difference |

| ID | Mann–Whitney | 1077.0 (0.165) | 0.23 | No difference |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feigenbaum, L.A.; Cahalin, L.P.; Ruiz, J.T.; Asken, T.; Cohen, M.I.; Scavo, V.A.; Kaplan, L.D.; Rapicavoli, J.L. Inspiratory Muscle Performance and Its Correlates Among Division I American Football Players. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 470. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040470

Feigenbaum LA, Cahalin LP, Ruiz JT, Asken T, Cohen MI, Scavo VA, Kaplan LD, Rapicavoli JL. Inspiratory Muscle Performance and Its Correlates Among Division I American Football Players. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2025; 10(4):470. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040470

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeigenbaum, Luis A., Lawrence P. Cahalin, Jeffrey T. Ruiz, Tristen Asken, Meryl I. Cohen, Vincent A. Scavo, Lee D. Kaplan, and Julia L. Rapicavoli. 2025. "Inspiratory Muscle Performance and Its Correlates Among Division I American Football Players" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 10, no. 4: 470. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040470

APA StyleFeigenbaum, L. A., Cahalin, L. P., Ruiz, J. T., Asken, T., Cohen, M. I., Scavo, V. A., Kaplan, L. D., & Rapicavoli, J. L. (2025). Inspiratory Muscle Performance and Its Correlates Among Division I American Football Players. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 10(4), 470. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040470