The Effects of Walking Exercise Using Water Inertial Load on Dynamic Balance Ability and Pain in Women Aged 65 Years and Older with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Clinical Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

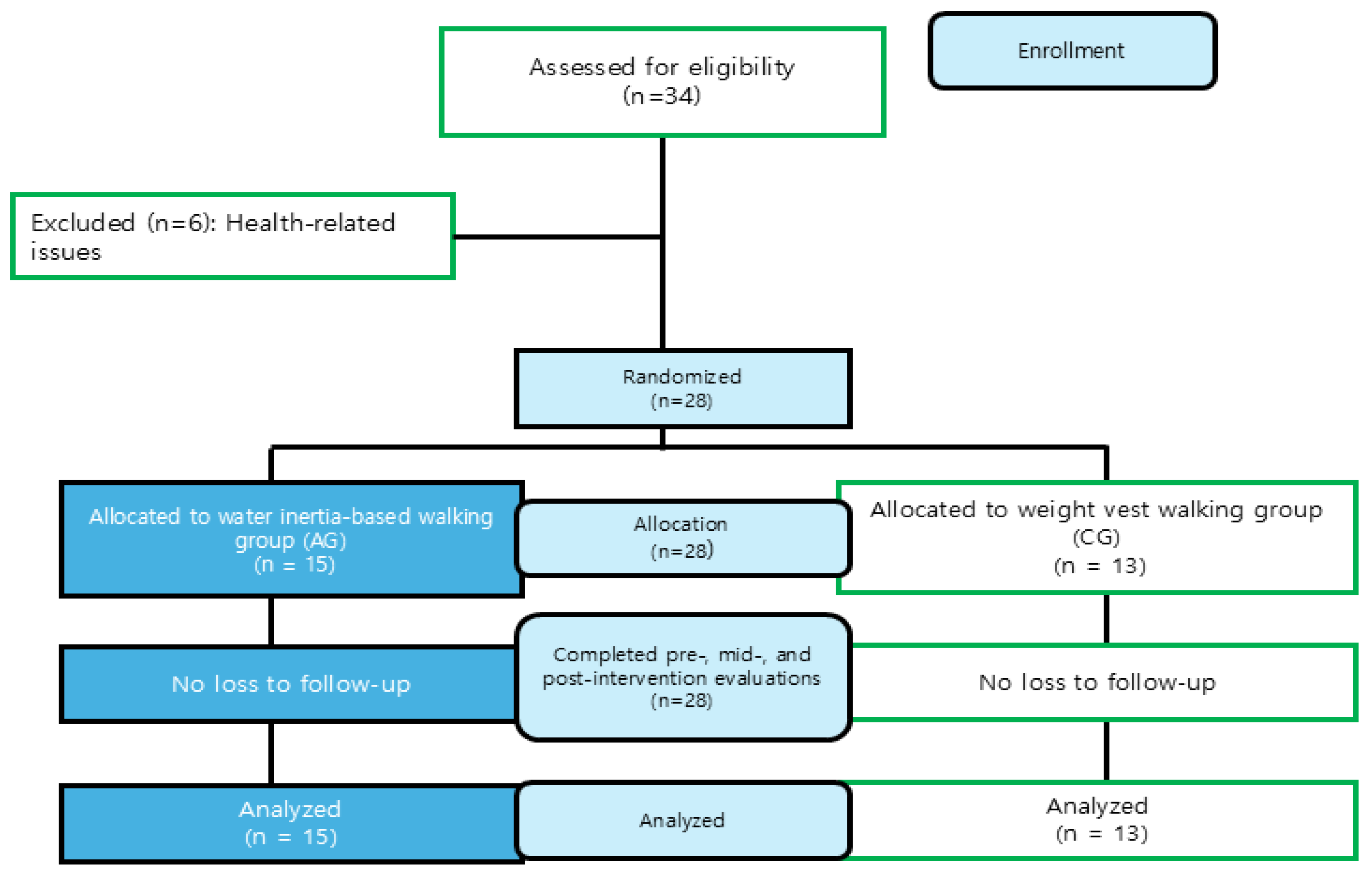

2.1. Participants

- (1)

- Individuals diagnosed with KOA with Kellgren–Lawrence (K-L) Grade 2–3 according to radiological assessments

- (2)

- Individuals who have been diagnosed with KOA for more than 3 years

- (3)

- Individuals without congenital deformities or musculoskeletal disorders in the foot, pelvis, or spine

- (1)

- Individuals with K-L Grade 0–1 or Grade 4

- (2)

- Individuals who have undergone lower limb surgery within the past year

- (3)

- Individuals with moderate or severe cardiovascular or respiratory diseases

- (4)

- Individuals with uncontrolled hypertension or diabetes

- (5)

- Individuals who have engaged in regular exercise during the past 6 months

- (6)

- Individuals with neurological disorders or acute inflammation and joint swelling

- (7)

- Individuals taking medications that could affect pain perception or balance

- (8)

- Individuals diagnosed with sarcopenia or other muscle-wasting disorders

2.2. Evaluation and Data Processing

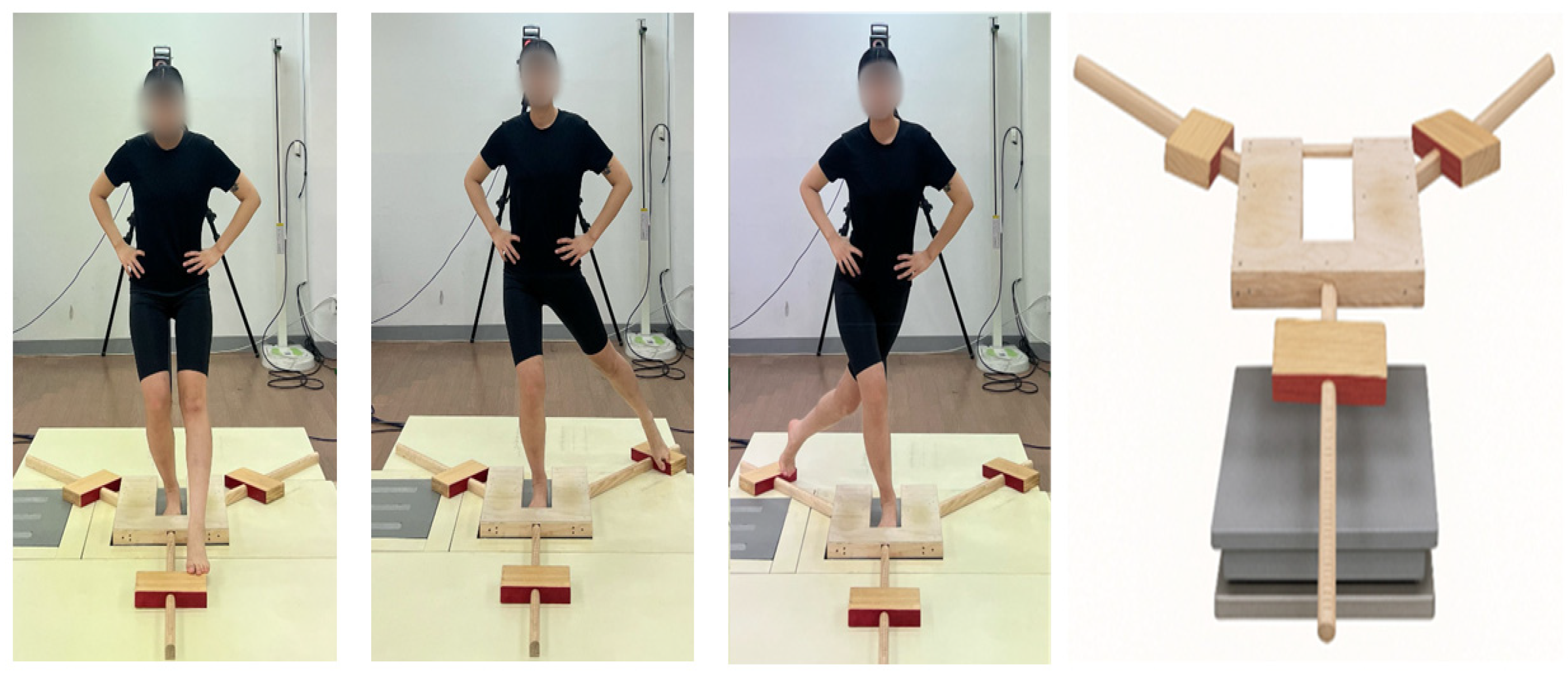

2.2.1. Y-Balance Test

2.2.2. Center of Pressure Analysis

2.2.3. Visual Analogue Scale

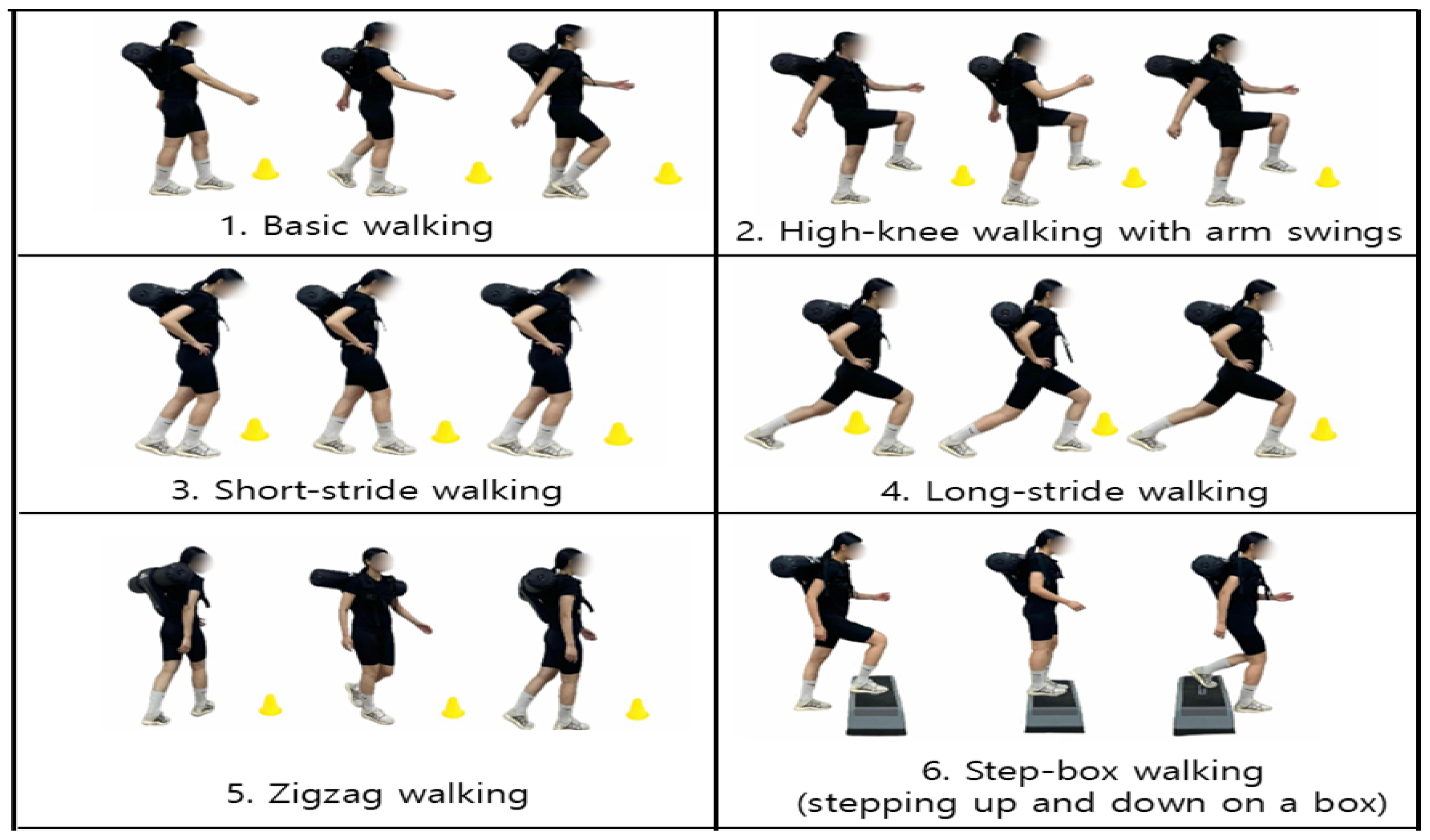

2.3. Exercise Intervention

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Change in YBT

3.2. Change in COP

3.3. Change in VAS

4. Discussion

- The intervention period was limited to eight weeks, which may have been insufficient to fully capture long-term functional changes.

- Exercise intensity was determined based on the subjective RPE, and objective physiological indicators were not incorporated.

- Because pain assessment was limited to a subjective measure (VAS), future studies should include objective physiological measurement methods such as electromyography (EMG) analysis.

- This study included only women aged 65 years and older as participants; therefore, generalization to men may be limited due to physiological differences between sexes.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- He, Q.; Luo, H.; Mei, J.; Wang, Z.; Sun, X.; Wang, L.; Xie, C. The association between accelerated biological aging and the risk of osteoarthritis: A cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1451737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, A.; Li, H.; Wang, D.; Zhong, J.; Chen, Y.; Lu, H. Global, regional prevalence, incidence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis in population-based studies. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 29–30, 100587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Doherty, M.; Peat, G.; Bierma-Zeinstra, M.A.; Arden, N.K.; Bresnihan, B.; Herrero-Beaumont, G.; Kirschner, S.; Leeb, B.F.; Lohmander, L.S.; et al. EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010, 69, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.G.D.; Damiani, P.; Marcon, A.C.Z.; Haupenthal, A.; Avelar, N.P.C.D. Influence of knee osteoarthritis on functional performance, quality of life and pain in older women. Fisioter. Em. Mov. 2020, 33, e003306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, P.A.; Bradford, J.C.; Brahmachary, P.; Ulman, S.; Robinson, J.L.; June, R.K.; Cucchiarini, M. Unraveling sex-specific risks of knee osteoarthritis before menopause: Do sex differences start early in life? Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2024, 32, 1032–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landry, S.C.; McKean, K.A.; Hubley-Kozey, C.L.; Stanish, W.D.; Deluzio, K.J. Neuromuscular and lower limb biomechanical differences exist between male and female elite adolescent soccer players during an unanticipated side-cut maneuver. Am. J. Sports Med. 2007, 35, 1888–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, B.C.; Laakkonen, E.K.; Lowe, D.A. Aging of the musculoskeletal system: How the loss of estrogen impacts muscle strength. Bone 2019, 123, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, D.H.; Han, K.D.; Hong, J.Y.; Park, J.H.; Bae, J.H.; Moon, Y.W.; Kim, J.G. Body composition is more closely related to the development of knee osteoarthritis in women than men: A cross-sectional study using the Fifth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES V-1, 2). Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2016, 24, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szilagyi, I.A.; Waarsing, J.H.; van Meurs, J.B.J.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.A.; Schiphof, D. A systematic review of the sex differences in risk factors for knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatology 2023, 62, 2037–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolio, L.; Lim, K.Y.; McKenzie, J.E.; Yan, M.K.; Estee, M.; Hussain, S.M.; Cicuttini, F.; Wluka, A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of neuropathic-like pain and/or pain sensitization in people with knee and hip osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2021, 29, 1096–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, T.W.; Felson, D.T. Mechanisms of Osteoarthritis (OA) Pain. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2018, 16, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overton, M.; Swain, N.; Falling, C.; Gwynne-Jones, D.; Fillingim, R.; Mani, R. Activity-related pain predicts pain and functional outcomes in people with knee osteoarthritis: A longitudinal study. Front. Pain Res. 2023, 3, 1082252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Yu, D.; Chen, X.; Chen, P.; Chen, N.; Shao, B.; Lin, Q.; Wu, F. Effects of proprioceptive exercise for knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2025, 6, 1596966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.S.; Liu, H.C.; Lee, S.P.; Kao, Y.W. Balance factors affecting the quality of life in patients with knee osteoarthritis. S Afr. J. Physiother. 2022, 78, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neptune, R.R.; Vistamehr, A. Dynamic balance during human movement: Measurement and control mechanisms. J. Biomech. Eng. 2019, 141, 070801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lespasio, M.J.; Piuzzi, N.S.; Husni, M.E.; Muschler, G.F.; Guarino, A.; Mont, M.A. Knee Osteoarthritis: A Primer. Perm. J. 2017, 21, 16–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arampatzis, A.; Karamanidis, K.; Mademli, L. Deficits in the way to achieve balance related to mechanisms of dynamic stability control in the elderly. J. Biomech. 2008, 41, 1754–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bierbaum, S.; Peper, A.; Karamanidis, K.; Arampatzis, A. Adaptational responses in dynamic stability during disturbed walking in the elderly. J. Biomech. 2010, 43, 2362–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plisky, P.J.; Gorman, P.P.; Butler, R.J.; Kiesel, K.B.; Underwood, F.B.; Elkins, B. The reliability of an instrumented device for measuring components of the star excursion balance test. N. Am. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2009, 4, 92–99. [Google Scholar]

- Plisky, P.J.; Rauh, M.J.; Kaminski, T.W.; Underwood, F.B. Star Excursion Balance Test as a predictor of lower extremity injury in high school basketball players. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2006, 36, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, S.W.; Teyhen, D.S.; Lorenson, C.L.; Warren, R.L.; Koreerat, C.M.; Straseske, C.A.; Childs, J.D. Y-balance test: A reliability study involving multiple raters. Mil. Med. 2013, 178, 1264–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipe, C.L.; Ramey, K.D.; Plisky, P.P.; Taylor, J.D. Y-Balance Test: A Valid and Reliable Assessment in Older Adults. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2019, 27, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Liu, P.; Xiao, F.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y. Review of the Upright Balance Assessment Based on the Force Plate. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipton, N.; Alderink, G.; Rhodes, S. Approximate entropy and velocity of center of pressure to determine postural stability: A pilot study. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudyk, A.M.; Winters, M.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Ashe, M.C.; Gould, J.S.; McKay, H. Destinations matter: The association between where older adults live and their travel behavior. J. Transp. Health 2015, 2, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, J.A.; Webster, K.E.; Levinger, P.; Singh, P.J.; Fong, C.; Taylor, N.F. A walking program for people with severe knee osteoarthritis did not reduce pain but may have benefits for cardiovascular health: A phase II randomised controlled trial. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2017, 25, 1969–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Kang, S.; Park, I. Effects of Unstable Exercise Using the Inertial Load of Water on Lower Extremity Kinematics and Center of Pressure During Stair Ambulation in Middle-Aged Women with Degenerative Knee Arthritis. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Park, I. Effects of Instability Neuromuscular Training Using an Inertial Load of Water on the Balance Ability of Healthy Older Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Park, I.B. Effects of Dynamic Stability Training with Water Inertia Load on Gait and Biomechanics in Older Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsick, E.M.; Montgomery, P.S.; Newman, A.B.; Bauer, D.C.; Harris, T. Measuring fitness in healthy older adults: The Health ABC Long Distance Corridor Walk. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2001, 49, 1544–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, P.D.; Arena, R.; Riebe, D.; Pescatello, L.S.; American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s new preparticipation health screening recommendations from ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription, ninth edition. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2013, 12, 215–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, S.; Wilson, C.S.; Becker, J. Kinematic and Kinetic Predictors of Y-Balance Test Performance. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2021, 16, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewski, M.; Zając, B.; Mika, A.; Golec, J. Do Hip and Ankle Strength as well as Range of Motion Predict Y-Balance Test-Lower Quarter Performance in Healthy Males? Preprint 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerards, M.H.G.; McCrum, C.; Mansfield, A.; Meijer, K. Perturbation-based balance training for falls reduction among older adults: Current evidence and implications for clinical practice. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2017, 17, 2294–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, Y.C.; Bhatt, T.S. Repeated-slip training: An emerging paradigm for prevention of slip-related falls among older adults. Phys. Ther. 2007, 87, 1478–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrum, C.; Bhatt, T.S.; Gerards, M.H.G.; Karamanidis, K.; Rogers, M.W.; Lord, S.R.; Okubo, Y. Perturbation-based balance training: Principles, mechanisms and implementation in clinical practice. Front. Sports Act. Living 2022, 4, 1015394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagger, K.L.; Harper, B. Center of Pressure Velocity and Dynamic Postural Control Strategies Vary During Y-Balance and Star Excursion Balance Testing. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2024, 19, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, X.; Fan, R.; Kong, J. What improvements do general exercise training and traditional Chinese exercises have on knee osteoarthritis? A narrative review based on biological mechanisms and clinical efficacy. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1395375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Kim, H.A.; Felson, D.T.; Xu, L.; Kim, D.H.; Nevitt, M.C.; Yoshimura, N.; Kawaguchi, H.; Lin, J.; Kang, X.; et al. Radiographic Knee Osteoarthritis and Knee Pain: Cross-sectional study from Five Different Racial/Ethnic Populations. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| AG (n = 15) | CG (n = 13) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 70.47 ± 1.77 | 70.77 ± 1.59 | 0.640 |

| Weight (kg) | 55.73 ± 5.84 | 59.01 ± 8.37 | 0.914 |

| Height (cm) | 154.39 ± 4.16 | 154.55 ± 3.91 | 0.273 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.59 ± 2.67 | 23.83 ± 3.32 | 0.293 |

| Training | 0~4 Weeks/Program | 5~8 Weeks/Program | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity | 9~11 RPE With Weight (3 kg) | 12~13 RPE With weight (4 kg) | |

| Laps | Weeks 1–2: 5 laps Weeks 3–4: 6 laps | Weeks 5–6: 7 laps Weeks 7–8: 8 laps | |

| Warm up | 1. Ankle and knee rotations 2. Hip joint rotations 3. Marching in place with arm swings 4. Trunk rotations with shoulder rolls | 1. Ankle and knee rotations 2. Hip joint rotations 3. Marching in place with arm swings 4. Trunk rotations with shoulder rolls | 10 min |

| Main | 1. Basic walking 2. High-knee walking with arm swings 3. Short-stride walking 4. Long-stride walking 5. Zigzag walking 6. Step-box walking (stepping up and down on a box) | 1. Basic walking 2. High-knee walking with arm swings 3. Short-stride walking 4. Long-stride walking 5. Zigzag walking 6. Step-box walking (stepping up and down on a box) | 30 min |

| Cool down | 1. Calf stretching 2. Hamstring stretching 3. Quadriceps stretching 4. Ankle pumping and rotation | 1. Calf stretching 2. Hamstring stretching 3. Quadriceps stretching 4. Ankle pumping and rotation | 10 min |

| Variables Time | AG Adjusted Mean (CI 95%) | CG Adjusted Mean (CI 95%) | p | ηp2 | Wilcoxon (AG) p | r | Wilcoxon (CG) p | r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YBT Mid | 88.65 (85.87–91.43) | 84.29 (81.29–87.28) | 0.041 | 0.16 | 0–4 weeks 0.001 | 0.88 | 0–4 weeks 0.001 | 0.88 |

| YBT Post | 92.50 (87.64–97.36) | 82.89 (77.65–88.13) | 0.012 | 0.23 | 4–8 weeks 0.036 | 0.54 | 4–8 weeks 0.972 | 0.01 |

| 0–8 weeks 0.001 | 0.88 | 0–8 weeks 0.006 | 0.77 |

| Variables | Time | AG Adjusted Mean (CI 95%) | CG Adjusted Mean (CI 95%) | p | ηp2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANT | AP Velocity | Mid | 0.24 (0.19–0.28) | 0.29 (0.24–0.34) | 0.120 | 0.09 |

| (m/s) | Post | 0.20 (0.17–0.24) | 0.27 (0.23–0.31) | 0.012 | 0.23 | |

| ML Velocity | Mid | 0.16 (0.12–0.20) | 0.21 (0.17–0.26) | 0.096 | 0.11 | |

| (m/s) | Post | 0.15 (0.12–0.18) | 0.20 (0.17–0.23) | 0.022 | 0.19 | |

| PM | AP Velocity | Mid | 0.21 (0.18–0.24) | 0.24 (0.20–0.27) | 0.162 | 0.08 |

| (m/s) | Post | 0.22 (0.18–0.25) | 0.23 (0.20–0.27) | 0.437 | 0.02 | |

| ML Velocity | Mid | 0.12 (0.09–0.14) | 0.15 (0.12–0.18) | 0.098 | 0.11 | |

| (m/s) | Post | 0.12 (0.10–0.14) | 0.15 (0.13–0.17) | 0.096 | 0.11 | |

| PL | AP Velocity | Mid | 0.24 (0.20–0.28) | 0.27 (0.23–0.31) | 0.366 | 0.03 |

| (m/s) | Post | 0.25 (0.20–0.29) | 0.26 (0.22–0.31) | 0.603 | 0.01 | |

| ML Velocity | Mid | 0.11 (0.08–0.13) | 0.14 (0.11–0.16) | 0.065 | 0.13 | |

| (m/s) | Post | 0.12 (0.10–0.15) | 0.13 (0.10–0.15) | 0.693 | 0.01 |

| Variables Time | AG Adjusted Mean (CI 95%) | CG Adjusted Mean (CI 95%) | p | ηp2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS Mid | 2.01 (1.39–2.62) | 2.76 (2.10–3.43) | 0.115 | 0.10 |

| VAS Post | 1.77 (1.09–2.45) | 1.96 (1.23–2.70) | 0.702 | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chu, M.J.; Lee, C.K.; Kim, H.J.; Park, I.B. The Effects of Walking Exercise Using Water Inertial Load on Dynamic Balance Ability and Pain in Women Aged 65 Years and Older with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040469

Chu MJ, Lee CK, Kim HJ, Park IB. The Effects of Walking Exercise Using Water Inertial Load on Dynamic Balance Ability and Pain in Women Aged 65 Years and Older with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2025; 10(4):469. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040469

Chicago/Turabian StyleChu, Moon Jung, Chae Kwan Lee, Hyun Ju Kim, and Il Bong Park. 2025. "The Effects of Walking Exercise Using Water Inertial Load on Dynamic Balance Ability and Pain in Women Aged 65 Years and Older with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Clinical Trial" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 10, no. 4: 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040469

APA StyleChu, M. J., Lee, C. K., Kim, H. J., & Park, I. B. (2025). The Effects of Walking Exercise Using Water Inertial Load on Dynamic Balance Ability and Pain in Women Aged 65 Years and Older with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 10(4), 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040469