Biocompatibility of 3D-Printed Methacrylate for Hearing Devices

Abstract

:1. Introduction

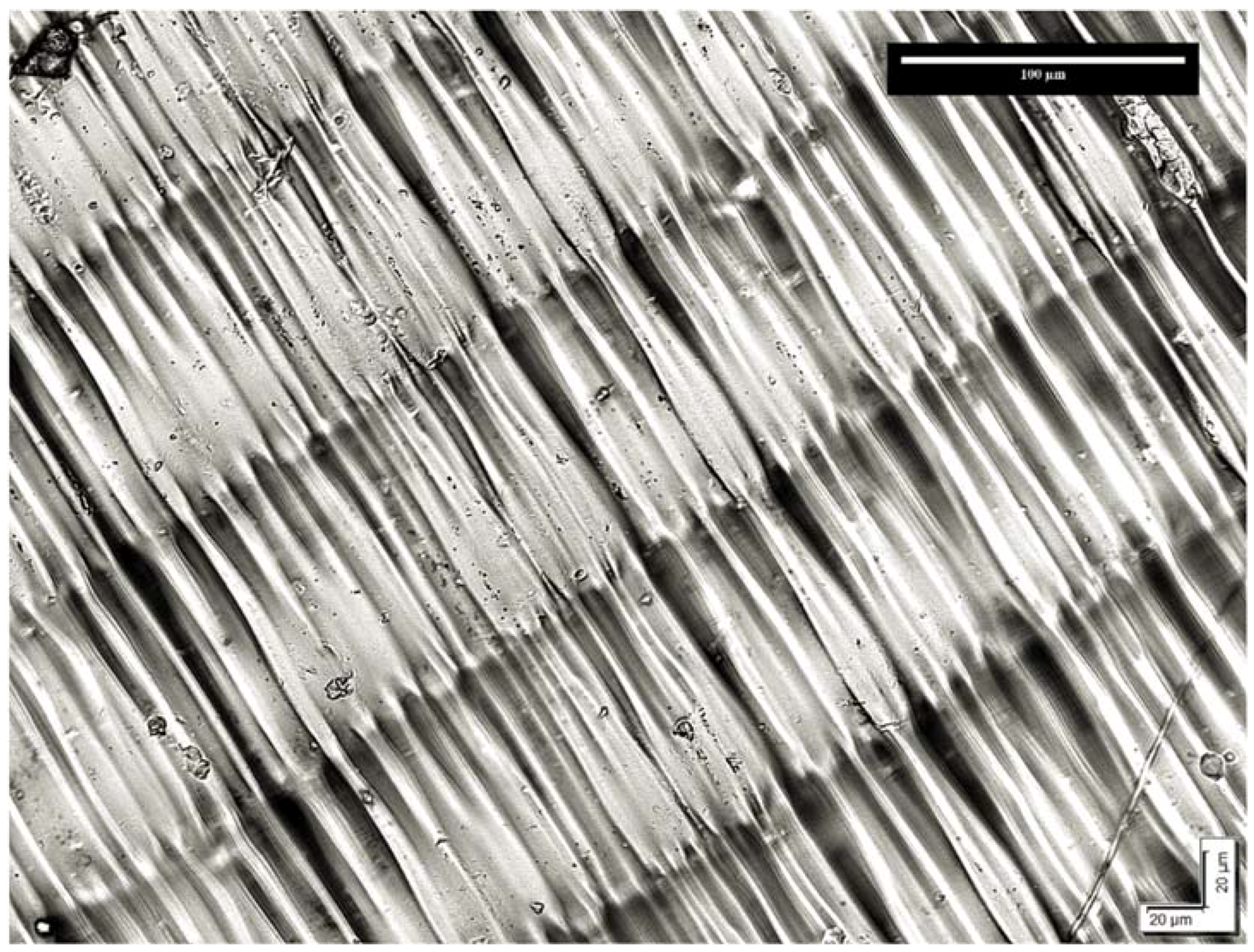

2. Materials and Methods

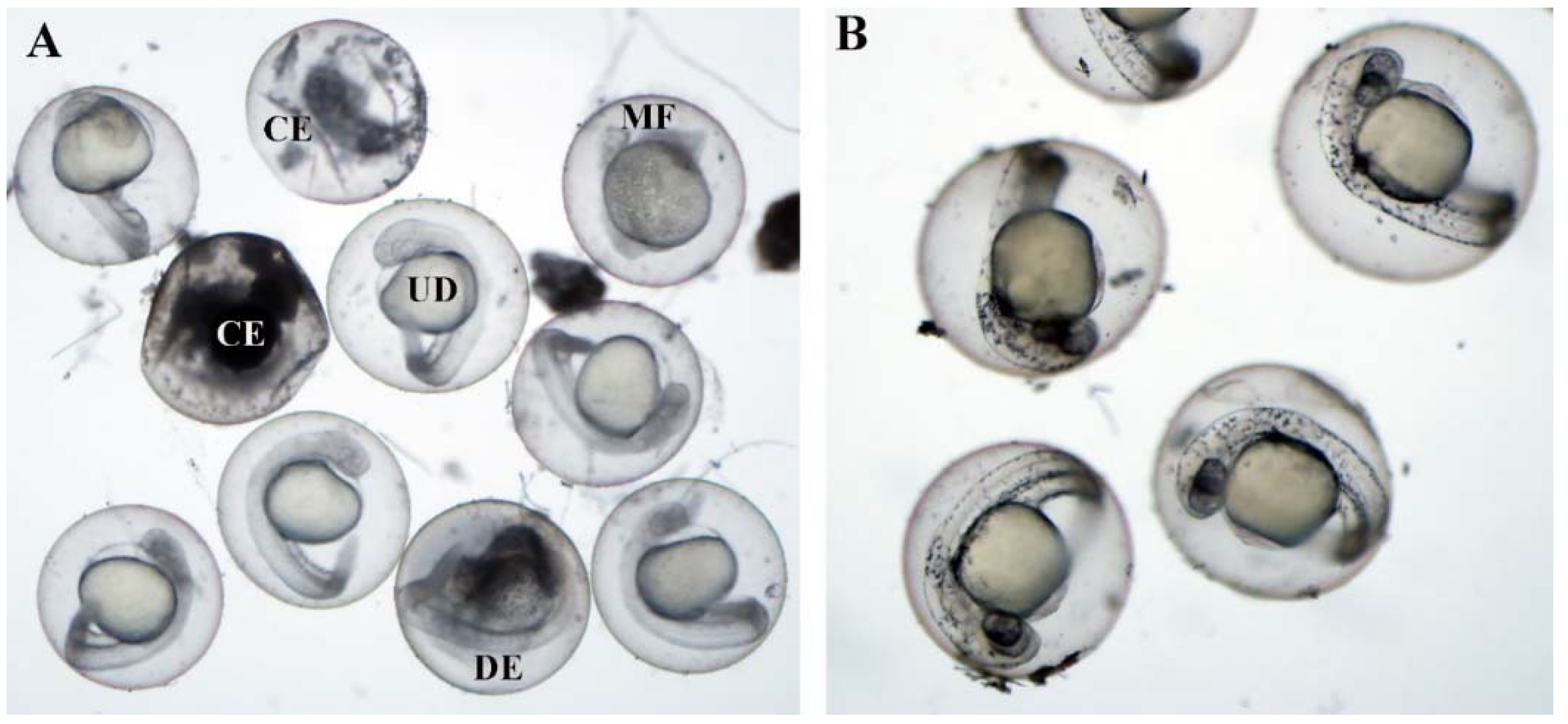

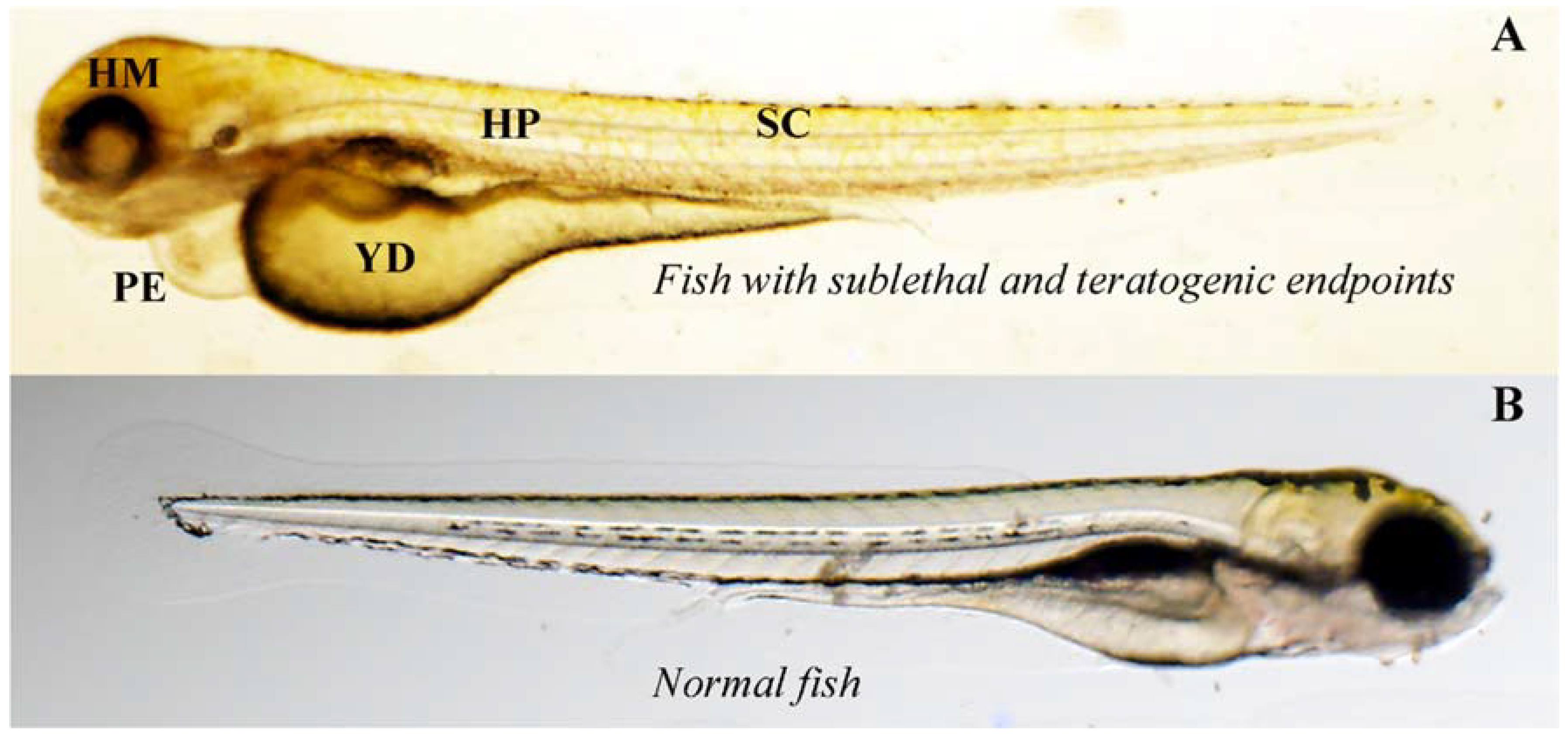

3. Results

Qualitative Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wohlers, T.; Gornet, T. History of Additive Manufacturing; Wohlers Associates, INC: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2014; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- 3D Printing Industry. 3D Printing Basics: The Free Beginner’s Guide. Available online: http://3dprintingindustry.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/3D-Printing-Guide.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2016).

- Alifui-Segbaya, F.; Williams, R.J.; George, R. Additive manufacturing: A novel method for fabricating cobalt-chromium removable partial denture frameworks. Eur. J. Prosthodont. Restor. Dent. 2017, 25, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stratasys. Safety Data Sheet (MED610). Available online: http://www.stratasys.com/materials/material-safety-data-sheets/polyjet/~/media/394dd5015bb6473496a19ea837881c25 (accessed on 30 November 2016).

- Stratasys. Printing Bio-Compatible Parts on Polyjet™ 3D Printers with MED620. Available online: http://usglobalimages.stratasys.com/Main/Files/SDS/MED620_Usage_Terms_1116.pdf?v=636160085940019299 (accessed on 18 January 2016).

- Alifui-Segbaya, F.; Varma, S.; Lieschke, G.J.; George, R. Biocompatibility of photopolymers in 3D printing. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2017, 4, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Test No. 236: Fish Embryo ACUTE Toxicity (FET) Test; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lieschke, G.J.; Currie, P.D. Animal models of human disease: Zebrafish swim into view. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007, 8, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Organization for Standardization. Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices—Part 2: Animal Welfare Requirements; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Directive 2010/63/eu of the european parliament and of the council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. Off. J. Eur. Union 2010, 53, 33–79. [Google Scholar]

- EnvisionTec GmBH. Advanced DLP for Superior 3D Printing. Available online: https://envisiontec.com/better3dprintingtechnology/ (accessed on 5 June 2018).

- Araújo, P.H.H.; Sayer, C.; Giudici, R.; Poço, J.G.R. Techniques for reducing residual monomer content in polymers: A review. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2002, 42, 1442–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EnvisionTec GmbH. E-shell 450: Safety Data Sheet. Available online: https://envisiontec.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/MK-SDS-EShell450Series-V20161114-FN-EN.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2018).

- EnvisionTec GmbH. E-Shell® 450 Series. Available online: https://envisiontec.com/3d-printing-materials/perfactory-materials/e-shell-450-series/ (accessed on 22 July 2017).

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 10993-5, Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices—Part 5: Tests for In Vitro Cytotoxicity; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel, R. Dart: The embryo test with the zebrafish danio rerio—A general model in ecotoxicology and toxicology. Altex-Altern. Tierexp. 2002, 19, 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lammer, E.; Carr, G.J.; Wendler, K.; Rawlings, J.M.; Belanger, S.E.; Braunbeck, T. Is the fish embryo toxicity test (FET) with the zebrafish (Danio rerio) a potential alternative for the fish acute toxicity test? Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2009, 149, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neves, C.B.; Lopes, L.P.; Ferrao, H.F.; Miranda, J.P.; Castro, M.F.; Bettencourt, A.F. Ethanol postpolymerization treatment for improving the biocompatibility of acrylic reline resins. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 485246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merck. Acrylic Monomers. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/materials-science/material-science-products.html?TablePage=16397884 (accessed on 3 December 2017).

- Decker, C. Photoinitiated crosslinking polymerisation. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1996, 21, 593–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 10993-1: Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices—Part 1: Evaluation and Testing within a Risk Management Process; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Autian, J. Structure-toxicity relationships of acrylic monomers. Environ. Health Perspect. 1975, 11, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geurtsen, W. Polymethylmethacrylate resins. In Biocompatibility of Dental Materials; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 255–270. [Google Scholar]

- Kanerva, L.; Estiander, T.; Jolanki, R.; Tarvainijn, K. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis caused by exposure to acrylates during work with dental prostheses. Contact Dermat. 1993, 28, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, T.J.; Witz, G. Structure-activity relationships in the hydrolysis of acrylate and methacrylate esters by carboxylesterase in vitro. Toxicology 1997, 116, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, G.N.; Lawrence, W.H.; Autian, J. Toxicological and pharmacological actions of methacrylate monomers i: Effects on isolated, perfused rabbit heart. J. Pharm. Sci. 1973, 62, 778–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mir, G.N.; Lawrence, W.H.; Autian, J. Toxicological and pharmacological actions of methacrylate monomers iii: Effects on respiratory and cardiovascular functions of anesthetized dogs. J. Pharm. Sci. 1974, 63, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DrugBank. Cyclomethicone 5. Available online: https://www.drugbank.ca/drugs/DB11244 (accessed on 18 June 2018).

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. Pubchem Compound Database. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 19 June 2018).

- Azimi, P.; Zhao, D.; Pouzet, C.; Crain, N.E.; Stephens, B. Emissions of ultrafine particles and volatile organic compounds from commercially available desktop three-dimensional printers with multiple filaments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 1260–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Cui, Y.; Qin, K.; Yu, J.; Guo, C.; Yang, J.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, D.; Wang, X. Synthesis and properties of a low-viscosity UV-curable oligomer for three-dimensional printing. Polym. Bull. 2016, 73, 571–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, A.; Cabral, J.T. Frontal conversion and uniformity in 3D printing by photopolymerisation. Materials 2016, 9, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Formlabs. Expanding 3D Printing Technologies to High-Volume Applications and Beyond; Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. Publishers: New Rochelle, NY, USA; pp. 1–53.

- Decker, C. Kinetic study and new applications of UV radiation curing. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2002, 23, 1067–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- eLABORATE. 3D Printer Marketplace; Joseph Allbeury: Cammeray, Australia, 2017; Volume 14, pp. 46–52. [Google Scholar]

| Manufacturing Parameters | Hazardous Ingredient(s) w/w % | Physical Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Photocured samples were built with Perfactory® DDP 4 M 3D printer. Manufacturing parameters are z-height: 67.98 mm, voxel: 100 µm and light power: 180 Mw/dm2. | 60–80% Proprietary methacrylate oligomers; 15–30% Proprietary methacrylate monomers; 1–2% diphenyl 2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl. | Flexural strength: 60–80 MPa; Flexural modulus: 1200–1500 MPa; Elongation at break: 2–4%; Tensile strength: 40–48 MPa; Tensile modulus: 2150–3250 MPa; Izod impact: 30 J/m; HDT: 75° at 1.82 MPa; Hardness, D Scale: 82–85; Viscosity: 320 cP at 30 °C. |

| 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | 96 h | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lethal endpoints | ||||

| Coagulation | . | . | . | . |

| Lack of somite formation | . | . | . | . |

| Non-detachment of tail-bud | . | . | . | . |

| Lack of heart-beat | . | . | . | . |

| Sublethal developmental endpoints | ||||

| Development of eyes | . | . | . | . |

| Spontaneous movement | . | . | . | . |

| Hypopigmentation | . | . | . | |

| Formation of edemata | . | . | . | |

| Endpoints of teratogenicity | ||||

| Spinal curvature and malformation of tail | . | . | . | . |

| Yolk deformation | . | . | . | . |

| Growth retardation | . | |||

| Non-Treated E-Shell 450 Methacrylate | Ethanol-Treated E-Shell 450 Methacrylate |

|---|---|

| 2-Hydroxyethyl methacrylate | Propylene glycol methyl ether |

| Propylene glycol methyl ether | m-Xylene |

| Octyl Acrylate | Methyl 3-methoxy-2-methylpropanoate |

| 2-Propyl-1-pentanol | Toluene |

| Benzaldehyde | Undecane |

| Tetrahydrofufuryl Butyrate | |

| Cyclohexanone | |

| Cyclomethicone 5 | |

| Cyclomethicone 6 | |

| 2,6,11-Trimethyldodecane | |

| Ethylbenzene | |

| N-[1-(4-Hydroxy-5-hydroxymethyltetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-4-oxo-1,4-dihydropyrimidin-2-yl]benzamide | |

| Texanol | |

| Methyl 3-methoxy-2-methylpropanoate | |

| Toluene | |

| Undecane |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alifui-Segbaya, F.; George, R. Biocompatibility of 3D-Printed Methacrylate for Hearing Devices. Inventions 2018, 3, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/inventions3030052

Alifui-Segbaya F, George R. Biocompatibility of 3D-Printed Methacrylate for Hearing Devices. Inventions. 2018; 3(3):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/inventions3030052

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlifui-Segbaya, Frank, and Roy George. 2018. "Biocompatibility of 3D-Printed Methacrylate for Hearing Devices" Inventions 3, no. 3: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/inventions3030052

APA StyleAlifui-Segbaya, F., & George, R. (2018). Biocompatibility of 3D-Printed Methacrylate for Hearing Devices. Inventions, 3(3), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/inventions3030052