1. Introduction

As climate change issues grow increasingly severe and carbon reduction strategies gain traction worldwide, the green and low-carbon transition of the transportation sector has become an inevitable focus. As a key component of urban public transport, buses are responsible for substantial carbon emissions, and advancing bus electrification has thus emerged as a pivotal task driving the green development of the transportation industry. Governments across the globe have rolled out a suite of supportive policies, including purchase subsidies, incentives for constructing charging infrastructure, and preferential road rights, which have markedly accelerated the deployment and adoption of battery-powered electric buses.

However, the transition from diesel buses to electric buses makes clear notable discrepancies in their technical and economic attributes. Constrained by the current limitations of battery technology, electric buses are generally plagued by shorter driving ranges and lengthier charging durations, which translate to lower daily operational hours and per-vehicle mileage compared to their traditional diesel counterparts [

1]. To uphold the original service frequency and operational standards, a straightforward one-to-one replacement is often inadequate, thus necessitating fleet size expansion. Crucially, the cost associated with replacing diesel with electric bus fleets is high [

2]. Consequently, optimizing the fleet size is imperative in order to strike a balance between operational demand and economic costs. Ignoring this issue could place public transport operators in a quandary, either having to compromise service quality due to insufficient vehicle capacity or shoulder considerable additional procurement and maintenance costs stemming from an oversized fleet.

Replacing diesel with electric buses affects multiple metrics, such as vehicle range, service capability, and operating costs, and must, therefore, be carefully evaluated to ensure both passenger demand and bus operators’ economic considerations are met. Heide et al. [

3] assessed different electric bus charging strategies in the Berlin bus network, finding that an electric bus fleet requires an increase of 2.1% to 7.1% in the number of vehicles compared to diesel buses. Moreover, different charging strategies lead to varying trade-offs among infrastructure requirements, fleet size, and operational efficiency. Sistig et al. [

4] evaluated the impact of full transport network electrification on the total cost of ownership and required number of vehicles. Their results showed that across all electric bus scenarios evaluated, the average cost and number of vehicles increased by 12% and 13%, respectively. Emiliano et al. [

5] studied optimal replacement strategies for diesel bus fleets with varying sizes, ages, maintenance costs, and emission rates. They proposed an integer programming model incorporating budget and environmental constraints, demonstrating that emission reductions can be achieved with a relatively low annual budget. Soltanpour et al. [

6] argued that a full transition from existing diesel to electric buses is both costly and time-consuming, and thus proposed a more feasible transitional approach combining diesel, hybrid, and electric buses, integrating consideration of charging infrastructure layout, fleet sizing, and operational scheduling.

The calculation of fleet size changes resulting from the replacement of diesel buses with electric ones requires careful consideration of route demand, vehicle performance, road infrastructure, and economic objectives. Rinaldi et al. [

7] employed a mixed-integer linear programming model to optimize fleet scheduling and examined the operational cost savings associated with electric and hybrid buses. Their findings revealed that marginal benefits gradually diminish as diesel buses are replaced by electric alternatives. In a study comparing lifecycle impacts, risks, and benefits across different powertrains, including diesel, hybrid, and electric buses, Harris et al. [

8] analyzed the effects of service frequency, capacity, range limitations, fleet size, and infrastructure configuration. El-Taweel et al. [

9] developed a framework for designing electric bus fleet sizing, aiming to determine the optimal number of electric buses and onboard battery capacity needed to fulfill a predefined schedule while supporting chargers of varying specifications. Their model accommodates both opportunity charging and depot charging strategies. Tian et al. [

10] applied a mixed-integer stochastic programming model to analyze fleet sizing for autonomous buses, demonstrating that the introduction of these vehicles not only substantially reduces the required fleet size but also helps control overall operating costs.

Electric bus charging and fleet sizing are directly related. The efficient operation of electric buses heavily relies on scientific charging scheduling strategies. An effective charging strategy not only ensures continuous vehicle operation but is also key to enhancing operational efficiency. Although numerous studies have focused on optimizing electric bus scheduling, they often operate under idealized assumptions, such as fixed or precisely predictable travel times between stops [

11]. In real urban road networks, traffic congestion significantly affects bus arrival times and energy consumption, thereby disrupting prearranged charging plans. Existing research seldom delves into the profound impact of varying levels of traffic congestion, a dynamic external factor, on charging optimization strategies. This oversight results in proposed strategies lacking adaptability and robustness in real-world, complex traffic environments, making them difficult to apply directly in practice.

Electric bus charging optimization is crucial for fleet sizing. Efficient charging strategies can reduce the number of vehicles required while ensuring operational services. Li et al. [

12] proposed a charging optimization model for electric bus networks which minimizes charging costs in a rapid-charging electric bus network through the coordinated optimization of bus services and charging schedules. To improve computational efficiency for large-scale networks, they developed an integrated algorithm combining adaptive large neighborhood search and branch-and-bound methods, applying it to a real bus network in Shenzhen, China. Bagherinezhad et al. [

13] introduced a model that optimizes electric bus spatiotemporal charging flexibility, achieving coordination between the charging timing and location within the bus system and the operation of the power distribution system under the constraints of both systems, validated using the bus system in Park City, USA. Bie et al. [

14] proposed an electric bus route scheduling method that accounts for the stochastic variability of travel time and energy consumption. They also introduced a strategy for charging during bus idle periods and analyzed the impact of randomness on departure times, idle duration, battery state of charge, and energy consumption per trip. Duan et al. [

15] optimized the scheduling and charging planning of electric buses, first developing an arc-based integrated model that minimizes total cost by considering grid stress costs, then reformulating it into a two-stage model and developing an efficient solution method. Xie et al. [

16] proposed a co-optimization model that develops vehicle schedules, charging plans, and driver assignments for electric bus routes, incorporating fast charging, slow charging, and battery swapping modes, conducting a real-world case study based on a bus route in Beijing, China.

Optimizing electric bus charging involves not only improving operational strategies but also coordinating vehicle configuration and charging infrastructure. Tzamakos et al. [

17] developed a model to optimize the deployment of fast wireless chargers in an electric bus network, accounting for delays caused by buses queuing for opportunity charging. They formulated an integer linear programming model to minimize the deployment cost of opportunity charging facilities. Wang et al. [

18] developed an integrated optimization model for charger deployment and fleet scheduling under opportunity charging. The model jointly optimizes battery capacity, fleet size, and charger deployment at stations and central hubs to minimize total annual cost, validated using a real-world case in Oslo, Norway. Liu et al. [

19] addressed the bus charging problem by optimizing the location of charging stations, the number of chargers, charging duration, and vehicle flow while considering power matching and seasonal factors, testing their optimization model on a bus route in Beijing, China. Wu et al. [

20] proposed a planning model for fast-charging station locations in an electric bus system, incorporating both the bus operation network and the power distribution network. Their goal was to minimize the total cost, including construction, operation and maintenance, travel cost to charging stations, and energy loss at charging stations built within bus hubs. Zhou et al. [

21] developed a comprehensive and robust planning model for electric bus systems by simultaneously optimizing the deployment of en route charging facilities, charging schedules, and battery configuration of electric buses to achieve total cost minimization.

Electric bus charging and fleet sizing are significantly influenced by seasonal variations. In high-latitude regions, low winter temperatures lead to reduced battery performance and a decreased driving range, resulting in longer average charging times and necessitating a larger fleet to maintain operational schedules. Under these conditions, the role of fast-charging technology in optimizing electric bus charging and fleet sizing becomes particularly important. When charging demand increases, fast-charging technology has the potential to enhance operational efficiency and reduce the number of vehicles required. Ambient temperature and charging rate have been proven to be directly relevant to electric bus operation [

22], though the discussion regarding their impacts on the electric fleet size configuration remains insufficient.

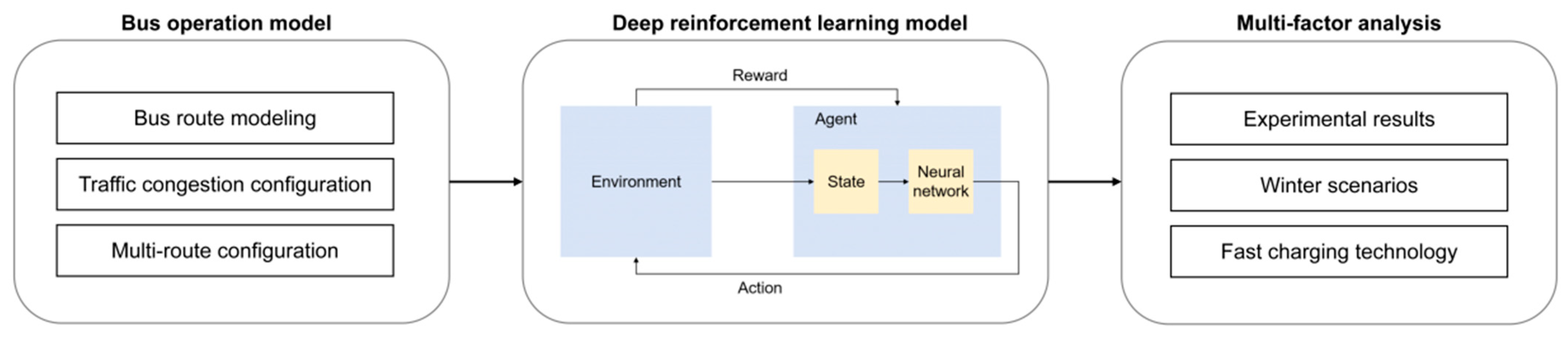

To address these challenges, this study employs a deep reinforcement learning (DRL) approach to optimize electric bus charging and fleet sizing. To ensure the research aligns with real-world traffic patterns and offers practical value, a simulation of Beijing Bus Route 400 was conducted using SUMO. The main innovations and contributions of this work are threefold: (1) We develop traffic-responsive electric bus charging optimization strategy to minimize charging time while maintaining sufficient energy for operational requirements. (2) We establish a comprehensive electric fleet sizing methodology suitable for both single-route and multiple-route operations. (3) We examine additional winter vehicle requirements, alongside the effects of fast-charging technology on electric bus charging and fleet sizing. A flowchart of this study is illustrated in

Figure 1.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bus Operation Model

A bus operation model is established where electric buses depart from the depot, complete one route trip, and return to the depot. Here, electric buses can only be charged at the depot and cannot undergo opportunistic charging during operation; therefore, each bus’s battery level must be sufficient to complete at least one trip before each departure. Under this constraint, electric buses should minimize charging time to improve operational efficiency. In the model, the charging facilities at the depot can meet the demands of the buses, ensuring that no queuing is required when charging is needed upon arrival, and all electric buses are of the same model, with identical performance parameters, including passenger capacity, battery capacity, and charging rate. The initial departure interval for the route is fixed. After the first electric bus completes its initial trip and returns to the depot, subsequent departure intervals are determined by the following buses’ arrival times. The charging rate is set as a constant value, meaning that charging amount and time have a linear relationship. Taking Beijing Bus Route 400 as an example, the route and bus parameters are shown in

Table 1.

Beijing Bus Route 400 is a vital public transport line with an annual operating mileage of approximately eight million kilometers, operating along the Fourth Ring Road of Beijing. The Fourth Ring Road plays a crucial role in diverting through-traffic from the core urban districts and connecting key functional zones within the city. During traffic congestion, its traffic density exceeds 60 vehicles per kilometer, reaching 160 vehicles per kilometer when at complete traffic standstill. Congestion mainly occurs during the morning and evening rush hours, each lasting about three hours. These conditions are similar to across major bus routes in Beijing. In congested traffic, diesel buses often remain idling for extended periods, leading to a surge in carbon emissions, with an extra carbon dioxide emitted, as well as extended emission of pollutants including carbon monoxide, hydrocarbons, and nitrogen oxides. Therefore, it is imperative to replace diesel buses with electric buses.

Electric buses’ electricity consumption rate is closely related to traffic flow density. To align the model with actual traffic flow variations throughout the day, different traffic flow densities were set for different time periods. The daily operation time for electric buses is from 5:00 to 22:00, totaling 17 h. To achieve a setting generally representative of weekday traffic flow, during morning and evening peak hours (7:00–10:00 and 17:00–20:00), the road traffic conditions were set as follows: on average, 50% of road segments were congested, and the other 50% were slow-moving. Specifically, the probability of both congested and slow-moving segments were set to 0.4–0.6. During transition periods between peak and off-peak hours (6:00–7:00, 10:00–11:00, 16:00–17:00, and 20:00–21:00), the traffic conditions were set to achieve, on average, 10% of road segments being congested, 80% slow-moving, and 10% free-flowing. Specifically, the probability of congested segments was 0–20%, slow-moving segments 70–90%, and free-flowing segments 0–20%. During off-peak hours (5:00–6:00, 11:00–16:00, and 21:00–22:00), the traffic conditions were set with an average of 10% of road segments being slow-moving and 90% free-flowing—a slow-moving probability of 0–20% and free-flowing probability of 80–100%. Congested, slow-moving, and free-flowing conditions correspond to traffic flow densities of 90 veh/km, 50 veh/km, and 10 veh/km, respectively. This setting is generally applicable to the traffic conditions on weekdays.

During operation, buses consume time when stopping at intermediate stations. In this study, this time is incorporated into operational buses’ total travel time. Specifically, when calculating buses’ average operating speeds, the time consumed due to stopping at intermediate stations is taken into account.

To establish the relationship between traffic flow density and electric bus electricity consumption rate under realistic scenarios, we first determine the correlation between traffic flow density and electric bus operating speed. Subsequently, based on the relationship between operating speed and electricity consumption rate, we derive the connection between traffic flow density and electricity consumption rate. Notably, the relationship between traffic flow density and electric bus operating speed is determined by actual route scenarios; therefore, to ensure the model aligns with real-world conditions, we simulated the operation of Beijing Bus Route 400 using SUMO. Meanwhile, the correlation between operating speed and electricity consumption rate is governed by vehicle and battery performance, and thus supported by empirical formulas from the existing literature.

2.2. Environment Modeling

The relationship between traffic flow density and bus speed was established across two steps using SUMO. First, the correlation between traffic flow density and speed (i.e., the speed of social vehicles) was constructed. Second, the relationship between social vehicle and bus speed was derived through regression analysis.

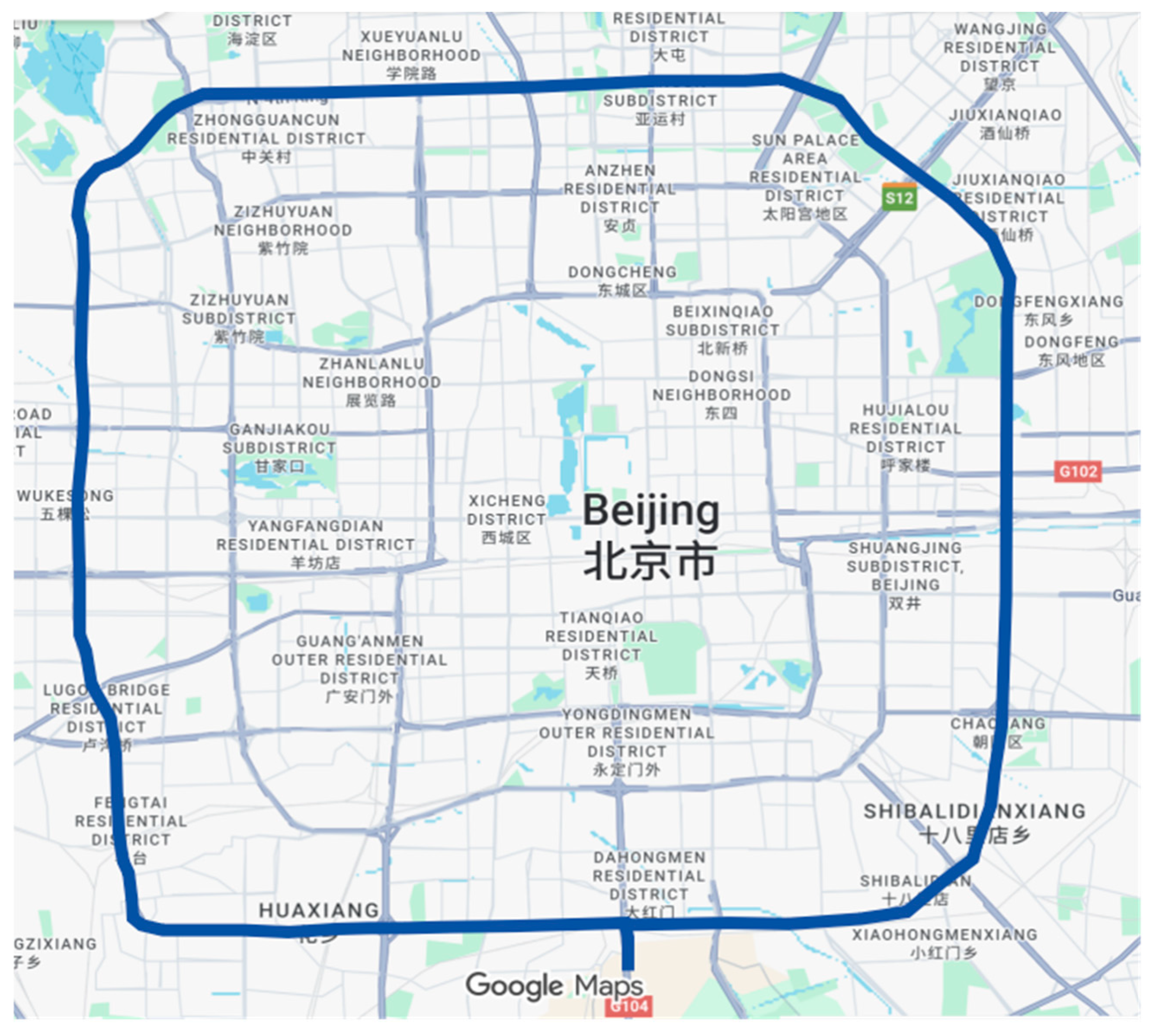

In SUMO, the road network was constructed and bus stops were configured using the NetEdit tool, with the scenario diagram shown in

Figure 2. Subsequently, both social vehicle and bus parameters were set, including acceleration, deceleration, vehicle length, and maximum speed, to align with real-world conditions, as shown in

Table 2. The driving randomness was set to 0.5, while all other parameters remained at their default values.

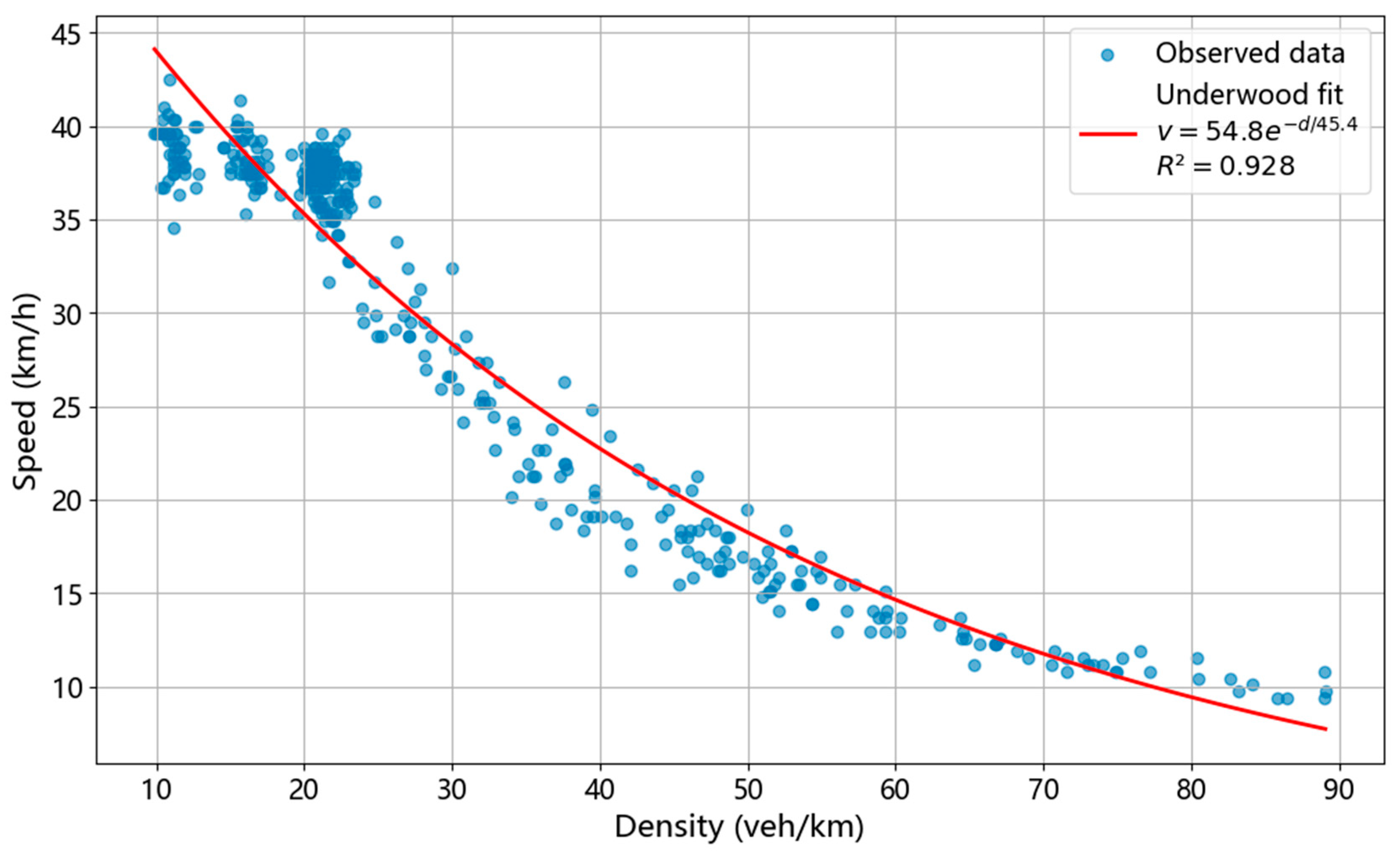

To minimize the random error of our data, nine independent experiments were conducted, collecting a total of 383 data sets, as shown in

Figure 3. Through co-simulation using Python 3.7 and SUMO 1.22.0, real-time traffic flow density and vehicle speed monitoring was implemented. This process generated multiple data sets correlating vehicle speed with different traffic flow density levels. The Underwood model was subsequently adopted to fit the relationship between traffic flow speed and density, and the resulting fitting function is presented in Equation (1).

where

is traffic flow speed and

is traffic flow density.

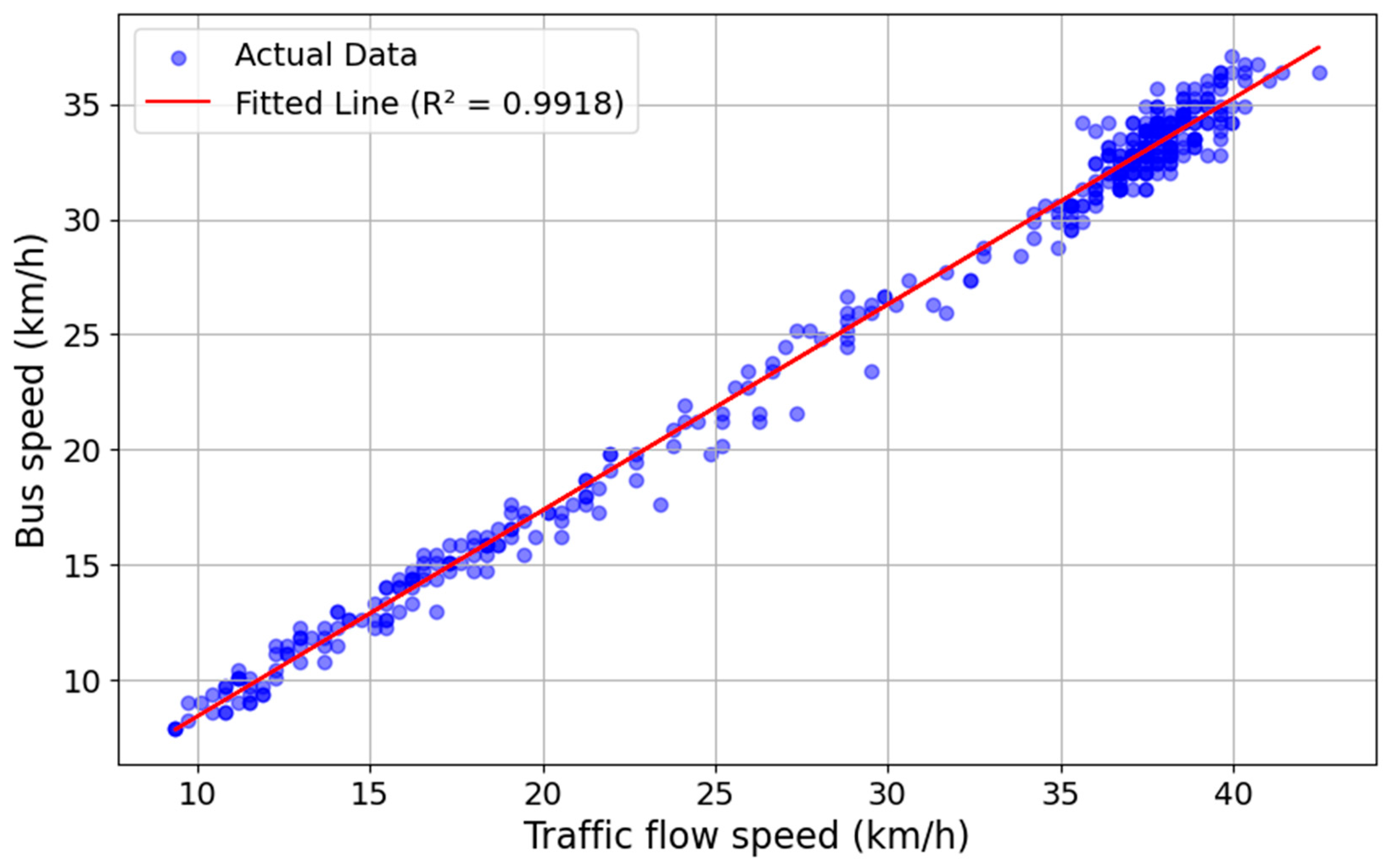

In real-world scenarios, buses and social vehicles typically operate in mixed traffic conditions, interacting with and influencing each other. Due to buses’ operational characteristics, such as frequent stops at stations, their travel speed is significantly lower than that of other vehicles, with the correspondence between traffic flow speed and bus speed illustrated in

Figure 4. Therefore, the relationship between bus and social vehicle speed was further fitted, and the resulting fitting function is presented in Equation (2).

where

is bus speed and

is traffic flow speed.

By combining Equations (1) and (2), the relationship between traffic flow density and bus speed is derived, presented as Equation (3).

where

is bus speed and

is traffic flow density.

Electric bus electricity consumption rate is closely correlated with their speed. Based on actual test data, reference [

23] fitted the relationship between bus speed and electricity consumption rate, as shown in Equation (4). Using Equations (3) and (4), electric bus electricity consumption per kilometer under a given traffic flow density can be calculated.

where

is electricity consumption rate and

is bus speed.

2.3. Deep Reinforcement Learning Model

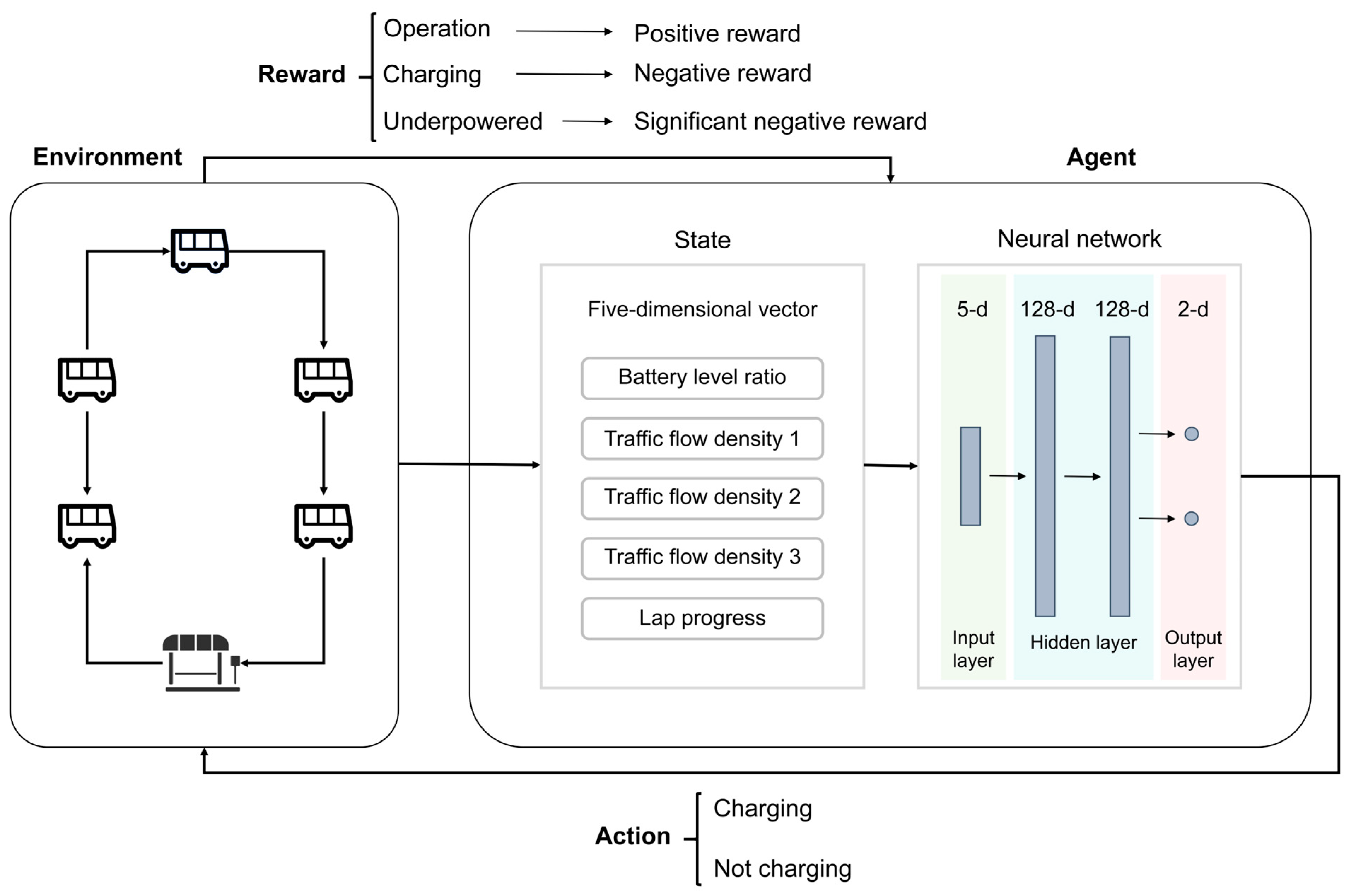

The DRL model is specifically designed to address the requirements of electric bus charging decision-making and route scheduling, with its overall design focusing on balancing decision accuracy, real-time performance, and adaptability to complex operational scenarios. The structure of the DRL model is illustrated in

Figure 5.

The DRL architecture adopted in this study was implemented based on the deep Q-network (DQN). This is because bus charging decision-making constitutes a binary discrete action space problem, and DQN is specifically designed to handle discrete actions by directly outputting the Q-values of limited actions. Compared with algorithms such as SAC (soft actor–critic) or PPO (proximal policy optimization), which are suited for continuous action spaces, DQN demonstrates greater directness and efficiency in such scenarios. Bus charging decision-making can be formulated as a binary action selection problem as the entire process is accomplished through a series of binary decisions. The interval between each decision is determined by the arrival intervals of buses at stations along the route. This formulation simplifies the problem while ensuring that charging duration is also optimized.

The model adopts a three-layer fully connected neural network to map operational states to optimal charging actions. The input layer is a normalized five-dimensional state vector, including battery level ratio, three traffic flow density distribution ratios, and lap progress. The battery level ratio eliminates training fluctuations from absolute battery differences and reflects endurance. The traffic flow density ratios are dynamically generated by time-period controllers to quantify congestion impacts. Lap progress provides a time reference for charging decisions. The hidden layers consist of two fully connected layers with 128 neurons each, using ReLU activation functions to introduce non-linear fitting capabilities and model complex state–action mappings. This two-layer design balances expressive power and efficiency, avoiding overfitting and meeting real-time scheduling needs. The output layer is a two-dimensional vector corresponding to action values (Q-values) for charging and not charging, with Q-values serving as the direct basis for the agent’s action selection. The forward propagation process is efficient: input vectors undergo linear transformations and activation processing in hidden layers before outputting Q-values, adapting to high-frequency decision-making in simulations.

To ensure stable convergence, the model integrates core DRL mechanisms tailored to bus scheduling. Action selection uses an epsilon-greedy strategy to balance exploration and exploitation. The exploration rate is initially high for full strategy exploration and linear decays to zero over episodes, ensuring stable late-stage decisions aligned with bus charging decision logic. The experience replay mechanism uses a large-capacity deque to store interaction samples, and when the buffer reaches the preset batch size, random sampling forms training batches. The target network delayed-update mechanism maintains two identical networks with asynchronous updates. The policy network undertakes real-time decision-making and parameter updates, whereas the target network furnishes stable Q-values and is synchronized with the policy network at preset intervals to preclude training oscillations. During batch training, the sampled data is first converted into an appropriate format and then transferred to the computing device for processing. The policy network calculates the current Q-values, while the target network computes the maximum Q-value corresponding to the next state. Subsequently, the target Q-value is derived using the Bellman equation. The mean squared error loss function is employed to quantify discrepancies between the predicted and target Q-values, and an adaptive optimizer updates the policy network weights through backpropagation, thereby facilitating faster convergence of the model.

The charging bus availability judgment function simulates a candidate vehicle’s operational state on the target route. It extracts the vehicle’s battery level ratio and the route’s traffic density ratio, resets lap progress, and constructs a five-dimensional state vector. The trained policy network outputs Q-values; if the optimal action is not charging, the vehicle is deemed available, enabling dynamic vehicle reuse and reducing idle waste and operational costs. The reward function balances avoiding operational interruptions and reducing charging costs with rewards and penalties. A high penalty is imposed for incomplete laps due to low battery, prioritizing service continuity. Base rewards are given for completing single laps, with penalties for unnecessary charging, guiding on-demand charging aligned with practical operations.

3. Results and Discussion

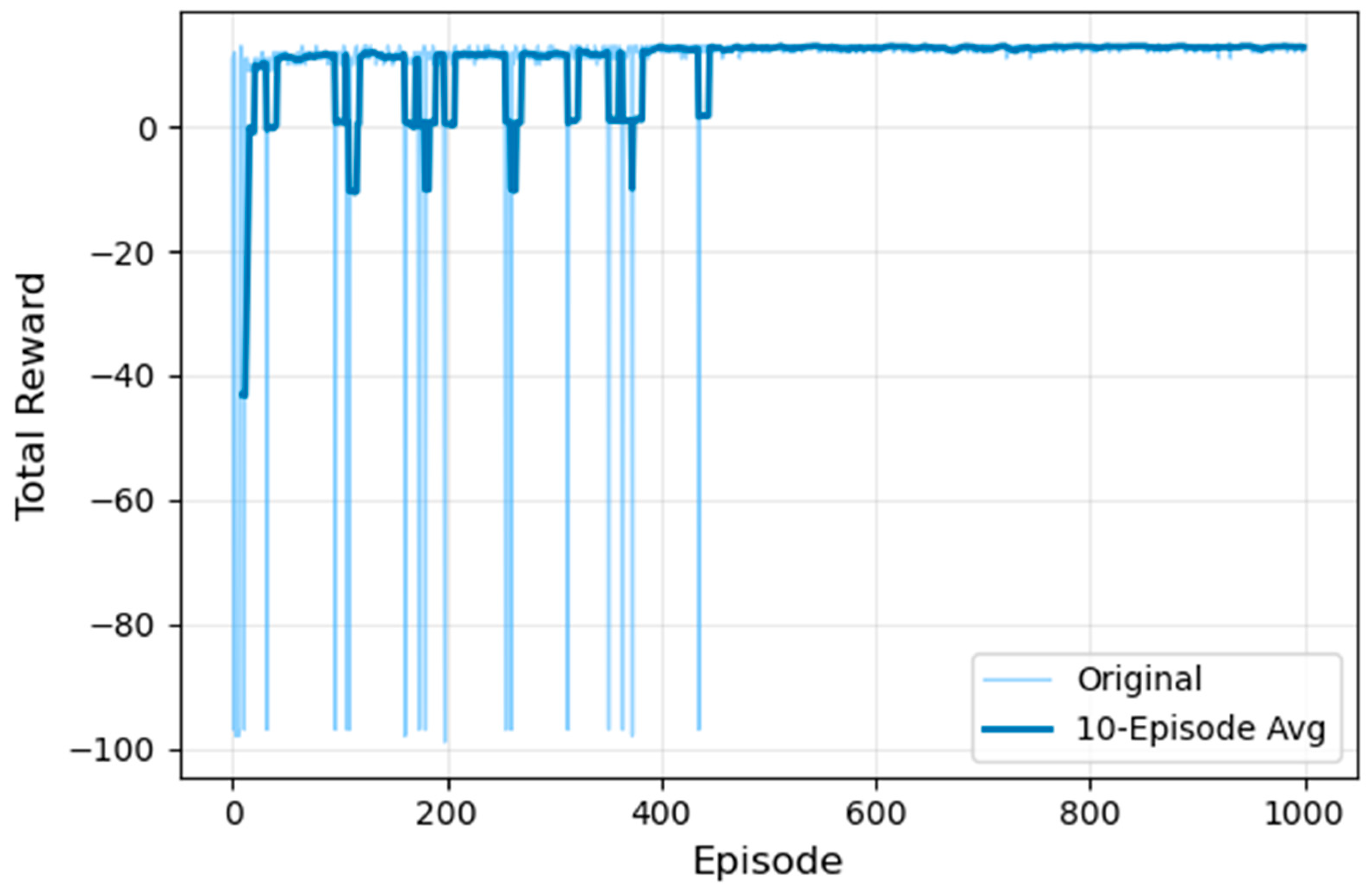

After training, the DRL model presented the optimal charging strategy for electric buses. This strategy possesses implicit characteristics, with the relationship between the environment and the strategy represented through a neural network. Its effectiveness is measured by maximizing the output value, which is the cumulative representation of the reward function. According to

Figure 6, during the training process, the reward function initially fluctuates and then stabilizes, showing an overall upward trend. In the first half of the training, due to a high exploration rate, the reward function exhibits significant fluctuations. In the second half of the training, the model no longer explores new strategies but instead learns from existing ones, causing the reward function to stabilize at a high level, indicating that the DRL model has effectively learned the electric bus charging strategy.

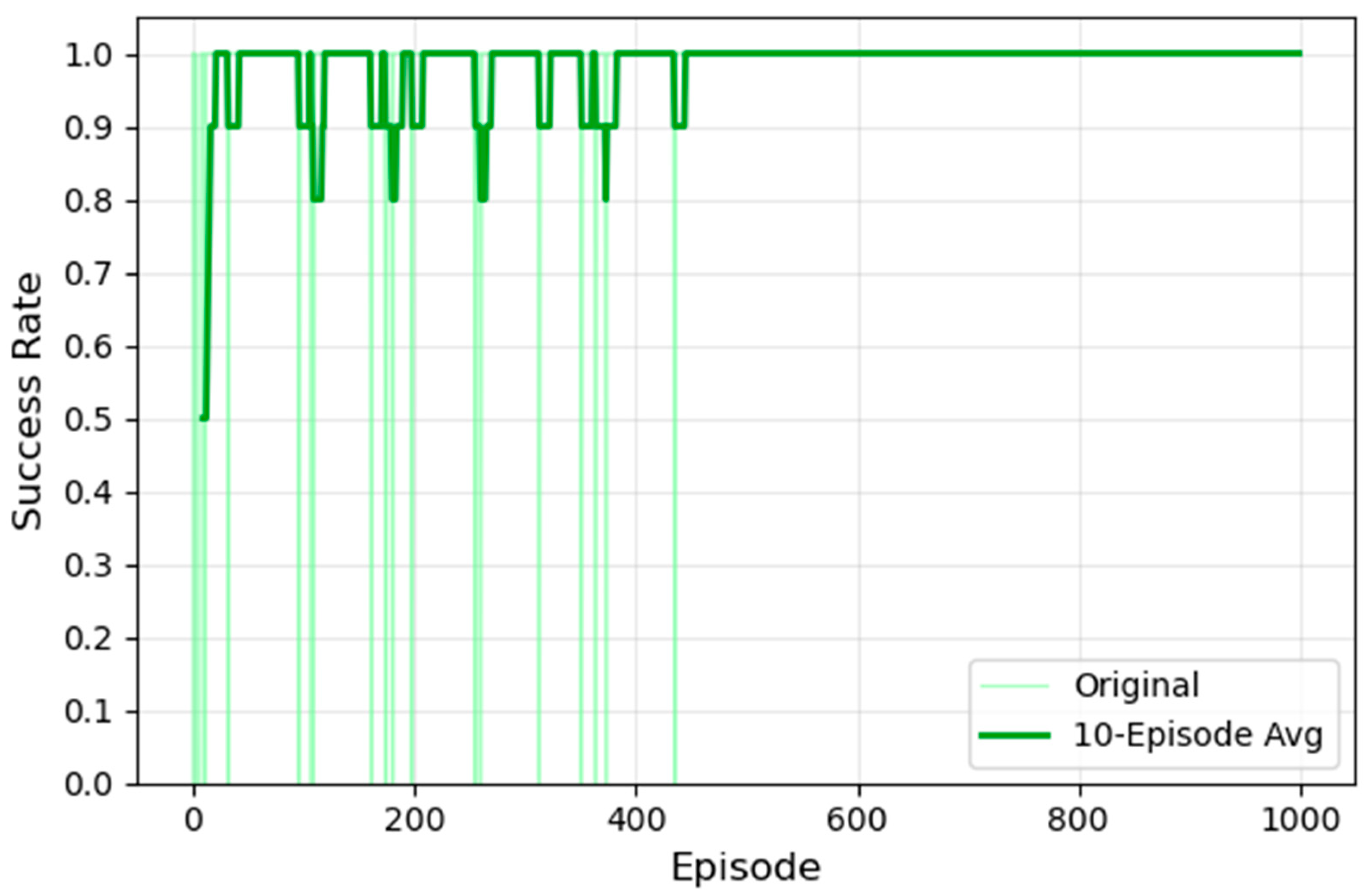

For electric bus operation, a key issue is to completely avoid mid-route power shortages, ensuring the successful completion of each trip. Therefore, it is necessary to statistically analyze the proportion of electric buses that successfully complete their trips. According to

Figure 7, in the first half of the training, the DRL model resulted in a small number of electric buses failing to complete their trips. However, in the second half of the training, perfect trip completion was achieved. This demonstrates that the DRL model’s charging strategy ensures efficient bus charging while avoiding mid-route power shortages.

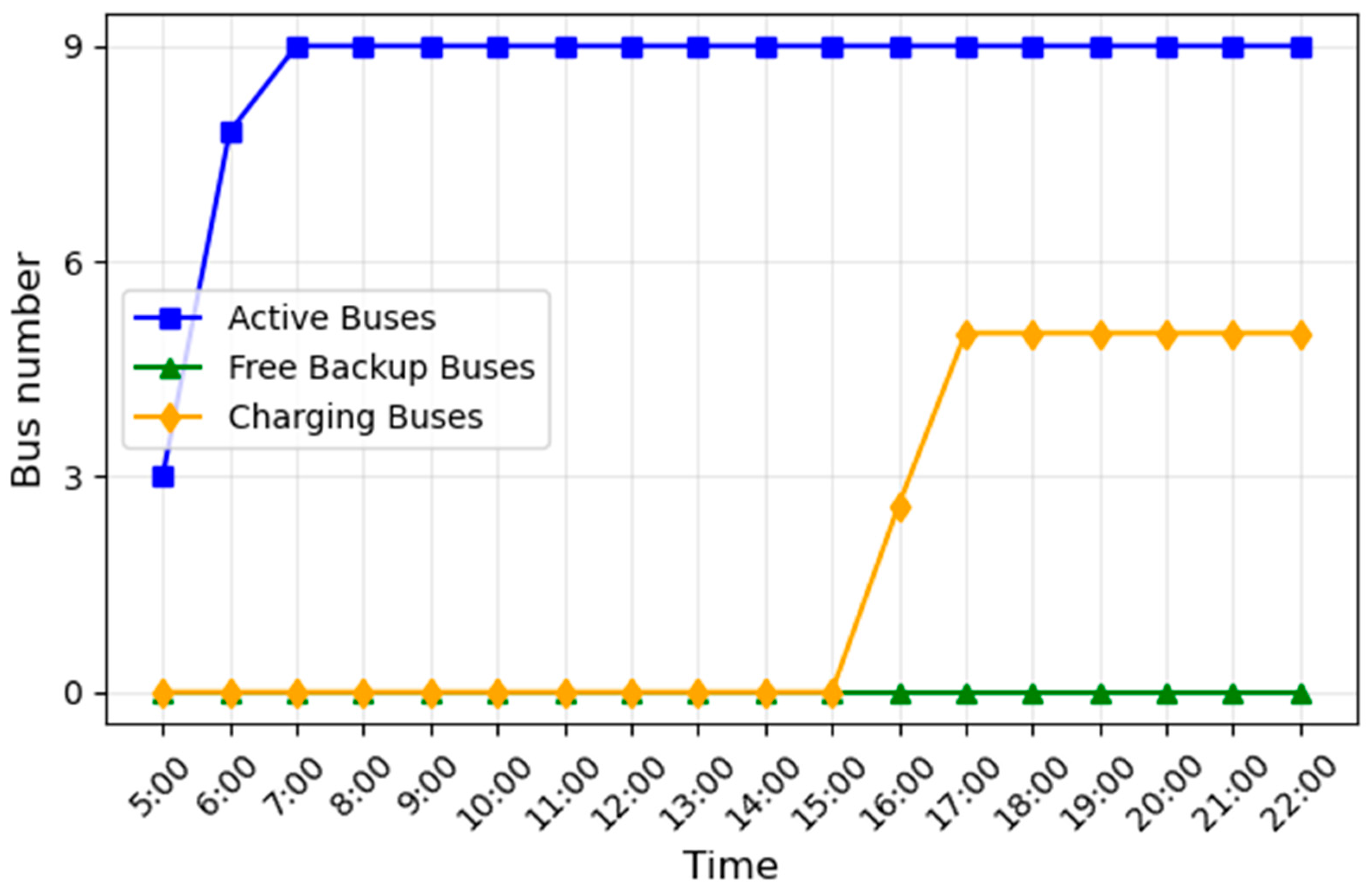

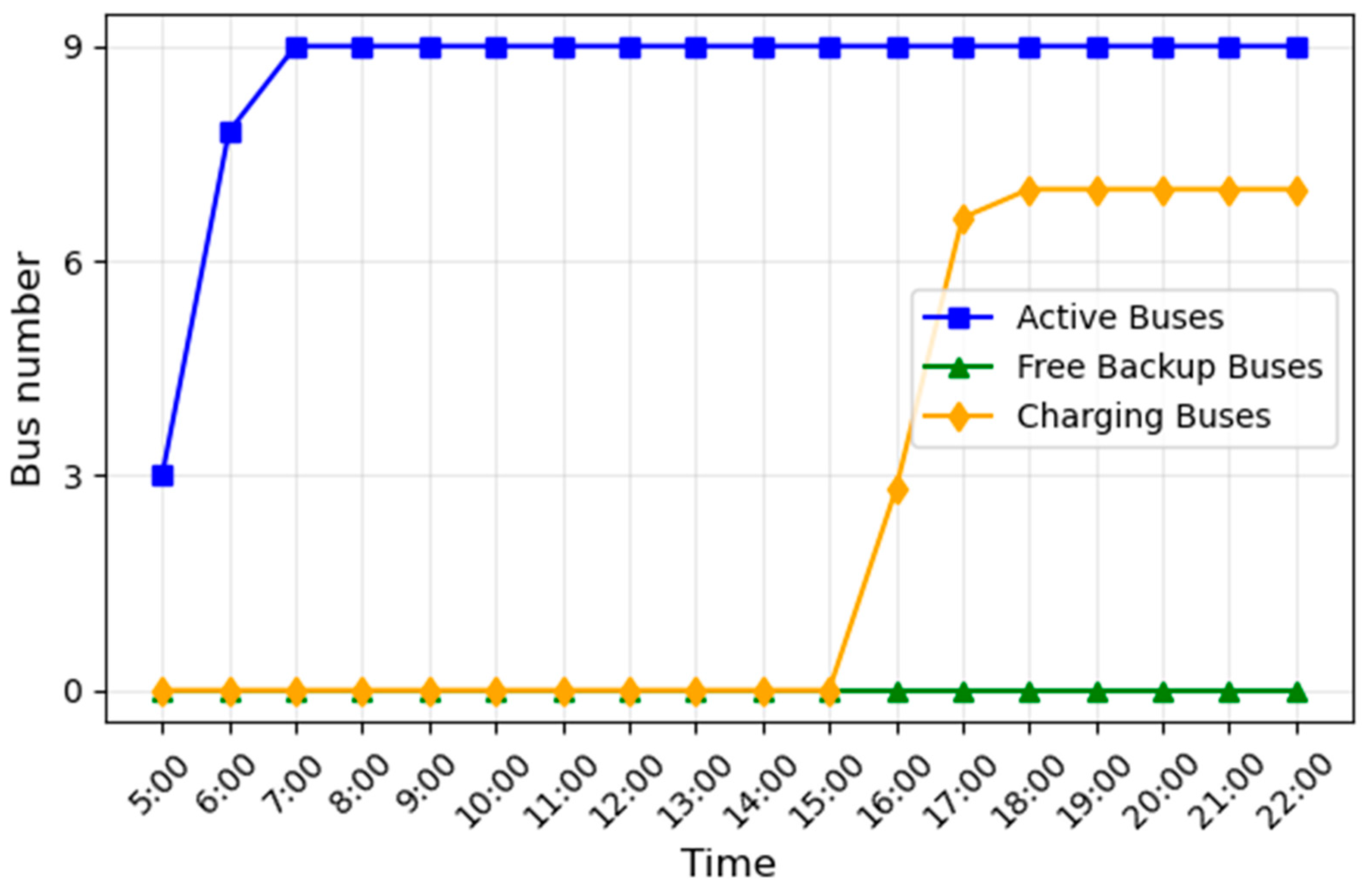

To validate the benefits of the proposed DRL bus charging strategy in terms of reducing fleet size, a comparison was made with the full-charging strategy. The comparison results are shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9. Under the DRL charging strategy, electric buses save charging time while ensuring that route operational demands are met. This results in the route requiring only five additional electric buses, saving two buses compared to the seven needed under the full-charging strategy.

Actually, a single bus station typically serves multiple bus routes. To discuss the configuration of electric bus fleet sizes under multi-route conditions, it was assumed that the station serves one, two, four, and eight routes, respectively, with each route having the same conditions as described earlier. Using the DRL and full-charging strategies, the resulting fleet sizes are shown in

Table 3. Compared to serving a single route, when a station serves two or more routes, the proportion of additional buses required by the DRL-based method is lower. In the case of an eight-route station, the original strategy required 72 diesel buses. With the DRL-based method, an additional 29 electric buses are needed, representing an increase of 40%. This is because when multiple routes share a single charging station, vehicles undergoing charging have more opportunities to be deployed to routes experiencing bus shortages, thereby reducing overall charging time and minimizing the total number of vehicles required.

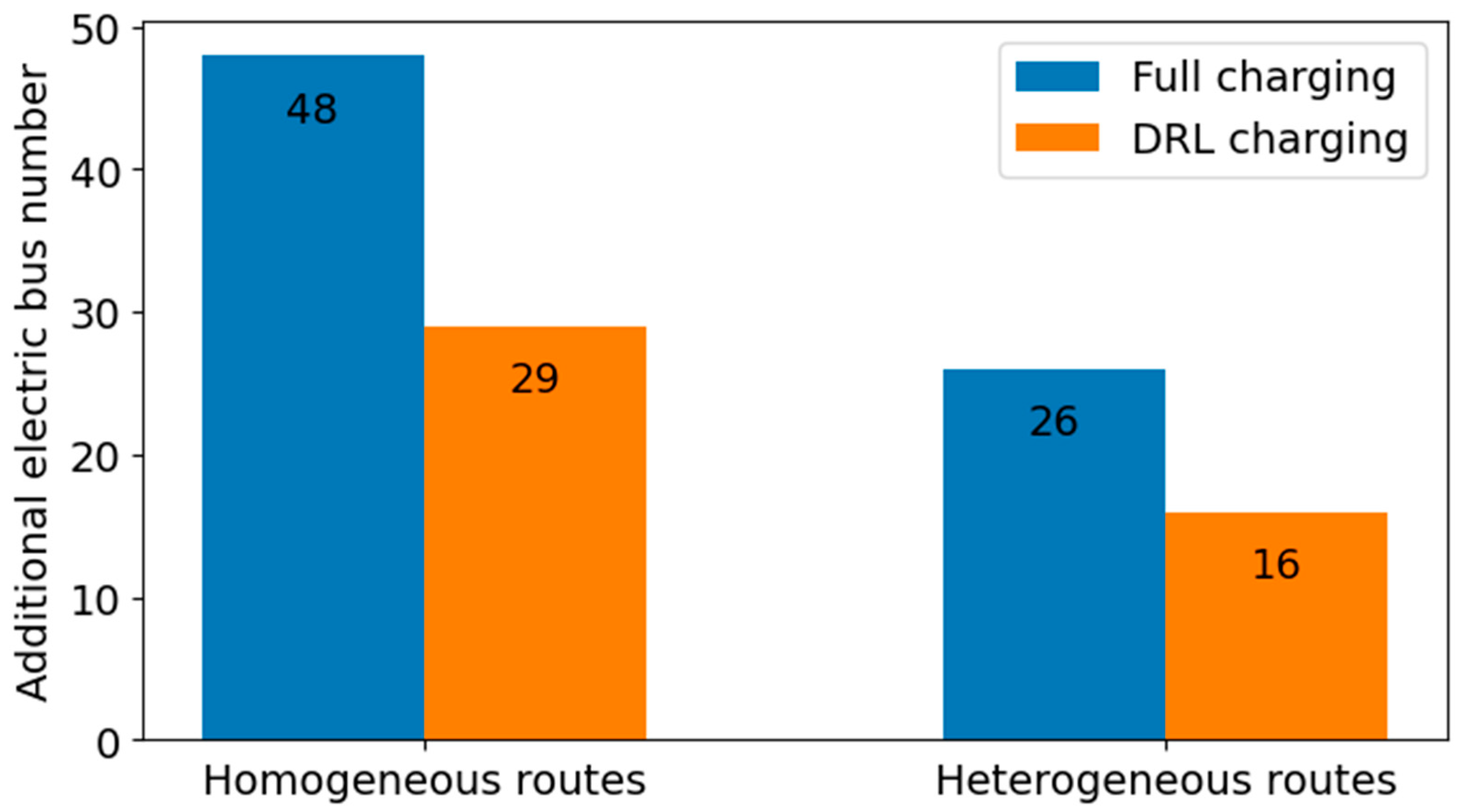

To verify the applicability of the proposed DRL model in more extensive scenarios, the model was applied to a heterogeneous route scenario, defined as follows: the charging station serves eight bus routes, among which four are identical to Beijing Bus Route 400, while the remaining four are 42 km long, with their other parameters kept unchanged. We compared the number of additional electric buses required under the full and DRL charging strategies in cases where the charging station provides service for eight routes (including both homogeneous and heterogeneous route configurations), as illustrated in

Figure 10. In the heterogeneous route scenario, compared with the full charging method, the proposed DRL method reduces the demand for electric buses by 10 units. This demonstrates that the strategy is applicable to both homogeneous and heterogeneous routes, thereby exhibiting excellent scalability.

Temperature has a significant impact on electric bus battery performance and electricity consumption rate. For inland cities at high latitudes like Beijing, winter temperatures are considerably lower than in other seasons, necessitating separate consideration of the effects of low temperatures on range and fleet sizing. The results of modeling assuming a 40% higher electricity consumption rate in winter compared to other seasons are shown in

Table 4. The demand for electric buses in winter significantly exceeds that in other seasons. Specifically, for a single route, an additional 8 vehicles are required in winter, accounting for 89% of the original fleet size, while in the case of eight routes, 46 additional vehicles are needed in winter, representing 64% of the original fleet size.

One of the key factors influencing the number of buses required for a route is electric bus charging speed. To analyze the impact of fast-charging technology on fleet size, a comparison was made between the conventional-charging and fast-charging of 150 kW, 300 kW, respectively, and the results are shown in

Table 5. Fast charging can significantly reduce the number of buses needed for a route. For a single route, fast-charging strategies require only 33% more buses, a notable decrease compared to the 56% required with conventional charging. In the case of eight routes, the 24% more buses needed with fast charging is also considerably lower than the 40% required with conventional charging.

We further validated the effectiveness of fast-charging technology in winter, and the results are presented in

Table 6. For a single route in winter, the number of additional vehicles required with fast charging increases by 56%, representing a significant reduction compared to the 89% increase when fast charging is not used. In an eight-route scenario, fast charging requires 42% more vehicles, while this value rises to 64% without fast charging, showing a distinct gap. Overall, the adoption of fast charging in winter can effectively reduce the number of additional vehicles needed, further underscoring the significance of fast-charging technology.

The comprehensive discussion of the above results reveals that the core of the DRL-based charging strategy, which reduces charging time and thus cuts down electric bus requirements, lies in terminating the charging process and switching vehicles back to operational status as soon as the battery is sufficiently charged to complete one trip. The proposed DRL model optimizes electric bus charging and fleet sizing under varying numbers of routes, different temperature conditions, and diverse charging rates, which verifies its robustness. Furthermore, the model exhibits high computational efficiency, with each optimization iteration taking less than three minutes.

4. Conclusions

This study aims to propose an optimized charging strategy for electric buses and calculate the fleet size required for them to replace diesel buses. Specifically, an electric bus operation model was developed based on a DRL approach, incorporating actual route characteristics and traffic congestion patterns. The conclusions are as follows:

1. The proposed method can minimize charging time while ensuring the completion of electric bus operations, thereby improving efficiency. The DRL algorithm demonstrated rapid and stable convergence.

2. In the examined case study, replacing diesel buses with electric buses required a 56% increase in the number of vehicles for a single route and a 40% increase for multiple routes. Using the DRL approach to manage charging reduced the number of buses required compared to the full-charging strategy.

3. Electric bus demand is significantly higher in winter, requiring a 64% increase in fleet size under multi-route operations. Adopting fast-charging technology can effectively reduce this electric bus demand.

This study holds certain implications for bus companies in terms of electric bus procurement and route operation. In particular, it incorporates practical factors such as traffic congestion, winter characteristics, and fast-charging technology and proposes a modeling and analysis method based on actual routes, thus demonstrating strong practical value.

This study also has several limitations. Firstly, all electric buses are assumed to be identical, with no consideration of heterogeneous fleets. Secondly, only one DRL model is utilized, and comparisons among different models were not performed. Furthermore, when discussing the impact of temperature, only one condition was analyzed, rather than multiple temperature scenarios throughout the year. Future research will further address these issues.