Abstract

Sexual consent is one of the most important tools used in the prevention of sexual violence, for which adolescents are especially vulnerable. However, it is unclear how sexual consent processes are defined and used by this population. To bridge this gap in knowledge, this scoping review sought to identify and synthesize the existing empirical research findings on sexual consent conceptualizations and processes among adolescents, as well as determine critical gaps in knowledge. Forty-three articles were reviewed following a systematic search of six academic databases. Articles were included if they were original empirical work published in English between January 1990 and March 2020, included adolescents aged 10 to 17 in their sample, and specifically studied sexual consent conceptualization, communication, and/or behavior. Seventeen articles, diverse in study design and geography, met these criteria and were analyzed. The findings suggest a propensity for adolescents to abstractly define sexual consent as verbal and direct in nature while simultaneously espousing indirect and non-verbal behavioral processes when presented with “real life” scenarios (e.g., vignettes, reflections on personal experience). In addition, the results reveal the significance of concepts like gender norms, normative refusals, and silence as key aspects of adolescent sexual consent. This review demonstrates that research on sexual consent among adolescents is highly limited overall, and the findings that are available indicate some concerning perceptions.

1. Introduction

As a result of differing theoretical, ideological, and methodological frameworks, there is a lack of consensus among researchers and theorists regarding the precise definition of sexual consent. Muehlenhard et al. [1] summarized the various representations of sexual consent found in the literature: “consent as an internal state of willingness, consent as an act of explicitly agreeing to something, and consent as behavior that someone else interprets as willingness” (p. 462). Whether sexual consent is an internal attitude, a verbal indication, or implied by behavioral cues continues to be contested, both in professional institutions and among the general public [1,2,3,4]. In spite of this dissensus, a definition from the Criminal Code of Canada [5] may be of use to the reader: “the voluntary agreement of the complainant to engage in the sexual activity in question”.

While there is no universally accepted definition, fundamental conceptualizations of sexual consent have been developed from the legal definition of sexual violence, namely, if sexual violence is “a sexual act that is committed or attempted by another person without freely given consent of the victim or against someone who is unable to consent or refuse”, then sexual consent is the determining factor between rape and “just sex” [3,6]. While this blunt differentiation has clear relevance for the legal system, it is misleading in that it purports a relatively straightforward, black and white process. Meanwhile, the literature indicates that a large range of sexual violations fall into a complex and ambiguous gray zone that is not adequately accounted for in this binary notion [2,7,8,9]. Contemporary social movements like #MeToo have raised awareness and furthered large-scale societal discourse about sexual consent and related issues, like the pervasive nature of sexual violence [8,10]. On the other hand, this movement has also uncovered widespread confusion, contention, and debate among the general public regarding what constitutes sexual consent.

If adults appear to struggle with the complexity of sexual consent, it is reasonable to assume that adolescents may experience even more difficulty understanding and navigating these processes, as they tend to have less sexual experience and knowledge relative to adults. Adolescence has long been identified as a critical developmental period for the exploration and initiation of dating, including sexual activity [11]. Biological changes associated with puberty, combined with changing peer groups and societal pressures of dating and intimacy, lead many early adolescents to begin exploring partnered sexual activity. The available literature demonstrates that a sizeable proportion of adolescents are sexually active—or have intentions to do so in the near future—and are therefore already engaging in the process of negotiating sexual consent, regardless of whether they have access to appropriate sex education or guidance [12,13,14,15]. These circumstances expose adolescents to the possibility of experiencing coercive, non-consensual, or even violent sexual interactions [13,16], which often result in detrimental health outcomes and trauma for survivors [17,18,19]. These adverse outcomes can persist over time, highlighting the need for early and relevant primary prevention programs. Furthermore, research indicates that when adolescents are sexually harmed, a substantial proportion are unlikely to disclose the experience to a trusted adult, exacerbating negative outcomes and preventing access to timely intervention [20,21,22,23,24].

Despite the importance of sexual consent to sexual violence prevention, it remains an understudied topic, particularly among the adolescent population. What we do know about sexual consent is based predominantly on research with undergraduate students and young adults, the vast majority of whom identify as heterosexual [1]. This research highlights that young adults tend to define sexual consent as a process involving mutual willingness, clear communication, and ongoing agreement; however, conceptualizations often vary based on gender, cultural background, and personal experience [1,25,26]. The evidence also suggests that both explicit (i.e., saying “yes”) and implicit or indirect communication strategies (e.g., body language) are used to conceptualize the consent process, although some express concern for the latter as it poses potential for ambiguity or miscommunication [27]. In practice, young adults often rely on non-verbal cues and contextual assumptions—rather than direct dialogue—to ascertain consent, in part due to the discomfort or disruption to intimacy involved [28,29,30].

There is, however, good reason to believe that adolescents and college-aged adults have distinct conceptualizations and processes of sexual consent as a result of their unique developmental stages, puberty, social norms, educational level, impressionability, knowledge, and experience with dating and sex [31,32]. As such, the adolescent age group would benefit from developmentally appropriate and targeted sexual consent education to build a foundation of healthy communication, ensuring high-quality and safe sexual experiences that persist into adulthood [12,32,33,34,35]. Furthermore, each person’s sense of sexual subjectivity—one’s identity as a sexual being—is formed during adolescence and has been shown to be heavily impacted by gender roles and stereotypes [36,37].

Relatedly, sexual scripts are also developed during this time. Theorized by Gagnon and Simon [38], sexual scripts are socially constructed templates for engaging in sexual behavior that allow people to draw from shared cultural understandings to accurately interpret meaning and respond in appropriate ways. Unfortunately, these scripts are often harmful and disempowering, especially for women [39]. Early adolescence is an ideal time to foster resilience and challenge damaging stereotypes before they become taken for granted norms.

Contemporary sex education curricula are heavily informed by miscommunication theory [3,27,40], which theorizes that coercive or non-consensual sex results from misunderstandings between men and women, “in which consent or non-consent is poorly communicated or inaccurately understood” [41]. This heteronormative framework was born out of Tannen’s [42] and Gray’s [43] popular positivist works about the “inherent” differences in language and communication between men and women. It has inspired popular prevention campaign slogans like “no means no” and “what part of the word ‘no’ do you not understand?” [44]. Furthermore, scholars have argued that increasingly popular affirmative consent standards—defined as an informed, unambiguous, enthusiastic, ongoing, and voluntary agreement to participate in a sexual act [45]—found in law and education are predicated on miscommunication theory [46,47].

A commonly cited miscommunication example is that men misinterpret or overestimate women’s desire to participate in a given sexual activity [40,48,49]. Affirmative consent policies attempt to resolve this issue by promoting the expression of sexual consent (or lack thereof) in clear, unambiguous, and verbally communicative ways [50]. Although admirable on its surface, this messaging is often implicitly directed toward girls and women [3,50,51,52]. As noted by Frith and Kitzinger [44], proponents advocate for “improved communication between the sexes”, but advice is commonly directed at “improving women’s communication skills, rather than men’s comprehension skills” (p. 520). Principles of miscommunication theory and affirmative consent fail to account for situations in which women do not feel able to verbalize “no” due to fear of escalated violence [44], social coercion (i.e., “the pressure to adhere to sex role obligations by individuals in an intimate relationship given the social and cultural expectations of their sexual roles,” [53], or emotional manipulation from their partners [40]. Recent conversation analysis of consent in contemporary media by Magnusson and Stevanovic [54] indicates that consent is portrayed as an interactional and embodied practice that need not be strictly unambiguous in order to be meaningful, contrary to the messages in affirmative consent models. Moreover, in most other social contexts, refusals are expressed less directly (e.g., pausing, making excuses, using prefaces, and making palliative statements) to save face or protect the other person’s feelings [50,55,56,57]. Furthermore, some studies have demonstrated that adolescents deem the strict use of verbal consent as unnatural and awkward, suggesting an incongruence between sex education programs and the real, everyday experiences of negotiating sexual consent [55,58,59].

Sex education and prevention efforts can be an important vehicle for changing sexual norms and outcomes. An enhanced understanding of how adolescents truly conceptualize and navigate sexual consent processes will improve the impact and reach of these programs. Rather than assuming that adolescents lack a basic understanding of sexual consent and communication due to their inexperience, it is important that curriculum developers identify their points of competency, as the relevancy of prevention programs relies on this information [27]. Cowling [60] also stresses the importance of sex education, building on participants’ existing knowledge and experiences. A clearer understanding of this issue from an adolescent perspective may facilitate knowledge translation and dissemination efforts so that sex education may better represent their lived reality.

As such, it is critical that we understand how adolescents define and navigate sexual consent processes. Furthermore, the first author’s extensive familiarity with the literature suggests that the evidence base is limited. Therefore, this scoping review study aimed to (1) identify the range, extent, and nature of existing empirical research; (2) synthesize the findings to issue an overview of sexual consent conceptualizations and processes among adolescents; and (3) determine the existing gaps to guide future research in this area [61]. An overarching research question guided this review: what is known from the existing literature about how sexual consent is defined and communicated by adolescents under the age of 18? In other words, this review sought to understand the “what” and “how” of sexual consent among members of this population.

2. Materials and Methods

This study adhered to the five-stage scoping review methodology developed by Arksey and O’Malley [62]. The review’s design was developed in advance of conducting the research and published in a detailed protocol (see [63]). The authors also followed the reporting guidelines delineated in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist to strengthen the methodological rigour of the review and adhere to reporting standards [64].

2.1. Search Strategy

In consultation with a university social sciences librarian, the authors developed a comprehensive search strategy involving several sources, including electronic databases and the hand searching of reference lists and key journals. Due to the multi-disciplinary nature of sexual consent, six databases spanning a range of disciplines were selected: Education Source, ERIC, Gender Studies Database, PsycINFO, Social Services Abstracts, and Sociological Abstracts. All searches were conducted by the first author on 22 March 2020. Search terms for the following three concepts were developed: adolescents (e.g., adolescent, youth, student, and teenager), sex (e.g., sexual activity, intercourse, and intimacy), and sexual consent (e.g., sexual consent, sexual communication, agreement, and sexual decision making) to create complex search strings that would satisfy the proposed research question. Search strategies were customized for each database and its particular field codes (see Table 1 for an example of the full electronic search strategy used for the PsycINFO database).

Table 1.

Search strategy used for PsycINFO database.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Per recommendations set out by Arksey and O’Malley [62] and Levac et al. [65], this scoping review implemented a broad and comprehensive approach to produce a breadth of coverage while also using clearly defined parameters for the study concepts and population. Articles were included if they met all of the following criteria: (1) original empirical work published between January 1990 and March 2020; (2) written in English; (3) study sample included school-age preadolescents and adolescents ages 10 to 17; (4) sexual consent conceptualization, communication, or behavior were the main focus of the study’s aims or findings. This time period was chosen due to increased public and research interest in sexual consent issues in the early 1990s following the publication of two best-selling books by Tannen [42] and Gray [43], which were central to legitimizing the miscommunication theory discussed above. In addition, mainstream and academic dialogue were generated following the US Senate Judiciary Committee’s [66] report that declared a “rape epidemic” in 1990 (p. 1). Regarding the sample age criteria, it is noted that if a range of adolescents and young adults were included in the study (e.g., 15 to 21 years), then the reported mean age must be below 18 years. All types of study designs and geographical locations were included. Peer-reviewed journal articles were prioritized, but related gray literature (e.g., government and community organization-authored reports) was also accepted. The following publication types were excluded: master’s or doctoral dissertations, commentaries, editorials, theoretical papers, books, or book reviews, as well as any articles not available online in full-text form.

2.3. Study Selection Process

Covidence, a web-based collaboration software program, was used for the organization and facilitation of study selection. For screening, the titles and abstracts of each article were first reviewed, followed by a full-text review. Both authors independently screened articles to determine whether they met the above-stated eligibility criteria and represented a “best fit” with the research question [62]. When discrepancies in decisions occurred, they met to discuss and resolve conflicts until full consensus was reached. This process resulted in a final list of articles to be included in the review.

2.4. Charting and Analysis

A data charting form was created in Microsoft Excel to extract and organize pertinent information from each article. Based on our research question and objectives, the following data were abstracted: authors, publication year, country (where the research was conducted), study aims, study design and methodology, sample size and characteristics (demographic information and recruitment details), and key findings specific to sexual consent. The abstracted data were then transferred into a summary table. Charting was conducted by both authors independently and then compared to confirm accuracy; any major discrepancies were discussed and resolved collaboratively until agreement was reached. These data constituted the basis of the analysis.

A descriptive numerical summary was also developed as an overview of the article characteristics and for comparison across studies. A qualitative thematic analysis was performed to identify recurrent themes across articles and produce a narrative account of the findings specific to sexual consent [65]. Qualitative analysis software NVivo v12 was used for the analysis [67]. Per the standard scoping review guidelines, no attempts will be made to assess the quality of individual studies [62].

2.5. Trustworthiness and Reflexivity

To ensure methodological rigour, this scoping review was guided by Lincoln and Guba’s [68] four criteria for trustworthiness: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. Credibility was strengthened via several strategies, including the use of multiple researchers for independent screening, charting, and coding; prolonged engagement with the data; negative case analysis; and triangulation. In addition, the scoping review process was guided by a pre-established protocol [63] to reduce the potential for bias or inconsistent practices. Transferability was addressed by providing detailed and contextualized information for each article, enabling the reader to assess the applicability of the review’s findings to other populations or settings. Clear and transparent reporting of the review process, as well as maintaining detailed documentation in an audit trail, supported the review’s dependability. Finally, confirmability was enhanced through peer debriefing; reflexive memoing; bracketing; and ongoing, critical self-reflection to increase awareness of the authors’ assumptions and subjectivities.

Given the socio-cultural complexity of this topic and the active role of the researcher in thematic analysis and interpretation, an author’s positionality statement is warranted. Both authors are social work researchers who identify as white, cisgender women and acknowledge the privileges and resources they are afforded, given their social location and access to resources. The first author has lived experience as a survivor of sexual violence, and both authors operate under feminist and social constructivist paradigms. These identities and values are relevant to this review, meaningfully informing various decisions and stages of the process. Continuous and critical reflexivity safeguarded the findings against unexamined assumptions, preconceptions, and biases.

3. Results

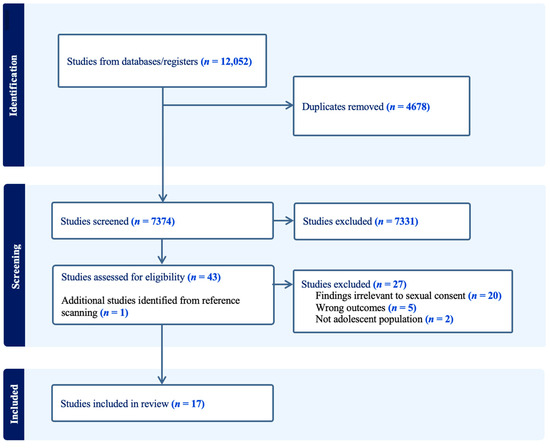

The six database searches returned 12,052 results, which were imported into Covidence. Of those, 4678 duplicates were identified and removed, resulting in a total of 7374 for title and abstract screening. A total of 7331 articles did not meet the eligibility criteria and were excluded, leaving 43 articles to be subjected to full-text review. A hand search of the reference lists from these 43 publications resulted in 1 additional article included in the full-text review. Initially, the authors independently reviewed the articles and followed the eligibility criteria strictly. However, one of the criteria—sexual consent conceptualization, communication, or behavior as the main focus of the study’s aims or findings—severely limited the final sample to only four articles [32,55,58,69]. After a discussion, it was determined that the authors would return to the full-text review stage and lower the threshold for criteria to include articles that incorporate some data relevant to sexual consent and the research question, despite it not being the main focus of these studies. Following this process, 17 articles were included for abstraction and analysis. It should be noted that two of these articles came from the same cross-sectional study [70,71]; however, since the analyses differed and produced varying results related to sexual consent, they were both included. See Figure 1 for the PRISMA-ScR flow diagram depicting the screening process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

As reported in Table 2, the majority of studies were qualitative (n = 10), conducted in the USA (n = 7) or the UK (n = 5), and published between 2011 and 2020 (n = 8). Table 3 provides additional detail regarding each study based on data abstraction and charting.

Table 2.

Overview of study characteristics.

Table 3.

Summary of reviewed studies.

3.1. Definitions and Conceptualizations

The first part of this study’s research question sought to understand how sexual consent was defined and conceptualized by adolescents. A total of 5 of the 17 included studies elicited participants’ sexual consent definitions abstractly (i.e., not in response to “real life” or applied scenarios like vignettes, reflecting on personal experiences, etc.). When participants explained sexual consent in these theoretical terms, they tended to employ terms like agreement, permission, approval, mutual, and voluntary [32,58,76,81]. They also endorsed the idea that sexual consent (or non-consent) should be communicated verbally, directly, and clearly. In Righi and colleagues’ [32] work, participants saw verbal consent as a relatively straightforward process and “the result of a spoken conversation, with most including ‘yes’, ‘no’, or ‘permission’ in the definition” (p. 9). For the participants in Hird’s [76] study, verbally expressing non-consent was necessary to prevent misunderstandings between men and women. These findings align with those reported in one of the quantitative studies, which showed that the majority of their sample believed a man can assume a woman wants to have sex when she “does not say no” [72]. However, an exception is noted in one study by Bindesbøl Holm Johansen and colleagues [55], who reported that their sample of young people (aged 16 to 19) described sexual consent as involving a range of non-verbal cues. These participants used the term “sensing” to represent situated bodily reciprocity, in which the other person expresses interest in sex by responding in kind (e.g., returning a kiss, touching the other person’s body, or removing clothes). In the absence of these signs, these adolescents indicated that they would then turn to verbal confirmation to verify that the other person would like to continue.

Another emergent theme regarding perceptions of sexual consent was that it was often understood in relation to the legal concept of rape, which was mentioned in eight articles. This was evidenced by the notion that rape is the absence of consent [58,75,76], or, similarly, that rape is someone proceeding beyond a verbal “no” [32,58,74,76,79]. For instance, two quotes from interviews with 17-year-olds illustrated these sentiments: “sex without consent I suppose that is rape” and “it’s all about permission because you can’t force someone to have sex with you, that’s rape” [58]. Furthermore, in order to prevent inadvertent rape or coercion, a teenage boy from Ott et al.’s [79] study had initiated consent conversations with his partner in advance of sexual activity to ensure that she would feel comfortable saying “no” to him. In a related vein, some participants reflected on past experiences of pressured and unwanted sex, likening their emotional responses to those of someone who had been raped despite not using the legal definition to label their experience [69,73].

3.2. Communication Strategies and Processes

Although the findings above show that sexual consent was indicated as being communicated via verbal and direct means, several studies also revealed that when discussing behavioral processes, adolescents relayed indirect and non-verbal strategies. This theme was present to some extent in all 17 of the articles and often emerged when researchers provided participants with a consent-related scenario (i.e., vignette) or asked participants to reflect on their past experiences. Some specific examples of these communication processes included conveying desires through mutual friends [77], mentioning or presenting contraception [71,75,79], making sexual jokes or “talking dirty” [71,79], and having conversations days in advance [34,77,79].

More generally, what emerged in the qualitative data was a more implicit and somatic-oriented approach to participants (1) ascertaining that their partner was consenting (or not) to sexual activity and (2) demonstrating to their partner that they were consenting (or not) to sexual activity. This approach can be summed up by the interpretation of body language, such as facial expressions, reciprocated intimacy, tensing up or freezing, removing clothing, touching, moving away, and other non-verbal cues. Since this process was less concrete or tangible than their definition of sexual consent, some of the authors reflected the adolescents’ difficulties in articulating it. A range of terms were employed by the participants: embodied communication strategies [69], “sensing” [55], a “presence” [34], being involved or “part of it” [58], and a “vibe” or “hunch” [32]. Adolescent boys from two of the articles were quoted as saying “people don’t really talk anymore, it’s more of a hands-on thing like if you move a certain direction like if you’re showing attention to the matter then that’s just enough” [32] and “you don’t need to ask, you can just feel it” [58].

Bindesbøl Holm Johansen and colleagues [55] identified “situated bodily reciprocity” (p. 8) as the reciprocation of certain actions (e.g., kissing back and taking the other’s clothing off) to indicate consent to sexual activity. In their sample, situated bodily reciprocity or “sensing” was the preferable option compared to verbal confirmation, which was considered awkward and even “a bit taboo” (p. 9). This sentiment was echoed by some of the young people in Whittington’s [81] study, who felt that explicit discussions about consent can “disrupt the flow” and “ruin the moment” (p. 211). A study using quantitative data supports these ideas, in which the majority of middle and high school students agreed that a man can expect sex from a woman if she “kissed, grabbed, or petted” him [72].

Another theme that emerged regarding consent communication and negotiation was the use of normative refusals, particularly among girls participating in the research. Normative refusals are discursive tools used in a range of everyday conversations to politely indicate one’s dissent so as to save face, protect the other person’s feelings, or otherwise prevent any negative consequences that might result from a direct “no” [57]. Examples of normative refusals might include delaying, making excuses or justifications, changing the subject, prefacing, and making palliative statements [57,82]. Normative refusals, in some form, appeared in nine of the articles. Most often, excuses were offered to show disinterest. As put by one girl in a focus group, “Then you kind of beat about the bush and say no. All the excuses you give are brushed aside and by the end you need more excuses” [55]. Despite some adolescents’ (mostly boys) assertion that verbal refusal is easy for girls [32,55,58], several of the findings reflected the immense difficulty and discomfort that girls experienced when refusing unwanted sex [58,69,73,80], evidenced by excerpts like “I didn’t want to hurt his feelings” [80] and “I didn’t want to make him feel bad” [73]. It should be noted that four of the articles described results that run counter to this theme, in which girls reported using a direct and verbal “no” to decline sexual activity [76,77,78,80].

A related theme, noted in seven of the papers, was the notion that silence was deemed a valid form of consent. In other words, the absence of refusal or dissent was seen as consent. This concept is concerning and again tended to be voiced by the boys in the study samples. The quantitative analyses revealed participants’ beliefs that desire for sex can be assumed if a woman “does not say no” [72], “just letting it happen” is an acceptable strategy to show your partner you want sex [71], and the absence of discussion represents clear communication between prospective partners [70]. The qualitative studies can help elucidate these results. For instance, the idea that “going along with it” was an implicit agreement to sex was found in Coy et al.’s [58] study; as stated by a 17-year-old boy, “if a girl didn’t want to, she would clearly state that…if they didn’t, most people would assume it was alright to carry on” (p. 60). Similar beliefs were noted in other research, even when excessive alcohol use was taken into consideration [74]. A related process was identified by the participants in Righi and colleagues’ [32] research, who stated that people—usually boys and men—initiate sexual activity to test their partner’s boundaries and see whether or not they outwardly object. If they did not, it was inferred that the other person was agreeing to continue. Furthermore, in the same study, the majority of participants (girls and boys) saw silence as evidence of sexual desire and enjoyment, with one girl asserting that “not saying anything, that probably means you like it” [32].

4. Discussion

As demonstrated in this review, the research regarding sexual consent among adolescents between 1990 and 2020 is highly limited, confirming the authors’ suspicions regarding the gap in empirical knowledge. Despite the application of an extensive search strategy and the authors’ choice to widen the inclusion criteria, only 17 articles (from 16 studies) were found. The studies were geographically diverse and relatively balanced in terms of research design (i.e., qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods). However, the findings indicate that, thus far, adolescent sexual consent research has been conducted through a heteronormative and cisgender lens, revealing a significant lack of understanding of queer, transgender, and non-binary voices and experiences.

The findings indicate that adolescents’ sexual consent definitions and conceptualizations were primarily expressed as a type of voluntary agreement made between two people, which is typically negotiated verbally and directly. However, a notable inconsistency was observed between these abstract constructs and the applied, behavioral practices that adolescents described, which were often framed as being indirect and non-verbal. Indeed, three articles [32,55,58] explicitly identified the co-existence of dual sexual consent notions that emerged from their data.

This contradiction between theory and practice may reflect the ubiquitous infusion of miscommunication theory and affirmative consent ideals in sex education, public health campaigns, news coverage, and feminist activism [83,84]. Rather than simply a reflection of reality, Frith and Kitzinger [44] hypothesized that the popularity of these principles is due to the social functions that they serve—namely, to provide women with (1) an illusory sense of control and empowerment in preventing sexual violence and (2) a way to rationalize their continued participation in heterosexual relationships. By believing that a coercive partner is unaware (but innocent and well-intentioned) and that future instances of sexual violence can be prevented by improving one’s communication, these objectives are accomplished. These hypothesized social functions have been corroborated in contemporary research, detailing the complex ways in which they provide girls and women with an illusory sense of safety and protection [40,85,86,87].

Both miscommunication theory and the affirmative consent standard risk perpetuating our heteropatriarchal culture by emphasizing individual behavior over the impact of broader systemic and structural factors, particularly the unequal distribution of power between men and women [2,44,88,89]. Therefore, adolescents’ description of sexual consent as verbal and direct may demonstrate their exposure to miscommunication discourse and the unconscious perpetuation of these social norms. Social desirability bias may have also played a role in participants’ responses, given that this messaging is what they have been taught and therefore what they “should” emulate.

On the other hand, the more nuanced behavioral perspective (that incorporates non-verbal and/or indirect approaches) expressed by participants may actually be closer to the lived realities of adolescents. It may also, to some degree, represent the behavioral processes modeled in mainstream media. Media sources, including movies, television, music, social media, and pornography, have been shown to be powerful socializing agents for adolescents [90,91,92]. Several content analyses have been conducted to examine the portrayal of sexual consent communication in a range of popular entertainment media, all of which reported that implicit and non-verbal cues were most frequently depicted compared to all other types [90,93,94,95,96]. Media conversation analysis by Magnusson and Stevanovic [54] revealed the depiction of complex and multi-modal interactional processes that combine verbal and embodied resources, suggesting that more nuanced and context-specific examples can be found in mainstream entertainment. Over time, exposure to these portrayals can be internalized by children and adolescents and become an important part of their developing sexual scripts.

Another interpretation of these results is that prevailing adolescent social norms emphasize several principles, including tact, tone perception, and non-verbal comprehension, as important in all kinds of conversations and negotiations [97]. As such, adolescents may instinctively apply these non-verbal communication standards to sexual consent. This theory is supported by some participants’ opinions that direct and/or verbal consent is awkward and unnatural. A byproduct of this phenomenon appears in another finding from this review, in which girls endorsed the use of normative refusals to convey non-consent. In everyday conversation, it is considered rude and unusual to issue a straightforward and direct “no” to any sort of offer or invitation [57]. As previously discussed, refusals are conveyed in much more nuanced ways, and it is reasonable to surmise that sexual refusals have higher stakes than those in other circumstances, especially for adolescents. Concerns of offending the other person, jeopardizing the relationship, or having their “no” not be respected are among the many reasons why many girls and women do not refuse verbally and directly [57,59]. Indeed, women’s preference for and use of normative refusals to decline sex has also been demonstrated in research with young adults [59,98,99,100]. Although there is some debate as to whether boys and men are capable of accurately interpreting normative refusals, the evidence generally suggests that they do possess the level of sophisticated comprehension required [48,52]. Some have argued that consent “misunderstandings” by men serve as justifications for sexual violence and coercion, allowing them to evade personal or legal accountability [52,57].

This review uncovered another unsettling belief among some adolescents that sexual consent may be assumed if the other person is silent or does not resist. The practice in which boys “test girls’ boundaries” by initiating sexual activity and waiting for an overt (often verbal) opposition was demonstrated in some of the findings. Consequently, the onus of sexual consent (and ultimately, whether sexual activity ensues) is placed on girls. As noted by Coy et al. [58], “young people understand what is meant by giving consent to sex, but have a very limited sense of what getting consent might involve”. This process is not reflective of an active and enthusiastic consent standard and epitomizes the traditional sexual script containing “gatekeeper” and “initiator” roles for women and men, respectively [2,101]. Boys are conditioned to actively, persistently, and even aggressively pursue sex with women, while girls are socialized to assume a passive role and either allow or resist men’s sexual advances [39]. There are several adverse implications of this script for both parties; namely, that women’s sexual agency is effectively eradicated, men’s consent becomes assumed and ever-present, and men’s responsibility to solicit and obtain consent is made obsolete [2,102]. These effects have clear consequences for heterosexual consent and are again echoed in studies with young adults [26,27,103].

Through an exhaustive review of the extant literature, our findings reveal not only a dearth of literature pertaining to adolescents’ conceptualizations of sexual consent but also that the research has focused almost entirely on heteronormative and gender-binary considerations. This review confirmed that empirical research is missing knowledge and evidence of consent and sexual scripts regarding same-sex relationships, as well as those of transgender and non-binary experiences. As research uncovered through the review tended to focus on Western and/or High-Income Country contexts, less is known about other cultural norms and trends regarding sexual consent and communication. Future research would benefit greatly from expanding the scope of identity-based group experiences to provide a more complex and diversified understanding of this issue.

4.1. Implications

There are several practice, policy, and research implications that emerge from these findings. First, practitioners working in sexual violence prevention and intervention can use these results to inform their work with adolescent survivors and perpetrators. Providing both groups with effective treatment requires an understanding of how adolescents conceptualize and practice sexual consent that is grounded in empirical research. This awareness can facilitate meaningful therapeutic discourse that challenges and shifts harmful social norms about consent, rape, and gender, encouraging resilience and behavioral change in adolescents. On the other hand, without this understanding, clinicians may inadvertently reinforce or uphold aspects of miscommunication theory and/or sexual scripts that further shield perpetrators and emphasize the victim’s role in their own sexual assault [86]. By the same token, these findings can be applied to sex education as a primary vehicle for shifting sexual norms and scripts as well as in the development of nuanced prevention programming based on sexual ethics versus the “yes/no” binary [56]. The conclusions derived from this review can provide educators and policymakers with a better sense of adolescents’ baseline knowledge and perspectives that can be expanded upon [60], ensuring that the content is relevant to their audience.

In-school sex education is long-form and offers the distinct advantage of time to explore these complex issues in detail [27]. However, sexual violence prevention in the form of awareness-raising campaigns can be more challenging. It is difficult to adequately convey the nuance of sexual consent in a short, pithy statement or a 30 s commercial, for instance [27]. That said, the findings from this study provide some insight into what language and messaging would be most effective for adolescents in order to improve the impact and reach of these campaigns and address the uncovered misconceptions—for example, a social media post that states, “This is what ‘no’ can look like” alongside graphics or brief video clips depicting non-consent in the form of non-verbal cues and normative refusals. Another example comes from the Sexual Assault Voices of Edmonton [104], which created posters with the statement, “Just because she isn’t saying no… doesn’t mean she’s saying yes.” Research that probes the impact of these and other sexual consent advisories may be beneficial and merits further exploration.

Overall, there is a clear need for more exploratory empirical research on this topic, since only four publications were found with a direct focus on sexual consent among adolescents. Future research should also examine and compare sexual consent processes among LGBTQ+ adolescents and those in same-sex relationships with heterosexual and cisgender adolescents, as there is an extreme paucity of data for this population; most of the extant sexual consent research assumes a heterosexual framework [105]. Research that has intersectionally explored such topics with regard to race, ethnicity, religion/spirituality, and cultural norms is also notably missing and could shed more nuanced light on these experiences as well as the internalized, culturally-rooted messaging to which young people are exposed. It would be interesting to examine whether and how the findings reviewed here would apply to a more diverse range of populations. There is also a lack of evaluation research regarding education programs that operate using miscommunication theory as their approach [3]. Critical evaluation of these programs could support advocacy efforts for more progressive programs that employ feminist principles and deconstruct gendered stereotypes. Finally, future studies (e.g., scoping reviews, meta-analyses) on this issue are important to extend and compare these findings beyond 2020. Given the widespread awareness of the #MeToo movement that saw global virality beginning in October 2017 [106] and the direct relevance of this movement to adolescents’ sexual consent understanding, this timeframe is critical to capture. Although this review’s end date of March 2020 likely preceded the majority of research examining the movement’s impact, it can serve as a valuable foundation to assess subsequent developments in this area.

4.2. Limitations

This study’s findings should be considered in light of some methodological limitations. First, the search only included articles published in English between January 1990 and March 2020, which may have led to the exclusion of relevant research published in other languages—limiting cross-cultural observations—or outside of this timeframe. Due to publication delays and resource constraints, the search was conducted and completed in March 2020, limiting the relevancy of the conclusions drawn to this time period. As noted above, important studies published in later years were excluded, including influential research sparked by the global #MeToo movement. Future research efforts to assess the impact of the #MeToo movement on adolescent sexual consent can use this study as a critical point of departure or baseline against which to measure change. Despite this shortcoming, this study contributes significantly to the field by offering a “snapshot” of three decades of synthesized data using broad and comprehensive search strategies (several sources, multiple disciplines, international studies, few exclusion criteria).

In addition, our search for gray literature was largely performed by hand-searching the reference lists of relevant articles—it is possible that less-cited or inaccessible reports were inadvertently omitted. Although the included articles were geographically diverse, most studies were conducted in Western societies and are therefore likely to denote culturally bound and limited perspectives. Relatedly, the results cannot be applied or generalized to other countries and cultures. Finally, due to the nature of a scoping review, the methodological quality of the studies was not evaluated. Systematic reviews that formally examine the quality of studies are recommended as future research efforts.

5. Conclusions

This review confirms that research regarding sexual consent, specifically among adolescents, is scant. In the literature that was identified, a range of potentially harmful inconsistencies were noted in adolescents’ definitions and conceptualizations of consent, in addition to how abstract constructs and communication approaches were applied in actual, real-life scenarios. There are opportunities—and arguably an onus—for future research, intervention development and evaluation, and comprehensive sex education to focus more specifically on adolescents, as well as to diversify the consideration of such topics beyond heteronormative, cisgender, gender-binary, and Western notions of sexual norms and practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.O. and S.B.; methodology, C.O. and S.B.; formal analysis, C.O. and S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, C.O. and S.B.; writing—review and editing, C.O.; project administration, C.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries or requests can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews. |

References

- Muehlenhard, C.L.; Humphreys, T.P.; Jozkowski, K.N.; Peterson, Z.D. The complexities of sexual consent among college students: A conceptual and empirical review. J. Sex. Res. 2016, 53, 457–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beres, M.A. Spontaneous’ sexual consent: An analysis of sexual consent literature. Fem. Psychol. 2007, 17, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenner, L. Sexual consent as a scientific subject: A literature review. Am. J. Sex. Educ. 2017, 12, 451–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, S.E.; Muehlenhard, C.L. “By the semi-mystical appearance of a condom”: How young women and men communicate sexual consent in heterosexual situations. J. Sex. Res. 1999, 36, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criminal Code; 2024; Volume 273.1. Available online: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-46/page-38.html (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Gavey, N. Just Sex? The Cultural Scaffolding of Rape; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarsson, L. “Excuse me, but are you raping me now?” Discourse and experience in (the grey areas of) sexual violence. NORA Nord. J. Fem. Gend. Res. 2018, 26, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindes, S.; Fileborn, B. “Girl power gone wrong”: #MeToo, Aziz Ansari, and media reporting of (grey area) sexual violence. Fem. Media Stud. 2020, 20, 639–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, T.P. Understanding Sexual Consent: An Empirical Investigation of the Normative Script for Young Heterosexual Adults. In Making Sense of Sexual Consent; Cowling, M., Reynolds, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 209–225. [Google Scholar]

- Alaggia, R.; Wang, S. “I never told anyone until the #metoo movement”: What can we learn from sexual abuse and sexual assault disclosures made through social media? Child. Abus. Negl. 2020, 103, 104312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E.H. Identity: Youth and Crisis; W.W. Norton & Co.: Oxford, UK, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Javidi, H.; Maheux, A.J.; Widman, L.; Kamke, K.; Choukas-Bradley, S.; Peterson, Z.D. Understanding adolescents’ attitudes toward affirmative consent. J. Sex. Res. 2020, 57, 1100–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kann, L.; McManus, T.; Harris, W.A.; Shanklin, S.L.; Flint, K.H.; Queen, B.; Lowry, R.; Chyen, D.; Whittle, L.; Thornton, J.; et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2018, 67, 1–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, C.; Smith, A.; Saewyc, E.; McCreary Centre Society. Sexual Health of Youth in BC; McCreary Centre Society: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Widman, L.; Golin, C.E.; Kamke, K.; Burnette, J.L.; Prinstein, M.J. Sexual assertiveness skills and sexual decision-making in adolescent girls: Randomized controlled trial of an online program. Am. J. Public. Health 2018, 108, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, G.; Copen, C.E.; Abma, J.C. Teenagers in the United States: Sexual activity, contraceptive use, and childbearing, 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. Vital Health Stat. 2011, 23, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin, E.R.; Menon, S.V.; Bystrynski, J.; Allen, N.E. Sexual assault victimization and psychopathology: A review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 56, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedtke, K.A.; Ruggiero, K.J.; Fitzgerald, M.M.; Zinzow, H.M.; Saunders, B.E.; Resnick, H.S.; Kilpatrick, D.G. A longitudinal investigation of interpersonal violence in relation to mental health and substance use. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 76, 633–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, K.; Sher, L. Dating violence and suicidal behavior in adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2013, 25, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broman-Fulks, J.J.; Ruggiero, K.J.; Hanson, R.F.; Smith, D.W.; Resnick, H.S.; Kilpatrick, D.G.; Saunders, B.E. Sexual assault disclosure in relation to adolescent mental health: Results from the National Survey of Adolescents. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 2007, 36, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogan, S.M. Disclosing unwanted sexual experiences: Results from a national sample of adolescent women. Child. Abus. Negl. 2004, 28, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishna, F.; Alaggia, R. Weighing the risks: A child’s decision to disclose peer victimization. Child. Sch. 2005, 27, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofziger, S.; Stein, R.E. To tell or not to tell: Lifestyle impacts on whether adolescents tell about violent victimization. Violence Vict. 2006, 21, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telljohann, S.K.; Price, J.H.; Summers, J.; Everett, S.A.; Casler, S. High school students’ perceptions of nonconsensual sexual activity. J. Sch. Health 1995, 65, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyadike-Danes, N.; Reynolds, M.; Armour, C.; Lagdon, S. Defining and measuring sexual consent within the context of university students’ unwanted and nonconsensual sexual experiences: A systematic literature review. Trauma. Violence Abus. 2024, 25, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jozkowski, K.N.; Peterson, Z.D. College students and sexual consent: Unique insights. J. Sex. Res. 2013, 50, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beres, M.A. Rethinking the concept of consent for anti-sexual violence activism and education. Fem. Psychol. 2014, 24, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, T.P. Perceptions of sexual consent: The impact of relationship history and gender. J. Sex. Res. 2007, 44, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jozkowski, K.N.; Sanders, S.; Peterson, Z.D.; Dennis, B.; Reece, M. Consenting to sexual activity: The development and psychometric assessment of dual measures of consent. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2014, 43, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rittenhour, K.; Sauder, M. Identifying the impact of sexual scripts on consent negotiations. J. Sex. Res. 2024, 61, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, F.S.; McKenney, S.J.; Poulsen, F.O. Early adolescents’ “crushing”: Pursuing romantic interest on a social stage. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2016, 33, 515–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righi, M.K.; Bogen, K.W.; Kuo, C.; Orchowski, L.M. A qualitative analysis of beliefs about sexual consent among high school students. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP8290–NP8316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamke, K.; Stewart, J.; Widman, L. Adolescent Girls’ Attitudes about Sexual Consent as a Function of Gender Norms; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319042651_Adolescent_Girls'_Attitudes_about_Sexual_Consent_as_a_Function_of_Gender_Norms (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Michels, T.M.; Kropp, R.Y.; Eyre, S.L.; Halpern-Felsher, B.L. Initiating sexual experiences: How do young adolescents make decisions regarding early sexual activity? J. Res. Adolesc. 2005, 15, 583–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E. Prevention of and interventions for dating and sexual violence in adolescence. Pediatr. Clin. North. Am. 2017, 64, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquette, M.-M.; Dion, J.; Bőthe, B.; O’Sullivan, L.F.; Perrier Léonard, D.; Bergeron, S. How does sexual subjectivity vary on the basis of gender and sexual orientation? Validation of the short Sexual Subjectivity Inventory (SSSI-11) in cisgender, heterosexual and sexual and gender minority adolescents. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2024, 53, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolman, D.L. Dilemmas of Desire: Teenage Girls Talk about Sexuality; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon, J.H.; Simon, W. Sexual Conduct: The Social Sources of Human Sexuality; Aldine Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Wiederman, M.W. The gendered nature of sexual scripts. Fam. J. 2005, 13, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkett, M.; Hamilton, K. Postfeminist sexual agency: Young women’s negotiations of sexual consent. Sexualities 2012, 15, 815–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frith, H. Sexual Scripts, Sexual Refusals and Rape. In Rape: Challenging Contemporary Thinking; Horvath, M., Brown, J., Eds.; Willan Publishing: Devon, UK, 2009; pp. 99–122. [Google Scholar]

- Tannen, D. You Just Don’t Understand: Women and Men in Conversation, 1st ed.; William Morrow Paperbacks: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, J. Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus: The Classic Guide to Understanding the Opposite Sex, Reprint ed.; Harper Paperbacks: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Frith, H.; Kitzinger, C. Talk about sexual miscommunication. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 1997, 20, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherstone, L.; Byrnes, C.; Maturi, J.; Minto, K.; Mickelburgh, R.; Donaghy, P. What is Affirmative Consent? In The Limits of Consent: Sexual Assault and Affirmative Consent; Featherstone, L., Byrnes, C., Maturi, J., Minto, K., Mickelburgh, R., Donaghy, P., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jozkowski, K.N. Barriers to affirmative consent policies and the need for affirmative sexuality. Univ. Pac. Law. Rev. 2016, 47, 741. [Google Scholar]

- Torenz, R. The politics of affirmative consent: Considerations from a gender and sexuality studies perspective. Ger. Law. J. 2021, 22, 718–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beres, M.A. Sexual miscommunication? Untangling assumptions about sexual communication between casual sex partners. Cult. Health Sex. 2010, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, M. Talking Difference: On Gender and Language; SAGE: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey, N.K. Is consent enough? What the research on normative heterosexuality and sexual violence tells us. Sexualities 2024, 27, 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jozkowski, K.N.; Henry, D.S.; Sturm, A.A. College students’ perceptions of the importance of sexual assault prevention education: Suggestions for targeting recruitment for peer-based education. Health Educ. J. 2015, 74, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Byrne, R.; Hansen, S.; Rapley, M. “If a girl doesn’t say ‘no’…”: Young men, rape and claims of ‘insufficient knowledge’. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 18, 168–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, N.E.; Krishnakumar, A.; Leone, J.M. Reexamining issues of conceptualization and willing consent: The hidden role of coercion in experiences of sexual acquiescence. J. Interpers. Violence 2015, 30, 1828–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, S.; Stevanovic, M. Sexual consent as an interactional achievement: Overcoming ambiguities and social vulnerabilities in the initiations of sexual activities. Discourse Stud. 2023, 25, 68–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindesbøl Holm Johansen, K.; Pedersen, B.M.; Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, T. “You can feel that on the person”—Danish young people’s notions and experiences of sexual (non)consenting. NORA Nord. J. Fem. Gend. Res. 2020, 28, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmody, M. Sex and Ethics: Young People and Ethical Sex; Palgrave MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger, C.; Frith, H. Just say no? The use of conversation analysis in developing a feminist perspective on sexual refusal. Discourse Soc. 1999, 10, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coy, M.; Kelly, L.; Elvines, F.; Garner, M.; Kanyeredzi, A. “Sex Without Consent, I Suppose That is Rape”: How Young People in England Understand Sexual Consent; Office of the Children’s Commissioner: London, UK, 2013. Available online: https://assets.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/wpuploads/2014/02/Sex_without_consent_I_suppose_that_is_rape.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Powell, A. Amor fati? Gender habitus and young people’s negotiation of (hetero)sexual consent. J. Sociol. 2008, 44, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowling, M. Rape, Communicative Sexuality and Sex Education. In Making Sense of Sexual Consent; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun, H.L.; Levac, D.; O’Brien, K.K.; Straus, S.; Tricco, A.C.; Perrier, L.; Kastner, M.; Moher, D. Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 1291–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.; Begun, S. Understanding sexual consent among adolescents: Protocol for a scoping review. Soc. Sci. Protocols. 2022, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Senate Judiciary Committee. Violence Against Women: The Increase of Rape in America 1990; National Institute of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 1991. Available online: https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/violence-against-women-increase-rape-america-1990 (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Lumivero NVivo 2020. Available online: https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo/ (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; SAGE: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, G.; Lowe, P. ‘Go on, go on, go on’: Sexual consent, child sexual exploitation and cups of tea. Child. Soc. 2020, 34, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, D. Understanding sexual coercion among young adolescents: Communicative clarity, pressure, and acceptance. Arch. Sex. Behav. 1997, 26, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, D.; Peart, R. The rules of the game: Teenagers communicating about sex. J. Adolesc. 1996, 19, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, V.N.; Simpson-Taylor, D.; Hermann, D.J. Gender, age, and rape-supportive rules. Sex. Roles J. Res. 2004, 50, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clüver, F.; Elkonin, D.; Young, C. Experiences of sexual relationships of young black women in an atmosphere of coercion. Sahara J. J. Soc. Asp. HIV/AIDS 2013, 10, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donovan, C. Young people, alcohol and sex: Taking advantage. Youth Policy 1996, 53, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore, S.; DeLamater, J.; Wagstaff, D. Sexual decision making by inner city black adolescent males: A focus group study. J. Sex. Res. 1996, 33, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hird, M.J. An empirical study of adolescent dating aggression in the UK. J. Adolesc. 2000, 23, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, C.; Impett, E.A.; Schooler, D. Dis/embodied voices: What late-adolescent girls can teach us about objectification and sexuality. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy J. NSRC 2006, 3, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, A.E.; Pettigrew, J.; Miller-Day, M.; Hecht, M.L.; Hutchison, J.; Campoe, K. Resisting pressure from peers to engage in sexual behavior: What communication strategies do early adolescent Latino girls use? J. Early Adolesc. 2015, 35, 562–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, M.A.; Ghani, N.; McKenzie, F.; Rosenberger, J.G.; Bell, D.L. Adolescent boys’ experiences of first sex. Cult. Health Sex. 2012, 14, 781–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvivuo, P.; Tossavainen, K.; Kontula, O. “Can there be such a delightful feeling as this?” Variations of sexual scripts in finnish girls’ narratives. J. Adolesc. Res. 2010, 25, 669–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittington, E. Co-producing and navigating consent in participatory research with young people. J. Child. Serv. 2019, 14, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Byrne, R.; Rapley, M.; Hansen, S. “You couldn’t say ‘no’, could you?”: Young men’s understandings of sexual refusal. Fem. Psychol. 2006, 16, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, J. Contesting consent in sex education. Sex. Educ. 2018, 18, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.L. Yes means yes and no means no, but both these mantras need to go: Communication myths in consent education and anti-rape activism. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2018, 46, 155–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay-Cheng, L.Y. The agency line: A neoliberal metric for appraising young women’s sexuality. Sex. Roles: A J. Res. 2015, 73, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay-Cheng, L.Y.; Eliseo-Arras, R.K. The making of unwanted sex: Gendered and neoliberal norms in college women’s unwanted sexual experiences. J. Sex. Res. 2008, 45, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotell, L. Rethinking affirmative consent in Canadian sexual assault law: Neoliberal sexual subjects and risky women. Akron Law. Rev. 2008, 41, 865–898. [Google Scholar]

- Gavey, R. Affirmative consent to sex: Is it enough? NZWLJ 2019, 3, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Graybill, R. Critiquing the discourse of consent. J. Fem. Stud. Relig. 2017, 33, 175–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulos, C.; Cingel, D.P. Sexual consent on television: Differing portrayal effects on adolescent viewers. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2023, 52, 2589–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggermont, S. Television viewing and adolescents’ judgment of sexual request scripts: A latent growth curve analysis in early and middle adolescence. Sex. Roles 2006, 55, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, L.M. Media and sexualization: State of empirical research, 1995–2015. J. Sex. Res. 2016, 53, 560–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jozkowski, K.N.; Marcantonio, T.L.; Rhoads, K.E.; Canan, S.; Hunt, M.E.; Willis, M. A content analysis of sexual consent and refusal communication in mainstream films. J. Sex. Res. 2019, 56, 754–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcantonio, T.L.; Willis, M.; Rhoads, K.E.; Hunt, M.E.; Canan, S.; Jozkowski, K.N. Assessing models of concurrent substance use and sexual consent cues in mainstream films. J. Am. Coll. Health 2022, 70, 645–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, M.; Canan, S.N.; Jozkowski, K.N.; Bridges, A.J. Sexual consent communication in best-selling pornography films: A content analysis. J. Sex. Res. 2020, 57, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, M.; Jozkowski, K.N.; Canan, S.N.; Rhoads, K.E.; Hunt, M.E. Models of sexual consent communication by film rating: A content analysis. Sex. Cult. 2020, 24, 1971–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, V.A.; Trumbo, S. The relative importance of selected communication skills for positive peer relations: American adolescents’ opinions. Commun. Disord. Q. 2020, 41, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cense, M.; Bay-Cheng, L.; van Dijk, L. ‘Do I score points if I say “no”?’: Negotiating sexual boundaries in a changing normative landscape. J. Gend. Based Violence 2018, 2, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, N.K.; Barata, P.C. “She didn’t want to…and I’d obviously insist”: Canadian university men’s normalization of their sexual violence against intimate partners. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2019, 28, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jozkowski, K.N.; Marcantonio, T.L.; Hunt, M.E. College students’ sexual consent communication and perceptions of sexual double standards: A qualitative investigation. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2017, 49, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaPlante, M.N.; McCormick, N.; Brannigan, G.G. Living the sexual script: College students’ views of influence in sexual encounters. J. Sex. Res. 1980, 16, 338–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denes, A. Biology as consent: Problematizing the scientific approach to seducing women’s bodies. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2011, 34, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, S.; Kosterina, E.V.; Roberts, T.; Brodt, M.; Maroney, M.; Dangler, L. Voices of the mind: Hegemonic masculinity and others in mind during young men’s sexual encounters. Men. Masculinities 2018, 21, 254–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexual Assault Voices of Edmonton Don’t Be That Guy Part 1, Sexual Assault Voices of Edmonton. Available online: https://savedmonton.com/dont-be-that-guy1/ (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Beres, M.A.; Herold, E.; Maitland, S.B. Sexual consent behaviors in same-sex relationships. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2004, 33, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillstrom, L.C. The #metoo Movement; ABC-CLIO: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).