1. Introduction

All individuals, including children and youth with disabilities, have a right to sexuality education that supports healthy development and informed decision-making [

1,

2]. Yet sexuality lessons remain contentious in many regions, leaving curricula outdated and teachers under-prepared [

3,

4]. Schools nevertheless offer a unique setting for integrated learning about human development, relationships, and health [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Comprehensive programs, such as those promoted by the Sex Information and Education Council of Canada, emphasize sequential instruction that supports healthy sexual development and informed decision-making [

3,

7]. Empirical studies show that participation in comprehensive sexuality education is associated with delayed initiation of sexual activity, increased contraceptive use, reduced rates of unintended pregnancy and STIs, and improved communication with partners [

1,

4,

5,

6]. Still, sexuality education in schools remains contentious in many geopolitical regions, including Ontario [

8,

9,

10], where despite updates to the current curriculum documents [

7,

11], schools are still not teaching sexual health content at a comprehensive level to students [

12,

13]. Notably, students with disabilities are rarely visible in Ontario’s Grades 1–12 Health and Physical Education curriculum, limiting their access to relevant and affirming content [

8,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

This study examines young adults with intellectual, developmental, learning, and physical disabilities who completed Ontario secondary school. We ask three questions: (1) What are their levels of sexual knowledge and awareness? (2) What topics do they want a sexuality curriculum to cover? (3) What barriers did they encounter when seeking instruction?

1.1. Background and Literature Review of Comprehensive Sexuality Education

Comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) teaches the cognitive, emotional, physical, and social dimensions of sexuality with the aim of equipping young people to build respectful relationships, make informed health decisions, and claim their rights throughout life [

1]. CSE replaces narrow risk avoidance and purely biological lessons with a holistic discussion of gender, orientation, consent, and positive sexual identity [

7,

9]. Well-delivered programs delay first intercourse, reduce sexual risk-taking, lower rates of pregnancy and sexual disease transmission, and increase condom and contraceptive use as well as knowledge of safer sex practices [

1,

9]. Evidence also links CSE to reductions in intimate partner violence and to safer, more equitable environments for LGBTQ+ students [

4,

10,

11]. These outcomes show that fostering well-being is as important as preventing negative health consequences.

The right to comprehensive sexuality education is affirmed by international bodies, including UNESCO, the World Health Organization, and the United Nations Population Fund [

1,

6,

12]. Governments, therefore, have a duty to provide accurate and unbiased instruction that fulfills this human right. Current classroom practice in Canada falls short of both these standards and the Canadian Guidelines for Sexual Health Education [

3,

7,

9]. National monitoring is limited, provincial curricula vary widely, and most programs were written between 2000 and 2012, leaving many lessons outdated and inconsistent.

1.2. Ontario Sexuality Education Curriculum

Ontario has progressed further than most provinces in updating sexuality content through its Health and Physical Education curriculum, yet significant gaps persist [

9]. The province adopted a new curriculum in 2015 to replace the 1998 framework, but a 2018 repeal by the incoming conservative government required teachers to revert to the older document for one year [

8,

10]. A 2019 revision reinstated most 2015 outcomes but moved teaching on gender identity and expression to grade eight and obligated boards to offer opt-out policies and home-study modules for parents [

7,

9,

11]. Government messaging positioned parents as primary experts even though students report that families seldom provide complete or trusted sexual health information [

9]. Researchers contend that such opt-outs elevate parental preference over the rights of children to comprehensive education and risk limiting student autonomy [

8,

10].

Although Ontario’s updated curriculum includes more topics than previous versions, many key lessons are presented as optional, allowing teachers to omit them according to personal comfort [

8,

10]. Content on gender-based violence, harassment, homophobia, transphobia, and sexual assault is non-mandatory, inaccurately framed, or only briefly mentioned, failing to meet comprehensive education standards [

8]. These omissions are especially serious for students with disabilities who are at greater risk of abuse and may have additional barriers in identifying unsafe situations. Hence, addressing these gaps is essential.

Sexual health lessons in Ontario are nested within the provincial Health and Physical Education curriculum and are usually delivered by physical education teachers and/or public health employees [

12,

13]. Because secondary students take only one compulsory physical education credit, sexual health receives limited instructional time. A survey of sexual health educators in Eastern Ontario schools found that while 85 per cent offered some form of sex education, most lessons promoted abstinence as the primary strategy despite evidence that programs focusing solely on abstinence are ineffective [

13]. Despite provincial guidelines, implementation remains inconsistent across schools, with curriculum flexibility, teacher discretion, and resource gaps contributing to uneven delivery [

8,

12,

13]. Fewer than one-quarter of schools addressed abortion, masturbation, pornography, adoption, or adolescent parenting, and overall alignment with federal sexual health guidelines was poor [

12,

13].

A major gap in Ontario sexual health education is the near absence of content designed for students in special education programming and/or with disabilities [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Because lessons are delivered through Health and Physical Education classes that emphasize gross motor activity, able-bodied and neurotypical norms are reinforced, and learners with physical, neurodevelopmental, psychological, and/or intellectual disabilities are often excluded—particularly in special education streams or segregated classrooms [

18,

19]. The 2019 curriculum notes that accommodations may be needed for special education programs, yet it offers almost no guidance on disability-specific sexuality instruction [

14,

18]. Dedicated, evidence-based lessons for children and youth with disabilities must remain uncommon.

1.3. Disabilities Defined

This review considers three disability groups that are often left out of sexuality education discussions: developmental (including intellectual), learning, and physical disabilities [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Brief definitions, diagnostic criteria, and prevalence estimates for each category clarify their distinct support needs. Recognizing these differences is essential for designing inclusive programs that respect the rights and lived experiences of all learners.

1.3.1. Intellectual Disability

Intellectual disability is a neurodevelopmental condition marked by substantial limitations in intellectual and adaptive functioning that begin in childhood [

20]. DSM-5 diagnosis requires evidence of (i) impaired reasoning, problem solving, planning, abstract thinking, judgment, academic learning, and learning from experience; (ii) restricted everyday adaptive behavior needed for independent living and social responsibility; and (iii) childhood onset [

21]. Ontario legislation groups intellectual disability under “developmental disability” in the Services and Supports to Promote the Social Inclusion of Persons with Developmental Disabilities Act [

22]. Worldwide prevalence is estimated at 1 to 3 per cent, or roughly two hundred million people [

23,

24]. In Ontario, the rate is about 0.7 per cent, representing nearly eighty thousand residents aged 5 and older [

2]. Intellectual disability is often categorized as a developmental disability in Canada, with exact prevalence numbers varying between surveys [

24,

25].

1.3.2. Learning Disability

Learning disabilities comprise a group of disorders that affect the acquisition, organization, retention, or use of verbal and non-verbal information while intellectual and reasoning abilities remain average or above average [

26,

27,

28]. Difficulties arise in one or more processes such as perception-, memory-, or language-based learning [

26]. Canadian prevalence estimates are about 3.2 per cent among children aged 5 to 14 years old and 2.3 per cent among young adults over 15 years old [

26,

27,

28]. Learning disabilities often co-occur with attentional, behavioral, and emotional conditions, underscoring the need for tailored educational supports.

1.3.3. Physical Disability

Physical disability includes limitations in mobility, flexibility, or dexterity, with severity determined by the degree of movement loss. Statistics Canada reports that 18.3 per cent of Canadians over age 15 live with a physical disability; 7.6 per cent experience flexibility limitations, 7.2 per cent mobility limitations, and 3.5 per cent dexterity limitations [

25,

29]. More than two-thirds of these individuals report at least one additional disability, such as mental health, developmental, learning, or pain-related conditions [

25].

1.4. The Social Model of Disability

Developing sexuality curricula that include disability is vital for creating safe learning environments and for equipping students with knowledge that promotes well-being [

2,

6]. In Ontario, many students live with disabilities yet receive little targeted instruction. One barrier is reliance on the medical model, which frames disability as an individual defect in need of cure and thus reinforces able-bodied norms [

30,

31]. This perspective can undermine advocacy by portraying disabled learners as inherently less capable of full social participation. Critics describe the model as disablist because it positions professionals, rather than disabled people themselves, as arbiters of what counts as normal [

32]. Adopting social and rights-based models [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37] would better support inclusive sexuality education.

Because of these limitations, the present study adopts a disability studies perspective that centers the social model of disability [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. This model contests medical assumptions that locate disability within the individual and instead views disadvantage as a product of social and environmental barriers [

37]. Its roots lie in the Fundamental Principles of Disability, which separated impairment (a bodily condition) from disability, described as oppression imposed through exclusion and isolation [

33]. Oliver later formalized this distinction by arguing that people are disabled not by their impairments but by the barriers society constructs around them [

37]. This framework guides our research questions and interpretation of findings.

The social model proposes that society should adapt to include disabled individuals rather than asking them to adapt to existing norms [

34]. When students with disabilities are segregated, they miss vital social learning, an exclusion that violates their right to sexuality education under the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [

1] and increases vulnerability to abuse and inappropriate behavior [

38,

39,

40]. Disability thus arises from external barriers, not inherent impairments, and meaningful change requires schools to remove those barriers and create inclusive environments [

41].

1.5. CSE and Children and Youth with Disabilities: The Current Context

Society often portrays people with disabilities as naïve or asexual and, therefore, restricts their access to sexual health information in an attempt to protect their innocence [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]. Empirical work, however, confirms that they experience the same pubertal changes, desires, and sexual needs as their non-disabled peers [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]. When instruction is inadequate, contraception use declines, and negative outcomes such as sexually transmitted infections, intimate partner violence, and unintended pregnancy increase [

48,

49,

50,

51]. Many youth with disabilities also describe challenges in initiating and sustaining friendships and romantic relationships [

52,

53,

54,

55,

56].

Comprehensive sexuality education helps adolescents with disabilities learn to use contraception, understand their feelings, communicate with partners, and form healthy relationships [

55]. Clear, concrete instruction improves decision-making and allows learners to apply knowledge in everyday contexts, whereas vague or highly technical lessons often fail to transfer for students with intellectual, developmental, or learning disabilities [

54]. Effective programs also support earlier recognition and prevention of sexual abuse and empower students to express their sexuality in safe, appropriate ways [

52,

53,

54,

55,

56].

1.6. Barriers to Effective CSE for Children and Youth with Disabilities

People with disabilities have often been denied sexuality education and the right to make informed sexual health decisions [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. This exclusion is fueled by stereotypes that they are asexual [

15] or incapable of providing valid consent [

14]. Caregivers are pivotal educators, yet many find sexuality topics difficult to discuss with their disabled children [

57,

58,

59,

60]. When information is withheld, vulnerability rises, inappropriate behavior may increase, and opportunities to build healthy relationships diminish [

59]. Inclusive evidence-based education can, therefore, enhance safety, support positive relationships, and improve quality of life for disabled [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

Caregivers frequently report that they lack the knowledge and confidence to handle sexuality topics with their children [

57,

58,

59,

60]. A meta-analysis found that uncertainty about appropriate content, confusion over who should initiate discussion, and the tension between protection and facilitation are the main obstacles [

51]. Targeted education for caregivers on sexual development can increase their competence and reduce barriers for youth with disabilities [

57].

Limited privacy and freedom present another barrier. Family rules that restrict independence often lead to disapproval of intimate relationships, limited private space, and constraints on sexual expression, all of which reduce opportunities for positive sexual experiences [

58,

59,

60]. Creating supportive home and school environments that respect autonomy is, therefore, essential for comprehensive sexuality education [

61,

62].

Consent law can also restrict sexual expression. The general age of consent in Canada is 16 years old, yet the Criminal Code states that persons who lack sufficient mental capacity cannot legally consent regardless of age [

63]. This rule may limit the sexual rights of some disabled individuals and give substitute decision makers disproportionate control [

64]. Frameworks that assess capacity while safeguarding against harm and upholding the right to sexual expression are, therefore, needed.

1.7. Key Stakeholders in Developing Effective CSE for Children and Youth with Disabilities

Many youth with disabilities receive no formal sexuality instruction, and parents often assume schools will supply it [

65]. Most caregivers lack professional training and are unsure what to cover [

57,

58,

59,

60]. Parent-oriented programs improve knowledge, lower anxiety, and curb misinformation, enabling families to champion their children’s right to safe sexual expression [

62]. Teachers also report limited preparation for disability inclusive lessons; targeted professional development that offers practical tools and raises awareness is essential for closing this gap [

18].

Peer interaction is a key but often overlooked source of sexual learning. Much knowledge about relationships and social norms is acquired informally through conversations in hallways, at lunch, or during activities outside class [

36]. These contexts are frequently unavailable to students in segregated special education, who have fewer chances to mix with non-disabled peers and practice social cues [

36,

38]. Limited interaction can marginalize youth with disabilities and restrict exploration of their sexuality. Including peers in planned lessons can promote learning about personal space, conversation skills, and consent while making materials more engaging and accessible [

66].

Lack of Research on Students with Disabilities’ Perspectives

Although scholars agree that sexuality education is essential for all children, and particularly for those with disabilities [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], few studies capture the voices of disabled students themselves; most examine parent or caregiver views and curricular controversies [

10,

14,

16,

18,

56,

57]. Tensions often arise when the rights of young people to receive inclusive education conflict with parental wishes, a dilemma that becomes acute when adolescents and caregivers hold opposing beliefs, for example, about LGBTQ+ identities [

16]. Disabled LGBTQ+ youth report fewer peer connections, dismissal of gender dysphoria, and barriers to health care, factors that heighten bullying and victimization risk [

67]. Expanding research that centers student perspectives is, therefore, critical for guiding rights-based, inclusive practice.

Ideas about “protecting childhood innocence” cast childhood as an unquestioned state of dependence governed by developmental norms [

68,

69]. This frame often blocks classroom discussion of gender diversity and identity and leaves sexual-minority students vulnerable when parents control what they may learn [

14,

15,

16,

17,

70]. Ethical concerns, therefore, arise when parental vetoes decide whether children can participate in comprehensive sexuality education [

8,

10,

14,

15,

16].

1.8. The Current Study

Participants completed the Sex Education subscale of the Sexual Knowledge, Experience, Feelings and Needs Scale to rate desired curriculum content [

71]. Knowledge and awareness were assessed with the General Sexual Knowledge Questionnaire [

72] and the Sexual Awareness Questionnaire [

73]. Scores were compared with data from non-disabled peers reported by Hannah and Stagg [

74]. Open-ended items then allowed respondents to explain their answers and describe real-life experiences, linking questionnaire scores to personal beliefs and behaviors.

2. Materials and Methods

The current study aimed to examine the sexual knowledge, educational needs, and lived experiences of young adults with developmental, learning, or physical disabilities who completed secondary school in Ontario. Drawing on a mixed-methods design, we addressed three core research questions: (1) What are young adults’ levels of sexual knowledge and awareness? (2) What topics do young adults want in a sexuality curriculum to cover? (3) What barriers do young adults encounter when seeking instruction?

2.1. Research Ethics

The described study was conducted under the Research Ethics certificate number 21-12-030 issued by the University of Guelph Research Ethics Board on 23 March 2022. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Participants

Fifty-four young adults aged 18–35 completed the survey. Eligibility criteria included self-identifying as having a developmental, learning, or physical disability and having completed secondary school in Ontario. Participants were recruited through disability-focused social media groups, community organizations, and a university psychology participant pool. Recruitment relied on disability themed social media groups and organizations (22 participants) and the university psychology participant pool (32 participants). Participation was voluntary, and recruitment materials emphasized that individuals could opt in anonymously and withdraw at any time without penalty.

2.3. Research Design

We employed a cross-sectional mixed-methods design, combining a quantitative descriptive approach and qualitative descriptive inquiry to capture both general trends and lived experiences. This design followed Tashakkori and Creswell’s framework for mixed-methods research [

75], with equal weighting given to quantitative and qualitative strands. The quantitative component involved descriptive and inferential analyses of three standardized instruments, including means, standard deviations, and independent samples

t-tests. These analyses addressed research questions 1 and 2, which explored levels of sexual knowledge, awareness, and desired curriculum content. The qualitative component used an inductive thematic analysis, guided by Braun and Clarke’s six-phase approach, to examine 12 open-ended responses. This allowed us to explore research question 3 on disabling barriers to sexuality education. Together, these methods provided an exploratory, contextual understanding of participants’ experiences and enabled integration of statistical trends with personal narratives.

2.4. Materials

Sex Education subscale of the SexKen-ID contains 16 items that ask about prior exposure to lessons, attitudes toward those lessons, and perceived need for further instruction. Responses are scored on a five-point scale; reliability and validity are well established [

71,

72].

Sexual Awareness Questionnaire has 36 items rated from zero to four that measure sexual consciousness, sexual monitoring, sexual assertiveness, and sex-appeal consciousness. The scale shows good internal consistency and convergent validity [

73].

The General Sexual Knowledge Questionnaire is a 47-item revision of the Bender Sexual Knowledge Questionnaire [

76] that measures knowledge of anatomy, intercourse, pregnancy, contraception, infections, and sexuality [

72]. Although developed for people with intellectual disability, it is suitable for the present sample; non-disabled participants are expected to score higher [

77]. Internal consistency and split-half reliability are good, but validity data are limited [

72]. To reduce burden, we selected 17 non-redundant items plus two body-labeling diagrams, a format that still captures key constructs while keeping completion time reasonable.

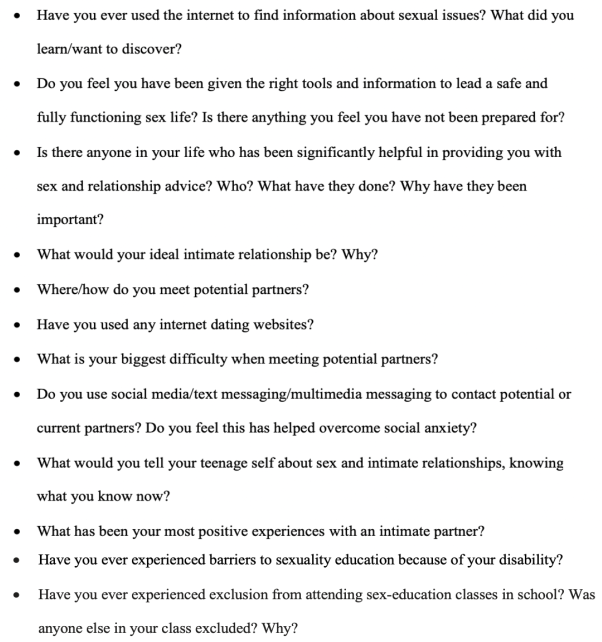

The survey also included 12 open-ended items. Ten were adapted from a previous study of autistic young adults [

74], and two new questions asked participants to describe disabling barriers they encountered in sexuality education. The full list of open-ended survey questions is provided in

Appendix A.

2.5. Procedure

This study employed a cross-sectional mixed-methods survey design that combined quantitative and qualitative approaches to examine the sexuality education experiences of young adults with disabilities.

Data were collected in October and November 2022. Recruitment drew on disability-focused social media, community organizations, and a university participant pool. After providing electronic consent, respondents completed a Qualtrics survey that combined closed-ended scales with open-ended items; assistance from caregivers or the researcher was available, and no time limit was set. Consent materials were presented in plain language to support accessibility. Participants were informed that assistance from a caregiver or the research team was available upon request to ensure comprehension and ease of participation. Qualitative answers were examined inductively using Braun and’s six-phase thematic analysis [

78].

Qualitative responses from the 12 open-ended questions were first sorted by research focus—sexual awareness, barriers to education, and information sources—to align each answer with the corresponding research question. This organization provided a clear framework for subsequent analysis. Following Braun and Clarke’s six-step procedure, coding moved inductively from line-by-line labels to broader categories, with constant comparison across all questions to capture patterns that spanned topics [

78]. Codes were then clustered into candidate themes, which the research team reviewed for internal coherence and distinctiveness. Final themes were named and defined to reflect the core ideas in the data and to present a coherent, evidence-based interpretation of participants’ experiences. This systematic approach ensured a comprehensive understanding of how young adults with disabilities perceive their knowledge, needs, and barriers in sexuality education.

Data integration occurred at the interpretation stage, where quantitative results were used to identify patterns in knowledge and awareness, and qualitative themes were examined to contextualize and explain those patterns. For example, lower sexual assertiveness scores on the Sexual Awareness Questionnaire were interpreted alongside qualitative accounts of social anxiety and difficulty navigating relationships. This complementary approach allowed us to connect statistical findings with lived experience, enhancing the validity and relevance of the study’s conclusions.

3. Results

To allow comparison with non-disabled peers, data from the present sample (Group 1, young adults who self-identified as disabled) were analyzed alongside published scores from a matched cohort without disabilities (Group 2) reported by Hannah and Stagg [

74]. These group labels are used throughout the

Section 3. Participants were predominantly aged 18–25 (89%). The sample was mostly White European (69%) and female (63%), with 19% identifying as male and 18% as non-binary or gender diverse. Education levels varied: 52% had some post-secondary study, 26% had completed high school, 11% held a college diploma, 7% an undergraduate degree, and 4% a graduate degree. Reported disabilities included learning (46%), physical (26%), intellectual or developmental (24%), and combined physical plus developmental (4%). Participants also reported diverse sexual orientations: 54% identified as heterosexual, 15% as bisexual, 9% as queer, 7% as questioning, 6% as lesbian, 4% as pansexual, 4% as asexual, and 2% as gay.

Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the 54 participants, including age, gender, education, disability type, and sexual orientation.

3.1. Sexual Knowledge, Experience, Feelings and Needs Scale

An independent samples

t test compared Sex Education Feelings scores for Group 1 (M = 17.5, SD = 2.0, n = 54) and Group 2 (M = 16.7, SD = 2.3, n = 20, drawn from Hannah and Stagg [

74]). The difference was not significant,

t(72) = 1.52,

p = 0.064.

For the Needs subscale, Group 1 scored higher (M = 8.7, SD = 2.3) than Group 2 (M = 7.2, SD = 1.8), with a significant difference, t(72) = 2.80, p = 0.006, showing that participants with disabilities expressed a greater need for sexuality education.

Experiences scores were available only for Group 1 (M = 15.2, SD = 3.8) because the comparison study did not use that subscale, so no between-group test was possible.

3.1.1. Sexual Awareness Questionnaire

Independent

t-tests compared subscale means for the disability sample (Group 1) and the non-disabled comparison group (Group 2). Group 1 recorded lower sexual consciousness (M = 14.4, SD = 5.2) than Group 2 (M = 18.2, SD = 3.6), t(72) = 2.96,

p = 0.004, and lower sexual assertiveness (M = 13.2, SD = 5.3) than Group 2 (M = 16.3, SD = 5.0), t(72) = 2.24,

p = 0.028. No group differences emerged for sexual monitoring (M = 19.2 vs. 19.5, t = 0.23,

p = 0.82) or sex-appeal consciousness (M = 12.2 vs. 16.3, t = 1.52,

p = 0.14). These findings indicate lower self-awareness and assertiveness but comparable social monitoring and body confidence among participants with disabilities [

73].

3.1.2. General Sexual Knowledge Questionnaire

Group 1 scored an average of 25.1 (SD 6.5) on the shortened GSKQ, equivalent to 48 per cent correct, with individual scores ranging from 17 to 75 per cent. This performance mirrors the 41 per cent average reported for young adults with intellectual disability and remains far below the 75 per cent average for non-disabled peers [

72]. These quantitative findings were contextualized by participants’ open-ended responses, which revealed why knowledge gaps may exist—highlighting exclusionary curriculum content, inaccessible delivery, and the need for inclusive approaches to sexuality education.

3.1.3. Qualitative Analysis

Inductive analysis produced six themes: inadequate school instruction, reliance on self-teaching, limited experience, confusion about relationship norms, social anxiety, and inaccessible materials (

Figure 1).

3.1.4. Inadequate Sexuality Education

Most participants described classroom lessons as narrow, biology-centered, and abstinence-oriented, prompting them to search elsewhere for meaningful guidance. P37 “learned mostly from TV and the internet,” while As P3 explained, “We had very basic sex education in school—just biology, like the reproductive system. I had to Google everything else myself. No one taught us about relationships or consent.” When lessons ignored topics such as pleasure and consent, learners blended information from parents, peers, and media; As P26 reflected, “Honestly, friends and the internet were the most helpful. They gave me real answers that didn’t feel shameful or weird. School just left everything out.”. Several respondents advised their younger selves to bypass limited school content and explore reputable online resources instead. These accounts illustrate how perceived shortcomings in school programs drive students with disabilities to construct their own sexuality education from informal channels.

3.2. Reliance on Self-Education

3.2.1. Inexperience

Many respondents had never dated or engaged in sexual activity. P23 noted, “I have not had many positive experiences with partners,” and P18 shared, “I’ve never been in a romantic relationship. There just weren’t chances or spaces to explore that safely.” Others left relationship items blank or wrote “not applicable,” signaling similar inexperience. This lack of practice fostered anxiety; P35 worried about “saying the right things and being liked,” while P51 sought “an empathetic partner” who would understand their inexperience. These accounts reveal how limited opportunities to date leave some young adults with disabilities feeling vulnerable and self-conscious when approaching relationships.

3.2.2. Navigating Relationships

Participants described difficulty interpreting intentions and expressing their own feelings when dating. As P2 put it, “I can’t tell if someone is flirting or just being friendly. It’s confusing and I worry I’ll get it wrong.” Whereas P3 found it hard to know if two people share compatible desires. Others reported challenges with self-expression (P41), limited social awareness (P10), trouble establishing mutual attraction (P6), and worry about seeming inappropriate (P7). These accounts point to gaps in the knowledge and skills needed to read social cues, communicate desires, and form respectful relationships, underscoring a critical area for sexuality education.

3.2.3. Social Anxiety

Many participants linked difficulties in meeting partners to persistent social anxiety. P23 explained, “I want to talk to people, but my anxiety gets in the way. I freeze up and then overthink everything I said.”. Whereas P22 felt “self-conscious and not wanting to talk to new people.” Worries about others’ judgments were common. P42 noted that ADHD made them fear “saying something wrong… which could ruin a connection,” and P36 also became anxious about how they were perceived. Past negative experiences fueled distrust; P54 feared being harmed again, and P18 and P12 reported concern about being used. These accounts show how anxiety, insecurity, and limited trust create substantial barriers to forming relationships for many young adults with disabilities.

3.2.4. Inaccessibility

Many respondents said school provided no sexuality instruction at all, or only biology-focused lessons, leaving them to learn from parents or the internet. Several linked exclusion directly to their disability, recalling that classmates in special education or autism programs were withdrawn from classes other students attended [

36]. Even when lessons were offered, they rarely addressed disability, LGBTQIA+ issues, or female pleasure. As P37 described, “I had to research myself about disabilities and sex. There was nothing in school. No one talked about what it’s like for someone like me.” Teaching methods were seldom adapted to diverse learning needs, leading some to “retain less” because teachers did not accommodate different styles. Gender-segregated classes further limited understanding of the opposite body and reinforced gaps in knowledge. Together, these experiences show how inaccessible formats and missing disability-specific content restrict students’ right to a comprehensive education.

4. Discussion

This study assessed sexual knowledge, awareness, and educational needs among young adults with developmental, learning, and physical disabilities. Findings revealed limited sexual knowledge, unmet educational needs, lower sexual assertiveness and awareness, and diverse barriers to accessing inclusive sexuality education [

15,

79]. Three validated questionnaires and 12 open-ended items addressed three questions: current knowledge and awareness, barriers to accessing instruction, and desired curriculum content. By integrating both quantitative scores and lived experience narratives, our mixed-methods design revealed not only what participants lacked in terms of sexual health knowledge, but also why those gaps emerged—namely, exclusionary content and inaccessible delivery.

Quantitative results showed lower knowledge, reduced sexual consciousness, and greater unmet educational need among participants with disabilities. Qualitative analysis yielded six themes: inadequate school instruction, reliance on self-teaching, limited experience, difficulty interpreting others, social anxiety, and inaccessible or disability-exclusive content. Together, these findings confirm that school-based programs often fall short for disabled learners and point to the need for comprehensive, disability-affirming sexuality education.

What are the sexual knowledge and awareness levels of individuals with disabilities?

Participants averaged 48 per cent correct on the shortened GSKQ, with scores spanning 17 to 75 per cent. This mirrors the 41 per cent reported for young adults with intellectual disability in Talbot and Langdon [

72] and remains well below the 75 per cent found in non-disabled samples. Variation in scores likely reflects differences in disability type, access to information, and education level.

Sexual Awareness Questionnaire results showed significantly lower sexual consciousness and sexual assertiveness among participants with disabilities than among non-disabled peers [

16]. These findings suggest challenges in recognizing personal sexual feelings, expressing needs, setting boundaries, and advocating for one’s sexual well-being.

Scores for sexual monitoring and sex-appeal consciousness did not differ between groups (

p > 0.05), indicating that participants with disabilities were as aware as peers of how others view their sexuality and of their own attractiveness [

16]. This parity may stem from supplementary learning in post-secondary settings. Even so, lower scores for sexual consciousness and assertiveness show distinct educational needs. Research with autistic young adults found reduced awareness across all SAQ domains, underscoring how disability influences sexual self-perception [

74]. Qualitative themes such as difficulty grasping course content, interpreting others, social anxiety, and limited dating experience help explain weaker GSKQ performance. Participants described classroom lessons as indirect or overly technical, a delivery style known to hinder real-world application of knowledge [

36,

52]. Accessible, targeted instruction is, therefore, essential.

Many participants had little or no dating or sexual experience and described feeling anxious, self-conscious, and unsure how to approach or interpret potential partners. They found it hard to decide whether an interaction should remain friendly or become romantic, struggled to read social cues, and worried about seeming inappropriate. Past negative encounters left some unwilling to trust others. These accounts align with the survey’s lower scores for sexual consciousness and assertiveness and echo earlier research showing that youth with disabilities often find it difficult to start and sustain friendships and romantic relationships [

14,

18,

36,

49,

50,

51]. Effective programs must pair factual content with explicit, accessible coaching in social and relationship skills.

Have individuals with disabilities experienced disabling barriers related to sexuality education?

Participants identified several obstacles that limited their access to meaningful instruction. Many received little or no school-based education because lessons were not offered in special education streams or lacked disability-specific content. Others who did attend classes found the material hard to understand or irrelevant to their lived experience. They called for curricula that address disability concerns, incorporate LGBTQIA+ perspectives, and present balanced information on female as well as male pleasure. Gender segregation during lessons further restricted learning by preventing discussion of bodies and experiences different from one’s own. These findings echo earlier work showing that students in specialized programs are often excluded from comprehensive sexuality education and struggle to grasp content that is not delivered in accessible formats [

14,

18].

Given the clear educational gaps identified, our findings reinforce the importance of introducing sexuality education at an earlier age. Beginning instruction in primary or early secondary school can help ensure that foundational knowledge, values, and skills are built before young people begin exploring intimate relationships. This is especially important for students with disabilities, who may be excluded from informal learning and require accessible, intentional instruction. Future research should also focus on younger adolescents with disabilities, as this group remains critically underrepresented in the literature despite their unique developmental needs and the opportunity for early intervention.

Scores on the SexKen-ID showed that participants valued sexuality education as highly as non-disabled peers, yet indicated a significantly greater unmet need for it. This gap reflects the persistent shortfall in opportunities reported in earlier work on disabled learners [

41]. Qualitative responses confirmed the demand for tailored content that explains disability-specific concerns, includes LGBTQIA+ perspectives, and teaches practical skills for making friends, dating, and reducing loneliness—needs also identified in adolescent studies by Löfgren [

80]. Taken together, these data underline that comprehensive programs must go beyond biological facts to address the diverse realities and relationship goals of students with disabilities.

4.1. Inadequate Sexuality Education and Reliance on Self-Education

School lessons were described as narrow, biology-centered, and abstinence-oriented, omitting pleasure, consent, and relationship skills. To fill these gaps, participants turned to parents, friends, television, and, most often, the internet, even though parents generally lack formal training and online information can be unreliable [

36]. Similar reliance on self-teaching has been reported among young adults with intellectual disability and LGBTQIA+ youth when formal curricula ignore their needs [

18]. These findings underline the need for accessible, comprehensive classroom programs.

4.2. Implications for Research, Education, and Practice

These findings have important implications for the development and implementation of sexuality education programs. Educationally, they support the integration of disability-affirming, inclusive, and accessible content into school-based curricula. Practically, educators and service providers should be trained to deliver content that reflects the lived experiences of students with disabilities, including LGBTQIA+ identities, relationship dynamics, and pleasure-focused instruction. At the policy level, greater attention is needed to ensure that sexuality education is mandated and delivered equitably across special education settings. From a research perspective, this study contributes to the limited literature on young adults with disabilities and highlights the need for continued investigation into effective strategies for delivering sexuality education that meets their diverse needs.

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Several caveats temper these findings. First, explicit self-report measures invite socially desirable answers, especially on sensitive topics, which may dampen accuracy. Second, most respondents had some post-secondary education, so results may not generalize to the wider disability community. Third, group sizes were unequal: the disability sample was larger than the historic comparison group, which could skew test statistics. Fourth, shortening the GSKQ to reduce the burden may have weakened its reliability and construct coverage.

Future studies should recruit a broader cross-section of people with disabilities across ages, education levels, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Researchers also need updated, inclusive instruments that reflect current terminology and the experiences of LGBTQIA+ communities. Future research could also benefit from engaging curriculum developers and educators directly to explore how sexual health instruction is designed and implemented in classroom settings, particularly with respect to inclusive and disability-affirming approaches. Finally, intervention trials comparing delivery formats, for example, peer-led classes, accessible digital modules, and caregiver-supported sessions, would help policymakers and educators adopt the most effective strategies for disability-affirming sexuality education.