Relationships between Coerced Sexting and Differentiation of Self: An Exploration of Protective Factors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

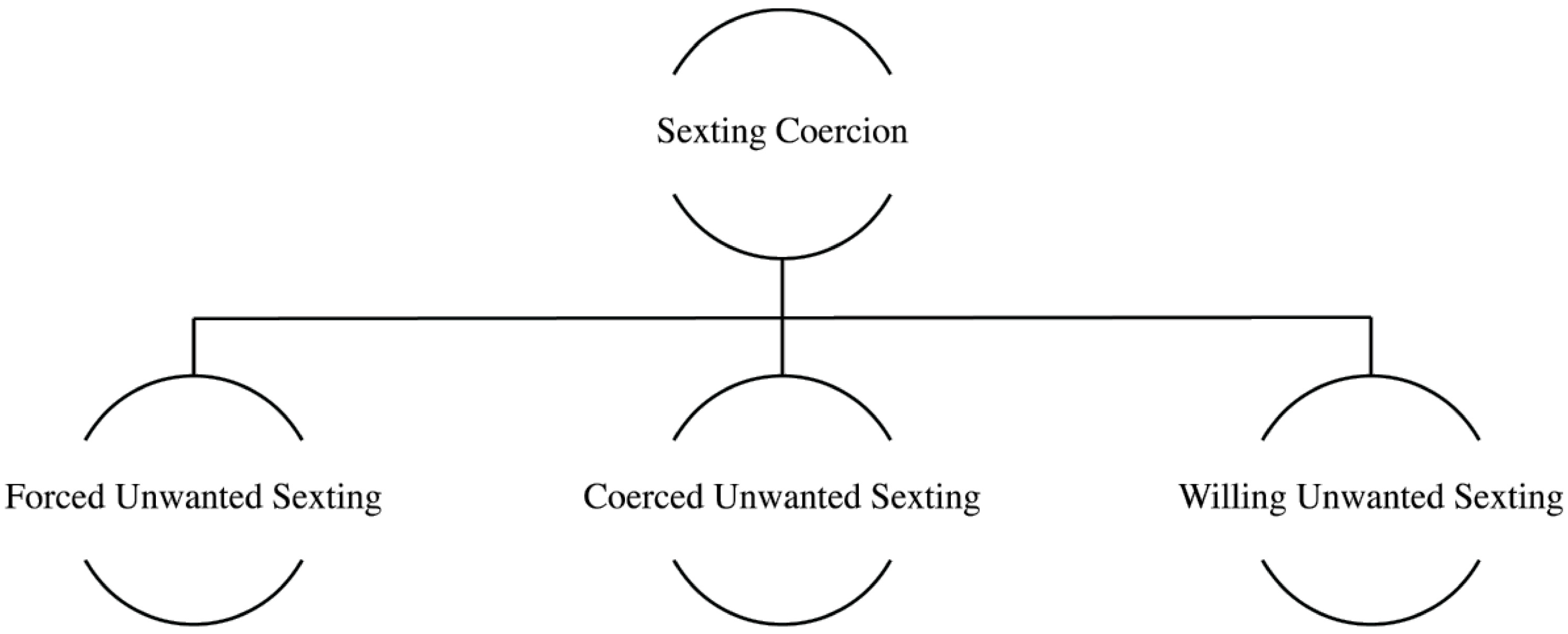

1.1. Concepetualising Sexting Coercion

1.2. Sexting Coercion and Gender

1.3. Sexting Coercion and Self-Regulation

1.4. Study Aims

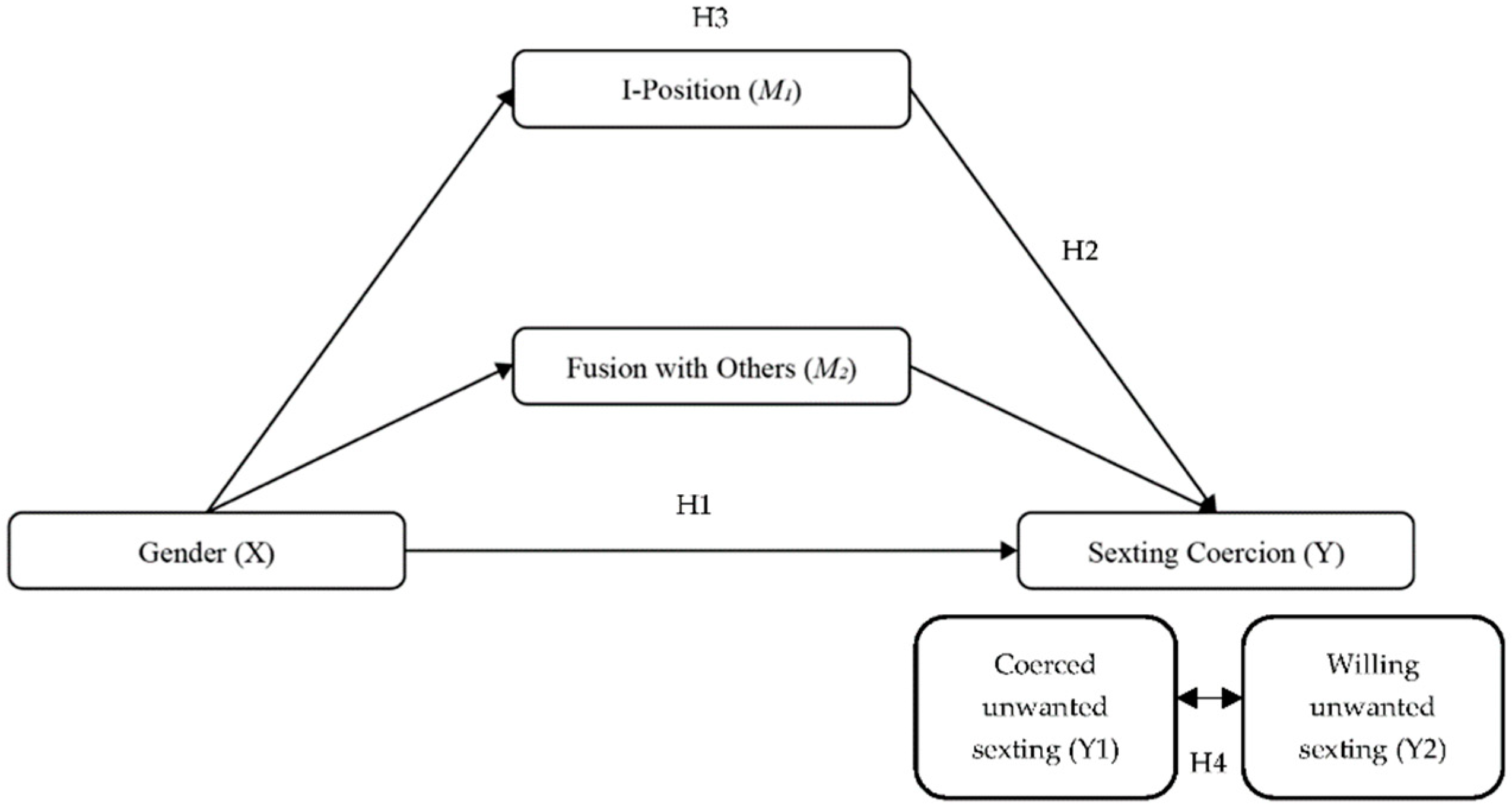

- Women would be more likely to experience coerced unwanted and willing unwanted sexting than men;

- Low DoS would be associated with an increased likelihood of experiencing coerced unwanted and willing unwanted sexting;

- DoS would mediate the relationship between gender and coerced unwanted sexting and willing unwanted sexting; and,

- Coerced unwanted sexting and willing unwanted sexting are associated with each other.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Sexting Coercion and Gender

3.3. Sexting Coercion and Differentiation of Self

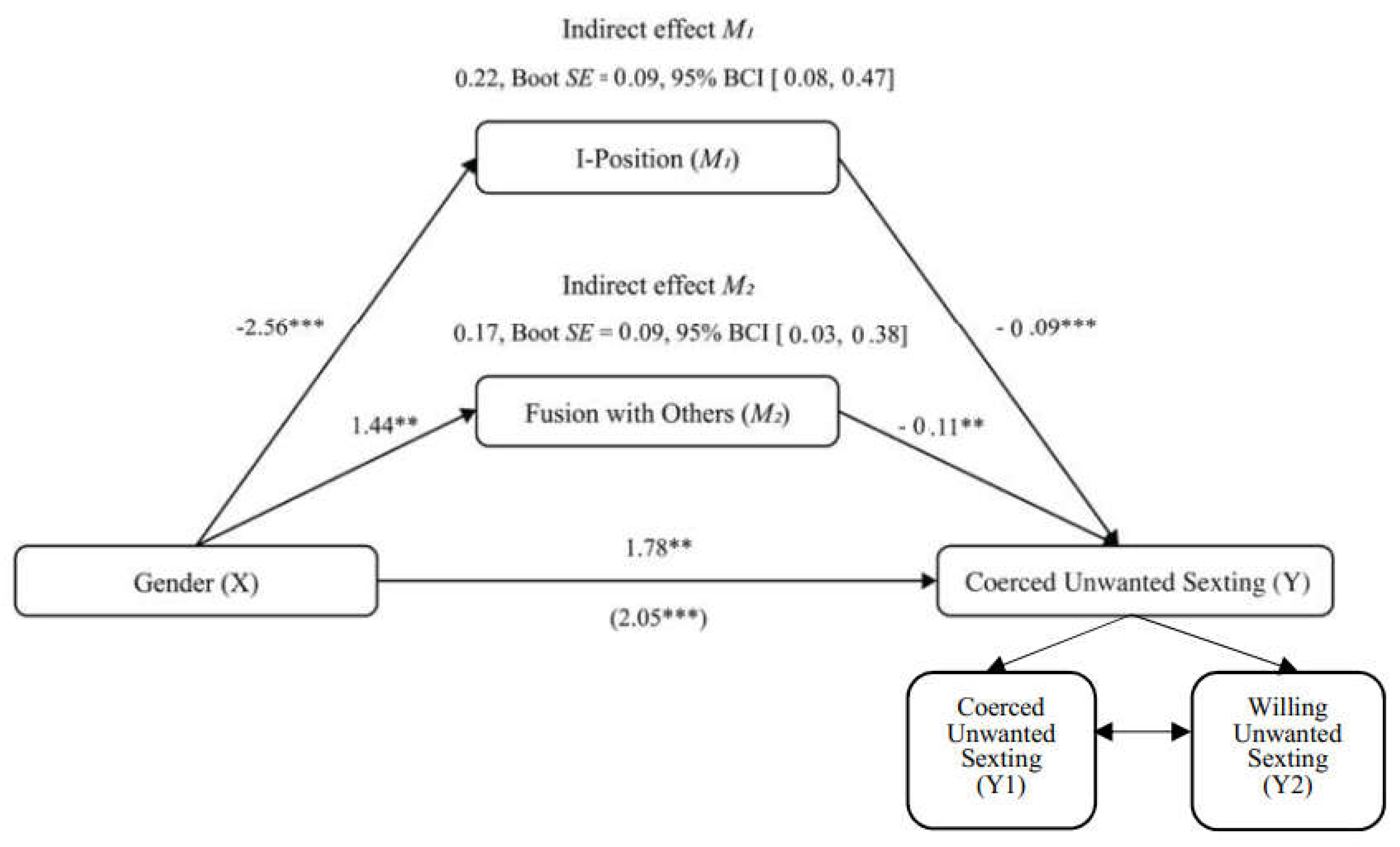

3.4. Gender and Sexting Coercion Mediated by Differentiation of Self

3.5. Willing Unwanted Sexting and Coerced Unwanted Sexting

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Practice

4.2. Limitations and Direction for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Klettke, B.; Hallford, D.J.; Clancy, E.; Mellor, D.J.; Toumbourou, J.W. Sexting and psychological distress: The role of unwanted and coerced sexts. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2019, 22, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barroso, R.; Ramião, E.; Figueiredo, P.; Araújo, A.M. Abusive sexting in adolescence: Prevalence and characteristics of abusers and victims. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strasburger, V.C.; Zimmerman, H.; Temple, J.R.; Madigan, S. Teenagers, sexting, and the law. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20183183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, J.M.; Drouin, M.; Coupe, A. Sexting coercion as a component of intimate partner polyvictimization. J. Interpers. Violence 2019, 34, 2269–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouin, M.; Ross, J.; Tobin, E. Sexting: A new, digital vehicle for intimate partner aggression? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 50, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Crofts, T. Gender, pressure, coercion and pleasure: Untangling motivations for sexting between young people. Br. J. Criminol. 2015, 55, 454–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Van Ouytsel, J.; Temple, J.R. Association between sexting and sexual coercion among female adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2016, 53, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drouin, M.; Tobin, E. Unwanted but consensual sexting among young adults: Relations with attachment and sexual motivations. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.; Quayle, E.; Jonsson, L.; Svedin, C.G. Adolescents and self-taken sexual images: A review of the literature. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dake, J.A.; Price, J.H.; Maziarz, L.; Ward, B. Prevalence and correlates of sexting behavior in adolescents. Am. J. Sex. Educ. 2012, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, D. Sexting: A Terrifying health risk … or the new normal for young adults? J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 52, 257–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, J.J.; Klettke, B.; Hall, K.; Clancy, E.; Hallford, D. Demographic and psychosocial factors associated with child sexual exploitation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2017682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crofts, T.; Lee, M. Sexting, children and child pornography. Syd. Law Rev. 2013, 35, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Baumler, E.; Temple, J.R. Multiple forms of sexting and associations with psychosocial health in early adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, N.; Powell, A. Beyond the ‘Sext’: Technology-facilitated sexual violence and harassment against adult women. Aust. N. Z. J. Criminol. 2015, 48, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, N.; Powell, A. Technology-facilitated sexual violence: A literature review of empirical research. Trauma Violence Abus. 2018, 19, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kernsmith, P.D.; Victor, B.G.; Smith-Darden, J.P. Online, offline, and over the line: Coercive sexting among adolescent dating partners. Youth Soc. 2018, 50, 891–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englander, E. Low Risk Associated With Most Teenage Sexting: A Study of 617 18-Year-Olds; Massachusetts Aggression Reduction Center Research Reports 6; Bridgewater State University: Bridgewater, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- RAV. Sexting; Page; Relationships Australia Victoria (RAV): Melbourne, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, L.A.; Tolman, R.M.; Ward, L.M. Snooping and sexting: Digital media as a context for dating aggression and abuse among college students. Violence Women 2016, 22, 1556–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machimbarrena, J.M.; Calvete, E.; Fernández-González, L.; Álvarez-Bardón, A.; Álvarez-Fernández, L.; González-Cabrera, J. Internet risks: An overview of victimization in cyberbullying, cyber dating abuse, sexting, online grooming and problematic internet use. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2018, 15, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Döring, N. How is the COVID-19 pandemic affecting our sexualities? An overview of the current media narratives and research hypotheses. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2020, 49, 2765–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J.E.; Raghavan, C. The impact of coercive control on use of specific sexual coercion tactics. Violence Women 2021, 27, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, E.; Johnson, I.; Sigler, R. Gender differences in perceptions for women’s participation in unwanted sexual intercourse. J. Crim. Justice 2006, 34, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, N.; Barter, C.; Wood, M.; Aghtaie, N.; Larkins, C.; Lanau, A.; Överlien, C. Pornography, sexual coercion and abuse and sexting in young people’s intimate relationships: A european study. J. Interpers. Violence 2018, 33, 2919–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger, M.A. Unpacking “sexting”: A systematic review of nonconsensual sexting in legal, educational, and psychological literatures. Trauma Violence Abus. 2017, 18, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringrose, J.; Harvey, L.; Gill, R.; Livingstone, S. Teen girls, sexual double standards and ‘sexting’: Gendered value in digital image exchange. Fem. Theory 2013, 14, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brem, M.J.; Stuart, G.L.; Cornelius, T.L.; Shorey, R.C. A Longitudinal examination of alcohol problems and cyber, psychological, and physical dating abuse: The moderating role of emotion dysregulation. J. Interpers. Violence 2019, 36, 886260519876029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trub, L.; Starks, T.J. Insecure attachments: Attachment, emotional regulation, sexting and condomless sex among women in relationships. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 71, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ouytsel, J.; Walrave, M.; Ponnet, K.; Heirman, W. The association between adolescent sexting, psychosocial difficulties, and risk behavior: Integrative review. J. Sch. Nurs. 2015, 31, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berger, A.; Kofman, O.; Livneh, U.; Henik, A. Multidisciplinary Perspectives on attention and the development of self-regulation. Prog. Neurobiol. 2007, 82, 256–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houck, C.D.; Barker, D.; Rizzo, C.; Hancock, E.; Norton, A.; Brown, L.K. Sexting and sexual behavior in at-risk adolescents. Pediatrics 2014, 133, e276–e282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McDaniel, B.T.; Drouin, M. Sexting among married couples: Who is doing it, and are they more satisfied? Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2015, 18, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Reyns, B.W.; Henson, B.; Fisher, B.S. Digital deviance: Low self-control and opportunity as explanations of sexting among college students. Sociol. Spectr. 2014, 34, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisskirch, R.S.; Delevi, R. “Sexting” and adult romantic attachment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 1697–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassó, A.M.; Klettke, B.; Agustina, J.R.; Montiel, I. Sexting, mental health, and victimization among adolescents: A literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hainlen, R.L.; Jankowski, P.J.; Paine, D.R.; Sandage, S.J. Adult Attachment and well-being: Dimensions of differentiation of self as mediators. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 2016, 38, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandage, S.J.; Jankowski, P.J.; Bissonette, C.D.; Paine, D.R. Vulnerable narcissism, forgiveness, humility, and depression: Mediator effects for differentiation of self. Psychoanal. Psychol. 2017, 34, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowron, E.A.; Platt, L.F. Differentiation of self and child abuse potential in young adulthood. Fam. J. 2005, 13, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorberg, F.A.; Lyvers, M. Attachment, fear of intimacy and differentiation of self among clients in substance disorder treatment facilities. Addict. Behav. 2006, 31, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, J.R.; Murdock, N.L.; Marszalek, J.M.; Barber, C.E. Differentiation of self inventory—Short form: Development and preliminary validation. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 2015, 2, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burri, A.; Schweitzer, R.; O’Brien, J. Correlates of female sexual functioning: Adult attachment and differentiation of self. J. Sex. Med. 2014, 11, 2188–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murdock, N.L.; Gore, P.A., Jr. Stress, coping, and differentiation of self: A test of bowen theory. Contemp. Fam. Ther. Int. J. 2004, 26, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowron, E.; Stanley, K.; Shapiro, M. A Longitudinal perspective on differentiation of self, interpersonal and psychological well-being in young adulthood. Contemp. Fam. Ther. Int. J. 2009, 31, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, F.; Koolaee, A.K.; Zadeh, M.R. The comparison of self-differentiation and self-concept in divorced and non-divorced women who experience domestic violence. Int. J. High Risk Behav. Addict. 2013, 2, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schnarch, D.; Regas, S. The crucible differentiation scale: Assessing differentiation in human relationships. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2012, 38, 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.; Xu, Z.-Y.; Zaroff, C.; Chi, P.; Du, H.; Ungvari, G.S.; Chiu, H.F.K.; Yang, Y.-P.; Xiang, Y.-T. Associations of differentiation of self and adult attachment in individuals with anxiety-related disorders. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2018, 54, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousefi, N.; Kiani, M.A. The study of two psychotherapy approaches (rogers self theory and ellis rational theory) in improvement of bowen self-differentiation and intimacy. Iran. J. Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 2014, 8, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shaghaghi, A.; Bhopal, R.S.; Aziz, S. Approaches to recruiting ‘Hard-to-Reach’ populations into research: A review of the literature. Health Promot. Perspect. 2011, 1, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skowron, E.A.; Friedlander, M.L. The differentiation of self inventory: Development and initial validation. J. Couns. Psychol. 1998, 45, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowron, E.A. Assessing Interpersonal fusion: Reliability and validity of a new DSI fusion with others subscale. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2003, 29, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 4th ed.; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, D.C. Statistical Methods for Psychology, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Belmont, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Cohen, P.; Chen, S. How big is a big odds ratio? Interpreting the magnitudes of odds ratios in epidemiological studies. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 2010, 39, 860–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobucci, D. Mediation analysis and categorical variables: The final frontier. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 582–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Methodology in the social sciences; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, G. The new statistics: Why and how. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKinnon, D.P. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis; Multivariate applications; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS: (and Sex and Drugs and Rock “n” Roll): Deakin University Library Search, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, C.J. An effect size primer: A guide for clinicians and researchers. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2009, 40, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morelli, M.; Bianchi, D.; Baiocco, R.; Pezzuti, L.; Chirumbolo, A. Not-allowed sharing of sexts and dating violence from the perpetrator’s perspective: The moderation role of sexism. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 56, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollis, D. The power of feminist pedagogy in australia: Vagina shorts and the primary prevention of violence against women. Gend. Educ. 2017, 29, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, D.E.; Beck, K.; Kerr, M.H.; Shattuck, T. Psychosocial correlates of dating violence victimization among latino youth. Adolescence 2005, 40, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holt, T.J.; Bossler, A.M.; Malinski, R.; May, D.C. Identifying predictors of unwanted online sexual conversations among youth using a low self-control and routine activity framework. J. Contemp. Crim. Justice 2016, 32, 108–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, A.; Henry, N. Sexual Violence in a Digital Age; Palgrave studies in cybercrime and cybersecurity; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, E.; Leung, R.; Baksheev, G.; Day, A.; Toumbourou, J.W.; Miller, P.; Kremer, P.; Walker, A. Violence prevention and intervention programmes for adolescents in australia: A systematic review. Aust. Psychol. 2016, 51, 206–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, A.; Peters, T. NAPCAN’s “growing respect”: A whole-of-school approach to violence prevention and respectful relationships. Redress 2011, 20, 16. [Google Scholar]

- George, A.S.; Amin, A.; de Abreu Lopes, C.M.; Ravindran, T.K.S. Structural determinants of gender inequality: Why they matter for adolescent girls’ sexual and reproductive health. BMJ 2020, 368, l6985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Madigan, S.; Ly, A.; Rash, C.L.; Van, J.O.; Temple, J.R. Prevalence of multiple forms of sexting behavior among youth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2018, 172, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| DoS Subscale | M | (SD) | Range (Min, Max) | N | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dichotomized Subscales | |||||

| Low I-Position | 20.47 | (4.17) | (7, 26) | 187 | |

| High I-Position | 31.00 | (4.16) | (27, 42) | 213 | |

| Low Fusion | 8.65 | (1.82) | (5, 12) | 197 | |

| High Fusion | 15.24 | (2.89) | (13, 25) | 203 | |

| Continuous Subscales | |||||

| I-Position (Female) | 25.93 | (7.26) | (7, 42) | 272 | 0.80 |

| I-Position (Male) | 28.48 | (7.08) | (9, 42) | 127 | |

| Fusion (Female) | 11.44 | (3.86) | (5, 25) | 272 | 0.60 |

| Fusion (Male) | 12.87 | (4.63) | (5, 25) | 127 |

| Predictor | Outcome | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Variables | |||

| Coerced Unwanted Sexting | Willing Unwanted Sexting | |||

| b (S.E) | Odds Ratio [95% CI] | b (S.E) | Odds Ratio [95% CI] | |

| Gender 1 | 1.84 (0.53) | 6.30 [2.22, 17.81] ** | 1.05 (0.28) | 2.85 [1.64, 4.93] ** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Laird, J.; Klettke, B.; Clancy, E.; Fuelscher, I. Relationships between Coerced Sexting and Differentiation of Self: An Exploration of Protective Factors. Sexes 2021, 2, 468-482. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes2040037

Laird J, Klettke B, Clancy E, Fuelscher I. Relationships between Coerced Sexting and Differentiation of Self: An Exploration of Protective Factors. Sexes. 2021; 2(4):468-482. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes2040037

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaird, Jessica, Bianca Klettke, Elizabeth Clancy, and Ian Fuelscher. 2021. "Relationships between Coerced Sexting and Differentiation of Self: An Exploration of Protective Factors" Sexes 2, no. 4: 468-482. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes2040037

APA StyleLaird, J., Klettke, B., Clancy, E., & Fuelscher, I. (2021). Relationships between Coerced Sexting and Differentiation of Self: An Exploration of Protective Factors. Sexes, 2(4), 468-482. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes2040037