Abstract

Migrant and refugee women face specific health risks and challenges during the perinatal period, presenting with complex physical, psychological, and mental health issues. Compassionate antenatal and postnatal care is urgently required across Europe given how outcomes during this period determine the health wellbeing throughout a person’s life. The current study aimed to describe the perinatal health care provided to refugee and migrant women in Greece, as well as to identify the barriers to delivering quality health care to these population groups. Data were gathered via qualitative research, and via document analysis, including grey literature research. Two focus groups were convened; one with five midwives in Athens (representing NGOs in refugee camps and public maternity hospitals) and another in Crete with twenty-six representatives of key stakeholder groups involved in the perinatal care of refugees and migrant women. Desk research was conducted with in a stepwise manner comprising two steps: (a) a mapping exercise to identify organizations/institutes of relevance across Greece, i.e., entities involved in perinatal healthcare provision for refugees and migrants; (b) an electronic search across institutional websites and the World Wide Web, for key documents on the perinatal care of refugee and migrant women that were published during the 10-year period prior to the research being conducted and referring to Greece. Analysis of the desk research followed the principles of content analysis, and the analysis of the focus group data followed the principles of an inductive thematic analysis utilizing the actual data to drive the structure analysis. Key findings of the current study indicate that the socioeconomic status, living and working conditions, the legal status in the host country, as well as providers’ cultural competence, attitudes and beliefs and communication challenges, all currently represent major barriers to the efficient and culturally appropriate provision of perinatal care. The low capacity of the healthcare system to meet the needs of women in these population groups in the context of maternal care in a country that has suffered years of austerity has been amply recorded and adds further contextual constraints. Policy reform is urgently required to achieve cultural competence, to improve transcultural care provision across maternity care settings, and to ensure improved maternal and children’s outcomes.

1. Introduction

The need to develop ‘migrant-sensitive healthcare systems’ has been raised as a key global health and public health issue [1] with primary care representing the optimal setting to effectively and efficiently tackle the existing inequity in terms of access to health care provision [2,3]. Recently, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) underlined that one of the most vulnerable groups requiring a prompt, coordinated, and effective response [4] are all migrant and refugee women with an emphasis on pregnant and lactating women, adolescent girls and early married girls, sometimes having newborn babies themselves [5]. This priority is inextricably tied to the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3, and particularly subgoal 3.8 (Universal Health Coverage, UHC) and SDG5 (Achieving gender equality and empowering all women and girls) and of the UN. The challenge for healthcare professionals, systems, and governments alike, is how to best ensure the population groups who are most vulnerable and most neglected are included and prioritized; ensuring the best possible for this groups contributes to individual, but also societal resilience. This specific, most vulnerable, group of migrant and refugee women faces specific health risks and challenges during the perinatal period as they present a complex physical, psychological, and mental state of health. European policies mandate that all “States are responsible for guaranteeing refugee and asylum-seeking women’s full access to health care assistance, reproductive health services, and psychological assistance, considering their specific needs and eliminating the legal and practical barriers that prevent them from accessing the health care system”. Moreover, compassionate antenatal and postnatal care and compassionate health professionals have been warranted to serve refugees in the most appropriate manner [6].

Greece is a country still struggling to comply with these mandates. Within a two-year period (2015–2017) more than one million people, primarily fleeing conflict in Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq, entered Greece [7], including an approximate 21% of women and a high number of pregnant ones [7,8]. Despite this high influx of refugee women, Greece, as well many other European countries, face many difficulties in ensuring the best possible access to the appropriate healthcare services for refugee mothers and newborns. Greece’s Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX) score for the health of migrants (http://www.mipex.eu/greece) (accessed on 5 October 2018) reveals limited availability of services and high out-of-pocket payments. The overall care pathway seems to be complicated when it comes to perinatal care in Greece. Perinatal services for refugee/migrant populations are provided in a number of different ways: Antenatal Care (ANC) and Postnatal Care (PNC) services are available by appointment in the public health system; however, accessing appointments is often difficult for refugee/migrant women. The National Health Operations Center facilitates the appointment process in the public system, but cannot force hospitals and clinics to provide timely appointments. Notably, although refugee/migrant women are meant to go directly to the closest hospital/clinic in their area, many women are directed by the local hospitals/clinics to maternity hospitals due to the low capacity to meet their needs. In fact, although in theory all hospitals should be equipped to carry out normal deliveries, cases are often referred to the tertiary-level maternity hospitals due to lack of staff, equipment, and interpreters. On the other hand, the medical staff have expressed concerns about not attending refugee and migrant women prior to delivery, not maintaining complete medical records and having access to the woman’s medical history, and not sharing a common language in which to communicate with women during delivery [9,10,11]. Without antenatal care, maternal and fetal complications are more likely to remain undiagnosed and to compromise care during childbirth and in the postnatal period too, thus, leading to higher rates of maternal mortality, severe maternal morbidity, and neonatal morbidity [12,13]; all these aspects adversely contribute to overall maternal and children’s outcomes, whereas the importance of said outcomes is paramount for the development of the child. Critically, there are currently no national recommendations or professional guidelines regarding the perinatal health care and the delivery thereof to female migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers, and this affects both the quality of care and the woman/patient–healthcare professional (midwife, doctor, nurse, etc.) interaction.

The recent financial crisis and the austerity measures have substantially weakened the healthcare system, with depleted resources compromising its resilience and overall capacity. This has exacerbated these issues resulting in a dysfunctional primary healthcare sector, with many cutbacks in healthcare services to vulnerable groups [14,15,16]. These national circumstances have resulted in an initiative to launch a European capacity-building collaborative project (ORAMMA Operational Refugee And Migrant Maternal Approach) in three European countries (Greece, Netherlands, and the United Kingdom) under the auspices of the European Commission with funding by the 3rd Health Programme of the Consumers, Health, Agriculture and Food Executive Agency (CHAFEA) (ID 738148). ORAMMA aimed to develop, pilot implement, and evaluate an integrated and cost-effective approach on safe motherhood provision for migrant and refugee women, taking into consideration best practices in the field of compassionate maternal and perinatal health care, as well as the special risks and characteristics of the pregnant refugees and their newborns.

The current paper is part of the ORAMMA project and aims to present the grey literature and the stakeholders’ views on the perinatal health care provided to refugee and migrant women in Greece, as well as the barriers faced by the service providers and service users in the provision and access to quality health care.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review of the Literature

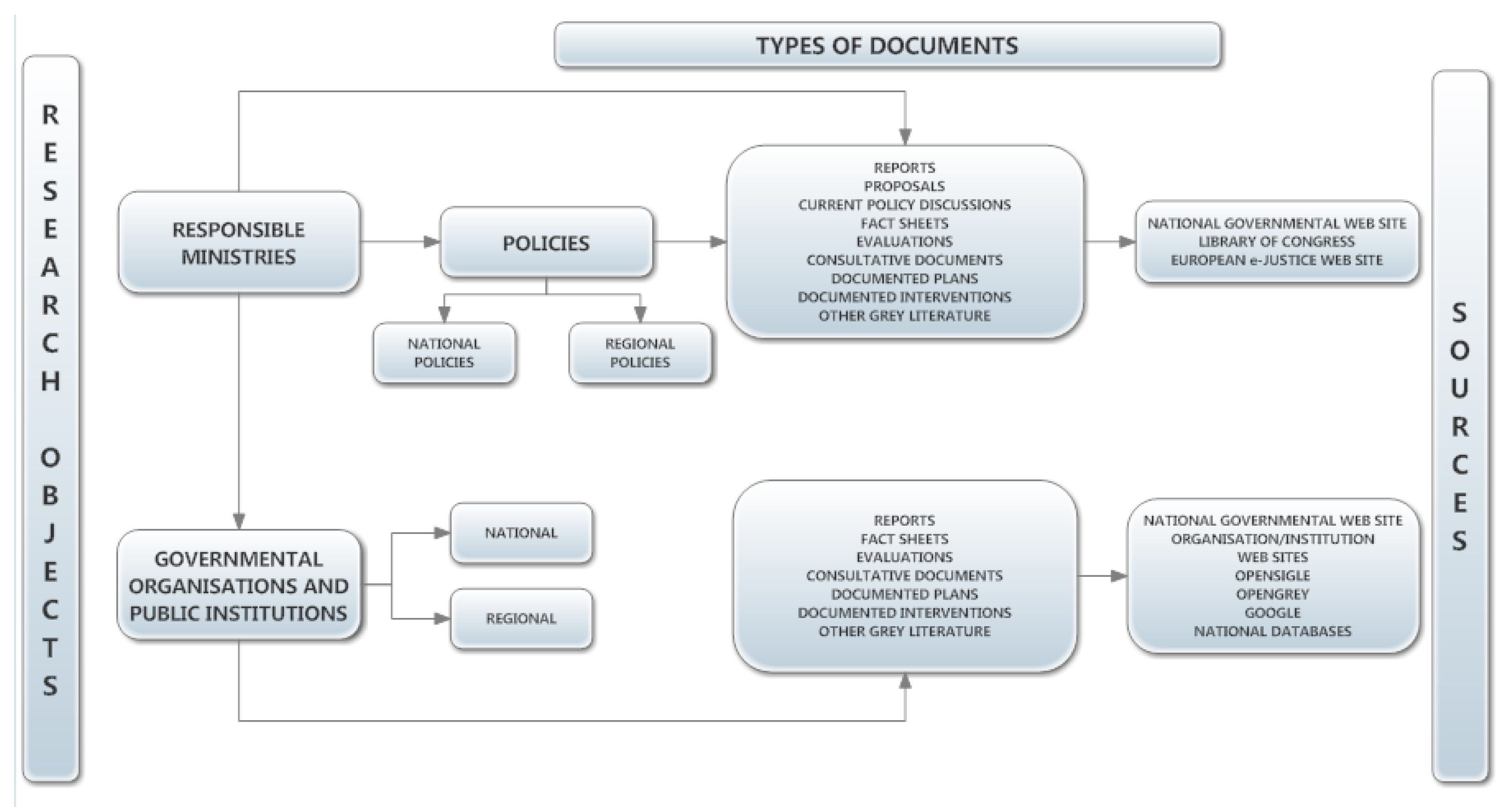

Desk research was carried out to identify relevant documents and grey literature on the topic of interest. The desk research involved a stepwise approach comprising two consecutive steps: (a) a mapping exercise to identify organizations/institutes of relevance across Greece, i.e., entities involved in perinatal healthcare provision for refugees and migrants; (b) an electronic search across institutional websites and the World Wide Web, for key documents on the perinatal care of refugee and migrant women that were published during the 10-year period prior to the research being conducted and referring to Greece. To identify the appropriate governmental organizations/institutes, the adopted search method was primarily desk-based digital browsing, using governmental web-based sources (i.e., Figure 1). The digital database Library of Congress (http://www.loc.gov/law/help/guide/nations.php) (accessed on 5 October 2018) was utilized. Personal contact with each ministry/department was established complementarily in the form of telephone or e-mail communication. As for the non-governmental organizations (NGOs), the search included both national and regional/local-level organizations. Local organizations were represented within the frame of their umbrella organization. The search included all NGOs involved in the design, provision, and evaluation of perinatal health care services for migrant/refugee women. These included, but were not limited to, professional associations and learned societies of primary care professionals such as those of midwives, general practitioners (GPs) and family physicians, social workers, etc. NGOs offering volunteer preventive or curative medical services to female migrants such as “Doctors of the World” and “Red Cross”, female or migrant-oriented NGOs offering assistance to female migrants “Local or Regional Migrant Unions”, “Association of Syrians”, etc., NGOs offering counseling, social support, guidance, education, etc., to female migrants such as “community social services” were all included. The electronic search was then conducted in both the English and the local language (Greek) using the institutional websites in Greece as well as EU-wide grey literature web sites (e.g., OPENgrey, OPENsigle, GOOGLE databases). The aim of the search was to identify key documents with information on the perinatal care for migrant/refugee women. The electronic search used the following three groups of search terms in different combinations: {“refugee”, “asylum seeker” “migrant”, “immigrant”}, {“maternal”, “perinatal”, “prenatal”, “postnatal”, “antenatal”, “pregnant”}, {“care”, “treatment”, “management”}. Eligibility of the identified documents was judged based on the following criteria: (1) year of publication/reference (last 10 years/2008 until 2017), (2) languages (English, Greek), (3) geographical coverage (Greece), (4) type of document [reports (e.g., pre-prints, preliminary progress and advanced reports, technical and statistical reports, etc.], theses, conference proceedings, official documents (e.g., government reports and documents), pre-prints and post-prints of articles, editorials, opinion letters, working papers, surveys, documented interventions, etc., (5) presence of search terms.

Figure 1.

Governmental resources.

2.2. Qualitative Research with Representatives of Key Stakeholder Groups

Focus group sessions were employed in combination with Participatory Learning and Action (PLA) techniques (e.g., commentary charts) as the most appropriate means for data generation in groups of participants with mixed backgrounds and different levels of language skills (e.g., migrant participants). Two focus group discussions were carried out to identify barriers of delivering efficient perinatal health care to refugee women in Greece (Athens, Crete). A sample of 5 midwives was established in Athens representing two different sectors; NGOs operating in refugee camps and the national health care system with emphasis placed on public maternity hospitals. The sample was identified through nominations by the National Public Health Organization based on the staff availability at the sites of interest during the period of the study. A sample of 20 persons was selected in Crete, using a maximum variation sampling, in order to achieve the highest representativeness of organizations/agencies involved in the perinatal care of refugee and migrant women. The following criteria were applied for the sample selection: (a) mission of organization (perinatal health care for migrant/refugee as primary or secondary mission), (b) target group of the organization (migrants/refugees among the target population), (c) type of organization (governmental and NGO), (d) population coverage (national, regional, and local). A focus group guide was developed to serve the data collection process in both sites, including four main thematic areas relevant to the perinatal health care of migrant/refugees as follows: (a) description of involvement in perinatal care of refugees/migrants, (b) prevention and intervention strategies, (c) good practices in perinatal care, (d) barriers in perinatal care. In Crete, due to the diversity in stakeholder groups and the mixed background and origin of the participants, commentary charts were also developed to conduct a “Strengths-Weaknesses-Opportunities-Threats” (SWOT) analysis of the perinatal healthcare provision in Greece, both from the perspective of the primary healthcare user (women/patients) and from that of the primary healthcare worker (professionals/providers). The focus group facilitators represented the scientific fields of Social Work and Midwifery (MP, MI, ES). One of them (MP) had received full training in Participatory Learning and Action (PLA) by an expert organization and already had rich experience in applying this method to various groups. All had rich experience in carrying out focus group sessions on topics relevant to health and social care.

2.3. Procedures

2.3.1. Desk Research

One researcher carried out the mapping process for relevant governmental, non-governmental organizations/institutes and trade unions in Greece (e.g., ministries of health, professional unions of midwives, GPs). The researcher employed electronic, telephone or e-mail communication, as necessary. A set of pre-defined data set was extracted on the identified organizations/institutes and put into template (A) in Table A1 (name of institute, position of representative, contact details, web-site info, mission related to the subject of interest). The electronic search followed a step-wise search strategy to ensure that all information relevant to the topic of interest would be captured in the final portfolio. Two researchers carried out the electronic search. A third researcher was in place for reconciliation purposes. The process involved an initial broad search for information on the perinatal care of the general female population, using combinations from the two groups of key terms {“maternal”, “perinatal”, “prenatal”, “postnatal”, “antenatal”, “pregnant”}, {“care”, “treatment”, “management”}. A second search was employed to make the investigation more targeted towards the migrant populations. This search included the additional terms from the third group of search terms {“refugee”, “asylum seeker”, “migrant”, “immigrant”}. All the information fulfilling the eligibility criteria was extracted and put into the template (B) in Table A2. An English abstract was provided for all documents, as well as for those in local language.

2.3.2. Qualitative Research

The two focus groups were held at the offices of Athens Midwives Association (Athens) and the School of Health, Hellenic Mediterranean University (Crete). Both sessions were carried out at mid-2017. The focus group guide was distributed to the study participants prior to the session for purposes of own preparation. Informed consent was received by all the participants prior to participation. The sessions lasted approximately 1 h and 30 min each and involved four phases: (a) introduction of participants, (b) individual response to three items included in the focus group guide (involvement in perinatal care; prevention and intervention strategies; good practices), (c) small group discussions involving 7–9 participants (worked out a SWOT analysis of perinatal health care from the perspectives of primary health care (PHC) users and providers in rotated fashion), and (d) plenary discussion (to enable presentation of key points of small group discussions and further feedback and insights).

2.4. Data Analysis

The literature was organized on the basis of the type of document it corresponded to. The analysis followed the principles of content analysis and was driven by the study research questions as follows: what are the barriers of delivering efficient perinatal care to refugee/migrant women? The qualitative research on the other hand generated two data sets: one from the focus groups discussions and another from the PLA commentary charts. The focus group discussions were transcribed and then both the PLA charts and the transcripts of the sessions were reviewed using the principles of an inductive thematic analysis about key barriers of efficient perinatal care. In our study data saturation was defined as the point where the core researchers determined that no new thematic codes were identified by three individual representatives of each organizational group invited to participate in the focus groups including (a) healthcare authorities, (b) social care authorities, (c) professional groups of service providers and interpreters, (d) migrant/refugees/asylum seeker groups. To meet this objective we secured three or more representative organizations per field of activity. We then compared the data generated by the groups internally first (between members of each group) and then externally (between groups). We are confident that data saturation was achieved as the analysis reached a point where the codes and themes were comprehensive. In addition, confirmatory cross-comparisons were conducted between the data generated in the focus group discussions and those recorded in the commentary charts. This combined assessment offered an ideal opportunity to methodically establish and analyze the concept of saturation from both the transcript analysis and chart review perspective within a qualitative study. These methods were conducted post hoc with the data set.

3. Results

3.1. Description of Literature

A total of 40 documents (Table 1) were located through the web, which were published within a 10-year period in English and Greek, focusing on the perinatal health of migrant, refugee, and asylum seeking women in Greece. Most of the documents were scientific papers either research or policy oriented while a large number of documents were reports of EU committees and networks on migrant issues or annual reports of international NGOs active in health issues of vulnerable populations (e.g., Médecins du Monde, MdM). The list is not exhaustive but it offers the vast amount of written information regarding the topic of interest in our country and a full picture of current trends in terms of access, availability, and quality of perinatal health care in Greece.

Table 1.

Documents identified through the electronic search.

3.2. Focus Group Participant Profile

A total of twenty-six organizations/institutes were represented in the focus group session in Crete (see details in Table 2). These organizations represented governmental authorities with health care as their main mission (e.g., regional health government, hospital administration and hospital medical departments, primary health care authorities), governmental social care authorities (e.g., regional social care administration, municipal social policy departments, community social care services), academic institutions of primary care professions (e.g., Medical School, Nursing Department, Social Work Department), professional associations/societies (e.g., medical, nursing, midwifery, lawyer associations), NGOs with migrants as their main target group (e.g., international migrant organization), NGOs organizations with a focus on the health of vulnerable groups as their main target mission (e.g., Red Cross) and local migrant groups/communities (e.g., Syrian community), local interpreting and cultural mediation services offered by individuals at voluntary level or via subcontracting to local/regional authorities.

Table 2.

Organizations represented in the focus group discussion in Crete.

3.3. Main Findings

3.3.1. Barriers Related to Service Users

Following an analysis of the grey literature (Table S1) and focus group discussions (Table 3), the following major barriers to perinatal care for migrants/refugees and asylum seekers in Greece were identified:

Table 3.

Summary of study findings with selected quotation.

- (a)

- Language as a barrier in access to perinatal care: Many women experience difficult family situations such as domestic violence and controlling relationships which are not easy to share with cultural mediators and/or interpreters. This crucial factor excludes women from seeking and/or accessing the necessary care, thus, affecting both their own and the fetus’s health, and maternal/newborn outcomes. Furthermore, health service providers rely excessively on “informal” interpretation coming from family environment and friends, which compromises both the quality of interpretation and confidentiality. Indeed, informal interpreters’ lack of knowledge of medical terminology may result in women being subjected to medical interventions they did not consent to, without any of the procedures being explained or understood. Medical interpreters and trained maternity peer supporters need to be available for women who are at the perinatal phase. It is also recommended that culturally appropriate educational materials should be distributed to pregnant and childbearing refugees, including information on key symptoms and health complications. Furthermore, women may be less likely to be willing to disclose information that may not be treated confidentially, either because of a relationship of a personal nature with the informal interpreter and/or because of the lack of training in terms of Code of Conduct for interpreters to informal interpreters from the wider ethnic and cultural community these women belong in.

- (b)

- Cultural barriers in woman-healthcare professional (e.g., patient-doctor) communication: Communication restrictions worsen due to limitations of understanding different traditions related to pregnancy and childbirth. The provider’s gender can be a barrier in help-seeking behaviors for those women whose tradition or religion does not allow interaction with men. Culturally appropriate service, with high cultural understanding and informed consent practices, can encourage women to utilize the available maternity care.

- (c)

- Financial incapacity, irregularity, and low sense of safety preventing safe perinatal practices: The illegal employment status that many refugee women have, results on relying on employers’ intention to afford them maternity leave to be able to access the care they need. Newly arrived refugees are commonly unemployed or in best cases are low-paid or have occasional employment. Insecurity, as well as ignorance of labor and residency rights, is a major barrier for women, who frequently ignore symptoms of illness or other health care needs or postpone seeking care. Women are unable to attend appointments or meet their needs due to the legal status and the associated restrictions in their rights and entitlements to welfare, low-paid work, and controlling behaviors within the family culture. Refugee women, regardless of their migrant status or regularity, should be informed about their rights in the country of destination prior to pregnancy, including their right to a safe perinatal journey.

- (d)

- General disappointment with the health care system: Refugee women frequently arrive in the country of destination with unrealistic expectations of its people and services, either because they were intentionally misinformed by those who arranged their transfer or because of excessive optimism combined with lack of understanding of the policies and capacity of the country of destination. The difficulty of obtaining legal status confirming they are entitled to receive care and challenges in accessing services turns enthusiasm into disappointment, which frequently results in emotional reactions such as withdrawal from trying to negotiate their rights. To prevent emotional burnout and the psychological consequences of distress and withdrawal, refugee women should be given culturally appropriate assistance in navigating to local services from the moment they arrive in their host country. Trying to ensure that refugee women understand how to navigate the healthcare system can help to reduce delays in seeking health care and receiving adequate treatment.

- (e)

- Racism victimization creates a generalized resistance and suspicion of system requirements: Refugee women are frequently subjected to racism and are sometimes humiliated by the local population. This frequently makes them feel unwelcome, preventing them from investing in the health care system and developing trusting relationships with health care providers. Mutual trust is essential for ensuring quality of care between refugee women and healthcare providers. To ensure that refugees trust the local setting, its people, and services, action to combat racism and xenophobia in local society must be enhanced.

- (f)

- High psychological distress because of migration conditions, preventing effective self-care, self-hygiene, and help-seeking: Refugee women are frequently faced with numerous challenges, which lead to high levels of psychological distress. A history of torture which entailed their urgent transfer, sex and gender-based violence due to cultural proneness, female genital mutilation (FGM), unemployment and racism, and the stress of obtaining legal status in the country of destination are among the most common factors affecting refugee mental health. Perinatal stages are also related to emotional stress and fragility, highlighting the need for specialized care. Lengthy social and psychological support should be provided to them beginning with their arrival in the country in order to prevent mental health problems.

3.3.2. Barriers Related to Service Providers

The following barriers to access, availability, and quality of perinatal care for migrants/refugees and asylum seekers in Greece were identified:

- (a)

- Low capacity to meet the health care needs of migrants in a culturally appropriate manner: Cross-cultural training and resources for health care providers appear to be missing to aid migrant women in a culturally appropriate way. In the busy primary health care environment, the lack of cultural mediators and interpreters appears to be a serious shortcoming that requires additional attention, particularly when paired with staff and resource shortages. The absence of a social and family network to aid women in adhering to therapy and care pathways is a significant shortcoming that creates many difficulties for health care providers who must work collaboratively with important others to treat serious medical issues in migrant women. Appropriate cross-cultural communication is hard to accomplish in a system that lacks resources to support the development of a culturally competent workforce. Furthermore, a lack of cross-cultural training allows for stereotyped thinking and does not promote trusting and caring relationships among health care providers and migrant women.

- (b)

- Doctor-centered and patriarchal systems of care with minimal investment in the interdisciplinary and interprofessional training of the care team: The healthcare system appears to be overly reliant on the medical doctor rather than the healthcare team, which makes it less flexible, particularly during a crisis. The healthcare team must be reinforced, and patient care must be re-distributed with tasks allocated to all team members in a balanced manner. Specific medical procedures may need to be delegated to other healthcare professionals to save time and improve quality (e.g., prescription by a midwife or nurse). Social workers and mental health professionals must be part of the team to address the various psychosocial problems that co-exist or arise as a result of the medical problem and other circumstances.

- (c)

- Lack of service integration and continuity of care: Despite migrant women’s multimorbidity, medical and psychosocial services in the community are not horizontally linked, making it more difficult for them to seek help. Bio-psychosocial assessment and treatment proves difficult, despite the fact that it is required to meet the health care needs of women holistically. In order to enhance continuity of care, particularly in this difficult-to-reach population, the lack of horizontal integration of services must be resolved through organizational changes in the PHC setting.

- (d)

- Low engagement during crisis—healthcare professional’s burnout: Many changes have occurred as a result of the financial crisis, including service mergers or closures, salary cuts, staff and equipment shortages, and this has increased the burden on health care providers. There appear to be deficient mechanisms in place to address this enormous psychological and physical burden and prevent exhaustion and even burnout, which has a significant impact on care quality. Furthermore, training and information to allow the healthcare professional to identify signs of exhaustion early and manage stress, workload and to seek care too, is urgently needed.

4. Discussion

Latest reports indicate that a high percentage of women, who arrive in Greece, will be in the reproductive age (WRA), increasing the demands for efficient and culturally appropriate perinatal care. This is the time to ask ourselves whether we have a healthcare system which is ready to meet their needs and to ensure the best possible outcomes for mothers and children alike. The current study comes is timely to offer important information on the current situation of refugee and migrant women residing in Greece whilst requiring care during the perinatal period. The evidence emerging through the literature review indicates that refugee and migrant women are confronted with a number of systemic, cultural, and provider-specific barriers, which affect the quality of the care they receive and the outcomes during the perinatal period, with potential consequences for the rest of the lives of both women and children.

The low socio-economic status of these groups, precarious working conditions and language difficulties were the most common barriers identified in the current study and were related to lower standards of care or limited choice availability in the healthcare system. This does not come as a surprise and is consistent with emerging evidence from other research teams across countries [17,18,19,20,21,22]. A recent study published by Vazquez and colleagues [23] highlighted certain immigrants’ sociodemographic characteristics as key barriers to effective care. Some key-examples included the need to pay for prescribed medication, which directly relates to impeded access to affordable care, as the low socioeconomic status of immigrants prevents them from purchasing it. The same applies in the instances where co-payments and/or even out-of-pocket payments determine the range of choices in the perinatal journey. Furthermore, precarious employment conditions- long working hours, job insecurity and lack of formal contracts were identified as a barriers to accessing health care, particularly when combined with factors such as geographical distance compromising accessibility, incompatible opening hours and fees to access care.

Other major barriers identified in the current study were related to cultural challenges. In many studies culture has been described as the source of difficulties with using maternity care services as well as because of language limitations. Lyberg and colleagues [24] report that midwives and nurses perceived “Health Challenges” and “Cultural Challenges” as major barriers in managing and supporting prenatal and postnatal migrant women in Norway. “Health challenges” included differing expectations of support, diversity in education and knowledge, emotional pain, and physical consequences for the fetus, delivery and the newborn baby. Similarly, Otero-Garcia and colleagues [25] report under-utilization of family planning services was believed to be associated with cultural differences and gender inequality.

The lack of cultural competence on the part of the providers was a serious obstacle in healthcare contacts of migrants, which emerged from the current study. A number of studies have identified the lack of cultural competence and skills [26], the lack of understanding of cultural differences and the limited insight into the differences in migrants’ childbirth practices [27]. Degni and colleagues [28] report that the Somali women’s cultural traditions and religious beliefs, which are critical for the care they can receive for childbirth and in the antenatal and postnatal period, were unfamiliar to physicians in clinics. Male physicians found it insulting when the Somali woman refused to come into the consultation because the physician was a male, and even in the cases that they did, they could not comprehend they would not shake hands to avoid physical contact because the physician was male. In a study of Puthussery and colleagues. [29], stereotypical views of professionals towards ethnic minority women influenced clinical decision-making and clinical practice. Limited language competence and communication skills were also shown to be related to “lower standards of care or less choice” [30,31]. Factors of communication, such as limited ability to articulate either care needs or care advice, were interpreted as the main barrier to access of immigrant African women in UK [31] and were viewed as a source of increased stress for midwives in the study of Tobin and Lewless [32].

Another important barrier of effective management of maternity needs that has been evident in the current study was the low capacity of services. This is evident in many previous studies in the Greek setting [22,33]. Similarly, in Binder and colleagues [31] the lack of consistent clinical guidelines, insufficient staff, and poor interpreter services prevented healthcare professionals from being able to deliver the best possible maternal health care. In addition, the lack of community based services, outreach programs and gateways services was found to contribute to the provision of low quality service to pregnant women. For example, in Tobin and Lewless [32] findings revealed the lack of adequate services (parenting education, psychiatric care, or counseling) and its impact on effective care. In line with this, the study of Kolak and colleagues [34] underlined the importance of outreach activities and other adult education facilities as an opportunity to individualize counseling according to culture, gender, group, and age. Low service capacity was also identified by Falla and colleagues. [35] in a survey carried out in six European countries (Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, and the UK), which showed that interpreters and translated material were common in some EU countries but very rare in some other countries.

4.1. Implications for Research and Practice

According to World Health Organization (WHO), all women have the right to access to appropriate communities maternity care services and the governments should ensure their access to maternity care services. Ensuring quality health for women and newborn is a matter of equity, human rights, and is a way of achieving the SDGs and safeguarding the resilience and growth of our societies. The current study offers important insight on efficient ways to address existing barriers to quality maternity care for refugee women who seek care in community settings of Greece. What we have learned from this research is that a number of psychosocial and cultural issues, financial constraints, administrative problems, health coverage issues, low health literacy, language barriers, fear of authorities and previous bad experience, affect refugee women’s health during maternity and restrict their access to quality health care. Efficient ways to deal with the complex needs of these women include (a) promoting effective communication and interaction through competent bilingual cultural mediators, (b) recruiting empathic, compassionate, culturally competent healthcare providers, (c) establishing flexible and responsive services, following culturally sensitive clinical practices, (d) promoting women’s and their families’ awareness and health literacy, and (e) ensuring sufficient resources for interprofessional training of all professionals involved in the care of women, including in the establishment of Codes of Conduct and Codes of Ethics, including for interpreters. We must ensure that well-designed health care services meet the heterogeneous needs of these women. What comes out of the results of this research is that we need family-centered and culturally-sensitive perinatal care and clinical approaches, which are grounded on self-determination, respect women’s values, and preferences and incorporate their culturally-derived expectations. Our research findings underline the need to facilitate safe spaces and patient-centered processes with trusting and genuine interaction between the multidisciplinary team, the women and their families. We need empathy in the clinical interaction to help women express their fears and worries and seek help for personal or family adversities. Most importantly, our findings indicate the need to utilize family, community and peer support networks during all the perinatal stages, which has been shown to offer women a feeling of security, increase their confidence and has a positive impact on their health outcomes.

We also need to acknowledge the fact that the refugee crisis of recent years has increased the pressure for the national health system, which will be constantly challenged to respond to changing needs and new migration patterns. As this population is hard-to reach, it is likely that their journey to maternity in the host country is under-investigated. More systematic research with alternative research methods and participatory approaches, across the various perinatal stages, is necessary to deepen into the unique, complex and absolute nature of the refugees’ experience. Such research will fill a huge gap in current knowledge and will promote evidence-informed policies for quality maternity care.

4.2. Study Limitations

There are certain limitations related to this study that need to be acknowledged. Although the desk review and document analysis was based on a rigorous research strategy with concrete selection criteria and alternative data collection procedures, we should not ignore the risk of missing information due to organizations’ unpreparedness to share documents or offer them publicly in their webpages. We have tried to mitigate this risk through directly contacting selected organizations but this may not be considered as an exhaustive exercise. Likewise, certain information might have been missed due to limiting the period of interest for the literature review to the 10-year mark prior to the study conduct. However, this period offers a recent picture of the country situation and corresponds to the time that the financial crisis started in Greece, when the country situation changed dramatically. So, this is a very specific period of time, with certain impact on migrants’ and refugees health, access and quality of health services, but also on the same aspects for all persons seeking care, as well as a period of protracted pressure and challenges for the personnel providing care; the health and social care workforce have had to compensate for limited resources, whilst experiencing uncertainty and exhaustion.

From a methodological perspective, although opinions differ on optimal sizes, focus groups are generally not large, varying from eight to twelve people [36]. In our study, the basic element was the participatory aspect, which used subgroup discussions and interactive tools (e.g., commentary charts) on topics that were well-defined prior to carrying out a focus groups. In such cases, the expected number of participants has been noted to be larger, ranging from three to fourteen, while others note that the size should reflect the characteristics of participants as well as the topics being discussed [37]. Nevertheless, we need to acknowledge the fact that our focus group was larger than expected, therefore running the risk of some participants monopolizing conversations, crowding out other viewpoints, etc. Last but not least, the small number of participants in the study restricts generalizability of current findings, while the fact that the participants were drawn from two regions of Greece implies that we cannot claim that the findings apply to other parts of the country. Especially in the case of the first focus group, the sample was identified by the National Public Health Organization based on the staff availability and this may have introduced a selection bias, implying that the conclusions drawn from this study may not reflect the overall population of interest.

5. Conclusions

The current study has identified a number of barriers to providing effective maternity care for refugee and migrant women in Greece. Evidence indicates that the living and working conditions of these groups, as well as their legal status in the host country, are key determinants of the women’s health status, potentially affecting both their children and their families too, and they considerably influence their health-related, including health-seeking, behavior during the perinatal period and well beyond that. Among other, the current study comes to verify the huge importance of service providers’ cultural competence for health care delivery. It also shows that the attitudes and beliefs held by health care providers in Greece as well as their low understanding of cultural differences limit their effectiveness and increase their workload, frustration, and helplessness. Communication difficulties was also shown to be a serious obstacle during delivery of maternity services. Last but not least, current evidence indicates that the Greek healthcare system lacks the capacity to meet the needs of these women during maternity. Lack of interpretation services, absence of practice guidelines for transcultural care and culturally-adapted material seem to be common in maternity services. Individualized outreach programs and gateway services tailored to increasing access to services, helping new migrants learn how to navigate health services, and providing training in cultural competence for midwives and other health providers are needed. Policy reforms are necessary to achieve cultural competence and improve transcultural care in maternity care. The development of a viable community-based maternity service that is crucial to providing continuity of care for child-bearing women and needs to be taken into account in future policy reforms.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/sexes2040036/s1, Table S1: Grey literature on migrant and refugee maternity health and social care in Greece.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.V. and M.P.; methodology, M.P., M.I., E.S., E.P. and V.V.; formal analysis, M.P., M.I., E.S., E.P. and V.V.; investigation, M.P., M.I. and E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P., M.I., E.S., E.P. and V.V.; writing—review and editing, M.P., M.I., E.S., E.P. and V.V.; project administration, E.S. and M.I.; funding acquisition, M.P. and V.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Commission under the European Union’s Health Programme (2014–2020) (project ‘738148/ORAMMA).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval was granted by institutional committees.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants of the current study for their contribution.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Abbreviations

| UNHCR | United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| UHC | Universal Health Coverage |

| MIPEX | Migrant Integration Policy Index |

| ANC | Antenatal Care |

| PNC | Postnatal Care |

| NGOs | Non-governmental organizations |

| MdM | Médecins du Monde |

| FGM | Female genital mutilation |

| GPs | General practitioners |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Template for organizations/institutes appointed to address migrant health and social care.

Table A1.

Template for organizations/institutes appointed to address migrant health and social care.

| No | Name of Organization | Name and Position of Contact Person | Contact Info | Website | Mission |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | |||||

| 2 | |||||

| 3 | |||||

| 4 | |||||

| 5 | |||||

| 6 | |||||

| 7 | |||||

| 8 |

Table A2.

Template for grey literature on migrant health and social care (1) Document number; (2) Docu-ment title; (3) Document type; (4) Year of publication; (5) Developer; (6) Brief description; (7) Ref-erence to Greece/perinatal issues.

Table A2.

Template for grey literature on migrant health and social care (1) Document number; (2) Docu-ment title; (3) Document type; (4) Year of publication; (5) Developer; (6) Brief description; (7) Ref-erence to Greece/perinatal issues.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | ||||||

| 3 | ||||||

| 4 | ||||||

| 5 | ||||||

| 6 | ||||||

| 7 | ||||||

| 8 |

References

- WHO. How Health Systems Can Address Health Inequities Linked to Migration and Ethnicity; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010; Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/127526/e94497.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2017).

- Baum, F.E.; Bégin, M.; Houweling, T.A.; Taylor, S. Changes not for the fainthearted: Reorienting health care systems toward health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 1967–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, F.; Legge, D.G.; Freeman, T.; Lawless, A.; LaBonte, R.; Jolley, G.M. The potential for multi-disciplinary primary health care services to take action on the social determinants of health: Actions and constraints. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Refugee Agency; United Nations Population Fund; Women’s Refugee Commission. Initial Assessment Report: Protection Risks for Women and Girls in the European Refugee and Migrant Crisis—Greece and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland; UNFPA: New York, NY, USA; Women’s Refugee Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; p. 6. Available online: http://eeca.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/GBV-Assessment-Greece-Macedonia.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2017).

- European Parliament. Female Refugees and Asylum Seekers: The Issue of Integration; DG For Internal Policies; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2016; Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/supporting-analyses (accessed on 5 October 2018).

- Florian, L.; Young, K.; Rouse, M. Preparing teachers for inclusive and diverse educational environments: Studying curricular reform in an initial teacher education course. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2010, 14, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. Operational Portal, Refugee Situations, Mediterranean Situations, Greece. 2020. Available online: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean/location/5179 (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- UNHCR. Nationality of Arrivals to Greece, Italy, and Spain. January–December 2015. 2016. Available online: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/46811 (accessed on 3 June 2018).

- Malakasis, C.H. Migrant Maternity Care in Athens, Greece, 2016–2017; A Policy Report; Cadmus, European University Institute Research Repository: Fiesole, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shortall, C.K.; Glazik, R.; Sornum, A.; Pritchard, C. On the ferries: The unmet health care needs of transiting refugees in Greece. Int. Health 2017, 9, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, H.M.; Wallis, N. Maternity care for refugees living in Greek refugee camps: What are the challenges to provision? Birth 2020, 48, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson-Helm, M.; Teede, H.; Block, A.; Knight, M.; East, C.; Wallace, E.M.; Boyle, J. Maternal health and pregnancy outcomes among women of refugee background from African countries: A retrospective, observational study in Australia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Improving the Health Care of Pregnant Refugee and Migrant Women and Newborn Children; Technical Guidance; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018; Volume 52. [Google Scholar]

- Kentikelenis, A.; Papanicolas, A. Economic crisis, austerity and the Greek public health system. Euro J. Public Health 2012, 22, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionis, C.; Symvoulakis, E.K.; Markaki, A.; Vardavas, C.; Papadakaki, M.; Daniilidou, N.; Souliotis, K.; Kyriopoulos, I. Integrated primary health care in Greece, a missing issue in the current health policy agenda: A systematic review. Int. J. Integr. Care 2009, 9, e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niakas, D. Greek economic crisis and health care reforms: Correcting the wrong prescription. Int. J. Health Serv. 2013, 43, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakaki, M.; Ratsika, N.; Pelekidou, L.; Halbmayr, B.; Kouta, C.; Lainpelto, K.; Solinc, M.; Apostolidou, Z.; Christodoulou, J.; Kohont, A.; et al. Migrant domestic workers’ experiences of sexual harassment: A qualitative study in four EU countries. Sexes 2021, 2, 272–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouta, C.; Pithara, C.; Apostolidou, Z.; Zobnina, A.; Christodoulou, J.; Papadakaki, M.; Chliaoutakis, J. A qualitative study of female migrant domestic workers’ experiences of and responses to work-based sexual violence in Cyprus. Sexes 2021, 2, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakaki, Μ.; Chliaoutakis, J. Sexual Harassment Against Female Migrant Domestic Workers; WHO Public Health Aspects of Migration in Europe (PHAME Newsletter); WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016; pp. 10–11. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/321806/PHAME-Newsletter-issue-10-en.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Mechili, E.-A.; Angelaki, A.; Petelos, E.; Sifaki-Pistolla, D.; Chatzea, V.-E.; Dowrick, C.; Hoffmann, K.; Jirovsky, E.; Pavlic, D.R.; Dückers, M.; et al. Compassionate care provision: An immense need during the refugee crisis: Lessons learned from a European capacity-building project. J. Compassionate Health Care 2018, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fair, F.; Soltani, H.; Raben, L.; van Streun, Y.; Sioti, E.; Papadakaki, M.; Burke, C.; Watson, H.; Jokinen, M.; Shaw, E.; et al. Midwives’ experiences of cultural competency training and providing perinatal care for migrant women a mixed methods study: Operational Refugee and Migrant Maternal Approach (ORAMMA) project. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lionis, C.; Papadakaki, M.; Saridaki, A.; Dowrick, C.; O’Donnell, C.; Mair, F.S.; Muijsenbergh, M.V.D.; Burns, N.; de Brún, T.; de Brún, M.O.; et al. Engaging migrants and other stakeholders to improve communication in cross-cultural consultation in primary care: A theoretically informed participatory study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, M.L.; Vargas, I.; Jaramillo, D.L.; Porthe, V.; Lopez-Fernandez, L.A.; Vargas, H.; Bosch, L.; Hernandez, S.S.; Azarola, A.R. Was access to health care easy for immigrants in Spain? The perspectives of health personnel in Catalonia and Andalusia. Health Policy 2016, 120, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyberg, A.; Viken, B.; Haruna, M.; Severinsson, E. Diversity and challenges in the management of maternity care for migrant women. J. Nurs. Manag. 2011, 20, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otero-Garcia, L.; Goicolea, I.; Sánchez, M.G.; Barbero, B.S. Access to and use of sexual and reproductive health services provided by midwives among rural immigrant women in Spain: Midwives’ perspectives. Glob. Health Action 2013, 6, 22645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadakaki, M.; Petridou, E.; Petelos, E.; Germeni, E.; Kogevinas, M.; Lionis, C. Management of victimized patients in greek primary care settings: A pilot study. J. Fam. Violence 2014, 29, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliadou, M.; Papadakaki, M.; Sioti, E.; Giaxi, P.; Leontitsi, E.; Petelos, E.; Van der Muijsenbergh, M.; Tziaferi, S.; Mastroyannakis, A.; Vivilaki, V.G. Addressing mental health issues among migrant and refugee pregnant women: A call for action. Eur. J. Midwifery 2019, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degni, F.; Suominen, S.B.; Essén, B.; El Ansari, W.; Vehviläinen-Julkunen, K. Communication and cultural issues in providing reproductive health care to immigrant women: Health care providers’ experiences in meeting somali women living in Finland. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2011, 14, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthussery, S.; Twamley, K.; Harding, S.; Mirsky, J.; Baron, M.; Macfarlane, A. ‘They’re more like ordinary stroppy British women’: Attitudes and expectations of maternity care professionals to UK-born ethnic minority women. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2008, 13, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, S.M.; O’Keeffe, F.M.; Clarke, A.T.; Staines, A. Cultural diversity in the Dublin maternity services: The experience of maternity service providers when caring for ethnic minority women. Ethn. Health 2008, 13, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, P.; Borné, Y.; Johnsdotter, S.; Essén, B. Shared language is essential: Communication in a multiethnic obstetric care setting. J. Health Commun. 2012, 17, 1171–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, C.L.; Murphy-Lawless, J. Irish midwives’ experiences of providing maternity care to non-Irish women seeking asylum. Int. J. Women’s Health 2014, 6, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadakaki, M.; Lionis, C.; Saridaki, A.; Dowrick, C.; De Brún, T.; Brún, M.O.-D.; O’Donnell, C.; Burns, N.; Van Weel-Baumgarten, E.; Muijsenbergh, M.V.D.; et al. Exploring barriers to primary care for migrants in Greece in times of austerity: Perspectives of service providers. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2017, 23, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolak, M.; Jensen, C.; Johansson, M. Midwives’ experiences of providing contraception counselling to immigrant women. Sex. Reprod. Health 2017, 12, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falla, A.M.; Veldhuijzen, I.K.; Ahmad, A.A.; Levi, M.; Richardus, J.H. Limited access to hepatitis B/C treatment among vulnerable risk populations: An expert survey in six European countries. Eur. J. Public Health 2016, 27, 302–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Robson, C. Real World Research; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bloor, M.; Frankland, J.; Thomas, M.; Robson, K. Focus Groups in Social Research; Sage: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).