Designing a Femtosecond-Resolution Bunch Length Monitor Using Coherent Transition Radiation Images

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Longitudinal Bunch Profile Monitoring

1.2. Scope

2. Materials and Methods

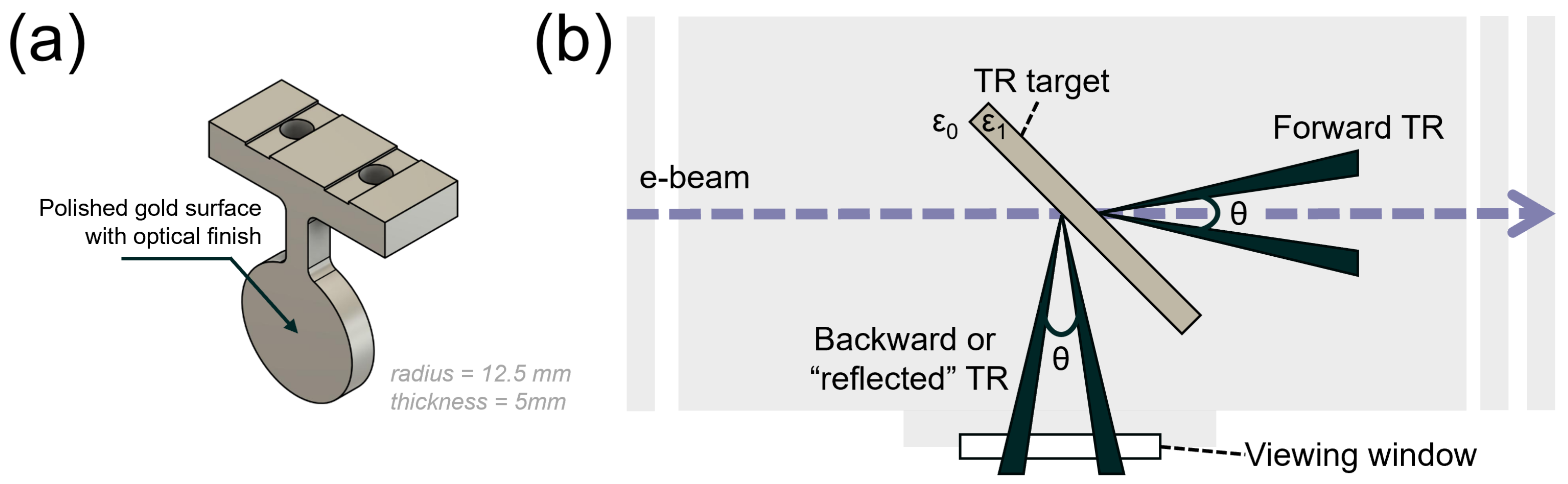

2.1. Generation of Coherent Transition Radiation

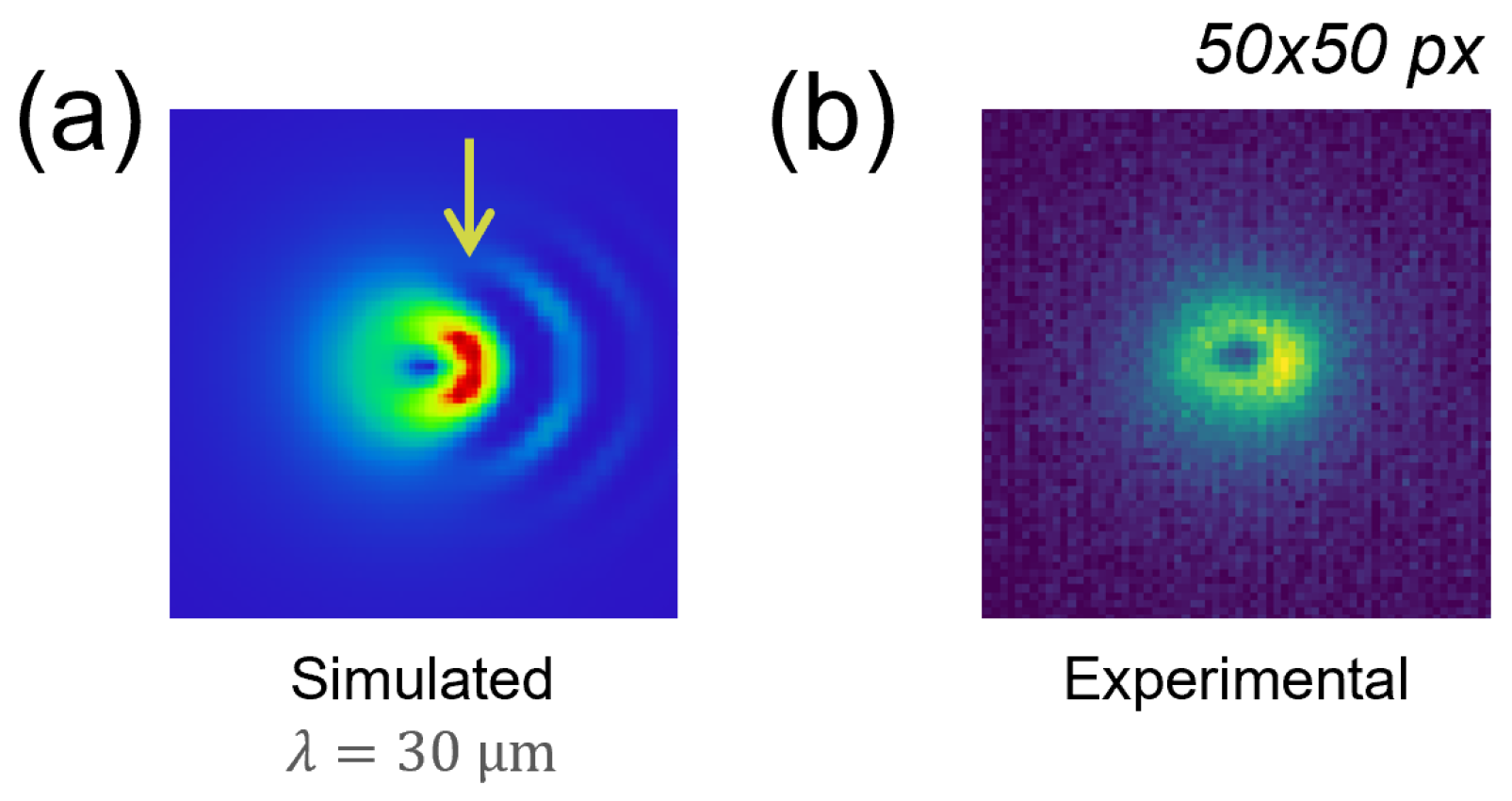

2.2. Study of Coherent Transition Radiation

2.2.1. Spectral Techniques

2.2.2. Scalar Techniques

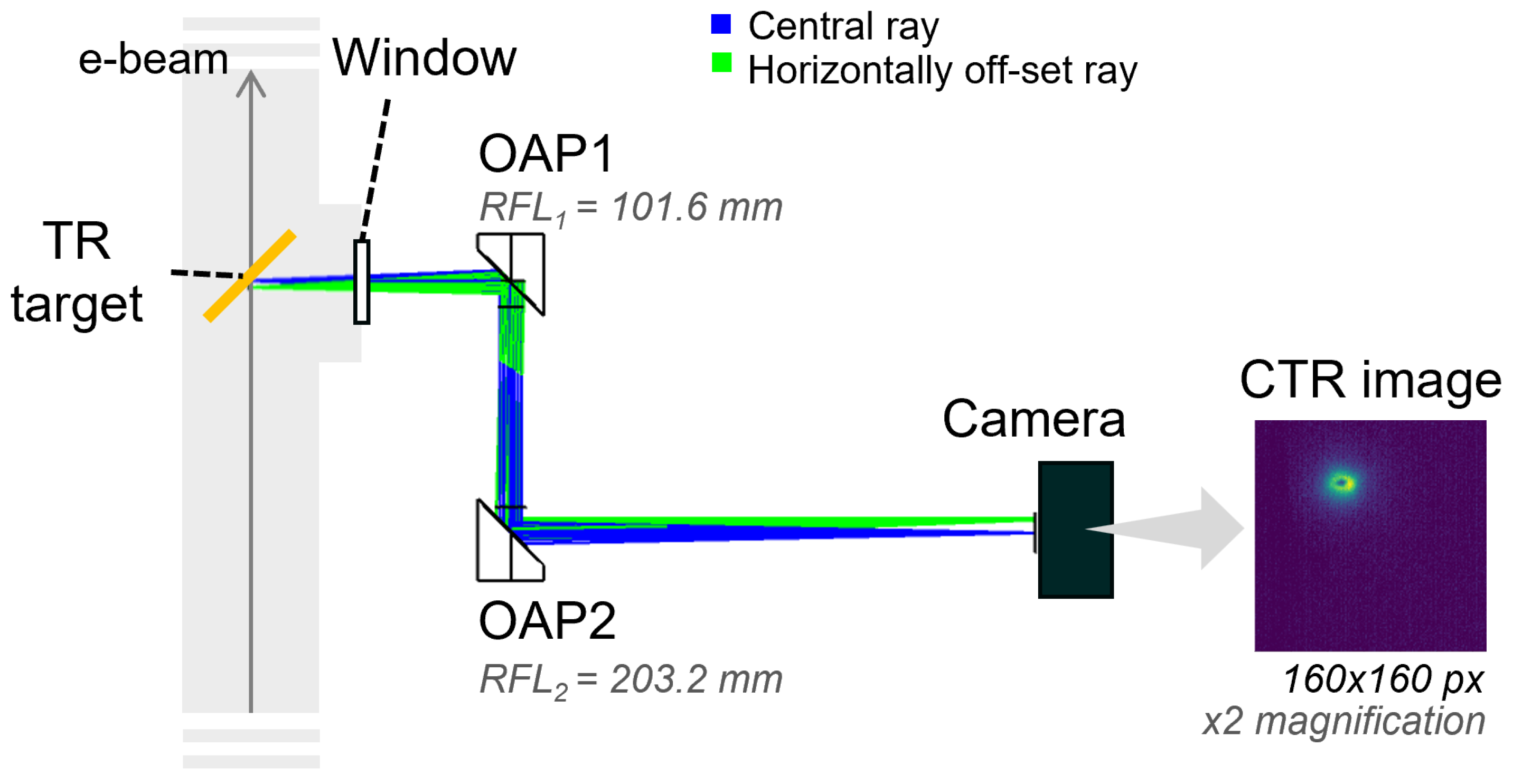

2.3. Device Concept and Design

- The high-resistivity float-zone silicon (HRFZ-Si) window (TYDEX, LLC.: St. Petersburg, Russia) was installed at the vacuum viewport. HRFZ-Si is one of the most commonly used materials in THz optics and is suitable for a wide range of wavelengths, ranging from near-infrared (≥1.2 m) to >1000 mm [35].

- The mm (Ø1″) protected silver-coated OAPs with reflected focal lengths mm (4″) and mm (8″) (Thorlabs Inc.: Newton, NJ, USA), resulting in a magnification [34].

- The pyroelectric broadband array Pyrocam™ IIIHR GigE (Ophir Optronics Solutions Ltd.: Jerusalem, Israel) [39], namely PY-III-HR-C-A-PRO, has a spectral range of 13–355 nm and 1.06–3000 m, an active area of mm, a dynamic range of 60 dB, and a frame rate with a maximum resolution of 100 fps.

3. Results

3.1. Installation

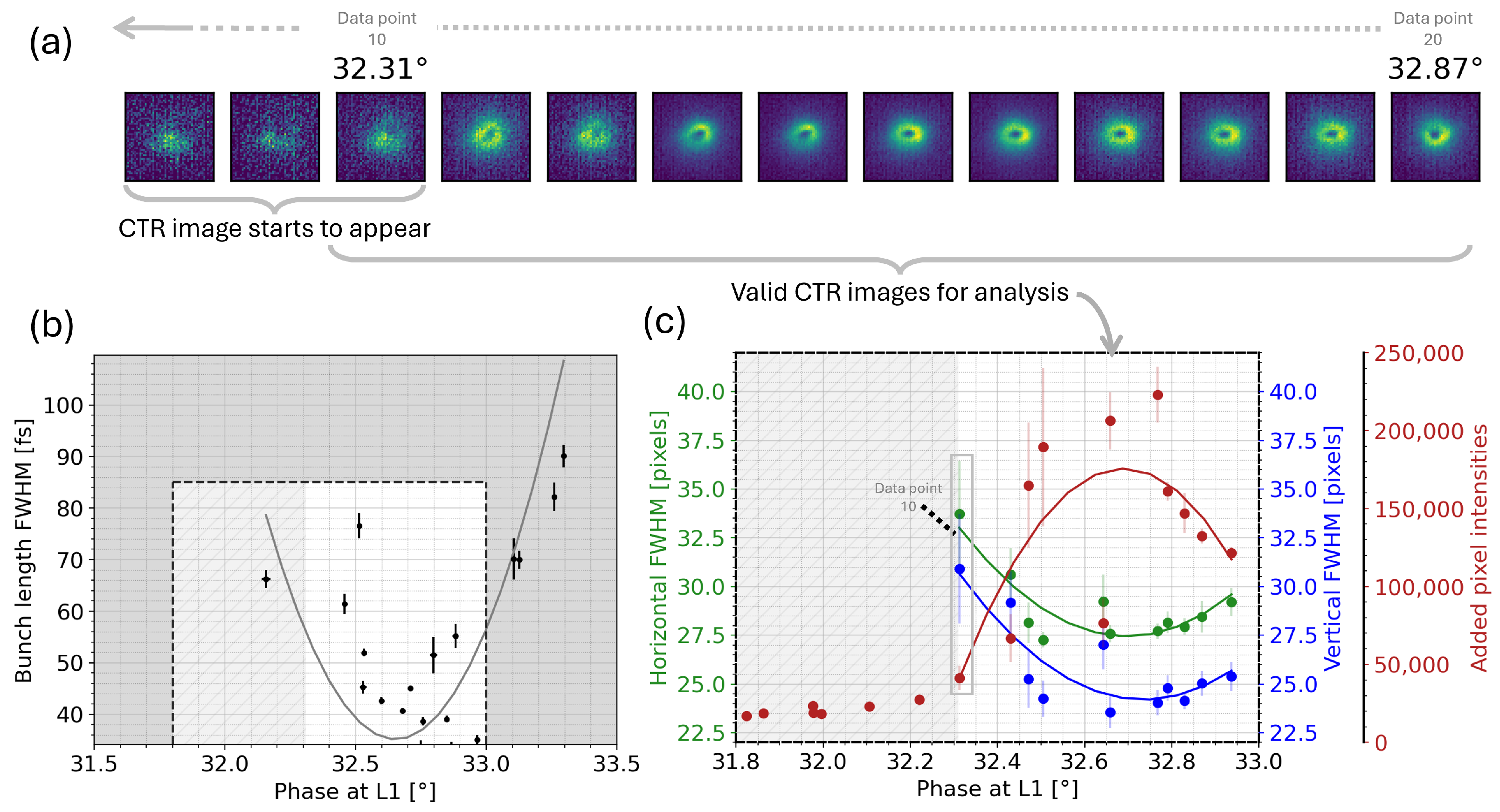

3.2. Data Collection and Preprocessing

3.3. CTR Image Analysis and the Bunch Length

4. Discussion

4.1. Image Acquisition System Improvements

4.2. Image Analysis Improvements

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CLIC | Compact Linear Collider |

| CTR | Coherent transition radiation |

| CXR | Coherent radiation |

| EuPRAXIA | European Plasma Research Accelerator with Excellence in Applications |

| FEL | Free electron laser |

| FWHM | Full width at half maximum |

| HRFZ-Si | High-resistivity float-zone silicon |

| LPS | Longitudinal phase space |

| LWFA | Laser-driven plasma wakefield accelerator |

| MDL | Main drive line |

| OAP | Off-axis parabolic (mirror) |

| PWFA | Beam-driven plasma wakefield accelerator |

| RF | Radiofrequency |

| RFL | Reflected focal length |

| ROI | Region of interest |

| SPF | Short-pulse facility |

| TDC | Transverse deflecting cavity |

| TDS | Transverse deflecting structure |

| TR | Transition radiation |

References

- Muggli, P. Beam-Driven Systems, Plasma Wakefield Acceleration. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.05226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajima, T.; Malka, V. Laser plasma accelerators. Plasma Phys. Control. Fusion 2020, 62, 034004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malka, V. Laser plasma accelerators. Phys. Plasmas 2012, 19, 034004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malka, V. Laser Plasma Accelerators: Towards High Quality Electron Beam. In Laser Pulse Phenomena and Applications; InTech: London, UK, 2010; Volume 25, pp. e275–e281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downer, M.C.; Zgadzaj, R.; Debus, A.; Schramm, U.; Kaluza, M.C. Diagnostics for plasma-based electron accelerators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2018, 90, 35002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, O.; Burrows, P.N.; Calatroni, S.; Lasheras, N.C.; Corsini, R.; D’Auria, G.; Doebert, S.; Faus-Golfe, A.; Grudiev, A.; Latina, A.; et al. The CLIC project. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.09186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, A. Bunch Length Diagnostics: Current Status and Future Directions. In Proceedings of the 2018 CERN-Accelerator-School Course on Beam Instrumentation, Tuusula, Finland, 2–15 June 2018; pp. 305–317. [Google Scholar]

- Prat, E.; Kittel, C.; Calvi, M.; Craievich, P.; Dijkstal, P.; Reiche, S.; Schietinger, T.; Wang, G. Experimental characterization of the optical klystron effect to measure the intrinsic energy spread of high-brightness electron beams. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 2024, 27, 30701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prat, E.; Geng, Z.; Kittel, C.; Malyzhenkov, A.; Marcellini, F.; Reiche, S.; Schietinger, T.; Craievich, P. Attosecond time-resolved measurements of electron and photon beams with a variable polarization X-band radiofrequency deflector at an X-ray free-electron laser. Adv. Photonics 2025, 7, 026002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletti, M.; Assmann, R.; Couprie, M.E.; Ferrario, M.; Giannessi, L.; Irman, A.; Pompili, R.; Wang, W. Prospects for free-electron lasers powered by plasma-wakefield-accelerated beams. Nat. Photonics 2024, 18, 780–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prat, E.; Malyzhenkov, A.; Craievich, P. Sub-femtosecond time-resolved measurements of electron bunches with a C-band radio-frequency deflector in x-ray free-electron lasers. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2023, 94, 043103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxson, J.; Cesar, D.; Calmasini, G.; Ody, A.; Musumeci, P.; Alesini, D. Direct Measurement of Sub-10 fs Relativistic Electron Beams with Ultralow Emittance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 118, 154802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrens, C.; Decker, F.J.; Ding, Y.; Dolgashev, V.A.; Frisch, J.; Huang, Z.; Krejcik, P.; Loos, H.; Lutman, A.; Maxwell, T.J.; et al. Few-femtosecond time-resolved measurements of X-ray free-electron lasers. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijkstal, P.; Qin, W.; Tomin, S. Longitudinal phase space diagnostics with a nonmovable corrugated passive wakefield streaker. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 2024, 27, 050702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarini, O.; Cabadaǧ, J.C.; Chang, Y.Y.; Köhler, A.; Kurz, T.; Schöbel, S.; Seidel, W.; Bussmann, M.; Schramm, U.; Irman, A.; et al. Multioctave high-dynamic range optical spectrometer for single-pulse, longitudinal characterization of ultrashort electron bunches. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 2022, 25, 012801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curcio, A.; Bergamaschi, M.; Corsini, R.; Farabolini, W.; Gamba, D.; Garolfi, L.; Kieffer, R.; Lefevre, T.; Mazzoni, S.; Fedorov, K.; et al. Noninvasive bunch length measurements exploiting Cherenkov diffraction radiation. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 2020, 23, 22802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konoplev, I.V.; Doucas, G.; Harrison, H.; Lancaster, A.J.; Zhang, H. Single shot, nondestructive monitor for longitudinal subpicosecond bunch profile measurements with femtosecond resolution. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 2021, 24, 22801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, B.; Lockmann, N.M.; Schmüser, P.; Wesch, S. Benchmarking coherent radiation spectroscopy as a tool for high-resolution bunch shape reconstruction at free-electron lasers. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 2020, 23, 62801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockmann, N.M.; Gerth, C.; Schmidt, B.; Wesch, S. Noninvasive THz spectroscopy for bunch current profile reconstructions at MHz repetition rates. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 2020, 23, 112801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesch, S.; Schmidt, B.; Behrens, C.; Delsim-Hashemi, H.; Schmüser, P. A multi-channel THz and infrared spectrometer for femtosecond electron bunch diagnostics by single-shot spectroscopy of coherent radiation. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2011, 665, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heigoldt, M.; Popp, A.; Khrennikov, K.; Wenz, J.; Chou, S.W.; Karsch, S.; Bajlekov, S.I.; Hooker, S.M.; Schmidt, B. Temporal evolution of longitudinal bunch profile in a laser wakefield accelerator. Phys. Rev. Spec. Top. Accel. Beams 2015, 18, 121302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajlekov, S.I.; Heigoldt, M.; Popp, A.; Wenz, J.; Khrennikov, K.; Karsch, S.; Hooker, S.M. Longitudinal electron bunch profile reconstruction by performing phase retrieval on coherent transition radiation spectra. Phys. Rev. Spec. Top. Accel. Beams 2013, 16, 040701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfenden, J.; Welsch, C.P.; Pacey, T.H.; Shkvarunets, A. Coherent Transition Radiation Spatial Imaging as a Bunch Length Monitor. In Proceedings of the 10th International Particle Accelerator Conference (IPAC’19), Melbourne, Australia, 19–24 May 2019; pp. 2713–2716. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfenden, J.; Guisao-Betancur, A.; Welsch, C.; Kyle, B.; Pacey, T.; Mansten, E.; Thorin, S.; Brandin, M. First demonstration of coherent radiation imaging for bunch-by-bunch longitudinal compression monitoring. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.04689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assmann, R.W.; Weikum, M.K.; Akhter, T.; Alesini, D.; Alexandrova, A.S.; Anania, M.P.; Andreev, N.E.; Andriyash, I.; Artioli, M.; Aschikhin, A.; et al. EuPRAXIA Conceptual Design Report. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2020, 229, 3675–4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlovets, D.V.; Potylitsyn, A.P. Universal description for different types of polarization radiation. arXiv 2009, arXiv:0908.2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verzilov, V.A. Transition radiation in the pre-wave zone. Phys. Lett. Sect. A Gen. At. Solid State Phys. 2000, 273, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlovets, D.V.; Potylitsyn, A.P. Transition radiation in the pre-wave zone for an oblique incidence of a particle on the flat target. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. Atoms 2008, 266, 3738–3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, T.J.; Behrens, C.; Ding, Y.; Fisher, A.S.; Frisch, J.; Huang, Z.; Loos, H. Coherent-radiation spectroscopy of few-femtosecond electron bunches using a middle-infrared prism spectrometer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 111, 184801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellano, M.; Cianchi, A.; Orlandi, G.; Verzilov, V.A. Effects of diffraction and target finite size on coherent transition radiation spectra in bunch length measurements. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 1999, 435, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorov, K.; Karataev, P.; Saveliev, Y.; Pacey, T.; Oleinik, A.; Kuimova, M.; Potylitsyn, A. Development of longitudinal beam profile monitor based on Coherent Transition Radiation effect for CLARA accelerator. J. Instrum. 2020, 15, C06008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkvarunets, A.G.; Fiorito, R.B. Vector electromagnetic theory of transition and diffraction radiation with application to the measurement of longitudinal bunch size. Phys. Rev. Spec. Top. Accel. Beams 2008, 11, 012801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, C.B.; Esarey, E.; van Tilborg, J.; Leemans, W.P. Theory of coherent transition radiation generated at a plasma-vacuum interface. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Phys. Plasmas Fluids Relat. Interdiscip. Top. 2004, 69, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorlabs Inc. Off-Axis Parabolic Mirrors, Protected Silver Coating. Available online: https://www.thorlabs.com/newgrouppage9.cfm?objectgroup_id=7004 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Rogalin, V.E.; Kaplunov, I.A.; Kropotov, G.I. Optical Materials for the THz Range. Opt. Spectrosc. 2018, 125, 1053–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, S.; Garritano, J.; Bajwa, N.; Nowroozi, B.; Llombart, N.; Grundfest, W.; Taylor, Z.D. THz optical design considerations and optimization for medical imaging applications. Terahertz Emit. Receiv. Appl. V 2014, 9199, 91990S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brückner, C.; Notni, G.; Tünnermann, A. Optimal arrangement of 90° off-axis parabolic mirrors in THz setups. Optik 2010, 121, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, N.; Lloyd-Hughes, J. Optimum Optical Designs for Diffraction-Limited Terahertz Spectroscopy and Imaging Systems Using Off-Axis Parabolic Mirrors. J. Infrared Millim. Terahertz Waves 2023, 44, 981–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ophir Optronics Solutions Ltd. Pyrocam™ IIIHR GigE 160x160 Pyroelectric Array Laser Beam Profiler. Available online: https://www.ophiropt.com/en/f/pyrocam-iiihr-gige-laser-beam-profiler (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- TYDEX, LLC. Silicon. Available online: https://www.tydexoptics.com/materials1/fortransmissionoptics/silicon/ (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Ansys Zemax OpticStudio, version 2023 R2.02; ANSYS, Inc.: Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2023.

- Thorin, S. Characterisation of the MAX IV arc Compressors Using an S-Band Deflector. 2024. Available online: https://indico.psi.ch/event/15973/contributions/50998/ (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Guisao-Betancur, A.; Welsch, C.P.; Wolfenden, J.; Grimm, O.; Mansten, E.; Thorin, S.; Lundquist, J. Single-shot electron bunch profile monitor based on coherent transition radiation imaging. In Proceedings of the 14th International Beam Instrumentation Conference (IBIC’25), Liverpool, UK, 7–11 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guisao-Betancur, A.; Wolfenden, J.; Mansten, E.; Thorin, S.; Lundquist, J.; Grimm, O.; Welsch, C.P. Designing a Femtosecond-Resolution Bunch Length Monitor Using Coherent Transition Radiation Images. Instruments 2025, 9, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/instruments9040029

Guisao-Betancur A, Wolfenden J, Mansten E, Thorin S, Lundquist J, Grimm O, Welsch CP. Designing a Femtosecond-Resolution Bunch Length Monitor Using Coherent Transition Radiation Images. Instruments. 2025; 9(4):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/instruments9040029

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuisao-Betancur, Ana, Joseph Wolfenden, Erik Mansten, Sara Thorin, Johan Lundquist, Oliver Grimm, and Carsten P. Welsch. 2025. "Designing a Femtosecond-Resolution Bunch Length Monitor Using Coherent Transition Radiation Images" Instruments 9, no. 4: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/instruments9040029

APA StyleGuisao-Betancur, A., Wolfenden, J., Mansten, E., Thorin, S., Lundquist, J., Grimm, O., & Welsch, C. P. (2025). Designing a Femtosecond-Resolution Bunch Length Monitor Using Coherent Transition Radiation Images. Instruments, 9(4), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/instruments9040029