Abstract

Despite our traditional concept-based understanding of ferromagnetism, an investigation of this phenomenon has revealed several other facts. Ferromagnetism was previously supposed to be exhibited by only a few elements. Subsequently, it was realized that specific elements with d- or f- orbitals demonstrated this phenomenon. When elements without these orbitals exhibited ferromagnetism, intrinsic origin-based and structural defect-based theories were introduced. At present, nonmagnetic oxides, hexaborides of alkaline-earth metals, carbon structures, and nonmetallic non-oxide compounds are gaining significant attention owing to their potential applications in spintronics, electronics, biomedicine, etc. Therefore, herein, previous work, recent trends, and the applications of these materials and studies based on relevant topics, ranging from the traditional understanding of ferromagnetism to the most recent two-element-based systems, are reviewed.

1. Introduction

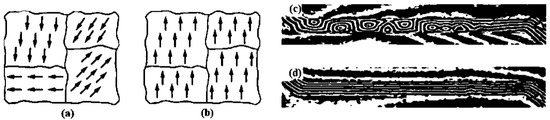

Ferromagnetism is a phenomenon whereby a substance can become a permanent magnet or strongly reacts to a magnetic field. The term “ferromagnetism” is derived from the magnetism detected in Fe2+ or Fe, as Fe was the first element in which ferromagnetism was observed [1]. Unlike nonmagnetic compounds, the compounds exhibiting ferromagnetism show the spontaneous parallel alignment of permanent dipoles due to the movement of electrons around atomic orbitals. Pierre-Ernest Weiss discovered the structural alignments of dipoles [2]. Although these alignments develop high magnetizations even in the absence of a magnetic field, they occur in microscopic spaces known as domains. As these domains do not possess alignments, the ferromagnetic compound does not, by itself, act as a magnet. However, upon exposure to an external magnetic field, these domains align in different directions and maintain themselves in a particular direction, creating a temporary magnetic field within the substance. In the absence of a magnetic field, the net magnetic field is significantly lower, approximately equal to zero. These domains of ferromagnetic elements have been investigated in the absence and presence of a magnetic field (Figure 1a–d).

Figure 1.

Alignments of magnetic domains in the absence and presence of a magnetic field. (a,b): Alignment of the magnetic domain in the absence and presence of a magnetic field (Microsoft Bing), respectively. (c,d): Images of the magnetic domain in the presence and absence of a magnetic field, respectively, acquired by a Lorentz electron microscope [3] (Published with permission of SPIE).

Naturally occurring elements, such as Co, Ni, and Fe, as well as the alloys formed by these elements and some metal and nonmetal oxides that demonstrate ferromagnetism, are termed as “ferromagnetic substances” [4]. The materials and elements exhibiting ferromagnetism can function within a certain temperature threshold known as the Curie temperature. When ferromagnetic substances are heated above the Curie temperature, they lose their ferromagnetic properties and become weakly magnetic, i.e., paramagnetic. This is because, at temperatures above the Curie temperature, the thermal energy is sufficient to break the internal alignments of domains. Below the Curie temperature, magnetism can be permanently induced in these materials. When ferromagnetic materials are subjected to constant external magnetic fields, the abovementioned phenomenon occurs as the magnetic domains are aligned in the same direction (Figure 1b). However, if these materials are exposed to external magnetic fields for prolonged durations, they become permanently magnetized [5]. Naturally occurring load stones are perfect examples of this type of phenomenon. Generally, ferromagnetic substances are subjected to certain degrees of magnetic fields to align their domains in particular directions and induce permanent magnetization. In most of these substances, the induced alignments of the domains were maintained; nevertheless, in some of these substances, the domains were still aligned in previous arrangements. The phenomenon whereby the domains of a ferromagnetic substances under a magnetic field remain in the same configurations as earlier is referred to as “hysteresis” [6].

2. Past Work

Previously, Fe was considered to be the first element to exhibit ferromagnetism; however, later, it was discovered that the elements neighboring Fe in the periodic table, as well as the alloys formed by these elements, Al, and Ti, were also capable of demonstrating ferromagnetism. The ferromagnetism in these materials originated from the presence of empty d orbitals. These materials are substantially influenced by external magnetic fields and exhibit permanent magnetism even in the absence of magnetic fields. Moreover, when these materials are heated for an extended period of time, they lose their ferromagnetic properties. The arrangements of magnetic domains are primarily responsible for the ferromagnetic properties of these materials. The magnetic domains of these materials normally cancel each other out, leading to zero magnetism; nevertheless, under external magnetic fields, these domains align themselves in a particular manner. Traditionally, ferromagnetic materials have been classified as magnetized and unmagnetized. Magnetized ferromagnetic materials exhibit ferromagnetism even in the absence of an external magnetic fields, whereas unmagnetized ferromagnetic materials exhibit almost null magnetism without external magnetic fields [1]. Initially, the ferromagnetic properties of Fe, Co, Ni, permalloy, awaruite, chromium dioxide, wairakite, and magnate were investigated. These materials are still in use because they are inexpensive, lose very little hysteresis, offer less resistance, can easily be used up to 30 °C, and are highly stable [7].

3. Recent Trends

Conventionally used ferromagnetic materials exhibit some limitations, such as a low hardness, which hinders their application and has necessitated the development of better ferromagnetic materials [8]. When ferromagnetism was unexpectedly observed in Ge, Mn, and Te, several studies were conducted on inorganic nonmetallic materials, and many ferromagnetic materials were successfully discovered. Traditionally, ferromagnetism was believed to be demonstrated by elements with partially filled d or f orbitals. In contrast, when researchers revealed that an element without partially filled d or f orbitals could also exhibit ferromagnetism, it opened up a completely new realm in the field of ferromagnetism. Reducing one of the dimensions limits the electronic transition, promoting column interactions and increasing the bandwidth ratio. This increase in material–column interactions and bandwidth ratio induces magnetism in these materials [9]. Numerous materials with either partially filled f or d orbitals were both theoretically and experimentally analyzed. Nonmagnetic elements that show ferromagnetism in their oxide compounds or other forms are referred to as d0 ferromagnetic substances, and the corresponding ferromagnetism is termed d0 ferromagnetism. d0 Ferromagnetism was discovered for the first time in HfO2 when the O-rich surface of Hf with no magnetic ions in HfO2 exhibited ferromagnetism [10]. Thereafter, the ferromagnetic properties of oxides of other elements of the same period, including ZnO, Cu2O, and TiO2, were examined, and these oxides were found to demonstrate ferromagnetism; furthermore, numerous other nonmagnetic d-block elements, such as Sc, Cr, Mn, Zr, and Nb, were reported to exhibit ferromagnetism upon doping with some specific type of impurities [11]. Similarly, oxides of f block elements, such as CeO2 doped with Co and Mn, were investigated to further explore this [12]. Moreover, the oxides of nonmagnetic elements without d or f orbitals, including Al2O3, In2O3, and CaO, demonstrated ferromagnetic properties, implying that these properties can be modified within elements [13]. Subsequently, the non-oxide nonmagnetic compound BN, C structures, and rock salts were also reported to possess considerable ferromagnetism [14]. Accordingly, it was concluded that modification of the internal environment of a nonmagnetic element or a ferromagnetic nonmetal by defects, such as valency complexes, vacancies, and impurities, arising from the integration of the element with another element, can induce magnetic properties [15]. Thus, the phenomenon of ferromagnetism is universal, and is demonstrated not only by magnetic elements, but also their impurities and non-magnetic elements by doping with oxide or other inorganic elements [16]. Furthermore, the drawbacks that limit the use of traditional magnetic elements have been overcome by mixing these elements with other compounds; for example, B [8]. Many modern medical procedures, such as varicose treatment, hyperthermia, and endovenous thermal ablation require local heating of the human body. However, it is challenging to convert electrical power into heat flux and directly transfer this heat flux to the required area without harming the surrounding tissue. Heating catheters composed of biocompatible magnetic composites with low-frequency induction heating (LFIH) is an effective solution in this regard [17]. Cu–Mn–Ga-based ferromagnetic shape memory single crystals were fabricated for the first time by annealing their cast polycrystalline alloys. Their functional properties have also been reported. The obtained results should be highly significant for the development of brittle ferromagnetic Cu–Mn–Ga alloys [18]. Numerous studies have been performed on the advancement of ferromagnetism, which have resulted in the discovery of numerous ferromagnetic compounds.

3.1. Hexaborides of Alkaline-Earth Metals

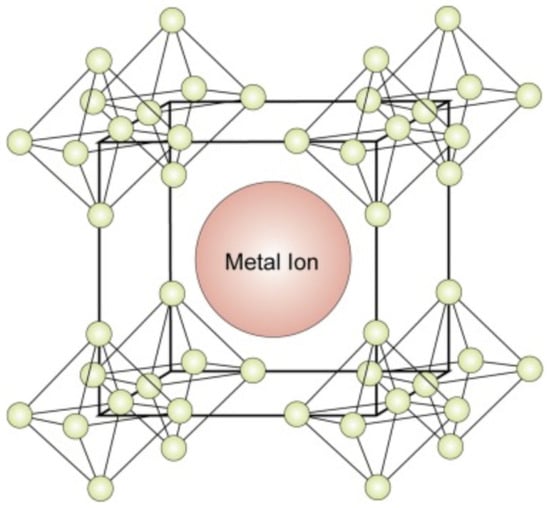

Boride compounds are gaining considerable attention because of their mechanical properties and high conductivities. They are widely used to overcome the hardness limitations of magnetic elements [8]. B, as an electron-deficient element, facilitates the trapping of electrons from other metal species by forming a strong B bond with these species. They produce either divalent-metal hexaborides or divalent hexaborides with alkaline-earth metals [19]. The hexaborides of alkaline-earth metals, including SrB6, BaB6, and CaB6, are extremely sensitive to stoichiometry because of their high impurity contents and inferior physical properties. When these compounds were doped with Th and La, the resulting compounds demonstrated weak ferromagnetism at high temperatures [20]. Although these compounds lack d or f orbitals, their ferromagnetism has attracted significant research attention [11]. Divalent hexaborides (MB6, M = Sr, Ba, Ca) crystallize in CsCl-type cubic structures, and their physical properties are substantially similar to those of Group IIA elements, that is, alkaline-earth metals [21]. The structure of a divalent hexaboride comprises a central metal ion surrounded by hexaboride ions (Figure 2). In the CaB6 prototype structure, a single metal atom is surrounded by eight octahedra of B atoms, each centered on the corner of the cube. There are five B atoms in an octahedron, with four adjacent atoms and one along one of its axes. Moreover, 24 B atoms are coordinated at the center of the atom; nevertheless, no valence bonds are formed between them [22]. In contrast, the B atoms are covalently bonded to each other and are responsible for several physical and chemical properties of these compounds [23]. A cubic B sublattice is inherently electron-deficient because the B atoms must distribute their three valence electrons over five bonds. This implies that a sublattice cannot exist, even with the donation of electrons from the metals. Hexaborides must contain a metal cation with a charge of at least +2 to be electronically stable [24]. KB6 with a low K content has been synthesized in controlled environments [25]. Consequently, considering that the B sublattice forms a semi-rigid “cage,” alkaline-earth, rare-earth, and some actinide cations are the only candidates in this regard based on their sizes and valences.

Figure 2.

Crystal structure of the hexaborides of alkaline-earth metals [26].

3.1.1. CaB6

CaB6 was the first compound to exhibit ferromagnetism upon being lightly doped with La. Ferromagnetism exists on and around the La-doped CaB6 surface, and the origin of this weak ferromagnetism is extrinsic [27]. CaB6 is a band insulator with a band gap of 0.2 eV. However, due to the formation of impurities because of B vacancies at the CaB6 sublattice, CaB6 demonstrates a magnetic moment and undergoes exchange splitting [28]. CaB6 is doped with transition metals to enhance its ferromagnetism. After doping, the ferromagnetism still originates from the B vacancies and magnetic moments generated by the polarization of conducting electrons in the transition metal. CaB6 exhibits ferromagnetism in the crystal and thin-film forms [11].

3.1.2. BaB6

Typically, BaB6 thin films exhibit weak magnetism in the temperature range from 723 to 873 K. The virtual temperature independence of these films was exhibited down to 4 K, and isotropic and anhysteretic magnetizations were observed in these films. Due to interferences, defects, and grain boundaries, magnetization was detected in fewer than 4.5% of the total volume fraction of BaB6 thin films [29]. Nevertheless, the magnetic characteristics of BaB6 thin films improved when they were doped with a lanthanum hexabromide system. Owing to the difference between the ionic radii of Ba and La, the resulting system demonstrated ferromagnetism even at room temperature [30].

3.1.3. SrB6

A weak ferromagnetism has been observed in SrB6. SrB6 is a semiconductor with a sizable energy gap of approximately 1 eV at the X-point in the Brillouin zone, as observed via angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy [21]. Analysis of a single crystal of SrB6 at low temperatures indicated 0.001 electrons per Sr atom. These data provide evidence that the electron–hole Coulomb effect is probably responsible for the weak ferromagnetism of SrB6 [31]. Recently, the ordered defect of SrB6 has been found to be responsible for intrinsic ferromagnetism. Although the maximum magnetic susceptibility of SrB6 is achieved at 1 K, it does not considerably affect the weak ferromagnetism of SrB6 [32].

3.2. Nonmagnetic Oxides

Numerous studies have been conducted on nonmagnetic oxides, and several other oxides of nonmetallic elements demonstrating ferromagnetism at room temperature have been discovered; nevertheless, there remains a knowledge gap regarding the origin of ferromagnetism in these compounds. Impurities and surface defects are the topic of controversies that are often discussed whenever the discussion arises [33]. Ferromagnetism has been discovered in different oxides, for example, Mg, Zn, Ce, Hf, Ti, Sr, Sn, and Zr oxides, disproving the traditional concept of the requirement of d or f orbitals to exhibit ferromagnetism. Among them, oxides of Zn, Mg, Hf, and Ce are widely used and have extensive applications, whereas the remaining oxides exhibit weak ferromagnetism in the free state or after doping [19].

3.2.1. HfO2

The thin films of Hf and O, both being inorganic and nonmetallic, exhibit ferromagnetism without necessitating dopants. The ferromagnetism of HfO2 has been extensively analyzed and has facilitated research on other oxides and nonmetallic compounds demonstrating ferromagnetism. Previously, the ferromagnetism in HfO2 was attributed to the vacancies in O atoms; later, it was realized that the intrinsic defects originating from the morphology are crucial in the exhibition of ferromagnetism.

However, in the X-ray photoelectron spectrum, O vacancy peaks were detected at higher positions than the O peaks due to intrinsic defects. Results have also shown the involvement of Hf in the bonding structures in ferromagnetism. Polarization occurs in O atoms because of the existence of Hf4+; one of the O atoms can occupy Hf4+, leading to Hf3+ and e−, generating deep and shallow traps. The e− occupies the Hf3+ orbital, which results in ferromagnetism [34]. Nevertheless, recent studies have demonstrated that neither the non-stoichiometric surfaces of Hf nor low stoichiometries are responsible for the magnetic properties of nonmetallic oxides; instead, non-stoichiometric surfaces with O atoms are responsible for ferromagnetism in nonmetallic oxides [35].

3.2.2. ZnO

Owing to its potential application in spintronic devices, ZnO has attracted research attention. Additionally, it is inexpensive and possesses a wide range of applications [36]. Several ZnO systems have been developed, such as nanowires, capped structures, doped thin films, and single crystals [19]. Studies have revealed that ferromagnetism can be induced in the oxides of nonmagnetic materials, for example, ZnO [37]. Earlier, it was believed that the ferromagnetism in ZnO was induced by carriers and could be modified by changing the carrier density [38]. Furthermore, studies have revealed that the ferromagnetism in ZnO occurs because of O vacancies. There have also been studies related to doping-induced ferromagnetism; however, Zn was able to demonstrate ferromagnetism under both mild doping and in the undoped state, due to its surface defects [39]. Doping increased the ferromagnetism of ZnO [40]. The ferromagnetism exhibited by ZnO at room temperature is O vacancy-dependent [41] and can be controlled by adjusting the particle size [42].

3.2.3. CeO2

Due to its ability to retain and release O vacancies, CeO2 has been employed for power generation due to its environmentally beneficial applications [43]. A change in the concentration of O vacancies can easily promote magnetism in CeO2 [44]. In preliminary studies, CeO2 nanoparticles were found to exhibit ferromagnetism, whereas the bulk material did not demonstrate ferromagnetism. Consequently, it was believed that all metal oxides exhibited ferromagnetism [45], and only CeO2 nanoparticles with sizes smaller than 20 nm could demonstrate ferromagnetism [46]. However, later, it was theoretically and experimentally revealed that the ferromagnetism in CeO2 is induced by structural defects in Ce and O vacancies [47]. Nevertheless, when CeO2 thin films were examined at high temperatures, the ferromagnetism of CeO2 was discovered to be more dependent on O vacancies than on the structural defects in Ce.

3.2.4. MgO

Ferromagnetism in MgO is quite interesting as MgO also lacks free electrons. Intrinsic or dopant-generated defects and vacancies are regarded to be responsible for the room-temperature ferromagnetism of MgO [48]. Primarily, it was assumed that the ferromagnetism of MgO was related to cation vacancies; however, subsequently, ferromagnetism was reported to be correlated with the crystallinity of MgO [49]. Detailed studies based on injection-printed MgO demonstrated that the ferromagnetism in MgO resulted from vacancies in Mg; nevertheless, by increasing the pH of the ink, the number of voids could be increased [50]. However, upon investigating nanosized MgO, it was discovered that, in addition to Mg vacancies, factors such as the degree of crystallinity and calcination temperature-induced changes in phase composition were equally important for the room-temperature ferromagnetism of MgO [51].

3.2.5. TiO2

The ferromagnetic behaviors of rutile and anatase TiO2 were investigated; the magnetism of the rutile TiO2 sample was found to be dependent on O vacancies, whereas that of the anatase sample was discovered to be independent of the sample, as in useful samples. However, both samples were ferromagnetic at room temperature. The ferromagnetism of the rutile sample was larger than that of the anatase sample [52]. When Ga- and oxygen-vacancy-doping in TiO2 were investigated, it was discovered that TiO2 displayed an increase in magnetization with antiferromagnetic and ferromagnetic coupling; however, antiferromagnetic coupling was absent in Ga-doped systems [53]. Co-doped TiO2 also demonstrates weak ferromagnetism, supporting the fact that the ferromagnetism of TiO2 is related to O vacancies [54]. A study of transition metal-doped TiO2 has revealed that ferromagnetism may be slightly enhanced by doping, which may be useful in dilute magnetic semiconductors [55].

3.2.6. ZrO2

Although Zr is a nonmagnetic and non-reducible element [56], similar to most nonmagnetic oxides, the ferromagnetism in ZrO2 is believed to arise from O vacancies [57].

Recent theoretical explanations have also verified that the ferromagnetism in ZrO2 originates from the trapping of electrons by O vacancies. These sites, upon exceeding electron counts, obtain offering and high spinning at their ground state, resulting in ferromagnetism [56]. Nevertheless, several studies have shown that the ferromagnetism of ZrO2 thin films increases upon doping these films with different transition metals. This ferromagnetism is caused by intrinsic defects rather than exchange interactions [58].

3.2.7. SnO2

The ferromagnetism in SnO2 thin films originates from the monovalent O vacancies inside these films, whereas the ferromagnetism in SnO2 arises from surface defects. In SnO2 thin films, an increase in the temperature to 400 °C causes a stronger magnetic effect due to an increase in surface imperfections [59]. Previously, it was discovered that the ferromagnetism of doped SnO2 thin films increased with an increase in temperature [60]. However, later, it was found that when SnO2 thin films were lightly doped with metals, their ferromagnetism was enhanced; in contrast, when these films were heavily doped with metals, their ferromagnetism was destroyed.

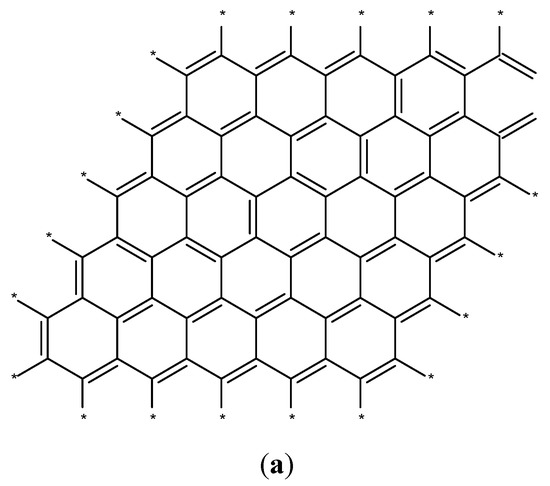

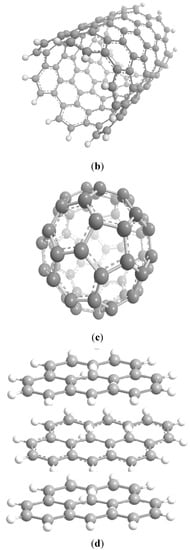

3.3. C Nanostructures

Ferromagnetically active C systems have emerged as one of the most popular research topics in the field of ferromagnetism owing to their various advantages including low weight, high stability, low-cost production, and simple processing. Recent years have witnessed significant advancements using graphene (Figure 3a), C nanotubes (Figure 3b), fullerenes (Figure 3c), and graphite (Figure 3d) [61]. As classic ferromagnetic substances lack d and f orbitals, ferromagnetism in C nanostructures originates from s and p electrons. These nanostructures demonstrate ferromagnetism at low temperatures, and the magnetism is due to the impurities present in these nanostructures [62].

Figure 3.

Schematics of the structures of graphene (a), C nanotubes (b), fullerenes (c), and graphite (d) [61].

3.3.1. C Nanotubes

Recently, the use of C nanotubes has progressively increased due to their unique properties and applications [63]. The magnetism exhibited by C nanotubes has the potential to considerably extend their application range. When these structures come into contact with ferromagnetic materials, a spin-polarized charge is transferred from ferromagnetic materials to these structures [64]. C nanotubes demonstrate ferromagnetism at room temperature. According to research findings, H2 absorption causes ferromagnetism in C nanotubes. However, contrary to this finding, the thickness of the nanotube wall and temperature are the factors responsible for ferromagnetism in C nanotubes [65]. Plasma treatment successfully enhanced the ferromagnetism of this system [66]. At room temperature, a system of single-walled nanotubes easily demonstrated ferromagnetism because of impurities rather than vacancies in C atoms [67].

3.3.2. Fullerenes

C60 was discovered in 1985. Initially, fullerenes were believed to be diamagnetic [68]. Nevertheless, many fullerene-based systems have exhibited ferromagnetism [69]. Ferromagnetism was observed in this system for the first time when C60 was ultrasonically dispersed in a dimethylformamide solution of polyvinylidene fluoride [70]. Ferromagnetism was noticed in an almost structure-destroying state [71], implying that the ferromagnetic behaviors of fullerenes depend on the preparation conditions, such as the time, pressure, and temperature of these systems [72]. This indicates that the ferromagnetism in fullerenes is caused by molecular defects. The pressure and temperature dependencies of these systems were validated by analyzing rhombohedral C60, which showed ferromagnetism to varying degrees [73]. Similarly, the bilayer structure of Pd-doped C60 demonstrated ferromagnetic behavior that was induced by the stacked bilayers of Pd and fullerenes [74].

3.3.3. Graphene

In addition to the several properties of graphene, structural defects may lead to ferromagnetism [75]. Moreover, magic-angle graphene exhibits ferromagnetism in the insulator phase [76]. Upon investigating graphene nanoflakes, it was discovered that they have zigzag edges, which may contribute to their ferromagnetism [77]. The bulk of graphene obtained from functionalized graphene sheets demonstrates ferromagnetism. Graphene also exhibits ferromagnetism due to structural defects [62]. The ferromagnetism of this system was enhanced when graphene was converted to graphene nanoribbons [78]. Similarly, twisted bilayer graphene possesses a conduction band that causes ferromagnetism in its system. By stabilizing the ferromagnetism of this system, it can be used in spintronics, electronics, separation technology, medicine, and other fields.

3.3.4. Graphite

Ferromagnetism in graphite systems is mainly induced by lattice defects. Under irradiation, the magnetic moment of graphite is affected by the adsorption of H2 and irradiated vacancies, whereas the ferromagnetism in the pure bulk material is primarily caused by the topographic defects of the material [79]. A further advantage of ion implantation in graphite is the enhancement of its ferromagnetic properties. In the ion-doped system, ferromagnetism was initially interpreted to be induced by vacancy defects [80]. However, recent studies on graphite systems have revealed that, in addition to intrinsic surface defects, “comet-like” defects with higher magnetic signals are responsible for ferromagnetism in graphite [81]. A magnetization of approximately 2.5 memu/g was noticed for graphite with the highest Curie temperature of approximately 900 K. This suggests that the magnetite cluster c is not responsible for magnetization in this system. It appears that some samples with impurities possess superparamagnetic characteristics instead of ferromagnetism based on their magnetic susceptibilities. Furthermore, ferromagnetism can be enhanced by a strong topological disorder as it suppresses the antiferromagnetic order [63]. Similarly, by controlling the density of induced defects in the system, the magnetization of C in its different systems can be tuned [80].

3.4. Magnetic Boride Compounds

B has the potential to form a wide range of compounds with different electrochemical, magnetic, and stoichiometric properties. Magnetic elements are traditionally used for several applications; nevertheless, they exhibit some limitations such as a low hardness, which must be overcome using elements including B. The hardness of some elements, such as Fe, has been considerably increased by treatment with B [8]. Recent studies on B transition metal compounds have revealed improved mechanical properties for these compounds [82]. Due to the presence of unpaired d or f orbitals, magnetic properties such as high coercivity, high magnetization saturation, etc., can be greatly induced in magnetic boron compounds [83]. A superior magnetism is observed in metallic elements when they are incorporated with borides [84].

Metallic boride compounds including FeB, NiB, and Co3B are intermediates between soft and hard magnets. Although they are magnetically hard, they possess low moments; hence, they are considered semi-hard compounds with immense application possibilities in various fields, for example, data storage and biomedicine [85]. However, very few studies have reported on the development of these compounds as compared to those for other classes of compounds.

3.5. Nonmetallic Non-Oxide System

Nonmetallic non-oxides, such as nitrides, are attracting interest for the induction of magnetization using various elements, similar to the cases of oxides. The magnetism in these compounds is caused by significant spin-exchange interactions in the ionic states. Nevertheless, it is highly useful to stabilize the hole carrier density for doping interactions. Localized acceptors can be utilized to stabilize the quantum confinement effect [86].

These classes of ferromagnetic compounds are specifically prepared from Group 3 and Group 5 elements, and the thicknesses of GaAs, GaN, InAs, and GaP are inversely proportional to their magnetic saturations; furthermore, these compounds can be fabricated using Group 4 elements such as Ge (for example, Mn2+-doped Ge). In Group 4 element-based ferromagnetic compounds, ferromagnetism originates from Mn-induced charge carriers, that is, holes in the material matrix. Bound magnetic polarons (BMPs) are formed during exchange interaction between the magnetic dopant and localized holes. These BMPs are composed of magnetic ions and a localized hole, and the interaction of these BMPs in the presence of a high concentration of dopants leads to ferromagnetism [87]. However, at low temperatures, these BMPs overlap each other and interact with nearby dopants. Eventually, the alignment of these BMPs causes a ferromagnetic transition. Nevertheless, the resulting ferromagnetism is comparatively lesser than those of similar systems. Comparative studies of the saturation magnetizations, observations, and origins of ferromagnetism of different ferromagnetic materials are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative studies of the saturation magnetizations, observations, and origins of ferromagnetism of different ferromagnetic materials.

Additionally, several systems based on three-element doping and the introduction of defects have been developed or are still being developed. However, this review primarily focuses on two element-based systems.

4. Applications

In addition to traditional applications, such as in temporary magnets, generators, magnet production, telephones, tape recorders, and other electric and magnetic devices, ferromagnetic materials can be applied in different fields. These materials are particularly utilized to fabricate devices, including spintronic devices, biomedical devices, electric equipment, sensors, artificial intelligence devices, and neural networks for artificial intelligence, offering both magnetic and electrical properties. The applications of these ferromagnetic materials in some major fields are discussed hereinafter. Although these materials still have considerable potential for further use, most of them have not yet been developed on a commercial scale. Some of the major applications are as follows.

4.1. Spintronic Devices

Spintronics is one of the major application sectors of ferromagnetic materials as these materials can very easily control the injection of spin-polarized carriers [105]. Using this feature, a wide range of data can be transferred and stored. The ultimate goal of this application is to replace complementary metal-oxide semiconductors, that is, transistors, with ferromagnetic materials that consume very little power compared to transistors [106]. In these devices, the information circuits are regulated by either the spin of an electron or the electrical charge in the system [105]. Controlled ferromagnetic material systems enable us to store data with a faster processing of information in their nonvolatile memories, in turn enabling substantially lower power consumption. Ferromagnetic materials possess all the properties that facilitate quantum computing [107]. Ferromagnetic materials can also be used to construct spin logic gates and spin field electron transistors [106]. However, the production of these devices on a commercial scale is still challenging because of various factors such as “manipulation and control,” transport, and efficient injection [105].

4.2. Electronic Devices

Ferromagnetic materials have significant applications in the field of electronics. They can be used to create temporary magnets with extensive applications in electronics. In recent years, different devices, including hard drives, loudspeakers, electromagnets, magnetic tape recorders, transformers, electric motors, and telephones, have been constructed using ferromagnetic materials. At present, these materials are employed to develop advanced devices such as three-dimensional printers, high-performance computers, soft robots, and soft and flexible electronic devices [67]. Similarly, these materials have recently been used in integrated electronic technologies for advanced electrophysiological recording applications [108], thereby facilitating the long-term recording of skin-perceived electrophysiological signals [109].

4.3. Biomedicine

Since the discovery of biomagnetic fields in living organisms, researchers have been using ferromagnetic materials to design and prepare pharmaceuticals that can be successfully and efficiently used. Various medications, including extended-release tablets, enteric-coated tablets, modified drug releasing systems, and multiarticulate delivery systems, have been developed. The healthcare system has significantly improved because of these innovations in drug delivery systems [110]. In addition to the application of ferromagnetic materials in effective drug delivery systems, their use as biosensors and diagnostic agents has promoted their application in the medical field. These materials have also been employed for the successful treatment of cancer using gene therapy [111]. Moreover, several diseases, such as arthritis, diabetes, and any other related diseases that are caused by defects in the gene, can potentially be treated using ferromagnetic materials.

4.4. Artificial Neural Networking

Artificial neural networking is another considerable application of ferromagnetic materials. Ferromagnetic materials have been successfully utilized in the solution to problems such as vibration suppression and superplastic forming modeling wood veneer inspection, which are associated with the optimization of artificial neural networks [112]. It has been reported that the ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic bilayer system can perform switching in magnetization and storage of data in the nonvolatile manurable artificial synapse and can be used for various functions in artificial intelligence [113]. High-performance and low-power-consuming hardware with adaptive neural networking for artificial intelligence can be constructed using ferromagnetic/antiferromagnetic materials [114].

5. Limitations

The theoretical origins of ferromagnetism in many of these materials are still controversial. At present, different techniques, such as impurity band exchange due to the donor, charge transfer, and BMPs, are used to explain the behaviors of ferromagnetic materials [37].

Similarly, the system used to investigate their properties, such as thin films, bulk nanoparticles, the existence of surface defects, and parent element magnetic properties, have a significant impact on repeatability and impurity contamination [13]. The saturation magnetization of ZnO considerably varies (Table 1), and the differences between the saturation magnetizations of different morphological states and different parent materials can easily be determined from the data presented in Table 1. Furthermore, room-temperature magnetic ordering is not possible in the band gaps, which strongly opposes the currently existing interpretation [115] and can be attributed to 3D aggregation, surface contamination, or absence of precipitation. The devices that are used to estimate the different magnetic properties of materials do not exhibit nonmagnetic properties. It has been realized that these devices provide false readings when they come into contact with airborne particles [116].

Under a variable magnetic field, the magnetic flux also deviates owing to misidentification of the magnetic state of the sample and accidental contamination of the system surface. Material contamination is caused by improper handling and cleaning of the material, molting of the material, high-temperature annealing and processing of the sample substrate, and accidental contamination [9]. This contamination makes the reproducibility and analysis of material data difficult because of the formation of a segregated system and different magnetic characteristics of the material during each processing stage [117].

6. Conclusions

Based on the aforementioned past and present trends, it can be concluded that the materials used in the past are still dominantly used; however, some improvements are still required. Some traditionally used materials, including the system of metal borides, can be advanced. Recently, significant advances have been made in the field of ferromagnetism. Existing systems have substantial potential for use in various applications. Nevertheless, there is still a knowledge gap that needs to be filled in due course. Similarly, in materials that exhibit d0 ferromagnetism, instead of developing more materials, a reproducible procedure to formulate the product needs to be discovered so that these materials can be used up during their application. According to recent research, ferromagnetism can be induced in some materials via the application of an electric current or voltage. Ferromagnetism has been induced in LaMnO3 and SrCoO, which are antiferromagnetic. Recently, ferromagnetism was induced in diamagnetic Fe pyrite (“fool’s gold”) via the application of voltage [118]. Overall, although ferromagnetic materials have been significantly developed, commercialization of these materials is considerably more time-consuming than their development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B., N.K.S. and P.R.; software, A.B. and N.K.S.; validation, A.B., N.K.S. and P.R.; resources, A.B.; data curation, N.K.S.; writing-original draft preparation, P.R.; writing-review and editing, A.B., N.K.S. and P.R.; visualization, P.R; supervision, A.B. and N.K.S.; project administration, A.B.; funding acquisition, A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by TWAS, ITALY from the 17-533RG/CHE/AS_G/TWAS Research Grants.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

A.B. acknowledges Editage Cactus Communications Pvt. Ltd. Mumbai, India for editing support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chikazumi, S.; Graham, C.D. Physics of Ferromagnetism 2e (No. 94); Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cullity, B.D.; Graham, C.D. Introduction to Magnetic Materials, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, L.-C.; Zhang, Y.; Zuo, S.-L.; He, M.; Cai, J.-W.; Wang, S.-G.; Wei, H.-X.; Li, J.-Q.; Zhao, T.-Y.; Shen, B.-G. Lorentz transmission electron microscopy studies on topological magnetic domains. Chin. Phys. B 2018, 27, 066802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, A. Handbook of Modern Ferromagnetic Materials; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hashmi, S. Comprehensive Materials Processing; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Effen, M.; Quintela, D.H.; Jordan, R.; Westhoff, W.; Moreno, W. Wireless sensor networks for flash-flood alerting. In Proceedings of the Fifth IEEE International Caracas Conference on Devices, Circuits and Systems, 2004, Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, 3–5 November 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharoni, A. Introduction to the Theory of Ferromagnetism (Vol. 109); Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Li, L.; Bao, K.; Zhu, P.; Tao, Q.; Ma, S.; Liu, B.; Ge, Y.; Li, D.; Cui, T. Synthesis and characterization of a strong ferromagnetic and high hardness intermetallic compound Fe2B. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 27425–27432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R. Unexpected magnetism in nanomaterials. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2013, 346, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das Pemmaraju, C.; Sanvito, S. Ferromagnetism Driven by Intrinsic Point Defects inHfO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 217205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanta, S.K.; Mishra, S.N. Electronic structure and magnetic moment of dilute transition metal impurities in semi-metallic CaB6. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2017, 444, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaresan, A.; Bhargavi, R.; Rangarajan, N.; Siddesh, U.; Rao, C.N.R. Ferromagnetism as a universal feature of nanoparticles of the otherwise nonmagnetic oxides. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 74, 161306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coey, J.M.D. Magnetism in d0 oxides. Nat. Mater. 2019, 18, 652–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gao, D.; Si, M.; Zhu, Z.; Yang, G.; Shi, Z.; Xue, D. Origin of the unexpected room temperature ferromagnetism: Formation of artificial defects on the surface in NaCl particles. J. Mater. Chem. C 2013, 1, 6216–6222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, T.L. Nanomagnetism in otherwise nonmagnetic materials. arXiv 2009, arXiv:0904.1550. [Google Scholar]

- Sundaresan, A.; Rao, C.N.R. Ferromagnetism as a universal feature of inorganic nanoparticles. Nano Today 2009, 4, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Le, M.Q.; Cottinet, P.-J.; Griffiths, P.; Baeza, G.P.; Capsal, J.-F.; Lermusiaux, P.; Della Schiava, N.; Ducharne, B. Development of anisotropic ferromagnetic composites for low-frequency induction heating technology in medical applications. Mater. Today Chem. 2021, 19, 100395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, M.; Qing, X.; Guo, L.; Hong, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, C.; Liu, X. Development of Cu-Mn-Ga-based ferromagnetic shape memory single crystals. Materialia 2020, 12, 100789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungu, I.I.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Fleaca, C. Unexpected Ferromagnetism—A Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.P.; Hall, D.; Torelli, M.E.; Fisk, Z.; Sarrao, J.L.; Thompson, J.D.; Ott, H.-R.; Oseroff, S.B.; Goodrich, R.G.; Zysler, R. High-temperature weak ferromagnetism in a low-density free-electron gas. Nature 1999, 397, 412–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Denlinger, J.D.; Clack, J.A.; Allen, J.W.; Gweon, G.-H.; Poirier, D.M.; Olson, C.G.; Sarrao, J.L.; Bianchi, A.D.; Fisk, Z. Bulk Band Gaps in Divalent Hexaborides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 89, 157601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schmidt, K.M.; Jaime, O.; Cahill, J.T.; Edwards, D.; Misture, S.T.; Graeve, O.A.; Vasquez, V.R. Surface termination analysis of stoichiometric metal hexaborides: Insights from first-principles and XPS measurements. Acta Mater. 2018, 144, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etourneau, J.; Mercurio, J.-P.; Hagenmuller, P. Compounds Based on Octahedral B6 Units: Hexaborides and Tetraborides. In Boron and Refractory Borides; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1977; pp. 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.W.; Daane, A.H. Electron Requirements of Bonds in Metal Borides. J. Chem. Phys. 1963, 38, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Katsura, Y.; Yamamoto, A.; Ogino, H.; Horii, S.; Shimoyama, J.-I.; Kishio, K.; Takagi, H. On the possibility of MgB2-like superconductivity in potassium hexaboride. Phys. C Supercond. Its Appl. 2010, 470, S633–S634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, J.T.; Graeve, O.A. Hexaborides: A review of structure, synthesis and processing. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 6321–6335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.C.; van Lierop, J.; Berkeley, E.M.; Mansfield, J.F.; Henderson, C.; Aronson, M.C.; Young, D.P.; Bianchi, A.; Fisk, Z.; Balakirev, F.; et al. Weak ferromagnetism in CaB6. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 69, 132407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, K. Role of vacancies and impurities in the ferromagnetism of semiconducting CaB6. Europhys. Lett. 2008, 82, 67006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ackland, K.; Venkatesan, M.; Coey, J.M.D. Magnetism of BaB6 thin films synthesized by pulsed laser deposition. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 111, 07A322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, L.; Qi, X.; Tana, T.; Chao, L.; Tegus, O. Effects of induced optical tunable and ferromagnetic behaviors of Ba doped nanocrystalline LaB6. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 19165–19172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, D.; Young, D.P.; Fisk, Z.; Murphy, T.P.; Palm, E.C.; Teklu, A.; Goodrich, R.G. Fermi-surface measurements on the low-carrier density ferromagnet Ca1−xLaxB6 and SrB6. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 64, 233105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stankiewicz, J.; Schlottmann, P.; Arauzo, A.; Perez, M.J.M.; Rosa, P.F.S.; Civale, L.; Fisk, Z. Localized magnetic moments in metallic SrB6 single crystals. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2018, 31, 065602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muñoz, M.C.; Gallego, S.; Sanchez, N. Surface ferromagnetism in non-magnetic and dilute magnetic oxides. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2011, 303, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Wang, W.-P.; Xie, Z.; Zhan, P.; Li, Z.-C.; Zhang, Z.-J. Room temperature ferromagnetism in un-doped amorphous HfO 2 nano-helix arrays. Chin. Phys. B 2015, 24, 057503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, G.; Yunoki, S. Surface ferromagnetism in HfO2 induced by excess oxygen. Solid State Commun. 2017, 252, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straumal, B.B.; Protasova, S.G.; Mazilkin, A.A.; Goering, E.; Schütz, G.; Straumal, P.B.; Baretzky, B. Ferromagnetic behaviour of ZnO: The role of grain boundaries. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2016, 7, 1936–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dietl, T.; Ohno, H.; Matsukura, F.; Cibert, J.; Ferrand, D. Zener Model Description of Ferromagnetism in Zinc-Blende Magnetic Semiconductors. Science 2000, 287, 1019–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sato, K.; Katayama-Yoshida, H. First principles materials design for semiconductor spintronics. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2002, 17, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straumal, B.B.; Mazilkin, A.A.; Protasova, S.G.; Myatiev, A.A.; Straumal, P.B.; Schütz, G.; van Aken, P.A.; Goering, E.; Baretzky, B. Magnetization study of nanograined pure and Mn-doped ZnO films: Formation of a ferromagnetic grain-boundary foam. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 79, 205206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pazhanivelu, V.; Blessington Selvadurai, A.P.; Murugaraj, R. Unexpected ferromagnetism in Ist group elements doped ZnO based DMS nanoparticles. Mater. Lett. 2015, 151, 112–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, J.; Xu, Y.; Qi, J.; Xue, D. Room temperature ferromagnetism of pure ZnO nanoparticles. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 105, 113928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zong, Y.; Feng, J.; Li, X.; Yan, F.; Lan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ren, Z.; Zheng, X. Oxygen vacancies driven size-dependent d0 room temperature ferromagnetism in well-dispersed dopant-free ZnO nanoparticles and density functional theory calculation. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 739, 1080–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaee, A.; Mostafavi, A.; Shamspur, T.; Fathirad, F. Green synthesis of cerium oxide nanoparticles: Characterization, parameters optimization and investigation of photocatalytic application. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem 2020, 10, 5932–5937. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Lee, J.; Yoo, H.-I. Oxygen-vacancy-induced ferromagnetism in CeO2 from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 79, 100403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killivalavan, A.; Prabakar, A.C.; Chandra Babu, K.; Naidu, B.; Sathyaseelan, G.; Rameshkumar, D.; Sivakumar, K.; Senthilnathan, I.; Baskaran, E.; Manikandan, B.R.R. Synthesis and characterization of pure and Cu doped CeO2 nanoparticles: Photocatalytic and antibacterial activities evaluation. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem 2020, 10, 5306–5311. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Lockman, Z.; Aziz, A.; MacManus-Driscoll, J. Size dependent ferromagnetism in cerium oxide (CeO2) nanostructures independent of oxygen vacancies. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2008, 20, 165201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, V.; Mossanek, R.J.O.; Schio, P.; Klein, J.J.; De Oliveira, A.J.A.; Ortiz, W.A.; Mattoso, N.; Varalda, J.; Schreiner, W.H.; Abbate, M.; et al. Dilute-defect magnetism: Origin of magnetism in nanocrystalline CeO2. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 80, 035202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.P.; Chae, K.H. d° Ferromagnetism of Magnesium Oxide. Condens. Matter 2017, 2, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Araujo, C.M.; Kapilashrami, M.; Jun, X.; Jayakumar, O.D.; Nagar, S.; Wu, Y.; Århammar, C.; Johansson, B.; Belova, L.; Ahuja, R.; et al. Room temperature ferromagnetism in pristine MgO thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 96, 232505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, D.; Xu, Y.; Yan, M. Origin of room temperature ferromagnetism in MgO films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 102, 072406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadeva, S.K.; Fan, J.; Biswas, A.; Sreelatha, K.S.; Belova, L.; Rao, K.V. Magnetism of Amorphous and Nano-Crystallized Dc-Sputter-Deposited MgO Thin Films. Nanomaterials 2013, 3, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, D.; Hong, J.; Park, Y.R.; Kim, K.J. The origin of oxygen vacancy induced ferromagnetism in undoped TiO2. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2009, 21, 195405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wang, X.; Tao, L.L.; Song, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Sui, Y.; Liu, Z.; Tang, J.; Han, X.F. Effect of Ga-doping and oxygen vacancies on the ferromagnetism of TiO2 thin films. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 694, 929–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santara, B.; Pal, B.; Giri, P.K. Signature of strong ferromagnetism and optical properties of Co doped TiO2 nanoparticles. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 110, 114322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.; Zeng, Y.-P.; Jiang, D.; Masuda, Y. Room Temperature Ferromagnetism in Transition Metal Doped TiO2 Nanowires. Sci. Adv. Mater. 2009, 1, 227–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, E.; Puigdollers, A.R.; Pacchioni, G. Theory of Ferromagnetism in Reduced ZrO2–x Nanoparticles. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 5301–5307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, S.; Zhan, P.; Xie, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z. Room-temperature ferromagnetism in un-doped ZrO2 thin films. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2013, 46, 445004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, N.H.; Park, C.-K.; Raghavender, A.T.; Ciftja, O.; Bingham, N.S.; Phan, M.H.; Srikanth, H. Room temperature ferromagnetism in monoclinic Mn-doped ZrO2 thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 111, 07C302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Bai, G.; Jiang, Y.; Du, Y.; Wu, C.; Yan, M. Origin of room temperature ferromagnetism in SnO2 films. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2017, 426, 545–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Dai, Z.X.; Zeng, Z. Search for ferromagnetism in SnO2 doped with transition metals (V, Mn, Fe, and Co). J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2008, 20, 045214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Janani, M.; Srikrishnarka, P.; Nair, S.V.; Nair, A.S. An in-depth review on the role of carbon nanostructures in dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 17914–17938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Y.; Liang, J.; Chen, Y. Room-Temperature Ferromagnetism of Graphene. Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevenilir, E.; Kincal, C.; Kamber, U.; Guerlue, O.; Yildiz, D.; Grygiel, C.; Van der Beek, C.J. Investigation of ferromagnetism on graphite due to swift heavy ion irradiation. Verh. Dtsch. Phys. Ges. 2017, 50, 50004365. [Google Scholar]

- Céspedes, O.; Ferreira, M.S.; Sanvito, S.; Kociak, M.; Coey, J.M.D. Contact induced magnetism in carbon nanotubes. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2004, 16, L155–L161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, A.L.; Chun, H.; Jung, Y.J.; Heiman, D.; Glaser, E.R.; Menon, L. Possible room-temperature ferromagnetism in hydrogenated carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81, 115461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Xiong, L.; Zhang, F.; Fu, Q.; Ma, Z.; Xu, C.; Lin, Z.; Wang, H.; Hu, Z.; et al. Enhanced ferromagnetic properties of N2 plasma-treated carbon nanotubes. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 2307–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.W.; Lee, K.W.; Lee, C.E. Defect-induced room-temperature ferromagnetism in single-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2018, 460, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroto, H.W.; Heath, J.R.; O’Brien, S.C.; Curl, R.F.; Smalley, R.E. C60: Buckminsterfullerene. Nature 1985, 318, 162–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höhne, R.; Esquinazi, P. Can Carbon Be Ferromagnetic? Adv. Mater. 2002, 14, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ata, M.; Machida, M.; Watanabe, H.; Seto, J. Polymer-C60 Composite with Ferromagnetism. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1994, 33, 1865–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, T. Magnetism in Polymerized Fullerenes. In Frontiers of Multifunctional Integrated Nanosystems; Buzaneva, E., Scharff, P., Eds.; NATO Science Series II: Mathematics, Physics and Chemistry; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 152, pp. 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, T.L.; Sundqvist, B. Pressure-induced ferromagnetism of fullerenes. High Press. Res. 2003, 23, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R.A.; Lewis, M.H.; Lees, M.R.; Bennington, S.M.; Cain, M.G.; Kitamura, N. Ferromagnetic fullerene. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2002, 14, L385–L391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Tongay, S.; Hebard, A.F.; Sahin, H.; Peeters, F.M. Ferromagnetism in stacked bilayers of Pd/C60. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2014, 349, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazyev, O.V.; Helm, L. Defect-induced magnetism in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 75, 125408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nuckolls, K.P.; Oh, M.; Wong, D.; Lian, B.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Bernevig, B.A.; Yazdani, A. Strongly correlated Chern insulators in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Nature 2020, 588, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.L.; Meng, S.; Kaxiras, E. Graphene NanoFlakes with Large Spin. Nano Lett. 2007, 8, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, V.; Maurya, V.K.; Singh, G.; Patnaik, S.; Sharma, R.K. Enhanced ferromagnetism in edge enriched holey/lacey reduced graphene oxide nanoribbons. Mater. Des. 2017, 132, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mombrú, A.W.; Pardo, H.; Faccio, R.; de Lima, O.F.; Leite, E.R.; Zanelatto, G.; Lanfredi, A.J.C.; Cardoso, C.A.; Araújo-Moreira, F.M. Multilevel ferromagnetic behavior of room-temperature bulk magnetic graphite. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 71, 100404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, Z.; Xia, H.; Zhou, X.; Yang, X.; Song, Y.; Wang, T. Raman study of correlation between defects and ferromagnetism in graphite. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2011, 44, 085001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xia, H.; Qin, X.; Li, W.; Dai, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhao, M.; Xia, Y.; Yan, S.; Wang, B. Correlation between the vacancy defects and ferromagnetism in graphite. Carbon 2009, 47, 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, R.; Lech, A.T.; Xie, M.; Weaver, B.E.; Yeung, M.T.; Tolbert, S.H.; Kaner, R.B. Tungsten tetraboride, an inexpensive superhard material. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 10958–10962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tang, C.; Ostrikov, K.; Sanvito, S.; Du, A. Prediction of room-temperature ferromagnetism and large perpendicular magnetic anisotropy in a planar hypercoordinate FeB3 monolayer. Nanoscale Horiz. 2021, 6, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Ram, S.; Srinivas, V. Ferromagnetic nickel filled in borate shell by controlled oxidation–crystallization of boride in air. J. Alloys Compd. 2014, 610, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieschang, A.-M.; Bocarsly, J.D.; Schuch, J.; Reichel, C.V.; Kaiser, B.; Jaegermann, W.; Seshadri, R.; Albert, B. Magnetic and Electrocatalytic Properties of Nanoscale Cobalt Boride, Co3B. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 16609–16617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peng, H.; Xiang, H.J.; Wei, S.-H.; Li, S.-S.; Xia, J.-B.; Li, J. Origin and Enhancement of Hole-Induced Ferromagnetism in First-Row d0 Semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 017201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminski, A.; Das Sarma, S. Polaron Percolation in Diluted Magnetic Semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 247202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schwerdt, J.I.; Goya, G.F.; Calatayud, M.P.; Herenu, C.B.; Reggiani, P.C.; Goya, R.G. Magnetic field-assisted gene delivery: Achievements and therapeutic potential. Curr. Gene Ther. 2012, 12, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedelkoski, Z.; Kepaptsoglou, D.; Lari, L.; Wen, T.; Booth, R.A.; Oberdick, S.D.; Galindo, P.L.; Ramasse, Q.M.; Evans, R.F.L.; Majetich, S.; et al. Origin of reduced magnetization and domain formation in small magnetite nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.; Zhang, L.; Hu, L.; Yu, H.; Min, G.; Yu, H. Structure and magnetic properties of nanocrystalline CaB6 films deposited by magnetron sputtering. J. Alloys Compd. 2014, 599, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, C.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Q.; Eom, C.-B. Surface magnetism and proximity effects in hexaboride thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 110, 102404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qi, L.-Q.; Han, R.-S.; Liu, L.-H.; Sun, H.-Y. Preparation and magnetic properties of DC-sputtered porous HfO2 films. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 18925–18930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, P.; Wang, W.; Liu, C.; Hu, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Wang, B.; Cao, X. Oxygen vacancy–induced ferromagnetism in un-doped ZnO thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 111, 033501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Huang, Y.; Wu, P. Unexpected ferromagnetism in n-type polycrystalline K-doped ZnO films prepared by RF-magnetron sputtering. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2015, 26, 8451–8455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.-L.; Zhang, Y.D.; Yang, D.S.; Nghia, N.X.; Thanh, T.D.; Yu, S.C. Defect-induced ferromagnetism in ZnO nanoparticles prepared by mechanical milling. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 102, 072408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, J.; Pradhan, S.K.; Mishra, D.K.; Sahu, D.R.; Sarangi, S.; Varma, S.; Nayak, B.B.; Huang, J.-L.; Roul, B.K. Unusual ferromagnetism in high purity ZnO sintered ceramics. Mater. Res. Bull. 2011, 46, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumaiz, A.K.; Ali, B.; Ceylan, A.; Boggs, M.; Beebe, T.; Ismat Shah, S. Experimental studies on vacancy induced ferromagnetism in undoped TiO2. Solid State Commun. 2007, 144, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singhal, R.K.; Kumar, S.; Kumari, P.; Xing, Y.T.; Saitovitch, E. Evidence of defect-induced ferromagnetism and its “switch” action in pristine bulk TiO2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 98, 092510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangaletti, L.; Mozzati, M.C.; Galinetto, P.; Azzoni, C.B.; Speghini, A.; Bettinelli, M.; Calestani, G. Ferromagnetism on a paramagnetic host background: The case of rutile TM:TiO2 single crystals (TM = Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu). J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2006, 18, 7643–7650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, K.; Xie, Y.; Xu, L.; Yan, B. Structure and magnetic properties of ZrO2-coated Fe powders and Fe/ZrO2 soft magnetic composites. Adv. Powder Technol. 2017, 28, 2015–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Gao, D.; Xu, Q.; Yang, Z.; Xue, D. Singly-charged oxygen vacancy-induced ferromagnetism in mechanically milled SnO2 powders. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 45467–45472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehraj, S.; Ansari, M.S.; Al-Ghamdi, A.A. Alimuddin Annealing dependent oxygen vacancies in SnO2 nanoparticles: Structural, electrical and their ferromagnetic behavior. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2016, 171, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Srinivas, V. Evolution of Ni:B2O3 core-shell structure and magnetic properties on devitrification of amorphous NiB particles in air. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 106, 053910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiping, L.; Hadjipanayis, G.C.; Sorensen, C.M.; Klabunde, K.J. Magnetic and structural properties of ultrafine Co-B particles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1989, 79, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Pan, F. Transition Metal-Doped Magnetic Oxides. Semicond. Semimet. 2013, 88, 227–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S.A.; Awschalom, D.D.; Buhrman, R.A.; Daughton, J.M.; von Molnár, S.; Roukes, M.L.; Chtchelkanova, A.Y.; Treger, D.M. Spintronics: A Spin-Based Electronics Vision for the Future. Science 2001, 294, 1488–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sinova, J.; Žutić, I. New moves of the spintronics tango. Nat. Mater. 2012, 11, 368–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, K.; Jung, H.N.; Lee, J.W.; Xu, S.; Liu, Y.H.; Ma, Y.; Jeong, J.; Song, Y.M.; Kim, J.; Kim, B.H.; et al. Ferromagnetic, Folded Electrode Composite as a Soft Interface to the Skin for Long-Term Electrophysiological Recording. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 7281–7290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stretchable Bioelectronics for Medical Devices and Systems; Rogers, J.A.; Ghaffari, R.; Kim, D.-H. (Eds.) Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corá, L.A.; Américo, M.F.; Oliveira, R.B.; Serra, C.H.R.; Baffa, O.; Evangelista, R.C.; Oliveira, G.F.; Miranda, J.R.A. Biomagnetic Methods: Technologies Applied to Pharmaceutical Research. Pharm. Res. 2010, 28, 438–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulens, V.; del Puerto Morales, M.; Barber, D.F. Development of Magnetic Nanoparticles for Cancer Gene Therapy: A Comprehensive Review. ISRN Nanomater. 2013, 2013, 646284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laosiritaworn, W.; Chotchaithanakorn, N. Artificial neural networks parameters optimization with design of experiments: An application in ferromagnetic materials modeling. Chiang Mai J. Sci. 2009, 36, 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Borders, W.A.; Akima, H.; Fukami, S.; Moriya, S.; Kurihara, S.; Horio, Y.; Sato, S.; Ohno, H. Analogue spin–orbit torque device for artificial-neural-network-based associative memory operation. Appl. Phys. Express 2016, 10, 013007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukami, S.; Ohno, H. Perspective: Spintronic synapse for artificial neural network. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 124, 151904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mantovan, R.; Gunnlaugsson, H.P.; Johnston, K.; Masenda, H.; Mølholt, T.E.; Naidoo, D.; Ncube, M.; Shayestehaminzadeh, S.; Bharuth-Ram, K.; Fanciulli, M.; et al. Atomic-Scale Magnetic Properties of Truly 3d-Diluted ZnO. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2015, 1, 1400039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, B.; Ólafsson, S.; Gíslason, H.P. Vacancy defect-induced d0 ferromagnetism in undoped ZnO nanostructures: Controversial origin and challenges. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2017, 90, 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.M.C. Experimentally evaluating the origin of dilute magnetism in nanomaterials. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2017, 50, 393002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, J.; Voigt, B.; Day-Roberts, E.; Heltemes, K.; Fernandes, R.M.; Birol, T.; Leighton, C. Voltage-induced ferromagnetism in a diamagnet. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabb7721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).