Iron Speciation in Insoluble Dust from High-Latitude Snow: An X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

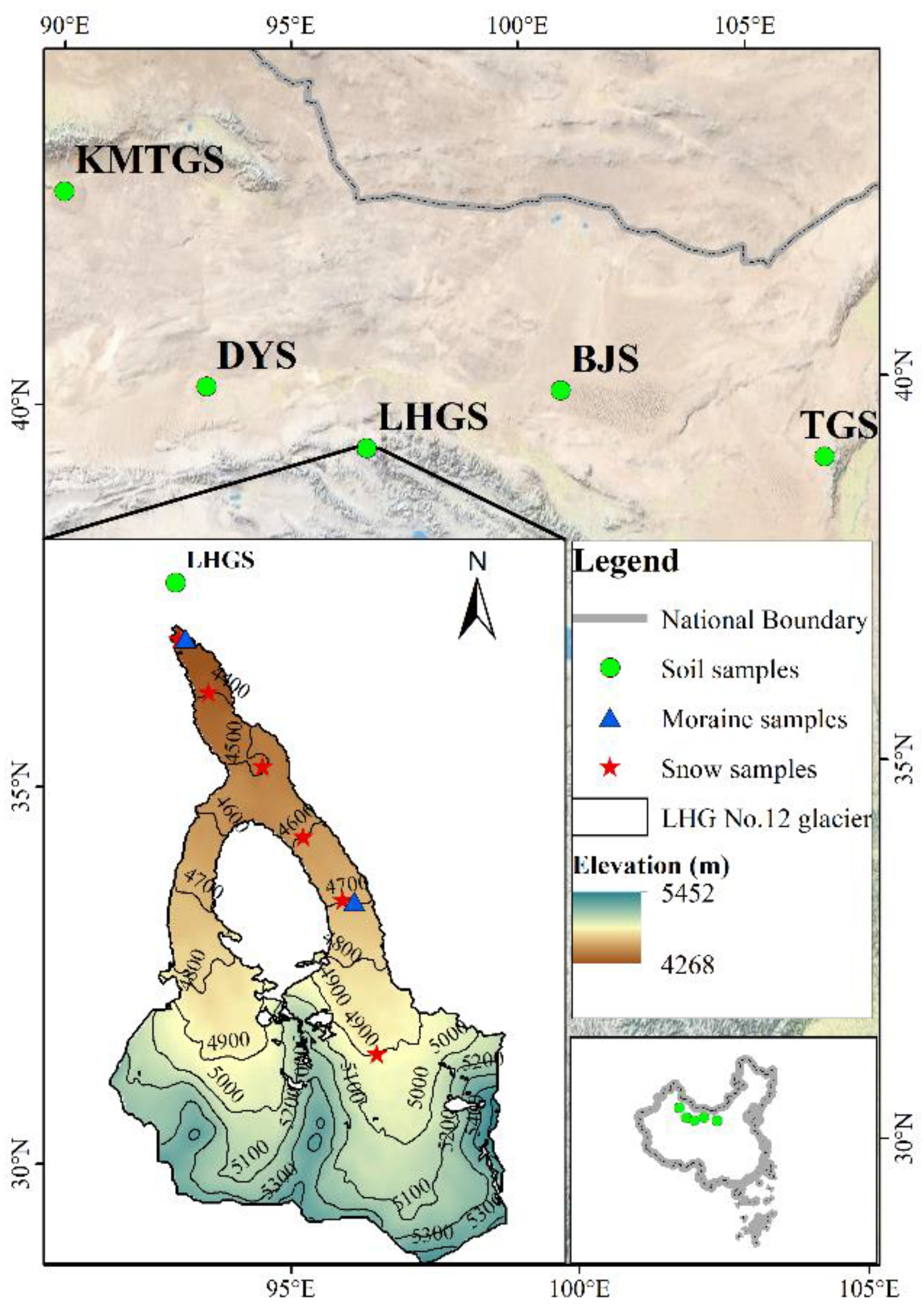

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Choice of Reference Compounds

2.3. X-ray Absorption Measurements

3. Results and Discussions

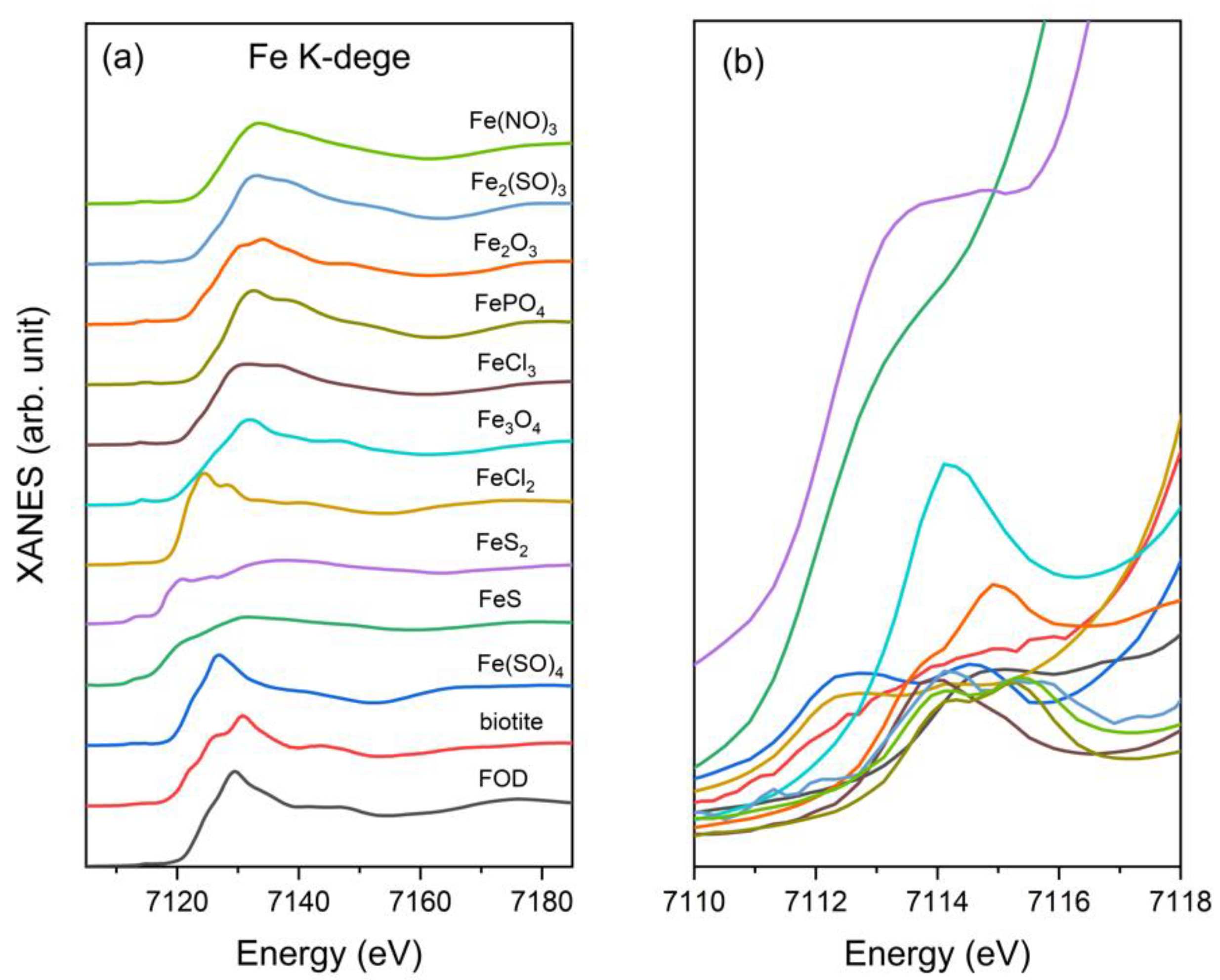

3.1. Fe K-Edge XANES of Standards

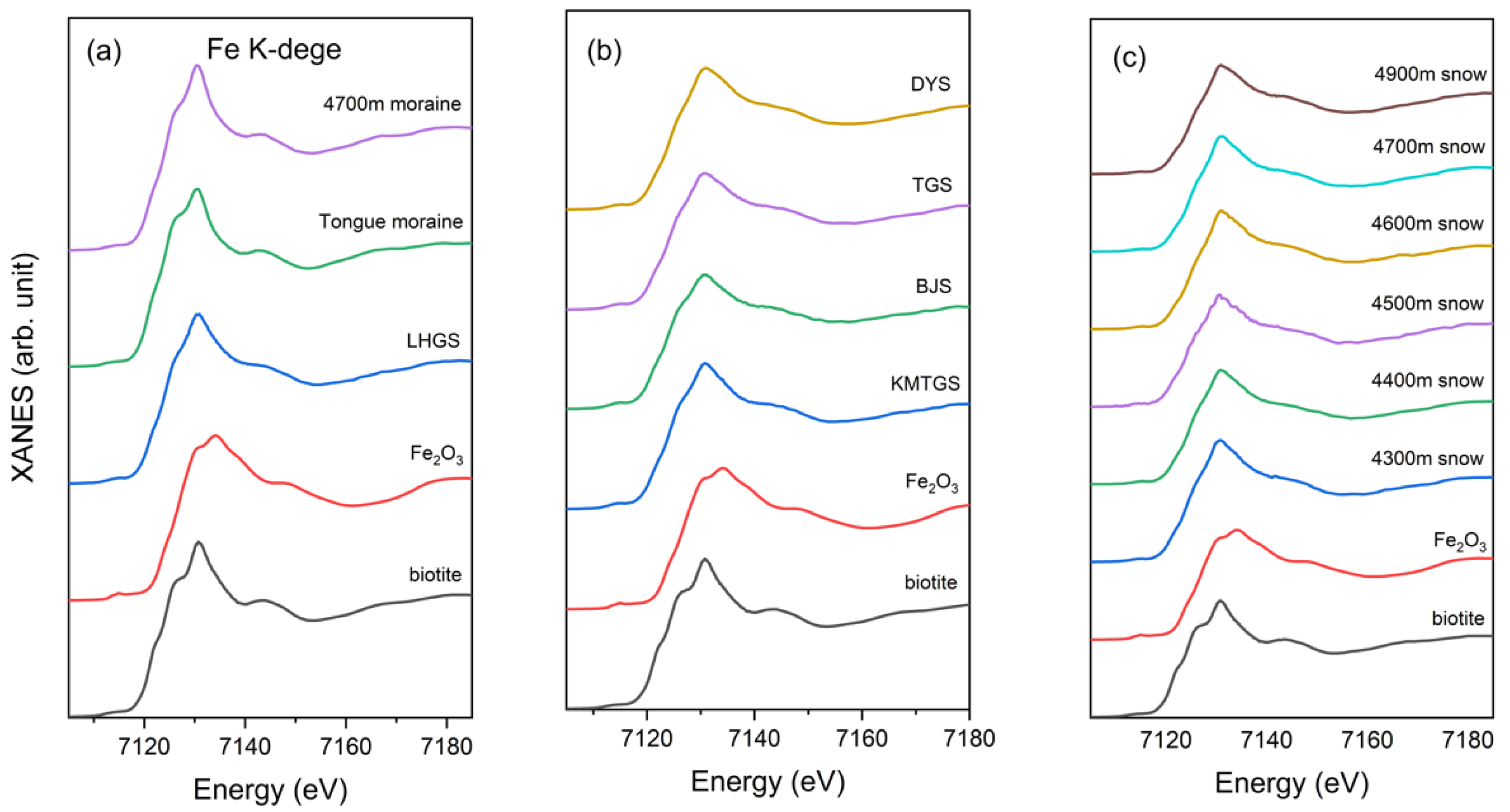

3.2. Fe K-Edge XANES of the Soil, Moraine, and Snow Samples

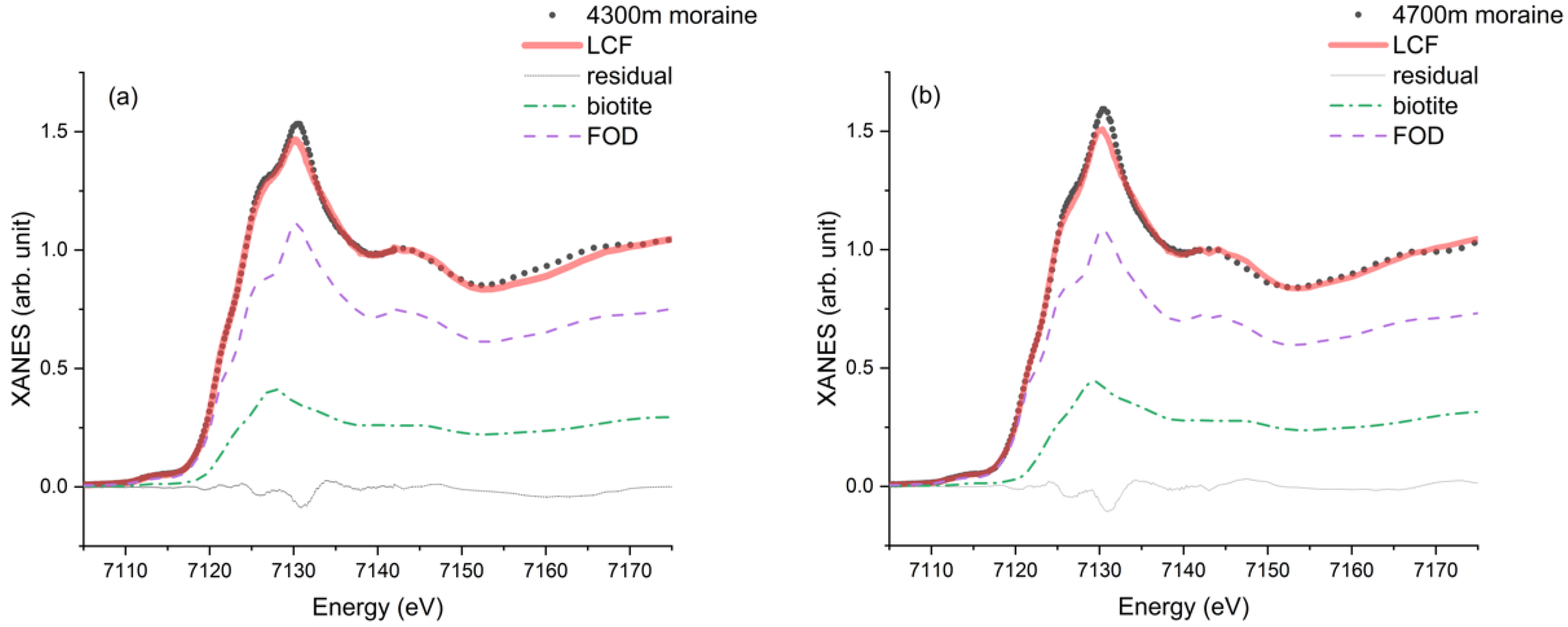

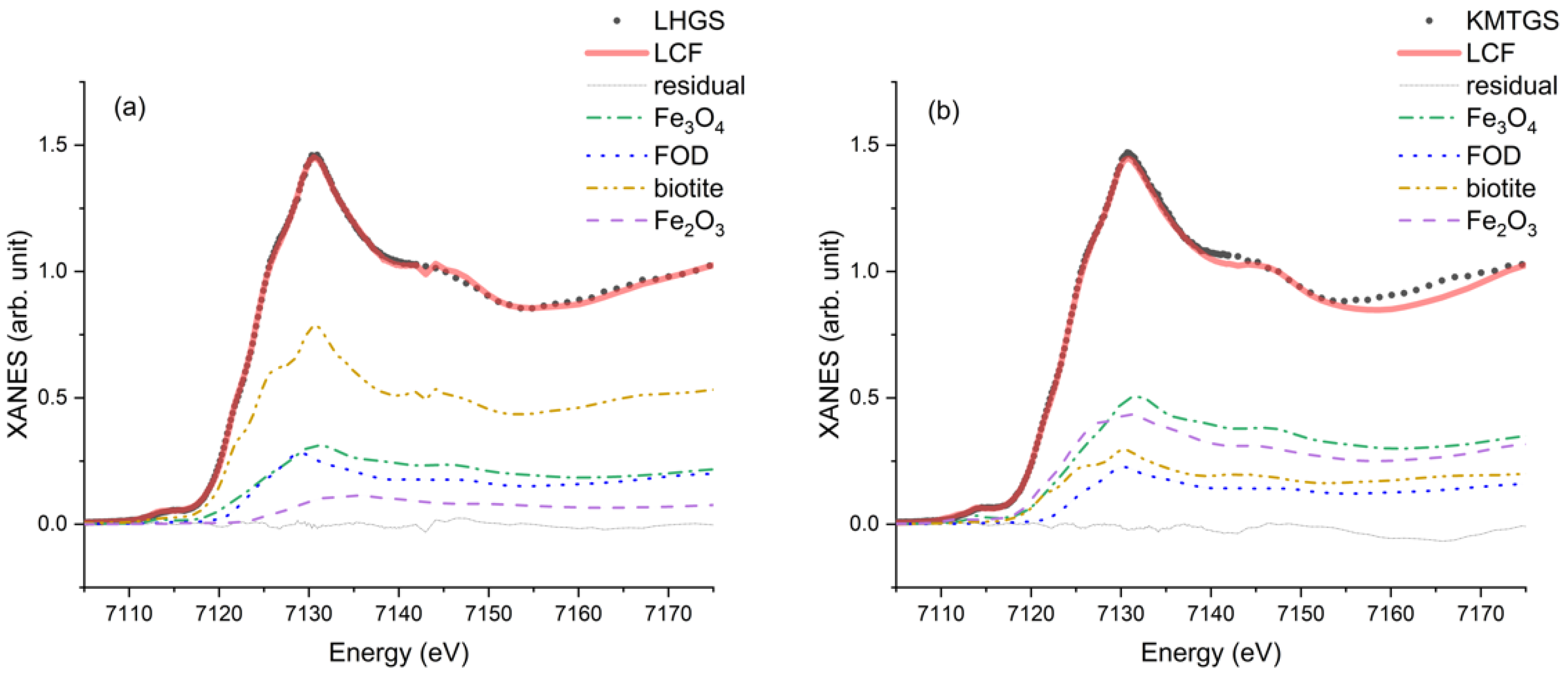

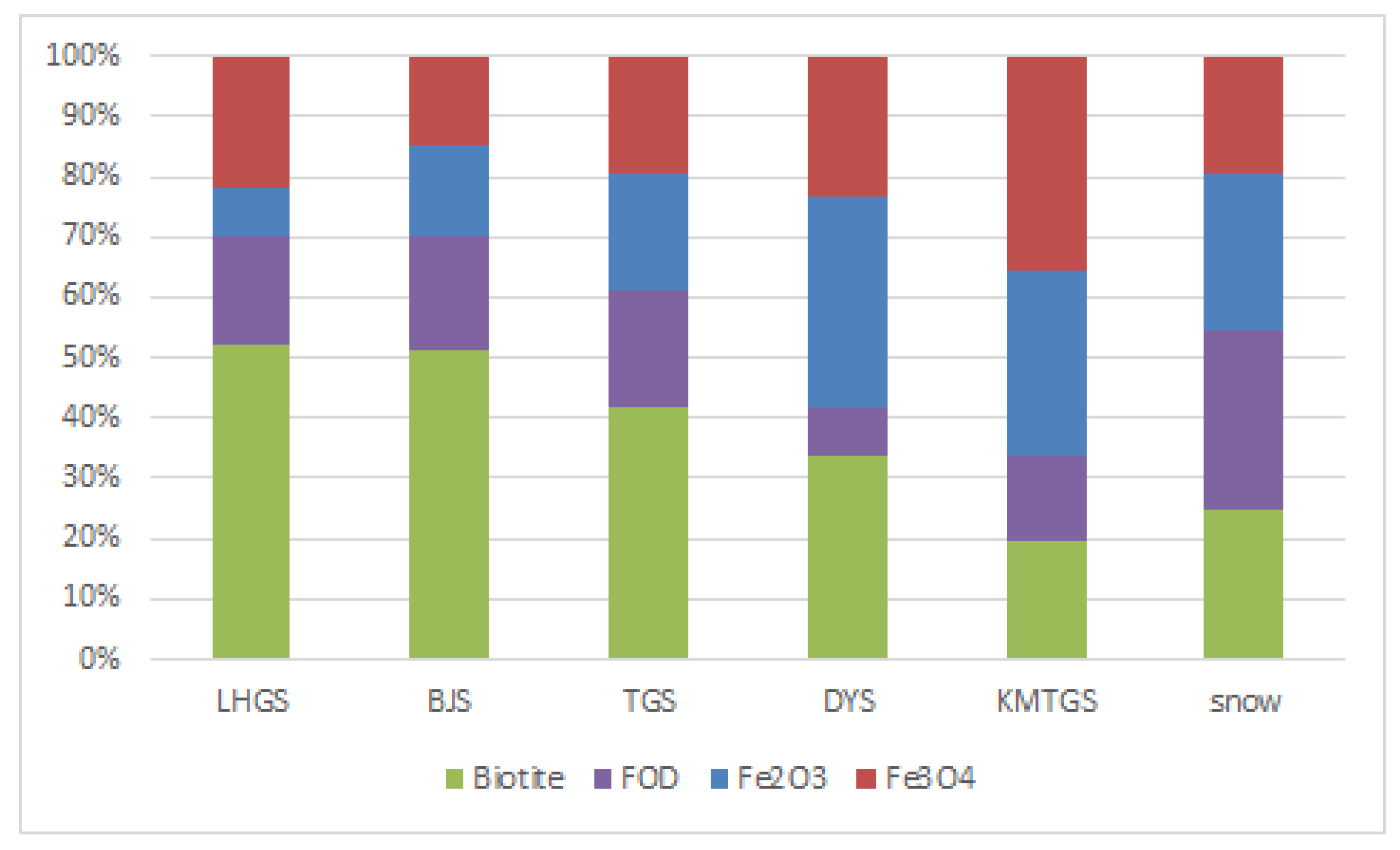

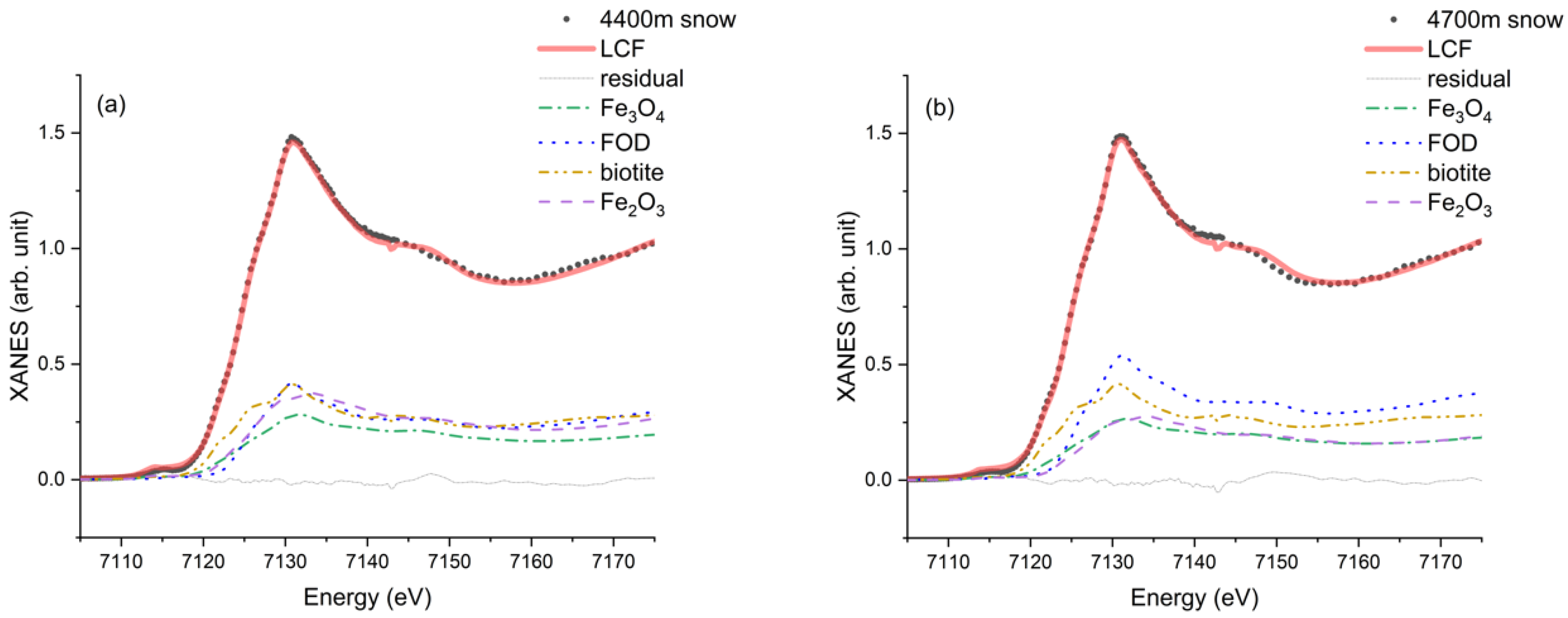

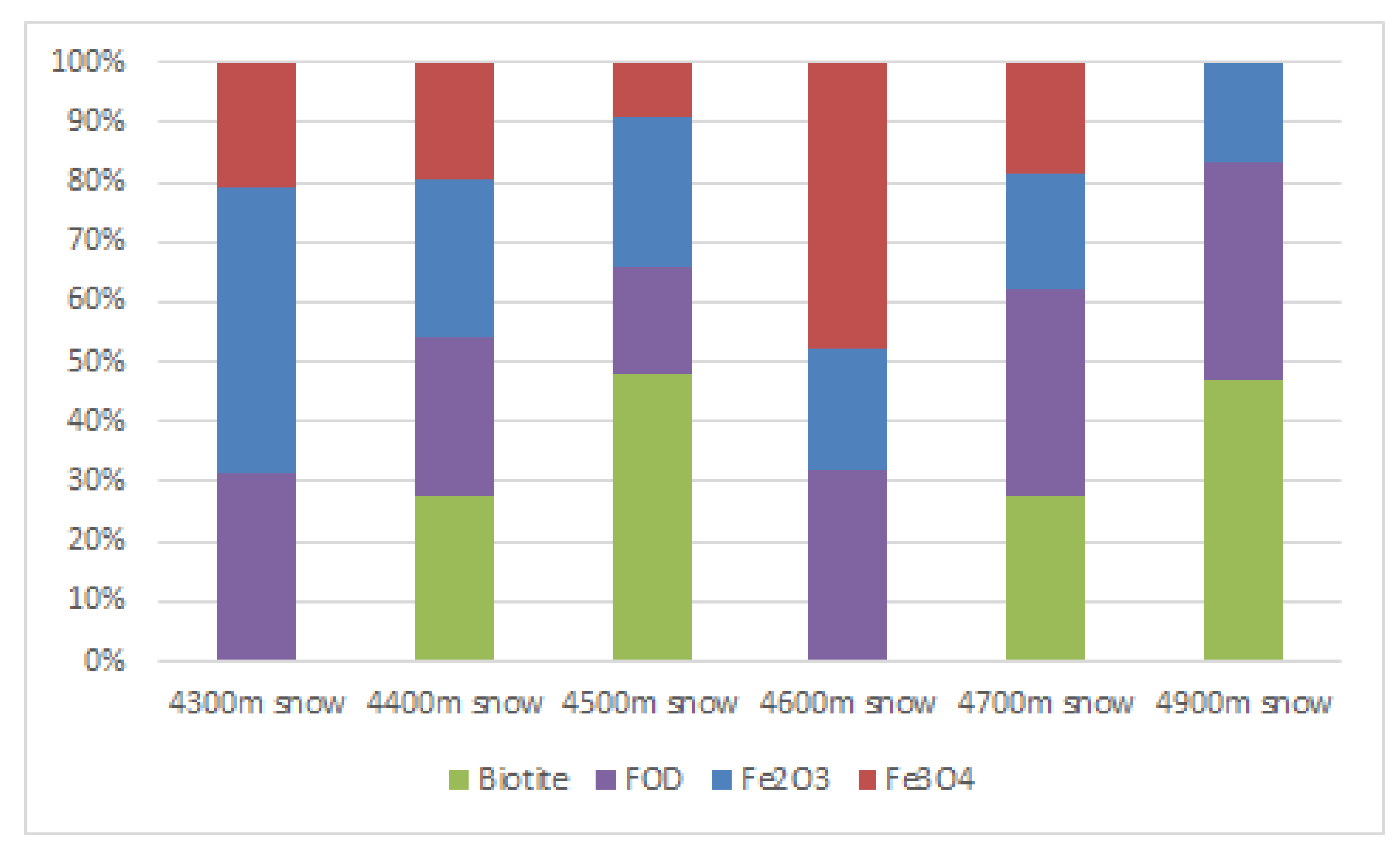

3.3. Linear Combination Fitting

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allen, B.L.; Hajek, B.F. Mineral occurrence in soil environments. Miner. Soil Environ. 1989, 28, 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Blume, H.P.; Schwertmann, U. Genetic evaluation of profile distribution of aluminum, iron, and manganese oxides 1. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1969, 33, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, R.M. The iron oxides. In Soil Mineralogy with Environmental Applications; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; pp. 363–369. [Google Scholar]

- Schwertmann, U. Relations between iron oxides, soil color, and soil formation. Soil Color 1993, 31, 51–69. [Google Scholar]

- Schwertmann, U.; Schwertmann, U.; Lentze, W. Bodenfarbe und eisenoxidform. Z. Pflanzenernährung Düngung Bodenkd. 1966, 115, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheinost, A.; Schwertmann, U. Color identification of iron oxides and hydroxysulfatesuse and limitations. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1999, 5, 1463–1471. [Google Scholar]

- Schwertmann, U.; Fechter, H. The point of zero charge of natural and synthetic ferrihydrites and its relation to adsorbed silicate. Clay Miner. 1982, 17, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, O.; Jackson, M. Iron oxide removal from soils and clays by a dithionite–citrate system buffered with sodium bicarbonate. In Proceedings of the Seventh National Conference on Clays and Clay Minerals; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1960; pp. 317–327. [Google Scholar]

- Schwertmann, U. Differenzierung der eisenoxide des bodens durch extraktion mit ammoniumoxalat-lösung. Z. Pflanzenernährung Düngung Bodenkd. 1964, 105, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmgren, G.G. A rapid citrate-dithionite extractable iron procedure 1. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1967, 31, 210–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vold, M.J. Differential thermal analysis. Anal. Chem. 1949, 21, 683–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xu, L.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Lin, Y.; Yao, X.; Gao, H.; Zhang, D.; Chen, J.; Wang, W. Air pollution–aerosol interactions produce more bioavailable iron for ocean ecosystems. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1601749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belli, M.; Scafati, A.; Bianconi, A.; Mobilio, S.; Palladino, L.; Reale, A.; Burattini, E. X-ray absorption near edge structures (xanes) in simple and complex mn compounds. Solid State Commun. 1980, 35, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianconi, A.; Dell’Ariccia, M.; Durham, P.J.; Pendry, J.B. Multiple-scattering resonances and structural effects in the x-ray-absorption near-edge spectra of fe ii and fe iii hexacyanide complexes. Phys. Rev. B 1982, 26, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachrach, R.Z. Synchrotron Radiation Research: Advances in Surface and Interface Science; Kluwer Academic: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatek, W.; Gałka, M.; Hanson, A.; Paluszkiewicz, C.; Cichocki, T. Xanes as a tool for iron oxidation state determination in tissues. J. Alloys Compd. 2001, 328, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajt, S.; Sutton, S.; Delaney, J. X-ray microprobe analysis of iron oxidation states in silicates and oxides using x-ray absorption near edge structure (xanes). Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1994, 58, 5209–5214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galoisy, L.; Calas, G.; Arrio, M. High-resolution xanes spectra of iron in minerals and glasses: Structural information from the pre-edge region. Chem. Geol. 2001, 174, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prietzel, J.; Thieme, J.; Eusterhues, K.; Eichert, D. Iron speciation in soils and soil aggregates by synchrotron-based x-ray microspectroscopy (xanes, μ-xanes). Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2007, 58, 1027–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ressler, T.; Wong, J.; Joseph Roos, A.; Smith§, I.L. Quantitative speciation of mn-bearing particulates emitted from autos burning (methylcyclopentadienyl)manganese tricarbonyl-added gasolines using xanes spectroscopy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2000, 34, 950–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Higashi, M.; Furukawa, T.; Mitsunobu, S. Change of iron species and iron solubility in asian dust during the long-range transport from western china to japan. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011, 11, 11237–11252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraal, P.; Burton, E.D.; Rose, A.L.; Kocar, B.D.; Lockhart, R.S.; Grice, K.; Bush, R.T.; Tan, E.; Webb, S.M. Sedimentary iron–phosphorus cycling under contrasting redox conditions in a eutrophic estuary. Chem. Geol. 2015, 392, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y. Concise Glacier Inventory of China; Shanghai Popular Science Press: Shanghai, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- d’Acapito, F.; Trapananti, A.; Puri, A. Lisa: The italian crg beamline for x-ray absorption spectroscopy at esrf. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2016, 712, 012021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Acapito, F. Lisa Annual Report 2017; CNR-IOM: Grenoble, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ravel, B.; Newville, M. Athena, artemis, hephaestus: Data analysis for x-ray absorption spectroscopy using ifeffit. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2010, 12, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winterer, M. Xafs—A data analysis program for materials science. J. Phys. IV 1997, 7, C2-243–C2-244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coale, K.H.; Johnson, K.S.; Fitzwater, S.E.; Gordon, R.M.; Tanner, S.; Chavez, F.P.; Ferioli, L.; Sakamoto, C.; Rogers, P.; Millero, F. A massive phytoplankton bloom induced by an ecosystem-scale iron fertilization experiment in the equatorial pacific ocean. Nature 1996, 383, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jickells, T.D.; An, Z.S.; Andersen, K.K.; Baker, A.R.; Bergametti, G.; Brooks, N.; Cao, J.J.; Boyd, P.W.; Duce, R.A.; Hunter, K.A.; et al. Global iron connections between desert dust, ocean biogeochemistry, and climate. Science 2005, 308, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahowald, N.M.; Engelstaedter, S.; Luo, C.; Sealy, A.; Artaxo, P.; Beniteznelson, C.; Bonnet, S.; Chen, Y.; Chuang, P.Y.; Cohen, D.D. Atmospheric iron deposition: Global distribution, variability, and human perturbations. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2009, 1, 245–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noël, V.; Marchand, C.; Juillot, F.; Ona-Nguema, G.; Viollier, E.; Marakovic, G.; Olivi, L.; Delbes, L.; Gelebart, F.; Morin, G. Exafs analysis of iron cycling in mangrove sediments downstream a lateritized ultramafic watershed (vavouto bay, new caledonia). Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2014, 136, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Name | Substance Configuration | Collecting Location |

|---|---|---|

| LHGS | soil | End of the LHG No.12 glacier |

| KMTGS | sand | Kumtag desert |

| DYS | soil | Dunhuang yadan |

| TGS | sand | Tengger desert |

| BJS | sand | Badain Jaran desert |

| Tongue moraine | moraine | 4250 m a.s.l. LHG No.12 glacier |

| 4700 m moraine | moraine | 4700 m a.s.l. LHG No.12 glacier |

| 4300 m snow | insoluble dust in snow | 4300 m a.s.l. LHG No.12 glacier |

| 4400 m snow | insoluble dust in snow | 4400 m a.s.l. LHG No.12 glacier |

| 4500 m snow | insoluble dust in snow | 4500 m a.s.l. LHG No.12 glacier |

| 4600 m snow | insoluble dust in snow | 4600 m a.s.l. LHG No.12 glacier |

| 4700 m snow | insoluble dust in snow | 4700 m a.s.l. LHG No.12 glacier |

| 4900 m snow | insoluble dust in snow | 4900 m a.s.l. LHG No.12 glacier |

| Samples | Fe2O3 | Fe3O4 | Biotite | FOD | R-Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion (Uncertainty) | |||||

| LHGS | 0.080 (0.025) | 0.218 (0.019) | 0.524 (0.013) | 0.178 (0.008) | 0.0002 |

| Tongue moraine | / | / | 0.738 (0.089) | 0.262 (0.102) | 0.0017 |

| 4700 m moraine | / | / | 0.719 (0.018) | 0.281 (0.018) | 0.0022 |

| KMTGS | 0.307 (0.061) | 0.354 (0.038) | 0.196 (0.034) | 0.143 (0.018) | 0.0010 |

| DYS | 0.346 (0.031) | 0.235 (0.026) | 0.338 (0.014) | 0.081 (0.008) | 0.0003 |

| TGS | 0.192 (0.018) | 0.197 (0.015) | 0.417 (0.010) | 0.194 (0.005) | 0.0002 |

| BJS | 0.151 (0.035) | 0.147 (0.026) | 0.514 (0.019) | 0.188 (0.009) | 0.0005 |

| 4300 m snow | 0.478 (0.094) | 0.208 (0.148) | / | 0.315 (0.050) | 0.0075 |

| 4400 m snow | 0.264 (0.058) | 0.197 (0.043) | 0.275 (0.027) | 0.264 (0.016) | 0.0006 |

| 4500 m snow | 0.248 (0.053) | 0.092 (0.042) | 0.479 (0.026) | 0.181 (0.019) | 0.0008 |

| 4600 m snow | 0.200 (0.114) | 0.479 (0.071) | / | 0.320 (0.036) | 0.0040 |

| 4700 m snow | 0.194 (0.036) | 0.187 (0.099) | 0.278 (0.028) | 0.341 (0.017) | 0.0009 |

| 4900 m snow | 0.168 (0.048) | / | 0.468 (0.027) | 0.365 (0.034) | 0.0044 |

| Compound | Fe Oxidation State | Centroid Pre-Edge Peak | Inflection Point Absorption Edge | White Line |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Position/eV | ||||

| biotite | +2 | 7114.9 | 7121.0 | 7127.9 |

| FOD | +2 | 7115.1 | 7121.0 | 7127.9 |

| FeSO4 | +2 | 7114.6 | 7120.5 | 7127.0 |

| FeS | +2 | 7113.2 | 7116.4 | 7131.8 |

| FeS2 | +2 | 7114.8 | 7116.6 | 7120.8 |

| FeCl2 | +2 | 7114.2 | 7119.4 | 7124.5 |

| Fe3O4 | +2/+3 | 7114.2 | 7128.3 | 7132.0 |

| FeCl3 | +3 | 7114.1 | 7126.3 | 7131.9 |

| FePO4 | +3 | 7115.2 | 7127.2 | 7132.6 |

| Fe2O3 | +3 | 7114.9 | 7125.9 | 7134.1 |

| Fe(SO4)3 | +3 | 7114.2 | 7128.6 | 7133.3 |

| Fe(NO4)3 | +3 | 7115.2 | 7127.3 | 7133.5 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, S.; Xiao, C.; Du, Z.; Marcelli, A.; Cibin, G.; Baccolo, G.; Zhu, Y.; Puri, A.; Maggi, V.; Xu, W. Iron Speciation in Insoluble Dust from High-Latitude Snow: An X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy Study. Condens. Matter 2018, 3, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/condmat3040047

Liu S, Xiao C, Du Z, Marcelli A, Cibin G, Baccolo G, Zhu Y, Puri A, Maggi V, Xu W. Iron Speciation in Insoluble Dust from High-Latitude Snow: An X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy Study. Condensed Matter. 2018; 3(4):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/condmat3040047

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Shiwei, Cunde Xiao, Zhiheng Du, Augusto Marcelli, Giannantonio Cibin, Giovanni Baccolo, Yingcai Zhu, Alessandro Puri, Valter Maggi, and Wei Xu. 2018. "Iron Speciation in Insoluble Dust from High-Latitude Snow: An X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy Study" Condensed Matter 3, no. 4: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/condmat3040047

APA StyleLiu, S., Xiao, C., Du, Z., Marcelli, A., Cibin, G., Baccolo, G., Zhu, Y., Puri, A., Maggi, V., & Xu, W. (2018). Iron Speciation in Insoluble Dust from High-Latitude Snow: An X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy Study. Condensed Matter, 3(4), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/condmat3040047