1. Introduction

China incorporates 32,000 km of coastline and about 4.73 million km

2 of sea area [

1] and possesses 7372 islands (only about 450 islands are inhabited) with a total area of 72,800 million km

2 [

2].Thus, China owns a wide variety of marine resources [

3]. Such geographical advantages have turned China into the predominant producer of wild and farmed fish (aquaculture), and the capture fishery is also developed [

4]; these advantages have also made China a staunch supporter of extraordinary marine biodiversity throughout the global village [

5]. Statistics computed up to the end of May 2022 demonstrate that China has identified more than 20,278 aquatic wildlife species (marine fishes included), 1384 species of fish in inland waters, and 724 species of wetland wildlife. In addition to more than 6000 vertebrate types, aquatic species account for around 70% of China’s marine life, and 92 varieties of fish have been classified as extinct, endangered, vulnerable, or rare in the wild [

6]. The statistics and environmental features of such resources present the current conditions of Chinese aquatic wildlife species and reflect the unique advantages of the growing marine fisheries in China. China’s fishing industry has expanded dramatically over the last three decades. This industry encompasses marine fisheries, and its growth is driven by supportive government policies and the rapidly increasing demand for marine piscaries resources. However, the phenomenal growth in China’s fishing industry depended extensively on the overutilization of China’s limited fishery resources [

7]. Unfortunately, the root cause of the unsustainable fishing industry is mainly attributed to the disputed ownership of regional and other waters [

8] and unscientific practices [

9], such as illegal, unreported, or unregulated fishing [

10]. The difficulties confronting the sustainability of the fishing industry also include the outward expansion of China’s marine fisheries [

11], the pressures of excessive urban development, ocean pollution, and land reclamation, as well as rather inadequate fisheries-specific legislation [

12]. Such concerns have resulted in the rapid depletion of marine fisheries in China’s domestic waters, posing a dire threat to the sustainable growth of Chinese fisheries [

7,

13].

The Chinese government and relevant practitioners have begun attending to the increasingly severe problems mentioned above. They offered practical solutions from the perspectives of their domains [

14,

15]. However, the problems mentioned above have generated immense sustainable development challenges for marine fisheries in the combined context of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road [

16] and the quest to build a community that shares a vision of the future of humanity. Therefore, the stated issues must be resolved dynamically and rationally. There is substantial published research on the sustainable development of marine fisheries [

17]. Such investigations comprise combinations of comparison studies of the marine governance and legal framework of different nations and the international trade mechanisms involved in the operation of marine fisheries. Most existing Chinese studies on sustainable development are generally limited to comprehensive governance and policy analyses [

18,

19]. The scant scholarly discussion has targeted legal issues (legislation, law enforcement, and administrative management) pertaining to the sustainable development of marine fisheries. Therefore, the importance and necessity of studying the sustainable development of marine fisheries from the legal perspective are prominently evident.

Given the above context, this paper attempts to contribute to the extant research from the legal perspective of the sustainable development of Chinese marine fisheries. It thus begins with an illustration of the legal associations between sustainable development theory and marine fisheries. It offers a brief overview of the current conditions of Chinese marine fisheries and their evolutionary trajectory, provides updated data analyses, and subsequently examines the legal regimens regulating China’s marine fisheries. Additionally, the paper explores the legal issues regarding the sustainable development of Chinese marine fisheries. It evaluates the challenges posed to sustainable development by the current management mechanisms and legal systems governing marine fisheries. The final segment of this paper postulates possible approaches to ensure the sustainable development of Chinese marine fisheries. It also posits new and reformed ideas and practices to ameliorate the sustainable development of marine fisheries from the legal aspect.

2. The Theory of Sustainable Development and Marine Fisheries

This section sequentially scrutinizes the following international instruments and Chinese domestic laws in chronological order for marine fisheries to examine the legal relationships between the theory of sustainable development and the operation of marine fisheries. It determines how sustainable development theory has been applied to legal procedures concerning marine fisheries.

The 1972 Declaration of the United Nations Conference on Human Environment [

20], the mooting of Our Common Future in 1987 [

21], the Rio Principles adopted in 1992 [

22], the Millennium Declaration of 2000 [

23], the 2002 Johannesburg Declaration [

24], and the 2005 World Summit Outcome Document [

25] represent international instruments that can essentially be deemed the soft international law on sustainable development adopted in the context of the United Nations. Without exception, these documents are intended to reinforce the foundations of international cooperation on sustainable development. Notwithstanding the oceans and marine resources mentioned intermittently in these international instruments, none of the documents has focused exclusively on applying sustainable development principles to marine fisheries. The general international standards and practical learning were viewed as equally applicable to the existing legal frameworks for marine governance. Furthermore, the international community has yet to have clear-cut conception of sustainable development. The ultimate consensus goal of sustainable development is to develop and guarantee the survival of human beings and to seek a dynamic balance point between economic development and the eco-environment [

26]. To return to the difficulties relating to marine fisheries, a specific interpretation of marine ecological equilibrium theory essentially connotes sustainable development theory apropos marine fisheries [

27]. Sustainable development theory vis-à-vis aspects of marine fisheries are based on the principle of free access to marine biological resources. This tenet incorporates three aspects [

28]: the fair sharing of oceanic benefits, the equitable use of marine resources, and the harmonious coexistence of human beings and oceans [

29].

The theory of sustainable development also applied relevant international conventions to the marine fisheries industry. The 1946 International Convention on the Regulation of Whaling [

30] focused merely on the sustainable exploitation of specific animals, viz, whales. Notably, further measures were mandated by this convention to ensure the scientific protection of the marine environment and other marine fisheries. However, the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea [

31] attempted for the first time to establish a common legal framework for the exploitation and conservation of marine resources and the protection of the environment. The preamble of this 1982 convention proposed that the state parties would promote the conservation of their living resources and encourage the study, protection, and preservation of the marine environment. Articles 116–120 and Part XII of this convention stipulate the protection of the piscine resources of the high seas and the preservation of the marine environment. These sections deal with the conservation and management of the living resources of the high seas. The two mentioned international conventions do not clearly specify the sustainable development of marine fisheries. Nonetheless, they display a cross-fertilization between the general notions concerning sustainable development and the fisheries regimes by tackling a gamut of issues, including the protection of particular species or the conservation of public marine resources [

32].

The legal concept of sustainable use was first elucidated in the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity [

33]. This convention may be deemed a bid to apply sustainable development theory. The convention outlines its primary objectives as the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of its components, and the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits emanating from utilizing genetic resources [

34]. Biological diversity is defined as the ‘variability among living organisms from all sources including… marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part’ [

35]. This convention does not establish particular obligations relating to marine resources. However, it obliges all states parties to the convention to ‘implement it with respect to the marine environment consistently with the rights and obligations of states under the law of the sea’ [

36]. The Subsidiary Body on Scientific, Technical and Technological Advice posited issues relating to the sustainable exploitation of the oceans and marine resources requiring the attention of state parties, including acidification and deep-sea fishing, marine protected areas, and undersea noise [

32].

In the present Chinese situation, although the Chinese government has not formulated a comprehensive policy or a single law on marine biodiversity [

37], the State Council of the People’ s Republic of China (PRC) instituted the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, the National Marine Functional Zoning Plan, the 13th National Five-Year Plan for Marine Economic Development, and the National Plan for Marine Ecological and Environmental Protection in succession before 2020. The four national instruments offer a general framework and guidelines for marine biodiversity conservation in China. Taking the specific example of marine fisheries, sustainable development essentially embodies the policy idea of a circular economy that requires the exploration and exploitation of marine fisheries based on a harmonious relationship between human beings and the seas [

38]. It also requires minimizing the pollution of the marine ecological environment and the destruction of marine fisheries resources.

On 11 March 2021, the 14th National Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development was enacted [

39]. Under the instruction of this plan, the whole status of the Chinese marine ecological environment is steadily improving, which manifests two aspects related to sustainable development: on the one hand, the overall condition of marine ecosystems has greatly improved, with typical marine ecosystems monitored in a healthy or sub-healthy state; on the other hand, the environmental quality of the main sea-using areas is generally good, and while protecting the marine ecological environment, it also provides firm support and protection for the development of the marine economy.

In addition, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, the Development and Reform Commission, the Ministry of Natural Resources, the Ministry of Transport, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, and the China Marine Police Bureau jointly issued the 14th National Five-Year Plan for Marine Ecological Protection on 17 January 2022 [

40]. This plan can be regarded as the latest guideline for marine biodiversity conservation in China, which provides the following measures:

(1) Improving and perfecting the laws, regulations, and responsibility system for marine ecological and environmental protection, promoting the construction of an ecological and environmental governance system that integrates land and sea, strengthening the marine ecological and environmental regulatory system and regulatory capacity and establishing a sound marine ecological and environmental governance system with clear authority and responsibility, multiparty governance, smooth operation, coordination, and efficiency.

(2) Taking scientific and technological innovation as the driving force and implementing the concept of marine community of destiny, promoting international cooperation in marine ecological and environmental protection, effectively implementing international conventions on marine ecological and environmental protection, and actively participating in global marine ecological and environmental governance.

(3) Clarifying the importance of strengthening organizational leadership and increasing investment protection, strict supervision and assessment, and strengthening publicity and guidance.

It can be seen that the above six national instruments have made a comprehensive plan and specific arrangements for marine biodiversity conservation.

The two principal questions about Chinese marine fisheries from the viewpoint of sustainable development can be summarized as emphasizing the policy and legal aspects of the sustainable development of marine fisheries. The Chinese government and the State Council have taken tangible measures over the last four decades to resolve the two questions from practical and legal perspectives:

(1) How can marine fisheries resources be appropriately utilized?

(2) How can marine fisheries in China be legally protected and managed?

The solutions to the first and the second questions are mainly reflected in the following series of national policies and Chinese domestic laws, respectively [

41].

In addition, the Chinese government has also instituted five policy objectives in order of priority [

7]:

The first and most important policy objective is ensuring the supply of fishery products, including high-quality proteins for human consumption and raw materials for related industries.

The second and third objectives are enriching fishermen’s lives and earning foreign reserves. Development in the marine fishery sector can contribute to fishermen’s income growth; given the comparative advantage of China’s marine fishery sector, it has great export potential, generating foreign reserves for the country.

The fourth objective is protecting the marine environment through sustainable fishing. Overfishing, pollution, and introduced species have had devastating effects on the marine environment. On the other hand, sustainable fishing practices—including constructing artificial ocean reefs, restocking, improving water quality, and other measures—contribute to protecting the marine environment.

The fifth objective is to serve the country’s political and strategic interests. It is recognized that promoting the development of the marine fishery sector will contribute to safeguarding China’s maritime interest in the disputed waters. Furthermore, a distant-water fishing fleet will enable China to expand fishery cooperation with the international community and contribute to China’s international strategy.

Given these, the sustainable development of marine fisheries is not the top priority of the policy objectives but to ensure the supply of fishery products and enrich fishermen’s lives. The last two policy objectives manifest the long-term sustainable development objective based on accomplishing the first and the second. Therefore, the implementation process has no conflict between the above policy objectives.

Policies relating to the legal protection and management of marine fisheries have been successively formulated to denote the sustainable development requirements for marine fisheries by the Chinese legislatures and the State Council as follows:

(1) The fishing license system [

42] refers to fishing license issuance based on the status of marine fisheries resources. The number of fishing licenses issued is determined based on biomass and total allowable catch [

43]. Although this system positively controls marine fisheries operation and production, it neglects to protect marine fisheries resources.

(2) The minimum mesh-size regulation [

44] and the ‘double control system’ [

45] aim at controlling the marine fishing intensity and properly utilizing marine fisheries resources. The two policies provide a chance for China to restore its marine fisheries’ biodiversity and ecosystem.

(3) The implementation of the series of following policies (summer moratorium of marine fishing [

46], the limits on marine fishing vessels and fishing gears [

43], fishery improvement programs [

47], and the establishment of artificial reefs and aquatic germplasm resource protection areas [

45]) aims to better fulfil the goal of the sustainable protection and development of marine fisheries resources.

In addition, the departments administrating fisheries not only promote implementing these policies based on the legal system of Chinese marine fisheries but also have moderately restricted the use of marine fisheries resources to protect economically valuable fishery assets and other organisms by preventing damage to their environment during the fishing process, for example, headed by Zhejiang and Fujian provinces in southern and eastern China, the launched marine nature reserves represent a step toward the sustainable development of marine fisheries. The administrations governing fisheries of the provinces generally controlled fishing methods and limited fishing gear with a focus on protecting juvenile fish and ensuring the capacity to renew marine fisheries resources; they have taken the above policies to gradually recover the ecological environment scientifically [

48]. The positive effects manifest not only the environmental improvement of internal water but also the sustainable development of Chinese marine fisheries and the protection of internal waters by implementing those Chinese domestic laws. Legal efforts to support the sustainable development of Chinese marine fisheries range from implementing the 1982 Marine Environment Protection Law [

49] and the 1986 Fisheries Law [

50] to enacting discrete administrative regulations. Such endeavors evidence a legal relationship between Chinese marine fisheries and their sustainable development.

3. The Development Status of Marine Fisheries Resources in China

Historically, Chinese marine fisheries have evolved from an initial and accelerated phase to the current intermediate and steady stage, revealing China’s dynamic implementation of discrete development and management policies at different growth stages of the industry. This section chooses the period of 2010 to 2020 as the time samples in this research and a selected quantity of catches and aquaculture production, the number of fishers, and the number of vessels involved in the fisheries, which reflect the development status of marine fisheries resources in China. In this section, the first two stages briefly summarize and analyze the statistics of China’s fisheries before 2010, which can be found in the yearbook of Chinese fisheries. Much more attention in the last two stages is focused on analyzing the latest statistics of the recent decade and more.

The initial stage (1949–1978) witnessed two historical events in contemporary China: the establishment of the PRC and the launch of reforms accompanied by the adoption of the opening-up policy. The Chinese government also began to attach great importance to exploiting marine resources via fisheries to aid post-war reconstruction and drive economic growth [

51]. Although the fishing and loading methods were crude and outdated in this period, the development of internal water fisheries initially characterized the government-leading model, which largely facilitated fisheries production development and greatly satisfied the Chinese society’s demand for material wealth. The total production of fisheries increased from 524,000 tons in the early years of the Republic of China to 3,489,000 tons by the end of the First Five-Year Plan [

52]. However, the use of marine resources for fisheries developed slowly between the First Five-Year Plan to the eve of China’s adoption of reforms and opening up because of various political campaigns. The aggregate production of Chinese fisheries was maintained at around 3 million tons, and the fisheries industry stagnated or even experienced a decline in that period [

53].

The accelerated stage (1978–2000) witnessed the institution of the above policies and laws oriented primarily toward facilitating the exploitation of fisheries resources and ensuring the growth of the marine economy [

54]. Meanwhile, the Chinese governments at all administrative levels offered financial support to local fishing communities and companies to expand their marine fisheries activities [

11]. Fishing capacities increased rapidly with such measures, propelled by the massive influx of new fishing personnel and a new wave of shipbuilding [

55]. The fishery licensing system and registration system were also established to comply with the requirements of the times, which not only regulate the market of marine fisheries but also promote the smooth development of Chinese fisheries. Between 1979 and 1999, the number of full-time and part-time fishers was augmented by one million and 440,000, respectively. The number of motorized marine fishing vessels increased by 53.37% at this stage, while the annual catch escalated by 35.74% [

56]. Thus, Chinese marine fisheries witnessed an immense increase in catches and production, which was achieved through the overutilization of China’s marine resources [

7]. This stage of practice reveals that an increasing number of fishing boats and fishing professionals exploited marine fisheries resources at this juncture and reflects that the methods used by marine fisheries to exploit resources gradually evolved during this period from traditional fishing to new types of fish farming. Unfortunately, the backward technology of marine fisheries and unrestricted fishing caused a significant decrease in Chinese fishery resources.

Chinese marine fisheries entered an intermediate stage after 2001. The Chinese government has signed increasing numbers of bilateral fisheries agreements with its neighboring nations [

57], which forced domestic fisheries management to be changed, resulting from conforming to the basic requirements of these bilateral agreements and exploring the possibility of further cooperation with these nations on marine fisheries. Under this circumstance, the relevant domestic laws concerning the protection and management of marine fisheries have been revised in succession. The consequence of the changes was further increasing the pressures on coastal fishing from legal and management perspectives, which reflects how to solve the contradiction between development and environmental protection to achieve sustained and steady economic growth.

In this context, the Chinese government had also to reconsider the trade-offs between socio-economic and conservation goals [

58]. Later in 2006, the Chinese government first asserted the goal of managing marine fisheries in the ‘Program of Action on the Conservation of Living Aquatic Resources of China’ [

59]. This document demonstrates the Chinese government’s efforts to find a balance between economic development and ecological sustainability concerning marine fisheries. The Chinese development philosophy has also gradually shifted under this program from emphasizing economic growth to prioritizing ecological conservation, steadily advancing the reform process. Resource conservation has thus become a priority for managing marine fisheries in China [

56]. Consequently, a series of amending laws and policies supporting reforms in national fisheries have been enacted and promulgated in succession.

The following section discloses conclusions about the steady stage from data derived from qualitative research methods and subjected to statistical data analyses (2010–2021).

The annual catch output represented the primary barometer for measuring China’s success in developing marine fisheries and for assessing the performance of the government departments charged with fisheries-related matters [

60]. Statistically, the total output of marine fisheries increased from 0.6 million tons in 1950 [

61] to 1314.78 million tons in 2015 [

62]. The catch output during this period depended principally on increasing fishing efforts to manage resources for marine fisheries [

45]. However, a progressive decrease has been observed in the total marine fisheries output since 2015. By 2020, this number had dropped to 947.41 million tons [

63]. In terms of distant-water fisheries catches, and freshwater catches, the distant-water fisheries catches have shown a general fluctuating trend since 2013. However, the development of distant-water fishing was a practical approach emphasized by the Chinese government to address domestic demands, mitigate the supply imbalance of fishery products, and provide work for fishers [

7]. Freshwater catches have also presented a decreasing trend since 2017 [

63]. It should be pointed out that the development of distant-water and freshwater fisheries inevitability involves the issues of the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf. However, China enacted its Law on the Exclusive Economic Zone and the Continental Shelf (EEZ/Continental Shelf Law) in 1998 after it had ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea in 1996 [

64]. By so doing, the Chinese government has formally established a legal regime for its exclusive economic zone and continental shelf. The development of distant water and freshwater fisheries benefited from this legal regime. Nevertheless, China has much to do in implementing the EEZ/Continental Shelf Law at the domestic and regional levels. At the domestic level, given that the EEZ/Continental Shelf Law is a legi generali, it needs a set of detailed administrative regulations (lex specialis) for its implementation.

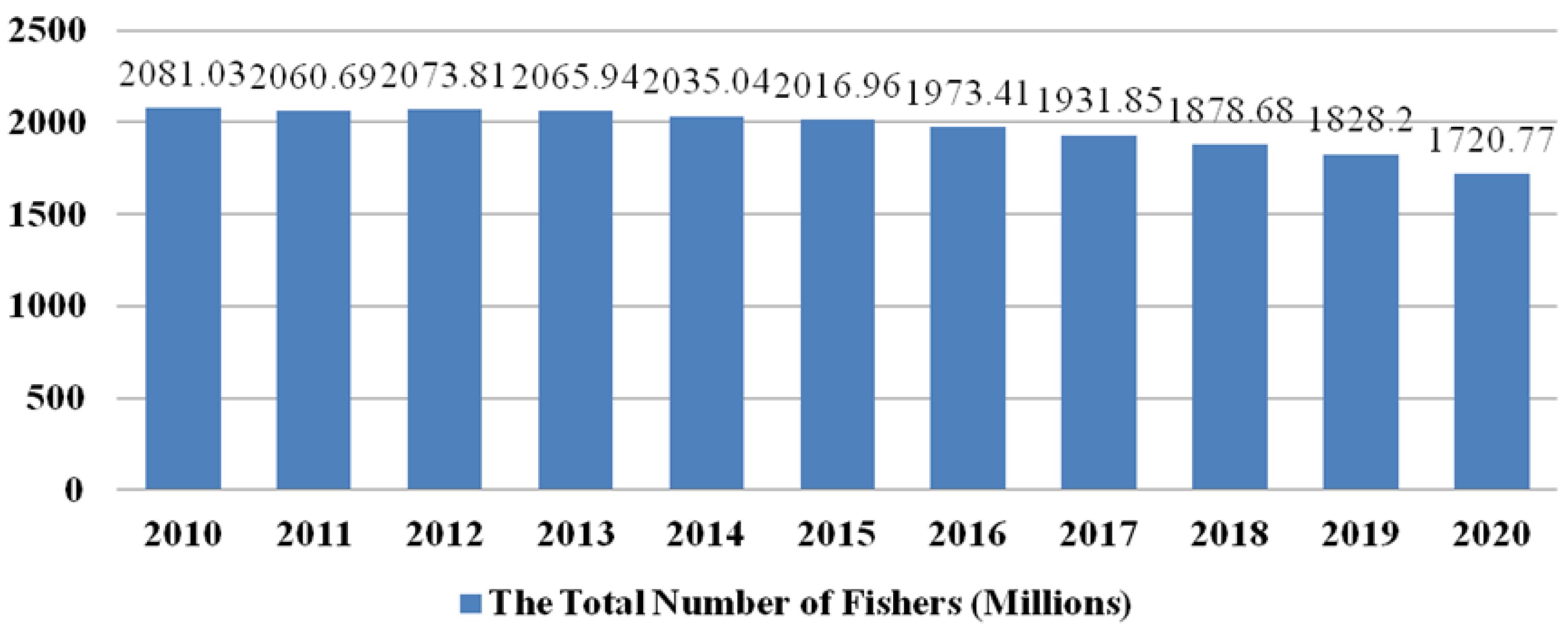

Although the following catches were steady for the 11 years reported but fluctuated and presented a decreasing trend in catches in Chinese waters, the essential facts and data materials illustrated in

Figure 1 demonstrate the almost decade-long recession in China’s fishing output. Complicated policy and management aspects and the law have caused such a situation. These factors have exerted both positive and negative effects. First, the decline of marine fisheries resources has comprehensively illustrated that overfishing and misuse of marine resources, coastal land reclamation, and industrial pollution have, over time, restricted the development of China’s fisheries sector. The sustainability of marine fisheries cannot be guaranteed. Second, the increasing demands for marine fisheries resources and the deterioration of the ecological environment make sustainable fisheries development complex and challenging despite China’s implementation of policy reforms for the management and development of fisheries.

From the perspective of fishery production, the annual Chinese fisheries production includes the output of both freshwater and mariculture fisheries. The rapid expansion of the output of fisheries, which now contributes almost three-quarters of China’s total marine production, has also ranked topmost for over 30 consecutive years [

65]. This achievement not only benefits from the support of the above policies and laws but also relies on the fact that every province has strengthened its capacities for disaster prevention and mitigation and has improved the cultivation of fish farming. Mariculture production has increased from 0.15 million tons in 1954 [

66] to 2065.33 million tons in 2019, maintaining constant growth [

67]. However, the recent pandemic, habitat destruction, resource use conflicts, and biodiversity decline caused the total output of fisheries to decline in 2020. Although the freshwater fisheries production of 2020 also decreased slightly vis-à-vis 2019, the main development trend remained smooth (

Figure 2) [

63].

Marine fisheries represent the magnitude of the sector in China in terms of numerical values. Millions of fishers have lived and worked along China’s coasts for several generations. The total number of fishers increased gradually but annually before 2010 [

68], demonstrating that practical demands for the exploitation and utilization of marine fisheries resulted in the growth of fishers. The income differences between fishers and farmers attracted peasant workers from China’s inland provinces to join the marine fisheries in increasing numbers [

7]. Marine fisheries resources are renewable; nonetheless, they have been highly exploited and utilized at or close to their maximum sustainable limits: marine resources for fisheries are depleting despite being renewable [

69]. Thus, an irreconcilable contradiction exists between the demands for the exploitation and utilization of marine resources for fisheries and their sustainable development.

Additionally, the rising costs and the changing fisheries management policies have significantly affected the livelihoods of the traditional fishers in China. Some fishers have abandoned their generational occupations and have had to move away from their homes, change jobs, and work for tour operators or the service industry. Therefore, the total number of fishers decreased from 2012 to 2020 (

Figure 3) [

63].

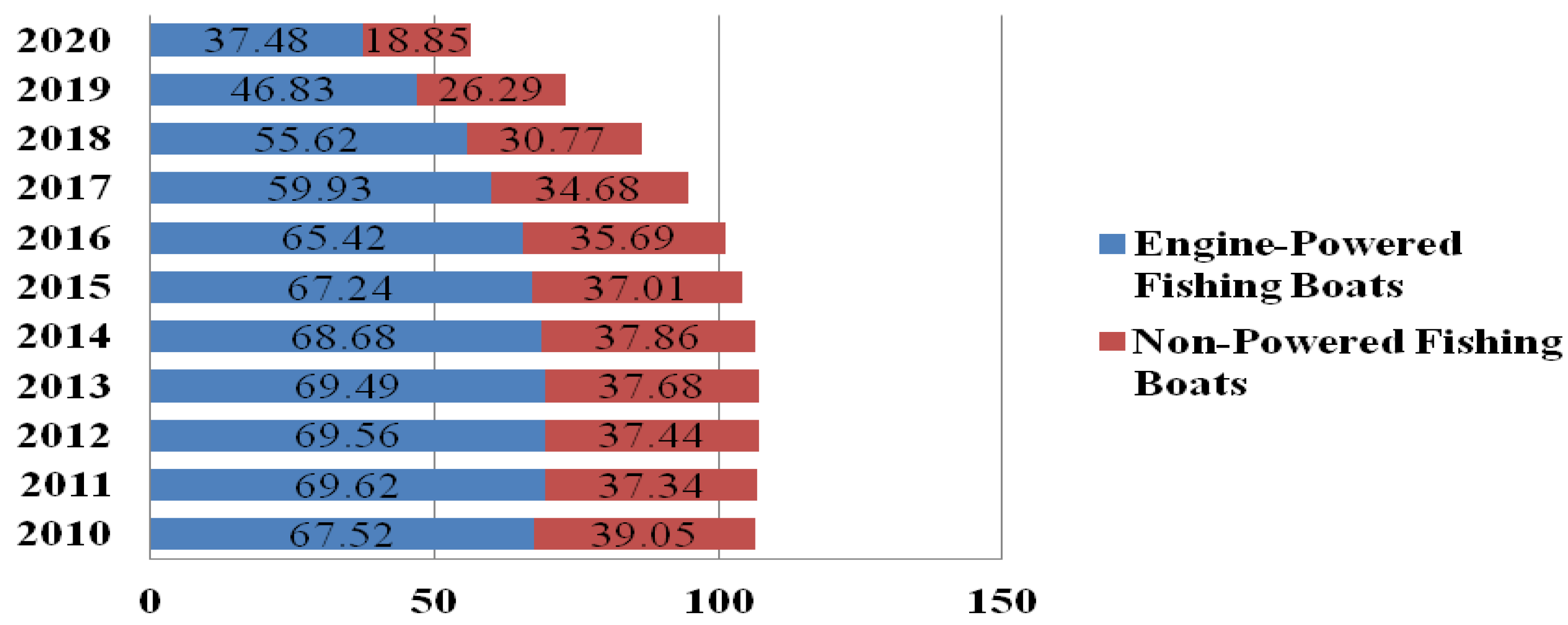

The data presented in

Figure 4 exhibit the year-on-year changes in the number of Chinese fishing vessels, which reflects that the aggregate of fishing vessels (engine-powered and non-powered fishing boats) has also declined over the last seven years (2014–2020) [

63].

The root cause of a slight annual decrease in engine-powered and non-powered fishing boats lies in the adjustment of national tax policy. Since introducing the reduction and transfer of tax policy in 2006, China decided to abolish the agricultural tax and started subsidizing agricultural production; as a sub-sector, marine fisheries receive financial support through a fishing fuel subsidy. Parallel to the phenomenal increase in China’s agricultural subsidy during the same period, the fishing fuel subsidy increased yearly [

70]. Meanwhile, the Chinese government not only encourages the downsizing of engine-powered and non-powered fishing boats but also offers much more subsidies to every ship downsized. In contrast, under the fishing fuel subsidy, fishermen will merely receive less than RMB 1500 per kilowatt per year in some areas [

71]. If a fishing boat owner participates in the government ship-reduction program, he/she can get only two years of the fishing fuel subsidy [

70]. Given this, although the fishing fleet’s average size and horsepower improved significantly, the number of the two types of fishing boats has been decreasing because of conflicting fishing subsidies provided by the government [

7]. Additionally, the number of engine-powered fishing boats still significantly exceeds that of non-powered fishing boats. This situation directly reflects the implementation of marine fisheries management. The utilization rates for engine-powered fishing boats are higher than for non-powered fishing boats because the former is propelled by high-powered diesel engines and includes electronic equipment for navigation and detecting fish schools. The utilization of different fishing vessels can also reflect the fishing output. Overall, the Chinese government achieves the quantitative target of reducing the total number of fishing vessels [

72] and indirectly reveals the diminishing marine fisheries resources by implementing zero and negative growth policies and strategies targeting double control [

73].

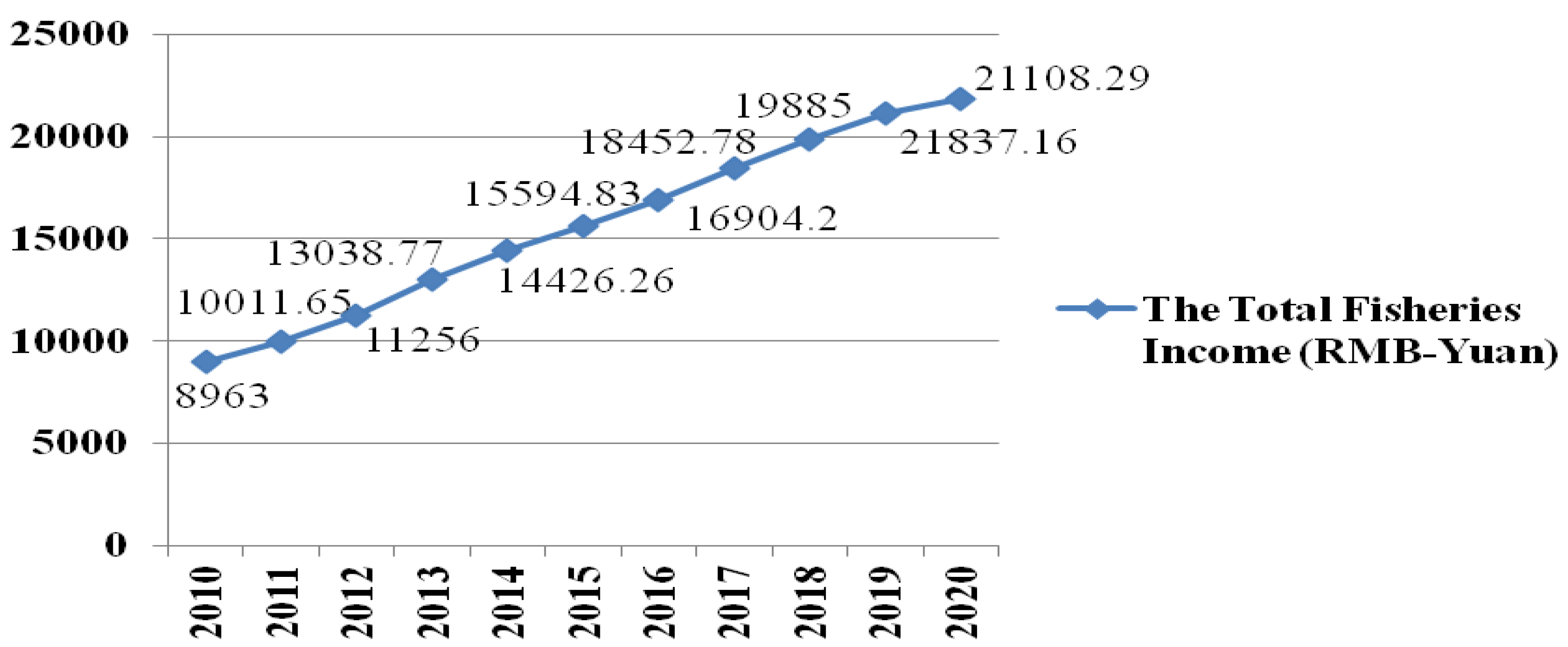

The marine fishing industry is critical for economic development, income generation, and employment in the coastal areas of China. Traditional generational fishers are extremely dependent on income from fisheries [

74] (

Figure 5). Incomes from fisheries rose rapidly in 2012 after the industry breached the RMB 10,000 mark in 2011 (

Figure 5) [

75]. Survey data projected fishers in coastal provinces and disclosed the obvious income gap between coastal and inland regions. This income difference has attracted an increasing number of regular farmers from the inland provinces to join the fishing industry along the coast. Notably, the proportions of income in fishing households also show a rising trend through the increasing efforts of varied national policies introduced to benefit fishers.

5. Legal Issues on the Sustainable Development of Marine Fisheries

As previously mentioned, apropos legal regimes governing marine fisheries, the legal system has essentially accomplished the historical task of ‘ruling fisheries by law’. Nonetheless, a particular gap exists between achieving the sustainable goal of ‘promoting fisheries by law’ and ‘protecting fisheries by law’. China finds itself at a crossroads, as is graphically illuminated by the legislative developments vis-à-vis the protection of marine fisheries. Generally speaking, legal issues on the sustainable development of Chinese marine fisheries primarily comprise three types of issues:

(1) Those related to law-making,

(2) Those associated with law enforcement and administration,

(3) Those vested in legal liability.

5.1. Issues in the Law-Making

It is posited that the current legal system regulating marine fisheries may be compared to an airplane with two wings: the Marine Environment Protection Law and the Fisheries Law. A series of administrative regulations and measures to improve the management of marine fisheries resources constitutes the fuselage. This airplane may appear sturdy, but the comprehensive legislation on the protection and development of Chinese marine fisheries lacks integral planning and encompasses numerous legal blanks.

First, the Marine Environment Protection Law and the Fisheries Law evince discrete emphases and weaknesses. The former lays particular stress on the prohibitive stipulations apropos the impact of human activities on the marine environment rather than the general provision of resources for marine fisheries. The Fisheries Law also deals with issues concerning marine fisheries; however, this law cannot tackle the increasing changes in the varied aspects of fisheries. The Marine Environment Protection Law has also not achieved the objective of establishing a legal connection with the Fisheries Law, precluding the appropriate construction of a scientific and legal framework for the protection and development of Chinese marine fisheries. The Marine Environment Protection Law does not incorporate relevant provisions about marine fisheries’ resource utilization. For example, Article 20 of Chapter 3 of the Marine Environment Protection Law (Amendment 2017) stipulates the protection of endangered marine organisms as an essential aspect of conserving the resources of marine fisheries. However, it does not mention the protection of marine fisheries. In addition, fishing operations are quite harmful to the marine ecological environment. Article 28 of this law merely provides for mariculture rather than the entire fishing industry [

91]. It is thus evident that the two existing laws lack the necessary internal relevance and logic.

Furthermore, the legislative purpose and the basic principles of the current Fisheries Law need to clearly articulate provisions pertaining to the principles of sustainable development. This situation does not match the Marine Environment Protection Law and does not help China’s quest for the sustainable development of marine fisheries [

92]. Given the current circumstances, the relationships between general and special laws also cannot be reflected in the legal relationship between the Marine Environment Protection Law and the Fisheries Law.

Second, the independent legal status of marine fisheries is far from being realized in China. Marine fisheries are a distinct category, and differences are mandated in their protection approaches, sustainable development orientations, operational procedures, and standards. However, the legal norms governing Chinese marine fisheries encompass the legal framework regulating all fisheries. The enactment of most Chinese laws on marine fisheries is based on the agricultural perspective rather than special consideration of marine fisheries management [

69]. Additionally, most legal norms regulating marine fisheries are selected and integrated from existing domestic laws and thus exhibit piecemeal legislative characteristics [

1]. Such circumstances expose the necessity of contemplating an independent legal status for marine fisheries rather than providing general provisions for this industry within the ambit of the Fisheries Law and other regulations.

Third, the Fisheries Law and Detailed Rules constitute the most relevant legal provisions concerning marine fisheries and cannot be ignored. These instruments have been revised numerous times but continue to encompass substantial difficulties. The Detailed Rules merely offer precise definitions of terms such as ‘internal waters’, ‘all other seas under the jurisdiction of China’, and ‘fisheries waters’ [

93]. The Detailed Rules do not specifically define ‘fishery resources’, ‘offshore waters’, and ‘distant waters’, hampering the conceptual clarity of legislation pertaining to the sustainable development of marine fisheries. The current status of resource utilization by China’s fisheries is to gradually increase the scale of offshore mariculture and encourage the development of distant-water fishing. The Fisheries Law introduces the concept of offshore fishing, and the Detailed Rules advance the concepts of offshore water and open-sea fish farms. In this context, offshore and distant waters should be scientifically defined to enable the Fisheries Law and the Detailed Rules to function more effectively.

5.2. Issues in Law Enforcement and Administrative Management

Examining the legal framework governing Chinese marine fisheries and the state of the relevant fisheries resources in China provides evidence that the Chinese government has elevated the legal status of marine fisheries through various legislative actions. However, enforcing Chinese marine fisheries laws entails a decentralized and fragmentary administrative system. Such dispersion further generates law enforcement and management problems relating to China’s legal system and administrative efficacy. The Chinese government has consistently strengthened law enforcement and management to enhance the protection of marine fisheries. In practical terms, however, China’s marine fisheries are not effectively protected or sustainably developed.

The issue of administrative law enforcement power over China’s marine fisheries is most responsible for the deficiencies mentioned above. Article 3 of the Fisheries Law states that fishery supervision and administration shall be subject to unified leadership and graded administration by the state. However, Articles 6, 7, and 8 of the Fisheries Law allocate law enforcement authority. It is self-evident that fishing activities on inland waters should be monitored and directed according to their administrative divisions by fisheries departments at regional governments at or above the county level. Fisheries-related administrative departments, inspection offices for marine fisheries, and supervisory institutions connected with the fisheries administration can exercise law enforcement powers vis-à-vis the management of marine fisheries resources. Nevertheless, the boundaries between authority and mutual legal responsibility remain indeterminate, and the practical enforcement process is multi-departmental and is not effectively conducive to execution.

Conversely, situations may arise when multiple departments could shift the responsibility of law enforcement to each other, which would also not be conducive to the sustainable development of marine fisheries. In practice, the lack of a holistic perspective and planning leads to poor coordination between administrative departments at all levels. Hence, management is difficult and ineffective because it is uninformed. The excessive decentralization of the authority and responsibility of administrative departments has significantly weakened law enforcement pertaining to fisheries. For example, there are no clear and unified provisions on procedures for issuing fishing licenses.

Second, the management of marine fisheries is currently based on a management hierarchy encompassing the Fishery Administration of the Ministry of Agriculture, local marine fisheries authorities, and the State Oceanic Administration [

94]. This structure is beneficial because it allows the existing administrative platform and administrative means to be fully utilized to guide and manage the marine fishing industry. However, the marine fisheries industry is market-based. While the existing administrative hierarchy can adequately achieve the macro-level regulation of fisheries (meaning the extensive and holistic measures of fishery regulation, which focuses on policies and institutions of general application significance), it is less effective in adopting micro-level governance pathways (the legislation, law enforcement, and monitoring mechanisms). Specifically, the inadequate monitoring mechanisms for marine fisheries reflect driving benefits, supervision and management inadequacies, and the poor enforcement of laws. For example, heavy fishing remains prohibited despite amendments to the Fisheries Law and the introduction of regulations on fishing practices. That the existing fisheries management mechanism does not consider private fishers and their legitimate interests is a primary reason affecting the rational exploitation of fisheries resources. In addition, Article 22 of the Fisheries Law states that the state should determine the total fishable amount of the fishery resources and implement a fishing quota system using the principle that fishing quantities should be lower than the increasing quantum of fishery resources. Unfortunately, the implementation of this principle shows the disadvantages of being too rigid. The strict enforcement of seasonal fishing embargoes only temporarily mitigates the deterioration of fishery resources and can lead to a surge in fishing efforts after the closure period [

1].

Third, the disparities in the grass-roots law enforcement of marine fisheries pose various problems. The grass-roots law enforcement endeavors about marine fisheries are funded by local governments, whose financial situations and the importance they attach to marine fisheries resources determine the funding available for enforcement. Areas displaying poor economic conditions and regions that do not attach importance to the protection of marine fishery resources would allocate less funding and thus contribute directly to the ineffectiveness of resource management for local fisheries. Besides, the shortage of professional and technical staff and backward law enforcement equipment also currently weaken the safeguarding and law enforcement mechanisms necessary for the sustainable development of marine fisheries.

5.3. Issues of Legal Liability

The penalty provisions outlined in the chapter on legal liability in the Fisheries Law are listed from Article 38 to Article 49. These articles focus primarily on violations of the fisheries management system and provide penalties for the use of illegal fishing methods and fishing during periods banning fishing or designating areas closed to fishing. The Detailed Rule also stipulates specific penalty provisions for the implementation of the Fisheries Law. The following issues concerning legal liability persist despite these provisions.

First, the provisions do not stipulate the legal responsibility of the marine ecological environment and pollution accidents caused by marine fisheries, which are to be pursued under the Marine Environment Protection Law. This case is typical and not isolated: the provisions of legal liability and legal penalty are scattered under different laws. That legislative acts concerning marine fisheries do not adequately tackle the legal liability of marine fisheries is further illustrated.

Second, the current types of administrative penalties stipulated are quite simplistic. Corresponding legal liability is specified for restrictive and prohibitive provisions. On the contrary, legal regulations should supervise the entire process of fishing operations and auxiliary fishing activities. There are no corresponding penalties in the present law for all fishing-related ‘three-nothing’ (no ship name and ship number, no ship certificate, no port of registry) vessels. This situation should attract enough attention and must be resolved in an amendment to the Fisheries Law.

Third, the fines and penalties stipulated for the current stage do not correspond with the growing levels of socio-economic development. Hence, fines must be appropriately increased.

6. Possible Approaches to the Sustainable Development of Chinese Marine Fisheries

The above illustration and analysis of the legal issues vis-à-vis the sustainable development of Chinese marine fisheries allow the recommendation of enhancing the legal protection mechanisms of marine fisheries resources as follows:

Chinese lawmakers can take a two-step approach to adopt a gradual legal reform scheme because of the current decline of marine fisheries resources and the illegal development of the marine fisheries industry.

The first step would entail the enhancement of the legislative standards and the improvement of the interface between the current domestic laws and regulations before satisfying the conditions of mature legislation. Significantly, both the Marine Environment Protection Law and the Fisheries Law are essential to the sustainable development of Chinese marine fisheries, which will determine the sustainable development of the marine fishing industry. The Marine Environment Protection Law is required to elucidate the concept of marine fishing; however, it should also add a chapter focusing on the protection of marine fisheries. The Fisheries Law should remain consistent with the Environmental Protection Law and the Marine Environmental Protection Law. The legislative purpose of the Fisheries Law includes promoting the sustainable development of marine fisheries resources, and the basic principles of sustainable development of marine fisheries resources should be established in the general section of the Fisheries Law. However, the legal principles are generally not directly applicable. It is necessary to introduce sustainable development for the legislative purpose and establish sustainable development principles for future legal provisions relating to marine fisheries resources. If possible, lawmakers could consider instituting a chapter to regulate marine fishing, allowing the specific and concrete implementation of marine resource management suited to the current contexts of marine fishing. Furthermore, integrating the legal regulations relating to the exploitation of fisheries resources into the Fisheries Law would make it easier for the administrative authorities to enforce the Fisheries Law, facilitating the sustainable development of marine fisheries resources.

In the second step, the imperfections in the legal system would directly affect the enforcement framework. The lack of comprehensive regulation of the protection of marine fisheries resources would inevitably lead to the imposition of stop-gap measures. It is thus necessary to offer a unified regulation by introducing a law on the protection of marine fishery resources based on the consolidation of existing legal norms established for marine fishery resources. Both ideas and approaches can apply to the legislative design of the Marine Fishing Law.

The strengthening of law enforcement efforts to develop and manage marine fisheries cannot be overemphasized from the perspective of law enforcement. The sustainable development and management of marine fisheries should be adapted in practice to the Chinese situation and should not simply be centralized or decentralized. Specifically, the solution to problems confronting law enforcement of marine fisheries may be reforming administrative institutions. Lawmakers could initially consider the institution of an integrated law enforcement department in the Fisheries Law. For instance, a unified law enforcement department could exercise the powers and functions of different administrative departments. Such an authority can stop and punish policy or regulation violations in the name of a particular administrative department. In addition, the established unified law enforcement department can effectively integrate fisheries management, fishing port supervision, fishing vessel inspection, and even administrative powers related to protection and sustainable development according to local requirements. Hence, administrative powers can be exercised more systematically, scientifically, and efficiently, precluding conflicts emanating from overlapping law enforcement powers and becoming more conducive to the sustainable development of Chinese marine fisheries resources.

Additionally, a joint law-enforcement mechanism can be gradually inserted into the Fisheries Law from the aspect of the institutional system. The joint enforcement approach can effectively integrate the varied resources of administrative enforcement, facilitate the coordination of the enforcement relationship between various administrative organs, and improve enforcement efficiency. Joint law enforcement does not involve the transfer of administrative powers and does not entail the interests of diverse administrative organs, making it more operable in reality.

From the perspective of the safeguarding mechanism, the sustainable development of marine fisheries resources cannot be achieved without sufficient funds, professional and technical personnel, and technical equipment. Therefore, establishing a safeguarding mechanism for marine fishery resources is crucial for sustainable development.

Legal measures may be adopted as follows: first, the central government should legislate to allocate special funds to the marine fisheries authorities in coastal areas. In addition, central and local finances could jointly support and encourage the local research and development of technologies to sustain marine fisheries resources. Second, legislation should designate local funds for the sustainable development of marine fisheries resources, which regional financial allocations may bolster. Local governments could offer funds to support the sustainable development of marine fisheries resources and include funds for the sustainable development of marine fisheries resources in their budgets. Third, the current Fisheries Law could establish a safeguard mechanism for marine fisheries resources and build supporting scientific research institutions and laboratories.

Legal liability provisions are essential for the sustainable development of marine fisheries resources. Legal liability denotes the use of punishment to regulate the behaviors of fishers, enterprises, and administrative and enforcement personnel. Punishment is not an end in itself, but it is necessary to guide marine developers and managers to promote the sustainable development of marine fisheries.

The legal responsibilities of fishers and enterprises should be further clarified in a future amendment to the Fisheries Law. Different subjects could be assigned discrete legal responsibilities according to different roles, acts, and aftermaths.

The fishing-related ‘three-nothing’ vessels should be confiscated. These vessels could also be dismantled on the spot, blocking their access to the production process.

The legal lag is embedded in the flaws of the current laws. The types of administrative penalties should also increase, and the punishments for transgressing marine fisheries should be amplified. Fines should be raised, and penalties should increase with socio-economic development.