Abstract

As globalization is facing increasing challenges, regionalization demonstrates the potential to effectively address many transboundary issues. Current international fisheries management has attracted criticisms, among which the poor incentives for countries to attend and comply with the rules are notable. This paper aims to explore whether the incorporation of fisheries policies into regional economic blocs can be a solution to improve cross-border fisheries management. The development, problems, and future of the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) of the European Union are explored in detail. This paper concludes that the evolution and implementation of the CFP provide some precious lessons for the world. An appropriately designed regional fisheries scheme would help to create incentives for countries to participate in regional regimes and improve their fisheries management. Economic incentives, a good institutional design, and financial and scientific support are critical factors in favor of adopting common fisheries policies under regional economic frameworks.

1. Introduction

The world is undergoing profound changes. Globalization that has deeply influenced individuals, societies, and the international community is facing increasing challenges and antipathy [1]. Regionalization is characterized by fewer members, closer interaction and connections, and better economic and political security guarantees, which make it easier for States to find common interests. Great potential can be identified to develop regional multilateral approaches, especially with the rise of Asia and the development of less-developed regions [2]. Fisheries issues have been an important topic in international society as they involve environmental, economic, political, and social factors. They also concern biodiversity and ocean sustainability. The economic performance of many coastal countries is in relation to the fisheries industry and the global seafood trade has been lively. It is also a highly sensitive political issue when delimitation of waters and geopolitical factors are involved. In addition, fisheries are also of high social significance as it is directly related to the livelihood of fishers and food supply. Fisheries management needs international cooperation and effective implementation of the related agreements.

Current fisheries management is still fundamentally based on national willingness, ability, and implementation. A dual system has been adopted by the law of the sea: waters within the EEZs are subject to the management and jurisdiction of the coastal States, and high seas are subject to the principle of fishing freedom (although there has been a trend of imposing more restrictions and obligations on States) and joint management. At the international level, the UN (including the FAO) has provided a series of frameworks, principles, regimes, and guidelines to promote the conservation of living resources in the ocean. At the regional level, regional fisheries bodies (RFB), especially regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs), are playing significant roles in improving cross-border fisheries management. They are organizations dedicated to fisheries management and play a special role in providing data and advice, making decisions based on scientific assessment, and monitoring in-time changes and implementation. The key problem, however, lies in the incentives of States to participate in and effectively implement the international and regional management schemes [3].

Given the potential of future regionalization and the challenges faced by the current international fisheries management regimes, this paper starts from an idea of whether regional blocs can help to improve the incentives for States to attend and effectively implement cross-border fisheries management. The EU, which has been so far the most successful regionally integrated economy and adopted a Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) at the union level, is taken as an example to examine in detail how and how well it works for adopting fisheries policies within regional economic frameworks. By examining the evolution, problems, and effect of the CFP, this paper provides insight into the EU experience and its possible future. Lastly, an assessment is given, providing an analysis of possible implementation in other regions of the world and lessons that can be learned. The EU is motivated by specific situations (security needs after the wars, benefit of economic integration, wide political, social, and cultural similarities) and requires a radical transformation and centralization of powers [4]. Therefore, it is doubted whether the EU experience can be duplicated by other regions (Africa has been following the EU experience of integration but has had much less success [5]). However, it can still provide some precious lessons. The EU experience has suggested the importance of the linkage of fisheries issues and other economic issues, which creates higher incentives for States to take part in regional management. It also demonstrates the significance of good institutional design, involvement of science, and effective enforcement and monitoring.

2. Background

2.1. From Globalization to Regionalization?

This round of globalization, in some scholars’ view, capitalist globalization [6], characterized by inclusion and integration of markets, liberalization and deregulation, growth of transnational corporations, and international division of labor, has been going on for decades [7]. The debate concerning the future of globalization has been fueled especially since the 2000s [8,9]. The 2008 financial crisis happened in the US, which is the world-leading economy and biggest beneficiary of globalization and became a significant event [10]. The world has witnessed an increasingly clear trend of “anti-globalization” since then. The European debt crisis, the following failed European Constitution referendums, and Brexit (failure in regional political agenda), the trade war against China started by the US (market barriers and restrictions on trade), and the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic since 2019 (border control and social isolation) have all significantly contributed to the trend of deglobalization. Scholars from different fields have provided reflections, criticism, and alternatives to globalization. Most of the criticism concentrates on periodical economic crises which may have a worldwide effect, increasing inequality among different countries and different groups of people, unemployment or limited and customized job vacancies in one market, environmental problems, especially in less-developed countries, and the possible increase in social instability [7,11,12]. In particular, with worsened US–China relations and the physical difficulties caused by the pandemic, the fragility of global supply chains has been exposed [13,14]. Academic circles have made efforts to find alternatives or adjusted approaches to globalization for years and regionalization is one of the proposals.

Compared with globalization, regionalization has its own advantages: there is more interaction among countries in the same region and it is easier for individual countries to find common interests [15]. In this regard, regional frameworks are facing fewer difficulties to be developed and guaranteed. Regionalization is not new yet has attracted special attention recently. Some empirical findings have demonstrated the fast development of regional cycles and regional frameworks [16,17]. Similar to globalization, regionalization is a multilateral solution under the current sovereign state-based international governance. Regionalization experienced ups and downs. Söderbaum (2016) identified two waves of regionalization as the “old” and “new” regionalization [18]. After the end of World War II, many regions enjoyed a wave of regionalization under the newly established world order. The primary incentives behind it were protectionist trading schemes and security concerns. He further notes, that from the 1980s, a new wave of regionalization can be identified, which features a “state-led” style instead of natural society integration. Regionalization, driven by technology and transportation development, economic liberalization, and the pursuit of efficiency [19], and the demand for cooperative management of transboundary issues have again faced increasing challenges in the last two decades. The EU experienced significant difficulties pushing further political integration after its enlargement. Regionalization in African, Latin American, East Asian, and Arab countries can hardly be regarded as “successful” as effective regional schemes are insufficient. An eye-catching regional integration was ASEAN, which explored a softer and more flexible style of regionalization compared with the EU [20].

Today, the world confronts complex problems and challenges. One possible reason leading to anti-globalization is the unbalanced movement speed of capital, goods, and humans. Put differently, the social and cultural interactions among States did not keep pace with the removal of market barriers [1]. As the old-style globalization gained widespread criticism, regionalization seemed more attractive. Firstly, technology development and economic efficiency are still encouraging economic integration in the world. Increased cross-border interaction is especially based on the development of communicating technologies, transportation, and other infrastructure. Market integration can improve economic efficiency and unlock regional potential. In the long run, the world has gone through and will continue to experience integration with technology development. Secondly, as the world order is undergoing instability and changes, States have a higher self-protection demand. The pandemic not only exposed the danger of long and widely distributed supply chains but also further triggered nationalism all over the world [13]. Protectionism may revive. However, with decades of globalization, this time, protectionism may not limit its scope strictly within national borders but rather be influenced by regional market integration and political recognition among neighboring countries. Core States may lead to regionalization and develop a regional supply and distribution chain which better fits their national security interest. Thirdly, the regional integration of less-developed countries deserves special attention. The liberal international order established and dominated by Western countries is being damaged. The decline and inability of international organizations such as the World Trade Organization (WTO) is a good example. The once attractive internationalism is facing serious challenges. In contrast, regionalization in some less-developed regions has demonstrated its potential. After several years of failed, rushed, or unsuitable regional regimes in regions such as Africa and Latin America, new progress is expected to be made. For example, in the Asia-Pacific area, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP, regional trade bloc concentrating on the removal of market barriers) was concluded, demonstrating the will of the signatory parties to promote regional cooperation. In Africa, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) was founded in 2018, and trading under the agreement commenced in January 2021.

In summary, the world has witnessed increasing challenges to globalization. However, there are still strong incentives for integration and demand for multilateral cooperation. Regionalization has great potential especially in less-developed regions (as technological and infrastructure developments in these regions can make a big difference). The discussion of the issues that need cross-border cooperation and coordination should take this trend into consideration to explore better and more effective solutions.

2.2. Status Quo of the Global Fisheries Management

Fisheries is one of the areas with a special demand for cross-border cooperation. Marine life is moving and sharing the same oceans regardless of boundary delimitation by humans. Fish are common-pool resources that may lead to over-exploitation of coastal States (the tragedy of the commons) and insufficient management (the free-rider problem) [21,22]. Particularly, with the development of vessels, fishing facilities, and skills, illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing has become a critical issue faced by the international community. Cooperation and institutional guarantee are therefore needed. Various legal instruments have been employed by the international society concerning fisheries management. International agreements can be divided into two categories: hard law and soft law. Treaties signed and ratified by States are legally binding and States are responsible for the breach of them. Soft law, such as guidelines, declarations, plans, etc., has no legally binding force. States can voluntarily follow the norms to promote their practice and reputation.

The United Nations (UN) has established a regime mainly based on two treaties to protect fish stocks. Some principles and general provisions are provided by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), a fundamental legal framework concerning maritime issues, especially Articles 61–68, 116–120, 197 of the Convention. A distinction between the EEZ and high seas is adopted. Within the EEZ, the coastal States have exclusive rights and jurisdiction concerning fisheries issues. On the high seas, freedom is respected. States have the obligation to cooperate and take measures to conserve living resources (however, UNCLOS provides neither additional binding standards for measuring the outcomes nor monitoring mechanisms, and therefore, the implementation of this general provision basically depends on the signatory parties). The 1995 United Nations Fish Stock Agreement (UNFSA) provides a further legal framework for cooperative management of straddling and highly migratory fish stocks. It is directly linked to UNCLOS but has different signatory members (168 parties have ratified UNCLOS and 91 parties have signed the UNFSA [23]). States are subject to obligations to adopt a precautionary approach and cooperate either directly or through subregional or regional organizations (similar to UNCLOS, it also fails to provide measurable standards for the implementation). The UN legal frameworks, although providing mostly general provisions, laid the foundation for international fisheries management.

The FAO, as a specialized organization, provides more complete and practical regimes. Its main functions are described as “to provide a forum for the development of norms” and to collect, analyze, and disseminate data and information. The FAO has developed several instruments, both legally binding treaties and non-legally binding “soft” instruments. Treaties include the Compliance Agreement (concentrating on duties of the flag States, more than 40 signatory parties) and the Agreement on Port State Measures (70 signatory parties). Soft law instruments (technical guidelines, plans, principles, etc.) include a notable regime, the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries (with a comprehensive, all-embracing, voluntary character), and its four International Plan of Action (IPOAs). Although the soft law instruments have no legally binding force, they have several advantages: easier to conclude and less costly to negotiate, lower “sovereignty costs” on states, more flexibility to deal with uncertainty, creating opportunities for “deeper” cooperation, dealing better with diversity, available to more participants, etc. [24] The FAO plays an important role as a venue for international fisheries management. It has concentrated on providing technical and practical assistance for countries. As to the main challenge of international implementation, its role is limited [25].

At the regional level, international regimes are implemented mainly by regional bodies. If an organization performs an advisory role, they are regional fisheries advisory bodies (RFABs) (Table 1). By providing forums for members, enhancing cooperation among members, providing information and scientific support, developing common strategies and coordination, etc., RFABs can provide important support for the regional management of fisheries [26]. UNCLOS and UNFSA provide the legal basis for the establishment of regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs), and their functions are highly recognized by FAO documents. Currently, there are around 16 RFMOs developed in different areas of the world (Table 2 and Table 3). Some of them are general RFMOs and some of them concentrate on special species (such as tuna, salmon, etc.). Different from RFABs, RFMOs have the power to adopt binding decisions. It often consists of a commission, a secretariat, a scientific committee, and a technical compliance committee. It is no doubt that RFMOs have significantly contributed to the establishment of international standards, facilitation of international cooperation, providing information and data, and monitoring and performance reviews [27].

Table 1.

Some Important RFABs.

Table 2.

General RFMOs.

Table 3.

Specialized RFMOs.

However, RFMOs have also attracted doubt and criticism. Haas et al. summarized some factors influencing the performance of RFMOs. Limited members, lack of compliance and enforcement, and political willingness of States are listed as important factors [28]. Barkin et al. (2013, 2018) pointed out that there is no central authority able to guarantee the enforcement of the binding rules and international fisheries management depends on collective action among states. RFMOs are described as a “micro-regulation”, which set total allowable catches that sometimes exceed the scientifically advised amount; and even these allowances are not facing non-compliance by members. It may cause the “balloon problem”, where fishers change their regions or species to continue their overfishing. They further proposed to establish a global macro-level regulator and an international fisheries policy [29,30]. The political willingness of the RFMO members has been questioned [31], not to say the States that have not yet participated in RFMOs. Obviously, RFMOs need to be improved and should play more important roles in regions.

Summing up, the current international fisheries management system, a dual system based on the distinction of EEZs and high seas and supplemented by specialized regional management organizations, is confronting various problems. Firstly, State activities within EEZs are difficult to regulate as international treaties only provide general principles and neither measurable standards nor binding monitoring mechanisms are provided. Secondly, on the high seas, legally binding decisions are provided by RFMOs, which face deficits such as limited membership and non-compliance. As cross-border management and international issues are relying on the participation and implementation of States, incentives and willingness are the keys to promoting cross-border management.

2.3. Fisheries Policy within the Framework of Regional Blocs: What Merits?

Regional regimes established under the current international fisheries management frameworks are mostly specialized and fragmented: States can decide which regimes to participate in and their implementation largely depends on their own will. Therefore, the key problem can be identified as promoting the incentives for States to participate in and effectively implement cross-border fisheries management. Barkin et al. (2013) proposed to establish a global and centralized regime. Under the background of anti-globalization and the changing international order at present, it is harder to be realized. Regional fisheries policies provide an alternative approach, and three merits can be identified.

Firstly, regional fisheries policy within economic blocs can set up linkages among fisheries and other issues and promote economic incentives for States to participate in regional regimes. Under the current framework, whether to attend a binding multilateral regime and follow the rules or standards set up by the regime is still based on States’ willingness. Fisheries can be a sensitive issue for coastal States. Effective fisheries management is supported from a long-term and community interests perspective. From a short-run (which may be related to domestic politics, for example, term of office) and individual States’ (the free-rider problem) perspective, effective fisheries management may not be the optimal choice for a government. Although the international community is increasingly forming an atmosphere that environmental protection and conservation of marine life are important, how deep can this moral obligation influence the decision of a government is doubtful. In addition, different countries may have different core concerns. The issue of fisheries management then may create space for negotiation and gain exchange. The incorporation of fisheries management into regional blocs will help to link different issues. Potential economic benefits (for example, possible development after joining a big market) can be an effective way to remedy the deficit of RFMOs concerning the limited members.

Secondly, regional blocs help to provide a compliance and enforcement guarantee. Although RFMOs provide legally binding decisions such as quotas, their ability to ensure the compliance and enforcement of the Member States is widely doubted [25]. Besides, fisheries management within the EEZs of the coastal States is not covered by the RFMOs. Regional fisheries policies, on the other hand, may cover a wider scope of management and set up higher standards. The increased measurability of fisheries measures and monitoring mechanisms can help to promote the effectiveness and efficiency of fisheries management. In addition, in most regional blocs, there are more available mechanisms for enforcement and disputes settlement. For example, the EU provided regional level enforcement institutions (mostly the Commission) and judicial institutions (EU courts) to guarantee the implementation of regional policies, which is discussed in detail in the next section. Another example is the “ASEAN way”, which is also adopted by the RCEP. Consultations and participation of third parties are introduced, as well as panel proceedings [32]. It is also worth noting that incorporating the fisheries policy into regional blocs itself can contribute to the improvement of the binding force concerning regional fisheries management. The increased regional integration and States’ consideration of their long-term reputation all contribute to States’ incentives to follow the decisions of the regional regimes.

Thirdly, the incorporation of fisheries management into the regional blocs helps the competent authorities of the Member States to gain technological and financial support. Good fisheries management depends not only on the willingness of a State but also on the capability of the competent authorities. Fisheries management is not costless. In contrast, good fisheries management demands solid technological and financial support to collect, analyze, and allocate data, conduct scientific research, and effectively enforce the law. Regional fisheries policy may generate “economies of scale”. For example, the regional approach is regarded as beneficial for ocean governance in the Pacific Islands, especially concerning investment and costs, capacity building, policy formulation, and international influence [33]. Better cooperation and coordination can improve the efficiency of resource utilization. It is particularly important for less-developed regions or unbalanced-developed regions.

In brief, the merits of the adoption of regional fisheries policies under regional economic frameworks mainly include increasing incentives and capabilities of States and their domestic authorities to access regional regimes and comply with the related standards or rules.

3. The EU’s Common Fisheries Policy: A Case Study

The EU has been the most successful regional regime so far in the world. It has experienced over 60 years of integration, developed from economic integration to political and social integration. African, Latin American, and Asian countries have all learned from their experience concerning regional cooperation and coordination. Although it confronts significant problems further advancing the agendas on political and security issues, its experience dealing with cross-border issues still deserves special attention. Fisheries management has been a Union-level issue. A series of legislation and institutes have been established, providing a good example for examining the effect of adopting a common fisheries policy in a regional framework.

3.1. Development of the CFP

The CFP has experienced a gradual development. In 1970, two regulations (Regulations No. 2141/70 [34] and 2142/70 [35]) were passed, laying the foundation for the CFP (on the common structural policy and the common organization of the market) [36]. The dominant idea at that time was that fish resources were sufficient and therefore, although concerns about overfishing were mentioned, the focus of the rules was more put on water access, inter-state reciprocity, fishing allocation, and productivity increase [37]. The Regulations provided general provisions calling for the Community to form common rules and granted the Council to take measures “where there is risk of overfishing [38]”. Member States were required by the Regulation to ensure equal treatment and notify and coordinate with each other concerning fishing issues. The CFP was completely established in 1983 when Regulation No. 170/83 [39] was adopted by the Council. A scheme was established, and a set of instruments based on total allowable catches (TACs) and quotas limiting the fishing effort were developed. It was proposed that the objective of the Community system is to ensure the protection of fishing grounds, the conservation of biological resources, and the long-lasting balanced exploitation of resources [40]. Since then, around every ten years, a significant reform concerning the CFP has been introduced. The CFP has been consolidated with several amendments concentrating on fisheries management and structural support in the following years.

In 1992, Regulation No. 3760/92 was adopted, in which fishing licenses were introduced. The Council was granted the competence to establish and update management objectives and management strategies. It also gained the power to determine the total allowable catch/fishing effort and distribute the fishing opportunities among the Member States. The Council was responsible for installing an EU-level control system [41]. In 2002, after realizing that fish stocks were decreasing at an even faster rate, the EU introduced three regulations: No. 2371/2002 [42] (Framework Regulation), No. 2369/2002 [43] (regarding Community structural assistance in the fisheries sector), and No. 2370/2002 [44] (concerning emergency Community measure for scrapping fishing vessels). A long-term and precautionary approach was developed by this reform, emphasizing sustainable exploitation of marine resources in environmental, economic, and social terms, which takes into consideration not only the fragile marine ecosystem but also stakeholders such as fishermen, fishing industry, and consumers [45]. The roles and voices of fishermen, experts (providing scientific, technical, and economic advice), consumers, and representatives of different sectors were stressed through the establishment of the Regional Advisory Councils (RACs). Compared with the former Regulations, the 2002 reform enlarged the scope of the CFP, highlighting the principles of “good governance [46]”, and specifying many rules concerning measures and enforcement. A more organized system was established with a clearer scientific basis, a better involvement of stakeholders, an increasing consideration of long-term plans, and a clearer division of responsibilities between the EU, national and regional levels [47,48].

In 2013, identifying some problems which had not been noticed before, the EU carried out another reform concerning its fisheries policy. Three pillars, including the regulations concerning Common Fisheries Policy (Regulation No. 1380/2013 [49]), the common organization of the markets (Regulation No. 1379/2013 [50]), and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (Regulation No. 508/2014 [51]), are supporting the current EU fisheries regime [40]. It is based on the 2013 Regulation with an amendment made in 2019. The 2013 reform introduced the principles of the maximum sustainable yield (MSY) [52]. It adjusted the emphasis of the CFP’s management of fish stocks from avoiding stock collapse to maximizing long-term yield. Markus et al. summarized several points about how it provides a more measurable, comparable, and sustainable approach concerning fish stocks [53]. The updated system encourages more quantifiable targets. In order to control the waste of marine biological resources, a discard ban was developed. An obligation to land catches on a fisheries-by-fisheries basis was stipulated with a specific timetable for different waters and the general landing obligation is not applicable (Article 15). In addition, more flexibility was introduced. For example, Member States can decide whether to use the year-to-year flexibility of up to 10% of the permitted landings (Article 15(9)) and choose to establish a system of transferable fishing concessions (Article 21). Generally speaking, existing CFP concentrates more on the concept of sustainability, quantifiability, and incentives of stakeholders. Table 4 briefly demonstrates the development of the CFP.

Table 4.

Development of the CFP.

3.2. Legal Basis and Institutions

The EU was established on a series of Treaties among the Member States. The founding Treaties include the Treaty of Paris (1951) [54], the Euratom Treaty (1957) [55], the Treaty of Rome (1957) [56], and the Treaty on European Union (TEU, 1992) [57]. Currently, the TEU and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) form the constitutional basis for the European Union [58]. The legitimacy of the CFP was questioned at the beginning as an authority to regulate fishing issues and was not explicitly granted to the European Economic Community (the EEC, now replaced by the EU) institutions by the Treaty of Rome. However, Article 38 of the Treaty provided that ‘the common market shall extend to agriculture and trade in agricultural products’, which includes ‘the products of the soil, of stock-farming and of fisheries…’ and that ‘the operation and development of the common market for agricultural products must be accompanied by the establishment of a common agricultural policy among the Member States’. Later, with the amendment of Article 3 of the TEU, the competence of adopting the CFP was explicitly given to the EU, reading ‘the activities of the Community shall include… (e) a common policy in the sphere of agriculture and fisheries’. At present, except for Article 3 of the TEU, the legal basis for the EU to adopt a CFP also includes Articles 3–4 and Articles 38–43 of the TFEU. Exclusive competence was granted to the EU concerning the conservation of marine biological resources and shared competence was given to the EU and the Member States concerning the fisheries issues other than the conservation of marine biological resources. The EU possesses the power to define, implement, and monitor the enforcement of the CFP, and EU Institutions undertake the responsibilities to make and implement the CFP [42].

It is worth noting that the enlargement of the EU has played an important role during the development of the CFP. In 1972, when the UK, Denmark, Ireland, and Norway sought to participate in the European Community (the EC, now replaced by the EU), the legal basis that applicants shall follow the fisheries policy of the community was established. In the 1972 Treaty of Accession [59], the four applicants authorized the community to restrict fishing in waters under their sovereignty or jurisdiction, and from the sixth year after accession, the Council was authorized to determine conditions for fishing [60]. The EU Court recognized the exclusive competence of the EC to adopt conservation measures for Community waters in Commission v. United Kingdom, claiming that “the transfer to the Community of powers… being total and definitive, such a failure to act (of the EC) could not in any case restore to the Member States the power and freedom to act unilaterally…” [61]. The establishment of a legal basis is very important for the formation and development of a regional fisheries policy. In the EU, both Treaties and Court rulings consolidate the CFP’s legal basis.

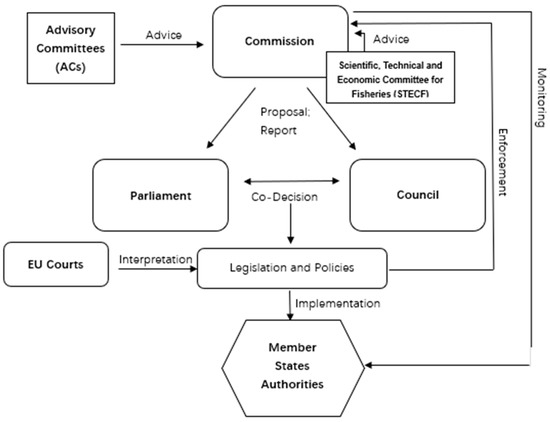

The CFP is based on “a vast mass of legislation” covering most aspects of the industry [42]. The EU has developed a complete, systematic fisheries policy framework [62]. Both EU institutions and the Member States are playing important roles in it, collectively or individually [63]. The CFP is an exclusive competence of the EU and the legislation normally takes the form of regulations. The Commission performs as an initiator and facilitator of the legislation and is responsible for negotiating with third States. It plays an important role in financial assistance and administrative work. It is also responsible for monitoring and guaranteeing the implementation of the CFP. It receives advice from the Advisory Councils (ACs) [64,65] and the Scientific, Technical, and Economic Committee for Fisheries (STECF) [66]. If there are serious threats that require immediate action, the Commission can adopt temporary measures. The Council performs as the main policy adopter, deciding the development of the CFP and the conclusion of treaties with third States. EU Parliament performs as a co-legislator with the Council on most issues, except that the authority to adopt and allocate the catch limitations solely belongs to the Council. The Council and the Parliament have to go through a negotiation process and jointly adopt regulations in relation to fisheries. The Court of Justice of the European Union, as the supranational judicial institution, made critical judgments on the competence of the EU and the Member States, especially between 1976 and 1983 [67]. It is responsible for interpreting the legislation and determining whether the legislation is followed. Member States hold voting rights in the Council. They are responsible for decision making on some matters where certain powers were delegated by the EU [68] and they are also enforcers of the CFP. Fishing opportunities are allocated to the Member States and as long as the quota determined at the EU level is not exceeded, the implementation is to be conducted at the national level and EU institutions do not have the power to act on behalf of the Member States [69] (p. 740). In terms of monitoring and inspection, a European Fisheries Control Agency (EFCA) was established in accordance with Council Regulation No. 768/2005 [70]. Its primary role is to organize coordination and cooperation between national control and inspection activities. Figure 1 below shows the EU Institutions in relation to the CFP.

Figure 1.

EU Fisheries Management Scheme. Source: Regulation (EU) No. 1380/2013, Luchman (2008) [71].

3.3. Measures Adopted in the CFP

A fisheries management scheme includes complicated institutional, economic, and social factors. In addition to appropriately designed fisheries plans, the effectiveness of a fisheries policy largely depends on the measures adopted by it. Pope (2009) provides a picture of the available measures [72]. The measure can be classified into measures controlling fleet and gears, limitation of access to the fishing ground, and input and output control. Input control (effort management) includes ex-ante instruments which regulate fishing effort. It has the advantages of being measurable and anticipatable, but because of the rapid development of technology, input control must be revised timely. Output control (catch management) includes ex-post instruments which regulate the number of fish that can be taken out of the water. Output control provides clear instructions for fishers and better protection for individual species. Possible problems with it are non-compliance and difficulties to provide an adequate scientific assessment.

In the CFP, measures are incorporated into multiannual plans, which take into consideration both single species and the whole marine ecosystem. Specific measures include technical measures concerning fishing gear, input control such as the limitation on fishing activities in certain areas or periods, and output control such as the limitation on the catch of species and sizes are stipulated. An interesting observation provided by Bellido et al. (2020) is about the regional differences between diverse regions in the EU. While fisheries in the Baltic are relatively simple and concern both fish species (three main species: herring, sprat, and cod) and fishing patterns (relatively small fleet and similar gears), the Mediterranean presents a high diversity of both. It has been noted that a good degree of compliance is better than an extensive framework which may lead to higher non-compliance. Consequently, in the Baltic Sea, output measures play an important role as it is easier for them to be enforced and in the Mediterranean, input measures are mainly used. They concluded that, therefore, even with a regional fisheries policy that establishes an institutional framework to guarantee an appropriate design of cross-border fisheries policy, better cooperation and coordination between different States, and a monitoring mechanism for the implementation of the policy, regionalized and adapted management measures are still very important [73]. The establishment of regional fisheries policy must pay special attention to the balance between the centralization and regionalization of fisheries management.

3.4. Criticism and Future of the CFP

The CFP is developed with criticisms and adjustments. Individuals, industry, and politicians have blamed the CFP for neither preventing the depletion of fish stocks in EU waters nor maintaining the traditional coastal communities [31] (p. 6). In the 2009 Green Paper on the reform of the CFP, the EU Commission examined the outcomes of the 2002 CFP reform and concluded that “the objectives agreed in 2002 to achieve sustainable fisheries have not been met overall [74]”. It reported that most fish stocks have been fished down, with 88% of stocks being fished beyond MSY and 30% outside safe biological limits. It identified five failures of the CFP that needed to be improved: a deep-rooted problem of fleet overcapacity, imprecise policy objectives, a decision-making system encouraging a short-term focus, a framework that failed to assign sufficient responsibility to the industry, and poor compliance by the industry.

The CFP has also attracted criticism and assessment from academia. The CFP was criticized especially concerning the following four problems: the control of overfishing, the incorporation and implementation of scientific advice, the enforcement of the CFP, and the participation of stakeholders. In terms of overfishing, before the introduction of MSY in 2013, an average of 59.7% of the TACs adopted by the EU was criticized as higher than those advised by the scientists [75] and the CFP failed to control excessive quotas to remedy the common pool nature of fish stocks and the inter-temporal management problem associated with fisheries [76]. In addition, the CFP did not prevent the States to pay subsidies to fishermen to support their domestic industry [69]. In terms of scientific advice, a complicated political process was regarded as having impeded the EU from effectively adopting scientific advice [77]. Several political deficiencies contributed to this problem, for example, pressure from the stakeholders who are unwilling to bear the costs of reducing catches, shortcomings associated with the electoral politics, and political devaluation of fisheries science, etc. [72]. The CFP was also criticized for experiencing insufficient enforcement. Although the CFP is an exclusive competence of the Union, enforcement of it relies on both EU institutions and national authorities. An important weakness of the CFP identified is the poor enforcement of the Member States concerning fisheries management [78,79]. Strong resistance to reform of the CFP also increased the difficulties of improving the management system [80]. As to the stakeholders, collusion between the fisheries industry and advisers is one important factor leading to the lack of success of the CFP [81]. The ACs are dominated by the fisheries industries and many other interest groups have less influence on AC recommendations [82]. Strong lobbies in favor of the fisheries industry and transparency problems existing in both management measures and the decision-making process may lead to less inclusion of stakeholders [76].

The reforms of the CFP have responded to criticisms. The principle of “good governance” is stipulated in a more detailed manner in the 2013 Regulation [83], which identified the shortcomings of the old CFP and the directions of the future CFP. It provides that,

The CFP shall be guided by the following principles of good governance:

- (a)

- the clear definition of responsibilities at the Union, regional, national, and local levels;

- (b)

- the taking into account of regional specificities, through a regionalized approach;

- (c)

- the establishment of measures in accordance with the best available scientific advice;

- (d)

- a long-term perspective;

- (e)

- administrative cost efficiency;

- (f)

- appropriate involvement of stakeholders, in particular the Advisory Council, at all stages—from conception to implementation of the measures;

- (g)

- the primary responsibility of the flag State;

- (h)

- consistency with other Union policies;

- (i)

- the use of impact assessments as appropriate;

- (j)

- coherence between the internal and external dimensions of the CFP

- (k)

- transparency of data handling in accordance with existing legal requirements, with due respect to private life, the protection of personal data, and confidentiality rules; availability of data to the appropriate scientific bodies, other bodies with a scientific or management interest, and other defined end-users.

The outcomes of the reformed CFP and further reforms are awaiting future observation. Some data, however, have already demonstrated a positive trend. In the report issued by the EU STECF in 2020 [84], from 2003 to 2018, the number of stocks where fishing mortality exceeded the scientifically calculated maximum fishing pressure (FMSY) has experienced a drop from 45 to 26 while the number of stocks where fishing mortality was equal to or less than FMSY has doubled from 18 to 42. The number of stocks outside safe biological limits has decreased from 31 to 14, while the number of stocks inside safe biological limits has increased from 13 to 30. In addition, an increase in the biomass of some stocks has also occurred. The data demonstrate a better sustainability of fisheries in the EU, while the performance does not change that much in other parts of the world. These figures present a positive outcome of the CFP. The CFP has also received some positive feedback from academia. Belschner examined the CFP based on 17 evaluation criteria in five dimensions (ecological, economic, social, good governance, and evidence) in 2019. Except for five criteria, namely, simplicity of rules, user-pays principle, resource efficiency, accountability, and compliance mechanisms, the CFP either works well or shows a positive trend regarding all other criteria [85].

Currently, both scholars and practitioners are engaged in exploring a better CFP. Attention is particularly devoted to the following points: (1) the mechanisms concerning the fishing rights such as individual transferable quotas (ITQs) [86]; (2) stakeholder participation and balance between interest groups [66,87,88,89,90,91]; (3) integration and utilization of multiple sources of knowledge such as policymakers, scientists, and stakeholders based on an ecosystem approach [92]; (4) a framework incorporating fisheries into the management of the whole marine ecological systems [93]; and, (5) regionalization and multi-level governance of the fisheries; put differently, co-management and shared-enforcement of the CFP [57,94].

4. Lessons Learned: Pursuing a More Effective Cross-Border Fisheries Management

What lessons can be learned from the EU’s experience of fisheries management? Different people may have different opinions. Some people may question the effectiveness of the CFP and some may question whether the EU experience can be applied in other regions). It is well acknowledged that the regional integration of the EU cannot be simply duplicated by other regions considering different regions are facing different conditions and challenges. The CFP was formed and developed in the process of creating and developing a supra-national regional organization (the EU). States authorized (part of) their legislative, administrative, and judicial powers to EU institutes. A harmonized Union-level fisheries policy and a centralized implementation system were created. In the near future, it will be hard to find another region having the same motivation and ability to create a similar supra-national regional organization. However, observing the 50-year evolution of the EU fisheries policy, some precious lessons can still be identified.

4.1. Finding the Economic Common Interests

The CFP was formed when the EU integration was promising and attractive. Although not all Member States were happy with the CFP and had to give up some important powers to the EU (exclusive power of the EU concerning the conservation of living resources), possible benefits of an integrated market prevailed. States still had the willingness to access and be bound by EU law. Linkage of fisheries with other issues through the regional economic blocs is an important factor leading to the success of the CFP. The EU not only provides a framework to link fisheries issues with other important issues but also provides a forum for the Member States to negotiate and make compromises on different interests in a practical way. The potential benefit of regional integration and welfare improvement (especially to less-developed countries) is very appealing, so the high-standard requirements and the loss of some powers are acceptable to countries willing to access the EU. Today, with environmental protection and conservation of living resources becoming increasingly important, how to generate States’ incentives to work cooperatively on common issues faced by the international community is worth noting. Introducing an outer or higher-level authority may help to remedy the short-run deficit of individual governments. Special attention should be imposed on the establishment and improvement of regional regimes, especially finding common interests to promote effectiveness and efficiency.

The CFP has gone through a gradual formation and development. In the beginning, it started with a limited number of parties, an emphasis on equal access to waters, and common interests among members. General and vague provisions were provided, which helped set up a common consensus. Later, more complementary and detailed provisions adopting a long-term and sustainable approach were developed. The competence and responsibility of the institutions were gradually clarified, the scope of the CFP was expanded, clearer objectives were provided, more instruments were introduced, and better decision-making and enforcement mechanisms were developed. Evolving together with international law and the world’s latest research concerning fisheries, the CFP provided a good regime connecting the most advanced works with the fisheries management in the EU. It can be learned that a step-by-step approach should be advocated. The first step is always the hardest and a too ambitious goal will affect the motivation of participants and the effectiveness of the regime. By finding common interests and fostering further common interests, regional regimes can become more detailed and enforceable.

4.2. Institutional Design for Better Enforcement

It has been mentioned that regional blocs can provide compliance and dispute resolution mechanisms for members and therefore guarantee the enforcement of regional policies. The effectiveness of a policy depends on its enforcement. The good design of related institutes is important. In the EU, there are clear rules concerning the competence, decision-making process, and responsibilities of the institutes. A complementary set of institutes, including the decision-making authorities, administrative and monitoring authorities, and scientific advisory authorities, are developed, helping to promote the implementation of the CFP. Moreover, the Courts not only provide interpretation for the legal basis of the CFP but also provide a judicial remedy for all Member States.

However, it is notable that institutional design is never easy [95]. The structural establishment of fisheries management in the EU followed a trend of decentralization–centralization–regionalization. The CFP has followed a top-down approach since its establishment in 1983 when the competition was exclusively granted to the EU and the authority was generally centralized. However, with the language of the policy being more detailed and inclusive, institutions and enforcement must find a balance between robust and flexible [96]. Currently, the EU has adopted a system in which the EU institutions make the policy and monitor its application, while Member States are largely counted on to enforce the CFP. The recent works concerning the CFP have paid more attention to the “moving down” (decentralization) and “moving out” (involvement of stakeholders) [97]. Nevertheless, if there never was “centralization”, there would never have been “decentralization”. The primary task of the CFP is to find a balance between centralization (higher-level force for insufficient national fisheries management) and localization (optimal choices based on local conditions). For other regions in the world, regional institutional design and allocation of powers have to be based on specific economic, political, and environmental conditions in those regions. A general approach is that an efficient system of institutions should be established with a balance of certain centralized competence and regionalized participation.

4.3. Financial Support, Scientific Advice, and Quantification

A clear trend demonstrated by the CFP is the increasing emphasis on scientific advice and quantification. An important way of ensuring the compliance and effectiveness of enforcement is providing measurable standards based on scientific advice. Regarding the CFP, administrative work, including financial support and monitoring of enforcement, is conducted by the EU Commission, and several scientific organizations are established to serve the decision making and implementation. Fisheries cover a combination of natural science and socio-economic science. Effective management of fisheries requires good skills and scientific support, which are less accessible to less-developed countries. Within a regional economic bloc, resources can be gathered and better allocated, creating scientific and financial support for the weaker members. Through the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF), the EU provides financial support for the implementation of maritime policies (it is jointly managed by the EU Commission and the Member States) [98]. In the 2013 reform, the CFP set obligations for the Member States to timely collect and make data available [99]. Through the ACs and STECF, the EU collected, analyzed, and allocated data and information. It also provided good practice for members to follow. This financial and technological support helps to promote the capacity of national authorities, especially of the poorer Member States. The lesson that can be learned by other regions is that pooling the resources and making efficient use of them is very important.

5. Discussion and Concluding Remarks

Fisheries management is critical to many economic and social structures: fishermen, associated industries, physical environment, policymakers, monitors, etc. This paper is inspired by observations of anti-globalization and the potential of regionalization, as well as the current unsatisfactory international fisheries management schemes, especially the RFMOs. Many scholars have devoted their attention to the drawbacks of the current regional fisheries schemes [29,30,31], among which the incentive issue is particularly crucial, both for attracting States to participate in regional fisheries management and for guaranteeing an effective implementation of regional policies. Can the existing RFMOs make further efforts and encourage regional fisheries management in a more efficient way? Maybe, but the specialized characteristic of the RFMOs set an inherent limit for their ability to be more appealing, especially considering fisheries management requires capacity building, investment, and technological development. Put differently, the costs of participating in RFMOs are high and foreseeable, while the benefits may be uncertain and invisible (the free-rider problem). Therefore, regional fisheries management needs to be combined with more economic motivations. The idea then arises: what about combining the fisheries policy and the regional economic integration?

There is a good example that has gained 50 years of experience: the EU. Theoretically, the incorporation of fisheries management into regional economic blocs can help to establish issue linkage and improve incentives for States to take part in, guarantee the compliance and enforcement of the members, and improve technological and financial support for competent authorities. The EU’s experience with the CFP has proved this. The CFP adopted under the EU framework has helped to improve economic incentives by linking different issues, promoted compliance and enforcement by providing an institutional guarantee, and provided better scientific and financial support by pooling resources. No doubt, there is still significant room for improvement for the CFP, especially concerning decision making (incorporation of scientific advice), the balance between centralization and localization, and effective implementation. It is also well recognized that the EU experience may not be suitable for other regions in the world. For example, the EU institutes enjoy powers authorized by the Member States and good financial conditions. In addition, the importance of the conservation of marine life has been widely accepted by the EU people. These conditions are not ready for many other regions. Nevertheless, it is notable that the evolution of the CFP is not accomplished in one move. Considering the potential economic integration and regionalization in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, exploring the incorporation of fisheries management into a complementing regional economic bloc is significant. In this process, economic incentives, good design of institutes, and scientific and financial support are always important aspects.

Funding

This research was funded by “Dalian Academy of Social Science”, grant number 2021dlsky010, “Legal Issues concerning Dalian’s Participation in the China-Japan-Korea Market Integration” and “the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities”, Dalian Maritime University, grant number 3132022296, “Sources of International Law and States’ Marine Rights”.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Chang Yen-Chiang for his kind and insightful advice.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- O’Rourke, K.H. Economic history and contemporary challenges to globalization. J. Econ. Hist. 2019, 79, 356–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enderwick, P.; Buckley, P.J. Rising regionalization: Will the post-COVID-19 world see a retreat from globalization? Transnatl. Corp. J. 2020, 27, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.A. Trading Fish, Saving Fish: The Interaction between Regimes in International Law; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 34–55. [Google Scholar]

- Schimmelfennig, F.; Winzen, T. Differentiated EU integration: Maps and modes. Robert Schuman Cent. Adv. Stud. Res. Pap. No. RSCAS 2020, 24, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tieku, T.K. The African Union: Successes and failures. Oxf. Res. Encycl. Politics 2019. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/politics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-703 (accessed on 22 April 2022). [CrossRef]

- Hart-Landsberg, M. Capitalist Globalization: Consequences, Resistance, and Alternatives; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hart-Landsberg, M. From the claw to the lion: A critical look at capitalist globalization. Crit. Asian Stud. 2015, 47, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bello, W. Deglobalization: Ideas for a New World Economy; Zed Books Ltd.: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Held, D.; McGrew, A. Globalization/Anti-Globalization: Beyond the Great Divide; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, R.C. Globalization in retreat-further geopolitical consequences of the financial crisis. Foreign Aff. 2009, 88, 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Muja, A.; Hajrizi, E.; Groumpos, P.; Metin, H. The globalization paradox in 21st century and its applicability in analysis of international stability. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destek, M.A. Investigation on the role of economic, social, and political globalization on environment: Evidence from CEECs. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 33601–33614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghilès, F. Globalization and Its Critics. 2020. Available online: https://www.cidob.org/en/publications/publication_series/opinion/seguridad_y_politica_mundial/globalization_and_its_critics (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Wang, Z.; Sun, Z. From globalization to regionalization: The United States, China, and the post-COVID-19 world economic order. J. Chin. Political Sci. 2021, 26, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, W.R. The regional subsystem: A conceptual explication and a propositional inventory. Int. Stud. Q. 1973, 17, 89–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, M.H.; Kose, M.A.; Otrok, M.C. Regionalization vs. Globalization; International Monetary Fund: Bretton Woods, NH, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Börzel, T.A.; Risse, T. (Eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Regionalism; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Söderbaum, F. Old, new, and comparative regionalism. In The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Regionalism; Börzel, T.A., Risse, T., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 16–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hveem, H. Explaining the regional phenomenon in an era of globalization. Political Econ. Chang. Glob. Order 2000, 2, 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Yeo, L.H. Institutional regionalism versus networked regionalism: Europe and Asia compared. Int. Politics 2010, 47, 324–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, G. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumaila, U.R.; Bellmann, C.; Tipping, A. Fishing for the future: An overview of challenges and opportunities. Mar. Policy 2016, 69, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chronological Lists of Ratifications of, Accessions and Successions to the Convention and the Related Agreements, United Nations. Available online: https://www.un.org/depts/los/reference_files/chronological_lists_of_ratifications.htm (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Shaffer, G.C.; Pollack, M.A. Hard vs. soft law: Alternatives, complements, and antagonists in international governance. Minn. Law Rev. 2010, 94, 706–799. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen, T. The FAO and ocean governance. In The IMLI Treatise on Global Ocean Governance: Volume II: UN Specialized Agencies and Global Ocean Governance; Attard, D.J., Fitzmaurice, M., Ntovas, A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Terje Løbach, T.; Petersson, M.; Haberkon, E.; Mannini, P. Regional fisheries management organizations and advisory bodies. Activities and developments, 2000–2017. FAO Fish. Aquac. Tech. Pap. 2020, 651, 1–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, J. Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing: Are RFMOs Effectively Addressing the Problem? In Ocean Yearbook Online; Brill: Leidon, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, B.; McGee, J.; Fleming, A.; Haward, M. Factors influencing the performance of regional fisheries management organizations. Mar. Policy 2020, 113, 103787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkin, J.S.; DeSombre, E.R. Do we need a global fisheries management organization? J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2013, 3, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkin, J.S.; DeSombre, E.R.; Ishii, A.; Sakaguchi, I. Domestic sources of international fisheries diplomacy: A framework for analysis. Mar. Policy 2018, 94, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodge, M.W.; Anderson, D.; Løbach, T.; Munro, G.; Sainsbury, K.; Willock, A. Recommended Best Practices for Regional Fisheries Management Organizations: Report of an Independent Panel to Develop a Model for Improved Governance by Regional Fisheries Management Organizations; Chatham House: Chatham, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Massimo, L. Enhancing conflict resolution ‘ASEAN way’: The Dispute Settlement System of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. J. Int. Disput. Settl. 2022, 13, 98–120. [Google Scholar]

- Power, M. The regional scale of ocean governance regional cooperation in the Pacific Islands. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2002, 45, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EEC) No 2141/70 of the Council of 20 October 1970 Laying down a Common Structural Policy for the Fishing Industry, OJ L 236, 27.10.1970. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A31970R2141 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Regulation (EEC) No 2142/70 of the Council of 20 October 1970 on the Common Organization of the Market in Fishery Products, OJ L 236, 27.10.1970. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A31970R2142 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Schweiger, L. The Evolution of the Common Fisheries Policy: Governance of a Common-Pool Resource in the Context of European Integration. No. 7; Institute for European Integration Research (EIF): Vienna, Austria, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Laxe, F.G. The European Common Fisheries Policy: An Economic Approach to Overfishing Solutions. In Too Valuable to be Lost: Overfishing in the North Atlantic Since 1880; Garrido, A., Starkey, D., Eds.; De Gruyter Oldenbourg: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 129–146. [Google Scholar]

- Article 5 of Regulation 2141/70. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A31970R2141 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Council Regulation (EEC) No 170/83 of 25 January 1983 Establishing a Community System for the Conservation and Management of Fishery Resources, OJ L 24, 27.1.1983. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A31983R0170 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Article 1 of Regulation 170/83. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A31983R0170 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Council Regulation (EEC) No 3760/92 of 20 December 1992 Establishing a Community System for Fisheries and Aquaculture, OJ L 389, 31.12.1992. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:31992R3760 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Council Regulation (EC) No 2371/2002 of 20 December 2002 on the Conservation and Sustainable Exploitation of Fisheries Resources under the Common Fisheries Policy, OJ L 358, 31.12.2002. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32002R2371 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Council Regulation (EC) No 2369/2002 of 20 December 2002 Amending Regulation (EC) No 2792/1999 Laying down the Detailed Rules and Arrangements Regarding Community Structural Assistance in the Fisheries Sector, OJ L 358, 31.12.2002. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32002R2369 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Council Regulation (EC) No 2370/2002 of 20 December 2002 Establishing an Emergency Community Measure for Scrapping Fishing Vessels, OJ L 358, 31.12.2002. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=uriserv%3AOJ.L_.2002.358.01.0057.01.ENG (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- The Common Fisheries Policy: Origins and Development, EU Parliament Fact Sheets on the European Union. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/en/sheet/114/the-common-fisheries-policy-origins-and-development (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Chang, Y.C. International legal obligations in relation to good ocean governance. Chin. J. Int. Law 2010, 9, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, R.; Owen, D. The EC Common Fisheries Policy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Sissenwine, M.; Symes, D. Reflections on the Common Fisheries Policy. Report to the General Directorate for Fisheries and Maritime Affairs of the European Commission. 2007. Available online: https://www.fishsec.org/app/uploads/2011/03/1201534052_04993.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Regulation (EU) No 1380/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2013 on the Common Fisheries Policy, amending Council Regulations (EC) No 1954/2003 and (EC) No 1224/2009 and Repealing Council Regulations (EC) No 2371/2002 and (EC) No 639/2004 and Council Decision 2004/585/EC, OJ L 354, 28.12.2013. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32013R1380 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Regulation (EU) No 1379/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2013 on the Common Organisation of the Markets in Fishery and Aquaculture Products, Amending Council Regulations (EC) No 1184/2006 and (EC) No 1224/2009 and Repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 104/2000, OJ L 354, 28.12.2013. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32013R1379 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Regulation (EU) No 508/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 May 2014 on the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund and repealing Council Regulations (EC) No 2328/2003, (EC) No 861/2006, (EC) No 1198/2006 and (EC) No 791/2007 and Regulation (EU) No 1255/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council, OJ L 149, 20.5.2014. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32014R0508&qid=1651116823617 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Article 2 (2) of Regulation 1380/2013. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/LSU/?uri=celex%3A32014R0508 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Salomon, M.; Markus, T.; Dross, M. Masterstroke or paper tiger—The reform of the EU’s Common Fisheries Policy. Mar. Policy 2014, 47, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Coal and Steel Community. Treaty Establishing the European Coal and Steel Community; European Coal and Steel Community: Paris, France, 1951; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=LEGISSUM%3Axy0022 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Treaty establishing the European Atomic Energy Community, 25 March 1957. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A11957A%2FTXT (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, 25 March 1957. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/HR/TXT/?uri=celex:11957E/TXT (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Treaty on European Union, 7 February 1992, OJ C 191, 29.7.1992. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:11992M/TXT (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, 13 December 2007, OJ C 306, 17.12.2007. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:12012E/TXT (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Treaty of Accession of Denmark, Ireland and the United Kingdom (1972), OJ L 73, 27.3. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ%3AL%3A1972%3A073%3ATOC (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Article 100 and 102 of the 1972 Treaty of Accession. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ%3AL%3A1972%3A073%3ATOC (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Case 804/79, Commission of the European Communities v United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (1981), ECLI:EU:C:1981:93, Para 20. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=ecli:ECLI:EU:C:1981:93 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Hegland, T.J. The Common Fisheries Policy and Competing Perspectives on Integration. 2009. Available online: http://vbn.aau.dk/files/18148509/Hegland_MLG_paper_for_publication_20med_20omslag_1_.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Articles 11-24 of Regulation 1380/2013. Available online: http://vbn.aau.dk/files/18148509/Hegland_MLG_paper_for_publication_20med_20omslag_1_.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- The Advisory Councils (ACs) are Stakeholder-Led Organizations Providing Recommendations for the Commission and EU Countries. They Include Aquaculture AC, Baltic Sea AC, Black Sea AC, Long Distance AC, Market AC, Mediterranean Sea AC, North Sea AC, North-Western Waters AC, Outermost Regions AC, Pelagic Stocks AC, South-Western Waters AC. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/oceans-and-fisheries/fisheries/scientific-input/advisory-councils_en (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Hatchard, J.; Gray, T.S. From RACs to Advisory Councils: Lessons from North Sea discourse for the 2014 reform of the European Common Fisheries Policy. Mar. Policy 2014, 47, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- The Scientific, Technical and Economic Committee for Fisheries (STECF) Is a Scientific Body Established by the Commission Providing Scientific Advice to the Commission. For More Information, See STECF Website. Available online: https://stecf.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Lado, E. Wiley-Blackwell. For example, the Kramer (1976), EC v. Ireland (1978), Commission v. United Kingdom (1981). The Court played a critical role in advancing EU integration on the fisheries issues. In The Common Fisheries Policy: The Quest for Sustainability; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- For Example, Member States Have the Competence to Decide How to Allocate Fishing Opportunities to Vessels and Exchange All or Part of the Fishing Opportunities Allocated to Them. Article 16 of Regulation 1380/2013. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32013R1380 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Frost, H.; Andersen, P. The common fisheries policy of the European Union and fisheries economics. Mar. Policy 2006, 30, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council Regulation (EC) No 768/2005 of 26 April 2005 Establishing a Community Fisheries Control Agency and Amending Regulation (EEC) No 2847/93 Establishing a Control System Applicable to the Common Fisheries Policy, OJ L 128, 21.5.2005, pp. 1–14; Now Replaced by Regulation (EU) 2019/473 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 March 2019 on the European Fisheries Control Agency, OJ L 83, 25.3.2019, pp. 18–37. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32019R0473 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Lutchman, I.; Adelle, C. EU Fisheries Decision Making Guide; Fisheries Secretariat: Stockholm, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, J. Input and output controls: The practice of fishing effort and catch management. In Fishery Manager’s Guidebook, 2nd ed.; Cochrane, K., Garcia, S.A., Eds.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2009; p. 220. [Google Scholar]

- Bellido, J.M.; Sumaila, U.R.; Sánchez-Lizaso, J.L.; Palomares, M.L.; Pauly, D. Input versus output controls as instruments for fisheries management with a focus on Mediterranean fisheries. Mar. Policy 2020, 118, 103786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Paper—Reform of the Common Fisheries Policy, COM/2009/0163 final. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/policy-documents/com-2009-163-final-green.2009 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Borges, L. Setting of total allowable catches in the 2013 EU common fisheries policy reform: Possible impacts. Mar. Policy 2018, 91, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilian, S.; Froese, R.; Proelss, A.; Requate, T. Designed for failure: A critique of the Common Fisheries Policy of the European Union. Mar. Policy 2010, 34, 1178–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daw, T.; Gray, T. Fisheries science and sustainability in international policy: A study of failure in the European Union’s Common Fisheries Policy. Mar. Policy 2005, 29, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- José-María, D.; Santiago, C.; Sebastian, V. The Common Fisheries Policy: An enforcement problem. Mar. Policy 2012, 36, 1309–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliantonio, M.; Cacciatore, F. When the EU takes the field. Innovative forms of regulatory enforcement in the fisheries sector. J. Eur. Integr. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raakjær, J. A Fisheries Management System in Crisis: The EU Common Fisheries Policy. 2009. Available online: https://www.ices.dk/sites/pub/CM%20Doccuments/CM-2009/R/R0109.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Froese, R. Fishery reform slips through the net. Nature 2011, 475, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Linke, S.; Dreyer, M.; Sellke, P. The regional Advisory Councils: What is their potential to incorporate stakeholder knowledge into fisheries governance? AMBIO 2011, 40, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Article 3 of Regulation 1380/2013. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32013R1380 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Publications Office of the European Union. STECF: Monitoring the Performance of the Common Fisheries Policy; STECF Adhoc 20-01; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Belschner, T.; Ferretti, J.; Strehlow, H.V.; Kraak, S.B.; Döring, R.; Kraus, G.; Kempf, A.; Zimmermann, C. Evaluating fisheries systems: A comprehensive analytical framework and its application to the EU’s Common Fisheries Policy. Fish Fish. 2019, 20, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjimichael, M. A call for a blue degrowth: Unravelling the European Union’s fisheries and maritime policies. Mar. Policy 2018, 94, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linke, S.; Svein, J. Ideals, realities and paradoxes of stakeholder participation in EU fisheries governance. Environ. Sociol. 2016, 2, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirill, O.; Schlüter, M.; Österblom, H. Tracing a pathway to success: How competing interest groups influenced the 2013 EU Common Fisheries Policy reform. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 76, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aanesen, M.; Armstrong, C.W.; Bloomfield, H.J.; Röckmann, C. What does stakeholder involvement mean for fisheries management? Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, R. The role of regional advisory councils in the European common fisheries policy: Legal constraints and future options. Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law 2010, 25, 289–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pita, C.; Pierce, G.J.; Theodossiou, I. Stakeholders’ participation in the fisheries management decision-making process: Fishers’ perceptions of participation. Mar. Policy 2010, 34, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Monsalve, P.; Raakjær, J.; Nielsen, K.N.; Santiago, J.L.; Ballesteros, M.; Laksá, U.; Degnbol, P. Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management (EAFM) in the EU–Current science–policy–society interfaces and emerging requirements. Mar. Policy 2016, 66, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigagli, E. The EU legal framework for the management of marine complex social–ecological systems. Mar. Policy 2015, 54, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliasen, S.Q.; Hegland, T.J.; Raakjær, J. Decentralising: The implementation of regionalisation and co-management under the post-2013 Common Fisheries Policy. Mar. Policy 2015, 62, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, D.C. Policy-making in nested institutions: Explaining the conservation failure of the EU’s Common Fisheries Policy. JCMS J. Common. Mark. Stud. 2000, 38, 303–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentoft, S. Introduction: Institutions for fisheries governance. In Fish for Life: Interactive Governance for Fisheries; Kooiman, J., Bavinck, M., Jentoft, S., Pullin, R., Eds.; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 147–152. [Google Scholar]

- Raakjær, J.; Degnbol, P.; Hegland, T.J.; Symes, D. Regionalisation-what will the future bring? Marit. Stud. 2012, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Maritime and Fisheries Fund, the EU Commission. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/oceans-and-fisheries/funding/european-maritime-and-fisheries-fund-emff_en (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Article 25 of Regulation 1380/2013. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32013R1380 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).