1. Introduction

Since the adoption of Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development at the United Nations Ocean Conference in 2015, the concept of sustainable development has been widely applied across various industries, and the awareness of sustainable development among governments and the public has gradually increased. Economic, social, and environmental pillars have gradually become the core framework of sustainable development [

1,

2]. Rather than replacing these three pillars, factors such as management and culture—proposed by some scholars [

3]—act as critical sub-components to supplement them: management (e.g., fishery regulatory systems, cross-sector coordination mechanisms) enhances the implementation efficiency of the three pillars, while culture (e.g., local fishing community traditions, sustainable development awareness) strengthens their social adaptability. These supplementary perspectives have been widely accepted in academia, driving continuous deepening of sustainable development research. In addition, this study emphasizes that scientific and technological innovation further empowers the three pillars—for instance, China’s independently developed, fully submersible, deep-sea intelligent aquaculture equipment has boosted mariculture productivity by 30% while reducing environmental impact [

4], demonstrating tech’s role in advancing marine fisheries sustainability.

The sustainable development of marine fisheries is a key focus of global concern, closely tied to SDG14 (“Life Below Water”)—the United Nations’ goal to conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development. Achieving SDG 14 is critical to safeguarding global socio-economic health and human well-being, as marine fisheries provide high-quality protein for billions and support livelihoods worldwide.

Marine fisheries are a fundamental industrial sector in the socio-economic development of various countries. Though there is currently no internationally unified definition and standard for “sustainable fisheries” and “sustainable marine fisheries”, the issue of sustainable development in fisheries has received widespread attention from the international community. Developed, developing, and less developed countries have all realized that seafood is an important agricultural product and a significant source of high-quality animal protein [

5]. The current and future development of marine fisheries faces many challenges, including the decline and depletion of fishing resources, global climate warming and abnormal increase in seawater temperature caused by the El Niño phenomenon, ocean acidification, ecological environmental pollution, labor shortage, aging infrastructure, and the impact of emergencies [

6,

7,

8]. Many countries and regions are actively addressing these challenges. For example, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) of the United States released the first version of the National Seafood Strategy in August 2023, focusing on sustainably managing marine fisheries and responsibly producing seafood. The European Commission is committed to building an “Energy Transition Partnership for EU Fisheries and Aquaculture” as a key action to promote the energy transition of fishing and aquaculture industries, aiming to bring together all stakeholders to achieve net-zero carbon emissions in fisheries and aquaculture by 2050. China has also integrated the concept of green and low-carbon development into the development mode of the marine economy and taken actions, such as carrying out the construction of marine ranching. By 2023, China had created 169 national-level marine ranching demonstration zones, which generate nearly 178.1 billion yuan in ecological benefits annually [

4]. The fully submersible deep-sea intelligent fishery breeding equipment independently developed by China has been put into operation, and new technologies and models for green breeding in deep and open seas are increasing [

4].

Meanwhile, human demand for high-quality and healthy seafood is continuously growing, and per capita seafood consumption is steadily increasing. However, the proportion of marine fisheries’ stocks within the biologically sustainable range around the globe is declining, marking a drop from 90% in 1974 to 62.3% in 2021 [

9,

10]. According to expert estimates, China’s seafood consumption demand in 2035 is expected to exceed the national apparent consumption in 2023 by approximately 14.5 million tons [

11]. Recently, scholars have pointed out that current fishery resource assessment models overestimate the sustainability of global fisheries and that natural mortality rates and population replenishment relationships have a significant impact on the accuracy of assessment results [

12]. Since 2021, the FAO has been promoting the “Blue Transformation” initiative—anchored in three core components outlined in its recent documents [

10]: (1) Sustainable production intensification (e.g., optimizing aquaculture efficiency and reducing capture fisheries overexploitation), (2) Equitable benefit distribution (ensuring small-scale fishermen and coastal communities access to markets and livelihood support), and (3) Ecosystem resilience enhancement (mitigating fisheries’ environmental impact and adapting to climate change). This initiative aims to maximize the aquatic food system’s contribution to food security, nutrition improvement, and poverty reduction, in line with the “2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.” The supporting “Blue Transformation Roadmap” further operationalizes these three components, targeting sustainable growth in fisheries and aquaculture while advancing the equitable sharing of benefits and environmental protection.

How much food can the ocean sustainably provide in the future? Some scholars have superimposed the supply curve on the demand scenario and predicted that the amount of food provided by the ocean may increase by 21–44 million tons by 2050, equivalent to approximately 12–25% of the additional meat required to feed 9.8 billion people by 2050 [

13]. However, the growth of seafood is influenced by various factors, and there are still many uncertainties and instabilities.

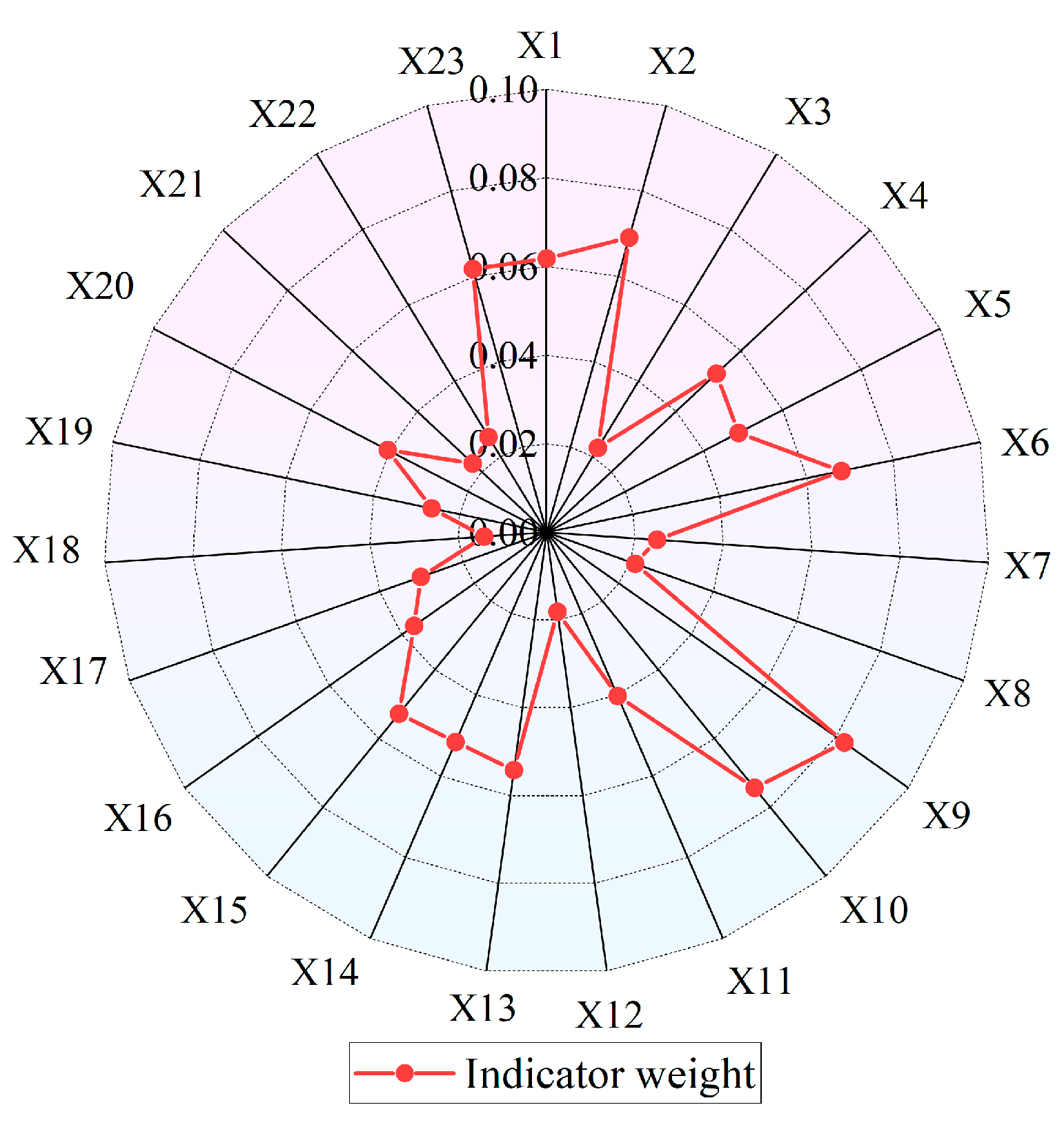

China is the world’s largest fishing country, and its aquaculture production is also in a leading position globally. Its marine fishing output and mariculture production rank among the top in the world. The Blue Transformation of China’s marine fisheries has a positive impact on achieving the goals of SDG14 and the sustainable development of global fisheries. This study aims to explore several key issues regarding the sustainable development trend of China’s marine fisheries. Firstly, we construct an evaluation system for China’s marine fisheries’ sustainable development potential across economic, social, and resource-environmental dimensions. To cover the 2021–2030 study period, we use two complementary models with distinct roles: the GM(1,1) model (a gray forecasting tool) to predict the 2024–2030 time-series data of core evaluation indicators (e.g., marine aquaculture area, number of fisheries patents)—supplementing the observed 2021–2023 data—and the entropy weight-TOPSIS method (an objective evaluation tool with entropy weight for indicator weighting) to calculate the comprehensive sustainable development potential index for the entire 2021–2030 period. Secondly, combined with domestic and international situations, we analyze the impact of various factor changes on the sustainable development potential of marine fisheries. Finally, based on the prediction results, analysis of influencing factors, as well as China’s local fisheries policies, international fisheries policies, and related actions, we innovatively propose development recommendations for achieving Blue Transformation and sustainable development of China’s marine fisheries. By exploring these research issues, we aim to provide new insights and tailored Chinese development ideas and solutions for the “Blue Transformation” and sustainable development of global fisheries and also offer references and insights for the development of fisheries in other countries.

2. Overall Development of China’s Marine Fisheries

China has continuously improved its marine governance level and strengthened the sustainable utilization of fishery resources. Since the implementation of the system of summer moratorium of marine fishing in 1995, China has continuously extended the fishing moratorium period and expanded the scope of the moratorium, controlled the intensity of marine fishing, and protected and restored fishery resources. Since 2003, China has successively implemented the total management system of marine fisheries resources, the fishing license system, and the “dual control” system of the number of marine fishing boats and their powers and explored the implementation of fishing quota management by species and region, promoted the increase in marine product production, and carried out the construction of national-level marine ranching. China has continued to improve the marine environment and provide favorable guarantees for the development of marine fisheries. According to data from the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China, in 2023, the proportion of excellent water quality in China’s coastal waters reached 85%, which marks a record high, an increase of 13.7 percentage points compared to 2018, and “six consecutive years of growth”. Since 2021, 24 typical marine ecosystems have eliminated the “unhealthy” conditions.

According to the statistics and reports from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), China continued to maintain its position as a major producer in 2022 and produced 36% of the total output; China’s fishing output accounted for about 14.3% of the global total, while its aquaculture output accounted for about 60% of the global total. China is also the world’s second largest importer of aquatic products, with its imports accounting for about 12% of the global total, second only to 17% of the United States [

10].

According to China’s official statistics, in 2023, China’s total aquatic product output reached 71.1617 million tons, registering a year-on-year increase of 3.64%. The ratio of marine product output to freshwater product output stood at 50.4:49.6, with marine product output slightly exceeding that of freshwater product [

14]. In the first three quarters of 2024, marine fishing output amounted to 6.4117 million tons, marking a year-on-year growth of 1.62%, while marine aquaculture output reached 18.1511 million tons, registering a year-on-year growth of 5.67% [

15]. Rabobank predicts that China’s seafood consumption will increase by 5.5 million tons by 2030. Calculated at the prices of 2023, China’s fishery output value amounted to 1.595735 trillion yuan, comprising 261.831 billion yuan from marine fishing and 488.548 billion yuan from marine aquaculture. Regarding the income of fishermen, a survey on the income and expenditure of nearly 10,000 fishermen’s families in China revealed that the per capita net income of Chinese fishermen in 2023 was 25,777.21 yuan, marking a year-on-year growth of 4.72%. In terms of factor input, the national aquaculture area in 2023 reached 7624.60 thousand hectares, of which the marine aquaculture area reached 2214.87 thousand hectares, marking a year-on-year growth of 6.77%. From the international perspective, pond aquaculture in most coastal countries is more than three times the size of marine aquaculture. However, the difference in scale between marine aquaculture and pond aquaculture in China is relatively small, and the vast onshore pond aquaculture space can accommodate marine fish. Additionally, the development of saline-alkali land and facility fisheries is rapidly advancing [

16].

4. Facing 2030: Key Influencing Factors for the Sustainable Development of China’s Marine Fisheries

Many coastal countries and regions, including China, have high hopes for the development of the fishing industry and aspire to enhance its contribution to regional economy and employment. However, the development of the fishing economy is influenced by many factors—broadly categorized into objective and subjective factors in the long run—and their impacts are reflected in the sustainable development potential index: for example, objective factors like the 2022 COVID-19 pandemic and Russia-Ukraine conflict dragged the index to 0.374, while subjective factors such as the “14th Five-Year Plan” policy drove the 2023 index rebound to 0.415. Objective factors include global and local resource endowments, the macroeconomic environment, technological advancements, climate change, natural disasters, and emergencies. Subjective factors cover marine fisheries management, policy support, financial support, knowledge reserves and professional qualities of fishermen, and international cooperation. Here, we will select several key factors for detailed analysis and explanation.

4.1. Macroeconomic Environment

The marine fisheries economy is one of the traditional industries within China’s national economic system. Looking ahead, both global macroeconomic conditions and China’s domestic economic environment will exert varying degrees of influence on the development of China’s marine fisheries. At the global level, a favorable economic and trade environment is generally associated with stronger seafood demand. As incomes rise and consumption structures upgrade in some countries, demand for aquatic products may increase and become more diversified, which can generate spillover effects on seafood production, processing, and sales not only within exporting countries but also across interconnected regional markets.

From a domestic perspective, China’s macroeconomic environment is likely to play an even more pronounced role in shaping the development trajectory of marine fisheries. Sustained economic growth contributes to the stabilization of market expectations, the expansion of consumption demand, and the improvement of investment conditions, all of which are important for the steady operation of the fisheries sector. According to the International Monetary Fund’s projections for 2024, China is expected to become the largest contributor to global economic growth over the next five years, accounting for approximately 21.7%, exceeding the combined contribution of all G7 countries. China’s economic growth rate is projected to reach 5% in 2024 and 4.5% in 2025.

Economic recovery and sustained improvement provide a relatively stable external environment for the development of marine fisheries. A sound macroeconomic context can support the continuous expansion of domestic seafood consumption, enhance the resilience of fisheries-related enterprises, and reduce uncertainty faced by producers and market participants. At the same time, positive economic performance increases the government’s fiscal capacity, creating favorable conditions for fiscal expenditure, tax support, and investment in infrastructure and public services related to marine fisheries. These factors collectively contribute to improving market opportunities and development conditions for the marine fisheries sector, thereby exerting a supportive influence on its sustainable development potential.

4.2. Technological Progress

The development of various fields in marine fisheries, such as fishing vessel manufacturing, aquaculture models and fishing technology innovations, seedling cultivation, seafood processing and sales, all rely on the support of science and technology. The development, progress, and support of science and technology are key to enhancing the sustainable development level of marine fisheries. In 2023, China proposed a new concept related to science and technology, namely “new quality productive forces”. On 5 March 2024, “new quality productive forces” was written into the government work report for the first time. Currently, China’s fisheries management authorities and numerous scholars are exploring what the new quality productive forces of marine fisheries are and how to develop them. Coastal provinces and cities such as Shandong, Guangdong, Jiangsu, and Hainan are also actively exploring how science and technology can support the sustainable development of regional marine fisheries. Looking ahead, the speed of technological progress may exceed our expectations. The ability of science and technology to empower the transformation and sustainable development of China’s marine fisheries industry is expected to continue to strengthen, which is a strong positive factor for the sustainable development of marine fisheries. However, some technologies—especially artificial intelligence (AI) and disruptive technologies—may bring specific risks to marine fisheries (e.g., AI resource assessment models biased by incomplete small-scale fishing data could lead to overfishing; high-cost AI aquaculture equipment may widen the income gap among fishermen), requiring advance risk prediction and response.

4.3. Management and Policy Support

Management and policy serve as the compass for industrial development. The healthy and orderly development of marine fisheries is inseparable from scientific policy guidance and advanced management methods. Unsustainable practices, regulatory barriers, and improper incentive measures may hinder seafood production. Fisheries management can facilitate the recovery and reconstruction of overexploited populations. The future development of China’s marine fisheries will be influenced by international policies and actions, such as the FAO’s “Blue Transformation Roadmap,” “Sustainable Aquaculture Industry Guidelines,” and “Port State Measures Agreement,” among others. These provide directions for countries to achieve sustainable growth, promote equitable benefits, reverse environmental degradation, and combat IUU. China has also joined the “Port State Measures Agreement,” implementing strict supervision and cracking down on violations. By developing alternative aquaculture production (e.g., integrated multi-trophic aquaculture, deep-sea cage aquaculture), China is expected to achieve a shift from fish biomass decrease to biomass recovery. The “United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change,” the “Convention on Biological Diversity,” the BBNJ international agreement negotiations, and the ongoing global plastic convention will also have some impact on the development of marine fisheries. From China’s perspective, support for fisheries management and policy has been continuously increasing. Previously, a series of documents have been released, including the Fisheries Law of the People’s Republic of China, Implementation Plan for the ‘Five Major Actions’ for Promoting Green and Healthy Aquaculture Technology in 2024, Opinions on Accelerating the Development of Deep-Sea Aquaculture, Opinions on Promoting High-Quality Development of Deep-Sea Fisheries in the ‘14th Five-Year Plan’ Period, and National Fisheries Development Plan for the ‘14th Five-Year Plan’ Period. It is expected that around 2026, China will release the national fisheries development plan for the “15th Five-Year Plan” period, providing clearer guidance on the direction and focus of marine fisheries development. In addition, coastal areas often release development plans, guidance opinions, and management regulations for fisheries and sub-sectors in their regions. For example, at the end of 2024, Guangdong Province released China’s first comprehensive industrial development plan for marine fisheries, i.e., the Guangdong Province Modern Marine Ranch Development Master Plan (2024–2035), and the Shandong Provincial Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs issued the Shandong Provincial Leisure Fisheries Management Measures.

4.4. Strength of Financial Support

The main actors in marine fisheries include large and medium-sized fishing enterprises, small and micro enterprises, and individual operators. Although these entities differ significantly in scale, production modes, and market orientation, their development universally depends on continuous financial support, with the required funding scale and financing channels varying across actors. In this sense, finance can be regarded as the lifeblood of sustainable development in marine fisheries, as it underpins investment in production capacity, technological upgrading, infrastructure construction, and risk management.

In recent years, the sources of funding for the development of China’s marine fisheries have become increasingly diversified. These sources include central government agricultural industry development funds, commercial bank loans, corporate financing through initial public offerings, and various specialized industry funds. Among them, agricultural industry development funds provided by the central government play a particularly important role in supporting key areas of the sector. Such funds offer targeted financial support for projects including the renovation and upgrading of offshore fishing vessels and onboard facilities, the deployment of gravity-type deepwater net cages and truss-type large-scale aquaculture equipment, the construction of primary seafood processing and cold storage facilities, pilot programs for green and circular development in fisheries, and the development of national-level coastal fishing port economic zones.

Despite the diversification of financing channels, the financial characteristics of China’s marine fisheries remain distinctive. The sector is generally associated with relatively high operational risks, pronounced heterogeneity across subsectors, limited availability of effective collateral, and a strong dependence on policy guidance and public support. These features often constrain access to commercial finance, particularly for small-scale operators and emerging business models. As a result, the continuity and adequacy of financial support play a critical role in determining whether marine fisheries can successfully advance green transformation, improve production efficiency, and enhance long-term sustainability. Consequently, the ability of the sector to secure sufficient and stable financial resources will remain a key factor influencing the sustainable development of marine fisheries in the future.

4.5. Impact of Emergencies

Recent years have witnessed a growing frequency of emergency events, which have affected various industries worldwide to differing degrees, with some impacts proving to be long-lasting rather than merely short-term. Marine fisheries, as a sector highly dependent on natural conditions, labor availability, logistics systems, and market stability, are particularly vulnerable to such external shocks. Emergencies often disrupt multiple links along the fisheries value chain simultaneously, including production, processing, transportation, and consumption, thereby amplifying their overall influence on sustainable development.

The COVID-19 pandemic represents a prominent example of how emergencies can exert substantial negative effects on marine fisheries. The pandemic disrupted fishing operations, aquaculture management, processing activities, and international trade, leading to supply chain interruptions and reduced market demand. In some regions, prolonged restrictions resulted in the suspension or closure of fishery-related enterprises, while employment opportunities declined sharply, placing considerable pressure on fishermen’s livelihoods and enterprise survival. Although economic activities gradually recovered after the pandemic, its impacts on market confidence, labor structure, and industrial resilience have extended beyond the immediate crisis period.

In addition to public health emergencies, environmental incidents may also generate significant and persistent effects on marine fisheries. From August 2023 to November 2024, the Fukushima nuclear power plant in Japan discharged nuclear-contaminated wastewater ten times, with a cumulative discharge of approximately 78,300 tons. This event raised widespread concerns in China and other countries regarding the potential safety and quality of seafood products. Even in the absence of confirmed large-scale contamination, heightened public risk perception has influenced consumer behavior, with some consumers believing that seafood from global waters may be unsafe. Such perception-driven responses can suppress market demand, affect price formation, and increase reputational risks for marine fishery products.

Geopolitical and regional security crises further compound uncertainty in the development of marine fisheries. Events such as the Red Sea crisis, the Russia–Ukraine conflict, and the Israel–Palestine conflict may disrupt international shipping routes, increase transportation and insurance costs, and alter global trade patterns. These changes can indirectly affect seafood production, sales, and trade in China and worldwide by increasing operational costs and reducing market accessibility.

Overall, emergencies are characterized by high unpredictability, and their negative and positive impacts are often difficult to quantify and forecast in advance. While some emergencies may stimulate adaptive responses or structural adjustments within the industry, they more commonly introduce instability and risk. As such, emergencies constitute an important external factor influencing the sustainable development trajectory of marine fisheries, particularly by increasing uncertainty and vulnerability in the short to medium term.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Main Conclusions

Through the above research, the following conclusions are drawn: Firstly, China currently places a high emphasis on the sustainable development of marine fisheries, and the overall operation of the marine fisheries economy is stable and plays an important role in the global fishing and aquaculture sectors. Secondly, according to the index assessment results, the sustainable development level of China’s marine fisheries was the lowest in 2022, and it has shown a rising trend year by year from 2021 to 2030. The potential for sustainable development of China’s marine fisheries is enormous, especially in the field of marine aquaculture. Thirdly, from the perspective of influencing factors, there are many factors that affect sustainable development, but the role of technology may become increasingly important. Policy and management, continuous financial support, and improvements in fishing equipment and facilities are also important guarantees for the sustainable development of marine fisheries.

5.2. Policy Recommendations

The sustainable development of marine fisheries is a highly coupled and coordinated system involving multiple elements, such as humans, marine resources, ecological environment, technology, and management. It requires a systematic approach to addressing this issue. Based on the assessment results and analysis of influencing factors, the following recommendations are proposed for China to promote the sustainable development of marine fisheries and make more contributions to the development of the global fisheries economy:

Firstly, from an economic perspective, efforts should be made to continuously optimize the industrial structure of marine fisheries. Although China’s marine fisheries economy has made significant contributions in terms of industry and output value, there is still considerable room for optimization and development of the marine fisheries industrial structure. China is recommended to vigorously promote the green and healthy development of the mariculture industry in the coming years, stabilize offshore aquaculture, advance deep-sea aquaculture, and promote mature, advanced, and green sustainable aquaculture models; develop offshore and deep-sea fishing in a reasonable and orderly manner, continuously improve various fishing moratorium systems, accelerate the renovation and transformation of marine fishing vessels, develop resource-friendly fishing, reduce destructive fishing methods such as trawling, adhere to the implementation of independent fishing moratoriums and transfer supervision on the high seas, and crack down on illegal fishing; develop recreational fisheries, encourage all regions to create regional recreational fisheries brands based on their geographical advantages and traditional characteristics, build different types of recreational fisheries bases, provide guidance for fishermen to switch to other industries and employment, support the inheritance of marine fisheries culture, and promote the integrated development of marine fisheries with tourism, offshore wind power, and other industries.

Secondly, from a technological perspective, efforts should be made to enhance the technological and modernization level of marine fisheries. China’s fisheries industry has been making active innovations in areas such as resource protection and utilization, aquaculture industry innovation, transformation of aquaculture models, and improvement of informatization and intelligence levels. However, compared with the needs of sustainable industrial development, there is still a certain gap in China’s fisheries technological innovation capabilities. It is recommended that in the coming years, technological innovation should be taken as an important support for the sustainable development of marine fisheries, and the construction of a technological innovation support system should be strengthened. China should encourage basic research innovation in fisheries, increase efforts in breeding excellent seawater varieties and tackling practical technical problems, improve the output rate per unit of water body, resource utilization rate, and labor productivity; strengthen the research, development, and promotion of new technologies and equipment; and focus on breaking through key technologies, developing core equipment, strengthening technical services, accelerating the cultivation of new business forms, and forming new quality productive forces in fisheries.

Thirdly, from the perspective of resources and environment, as marine fisheries still fall under resource-dependent industries, and there are still issues such as extensive production models and unsustainable development models in the industry’s development, efforts shall be made to place equal emphasis on ecological protection and resource conservation in the future. China is recommended to reduce high-density, high-pollution, and resource-environmentally destructive production models in the coming years and develop resource-saving, integrated planting and breeding, three-dimensional ecological, and environmentally friendly production models to achieve harmony and unity between production and ecology [

11]. The fishing industry should also adhere to the goal orientation of “matching to the carrying capacity of resources and environment”, exerting efforts in both fishing intensity control and output control to promote the sustainable use of fishery resources [

11]. At the same time, marine ecological restoration and environmental governance can be further strengthened, and resource conservation activities such as enhancement and releasing can be carried out. The calculation, implementation, and evaluation of enhancement and releasing tasks should be normalized, and aquatic biological marker releasing and tracking survey monitoring should be carried out to strengthen the evaluation of releasing effects, promote the recovery of fishery resources, purify the fishery water environment, and protect aquatic biodiversity.

Fourthly, from the perspective of factor guarantee, institutional innovation, fishing governance according to law, financial support, and a professional workforce are all indispensable for sustainable development of the marine fisheries. The marine fisheries administration authorities should play an important role in factor guarantees, such as revising and formulating relevant policies, regulations, and strategic plans based on economic development trends and market supply and demand changes and strengthening special guidance and policy system guarantees for the development of marine fisheries. In December 2024, the draft revision of the Fisheries Law of China was submitted to the 13th meeting of the Standing Committee of the 14th National People’s Congress for deliberation, aiming to better coordinate the development of aquaculture, fishing, and the proliferation and protection of fishery resources; promote the quality improvement and efficiency enhancement of the fisheries industry; and promote green development. Roadshows are held to facilitate the docking between financial institutions such as banks, leasing, funds, insurance, and fishery-related enterprises. Through roadshows, marine fisheries enterprises can introduce their development situation and financing needs, communicate with financial institutions on enterprise development prospects, operating income, etc., encourage and support financial institutions to innovate financing support models, and provide more high-quality marine-related financial services. In addition, marine fisheries community-level enterprises can join forces with other institutions, such as colleges and universities, educational and training institutions, specialized fishery research institutions, law enforcement agencies, public welfare organizations, etc., to build a professional fishery talent team and enhance fishery-related knowledge and skills.